9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

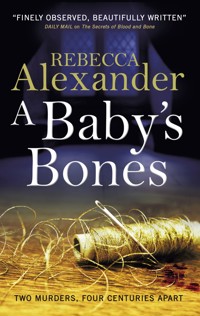

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

"Finely observed, beautifully written" Daily Mail on The Secrets of Life and DeathArchaeologist Sage Westfield has been called in to excavate a sixteenth-century well, and expects to find little more than soil and the odd piece of pottery. But the disturbing discovery of the bones of a woman and newborn baby make it clear that she has stumbled onto an historical crime scene, one that is interwoven with an unsettling local legend of witchcraft and unrequited love. Yet there is more to the case than a four-hundred-year-old mystery. The owners of a nearby cottage are convinced that it is haunted, and the local vicar is being plagued with abusive phone calls. Then a tragic death makes it all too clear that a modern murderer is at work…

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also Available from Rebecca Alexander and Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

“Alexander turns her hand to the historical whodunnit with a strong central image; an ancient well with a dark secret at the bottom and a modern tragedy waiting to happen at the top. Her love of the past, its myths and misdeeds, shines through every page.” CHRISTOPHER FOWLER

“A deliciously chilling murder mystery which gathers such terrific pace and suspense that it was impossible to break free of its dark and malevolent spell. Enthralling and immensely satisfying.” KAREN MAITLAND

“I can only admire the skill with which Alexander interweaves dark events of the past with events in the present. A compelling read.” MAUREEN JENNINGS

“A fascinating story connecting two mysteries centuries apart—a well-realized and haunting story with a vivid sense of time and place.” L.F. ROBERTSON

“A thoroughly enjoyable read – gripping, atmospheric and emotionally satisfying.” RUTH DOWNIE

“An expertly crafted dual mystery with a creeping sense of foreboding.” JOANNA SCHAFFHAUSEN

“An engaging and intricate mystery, steeped in dark drama and rich historical detail” M.L. RIO

Also available from Rebecca Alexander and Titan Books

A Shroud of Leaves (April 2019)

TITAN BOOKS

A Baby’s Bones

Print edition ISBN: 9781785656217

E-book edition ISBN: 9781785656224

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: May 2018

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiousl y, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 2018 by Rebecca Alexander. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book?

We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at

[email protected] or write to us at

Reader Feedback at the above address.

TITAN BOOKS.COM

For my parents,

JILLIAN ALEXANDER

who taught me to read and love books, and

JOHN ALEXANDER

who told me stories of history that

still fascinate me today.

1

Monday 25th March

It was a bone from a baby’s arm. Like a twig on Sage Westfield’s glove, the ends crumbled away by the action of the sieve, it was still distinctive to a trained eye.

‘I’ll get a second opinion as to date,’ she said, pushing a handful of dark curls out of her eyes with the other hand. ‘I’m certain the bones are contemporary with the spoil filling the well. Sixteenth century, Tudor.’

The police officer pointed at another small heap of finds. ‘You’re sure they aren’t animal bones, then? Cat, maybe?’

‘These are human.’ The afternoon breeze blew across the garden, shivering the evergreen hedges that crowded Bramble Cottage. ‘I think we have at least one adult and a baby, probably newborn or up to a couple of months old. We’ll need an expert to be sure. It’s surprising they’ve survived this long.’

‘And you found them yesterday?’

‘Actually, one of my PhD students found the first one. Elliott Robinson.’ Sage pointed to the finds table where Elliott was crouched on the ground examining the spoil pile, watched by Steph, her undergraduate student. Elliott didn’t look up, but Steph waved. ‘I just labelled the bones as they brought them out.’

The policeman made a note of the find numbers on the containers. ‘I’ll let the Home Office know it’s historical.’ He looked at her swollen belly on her otherwise slim frame. ‘Sad, really, a baby. Have you seen many like this?’

‘I’ve never seen anything like it.’ Sage placed the bone on a pad of bubble wrap. ‘It’s really unusual to have a burial outside consecrated ground. But to put two bodies down a well, and cover them with the contents of a midden – that’s very rare.’ Her phone beeped but she ignored it.

‘Midden?’

‘Medieval rubbish dump. We’re finding broken pottery, cooked bones, probably mixed with manure. That’s what’s so disrespectful about it. It does suggest the need for a quick or secret burial. Maybe even murder.’

The police officer paused at the word, looking down at the handful of dark brown fragments. ‘Care to hazard a cause of death?’

Sage smiled at him, shaking her head, then glanced at the house. The windows reflected the yellowed, late afternoon clouds. Her smile faded. ‘The owners aren’t going to like this.’

He followed her gaze up to tiny dormers embedded in the thatch. ‘The house must have cost a packet. They’re new to the Isle of Wight, aren’t they?’

‘Yes. They needed listed building consent and an archaeological survey before they could start an extension. Then we found the well, and they had to foot the excavation bill. Now we have bodies—’ Her phone beeped again. She glanced at it. Marcus. Lunch?

The officer put his notebook away. ‘We’ll get back to you. But for now, please treat the site as limited. Any remains to be recorded, held together, and secured for further examination. At least until we confirm it is historical.’

‘Of course.’ Sage watched him walk around the side of the cottage, on the tarpaulins she had laid down to save the lawn. Little chance of that, now the dig had to be extended. She wrote a message back to Marcus. Busy. She really didn’t have time for his drama today.

She looked at the blank eyes of the cottage. They stared over the hedge and across fields that ran west, up the slight hill to the ornate chimneys of the manor house beyond. Banstock village sat on a promontory with the sea on three sides, and she’d loved to come here as a child. She had never been to the manor house; perhaps she was too young to appreciate it before they moved off the Island. She glanced up back at the stone walls of the cottage. Under its thick coat of thatch it should have been picturesque, but the place gave her the creeps. The yawn of the well drew in the darkness that had gathered under the hedge, and she pulled her coat around herself. She could only hope the baby had been dead when it was thrown into the water. She touched her bump. Her emotions were definitely getting the better of her nowadays.

* * *

‘Hello?’ Sage called in the front door, left slightly ajar despite the cold weather. ‘Mrs Bassett?’

The owner of the cottage padded into the flagstone hall. She seemed insubstantial in a sweater that hung from bony shoulders. ‘Come through to the lounge.’ Even her voice was thin.

Sage considered her splattered boots, sat on the step to unlace them and went into the hall in her socks. The staircase beside her was blackened oak, smoothed to a pale brown on the treads, curved by five hundred years of feet. A child’s coats hung on brass pegs, the bright colours incongruous against the reproduction coffer and pine hall table. A wicker dog basket under the stairs held a tartan blanket, clean and folded.

She followed Mrs Bassett into the plainly furnished living room, where an unlit woodburner sat in the inglenook fireplace. The beam over the opening was blackened by hundreds of years of open fires. Sage ran her hand over the timber, feeling tool marks along its length. Her host looked through the French doors to the havoc wreaked on her garden.

‘So, it is actually a well,’ the faded woman said. She turned to look at Sage with an assessing expression. In the half-light she appeared older than the thirties she probably was, shadows gathering in the hollows of her face and her eye sockets. ‘I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to stare.’

‘It’s OK. My mother’s from Kazakhstan. No one believes I was born on the Island.’ Wide cheekbones and almond-shaped eyes had always given Sage’s Turkic heritage away.

Mrs Bassett sighed. ‘Is the well recent or old?’

‘We think it’s an original Tudor well, very rare and brilliantly preserved. It’s been filled in with material from a rubbish pit, that’s why we’re getting so many bits of old pots and glass. Wonderful finds.’ Sage let her enthusiasm colour her voice. She knew, if she could get the site’s owner motivated, the knotty problem of funding the dig would become easier. ‘But there’s more to it than just the pottery. We’ll have to dig deeper.’

‘What you’re saying is, it will cost more money. Tea?’

‘Yes, please. Milk, no sugar. Mrs Bassett—’

‘Judith.’ The woman twisted a smile, which quickly sagged. ‘You’ll need to be here longer, I suppose. Come through to the kitchen.’

Like the living room, the kitchen was bland: white walls; a cream Aga that wasn’t lit; and plain oak cupboards. A draught blew in from the door to the hall. Judith filled an electric kettle, the water splashing into the silence.

Sage decided that there was no good time to break the news. ‘I’m afraid there is a problem with the well itself.’

Judith’s shoulders tensed but her voice was level. ‘What kind of problem?’

‘When we sifted some of the spoil from the excavation, we found bones. Some of them appear to be human.’

The woman froze, a teabag suspended between finger and thumb, for several seconds. Then, as if the music had started again, she dropped the bag into the mug. ‘Human?’

‘It appears that at some point, probably centuries ago, someone buried two people in the well. There appears to be at least one adult and a baby. I asked the police along to document the finds but they are happy it’s historical.’

Judith placed a mug decorated with bright cartoon robins onto the granite work surface in front of Sage, then surveyed her over the rim of her own cup. ‘Is this going to be a big problem?’

‘We’ll be in contact with the Home Office,’ Sage said. ‘Then we can definitively establish that these are historical remains. I’m afraid we’ll have to excavate the rest of the well, to ensure we have recovered all of the bones.’ She softened her tone, but Judith appeared unmoved. When she spoke, her voice was harsh.

‘My husband’s in the hospice. They say there’s little chance of survival. I can see he’s dying. Eight months ago we were a normal family, looking forward to moving to the Island, changing schools. He’s only forty-three.’

That explained the woman’s remoteness. She looked overwhelmed.

‘I’m so sorry. I didn’t know.’ Sage wrapped her cold hands around her mug. ‘This must be dreadful for you.’ She shivered as a draught brushed her neck, and she found it hard not to flinch.

‘I hate this house,’ Judith said. She looked out of the front window, to the drive and the road beyond. The whole property was bordered by a yew hedge, gnarled and twisted with age. ‘I hated it from the day we moved in. It’s cold, it’s dark. Maybe it’s haunted.’

‘I’m sorry?’

‘The house. Everything started to go wrong when we moved here.’ Judith sat on a kitchen stool. ‘It’s like what happened to the dog.’

‘I noticed the basket—’

‘He ran out into the road the day we got here. He was killed by a delivery van. We didn’t tell Chloe, she thinks he ran off. I couldn’t tell her the truth.’ Judith’s voice wobbled, and she swallowed hard. ‘It was also the week James was diagnosed. I had to tell her Daddy had cancer. She’s only nine.’

‘I wish I didn’t have to add to your burden at such a bad time,’ Sage said. No wonder Judith thought the house felt haunted. ‘Do you think you’ll try and move?’

‘James is too ill. He’s the one who wanted a conservatory in the first place.’

‘I’m sorry,’ Sage said. ‘We’ll try to get the work done as fast as we can.’

Judith turned, and the smile on her face was distorted into a grimace. ‘I don’t care what you do outside. We aren’t going to bother with the extension now, anyway. Do your excavation, write your reports. Will it cost us a lot more?’

‘More than we originally anticipated, I’m afraid. Your planning application fee covers the basic excavation uncovering the well. Your home insurance may help, and some costs may be borne by the Home Office as we’ve found human remains.’

‘Human remains,’ Judith said. ‘How long will it take, with just the three of you?’

Sage drained the last of her tea. ‘We’ll work as fast as we can. In the meantime, I have to ask you not to go near the excavation – it isn’t safe. I’ll board it up before I go. I do hope you get some good news about your husband soon.’

‘Me too.’ Judith switched the hall light on as she escorted Sage to the front door. In the yellow glow she seemed younger, but ill and exhausted. ‘Maybe when the bones go, our bad luck will stop.’

Sage looked around. The cottage did seem like the archetypal haunted house: dark passages; lots of odd corners; creaking timbers; and bone-scouring draughts. She shivered as the wind from the open door found its way down her collar.

‘There’s an evil presence here,’ Judith said. ‘I can feel it.’

Sage stepped into her boots, and stood up, laces trailing. ‘I don’t really believe in ghosts, Mrs Bassett.’

Judith leaned forward. ‘Neither did I.’

2

29th June 1580

Two yards of fine linen for a baby’s shroud, for Lady Banstock two shillings and four pence Wages for Mistress Agness Waldren, who nurses the sick of red pox at Banstock four shillings Quarter’s wages for Mistress Isabeau Duchamp, for embroideries to your lordship’s daughter Elizabeth’s bride clothes, of three loose gowns and two kirtles eleven shillings and nine pence

Accounts of Banstock Manor, 1576–1582

It is a pious woman that sews her baby’s shroud while it still kicks within her. Baron Anthonie Banstock tups his second wife each spring and she brings forth a stillborn lamb each autumn. He has more hope this time; the last one mewed like a kitten for a day before it succumbed. Five babes lie in the vault, each in its hand-sewn winding sheet, at the will of a merciful God.

It seems to me that Elizabeth shall never wear her bride clothes, as she raves in delirium within her chamber. Already Lord Banstock has come to me to hint at a new betrothal to the younger sister, if the elder perishes. I am concerned. Fourteen years makes a poor bed-mate for nine-and-twenty, and the man Solomon Seabourne has a reputation for being a radical, perhaps even a papist. He waits at Ryde and his manservant, Edward Kelley, rides over each day for news of Elizabeth. The man Kelley is young and as sharp around the manor as a fox, asking this and that of the men, and the maids.

Mistress Agness, the rector’s sister, adds spinster’s vinegar to her tongue as she scolds our Viola: her hair should be bound and covered; her skirts are too short; she laughs immodestly.

When she was born, the travail took away Viola’s mother, Lady Marion. The baron might have cast the seven-month babe aside, but instead he ordered the whole castle to rally unto her. I first saw her by the kitchen fire, at the breast of a wet nurse. She was tiny, a red face in loose swaddling, for she was deemed too weak to risk tight wrapping. She stopped her suckling, and beheld me, as I leaned in curiosity over this daughter of the manor. We stared at each other, and I swear she knew me. They say babies are as blind as kittens, but wherefore are their eyes open? She gazed at me, then lowered her gaze to the milky nipple and fed as heartily as a lamb upon the ewe.

From that day, I found times to observe the child, and she grew accustomed to me. The baron carried her around the manor, so devoted was he, that we often sat over the accounts while she babbled on his lap or mine. As she grew older, she was confined to her nursery more, but still found hours to visit me in my office and play with my seals and keys. As she grew older she learned letters and numerals in my office, and traced her first words in ink on scraps of vellum from the rent rolls. Now fourteen, she is the darling of the castle, except for sour Mistress Agness.

It is she who chides Viola for visiting me, and none was more argumentative in the matter of Seabourne’s betrothal to Elizabeth. But a betrothal does not a marriage make.

Vincent Garland, Steward to Lord Banstock, His Memoir

3

Tuesday 26th March

‘Good morning.’ It was a deep voice, and it made Sage jump back and slip on the muddy edge of the excavation. She barely regained her balance. The morning had already been full of problems, and now she had a streak of clay down the inside seam of her jeans.

‘Shit. You startled me—’ Her words faded as she took in a dog collar on a tall man, late thirties maybe, with dark hair and round glasses. ‘Oh. You must be the vicar. Sorry, you surprised me.’

He smiled at her, which made him look younger. ‘Dr Westfield?’

‘Sage. County archaeologist.’ She stretched out a hand, before realising there was mud on her fingers.

He took it anyway, with the smallest of grimaces. ‘Nick Haydon. I’m the vicar of St Mark’s, Banstock church.’ His skin was warm, his grip firm.

Sage wiped her hand on her jeans, which made him smile wider. ‘Are you here to see the Bassetts?’

The smile faded. ‘Mrs Bassett doesn’t want me to visit. Actually, I’m here because the diocese has just been told about the bones. It’s likely any human remains will be interred up at the churchyard, once your investigation is complete.’ He looked towards the two students working under the flapping awning. Steph was working with a flotation tray, and Elliott was picking through the sievings from the day before.

Sage walked over to the folding tables. ‘Would you like to see what we have? Be careful, it’s slippery. Can we see what you’re working on, Elliott?’

The vicar followed her over to the tarpaulin, and Elliott carefully opened one of the bone boxes. ‘Don’t touch,’ the student warned. ‘They’re fragile. I’m cleaning them so they can go with the others.’ Leg bones from an adult: a tibia snapped like a twig; a kneecap; and about a dozen foot bones all laid out on bubble wrap. Elliott closed the box, and Sage moved to the table where she had started to lay out the cleaned bones. She removed the covering tarpaulin.

‘This is more of the adult’s remains.’ She found her voice naturally dropped. ‘The body seems to have been bent up, at least one leg forced above the head, fracturing the femur and lower leg bones. We’ve just uncovered the top of the head and a hand as well.’

‘The broken bones – did that mean he suffered some violence?’ The vicar’s face was animated by some feeling she couldn’t read.

‘Maybe. And we don’t actually know whether the bones are male or female. It wasn’t necessarily a violent death; the fractures may have been post-mortem. We’ll know more when we finish excavating the skull and pelvis.’ She picked up the sandwich box that sat next to the bone box and opened it gently. ‘These are bones from the baby we found with the adult.’

The bones were tiny, a handful of ribs, vertebrae and a few long bones.

‘No skull?’

‘We haven’t found it yet. The baby seems to have been buried upside down.’

The vicar looked back at her. ‘Would you mind if I said a prayer over these remains?’

‘Of course not.’

Sage stepped away, watching as he lowered his face and closed his eyes. He had long eyelashes the same black as his hair, and he seemed genuinely grieved for the people dumped in the well with the rubbish. Elliott stared at Sage; she wondered if he was offended by the ritual. He didn’t say anything, but Steph lowered her head.

After a quiet ‘amen’, echoed by Steph, Elliott carefully covered the bones. Sage glanced up at the house, remembering the overshadowed woman from yesterday.

The vicar walked over. ‘Thank you. When will you be able to release the bones for reburial?’

‘First we have to prove definitively that they are more than a hundred years old. Then we have to make sure we have as many as have survived – it’s likely a lot of the baby’s bones have just dissolved away. I’m surprised we have so many. We also need to make sure there aren’t any more bodies down there.’

‘Why would someone bury a body in a well?’ His voice was strained.

Sage shrugged. ‘It’s too early to tell. Wells are valuable resources, they are expensive to dig out and line. We occasionally see burials in wells in disease events like plague. It was an easy way to dispose of remains. Other reasons include war or even murder. Sometimes bodies were used to foul the water and make the well unusable. But the pottery we are finding is too late for that. There were no wars being fought on the Isle of Wight at the time.’

‘Horrible.’

She nodded towards the boxes of bones. ‘I can’t imagine why they would deny these people a Christian burial.’ She felt awkward talking to a vicar about faith, especially since she didn’t have any. ‘I mean, almost everyone was a believer at the time.’

‘Maybe it was murder, then.’

‘Perhaps.’ Sage wrapped her arms around herself against the wind. Even with the sun out, it was going straight through her fleece.

‘Will you be here for the whole excavation?’ He nodded at her bump. ‘I mean, you seem to have your own deadline.’

‘I’m not due until June. I’ll let you know as soon as we finish with the bones. It will be some time, months rather than weeks.’

‘Thank you.’ He leaned towards her and lowered his voice. ‘The Bassetts. Do you know anything about them?’

‘I know her husband’s very ill. And Mrs Bassett, Judith, she—’ Sage couldn’t find the words to describe the wraith that she had spoken to the day before. ‘She seems frozen, you know?’

‘In what way?’

Sage zipped up the fleece over her bump and pulled up her collar. ‘She didn’t react. I mean, we find the body of a baby in her garden, and she’s worried about how much the recovery will cost. Obviously, her husband’s illness is more important. Then she said the house is haunted.’

The vicar smiled grimly. ‘Maybe it is. There are at least two bodies down the well. Ghosts are supposed to be associated with violent deaths or being denied Christian burial.’

‘You have to be kidding. You can’t believe in ghosts.’

‘I don’t “believe” in ghosts, it’s not a faith thing.’

Sage folded her arms. ‘I just thought vicars wouldn’t be great fans of the supernatural.’

He smiled, apparently with genuine amusement. ‘On the contrary. We’re all about the supernatural.’ He reached into a pocket and pulled out a dog-eared card. ‘Here’s my number, if you need to get in touch about the burial. The woman who used to own Bramble Cottage, Maeve Rowland, she knows all about the house’s history. She might be worth a visit. She always said the place was haunted too.’

Sage took the card and stuffed it into a pocket. ‘Haunted? By what?’

His forehead wrinkled. ‘I was never sure whether it was just a voice or she actually saw something. You should ask her. She moved into a local residential home, the Poplars, but she lived here for several decades.’

‘Thanks, I’ll do that if we have time. The Poplars.’

‘It’s set back from the road at the top of the high street. She would love a visitor.’ The vicar smiled again, which changed his whole face, she thought, from long and serious to warm and friendly. ‘She’s had a stroke but is still sharp as a pin. Anyway, I’ve got visits to do. I expect I’ll see you again.’

‘We’ll be retrieving evidence for a few weeks. Possibly longer,’ Sage said.

‘Maybe we can discuss the procedures involved in burying these poor lost bones. I’ve never done anything like this before.’ He stared up at the sky, as a few spatters hit his jacket. ‘It’s really starting to rain.’

‘The forecast did say heavy showers.’ Sage scrabbled in her pocket for one of her own business cards. ‘Call me if you need more information. Oh, and, vicar—’

‘Nick, please.’ That smile again, curving up the corners of his mouth.

‘I’ll be speaking with Mrs Bassett. If I can help in any way, let me know.’

He thought for a long moment. ‘If the opportunity arises, tell her that the support we offer is pastoral and practical, as well as spiritual comfort. Lifts, babysitting, someone to talk to. That sort of assistance. I promise not to overwhelm her with beliefs she doesn’t share. But I’m pretty handy with a lawnmower, and we have volunteers who do the school run.’

‘I’ll tell her if I can.’ Sage could feel her smile pulling at her cold cheeks. She watched as he walked away, and felt a little warmed, especially when he turned at the corner of the house and smiled back at her.

* * *

The late morning brought heavier rain, whipped around the garden of Bramble Cottage by a wind that slapped the awning against the poles that supported it. Sage kept most of the delicate finds locked in the van.

The adult’s skull slowly emerged, crown first, like it was being slowly born from a womb of clay. The face was strong; she was unsure at first whether it was male or female. Elliott and Steph, invigorated by the jawless face overlooking the dig, redoubled their efforts to find more vertebrae, more ribs, more of the baby’s crumbling bones including half a tiny pelvis by lunchtime.

Sage suggested they decamp to the village pub, the Harbour Bell, for a chance to warm up and dry off. Even in a padded jacket, Steph’s teeth were chattering. She treated Elliott to a soft drink, bought Steph a shandy, and ordered herself a large decaffeinated coffee while they waited for their food.

The dig seemed to have made Elliott even more taciturn than usual, but Steph got up to look around the panelled walls and beckoned Sage over enthusiastically. ‘Have you seen these pictures?’

Sage looked around the pub, which was perhaps as old as the cottage. The walls were decorated with old farming implements, harness for heavy horses, and leather buckets were sat on shelves. Between them were a series of sepia photographs.

‘Are they Friths?’ she asked. A Victorian photographer named Francis Frith had recorded thousands of scenes across Britain in the 1800s.

Steph leaned in to examine one more closely, standing on tiptoes. ‘No – these look like they were taken by an amateur.’ She turned to the woman at the bar. ‘These are great,’ she said. ‘Are they pictures of houses in the village?’

The landlady nodded. ‘They are. Some old rector of St Mark’s took loads. His widow left them to a previous landlord.’ She nodded at Sage and Elliott. ‘Are you the people digging up Bramble Cottage?’

Steph smiled, flicking long blonde hair out of her eyes. ‘We’re looking into the history of the place. Are there any photographs of the cottage?’ Sage was impressed by her people skills, as Steph waved at the pictures. ‘I see there’s a lovely one of the pub.’

The landlady lifted up the hinged end of the bar, and took down a framed print near the door. She placed it carefully on the table in front of them, and dusted it off with a tea towel tucked into her waistband. ‘That’s Bramble Cottage, I think.’

The cottage looked different, the thatch thin and the chimney leaning at a perilous angle. A woman in an apron and holding a baby stood beside the house, at the side where the main door was now. She stared ahead with the serious rigidity of the Edwardian subject, but the baby was a blur of movement.

‘Oh, God, it could even be them,’ Steph breathed. Then she shook her head and grinned. ‘Of course not, I’m being stupid. No photography in the sixteenth century.’

‘It’s most likely the bodies are contemporary with the fill,’ Sage pointed out. ‘You’re also jumping to the conclusion that the baby in the well is buried with its mother.’

The landlady stepped back. ‘A baby?’

Sage winced. The last thing she wanted was speculation while they had so few facts. ‘We haven’t finished our investigations yet. But we have found a few bones. It would be better if we didn’t broadcast it until we have all the facts, though.’ That cat was probably well out of the bag; gossip ran around the Island like electricity. It was one of the things she disliked about coming back here to live. The Isle of Wight had less than two thirds the population of neighbouring Southampton on the mainland, spread over a hundred and fifty square miles, but it had a village mentality.

The woman’s eyes were wide. ‘Oh my God, there have been rumours about that old cottage for years. It’s supposed to be haunted, you know.’

Sage smiled up at her. ‘Old houses are always thought to be haunted. I’ve seen a lot of old houses in my job but I’ve never seen a ghost.’

Elliott drained his drink, put his long forearms on the table, and frowned. ‘I wonder if we could look at the back of the photograph? There might be some useful information.’

Sage turned it over, but it was sealed with paper tape.

The landlady shook her head. ‘I don’t know if Den would want us messing about with it.’

‘Den?’

‘That’s the old landlord, Dennis Lacey; he’s my husband’s father. He lives with us since we moved in to help run the Harbour Bell. He’s very protective of all the old stuff.’ She pursed her lips, as Elliott brought out a hand lens to study the picture. ‘I’ll ask the old bugger, but he’s grumpy today.’

As she left, the food arrived from the kitchen: toasted sandwiches and a bowl of chips to share. Sage, Elliott and Steph were halfway through their meal when the landlady returned, this time with an elderly man leaning on her arm. His slight frame produced a surprisingly hearty voice. ‘You them history folk, Carol tells me.’

Sage stood up, and offered her hand. ‘Dr Sage Westfield, sir. These are archaeology students from South Solent University, Elliott Robinson and Stephanie Beatson. We were admiring your collection of local pictures.’

‘Don’t you “sir” me, young lady. Den’ll do.’ He glanced at the picture on the table. ‘You want to know about that old cottage, do you? What’s your interest, then?’

‘It’s a listed building. I’ve been asked to check there aren’t any archaeological features before allowing the building of an extension.’

Den grunted something and settled in the seat beside Elliott. ‘You should have talked to me first. I could have told you to watch your step over there. That house is haunted, shadowed with evil my gran used to say. She should know, she lived in the village all her life.’

Steph’s eyes were round. ‘Is there really a ghost?’

Sage couldn’t help rolling her eyes but Den laughed, a crackle of sound that started him coughing. When he got his breath back, he explained. ‘Ghosts ain’t no trouble, girl, at my age you sees them all the time. No, there’s a nasty atmosphere over there. Bad luck.’ He paused. ‘You know about the grave in the woods?’

Sage looked at the students. Steph stared back at her, Elliott shrugged. ‘We haven’t heard anything about it,’ she said.

‘When I was a boy, Bramble Cottage’s garden extended right to the boundary of the manor. Now it’s partly common land, because the Banstocks donated some of it to the village, and they sold the rest off for housing.’ He stretched in his chair, folded his arms. ‘The old grave was past the stream. We used to think it was haunted, a burial like that. We thought old Damozel – that’s what’s written on the stone you see – must be a witch, buried so far from the church. The headstone might even still be there.’

Sage could see the conversation getting derailed as Elliott opened his mouth to ask more questions. She beat him to it. ‘We were wondering whether we could take a look at the back of this photograph,’ she said, holding it up. ‘We’re just looking for more history on the cottage.’

He stared at it for a long moment. ‘No problem. Cut it off.’

‘Thank you. I’ll be careful.’

Sage turned the picture over in her hands and brought her mobile kit out of her pocket. She removed a small scalpel, gently slit the modern framing tape, and lifted out the card backboard. The reverse of the photograph had something written on it in pencil. ‘I can’t read it – have either of you got a light?’

Both students offered pencil torches. Illuminated, the elaborate letters became clearer.

Well House.

* * *

The afternoon brought relief from the rain for the archaeologists, but their work was interrupted by a small girl rushing around the side of Bramble Cottage. She careered towards the excavation and Sage had to grab her before she hit the flimsy barrier.

‘Whoa! Careful, it’s deep.’

‘Can I see?’ The child was pretty, blonde hair restrained in plaits. She stared at the mess they had made of the ground. ‘You made our garden really muddy.’ She strained to see down the well, already a hole seven or eight feet deep.

Sage smiled at her, but subtly waved at Elliott to cover the human remains. ‘We’re learning about the history of your house. Of course you can come and have a look while we’re here, but I want you to promise you won’t come into the back garden on your own. It’s not safe. OK? Promise?’

The child peered into the hole. ‘I promise. That’s really deep. I can see it from my bedroom.’ She scrutinised Sage. ‘You’re really pretty. Are you Chinese?’

‘My mum’s from a country a long way away, called Kazakhstan.’ She glanced at Elliott, who put up a thumb. ‘So, what’s your name?’

‘Chloe Eloise Bassett. What’s yours?’

Sage introduced herself and the students, and showed the child the stones at the top of the well. Chloe soon lost interest and Sage handed her over to Steph, who got some of the pottery shards out, and started talking about Tudor history.

Judith Bassett walked around the side of the house, trudging over the mud in unlaced shoes. ‘Chloe! Stop bothering these people, they’re working.’ Her face was pale, her lips pressed together.

‘It’s OK, Mrs Bassett,’ soothed Steph. ‘We were just looking at some pots.’

‘Steph says I can borrow some things to take into school to show them.’ The child held out a fragment of earthenware. ‘Look, this is a bit of a jug. It’s really old, like Henry the Eighth.’

‘Just artefacts from the well,’ Sage added. ‘Nothing upsetting.’

Judith was shaking, her arms wrapped around herself. ‘I don’t want Chloe involved with the well. I don’t want her upset in any way.’ She reached out and grabbed her daughter, snatching the pottery out of her hand and throwing it to the ground. Before anyone could respond, she swung the child up into her arms, walking quickly back towards the house. Chloe stared over her mother’s shoulder, holding Sage’s gaze until she was carried out of view. Her fingers dug into her mother’s neck, leaving little red welts.

Elliott scooped up the pot shard. ‘Are you OK?’

Sage nodded, watching the door close, hearing a lock turned. ‘Just a bit surprised.’ She rummaged in her pocket and found her spare set of keys. She dropped them into his hand. ‘Can you two put the bones in my van? I want to be prepared in case she orders us off the property.’ Then she took out a pen and one of the find record cards. She jotted down an apology and her mobile phone number and dropped it through the letterbox of Bramble Cottage.

4

5th July 1580

Stones to be cut for the new well, two masons and a master, at five pence each day and ten pence for the master mason eighteen shillings and eight pence to date

Accounts of Banstock Manor, 1576–1582

The masons have started lining the new well. The old one, being at the back of the house, is only convenient for the use of one property, and brackish at best. Banstock stands on a promontory surrounded by the sea: it creeps into the soil and shallow wells. This one is but thirty years old and is already useless for drinking, built as it was from bits of stone from the abbey. Some say it was cursed by the abbot as he was chased from his own church, beaten and left for dead in his herb garden.

The new well will be for the use of all the houses in the village of Banstock. It will be at the side of the road. The water man advises it is fed from a natural spring. The mason, Master Clintock, having much knowledge of wells but no longer able to go down the ladder, supervises the men as they set the stones into the shaft. Already the base, a great slab of limestone cut for the purpose, is covered with two feet of water, which makes the mortaring difficult. Boys heave up buckets filled by the masons each morning, and tip them into the pond in front of the church, with a choir of lamentation from the resident ducks and geese. Only then can the work resume.

As the steward of the Banstock estate I shall be asked to account for the bill for this second well, and already the masons are disputing the figure. I have told them I shall pay no more than five pence a day hire to each man but I know I would pay six for fast work, and they would manage with four. They are working fast to race the water, and so far are winning, but each night gives the spring the advantage, so I have authorised the use of extra lamps to extend the day through the whole length of the well. It is nearly two rods deep and we tasted the water before the mortaring began and found it sweet.

Viola, the youngest daughter of Lord Banstock, is with me. Her father and I deem it better that she be out of the house as her sister lies mortally affected by the red pox. Viola teaches a group of children to write their numbers in the road with a long pole. The hem of her dress is dusty, her hands are yellow with clay from helping to dig and she looks nothing like the daughter of a baron. Yet I admit I do not wish to stop her, for the long days of childhood are passing faster than she imagines, in her fifteenth year.

Five years ago the succession was assured, with two adult sons and a clutch of married daughters. Now bad fortune and illness have left us with just one male heir, and him on a perilous journey with Drake. At the manor my Lady Flora’s women are a-twitter at her belly, and Lord Banstock, yet again, prays for a healthy son.

Vincent Garland, Steward to Lord Banstock, His Memoir

5

Wednesday 27th March

There was no sign of Judith Bassett or her car when Sage arrived at the cottage to set up the following morning. As Elliott was setting up the tables under the awning – Steph was at the university, attending classes – a car pulled onto the gravel drive behind her van. A young man in torn jeans and a graffiti-covered jacket jumped out.

Elliott strode over to meet him. ‘Can I help you?’ His tone didn’t sound very helpful.

‘It’s OK, Ell, I’ll deal with this.’ Sage watched him walk back to the table, still scowling. The man fished in the pocket of his leather jacket.

‘Hi. Dr Westfield, right?’ He flashed her an ID card. ‘Paul Turpin, structural engineer. I’m here to have a look at the well.’

She shook his hand. ‘Sage. It’s over here.’

Turpin stopped just short of the edge, and scanned the hole. ‘Bloody hell. It’s way too close to the house. If it collapses, it could take the foundations and back wall out.’ He touched the top of the ladder. ‘Tell me you haven’t been down there.’

‘OK,’ Sage lied, ‘I haven’t been down there.’

‘You can’t just climb down into a well that old. It’s likely to collapse on you.’

Sage smiled at him. ‘It seems in such good condition.’

‘Of course it’s in good condition, it’s been filled in. But if you take out the stabilising fill, you have a circular five-hundred-year-old garden wall.’ He leaned over, looking down into the void. ‘You’ve gone down, what, three metres?’

‘Almost. The thing is, two metres down – easy reach with tools – we found a human bone.’

Turpin looked up at her, his fringe flopping over a row of studs in one eyebrow. If she hadn’t seen his credentials, Sage would have taken him to be an art student.

‘Wow.’ He knelt on the tarpaulin surrounding the well, and peeled it back from the edge. ‘That’s good masonry,’ he said. ‘I mean, for a five-hundred-year-old death trap. Well mortared, dressed to fit tightly.’

‘So it’s safe.’

‘Ha.’ He started scraping away at the top stone. ‘No. Have you seen this?’

Sage bent to look. The top ring of stones was flat, but Turpin’s scratching had revealed what appeared to be intentional tool marks.

‘I thought the well would have a little wall around it for safety, and might have been levelled at some point,’ she said.

‘Some wells are like that, mostly to prevent injury, but flat wells are also fairly common. This one probably would have had a capstone or wooden cover, with a hole big enough to take a bucket, but it would stop people and animals falling in.’ Turpin stood, and put one foot onto the top of the ladder they had been using to bring up buckets of spoil.

‘I thought you said it wasn’t safe?’

‘Not for you, but I’m a professional.’ He carefully climbed a few steps down the ladder, and started scraping the algae and mud away from the walls. ‘I think this was always meant to be a shallow well.’

‘How do you know?’ Sage could see his hands moving over the stones, in the light of the rigged lamp.

‘The stones are mortared very solidly at the top, well fitted together. Down here,’ his voice echoed in the tight space, ‘the mortar isn’t complete. I don’t think it was designed to be. The water table’s high in this area of the Isle of Wight, over Pleistocene clays on top of marls and limestones. The looser fit of the stones allowed water to trickle in.’ He was momentarily illuminated by a flash from his phone. ‘The water must have picked up salt at high tide. There are a lot of crystals down here.’

Sage waited until Turpin had climbed out before she spoke. ‘We need to get the infill out to completely remove the skeletons and hopefully, establish the history of the interment.’

‘Of course.’ He leaned forward and showed her the image on his phone. ‘Look at this.’

One of the blocks had a carving in it. The algae had clung to the inscription after he had scraped at the surface. The shapes were crudely scratched but complex, curves and squiggles that looked intentional. It reminded her of ancient Greek, but she couldn’t quite place it. ‘What is it?’

‘Absolutely no idea. It looks like there are other inscriptions down there. Creepy.’

‘Why creepy?’ She leaned over the edge.

‘Well, someone had to go down the well to carve them. That’s good limestone, so it would have taken some time. They would have had to do it by candle or lamp light, and the well would have had to be empty.’

Sage studied the carved shapes, brushing more mud off the stones. Curves would have been much harder to carve than straight lines; someone had gone to a lot of trouble to put them in a circle around the well. ‘I’ve never heard of a well being decorated like that. Maybe it’s for luck, or some sort of religious blessing.’ Sage called Elliott over to show him the picture. ‘Or possibly the stones were carved before they were used for the well,’ she speculated. Then her memory threw up an image. ‘I think there might be something similar on a beam inside the cottage. Over the fireplace.’

Elliott stepped forward. ‘Can we get a copy of that photo?’

‘Sure.’

‘Good idea. Could you send it to my work email, please?’ Sage considered the engineer’s words. ‘You said “good limestone”. What did you mean?’

‘Definitely not quarried on the Island.’

She reached for her project bag, and unfolded the laminated 1866 map of the area. ‘The old abbey, here, was broken up after the dissolution of the monasteries.’ She tapped the map. ‘Apparently, the site’s completely cleared now, but a lot of the local buildings have some of the blocks. I wondered if some of the stone for the cottage came from the abbey.’

‘That could be it.’

‘So maybe it was already carved, like I said.’

‘I doubt it, this isn’t fine work.’ Turpin shrugged. ‘Empty it out and have a look. There’s a contractor, Rob Greenway. He’s a caver, and he also digs and drills wells. Give him a ring. He can dig out that lot quicker, and probably more safely, than you can. But no more exploring. Just put out a tarp next to the well and Rob will bring the fill up for you.’ He pulled a colourful scarf from a pocket, and wound it around his neck. ‘It’s cold, isn’t it?’

Sage knelt down to examine more of the symbols. ‘These carvings don’t look ecclesiastical, they’re just deep scratches. They look like folk symbols, superstitious shapes for good luck. They would be well worth another look.’

Elliott bent over the image on Turpin’s phone. ‘I’ll look them up, see if I can find anything similar on a database.’

‘We’ve got dead bodies, weird carvings and ghosts,’ Sage said. ‘I’m a scientist. I just want to work out what happened here. People are already telling me the house is haunted.’

Turpin smiled. ‘Dead bodies, spooky carvings, old houses. Of course it’s haunted. Or it will be, if you go down the well and it collapses on you.’

* * *

An hour after Paul Turpin left the excavation, Sage was surprised to see Judith Bassett carrying out a tray of tea and biscuits. She handed it to Sage. ‘I’m sorry about yesterday. I just saw the well, and Chloe – I didn’t want to make her sad or frightened. The idea of those poor people down there, it upset me.’

Sage smiled, put the tray down on a worktable. ‘We understand. It must be incredibly unsettling to find bodies in your garden, especially with the other stresses you are under.’

Elliott stuffed his phone into his pocket and took a mug, nodded his thanks, then turned back to cleaning pottery.

‘He doesn’t say much, does he?’ Judith said quietly, handing Sage the second mug.

‘He’s very focused. He’s doing a PhD, and takes it very seriously.’ Sage could see Elliott turn to Steph. She immediately came over, wiggling her fingers in her nitrile gloves.

‘Ooh. Tea.’ Steph wrapped her hands around the mug. ‘Thank you, my hands were freezing in that water. I’m washing off pottery,’ she explained. ‘Some of it’s late Tudor, which is quite unusual for this part of the Island. Normally we’d get this quality of finds at big sites like manors and churches.’

‘Have you found anything new?’ Judith looked across at the tables where trays were laid out with finds. ‘No more bodies, hopefully.’

Sage answered. ‘Well, nothing we’ve found suggests a third person. It looks like one baby and one adult, probably female. The skull is neither classically male nor female, but the bits of pelvis we found suggest the remains of an adult female.’

‘So a mother and baby?’

‘Maybe. We’ll be able to tell more when we have the rest of the pelvis.’ Sage sipped her tea. ‘The sixteenth century was a time of high infant mortality, deadly diseases. Maybe the well was useless; the surveyor said it was very salty. So in an emergency, people might have used a disused well to dispose of bodies, although it seems unlikely.’

Steph chimed in. ‘People cared deeply about burial practices, they still do.’

Judith shuddered in the fresh breeze. At least weak sunshine was breaking through the clouds. ‘It’s very sad.’ She wrapped her scarf more tightly around her neck.

‘But a long time ago,’ said Sage. ‘Steph, where’s that jug piece you found?’

Steph showed Judith the handle of a jug she was cleaning up. ‘Some of these pots were imported from Europe. Good quality. The owners of the cottage were prosperous.’

Judith smiled faintly, but didn’t look interested. She followed Sage over to the awning as a few spots of rain fell, and nodded at Sage’s stomach. ‘This can’t be an easy job for you, being pregnant.’