Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Tacet Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

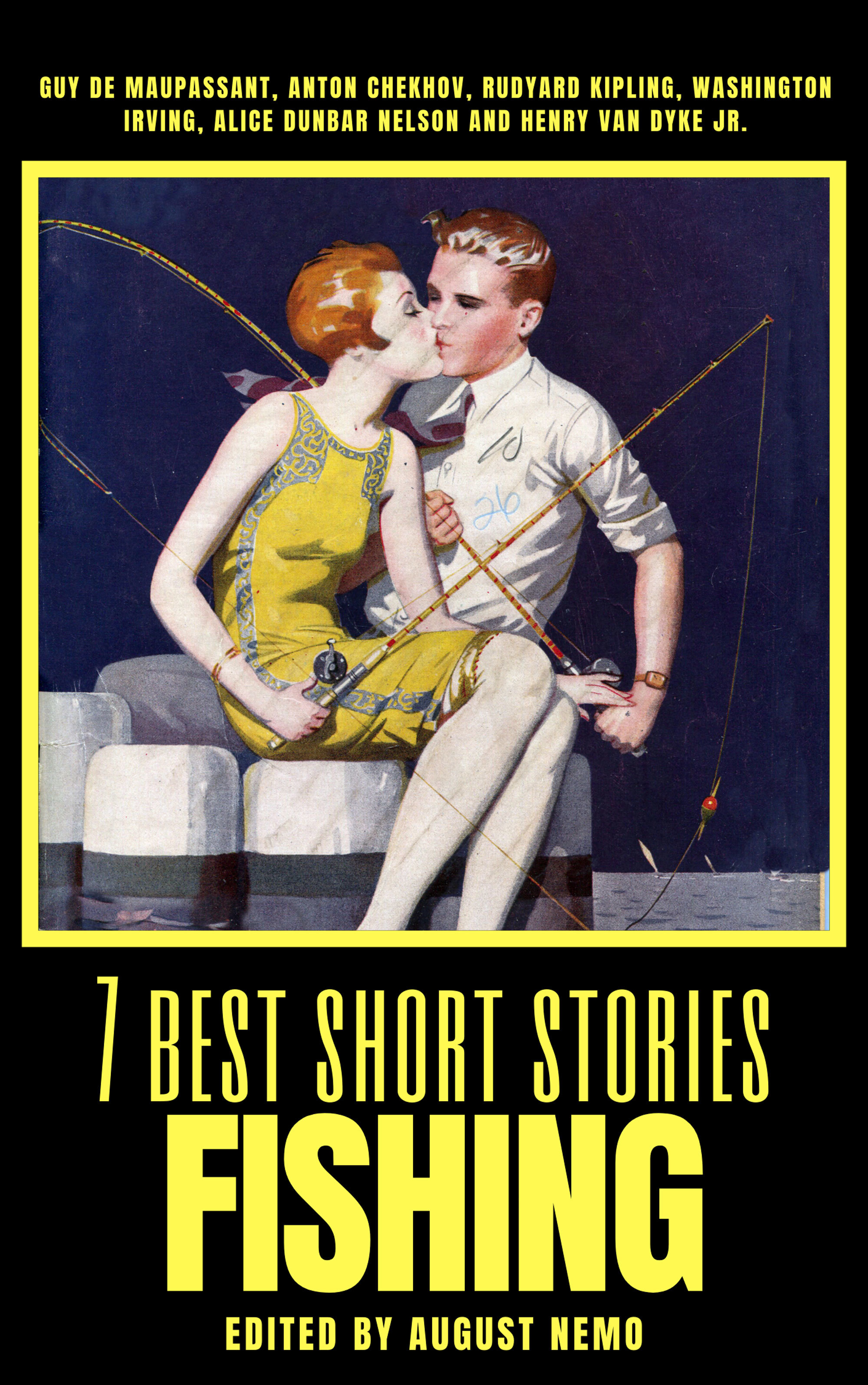

- Serie: 7 best short stories - specials

- Sprache: Englisch

One of humanity's oldest activities, fishing has a deep historical and cultural significance. Whether as a professional activity or as a holiday fun, fishing has been the subject of several pieces of literature. In this book, the critic August Nemo selected seven stories about fishing for your amusement. This book contains: - Two Friends by Guy de Maupassant. - A Daughter Of Albion by Anton Chekhov. - On Dry Cow Fishing as a Fine Art by Rudyard Kipling. - The Angler by Washington Irving. - Fisherman's Luck by Henry van Dyke. - The Fisherman of Pass Christian by Alice Dunbar-Nelson. - The Fish by Anton Chekhov.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 113

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Title Page

Authors

Two Friends

A Daughter Of Albion

On Dry Cow Fishing as a Fine Art

The Angler

Fisherman's Luck

The Fisherman of Pass Christian

The Fish

About the Publisher

Authors

Henri René Albert Guy de Maupassant was a 19th century French author, remembered as a master of the short story form, and as a representative of the Naturalist school, who depicted human lives and destinies and social forces in disillusioned and often pessimistic terms. Maupassant was a protégé of Gustave Flaubert and his stories are characterized by economy of style and efficient, effortless outcomes. Many are set during the Franco-Prussian War of the 1870s, describing the futility of war and the innocent civilians who, caught up in events beyond their control, are permanently changed by their experiences. He wrote some 300 short stories, six novels, three travel books, and one volume of verse.

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov was a Russian playwright and short-story writer, who is considered to be among the greatest writers of short fiction in history. His career as a playwright produced four classics, and his best short stories are held in high esteem by writers and critics. Along with Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg, Chekhov is often referred to as one of the three seminal figures in the birth of early modernism in the theatre. Chekhov practiced as a medical doctor throughout most of his literary career: "Medicine is my lawful wife", he once said, "and literature is my mistress."

Joseph Rudyard Kipling was an English journalist, short-story writer, poet, and novelist. He was born in India, which inspired much of his work. Kipling in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was among the United Kingdom's most popular writers Henry James said, "Kipling strikes me personally as the most complete man of genius, as distinct from fine intelligence, that I have ever known." In 1907, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, as the first English-language writer to receive the prize, and at 41, its youngest recipient to date. He was also sounded for the British Poet Laureateship and several times for a knighthood, but declined both.

Washington Irving was an American short story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He is best known for his short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" (1820), both of which appear in his collection The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. His historical works include biographies of Oliver Goldsmith, Islamic prophet Muhammad, and George Washington, as well as several histories of 15th century Spain that deal with subjects such as Alhambra, Christopher Columbus, and the Moors. Irving was one of the first American writers to earn acclaim in Europe, and he encouraged other American authors such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Herman Melville, and Edgar Allan Poe. He was also admired by some British writers, including Lord Byron, Thomas Campbell, Charles Dickens, Francis Jeffrey, and Walter Scott. He advocated for writing as a legitimate profession and argued for stronger laws to protect American writers from copyright infringement.

Henry Jackson van Dyke Jr. was an American author, educator, and clergyman. Among his popular writings are the two Christmas stories, "The Other Wise Man" (1896) and "The First Christmas Tree" (1897). Various religious themes of his work are also expressed in his poetry, hymns and the essays collected in Little Rivers (1895) and Fisherman's Luck (1899). He wrote the lyrics to the popular hymn, "Joyful, Joyful We Adore Thee" (1907), sung to the tune of Beethoven's "Ode to Joy". He compiled several short stories in The Blue Flower (1902), named after the key symbol of Romanticism introduced first by Novalis. He also contributed a chapter to the collaborative novel, The Whole Family (1908).

Alice Dunbar Nelson (July 19, 1875 – September 18, 1935) was an American poet, journalist, and political activist. Among the first generation born free in the South after the Civil War, she was one of the prominent African Americans involved in the artistic flourishing of the Harlem Renaissance. Her first husband was the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar; she then married physician Henry A. Callis; and married, lastly, to Robert J. Nelson, a poet and civil rights activist. She achieved prominence as a poet, author of short stories and dramas, newspaper columnist, and editor of two anthologies.

Two Friends

By Guy de Maupassant

––––––––

Besieged Paris was in the throes of famine. Even the sparrows on the roofs and the rats in the sewers were growing scarce. People were eating anything they could get.

As Monsieur Morissot, watchmaker by profession and idler for the nonce, was strolling along the boulevard one bright January morning, his hands in his trousers pockets and stomach empty, he suddenly came face to face with an acquaintance — Monsieur Sauvage, a fishing chum.

Before the war broke out Morissot had been in the habit, every Sunday morning, of setting forth with a bamboo rod in his hand and a tin box on his back. He took the Argenteuil train, got out at Colombes, and walked thence to the Ile Marante. The moment he arrived at this place of his dreams he began fishing, and fished till nightfall.

Every Sunday he met in this very spot Monsieur Sauvage, a stout, jolly, little man, a draper in the Rue Notre Dame de Lorette, and also an ardent fisherman. They often spent half the day side by side, rod in hand and feet dangling over the water, and a warm friendship had sprung up between the two.

Some days they did not speak; at other times they chatted; but they understood each other perfectly without the aid of words, having similar tastes and feelings.

In the spring, about ten o’clock in the morning, when the early sun caused a light mist to float on the water and gently warmed the backs of the two enthusiastic anglers, Morissot would occasionally remark to his neighbor:

“My, but it’s pleasant here.”

To which the other would reply:

“I can’t imagine anything better!”

And these few words sufficed to make them understand and appreciate each other.

In the autumn, toward the close of day, when the setting sun shed a blood-red glow over the western sky, and the reflection of the crimson clouds tinged the whole river with red, brought a glow to the faces of the two friends, and gilded the trees, whose leaves were already turning at the first chill touch of winter, Monsieur Sauvage would sometimes smile at Morissot, and say:

“What a glorious spectacle!”

And Morissot would answer, without taking his eyes from his float:

“This is much better than the boulevard, isn’t it?”

As soon as they recognized each other they shook hands cordially, affected at the thought of meeting under such changed circumstances.

Monsieur Sauvage, with a sigh, murmured:

“These are sad times!”

Morissot shook his head mournfully.

“And such weather! This is the first fine day of the year.”

The sky was, in fact, of a bright, cloudless blue.

They walked along, side by side, reflective and sad.

“And to think of the fishing!” said Morissot. “What good times we used to have!”

“When shall we be able to fish again?” asked Monsieur Sauvage.

They entered a small cafe and took an absinthe together, then resumed their walk along the pavement.

Morissot stopped suddenly.

“Shall we have another absinthe?” he said.

“If you like,” agreed Monsieur Sauvage.

And they entered another wine shop.

They were quite unsteady when they came out, owing to the effect of the alcohol on their empty stomachs. It was a fine, mild day, and a gentle breeze fanned their faces.

The fresh air completed the effect of the alcohol on Monsieur Sauvage. He stopped suddenly, saying:

“Suppose we go there?”

“Where?”

“Fishing.”

“But where?”

“Why, to the old place. The French outposts are close to Colombes. I know Colonel Dumoulin, and we shall easily get leave to pass.”

Morissot trembled with desire.

“Very well. I agree.”

And they separated, to fetch their rods and lines.

An hour later they were walking side by side on the highroad. Presently they reached the villa occupied by the colonel. He smiled at their request, and granted it. They resumed their walk, furnished with a password.

Soon they left the outposts behind them, made their way through deserted Colombes, and found themselves on the outskirts of the small vineyards which border the Seine. It was about eleven o’clock.

Before them lay the village of Argenteuil, apparently lifeless. The heights of Orgement and Sannois dominated the landscape. The great plain, extending as far as Nanterre, was empty, quite empty-a waste of dun-colored soil and bare cherry trees.

Monsieur Sauvage, pointing to the heights, murmured:

“The Prussians are up yonder!”

And the sight of the deserted country filled the two friends with vague misgivings.

The Prussians! They had never seen them as yet, but they had felt their presence in the neighborhood of Paris for months past — ruining France, pillaging, massacring, starving them. And a kind of superstitious terror mingled with the hatred they already felt toward this unknown, victorious nation.

“Suppose we were to meet any of them?” said Morissot.

“We’d offer them some fish,” replied Monsieur Sauvage, with that Parisian light-heartedness which nothing can wholly quench.

Still, they hesitated to show themselves in the open country, overawed by the utter silence which reigned around them.

At last Monsieur Sauvage said boldly:

“Come, we’ll make a start; only let us be careful!”

And they made their way through one of the vineyards, bent double, creeping along beneath the cover afforded by the vines, with eye and ear alert.

A strip of bare ground remained to be crossed before they could gain the river bank. They ran across this, and, as soon as they were at the water’s edge, concealed themselves among the dry reeds.

Morissot placed his ear to the ground, to ascertain, if possible, whether footsteps were coming their way. He heard nothing. They seemed to be utterly alone.

Their confidence was restored, and they began to fish.

Before them the deserted Ile Marante hid them from the farther shore. The little restaurant was closed, and looked as if it had been deserted for years.

Monsieur Sauvage caught the first gudgeon, Monsieur Morissot the second, and almost every moment one or other raised his line with a little, glittering, silvery fish wriggling at the end; they were having excellent sport.

They slipped their catch gently into a close-meshed bag lying at their feet; they were filled with joy — the joy of once more indulging in a pastime of which they had long been deprived.

The sun poured its rays on their backs; they no longer heard anything or thought of anything. They ignored the rest of the world; they were fishing.

But suddenly a rumbling sound, which seemed to come from the bowels of the earth, shook the ground beneath them: the cannon were resuming their thunder.

Morissot turned his head and could see toward the left, beyond the banks of the river, the formidable outline of Mont-Valerien, from whose summit arose a white puff of smoke.

The next instant a second puff followed the first, and in a few moments a fresh detonation made the earth tremble.

Others followed, and minute by minute the mountain gave forth its deadly breath and a white puff of smoke, which rose slowly into the peaceful heaven and floated above the summit of the cliff.

Monsieur Sauvage shrugged his shoulders.

“They are at it again!” he said.

Morissot, who was anxiously watching his float bobbing up and down, was suddenly seized with the angry impatience of a peaceful man toward the madmen who were firing thus, and remarked indignantly:

“What fools they are to kill one another like that!”

“They’re worse than animals,” replied Monsieur Sauvage.

And Morissot, who had just caught a bleak, declared:

“And to think that it will be just the same so long as there are governments!”

“The Republic would not have declared war,” interposed Monsieur Sauvage.

Morissot interrupted him:

“Under a king we have foreign wars; under a republic we have civil war.”

And the two began placidly discussing political problems with the sound common sense of peaceful, matter-of-fact citizens — agreeing on one point: that they would never be free. And Mont-Valerien thundered ceaselessly, demolishing the houses of the French with its cannon balls, grinding lives of men to powder, destroying many a dream, many a cherished hope, many a prospective happiness; ruthlessly causing endless woe and suffering in the hearts of wives, of daughters, of mothers, in other lands.

“Such is life!” declared Monsieur Sauvage.

“Say, rather, such is death!” replied Morissot, laughing.

But they suddenly trembled with alarm at the sound of footsteps behind them, and, turning round, they perceived close at hand four tall, bearded men, dressed after the manner of livery servants and wearing flat caps on their heads. They were covering the two anglers with their rifles.

The rods slipped from their owners’ grasp and floated away down the river.

In the space of a few seconds they were seized, bound, thrown into a boat, and taken across to the Ile Marante.

And behind the house they had thought deserted were about a score of German soldiers.

A shaggy-looking giant, who was bestriding a chair and smoking a long clay pipe, addressed them in excellent French with the words:

“Well, gentlemen, have you had good luck with your fishing?”

Then a soldier deposited at the officer’s feet the bag full of fish, which he had taken care to bring away. The Prussian smiled.

“Not bad, I see. But we have something else to talk about. Listen to me, and don’t be alarmed:

Tausende von E-Books und Hörbücher

Ihre Zahl wächst ständig und Sie haben eine Fixpreisgarantie.

Sie haben über uns geschrieben: