Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Merrily Watkins Series

- Sprache: Englisch

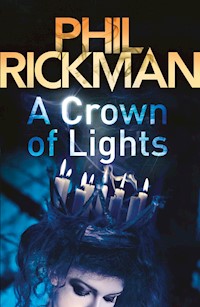

Single mother and Diocesan Exorcist Merrily Watkins must keep the peace in rural Hereford, quelling a modern witch hunt, and a killer with an old tradition to guard... Ancient history, violent deaths, feuds, intrigues and murder. A most original sleuth. - The Times When a pagan couple buy a ruined church on the Welsh Border, there's an extreme reaction from the local fundamentalist priest. Is it a hate campaign or a nightmarish modern witch-hunt? Merrily Watkins is sent in to keep the lid on the cauldron and uncovers the sinister dynamics of the isolated village of Old Hindwell.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 738

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A Crown of Lights

PHIL RICKMAN was born in Lancashire and lives on the Welsh border. He is the author of the Merrily Watkins series, and The Bones of Avalon. He has won awards for his TV and radio journalism and writes and presents the book programme Phil the Shelf for BBC Radio Wales.

ALSO BY

PHILRICKMAN

THE MERRILY WATKINS SERIES

The Wine of AngelsMidwinter of the SpiritA Crown of LightsThe Cure of SoulsThe Lamp of the WickedThe Prayer of the Night ShepherdThe Smile of a GhostThe Remains of an AltarThe Fabric of SinTo Dream of the Dead

Coming soon...The Secrets of Pain

OTHER BOOKS

The Bones of Avalon

PHILRICKMAN

A Crown of Lights

First published in Great Britain in 2001 by Macmillan.

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2011by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Phil Rickman, 2001.

The moral right of Phil Rickman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. All characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-0-85789-011-5eBook ISBN: 978-0-85789-018-4

Printed in Great Britain.

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26-27 Boswell StreetLondon WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Part One

1 The Local People

2 Livenight

3 Loved Like That

4 Repaganization

5 Every Pillar in the Cloister

6 Unkind Sky

7 Possession

8 The E-Word

9 Visitor

10 Nightlife of Old Hindwell

11 No Ghosts, No God

Part Two

12 Bear Pit

13 A Surreal Memory

14 Armageddon

15 Fairground

16 Lurid Bit

17 Revelations

18 Cold, Earthly, Rational...

19 Abracadabra

20 Blessed Beneath the Wings of Angels

21 Lord Madoc

22 Wisp

Part Three

23 Tango with Satan

24 Against the World

25 Cyst

26 Demonstration of Faith

27 Spirit of Salem

28 A Humble Vessel

29 Dark Glamour

30 Handmaiden

31 Jewel

32 Potion

33 The Adversary

34 Kali

35 This is History

36 The Atheist

37 Night Hag

Part Four

38 The Real Thing

39 Witches Don’t Cry

40 Key to the Kingdom

41 The Kindling in the Forest

42 Raising the Stakes

43 Mitigating Circumstances

44 Feel the Light

45 Stupid Wires

46 Nine Points

Part Five

47 Breath of the Dragon

48 Black Christianity

49 Cashmere and Tweed

50 Scumbag

51 Laid to Unrest

52 Beast is Come

53 Snakeskin

54 No God’s Land

55 Grey, Lightless

56 Each of my Dyings

57 In Shock

58 The Woman Clothed with the Sun

59 Damage

60 Lamplit

Notes and credits

Part One

Goddess worshippers... are particularly concerned with creativity, intuition, compassion, beauty and cooperation. They see nature as the outward and visible expression of the divine, through which the goddess may be contacted. They have therefore more to do with ecology and conservationism than with orgies and are often gentle worshippers of the good in nature.

Deliverance (ed. Michael Perry)The Christian Deliverance Study Group

1

The Local People

BETTY WAS DETERMINED To Keep the lid on the cauldron for as long as possible, which might just – the way she’d been feeling lately – mean for ever.

The arrival of the old box was no help.

It turned up on the back step at St Michael’s only a few days after they had moved into the farmhouse and a week after Betty turned twenty-seven. It wasn’t her kind of present. It seemed like a direct threat – or at least confirmation that their new life was unlikely to be the idyll that Robin expected.

For Betty, the first inkling of this – if you could call such experiences inklings – had already occurred only minutes before on that same weird evening.

The new year had been blown in, battered and dripping, and the wind and the rain still bullied the hills. Tonight, though, it looked like being clean and still and iron-hard with frost, and Robin had persuaded Betty to come with him to the top of the church tower – their church tower – to witness the brilliant winter sunset.

This was the first time she’d been up there, and the first time she’d ever been into the church out of daylight hours. It wasn’t yet five p.m. but evening still came early to the Radnor Valley in late January – the dark side of Candlemas – and Robin was leaning over the cracked parapet to watch the final bloodrush over an otherwise unblemished sky.

‘I guess what we oughta do,’ he murmured playfully, ‘is shake down that old moon.’

The Forest was laid out before them: darkening storybook hills, bearded with bracken. There were few trees – misleadingly, it had been named forest in the medieval sense of a place for hunting. Betty wondered how much of that still went on: the lamping of hares, the baiting of badgers. Maybe some night Robin would be standing up here and would see a party of silent men with guns and dogs. And then the shit would fly.

‘So, uh, how would you...’ Robin straightened up, slapping moss from his hands, ‘... how would you feel about that?’

‘You mean now, don’t you?’ With both hands, Betty pushed back her wild, blonde hair. She backed away from the edge, which had got her thinking about the death of Major Wilshire. Down below, about six feet out from the base of the tower, two flat tombstones had been exposed beneath a bush blasted back by the gales. That was probably where he’d fallen. She shivered. ‘You actually mean out here?’

He shrugged. ‘Why not?’ He wore his orange fleece and his ludicrous flattened fez-thing with tiny mirrors around the side. The way Betty saw it, Robin Thorogood, having grown up in America, had yet to develop a functioning sense of the absurd.

‘Why not?’ Betty didn’t remember exactly when ‘shaking down the moon’ had become his personal euphemism for sex, but she didn’t altogether care for the term. ‘Because this is, you know, January?’

‘We could bring up blankets.’ Robin did his abandoned puppy face.

Which no longer worked on Betty. ‘Mother of God, I bet it’s not even safe! Look at the floor... the walls! We wind up down in the bloody belfry, in a cloud of plaster dust, with multiple fractures, what happens then?’

‘Aw, come on. It’s been here for six... eight centuries. Just because—’

‘And probably falling apart for most of the last hundred years!’

Betty gripped one of the battlements, then let go quickly in alarm, convinced for a second that a lump of mortar, or whatever medieval mixture those old masons used, was actually moving underneath it. The entire tower could be crumbling, for all they knew; their funds had run to only a cursory survey by a local bloke who’d said, ‘Oh, just make sure it doesn’t fall down on anybody, and you’ll be all right.’ They ought to bring in a reliable builder to give the place a going-over before they contemplated even having a picnic up here. If they could ever afford a builder, which seemed unlikely.

Robin stood warrior-like, with his back to the fallen sun, and she knew that in his mind he was wearing animal skins and there was a short, thick blade at his hip. Very like the figure dominating his painting-in-progress: Lord Madoc the intergalactic Celt, hero of Kirk Blackmore’s Sword of Twilight. Seven hundred pages of total bollocks, but it was misty cover designs for the likes of Blackmore that were going to have to meet the mortgage premiums until Betty dared come out locally as a herbalist and healer, or whatever was socially acceptable.

‘Just I had a sensation of what it would be like afterwards,’ the great visionary artist burbled on, unabashed, ‘lying here on our backs, watching the swirl of the cosmos, from our own—’

‘Whereas I’m getting a real sensation of watching the swirl of tomato soup with croutons.’ Betty moved to the steps, took hold of the oily rope, feeling about with a trainered foot for the top step. ‘Come on. We’ll have years to do all that.’

Her words lingered in a void as hollow as these ruins. Betty could not lose the feeling that this time next year they would not even be here.

‘You know your trouble?’ Robin suddenly yelled. ‘You’re becoming sensible before your time.’

‘What?’ She spun at him, though knowing that he’d spoken without thinking... that it was just petulance... that she should let it go.

‘Well...’ He looked uneasy. ‘You know...’

‘No, I don’t.’

‘OK, OK...’ Making placatory patting gestures with his hands, too late. ‘Wrong word, maybe.’

‘No, you’ve said it now. In normal life we’re not supposed to be sensible because we’re living the fantasy. Like we’re really not supposed to bother about everyday stuff like falling to our deaths down these bloody crumbling steps, because—’

‘There’s a guy over there,’ Robin said. ‘In the field down by the creek.’

‘It’s a brook.’ Betty paused on the top step.

‘He’s looking up.’ Robin moved back to the rim of the tower. ‘He’s carrying something.’

‘A spear of light, perhaps?’ Betty said sarcastically. ‘A glowing trident?’

‘A bag, I think. A carrier bag. No, he’s not in the field. I believe he’s on the footway.’

‘Which, of course, is a public footpath – which makes him entitled to be there.’

‘Naw, he’s checking us out.’ The sunset made unearthly jewels out of the tiny round mirrors on Robin’s fez. ‘Hey!’ he shouted down. ‘Can I help you?’

‘Stop it!’ Sometimes Betty felt she was a lot older than Robin, instead of two years younger. Whole lifetimes older.

‘He went away.’

‘Of course he did. He went home to warm his bum by a roaring fire of dry, seasoned hardwood logs.’

‘You’re gonna throw that one at me all night, I can tell.’

‘Probably. While we’re sitting with our coats on in front of a lukewarm stove full of sizzling green pine.’

‘Yeah, yeah, the wood guy ripped me off. He won’t do it again.’

‘Dead right he won’t. First rule of country living: show them, from the very start, that you’re not an urban innocent.’

Robin followed her down the narrow, broken stone steps. ‘While being careful not to antagonize them, right?’

Betty stopped on the spiral, looked back up over her shoulder. It was too dark to see his face.

‘Sooner or later,’ she said, ‘there is going to be antagonism – from some of them at least. It’s a phase we’re going to have to go through and come out the other side with some kind of mutual respect. This is not Islington. This is not even Shrewsbury. In Radnorshire, the wheels of change would grind exceeding slow, if they’d ever got around to inventing the wheel.’

‘So what you’re saying, making converts could take time?’

‘We won’t live that long. Tolerance is what we aspire to: the ultimate prize.’

‘Jeez, you’re soooo— Oh, shit—’

Betty whirled round. He’d stumbled on a loose piece of masonry, was hanging on to the hand-rope.

‘You OK?’

‘Third-degree rope burn, is all. I imagine the flesh will grow back within only weeks.’

She thought of Major Wilshire again and felt unsettled.

‘I was born just twenty miles from here,’ she said soberly. ‘People don’t change much in rural areas. I don’t want to cause offence, and I don’t think we need to.’

‘You changed.’

‘It’s not the same. I’m not from yere, as they say.’ Betty stepped out of the tower doorway and onto the frozen mud of what she supposed had once been the chancel. ‘My parents just happened to be working here when I was born. They were from Off. I am, essentially, from Off.’

‘Off what?’

‘That’s what they say. It’s their word. If you’re an immigrant you’re “from Off”. I’d forgotten that. I was not quite eleven when we left there. And then we were in Yorkshire, and Yorkshire flattens all the traces.’

Curtains of cold red light hung from the heavens into the roofless nave. When Robin emerged from the tower entrance, she took his cold hand in her even colder ones.

‘Sorry to be a frigid bitch. It’s been a heavy, heavy day.’

The church was mournful around her. It was like a huge, blackened sheep skeleton, with its ribs opened out. Incongruously, it actually came with the house. Robin had been ecstatic. For him, it had been the deciding factor.

Betty let go of Robin’s hand. She was now facing where the altar must have been – the English side. And it was here, on this frigid January evening, that she had the flash.

A shivering sense of someone at prayer – a man in a long black garment, stained. His face unshaven, glowing with sweat and an unambiguous vivid fear. He’d discovered or identified or been told something he couldn’t live with. In an instant, Betty felt she was suffocating in a miasma of body odour and anguish.

No! She hauled in a cold breath, pulling off her woollen hat, shaking out her sheaf of blonde hair. Go away. Don’t want you.

Cold. Damp. Nothing else. Shook herself like a wet dog. Gone.

This was how it happened. Always without warning, rarely even a change in the temperature.

‘And it’s not officially a church any more,’ Robin was reminding her – he hadn’t, of course, sensed a thing. ‘So this is not about causing offence. Long as we don’t knock it down, we can do what we like here. This is so cool. We get to reclaim an old, pagan sacred place!’

And Betty thought in cold dismay, What kind of sacred is this? But what she actually said, surprised at her own calmness, was, ‘I just think we have to take it slowly. I know the place is decommissioned, but there’re bound to be local people whose families worshipped here for centuries. And whose grandparents got married here and... and buried, of course.’

There were still about a dozen gravestones and tombs visible around the church and, although all the remains were supposed to have been taken away and reinterred after the diocese dumped the building itself, Betty knew that when they started to garden here they’d inevitably unearth bones.

‘And maybe,’ Robin said slyly, ‘just maybe... there are people whose distant ancestors worshipped here before there was a Christian church.’

‘You’re pushing it there.’

‘I like pushing it.’

‘Yeah,’ Betty agreed bitterly.

They moved out of the ruined church and across the winterhard field and then over the yard to the back of the house. She’d left a light on in the hall. It was the only light they could see anywhere – although if they walked around to the front garden, they would find the meagre twinklings of the village of Old Hindwell dotted throughout the high, bare hedge.

She could hear the rushing of the Hindwell Brook, which almost islanded this place when, like now, it was swollen. There’d been weeks of hard rain, while they’d been making regular trips back and forth from their Shrewsbury flat in Robin’s cousin’s van, bringing all the books and stuff and wondering if they were doing the right thing.

Or at least Betty had. Robin had been obsessed from the moment he saw the ruined church and the old yew trees around it in a vague circle and the mighty Burfa Camp in the background and the enigmatic Four Stones less than a couple of miles away. And when he’d heard of the recent archaeological discoveries – the indications of a ritual palisade believed to be the second largest of its kind in Europe – it had blown him clean away. From then on, he needed to live here.

‘There you go.’ He bent down to the back doorstep. ‘What’d I tell ya?’ He lifted up something whitish.

‘What’s that?’

‘It is a carrier bag – Tesco, looks like. The individual by the river had one with him. I’m guessing this is it.’

‘He left it on our step?’

‘House-warming present, maybe? It’s kinda heavy.’

‘Put it down,’ Betty said quietly.

‘Huh?’

‘I’m serious. Put it back on the step, and go inside, put on the lights.’

‘Jeeeeeeez!’ Robin tossed back his head and howled at the newborn moon. ‘I do not understand you! One minute I’m over reacting – which, OK, I do, I overreact sometimes, I confess – and this is some harmless old guy making his weary way home to his humble fireside... and the next, he’s like dumping ten pounds of Semtex or some shit—’

‘Just put it down, Robin.’

Exasperated, Robin let the bag fall. It clumped solidly on the stone. Robin unlocked the back door.

Betty waited for him to enter first. She wouldn’t touch the bag.

It was knotted at the top. She watched Robin wrench it open. A sheet of folded notepaper fell out. He spread it out on the table and she read the type over his shoulder.

Dear Mr and Mrs Thorogood,

In the course of renovation work by the previous occupants of your house, this receptacle was found in a cavity in the wall beside the fireplace. The previous occupants preferred not to keep it and gave it away. It has been suggested you may wish to restore it to its proper place.

With all good wishes,

The Local People

‘ “The Local People”?’

Robin let the typewritten note flutter to the tabletop. ‘All of them? The entire population of Old Hindwell got together to present the newcomers with a wooden box with...’ He lifted the hinged lid, ‘... some paper in it.’

The box was of oak. It didn’t look all that old. Maybe a century, Betty thought. It was the size of a pencil box she’d had as a kid – narrow, coffin-shaped. You could probably fit it in the space left by a single extracted brick.

She was glad there was only paper in there, not... well, bones or something. She’d never seriously thought of Semtex, only bones. Why would she think that? She found she was shivering slightly, so kept her red ski jacket on.

Robin was excited, naturally: a mysterious wooden box left by a shadowy stranger, a cryptic note... major, major turn-on for him. She knew that within the next hour or so he’d have found the original hiding place of that box, if he had to pull the entire fireplace to pieces. He’d taken off his fleece and his mirrored fez. The warrior on the battlements had been replaced by the big schoolboy innocent.

He flicked on all the kitchen lights – just dangling bulbs, as yet, which made the room look even starker than in daylight. They hadn’t done anything with this room so far. There was a Belfast sink and a cranky old Rayburn and, under the window, their pine dining table and chairs from the flat. The table was much too small for this kitchen; up against the wall, under a window full of the day’s end, it looked like... well, an altar. For which this was not the correct place – and anyway, Betty was not yet sure she wanted an altar in the house. Part of the reason for finding a rural hideaway was to consider her own future, which – soon she’d have to confess to Robin – might not involve the Craft.

‘The paper looks old,’ Robin said. ‘Well... the ink went brown.’

‘Gosh, Rob, that must date it back to... oh, arguably pre-1980.’

He gave her one of those looks which said: Why have you no basic romance in you any more?

Which wasn’t true. She simply felt you should distinguish between true insight and passing impressions, between fleeting sensations and real feelings.

The basic feeling she had – especially since her sense of the praying man in the church – was one of severe unease. She would rather the box had not been delivered. She wished she didn’t have to know what was inside it.

Robin put the paper, still folded, on the table and just looked at it, not touching. Experiencing the moment, the hereness, the nowness.

And the disapproval of his lady.

All right, he’d happily concede that he loved all of this: the textures of twilight, those cuspy, numinous nearnesses. He’d agree that he didn’t like things to be over-bright and clear cut; that he wanted a foot in two countries – to feel obliquely linked to the old worlds.

And what was so wrong with that? He looked at the wild and golden lady who should be Rhiannon or Artemis or Titania but insisted on being called the ultimately prosaic Betty (this perverse need to appear ordinary). She knew what he needed – that he didn’t want too many mysteries explained, didn’t care to know precisely what ghosts were. Nor did he want the parallel world of faerie all mapped out like the London Underground. It was the gossamer trappings and wrappings that had given him a profession and a good living. He was Robin Thorogood: illustrator, seducer of souls, guardian of the softly lit doorways.

The box, then... Well, sure, the box had been more interesting unopened. Unless the paper inside was a treasure map.

He pushed it towards Betty. ‘You wanna check this out?’

She shook her head. She wouldn’t go near it. Robin rolled his eyes and picked up the paper. It fell open like a fan.

‘Well, it’s handwritten.’ He spread it flat on the tabletop.

‘Don’t count on it,’ Betty said. ‘You can fake all kinds of stuff with computers and scanners and paintboxes. You do it all the time.’

‘OK, so it’s a scam. Kirk Blackmore rigged it.’

‘If it was Kirk Blackmore,’ Betty said, ‘the box would have ludicrous runes carved all over it and when you opened it, there’d be clouds of dry ice.’

‘I guess. Oh no.’

‘What’s up?’

‘It’s some goddamn religious crap. Like the Jehovah’s Witnesses or one of those chain letters?’

‘OK, let me see.’ Betty came round and peered reluctantly at the browned ink. ‘ “In the name of the Father, Son and Holy Ghost, amen, amen, amen...” Amen three times.’

‘Dogmatic.’

‘Hmmm.’ Betty read on in silence, not touching the paper. She was standing directly under one of the dangling light-bulbs, so her hair was like a winter harvest. Robin loved that her hair seemed to have life of its own.

When she stepped away, she swallowed.

He said hoarsely, ‘What?’

‘Read.’

‘Poison pen?’

She shook her head and walked away toward the rumbling old Rayburn stove.

Robin bent over the document. Some of it was in Latin, which he couldn’t understand. But there was a row of symbols, which excited him at once.

Underneath, the words in English began. Some of them he couldn’t figure out. The meaning, however, was plain.

In the name of the Father Son and Holy Ghost Amen Amen Amen...

O Lord, Jesus Christ Saviour Salvator I beseech the salvation of all who dwell within from witchcraft and from the power of all evil men or women or spirits or wizards or hardness of heart Amen Amen Amen... Dei nunce... Amen Amen Amen Amen Amen.

By Jehovah, Jehovah and by the Ineffable Names 17317... Lord Jehovah... and so by the virtue of these Names Holy Names may all grief and dolor and all diseases depart from the dwellers herein and their cows and their horses and their sheep and their pigs and poultry without any molestation. By the power of our Lord Jesus Christ Amen Amen... Elohim... Emmanuel...

Finally my brethren be strong in the Lord and in the power of His might that we may overcome all witches spells and Inchantment or the power of Satan. Lord Jesus deliver them this day – April, 1852.

Robin sat down. He tried to smile, for Betty’s sake and because, in one way, it was just so ironic.

But he couldn’t manage a smile; he’d have to work on that. Because this was a joke, wasn’t it? It could actually be from Kirk Blackmore or one of the other authors, or Al Delaney, the art director at Talisman. They all knew he was moving house, and the new address: St Michael’s Farm, Old Hindwell, Radnorshire.

But this hadn’t arrived in the mail. And also, as Betty had pointed out, if it had been from any of those guys it would have been a whole lot more extreme – creepier, more Gothic, less homespun. And dated much further back than 1852.

No, it was more likely to be from those it said it was from.

The Local People – whatever that meant.

Truth was they hadn’t yet encountered any local local people, outside of the wood guy and Greg Starkey, the London-born landlord at the pub where they used to lunch when they were bringing stuff to the farm, and whose wife had come on to Robin one time.

Betty had her back to the Rayburn for warmth and comfort. Robin moved over to join her. He also, for that moment, felt isolated and exposed.

‘I don’t get this,’ he said. ‘How could anyone here possibly know about us?’

2

Livenight

THERE WERE FOUR of them in the hospital cubicle: Gomer and Minnie, and Merrily Watkins... and death.

Death with a small ‘d’. No angel tonight.

Merrily was anguished and furious at the suddenness of this occurrence, and the timing – Gomer and Minnie’s wedding anniversary, their sixth.

Cheap, black joke. Unworthy of You.

‘Indigestion...’ Gomer was squeezing his flat cap with both hands, as if wringing out a wet sponge, and staring in disbelief at the tubes and the monitor with that ominous wavy white line from a thousand overstressed hospital dramas. ‘It’s just indigestion, her says. Like, if she said it enough times that’s what it’d be, see? Always works, my Min reckons. You tells the old body what’s wrong, you don’t take no shit – pardon me, vicar.’

The grey-curtained cubicle was attached to Intensive Care. Minnie’s eyes were closed, her breathing hollow and somehow detached. Merrily had heard breathing like this before, and it made her mouth go dry with trepidation.

It’s rather a bad one, the ward sister had murmured. You need to prepare him.

‘Let’s go for a walk.’ Merrily plucked at the sleeve of Gomer’s multi-patched tweed jacket.

She thought he glanced at her reproachfully as they left the room – as though she had the power to intercede with God, call in a favour. And then, from out in the main ward, he looked back once at Minnie, and his expression made Merrily blink and turn away.

Gomer and Minnie: sixty-somethings when they got married, the Midlands widow and the little, wild Welsh-borderer. It was love, though Gomer would never have used the word. Equally, he’d never have given up the single life for mere companionship – he could get that from his JCB and his bulldozer.

He and Merrily walked out of the old county hospital and past the building site for a big new one – a mad place to put it, everyone was saying; there’d be next to no parking space except for consultants and administrators; even the nurses would have to hike all the way to the multi-storey at night. In pairs, presumably, with bricks in their bags.

Merrily felt angry at the crassness of everybody: the health authority and its inadequate bed quota, the city planners who seemed bent on gridlocking Hereford by 2005 – and God, for letting Minnie Parry succumb to a severe heart attack during the late afternoon of her sixth wedding anniversary.

It was probably the first time Gomer had ever phoned Merrily – their bungalow being only a few minutes’ walk away. It had happened less than two hours ago, while Merrily was bending to light the fire in the vicarage sitting room, expecting Jane home soon. Gomer had already sent for an ambulance.

When Merrily arrived, Minnie was seated on the edge of the sofa, pale and sweating and breathless. Yow mustn’t... go bothering about me, my duck, I’ve been through... worse than this. The TV guide lay next to her on a cushion. An iced sponge cake sat on a coffee table in front of the open fire. The fire was roaring with life. Two cups of tea had gone cold.

Merrily bit her lip, pushing her knuckles hard into the pockets of her coat – Jane’s old school duffel, snatched from the newel post as Merrily was rushing out of the house.

They now crossed the bus station towards Commercial Road, where shops were closing for the night and most of the sky was a deep, blackening rust. Gomer’s little round glasses were frantic with city light. He was urgently reminiscing, throwing up a wall of vivid memories against the encroaching dark – telling Merrily about the night he’d first courted Minnie while they were crunching through fields and woodland in his big JCB. Merrily wondered if he was fantasizing, because it was surely Minnie who’d forced Gomer’s retirement from the plant hire business; she hated those diggers.

‘... a few spare pounds on her, sure to be. Had the ole warning from the doc about that bloody collateral. But everybody gets that, ennit?’

Gomer shuffled, panting, to a stop at the zebra crossing in Commercial Road. Merrily smiled faintly. ‘Cholesterol. Yes, everybody gets that.’

Gomer snatched off his cap. His hair was standing up like a small white lavatory brush.

‘Her’s gonner die! Her’s gonner bloody well snuff it on me!’

‘Gomer, let’s just keep praying.’

How trite did that sound? Merrily closed her eyes for a second and prayed also for credible words of comfort.

In the window of a nearby electrical shop, all the lights went out.

‘Ar,’ said Gomer dismally.

Through the hole-in-its-silencer roar of Eirion’s departing car came the sound of the phone. Jane danced into Mum’s grim scullery-office.

The light in here was meagre and cold, and a leafless climbing rose scraped at the small window like fingernails. But Jane was smiling, warm and light inside and, like, up there. Up there with the broken weathercock on the church steeple.

She had to sit down, a quivering in her chest. She remembered a tarot reader, called Angela, who had said to her, You will have two serious lovers before the age of twenty.

As she put out a hand for the phone, it stopped ringing. If Mum had gone out, why wasn’t the answering machine on? Where was Mum? Jane switched on the desk lamp, to reveal a paperback New Testament beside a newspaper cutting about the rural drug trade. The sermon pad had scribbles and blobs and desperate doodles. But there was no note for her.

Jane shrugged then sat at the desk and conjured up Eirion. Who wasn’t conventionally good-looking. Well, actually, he wasn’t good-looking at all, in some lights, and kind of stocky. And yet... OK, it was the smile. You could get away with a lot if you had a good smile, but it was important to ration it. Bring it out too often and it became like totally inane and after a while it stopped reaching the eyes, which showed insincerity. Jane sat and replayed Eirion’s smile in slow motion; it was a good one, it always started in the eyes.

Eirion? The name remained a problem. Basically, too much like Irene. Didn’t the Welsh have some totally stupid names for men? Dilwyn – that was another. Welsh women’s names, on the other hand, were cool: Angharad, Sian, Rhiannon.

He was certainly trying hard, though. Like, no way had he ‘just happened to be passing’ Jane’s school at chucking-out time. He’d obviously slipped away early from the Cathedral School in Hereford – through some kind of upper-sixth privilege – and raced his ancient heap nine or ten miles to Moorfield High before the buses got in. Claiming he’d had to deliver an aunt’s birthday present, and Ledwardine was on his way home. Total bullshit.

And the journey to Ledwardine... Eirion had really spun that out. Having to go slow, he said, because he didn’t want the hole in his exhaust to get any bigger. In the end, the bus would’ve been quicker.

But then, as Jane was climbing out of his car outside the vicarage, he’d mumbled, ‘Maybe I could call you sometime?’

Which, OK, Jane Austen could have scripted better.

‘Yeah, OK,’ she’d said, cool, understated. Managing to control the burgeoning grin until she’d made it almost to the side door of the vicarage and Eirion was driving away on his manky silencer.

The phone went again. Mum? Had to be. Jane grabbed at it.

‘Ledwardine Vicarage, how may we help you? If you wish to book a wedding, press three. To pledge a ten-thousand-pound donation to the steeple fund, press six.’

‘Is that the Reverend Watkins?’

Woman’s voice, and not local. Not Sophie at the office. And not Mum being smart. Uh-oh.

‘I’m afraid she’s not available right now,’ Jane said. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘When will she be available?’

The woman sounding a touch querulous, but nothing threatening: there was this deadly MOR computer music in the background, plus non-ecclesiastical office noise. Ten to one, some time-wasting double-glazing crap, or maybe the Church Times looking for next week’s Page Three Clerical Temptress for dirty old canons to pin up in their vestries.

‘I should try her secretary at the Bishpal tomorrow,’ Jane said.

‘I’m sorry?’

‘The Bishop’s Palace, in Hereford. If you ask for Sophie Hill...’

Most of the time it was a question of protecting Mum from herself. If you were a male vicar you could safely do lofty and remote – part of the tradition. But an uncooperative female priest was considered a snotty bitch.

‘Look.’ A bit ratty now. ‘It is important.’

‘Also important she doesn’t die of some stress-related condition. I mean, like, important for me. Don’t imagine you’d have to go off and live with your right-wing grandmother in Cheltenham. Who are you, anyway?’

Could almost hear the woman counting one... two... three... through gritted teeth.

‘My name’s Tania Beauman, from the Livenight television programme in Birmingham.’

Oh, hey! ‘Seriously?’

‘Seriously,’ Tania Beauman said grimly.

Jane was, like, horribly impressed. Jane had seen Livenight four times. Livenight was such total crap and below the intelligence threshold of a cockroach, but compulsive viewing, oh yeah.

‘Livenight?’ Jane said.

‘Correct.’

‘Where you have the wife in the middle and the husband on one side and the toyboy lover on the other, and about three minutes to midnight one finally gets stirred up enough to call the other one a motherfucker, and then fights are breaking out in the audience, and the presenter looks really shocked although you know he’s secretly delighted because it’ll all be in the Sun again. That Livenight?’

‘Yes,’ Tania said tightly.

‘You want her on the programme?’

‘Yes, and as it involves next week’s programme we don’t have an awful lot of time to play with. Is she in?’

‘No, but I’m Merrily Watkins’s personal assistant, and I have to warn you she doesn’t like to talk about the other stuff. Which is what this is about, right? The Rev. Spooky Watkins, from Deliverance?’

Tania didn’t reply.

‘I could do it, of course, if the money was OK. I know all her secrets. I’d be very good, and controversial. I’ll call anyone a motherfucker.’

‘Thank you very much,’ Tania said drily. ‘We will bear you in mind, when you turn twelve.’

‘I’m sixteen!’

‘Just tell her I called. Have a good night.’

Jane grinned. That was all Eirion’s fault. Making her feel cool.

In the silence of the scullery, the phone went again.

‘Jane?’

‘Mum. Hey, guess wh—’

‘Listen, flower,’ Mum said, ‘I’ve got bad news.’

3

Loved Like That

‘SO, LIKE... HOW long will you be?’

‘I just don’t know, flower. We came here in Gomer’s Land Rover. It was all a bit of a rush.’

‘She was never ill, was she?’ Jane said. ‘Like really never.’ The kid’s voice was suddenly high and hoarse. ‘You can’t count on anything, can you? Not even you.’

Merrily sighed. Everybody thought she could pull strings. Gomer and Minnie’s bungalow had become like the kid’s second home in the village, Minnie the closest she’d ever had to an adopted granny.

‘Flower, I’ll have to go. I’m on the pay phone in the corridor, and I’ve no more change. As soon as I get to know something...’

‘She’s not even all that old. I mean, sixty-something... what’s that? Nobody these days—’

Jane broke off. Remembering, perhaps, how young her own father had been when his life was sliced off on the motorway that night. But that was different. His girlfriend was in the car, too, and the hand of fate was involved there, in Jane’s view.

‘Minnie’s strong. She’ll fight it,’ Merrily said.

‘She isn’t going to win, though, is she? I can tell by your voice. Where’s Gomer?’

‘Gone back in, to be with her.’

‘How’s he taking it?’

‘Well, you know Gomer. You wouldn’t want him prowling around in your sickroom.’

Gomer, in retirement, groomed the churchyard, cleared the ditches, looked out for Merrily when Uncle Ted was doing devious, senior-churchwarden things behind her back. And dreamed of the old days – the great, rampaging days of Gomer Parry Plant Hire.

‘He’ll just smash the place up or something, if they let her die,’ Jane concurred bleakly.

Meaning she herself would like to smash something up, possibly the church.

How many hours had they been here? Hospitals engendered their own time zones. Merrily hung up the phone and turned back into the ill-lit passage, teeming now: visiting hours. Once, she’d had a dream of purgatory, and it was like a big hospital, a brightly lit Brueghel kind of hospital, with all the punters helpless in operation gowns, and the staff scurrying around, feeding a central cauldron steaming with fear.

‘Merrily?’

From a trio of nurses, one detached herself and came across.

‘Eileen? I thought you were over at the other place.’

‘You get moved around. We’ll all end up in one place, anyway, if they ever finish building it, and won’t that be a fockin’ treat?’ Eileen Cullen put out a forefinger, lifted Merrily’s hair from her shoulder. ‘You’re not wearing your collar, Reverend. You finally dump the Auld Feller, or what?’

‘We’re still together,’ Merrily said. ‘And it’s still hot.’

‘Jesus, that’s disgusting.’

‘Actually, I had to leave home in a hurry.’ Merrily spotted Gomer coming out of the ward, biting on an unlit cigarette, for comfort. ‘I came with a friend. His wife’s had a serious heart attack – unexpected. You won’t say anything cynical, will you?’

‘What’s his name?’ Sister Cullen was crop-haired and angular and claimed to have left Ulster to escape from ‘bloody religion’.

‘Gomer. Gomer Parry.’

‘Well then, Mr Parry,’ Cullen said briskly as Gomer came up, blinking dazedly behind his bottle glasses, ‘you look to me to be in need of a cuppa – with a drop of something in there to take away the taste of machine tea, am I right?’ She beckoned one of the nurses over. ‘Kirsty, would you take Mr Parry to my office and make him a special tea? Stuff’s in my desk, bottom drawer.’

Gomer glanced at Merrily. She moved to follow him, but Cullen put out a restraining hand. ‘Not for you, Reverend. You’ve got your God to keep your spirits up. Spare me a minute?’

‘A minute?’

‘Pity you’re out of the uniform... still, it’s the inherent holiness that counts. All it is, we’ve got a poor feller in a state of some distress, and it’ll take more than special tea to cope with him, you know what I’m saying.’

Merrily frowned, thinking, inevitably, of the first time she’d met Eileen Cullen, across town at Hereford General, which used to be a lunatic asylum and for one night had seemed in danger of reverting back.

‘Ah no,’ said Cullen, ‘you only get one of those in a lifetime. This isn’t even a patient. More like your man, Gomer, here – with the wife. And I don’t know what side of the fence he’s on, but I’d say he’s very much a religious feller and would benefit from spiritual support.’

‘For an atheist, you’ve got a lot of faith in priests.’

‘No, I’ve got faith in women priests, which is not much at all to do with them being priests.’

‘What would you have done if I hadn’t been here?’

Cullen put her hands on her narrow hips. ‘Well, y’are here, love, so where’s the point in debating that one?’

The corridor had cracked walls and dim economy lighting.

‘I’d be truly happy about leaving this dump behind,’ Cullen said, ‘if I didn’t feel sure the bloody suits were building us a whole new nightmare.’

‘What’s his name, this bloke?’

‘Mr Weal.’

‘First name?’

‘We don’t know. He’s not a man who’s particularly forthcoming.’

‘Terrific. He seen Paul Hutton?’ The hospital chaplain.

‘Maybe.’ Cullen shrugged. ‘I don’t know. But you’re on the spot and he isn’t. What I thought was... you could perhaps say a prayer or two. He’s Welsh, by the way.’

‘What’s that got to do with the price of eggs?’

‘Well, he might be Chapel or something. They’ve got their own ways. You’ll need to play it by ear on that.’

‘You mean in case he refuses to speak to me in English?’

‘Not Welsh like that. He’s from Radnorshire. About half a mile over the border, if that.’

‘Gosh. Almost normal, then.’

‘Hmm.’ Cullen smiled. Merrily followed her into a better lit area with compact, four-bed wards on either side, mainly elderly women in them. A small boy shuffled in a doorway, looking bored and aggressively crunching crisps.

‘So what’s the matter with Mrs Weal?’

‘Stroke.’

‘Bad one?’

‘You might say that. Oh, and when you’ve said a wee prayer with him you could take him for a coffee.’

‘Eileen—’

‘It’s surely the Christian thing to do,’ Cullen said lightly.

They came to the end of the passage, where there was a closed door on their right. Cullen pushed it open and stepped back. She didn’t come in with Merrily.

She was out of there fast, pulling the door shut behind her. She leaned against the partition wall. Her lips made the words, nothing audible came out.

She’s dead.

Cullen shrugged. ‘Seen one before, have you not?’

‘You could’ve explained.’

‘Could’ve sworn I did. Sorry.’

‘And the rest of it?’

‘Ah.’

‘Quite.’ What she’d seen replayed itself in blurred images, like a robbery captured on a security video: the bedclothes turned down, the white cotton nightdress slipped from the shoulders of the corpse. The man beside the bed, leaning over his wife – heavy like a bear, some ungainly predator. He hadn’t turned around as Merrily entered, nor when she backed out.

She moved quickly to shake off the shock, pulling Eileen Cullen a few yards down the passage. ‘What in God’s name was he doing?’

‘Ah, well,’ Cullen said. ‘Would he have been cleaning her up, now?’

‘On account of the NHS can’t afford to pay people to take care of that sort of thing any more?’

Cullen tutted on seeing a tea trolley abandoned in the middle of the corridor.

‘Yes?’ Merrily said.

Cullen pushed the trolley tidily against a wall.

‘There now,’ she said. ‘Well, the situation, Merrily, is that he’s been doing that kind of thing for her ever since she came in, three days ago. Wouldn’t let anyone else attend to her if he was around – and he’s been around most of the time. He asks for a bowl and a cloth and he washes her. Very tenderly. Reverently, you might say.’

‘I saw.’

‘And then he’ll wash himself: his face, his hands, in the same water. It looked awful touching at first. He’d also insist on trying to feed her, when it was still thought she might eat. And he’d be feeding himself the same food, like you do with babies, to encourage her.’

‘How long’s she been dead?’

‘Half an hour, give or take. She was a bit young for a stroke, plainly, and he naturally couldn’t come to terms with that. At his age, he was probably convinced she’d outlive him by a fair margin. But there you go: overattentive, overpossessive, what you will. And now maybe he can’t accept she’s actually dead.’

‘I dunno. It looked... ritualistic almost, like an act of worship. Or did I imagine that?’ Merrily instinctively felt in her bag for her cigarettes before remembering where she was. ‘Eileen, what do you want to happen here?’

Cullen folded her arms. ‘Well, on the practical side...’

‘Which is all you’re concerned about, naturally.’

‘Absolutely. On the practical side, goes without saying we need the bed. So we need to get her down to the mortuary soon, and that means persuading your man out of there first. He’d stay with her all night, if we let him. The other night an auxiliary came in and found him lying right there on the floor beside the bed, fast asleep in his overcoat, for heaven’s sake.’

‘God.’ Merrily pushed her hands deep down into the pockets of Jane’s duffel. ‘To be loved like that.’ Not altogether sure what she meant.

Cullen sniffed. ‘So you’ll go back in and talk to him? Mumble a wee prayer or two? Apply a touch of Christian tenderness? And then – employing the tact and humanity for which you’re renowned, and which we’re not gonna have time for – just get him the fock out of there, yeah?’

‘I don’t know. If it’s all helping him deal with his grief...’

‘You’re wimping out, right? Fair enough, no problem.’

Merrily put down her bag on the trolley. ‘Just keep an eye on that.’

Well, she didn’t know too much about rigor mortis, but she thought that soon it wouldn’t be very easy to do what was so obviously needed.

‘We should close her eyes,’ Merrily said, ‘don’t you think?’

She put out a hesitant hand towards Mrs Weal, thumb and forefinger spread. The times she’d done this before were always in the moments right after death, when there was still that light-smoke sense of a departing spirit. But, oh God, what if the woman’s eyelids were frozen fast?

‘You will,’ Mr Weal said slowly, ‘leave her alone.’

Merrily froze. He was standing sentry-stiff. A very big man in every physical sense. His face was broad, and he had a ridged Roman nose and big cheeks, reddened by broken veins – a farmer’s face. His greying hair was strong and pushed back stiffly.

Without looking at her, he said, ‘What is your purpose in being here, madam?’

‘My name’s Merrily.’ She let her hand fall to her side. ‘I’m the... vicar of Ledwardine.’

‘So?’

‘I was just... I happened to be in the building, and the ward sister asked me to look in. She thought you might like to... talk.’

Could be a stupid thing to say. If there ever was a man who didn’t like to talk, this was possibly him. Between them, his wife’s eyes gazed nowhere, not even into the beyond. They were filmed over, colourless as the water in the metal bowl on the bedside table, and they seemed the stillest part of her. He’d pulled the bedclothes back up, so that only her face was on show. She looked young enough to be his daughter. She had light brown hair, and she was pretty. Merrily imagined him out on his tractor, thinking of her waiting for him at home. Wife number two, probably, a prize.

‘Mr Weal – look, I’m sorry I don’t know your first name...’

His eyes were downcast to the body. He wore a green suit of hairy, heavy tweed. ‘Mister,’ he said quietly.

‘Oh.’ She stepped away from the bed. ‘Right. Well, I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to upset you... any further.’

There was a long silence. The water bowl made her think of a font, of last rites, a baptism of the dying. Then he squinted at her across the corpse. He blinked once – which seemed, curiously, to release tension, and he grunted.

‘J.W. Weal, my name.’

She nodded. It had obviously been a mistake to introduce herself just as Merrily, like some saleswoman cold-calling.

‘How long had you been married, Mr Weal?’

Again, he didn’t reply at once, as though he was carefully turning over her question to see if a subtext dropped out.

‘Nine years, near enough.’ Yerrs, he said. His voice was higher than you’d expect, given the size of him, and brushed soft.

Merrily said, ‘We... never know what’s going to come, do we?’

She looked down at Mrs Weal, whose face was somehow unrelaxed. Or maybe Merrily was transferring her own agitation to the dead woman. Who was perhaps her own age, mid to late thirties? Maybe a little older.

‘She’s... very pretty, Mr Weal.’

‘Why wouldn’t she be?’

Dull light had awoken in his eyes, like hot ashes raked over. People probably had been talking – J.W. Weal getting himself an attractive young wife like that. Merrily wondered if there were grown-up children from some first Mrs Weal, a certain sourness in the hills.

She swallowed. ‘Do you, er... belong to a particular church?’ Cullen was right; he looked like the kind of man who would do, if only out of tradition and a sense of rural protocol.

Mr Weal straightened up. She reckoned he must be close to six and a half feet tall, and built like a great stone barn. His eyebrows met, forming a stone-grey lintel.

‘That, I think, is my personal business, thank you.’

‘Right. Well...’ She cleared her throat. ‘Would you mind if I prayed for her? Perhaps we could—’

Pray together, she was about to say. But Mr Weal stopped her without raising his voice which, despite its pitch, had the even texture of authority.

‘I shall pray for her.’

Merrily nodded, feeling limp. This was useless. There was no more she could say, nothing she could do here that Eileen Cullen couldn’t do better.

‘Well, I’m very sorry for the intrusion.’

He didn’t react – just looked at his wife. For him, there was already nobody else in the room. Merrily nodded and bit her lip, and walked quietly out, badly needing a cigarette.

‘No?’ Eileen Cullen levered herself from the wall.

‘Hopeless.’

Cullen led her up the corridor, well away from the door. ‘I’d hoped to have him away before Menna’s sister got here. I’m not in the best mood tonight for mopping up after tears and recriminations.’

‘Sorry... whose sister?’

‘Menna’s – Mrs Weal’s. The sister’s Mrs Buckingham and she’s from down south and a retired teacher, and there’s no arguing with her. And no love lost between her and that man in there.’

‘Oh.’

‘Don’t ask. I don’t know. I don’t want to know.’

‘What was Menna like?’

‘I don’t know. Except for what I hear. She wasn’t doing much chatting when they brought her in. But even if she’d been capable of speech, I doubt you’d have got much out of her. Lived in the sticks the whole of her life, looking after the ole father like a dutiful child’s supposed to when her older and wiser sister’s fled the coop. Father dies, she marries an obvious father figure. Sad story but not so unusual in a rural area.’

‘Where’s this exactly?’

‘I forget. The Welsh side of Kington. Sheep-shagging country.’

‘Charming.’

‘They have their own ways and they keep closed up.’

The amiable, voluble Gomer Parry, of course, was originally from the Radnor Valley. But this was no time to debate the pitfalls of ethnic stereotyping.

‘How did she come to have a stroke? Do you know?’

‘You’re not on the Pill yourself, Merrily?’

‘Er... no.’

‘That would be my first thought with Menna. Still on the Pill at thirty-nine. It does happen. Her doctor should’ve warned her.’

‘Wouldn’t Mr Weal have known the dangers?’

‘He look like he would?’ Cullen handed Merrily her bag. ‘Thanks for trying – you did your best. Don’t go having nightmares. He’s just a poor feller loved his wife to excess.’

‘I’ll tell you one thing,’ Merrily said. ‘I think he’s going to need help getting his life back on track. That’s the kind of guy who goes back to his farm and hangs himself in the barn.’

‘If he had a barn.’

‘I thought he was a farmer.’

‘I don’t think I said that, did I?’

‘What’s he do, then? Not a copper?’

‘Built like one, sure. No, he’s a lawyer, as it happens. Listen, I’m gonna have a porter come up and we’ll do it the hard way.’

‘A solicitor?’

Cullen gave her a shrewd look. She knew Sean had been a lawyer, that Merrily herself had been studying the law until the untimely advent of Jane had pushed her out of university with no qualifications. The difficult years, pre-ordination.

‘Man’s not used to being argued with outside of a courthouse,’ Cullen said. ‘You go back and find your wee friend. We’ll sort this now.’

Walking back towards Intensive Care, shouldering her bag, she encountered Gomer Parry smoking under a red No Smoking sign in the main corridor. He probably hadn’t even noticed it. He slouched towards her, hands in his pockets, ciggy winking between his teeth like a distant stop-light.

‘Sorry about that, Gomer. I was—’

‘May’s well get off home, vicar. Keepin’ you up all night.’

‘Don’t be daft. I’ll stay as long as you stay.’

‘Ar, well, no point, see,’ Gomer said. He looked small and beaten hollow. ‘No point now.’

The scene froze.

‘Oh God.’

She’d left him barely half an hour to go off on a futile errand which she wasn’t up to handling, and in her absence...

In the scruffy silence of the hospital corridor, she thought she heard Minnie Parry at her most comfortably Brummy: Yow don’t go worrying about us, my duck. We’re retired, got all the time in the world to worry about ourselves.

Instinctively she unslung her bag, plunged a hand in. But Gomer was there first.

‘Have one o’ mine, vicar. Extra-high tar, see.’

4

Repaganization

TUESDAY BEGAN WITH a brown fog over the windows like dirty lace curtains. The house was too quiet. They ought to get a dog. Two dogs, Robin had said after breakfast, before going off for a walk on his own.

He’d end up, inevitably, at the church, just to satisfy himself it hadn’t disappeared in the mist. He would walk all around the ruins, and the ruins would look spectacularly eerie and Robin would think, Yes!

From the kitchen window, Betty watched him cross the yard between dank and oily puddles, then let himself into the old barn, where they’d stowed the oak box. Robin also thought it was seriously cool having a barn of your own. Hey! How about I stash this in... the barn?

When she was sure he wouldn’t be coming back for a while, Betty brought out, from the bottom shelf of the dampest kitchen cupboard, the secret copy she’d managed to make of that awful witch charm. She’d done this on Robin’s photocopier while he’d gone for a tour of Old Hindwell with George and Vivvie, their weekend visitors who – for several reasons – she could have done without.

Betty now took the copy over to the window sill. Produced in high contrast, for definition, it looked even more obscurely threatening than the original.

First the flash-vision of the praying man in the church, then this.

O Lord, Jesus Christ Saviour Salvator I beseech the salvation of all who dwell within from witchcraft and from the power of all evil... Amen Amen Amen... Dei nunce... Amen Amen Amen Amen Amen.

Ritualistic repetition. A curious mixture of Catholic and Anglican. And also:

By Jehovah, Jehovah and by the Ineffable Names 17317... Holy Names... Elohim... Emmanuel...

Jewish mysticism... the Kabbalah. A strong hint of ritual magic. And then those symbols – planetary, Betty thought, astrological.

It was bizarre and muddled, a nineteenth-century cobbling together of Christianity and the occult. And it seemed utterly genuine.

It was someone saying: We know about you. We know what you are.

And we know how to deal with you.

Inside the barn, the mysterious box was still there, tucked down the side of a manger. All the hassle it was causing with Betty, Robin had been kind of hoping the Local People would somehow have spirited this item away again. It was cute, it was weird but it was, essentially, a crock of shit. A joke, right?

The Local People? He’d found he was beginning to think of ‘the local people’ the way the Irish thought of ‘the little people’: shadowy, mischievous, will-o’-the-wispish. A different species.

Robin had established that the box did originally come from this house. Or, at least, there were signs of an old hiding place inside the living-room inglenook – new cement, where a brick had been replaced. So was this the reason Betty had resisted the consecration of their living room as a temple? Because it was there that the anti-witchcraft charm had been secreted?

Betty’s behaviour had been altogether difficult most of the weekend. George Webster and his lady, the volatile Vivvie, Craft-buddies from Manchester, had come down on Saturday to help the Thorogoods get the place together, and hadn’t left until Monday afternoon. It ought to have been a good weekend, with loud music, wine and the biggest fires you could make out of resinous green pine. But Betty had kept on complaining of headaches and tiredness.

Which wasn’t like her at all. As a celebratory climax, Robin had wanted the four of them to gather at the top of the tower on Sunday night to welcome the new moon. But – wouldn’t you know? – it was overcast, cold and raining. And Betty had kept on and on about safety. Like, would that old platform support as many as four people? What did she think, that he was planning an orgy?

Standing by the barn door, Robin could just about see the top of the tower, atmospherically wreathed in fog. One day soon, he would produce a painting of it in blurry watercolour, style of Turner, and mail it to his folks in New York. This is a sketch of the church. Did I mention the ancient church we have out back?

And ancient was right.

This was the real thing. The wedge of land overlooking the creek, the glorious plot on which the medieval church of St Michael at Old Hindwell had been built by the goddamn Christians, was most definitely an ancient pagan sacred site. George Webster had confirmed it. And George had expertise in this subject.

Just take a look at these yew trees, Robin, still roughly forming a circle. That one and that one... could be well over a thousand years old.