9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

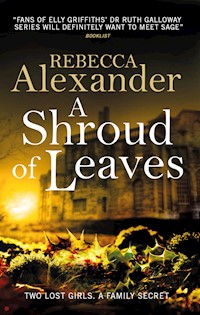

"Finely observed, beautifully written" Daily Mail on The Secrets of Life and Death"The victim had been buried in a carved hollow in the grass and shrouded in fallen leaves…"Archaeologist Sage Westfield has her first forensics case: investigating the murder of a teenage girl. Hidden by holly leaves, the girl's body has been discovered on the grounds of a stately home, where another teenage girl went missing twenty years ago – but her body was never found. The police suspect the reclusive owner, Alistair Chorleigh, who was questioned but never charged. But when Sage investigates a nearby burial mound – and uncovers rumours of an ancient curse – she discovers the story of another mysterious disappearance over a hundred years ago. Sage will need both her modern forensics skills and her archaeological knowledge to unearth the devastating truth.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Praise for A Baby’s Bones

Also available from Rebecca Alexander and Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

Praise forA Baby’s Bones

“An intricately plotted mystery…bittersweet and haunting.” LIBRARY JOURNAL

“Steeped in dark drama and rich historical detail.”

M.L. RIO

“An engrossing read that perfectly blends the historical and contemporary for a brilliant story.”

THE CRIME REVIEW

“Enthralling and immensely satisfying.”

KAREN MAITLAND

“One of my favourite reads of the year.”

CRIMINAL ELEMENT

“A compelling read.” MAUREEN JENNINGS

“Gripping, atmospheric and emotionally satisfying.”

RUTH DOWNIE

Also available from Rebecca Alexander and Titan Books

A Baby’s Bones

TITANBOOKS

A Shroud of Leaves

Print edition ISBN: 9781785656248

E-book edition ISBN: 9781785656255

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: July 2019

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 2019 by Rebecca Alexander. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

TITANBOOKS.COM

For

LILY ALISON BAVE

who made me a grandmother.

1

Monday 18th March, this year

Chorleigh House, Fairfield, New Forest

The victim had been buried in a carved hollow in the grass and shrouded in fallen leaves. Dr Sage Westfield accidentally brushed one slate-blue hand, which the pathologist had uncovered. Even through gloves, she could feel the cold, waxy flesh, unlike anything she had experienced before at an excavation.

‘Sorry,’ she breathed, as much to the corpse as the pathologist.

Dr Megan Levy grimaced back. She was a sandy-haired woman who looked like she was in her forties. ‘I’m guessing this is your first burial scene?’

‘The first one less than a hundred years old, yes. I’ve done a lot of classes and observed a couple of recent post-mortems, but I wasn’t expecting to be called to a recent murder.’ The grave reminded Sage of an Egyptian sarcophagus, rounded at the head end and tapered to the feet. The forensic suit rustled when she moved; she was wearing a hood and overshoes as well. The investigation team looked like ghosts drifting in the late afternoon gloom; pools of artificial light from lamps sharpened the silhouettes of the people huddled around the grave.

She checked her field bag again. Camera, extra batteries, notebook, tablet, phone, charger for the car. Evidence bags in different sizes, trowels, labels, marker pens, brushes, hand lenses. Most of her classes were about the law and rules of handling and preserving evidence; she didn’t feel at all prepared for an actual burial that wasn’t hundreds or even thousands of years old. It was all about local, recent stratigraphy of soil layers; how someone had dug the grave and covered it up. Her supervisor, Trent, was probably just there so the police could prove they had covered all the bases. She glanced up to see an older man, stocky, staring back at her. He gestured with a curled finger and she stood up.

‘Dr Westfield?’ She nodded. ‘The archaeologist from the island, I presume. Where’s Trent?’

‘I’m one of his students. Well, I’ve known him for more than a decade – we trained together.’

He looked over his shoulder. ‘Stay out of the woods!’ he barked at someone working beyond the scrubby lawn, towards the trees that encroached on the space in front of the house. ‘And lay some more forensic pads.’ He turned back to Sage. ‘I need the real thing, not a student. I want to know how that grave was dug, what it means.’

Sage swallowed the first three things she wanted to say. ‘I phrased that badly. I am a fully qualified, experienced scientist. Until last year I was the county archaeologist for the Isle of Wight, and I lecture at the university with Trent. I’m completing additional training in forensic techniques.’

He stared at her a bit longer, until she felt uncomfortable. ‘I’m the SIO, DCI Lenham.’

SIO, DCI. Senior Investigating Officer, Detective Chief Inspector Lenham.

She looked him in the eye. ‘Trent is supervising me. He’s working on the road verge; he’s found some anomalous tyre impressions.’ All around was the New Forest, a national park on the south coast just a few miles from Sage’s home on the Isle of Wight. The property was a large one, an imposing Victorian house in a garden with woodland all around. Originally, the rank grass would have been part of about an acre of lawn, possibly surrounded with flower beds. Now straggly shrubs were intertwined with brambles and spindly trees.

‘OK, then. Yesterday we had a missing girl and at fifteen years old, the most likely scenario was that she had run away.’ He turned to look at the house. ‘Now we have a body, found by a local woman walking her dog. Megan, let me know as soon as you find something. First impressions, anything. Trent thinks there might be footprints into the trees; I’m keeping everyone else out.’

Sage knelt down on the plastic sheet beside the grave, avoiding Dr Levy. ‘Charming,’ she muttered to the pathologist. ‘What do you need me to do first?’

‘Don’t mind Graham. He’s a good man, really experienced, just a bit impatient. This might be quite an easy investigation. They’ll interview the owner of the garden first – he’s top of their list as a suspect, then family and friends. That normally identifies the main suspects. What I need you to do is catalogue all the materials covering the body, systematically, so the prosecutors can build the case.’

Sage sat back on her heels. The corpse was covered in thousands of leaves, mainly, it seemed, holly and ivy, which looked deliberately placed. ‘We can’t number each one.’

Megan raised a sandy eyebrow. ‘We sometimes have to, but honestly, I think some are falling apart and there are too many. No, you photograph stacks in situ, lift, bag and catalogue. The person who buried her had to do that; they couldn’t have carried the whole lot. That way if we find anything anomalous we can say where it was in relation to the remains.’ She smiled at Sage, the white light gleaming on a crooked tooth. ‘We’ll chill the leaves down to preserve evidence. Then you and the forensic team can examine them in the lab for fibres, fluids, even fingerprints if the glossier leaves will hold one.’

Sage took out her camera, checked the battery and focused on the leaves at the head end of the grave. ‘OK.’ After a few flashes and some more taken under the light from the lamps, she was able to lift a small stack of wet leaves, pressed together and smelling musty. She wrote the picture numbers and location on the bag as she’d been taught. She stood up to take a larger picture of the whole site and added a grid to the image.

Megan asked to see. ‘Nice idea. We use laser scans but they are always moving. I have to make measurements on the ground. Send me a copy and I’ll use the same grid for my observations too.’

Sage started snapping a handful of leaves near the body, the flash picking up the first threads of blonde hair underneath.

Megan was crawling over the plastic sheeting on the other side, peering at the exposed hand. There was glittery nail varnish, a little flaky and growing out, and three parallel scratches. ‘I think we can say it’s probably a female from the small hands and the polish,’ the pathologist said. ‘We can’t be certain yet, but Lenham suspects this is River Sloane, the missing teenager from Southampton. I wonder how she ended up here, in the forest.’

Sage swallowed and looked away. The fingers were swollen; they didn’t look real. Her experience as a county archaeologist was mostly about bones and artefacts. This was too real, someone that she could have seen on the street a few days ago had actually died. ‘What happens when I’ve got all the leaves off the top?’

‘We’ll remove the body, then you and Trent will start working on the grave cut itself.’

Sage looked around. ‘It’s not obvious where they put the spoil. There should be some pieces of hacked-off turf somewhere around. It’s very neat, deliberate.’

‘We’ll have to identify anything they moved,’ Megan said. ‘Log all your observations as you go. I use a voice recorder but your phone will do. Send in the file along with your finished notes. We want everything.’

The remains had been nested in a blanket of leaves, laid in a cut roughly the shape of the body. It widened at shoulders and hips. Sage lifted a few more leaves, revealing the purpled chin, and tried to avoid touching it. The colour made the areas of exposed skin look stretched by gases building up, and Sage knew that the faint smell heralded a cascade of decomposition processes. She glanced at the face revealed as she lifted the next batch: definitely female, young, the milky eyes staring up at the sky, beginning to bulge. Textbooks and research on forensic archaeology hadn’t prepared Sage for the sadness, the horror of it. Even mortuary visits had been distant, factual. This was intense. She bagged more leaves, trying not to touch the body, and wrote on the label.

Megan leaned forward to zoom in on something. She sat back and breathed out, making her mask billow. ‘OK, Sage. What can you tell me from our initial survey?’

‘She’s covered with leaves. I suppose that’s odd, not to cover her with the soil they dug out.’

‘Which means?’

Sage thought. ‘I’m not sure – maybe they wanted her to be found quickly?’

‘Maybe. With all this work they could have buried her deeper in the same amount of time. And something else.’ She eased a few large leaves off the neck. ‘Look at these leaves. They weren’t shovelled on, they were placed very carefully.’

‘Overlapping, almost tenderly?’ said Sage.

‘That’s possible,’ Megan said. ‘Although in some murders it would mean the killer wanted to revisit the body. The “ick” range of tenderness. We worry more about a sexual motive if the body is undressed.’

Sage looked around the slight mound of leaves. ‘Oh.’ She lifted more piles of leaves, took photographs, bagged them and recorded their location. Slowly, the body emerged, naked so far. On the right side of the face were dark smudges. The regular pattern caught Sage’s eye and she leaned in. ‘What is that?’ Trying not to touch the skin, she pointed at a few dark spots in a line. ‘Bruising?’

‘You’ve got a good eye,’ Megan said, snapping a few close-ups. ‘I don’t know what caused it. It could be something she was hit with, or fell onto. It’s diffuse and looks ante-mortem. Sometimes marks on the skin develop further in the morgue. I’ll look into it at the post-mortem examination and we’ll swab it for trace.’ She smiled up at Sage. ‘Well done.’

Sage bagged another stack of leaves and sat back to write up the label. The grave was beyond the house, away from the road. Sage could see a glazed door in the outbuilding that might have looked over the garden originally, but several of the panes were missing and filled in with cardboard. The looming house had a dozen windows along the front, the painted sashes were peeling and there was cracked glass on the top floor. Someone had carried the body past the front door with its stone steps, past the dark frontage and the outbuilding, and buried it without being seen.

As Megan adjusted the light Sage could see purplishred stippling on the opposite side from the bruising. Sage understood the post-death processes from recent reading but the reality was making her shiver inside. For a moment, she remembered finding her dead student the year before and her heart pounded in her ears. The pathologist flexed the girl’s fingers, moved her jaw. ‘Rigor mortis isn’t completely gone. In these temperatures, I wouldn’t expect to see that before thirty-six to forty-eight hours, but with a wide margin of error. Her temperature is less than six degrees, a little warmer than ambient because soil retains heat. Can you see the post-mortem staining there?’

‘Livor mortis.’ Sage had to swallow hard again as she caught another whiff of something from the body. Maybe it was just the mouldering leaves. The girl looked as if she was emerging from the forest floor like some sort of tree spirit. ‘Hypostasis,’ she managed, looking down at the plastic sheeting, trying to get her emotions back under control. ‘Where the blood has pooled and stained the skin.’

‘Exactly. Here it’s on the left side of her face.’ The pathologist gently lifted a few more layers of covering and shone her torch underneath.

‘She does appear to be naked,’ Sage said, concentrating on keeping her voice steady as she lifted another pile of leaves. ‘Does that mean a sexual motive?’

‘Possibly but it might also be a forensic countermeasure. Even criminals know about transferred trace evidence and DNA now. Look here, on the left side of the torso. Why is there no post-mortem staining on her shoulder?’

‘Pressure stopped the blood concentrating there,’ Sage said through rising panic from flashbacks of a face in the black water of a well. ‘Maybe she was lying on a hard surface on her side? The blood would have collected in the lowest tissues, except where the blood vessels were compressed.’ She counted the flashbacks away.

‘Deep breaths,’ Megan said, staring so intently at the body that for a moment Sage thought she was talking to the dead girl. ‘Deep breaths will help you avoid the dizziness. We tend to hold our breath because of the smell and dizziness can make the nausea worse.’ She glanced up. ‘Pathologist’s trick. You were looking a bit blue.’

Sage took a few breaths, closed her eyes and accepted the definite sweet-vile hint in the air. It smelled like rotten meat somehow sprinkled with cheap perfume. ‘It’s just cadaverine and putrescine,’ she murmured, half to herself. ‘Just chemicals, normal breakdown.’

Megan half laughed. ‘Honestly, this is nothing. Try and focus on the smaller tasks and the bigger picture fades.’

The details burned into Sage’s brain, like the plastic bags Megan was taping onto the hands, like the insect scurrying along the girl’s lips to hide away in her mouth. Sage swallowed and looked up. She saw Trent, her supervisor, approaching.

‘So, what do we do after we have collected all the leaves?’ she asked him as he knelt beside her on the plastic sheet.

‘Well, as you know, our job is to tell people what we need them to leave as part of the primary forensic survey. The initial briefing divides the evidence into what each specialism will concentrate on.’

Sage thought back to her classes. ‘So, the pathologist gets the body, obviously, and records the position and relationship to the grave site. Forensics will look for any transfer, footprints, fibres and fingerprints. We do the grave and surrounding areas.’

‘The layers of covering materials like the leaves need to be documented and preserved,’ he said, nodding. ‘You’ve made a good start. We’ll make a site plan of the scene and advise what samples need to be taken. Someone dug the hole; we need to be able to say how and what with. What they covered her with will say something about what they were thinking. Archaeology will tell the investigation what was there. The police and other investigators will read that evidence, suggest why it was done. Sometimes we use a forensic anthropologist too.’

‘OK.’ Sage struggled with the taste of bile in her throat. ‘Sorry. The smell is getting to me a bit; I’m used to historical sites where we only date to a century or so. Do you have an anthropologist involved?’

Trent half smiled in sympathy. ‘No, so we’re doing both jobs here.’ He lowered his voice. ‘If you feel sick, there’s a bucket in the car. If you can’t make it, throw up in an evidence bag. We can’t contaminate the scene.’ He bagged a few more leaves. ‘I still feel rough, occasionally. Kids are harder. We probably won’t need an anthropologist, there’s a lot of crossover between us and them. We do know about burial rituals, so we can look for evidence of religious or cultural traditions as well.’

‘OK.’ Sage swallowed, hard. ‘I’m OK.’ She looked across the mound of leaves and twigs. ‘There’s evidence of some digging in the surface area around the site. We should photograph that. And take samples, in case they covered her up with soil from somewhere else. I can’t see any trees that these leaves might have come from.’

The pathologist took a few more pictures, the flash whitening the skin.

The sound of a keening, animal cry reached Sage. She jumped and looked around. ‘What’s that?’ The garden was waist high with bracken and brambles in places. The sky was darkening, the clouds gathering a purple tinge as the March daylight faded. Technicians were pulling the tent over the grave, putting more lights in place.

Sage stood awkwardly, making sure her booties didn’t touch the grave edge, and followed Trent away from the burial. A few gulps of air got her nausea under control. The wailing had turned to wrenching sobs, coming from a huddle of people beyond police tape that was keeping press and locals at bay. A woman was supported by a bearded older man, a teenage girl beside them. The girl turned her head to stare at Sage, her expression blank. The woman screamed again, then subsided into hoarse sobs. The man was crying, the lights catching the tears on his face.

‘Family,’ said Trent, his lips tight. ‘This is the hard bit.’ He snapped a few pictures of the grass around him.

‘How did they even know? I mean it might not be their daughter.’

‘The radio and TV reported that a body had been found and a road sealed off three hours ago. The family recorded an appeal with the press last night.’ Trent frowned. ‘The psychologists will be looking at that, frame by frame.’

‘I suppose they have to assume the family knows something.’

Trent grimaced. ‘Do you know what percentage of child murders are done by parents? We have to be careful not to give away anything we find out. Everyone’s a suspect at this point. Obviously, the owner of the house. Also, teachers, friends, neighbours – but mostly parents or their partners. You better get back before the press get a picture.’ He moved away, taking more pictures of the crime scene as he went.

A scuffle behind her made Sage look towards the house. Two police officers were wrestling a tall, heavy-set man from the front door to the road. He fought them, falling onto his knees until they almost carried him along, sweating and struggling. DCI Lenham helped drag him towards the police vehicles.

‘Mr Chorleigh, this isn’t helping. Let us get your statement, then you can come home,’ Lenham said as the big man shook him off.

A small dog barked around them until one officer nudged it hard with his foot and it yelped.

‘The little bugger bit me,’ he said, and Chorleigh swore and fought the officers until they snapped handcuffs on his wrists.

Sage moved forward and crouched down and called to the dog. ‘Here, puppy. Over here, there’s a good boy.’ It froze, watching her, then trotted over. She caught it by its collar. ‘Who deals with the dog?’ she asked, but Lenham was pulling the man to his feet.

‘RSPCA or kennels,’ he said, out of breath. ‘If we can’t find a relative or neighbour.’

‘I haven’t done anything wrong!’ the man howled, fighting them. ‘And it’s not his fault.’ He was dressed in several layers of old jumpers with a shabby coat over the top. It was hard to guess his age; he looked old and ill but could have been as young as mid-forties.

A young policewoman held out a tattered lead and Sage clipped it on. There was something about the man’s fear for his dog that touched her. ‘I’ll make sure he’s looked after. Is it a he?’ It was difficult to tell under matted hair.

Watching her, Chorleigh seemed to calm down a little. ‘Hamish. He’s only two, he’s a bit boisterous. He’s allergic to fish.’

‘I’ll tell them.’ The man passed quite close to Sage as he was hauled to the police vehicles. In the distance someone shrieked, a man bellowed – perhaps they had caught sight of the suspect. Sage picked the dog up. It was a white terrier, with long greasy fur. It strained to reach its owner, to lick his face. ‘He’ll be fine.’

‘I didn’t do anything,’ he started to say as he was dragged into the van. ‘I haven’t hurt anyone.’

‘You said that last time,’ Lenham muttered under his breath. He lifted his hand to touch the dog, then pulled it away. ‘He’s filthy. You’ll need a clean suit.’

Sage had a good look at the front paws of the animal. ‘You’d think he would have dug around the body. As – you know, it started to smell. They have a great nose for decomposition.’

‘Good point.’ Lenham waved to one of his colleagues. ‘Get the dog taken over to the station and examined in case he touched the body.’ He turned back to Sage. ‘How’s the retrieval coming on?’

‘Trent is just taking a few more location shots while we work on the grave itself. Megan says she’ll take the body to the mortuary in the morning at the earliest; we’ll be working late. There’s a lot to document.’ She hesitated. ‘What did you mean by “last time”?’

‘Teenager went missing in 1992, right here. Alistair Chorleigh was the last person to see her. She was never found.’ His voice was clipped. ‘We need that body if we’re going to solve this murder. You’d better get on with it, then.’

Sage walked back to the tent, changed her forensic suit for a clean one, and knelt by the corpse again. She reached for a few more leaves at the side of the body and brushed the girl’s hip. The distant sobbing of the woman at the gate was chilling, and the flickering lights brought movement to the gleaming eyes of the dead girl.

2

‘I first heard of Chorleigh House and its ancient burial mounds from my friend, P. Chorleigh, Balliol. I intend to help him excavate the barrows with as little disruption as possible, using my training in archaeology. We hope to add to the sketchy knowledge of earthworks within the Royal Forest.’

Journal of Edwin Masters, Saturday 22nd June 1913

The invitation to excavate an ancient barrow had come at the right time, at least for me. My mother, laid low by a fever, was being nursed by her sister. There was no room for me in our rooms. Instead, I would have been forced to stay in my study in Oxford, and survive on what little work there was clerking for a firm of solicitors. Instead, I was greeted by Peter Chorleigh’s excited note, dashed off with a rough sketch of what he believed to be Bronze Age earthworks. They were in the grounds of his family home in Hampshire, but he had never thought of them as so old or interesting before. I didn’t hesitate, but wrote a letter to my mother and bought a railway ticket to Southampton. I changed there for the halt at Holmsley in the New Forest.

My first view of Chorleigh House was when the driver dropped me off in his horse and trap. It had been a long rattle over forest roads to the house, the drive arching in through a double gate with massive gateposts. The house sat side-on to the road beside a huge striped lawn and shrub beds already covered with roses in bud. The property itself was built of grey stone, the front door under a portico at the top of three shallow steps. Pairs of windows looked out over the garden, and I could see a couple ran through the house to give a view of treetops and sky beyond. A grass tennis court appeared to run along the furthest side of the house beyond an outbuilding or two.

‘Here’s Chorleigh,’ the driver told me, pulling his horse up on the wide circle of gravel in front of the house. ‘That’ll be three shillings.’

I gave him four; I had enjoyed the drive through the forest from Holmsley Station.

‘I suppose you must get a bit of work from the Chorleighs?’ I said, dragging my leather bag off the back.

‘Not much,’ he answered, somewhat curtly. ‘They got motors. Bloody things, shouldn’t be allowed in the forest, that’s what I say. They scare the horses. Two ponies had to be shot last month after they were run down.’

‘I’m sorry to hear that.’ I lifted my satchel off and stood back. ‘Thank you, anyway. I plan to stay a month, but perhaps I shall see you when I leave.’

‘You can get me through the station, they’ve got a telephone there.’ He snapped out a number and started to turn his horse towards the road. Then he stopped, and curiously, looked back. ‘If you need me in a hurry, my niece, Tilly, she’ll always get a message to me. She works in the kitchen here. Mr Chorleigh, he’s a hard man. He’s got a bit of a temper.’

‘I’m sure everything will be fine, but thank you.’ I was baffled by the offer, but thanked him anyway. Then Peter appeared in the open doorway at the front of the house and yelled, ‘Edwin!’ and I was swept off my feet in a bear hug.

Peter is a year younger than me as I started my degree late, and we didn’t seem to have much in common. But in the last years, as we studied our degrees and shared a college, we became close. ‘Comrades under fire,’ Peter called it, as we shivered under the scathing criticism of one of our teachers, the great Sir Charles Latterby. Now our essays are marked, our final examinations are over and we are to spend the summer putting our knowledge to the test before I must return to my mother’s house and find suitable employment.

He led me through a large door into a spacious hallway, with two staircases curving up to a half-landing above.

‘Peter!’ a voice exclaimed, and I turned to see a young woman who resembled him so much I knew she must be his sister.

‘Oh, Molly, there you are!’ He hugged her briefly, and for a moment their faces were close together. She looked like a delicate, feminine version of him, and he caught her arm to draw her towards me. ‘This is Edwin, my closest friend from Oxford.’

Molly held out her hand; I noticed it had smears of paint or ink on it. She almost withdrew it, but I clasped it anyway. She blushed. ‘I’m sorry,’ she murmured. I could see an older man behind her, as dark as his children were fair and even taller than Peter.

‘My father, Mr James Chorleigh,’ Peter said, stooping to pat the two dogs that curved around his feet. ‘Edwin Masters, Father.’

I shook Mr Chorleigh’s hand.

‘You’re welcome,’ he said. ‘Peter, get your friend settled in, then go and see your mother.’ He turned to me, ‘I know you won’t mind my wife not greeting you. She has been unwell.’ I knew she had been ill; a nervous collapse, Peter had said. The youngest child of the family had died from diphtheria the year before, a terrible time for them all, and Mrs Chorleigh had taken to her bed. ‘We are looking forward to your historical discoveries in the grounds. But I don’t want my wife disturbed.’

‘Of course, sir,’ I said. ‘And we won’t spoil your grounds too much.’

He nodded to me and turned away. Peter hefted my leather bag.

‘Come up, Ed, I’ll show you your room.’

‘Then come down for tea,’ Molly said, blushing again.

As we walked up to the landing, I could see it was beautifully lit from above by a domed lantern in the ceiling. It shone on the polished parquet flooring below. ‘This is lovely,’ I managed to say before he caught my arm and dragged me towards one wing.

‘Nice enough. My grandfather put in the wooden flooring downstairs; it’s better with the dogs than carpets everywhere.’ He dragged my case into one of the bedrooms. ‘I’ve put you in here, next to me. My mother is on the other side of the house; she likes the quiet. Now, wash up and come down for some tea,’ he said, putting the bag on the bed. ‘There’s the bathroom across the hall, there’s a towel somewhere – ah, here. I’ll go and see Mother.’ He grimaced. ‘Poor Molls, she’s become Mother’s companion. She doesn’t get out much since Claire died.’

‘That can’t be easy, at her age.’

He leaned against the doorjamb. ‘That’s why you’re here. You will liven us all up with your discoveries and scholarship.’

I almost laughed at that. ‘Me, old sobersides, to liven anyone up?’

‘Well, you’ll liven me up anyway.’ He grasped my arm briefly. ‘I’ve missed you, Ed.’

3

Tuesday 19th March, this year

It had been a long evening’s work uncovering the body and Sage didn’t get back to her mother’s house in Winchester until past midnight. She half registered that Nick was asleep in the spare bed and Max, her eleven-month-old son, startled in his cot when she walked in.

It was a pleasure to lift him, feel him snuggle into her. It didn’t seem possible that River Sloane had ever been alive like this, but the idea made tears gather in the corners of her eyes. Max laid his head against her shoulder and subsided back into sleep. He smelled of shampoo and clean pyjamas and baby and if Nick hadn’t been taking up half the bed, she probably would have snuck Max in with her. She nestled him back between his soft toys and covered him with a blanket. He turned his head and whimpered and she stroked his back.

‘How did it go?’ Nick’s whisper just reached her, but she waited until the baby was completely asleep before she answered.

‘OK. It was all right,’ she murmured back, sliding out of her clothes. She ached from kneeling over the grave for so long. ‘Sad.’ She couldn’t face looking in her bag for more clothes so decided to sleep in her T-shirt. When she slid under the duvet Nick reached for her and curved his body against her back. He was warm; she realised how cold she’d got. ‘Go back to sleep. Love you.’

He buried his face in her hair and kissed her neck. ‘Mm. You too.’

* * *

Sage woke with a start; she must have crashed straight into sleep, and it took a few moments to work out where she was. Mum’s house, the body in the woods, Maxie, Nick. She checked her phone: barely six-thirty, it was still gloomy outside. A tangled memory of running, a body in a well and the girl in the leaves haunted her.

The bed next to her was empty, as was the cot. Nick must have taken the baby downstairs with him. Sage could shower and dress in peace. She could just hear the odd burst of conversation from downstairs, laughter, as she got ready for work. Mum loved Max and he adored her. His giggle met Sage as she walked towards the kitchen at the back of the old terraced house.

Nick appeared in the doorway with a spoon, holding the baby. ‘Put Maxie in his high chair, will you? And taste this.’

She smiled at Max and tasted the porridge. ‘That’s delicious. Hi, baby boy. Do you want some maple syrup like Mummy?’

Max lifted his arms towards her. It was still a wonder to be able to hold him, feel his weight against her. He was just starting to wobble across the room on his feet, which to Sage was a small miracle every day.

‘He eats it as it comes, like me,’ Nick scoffed. ‘It’s just you that needs to drown it in sugar.’

Max waved and burbled something to her. She pulled the high chair out from the wall beside the table. ‘Really, Maxie, are you hungry? Sit in your chair and Nick will get you something to eat. Where’s Sheshe?’

‘Just putting the bin out.’ Nick carried bowls over. He put some toast soldiers on the tray for Max to pick up and drop and throw about, and handed Sage a baby spoon. ‘It’s your turn to get covered. I was still getting porridge out of my hair at lunchtime yesterday.’

Sage’s mother, Yana, walked in and opened her arms for a hug with her daughter. ‘You’re OK?’ she asked after a moment, pushing Sage back to study her face. ‘Saw the case on the news. Terrible.’ It always amazed Sage that Yana had never lost her Kazakh accent, despite living in the UK for nearly forty years.

‘Very sad,’ Sage said, looking at them. Her favourite people, all together. ‘How’s Maxie been?’

‘No trouble, never.’ Her mother beamed. ‘Nick and me, we took him to park.’

‘When do you have to go back to the crime scene?’ Nick mumbled through a spoonful of porridge.

‘I need to be there early. Maxie?’ The baby opened his mouth like a bird and took the porridge off the spoon. He slapped the toast on the tray, some of the bits flying across the table.

Sage’s phone pinged and she reached for it. Trent. Check the 24-hour news.

‘Sorry, Sheshe.’ She switched the small TV on over Yana’s protests. ‘It’s just work.’

She could hear Nick talking to Max. A couple were on a long table flanked by police. Both looked exhausted, red-eyed with fear, especially the father. A voiceover was dispassionate. ‘On Sunday 17th March, Owen and Jenna Sloane appealed for the safe return of their daughter, River, who went missing on Saturday afternoon after 12.30.’

‘If anyone knows anything, please let the police know,’ the woman said. ‘We’re just so worried. She didn’t even tell us where she was going.’ Her face was creased with anxiety, fear, threaded with hope. The father buried his head in his hands and was comforted by his wife. A group portrait flashed up, of the smiling parents, River, another young girl she recognised from outside the garden at Chorleigh House, and a small boy. It took Sage a moment to equate the family portrait with the still, grey body in the leaves. Sage couldn’t imagine how the family were feeling. It must have been terrifying being caught up in a room full of journalists and police; the cameras showed the mother collapsing in tears. The banner scrolling across the bottom of the screen caught Sage’s eye. ‘Body found in New Forest…’ The shot cut away from the appeal to the distant five-bar gate of Chorleigh House. ‘Police are unable to confirm the body found at an address in the New Forest…’ She switched the TV off.

‘That’s awful. I can’t imagine how the parents are coping,’ Nick said. ‘How long will you need to be at the site?’ Nick shook his head at Max, who was cramming his fingers into his mouth after the porridge. ‘You’re going to need a bath, little man.’

Sage gulped a mouthful of tea. ‘They were there yesterday, crying behind the police barrier. I don’t know how long it will go on for. We hadn’t even finished uncovering…’ She looked at Max. ‘Retrieving the victim. Then we have a lot of lab stuff to do.’

‘You do remember I’m going away too?’

‘Of course, that’s why I asked Mum to babysit Max.’ Which was all true, it’s just that where he was going and the reason had slipped her mind. ‘Conference, right?’

He looked back at her, his face grave. ‘No, not a conference. I’m going to see a team ministry. It’s a particularly successful model for other deprived rural areas. I want to see how it works. For the future, if I go for another job.’

Sage filled a spoon for the baby and retrieved bits of chewed toast from the floor. Five-second rule, she decided, and put a couple of the least fluffy ones back on his tray. ‘Porridge, Maxie.’ The baby was adorable; Sage’s whole body seemed to relax when he looked at her. ‘We’re OK living where we are at the moment; we can manage a bit longer. You’re happy at Banstock and I’m finishing my training. Maybe we should move a few things around to make the flat more comfortable. Let me get back to work properly, get the job situation sorted out.’

Yana exchanged looks with Sage and walked out into the hall. Oh. It’s going to be one of those talks. Sage took a gulp of tea to fortify herself.

‘Spending two nights a week in a one-bedroom flat?’ Nick said. ‘Making love on a sofa bed because the baby shares the only bedroom? You visiting the vicarage a few times a month?’

It had all been said before. Sage leaned forward. ‘I love you, you love me. That’s all we have room for at the moment. It’s Max’s home and I have a mortgage. I can’t afford to buy anything bigger and you earn peanuts as a vicar. I still have to find a new career I can fit around a baby. Hopefully, forensic archaeology will work for me and I can look for a permanent job on the mainland. Then we can move in together.’

‘How about Maxie, Sage?’ He sat next to her, looking down at the baby. ‘He’s nearly eleven months old. How does he know who I am if I only visit?’

‘He doesn’t need to see you every day to love you—’

Nick looked down, his face sad. ‘I want to see you every day. And I want to be Max’s dad. I miss you both in the week.’

‘I miss you too—’ Her mobile phone rang. ‘I’m sorry, I need to get this, it’s Trent.’

‘Sage?’ The signal wasn’t good. ‘I need to do the survey at Chorleigh House before the dew goes. Will you be there?’

‘On my way, should be half an hour.’

Nick silently handed her the phone charger and her work lanyard. She wolfed down the last of her porridge. It had gone cold.

He put his hand on her shoulder. ‘I’m still not sure that working on a murder won’t bring back stuff from last year. Flashbacks.’

Just the word felt like a cup of cold water down her spine. ‘I know,’ she said, stalled. ‘I’ve been studying forensics to get it out of my system. I think this will help, I really do. It’s sad but it’s someone else’s child, you know?’

He reached his arms around her, holding her until she curved into him and hugged him back. ‘I remember how you were when you found the body in the well last year. It’s bound to remind you.’

She smiled at him, having to tilt her chin up as he was a little taller. ‘It might be a good thing. Then I’ll have something to tell that counsellor you’re always telling me to see.’ He smelled like the sea, fresh scents coming off his clean jumper. ‘I’ll be careful, and I’ll tell you all about it.’

He kissed her. ‘I love you, Sage.’ He let go slowly, leaving her a bit puzzled.

‘I love you too. Are you OK?’

‘Just not looking forward to the long drive. I’ll be in Cambridge tonight seeing my parents, then I’ll do the rest tomorrow.’

She couldn’t even remember where he was driving to, and didn’t want him to think she didn’t care. God, I’ve become so selfish. ‘Well, I hope you have a great time. I better go, I don’t want to be late.’ She kissed Max on the top of his head, the only part of him that didn’t look sticky. ‘Love you, Maxie Bean. Be good for Nana.’

* * *

The New Forest looked lovely in the early morning light. Leaves were just starting to unfurl from some of the saplings at the edge of the road, and there were catkins everywhere. Sage could feel the tension building as she turned towards Fairfield then into the lane where Chorleigh House was set in the forest. A dozen cars were pulled up on the grass verges along the road and a line of police tape held back people with cameras, some even snapping a few pictures of her as she was waved through and pulled into the drive.

The property had a paling fence held together with wire and a wide drive with two brick gateposts, both in poor repair. The five-bar gate was pulled partly across, narrowing the gap onto a large expanse of gravel. The area was full of weeds and brambles encroaching from the edges. To the left was a raised bed built of the same stone as the house, rampant with the frost-blackened skeletons of bracken. On the right the house was grey, the windows dark.

As she walked in the low light she realised how fresh the air was, the breeze cold on her neck. A tall, thin man was pacing across the drive, counting each step aloud. ‘Trent!’

He grinned at her through a dark beard. ‘There you are. How did the grave site work go?’

‘It’s still going on. We got most of the leaves last night and they are hoping to retrieve the body this morning. What are you doing – have you started the survey?’

‘No, I’m getting ready to attempt an aerial assessment before the frost melts and the dew dries. They are highlighting the footprints into the woods.’ He squinted up through his glasses. ‘The sun’s starting to come over the hill, these shadows won’t last much longer.’

‘Drones. We didn’t use them in my training,’ Sage said as they moved onto the grass. She looked along Trent’s arm, pointing into the woodland. A number of footprint trails converged on the area of the body, clearly visible in the frost. There was a flattened path leading between the bare trees.

‘There are about thirty-eight acres of woodland associated with the property,’ he said, pulling a map out of his backpack. He shook it open and folded it so she could see the area better. ‘All of this belongs to Chorleigh House.’ His finger circled the irregular shape, then pointed at two star shapes. ‘These are the historical barrows, probably Bronze Age. They were excavated a hundred years ago. I’ve been trying to get to see them.’

‘Wow. How much is left?’

Trent grinned at her. ‘Quite a lot. Back in the early nineteen hundreds an archaeology student dug up a burial in the complete earthwork. They “restored” the mound afterwards, which probably means they just chucked the soil back.’

Sage looked back at him. ‘I’m guessing this was not a permitted excavation?’

‘No, but they hadn’t even identified it as a scheduled monument at that time. But there’s a real legend around the barrows.’ He looked up at the house, which looked like it was leaning over the garden. ‘The archaeologist in charge of the dig vanished. The locals call the place haunted; they claim he disturbed an ancient curse.’

She shrugged. ‘I don’t believe in curses, ancient or otherwise. The earthworks look like they are right on the boundary of the adjoining farmland. There could be banks and ditches associated with the barrows. I wonder how much has been ploughed away. Do we know if they found anything on the original dig?’

‘That’s the strange thing,’ Trent answered. ‘I haven’t found many records yet. And the family was cursed in a way. Alistair Chorleigh’s having a tough time of it; he’s been interviewed all night but they have to release him later or apply for an extension. They just don’t have enough evidence yet, which is where we come in.’ He looked up. ‘Do you see where the leaves came from?’

She turned around, looking for evergreen trees that weren’t just covered in ivy. ‘None nearby but it’s dark in the woodland. There’s been a lot of foot traffic in and out along that path. Oh, DCI Lenham.’

Lenham stepped onto the pad behind her. ‘Good morning. The old lady who found the body said she only went as far as the grave to get her dog.’

Sage looked back across the long grass and bracken. ‘Did her dog touch the body? There are scratches on one of the hands.’

‘Yes, the owner said it ran off and wouldn’t come back.’ Lenham shivered, shrugged his coat around his ears. ‘She didn’t like to trespass because Chorleigh has got a bit of a nasty reputation locally. When she couldn’t get it to come back to the road, she had to go in to get it. The animal had taken the leaves off part of the girl’s hand.’

Sage surveyed the woodland. It was dense and didn’t look well managed. Brambles had filled in most of the undergrowth and she could see rabbit and deer droppings on the slight path. There were definitely discrete areas of flattening in the shimmering white over the grass.

‘Are those the footprints you saw last night?’ she asked.

‘Yes.’ Trent pointed up to the sky. ‘I’ll get the drone up and we’ll get some footage. Can Megan spare you for half an hour?’

Sage looked around the garden. ‘I’m sure she can, I came early just to help you.’ Apart from islands of overgrown shrubs in the bracken and grass, there was little evidence it had been cultivated recently. The trees gathered into a wall of shadows. ‘I can see how a view from above will show features you can’t see from the ground.’

Trent grinned at her. ‘The police love our aerial shots. I want to get some before they start exploring the grounds.’ He turned to DCI Lenham. ‘If you could get your officers to stand back, I can get the drone up.’

‘No problem.’ Lenham hunched his shoulders up. ‘This place gives me the creeps.’ He walked towards the front of the house, waving at three officers who followed him.

The long grass and bracken were covered with a shimmering lace of spiders’ webs hung with droplets as the frost melted. A few lime-green buds were just unfolding. Sage could see some areas were flattened in ovals in a staggered line of prints, still visible in the light frost. Trent started to set the drone up in the centre of the lawn.

He waved at Sage. ‘Stand well back. I’m taking off.’

The drone whined and started hovering over the grass where he had placed it. The grave site itself was still covered with the forensic tent. As the machine rose Trent showed her the white tent in the green of the grounds on his tablet. ‘Look.’

Greener areas had less frost, and as the image sharpened Sage could see footprints criss-crossing the shaded grass into gaps between the trees. They were roughly oval and the flattened grass distorted the shape.

Sage pointed at the screen. ‘How do we know they aren’t animal prints?’

Trent brought the drone down until it hovered a few metres over the edge of the woodland. He zoomed in on one of the marks. ‘There are heel and toe impressions on a few of them. Not to mention there’s just one pair of prints, no back feet. Although you’re right, that doesn’t always mean a biped; deer often walk in their own prints. They are fuzzy – they’ve been here at least eighteen hours and possibly from the night before, they are just rough shapes. Quite a long stride. Hopefully the ground will give us a better impression if we can find a muddy patch and we might find a trace.’

Sage bounced on her heels, rubbed her hands down her arms to warm herself up. ‘Maybe they went into the wood to gather the leaves?’

‘It’s possible.’ Trent manoeuvred the drone so it swooped over the ground towards the drive. ‘My guess is they drove here, parked maybe on the drive or the verge along the road. The gravel wouldn’t leave the same prints as flattened grass and the gate’s always open but it would make a lot of noise.’

‘They then carried the body across the garden? Anyone driving past could have seen them. And what about the homeowner?’

‘I suspect it was dark, in the middle of the night, and a quiet road because that’s how most people dispose of victims. And the homeowner is a suspect himself. But look what I found yesterday.’

The drone swerved along the drive over the road, absent of cars as it was still closed off, the press kept behind police tape. It slid east along the grass verge, then turned back and covered the area to the west. There were multiple tyre lines diagonal to the grass verges but only one parallel to the road. They showed patches of white, like paint.

Trent pointed it out. ‘The police made a cast of these tracks. We’ll check to make sure these aren’t from the press or the dog walker, but I think the perp could have parked outside, carried her in. She didn’t look heavy.’

‘Chorleigh wouldn’t have needed to park on the verge. He could have pulled onto the drive.’

‘Yes, and anyone could have driven onto the grass since we last had heavy rain. Walkers, or someone who stopped to look at a map or got a puncture. But they look fresh.’ He swung the drone around again, letting it alight gently on the lawn. ‘You don’t fancy Chorleigh for it, then?’

‘I don’t know. It seems stupid, to bury the body in your own garden and just a foot deep.’

‘Stupid, yes. Unlikely – I don’t know. Murderers are stupid, in my experience. He might not have been thinking straight, he’s a drunk. Who knows what he was thinking? The leaves could have been laid on with remorse.’

Sage looked back at the white tent. ‘She was found by a dog walker, you said. Why not by Chorleigh’s own dog? Surely he would have smelled a stranger, let alone a body.’

‘According to Lenham, Chorleigh says he doesn’t let his dog off the lead at night because the gate is always open, apparently it’s stuck. The walker couldn’t get her collie to come back so she came in to get it. When she saw what her dog had uncovered she panicked, flagged down an elderly motorist. She was in such distress he called an ambulance and the police, in case her story was true.’

‘It’s a good job the dog didn’t disturb the burial too much.’

Trent raised the drone high above the trees to get a wider view. ‘We see animal damage a lot. Foxes and badgers can disarticulate a body quite fast in the summer.’

She felt queasy again. ‘Enough information. Do we know when they can remove the body?’

‘It won’t be long. Forensics want another look at the grave in daylight before we start excavating the cut itself, the digging.’

‘Do we need to be involved in that?’ Two more people were walking down the drive, dressed in forensic suits. She looked back at the dark windows of the house.

‘They look at it primarily as a source of trace evidence, so no, they won’t want us. They’ll look for clothing fibres, as she was undressed, and anything the murderer might have dropped. We’ll look at the wider scene, how the hole was dug, where the spoil was dropped, how the hole was filled in.’

‘In this case, where did they get the leaves from?’ Sage said. ‘I don’t see many evergreens.’

He looked around. ‘Not from this area, anyway. We’ll search the whole grounds. We will also look into whether they left any more footmarks or evidence, and do the wider survey to create an accurate site plan.’ The drone’s engine, hovering overhead, hummed like a large bee. The machine lifted high above the trees, and Trent flew it a few hundred yards south of the drive. He held the tablet out to Sage. ‘Watch this.’

The trees looked odd from above, the branches reaching for the drone. It disturbed a blackbird which took off with angry screeching. A jay flew under the camera in a flap of black, white and peach feathers, a flash of blue. She watched as the drone slowly moved along the boundary of the woodland and the field beyond. ‘Are those – the barrows?’ There were two raised areas, one classically a round-ended, elongated rectangle, and the other about half the size with an oval end. The smaller one had a few small shrubs leaning from one end and a large flat area on the surface.

‘Yes,’ Trent said. ‘The site’s called Hound Butt on Victorian surveys. It was pretty well vandalised in the early nineteen hundreds, by modern standards anyway.’

‘Vandalised? Do you mean when the archaeologist who went missing dug it up?’ Sage followed the view as the drone swooped over the intact one.