2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

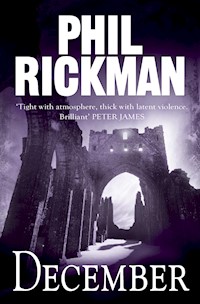

A standalone supernatural thriller from the author of the chilling Merrily Watkins Mysteries. December has the shortest days, the darkest nights... In the ruins of a medieval abbey on the Welsh Border, four young musicians start work on an album influenced by the site's bloody history. It's December 1980 - the night John Lennon will be murdered in New York. And there'll be more horror before the sun rises and the session tapes are burned. Or are they? Years later, Moira, Dave, Tom and Simon are persuaded to return to the abbey to complete the recordings they thought had been destroyed. But the old tapes - and all the darkness they contain - have been restored. And it's December again. A PHIL RICKMAN STANDALONE NOVEL

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

December

PHIL RICKMAN was born in Lancashire and lives on the Welsh border. He is the author of the Merrily Watkins series, and The Bones of Avalon. He has won awards for his TV and radio journalism and writes and presents the book programme Phil the Shelf for BBC Radio Wales.

ALSO BY

PHIL RICKMAN

THE MERRILY WATKINS SERIES

The Wine of Angels Midwinter of the Spirit A Crown of Lights The Cure of Souls The Lamp of the Wicked The Prayer of the Night Shepherd The Smile of a Ghost The Remains of an Altar The Fabric of Sin To Dream of the Dead The Secrets of Pain

THE JOHN DEE PAPERS

The Bones of Avalon

OTHER TITLES

Candlenight Curfew The Man in the MossDecember The Chalice

PHIL RICKMAN

December

First published 1994 by Macmillan

This edition first published in Great Britain in 2011 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Phil Rickman, 1994

The moral right of Phil Rickman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. All characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-8578-9690-2 Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26-27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZwww.corvus-books.co.uk

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

I Cemented in Blood

II Electric Grief

Part One

I Darkness at the Break of …

II The Next Big Thing

III The Hideous Bonnet

IV Profanity from a Man of the Cloth

V A Sighing of Satin

Part Two

I A Sob You Could See

II Baking

III All Dead

IV Protection of the Ancestors

V A Moth in Winter

VI Dead Sea Scroll

VII Delphinium Blue

VIII Predator

IX Allergy Syndrome

X The Man With Two Mouths

XI Bloody Glasses

XII Reassurance for the Living

XIII Dakota Blues

XIV Keys

XV Bunny

XVI Plop, Plop, Plop

Part Three

I Dreamer

II A Rebel and a Bastard

III Can This Bastard See My Aura?

IV End of Story

V Curse of the Witchy Woman

VI Like a Dog Turd

VII December: Ain’t It Always?

VIII Spiritual Haven Garbage

IX Like Chicken Bones

X Monkscock

XI Flying

XII Heart of Nowhere

Part Four

I Old Love

II Orphan

III Supernatural Junkie

IV Whatever Gets You Through the Night

V Cortège

VI Ferret

VII Gin Trap

VIII Dream Made Flesh

IX AA

X Organism

XI Bart Simpson

XII Darker Underneath

Part Five

I Spirit

II Unhappy Ghosts

III Bluefoot

IV Crucifixion

V The Abbey’s Children

VI Home at Last

VII Stricken Angel

VIII The Big Taunt

IX Blues

Epilogue

Closing Credits

December

I

Cemented in Blood

DECEMBER 8, 1980

By the time he makes the doorman’s office, his glasses have come off, and blood and tissue and stuff are emptying urgently from his mouth.

He falls.

He lies in the blood on the office floor, and he doesn’t move. A short while later, two cops are turning him over, real careful, and seeing the blood around the holes – four holes, maybe five. And then they’re carrying him, bloody face up, out to the patrol car, leaving behind these puddles and blotches on the doorman’s floor.

Normal way of things, these cops wouldn’t move a man in such poor condition. The state of this one, it’s clear there’s going to be no premium in hanging around for an ambulance.

‘This guy is dying,’ one cop says.

When they raised him up, the doorman thought he heard a sound like the snapping of bones.

It’s just after eleven p.m.

Somewhere out there in the night, Dave hears what he thinks is the snapping of twigs. And the twigs are talking, crackling out words.

death oak,

Say the twigs.

Dave’s under the swollen branches of some old tree. Not an oak tree. But twigs in the copse are crackling the words, and they come as this weird rasp on the night wind, and he hears the echo of a barn owl across the valley, and the owl – he’d swear – is screeching,

death oak.

*

Between the shadowy mesh of bare branches and broken stone arches, Dave can see the lights inside the Abbey.

The Abbey is old and ruinous. A glowering heap of twelfth-century stone, which by day is the raw, wind-soured pink of an old farmer’s skin. By night – like now – it’s mainly black, a jagged and knobbly rearing thing among the wooded border hills flanking the Skirrid, the holy mountain of Gwent. Legend says the Skirrid was pulled apart by a massive seismic shudder at the very moment of Christ’s crucifixion.

The shudders inside Dave tonight are not exactly seismic. But he wouldn’t deny, standing trembling under the dripping tree, that he’s coming apart.

In a corner of the ruins, incongruous as a heart inside a skeleton, is a stone tower built over the vaults where the monks stored wine imported from France. The studio’s down here now, built into the vaults. A romantic, evocative place to record music. In the daytime. In summer. Maybe.

At night, in winter, forget it.

Tonight, nervy lights were wobbling behind pimply, leaded glass as Dave spun away from the Abbey, hurling himself, sobbing, at the trees, his canvas shoes skidding on the winter-wet lawn. Clamping his hands over his ears, vibrating them as if he could somehow shake the phrase – death oak – out of his skull.

I can handle it, I can direct it, I can …

Ah, but you know you really can’t.

See, the problem is, if you’re in some way … sensitive, then people – the ones who don’t think you’re a phoney, or misguided or totally out of your tree – have this curious idea that you must be spiritually advanced. Serene. In control.

This means not running away.

Well, it’s fine for them to talk, the ones who think it’s a beautiful gift. They should be here tonight in this holy place.

And we, Dave thinks, should have listened to Tom Storey.

*

‘What the fuck is this?’

Big Tom from Bermondsey, lead guitar, fearless on the frets, was wedged into the narrow, arched doorway at the top of the steps, roaring at everybody. Some of it was outrage. Most of it, Dave could tell, was panic.

In the studio, the churchy light, wavering.

About a dozen lighted candles in metal holders, brass and wooden candlesticks and saucers were spread out, apparently at random, around the whitewashed vault.

In the recording booths, candles burned. Little white snow-drop lights glimmered from ledges and amps. Melted wax was oozing down Lee Gibson’s middle cymbal.

No other light than this. Looked quite cosy, Dave thought irrationally. A touch Christmassy.

And then he thought, No, it could be cosy. Somewhere else. Almost anywhere else. Anywhere but the Abbey of Ystrad Ddu, where it was said that every stone in the walls had been cemented with blood.

He’d followed Lee, Moira and Simon into the studio, and Moira had stopped at the bottom of the steps and said quietly, ‘I don’t like this.’ And now Tom wouldn’t come through the door.

Dave looked at Moira and mouthed a word: joke?

‘Well, I’m no’ laughing,’ Moira said out of the side of her mouth.

She was young and moon-pale, wearing a long dark velvet dress and a lustrous silver headband and glowing far brighter, for Dave, than the candles.

‘OK.’ Simon St John strolled languidly into the centre of the studio. ‘If whoever did this is listening from anywhere, we’re all suitably terrified, aren’t we, Dave?’

‘Er … yeh. Right. Crapping ourselves.’ Dave looked at Simon and Simon raised an eyebrow, probably signalling that Dave should remember tonight’s motto, which was, Don’t Worry Tom.

Dave nodded.

‘Come on down, Tom. Come on.’ Simon sounding as if he was calling a dog. ‘Nothing to worry about, squire. Nothing sinister. Somebody taking the piss, that’s all.’

Simon, smooth and willowy, had credibility. While it was acknowledged that Tom was the best musician, he was still a rock musician. Whereas Simon was, er, classically trained, actually. Plus, he was public-school educated, a laid-back, well-spoken guy, a calming influence. Serene? Did a good impression, anyway.

Tom looked nervously from side to side, like he was on the edge of a fast road, and then came down, making straight for the metal stand where his solid-bodied Telecaster guitar sat. He snatched up the Telecaster and strapped it on, like armour. He was tense as hell.

‘Joke, right?’ The brash young session drummer, Lee Gibson, had followed Tom down the steps. Lee was not a full member of the band, lacking the essential qualifications – i.e. he was too close to normal.

Dave began to count the candles, becoming aware of this rich, fatty smell. The candles had been burning a while and dripping. Christmas was wrong; the studio looked like a chapel of rest awaiting a body. Except in a chapel of rest, the candles wouldn’t be …

‘Black!’ Tom let out this hoarse yelp, flattening himself instinctively against a wall. ‘Fucking things are black! You call that a bleeding joke?’

Dave finished counting. Thirteen. Oh hell.

‘Hey, come on, candles can be protective, too,’ Moira said uncertainly.

‘Bullshit.’ The wavy light was kinder to Moira than to Tom. His eyes were puffy, heavy moustache spread across his mouth like a squashed hedgehog. ‘Bullshit!’ Clamping his Telecaster to his gut, its neck angled on a couple of candles like a rifle.

The flames of the two candles, dripping on to adjacent amps, seemed to flare mockingly.

‘Brown,’ Lee Gibson said. ‘They’re only dark brown, see?’

Dave peered at one. It looked black enough to him, and it smelled like a butcher’s shop in August. Also – and this wasn’t obvious because several were concealed by the partitions around individual booths – if you stood in the centre of the studio floor, you could see the candles had been arranged in almost a perfect circle. If this was a wind-up, somebody had gone to a lot of trouble.

Be totally pointless organizing a witch-hunt. This was a residential recording studio, people coming and going, silent, discreet, like the medieval monks who’d built the Abbey.

‘Fuck’s sake, man, they only look black.’ Lee had on leather trousers and a moleskin waistcoat over his bare chest, a guy already shaping his own legend. Clearly anxious to get started; this session would be crucial to his career-projection.

Tom regarded him with contempt. ‘Thank you, son.’ A warning rumble Dave had heard before; he tensed. ‘That makes me feel so much better,’ Tom said. And then spasmed.

‘Hey, man …’ Lee reeling back ‘… fuck’s sake!’ as Tom swung round, his guitar neck sweeping a candle from an amplifier stack. It spun in the air before dropping into a heap of lyric sheets on the floor. Cold flames spurted.

Nobody spoke. Simon walked over and calmly stamped on the papers. Meanwhile Russell Hornby, the producer, had slid noiselessly into the studio.

‘OK, guys. Let’s become calm, shall we?’ Russell was slight and bald. He wore dark glasses, even at night.

‘Russell,’ Tom snarled, ‘this is the end of the line, my son. We are packing up. You are getting us out. We have taken enough of this shit.’

‘Excuse me,’ Russell said blandly, ‘but surely this “shit” is part of the object of the exercise, isn’t it?’

‘Hang on.’ Dave picked up one of the candles. It felt nasty, greasy, like a fatty bone. ‘Are you saying you did this, Russell? These are your candles?’

‘Dave, you think I’d cut my own throat? Nor, before you ask, do I know who’s responsible for the blasted lightbulbs bursting last night. Nor the apparent blood on the dinner plates. Nor even your inability, Dave, to keep a guitar tuned for five minutes.’

He snatched the candle from Dave and blew at it. The candle stayed alight. Russell threw it to the stone floor and crushed it with his heel. ‘Now, what I suggest is we get rid of them before we’re in breach of fire regulations, yeah? And then let’s go to work.’

This guy was well chosen, Dave thought. If you were putting four musicians with special qualities – one of Russell’s slightly sneering phrases – into a situation as potentially volatile as this, you needed a producer who was calm, efficient, businesslike and about as sensitive as a shower-attendant at Auschwitz.

‘Look,’ Russell said reasonably. ‘Let’s not overreact. It’s been a difficult week …’

‘ “Difficult”,’ Dave said. ‘That’s a good word, Russell.’

‘… But I take it none of us wants to have to start all over again, yeah? So I suggest we bolt the doors against any marauding ghouls, restless spirits and whatever the word is for those things alleged to move the furniture around … and give me something I can mix.’

‘I’ll give you something you can fucking mix …’ Tom advanced on Russell, his face pulsing electrically in the unsteady candlelight.

‘Stop it!’ Moira had marched between them and stamped her foot. ‘Tom, you’re taking this far too seriously. And Russell, you’re not taking us seriously enough. Nobody’s asking you to believe in the paranormal, just don’t be so damn superior and contemptuous of people who do, OK?’

Oh God, Dave thought, I love her.

Everybody had gone quiet. ‘Yeah, well, that’s all I’ve got to say,’ Moira said. She came and stood by Dave. He felt her warm breath on his ear, essence of heathery moors sloping down to long white beaches and a grey, grey sea, and he thought he was going to pass out with the longing.

‘Come on then.’ Snapping out of it, slapping his thighs with both hands. ‘Let’s get rid of the buggers.’ Dave padded around the studio, blowing out the remaining candles, collecting them up. Afterwards his hands felt like he was wearing slimy rubber gloves. Yuk, horrible! He piled the candles into a corner, feeling slightly sick.

Someone put on the electric lights, and Russell Hornby took Tom into another corner and talked placatingly at him until, at last, the big guy shambled to his feet, his brass-studded guitar strap still over his shoulder like the bridle on a shire horse.

‘Right, then. Four hours.’ Tom jabbed a big, hard finger at Russell. ‘And then I’m out of here, no arguments.’ Tom was the only one of them staying in a hotel, to be with his wife.

He stared balefully at the rest of them before stumping off to the payphone in the passage. They heard him bawling down the phone, telling the long-suffering Deborah when to pick him up. ‘Yeah, main gate, say ’bout half four, quarter to five … Yeah, yeah … Too right.’

‘Guy’s got no consideration whatsoever,’ Moira said. ‘Eight months gone, Jesus, she needs all the sleep she can get. I mean, how’s he know what the roads are gonna be like by then?’

Dave was wishing he was driving back to a hotel ten miles away. There to lie with Moira, warm and naked in his arms and smelling of heather and salt-spray and …

He stifled a moan. It was only these little Moira fantasies that kept him sane. He watched her pick up her guitar, one of the new Ovations with a curving fibreglass body. She began to sing softly. … the doors are all barred, the candles are smothered …

Her tune, his lyric. He loved watching her soft lips shape his words, eyes downcast over the guitar, the black hair swaying like velvet curtains drawn across an open window. … and nobody wants to hear Aelwyn …

Moira’s lips had touched his own just once, in greeting – Hi, Dave, mmmmph – but a man could hope.

When Tom slouched back into the studio and grumpily shouldered his guitar, they all wandered into their booths and pushed on with it, prisoners of the small print on their contract. … this album shall be recorded exclusively and entirely at the Abbey Studios, North Gwent, between midnight and dawn.

The great experiment initiated and financed by Max Goff, founder and managing director of Epidemic Independent Records UK Ltd and student of the Unexplained, the man who maintained that: Music is the only art form that’s also a spiritual force.

Outside, the wind might have been moaning a little, although you wouldn’t know it in the sealed capsule of the studio, but it was really quite a mild night. For December.

But it was cold out on the hills, and there was snow, and he had no cloak; he could feel neither his fingers nor his toes in his worn-out boots, and the sweat froze on his face as he ran towards the distant light, a candle in a window slit.

At least the killing wind was with him. The wind blew at his back and speeded his footsteps, though he stumbled many times and knew his hands and face had been opened and the blood frozen in the wounds.

His ears always straining for the sound of other footsteps on the icy track, the clamour of men and horses … knowing the wind which speeded his flight would also speed their pursuit, these murdering, damned ewe-fuckers …

Final track, side-one, live take: ‘The Ballad of Aelwyn Bread-winner.’ In which, absorbing the subtle emanations, we retell the tragic tale of the famous medieval Celtic martyr in the very place where he was so brutally cut down by Norman soldiers in the year 1175.

Let’s get this over.

In his personal booth, hugging his Martin guitar, eyes closed, Dave was Aelwyn. But Aelwyn was alone, while Dave could hear Simon on safe, plodding bass, Tom’s low, undulating guitar. And there was Moira’s voice in his cans, soft and low and dark as Guinness. He could feel the closeness of her, closer than sex; she was in his head, she was with him on the frozen hills, as he ran from the soldiers and mercenaries, wondering if he would even feel it as they cut him down with their blades of ice. The cold from the song, the all-shrouding inevitability of imminent death, the end of everything, was around him in the booth, his bare arms tingling as he played.

When the cans went funny, Moira was playing soft, gliding, rhythm guitar and singing counterpoint – an ethereal voice, distant on the winter wind. The voice from the holy mountain guiding Aelwyn to safety.

Aelwyn had been very tired, tramping through the snow towards the Abbey. Had known they were coming for him, but simply hadn’t the strength to run any more. But he also knew that when he reached the Abbey he’d be OK. Even these bastards were not going to smash their way into the house of God, especially not this house of God, founded upon the site of a famous Holy Vision.

This was where the cans went funny. Where other voices came in, as though, as sometimes happened, a radio signal had got into the system.

She couldn’t hear what the voices were saying. She carried on playing and singing but looked out of the glass panel in the partition around the booth. Nobody came out on to the studio floor waving his hands. In the booth opposite, Dave played on. Maybe – she didn’t understand too much technical stuff – Russell and Barney, the engineer, were not picking up the extraneous voices on their tape.

So Moira played on, too.

The band had rehearsed the song several times today. She figured she was pretty much immune to the ending by now, but she’d still been feeling tension on Dave’s behalf. Dave was not what you’d call a great singer but he sure could get himself into a role. For now, for the duration of this song, Dave was Aelwyn and Aelwyn was Dave, and the last sound she’d heard before the voices intruded was his breath coming harder, and she’d felt the fatigue and the creeping sense of cold despair as Aelwyn realized he wasn’t going to make it.

But surely … he could have made it.

This strange thought came to Moira just as the lights dimmed outside the booth.

She leaned forward on her stool, still playing, and peered out through the glass. All was indistinct: tumbling shadows, the snaking flex and rubber leads were like roots and vines, the amplifier stacks like black rocks. As she watched there were three small explosions in the sky, lightbulbs blowing silently in the ceiling, like the dying of distant worlds.

Under her fingers, the guitar strings felt cold and sharp like the edges of blades. As the bulbs went out, several small, blue-white spearpoint flames flared in the middle distance.

This would be the corner where Dave had laid the candles, some still upright in trays and holders. All of them snuffed.

All of them snuffed.

Oh no …

II

Electric Grief

He saw … … a fortress: massive, dark, forbidding, ungiving – a Bastille of a place. It rose in billows, a towering mushroom of smoke, lighted windows appearing, and peaks and gables forming out of the smog. Overpowering. Dizzying. And warped, like through a fisheye lens. Like it was swaying before it toppled on to him. Or somebody.

He heard a roaring, shot through with vivid screams, like thunderclouds speared by lightning forks.

And more.

Through the glass side of his booth, he’d seen the dead candles flickering, triumphant.

Heard the voices hissing,

deathoak

Still hearing, from somewhere, Moira’s voice against the elements, but the words were inaudible, the only words he could make out were death oak suspended in the tight studio acoustic, and he was sure that if he looked hard enough, he would see the words light up, blinking in the smoky space like neon, like the cold fingernails of fire at the tips of the candles.

And he was so cold.

And then an explosion of lights and he was looking up at the fortress. Monster of a building. Bit like one of those French whatsits, châteaux. But too big to be an original and not so delicate. Overwhelming. Forbidding – kind of Victorian Gothic.

And then blackness. Deep, throbbing blackness.

And someone saying,

this guy is dying.

Outside now, clinging to the tree, Dave vaguely remembers unslinging the Martin, letting it fall, bolting out of his booth.

Still hearing it, death oak, as he rushed at the rear door, seeing Russell and his engineer, Barney, on their feet in the control room, behind the glass panel, mouths moving, no sound. Passing the booth containing Tom, hunched, red-faced, doubled up over the Telecaster, as if his appendix was bursting or something, the guitar bansheeing from the amp.

Plunging through the rear door into the stone passage, his legs weak and cold, like poor bloody Aelwyn’s. Dashing across the lawn towards the trees, for shelter.

Sanctuary.

Realizing now how perishing cold he is, slumped under the dripping tree in his T-shirt, canvas shoes soaked through. But not cold like Aelwyn and not cold like … who?

Now, out here on the edge of the wood, comes another voice, the only voice he ever wants to hear.

‘Tell me about it. Davey, for God’s sake …’

He mumbles, ‘I love you.’

‘Davey … !’

He opens his eyes, sees concern furrowing her forehead. She’s edged with gold from the lights in the house, and he’s starting to cry, just wanting to hold her and lose himself in the dark wildwood of her hair. Drunk with relief, he’s burbling through the tears, ‘Oh God, I love you, Moira, I really love you.’

‘Davey, listen, something awful bad’s going down.’

‘Can we go away together? I really do love you, Moira. Can we …?’

‘Sure. Oh, Davey, please, you have to tell me what you saw.’

‘If I tell you, can we go away?’

‘Oh Jesus, Davey,’ Moira says ruefully. ‘I think we’ll all be going away soon.’

Ten minutes later, she’s saying, ‘Where? Where was this?’

‘I couldn’t tell you. I’m sorry. How long have I been out here?’

‘An hour. Maybe more. We couldny find you. Davey, think yourself back. Come on now.’

Moira is standing on the edge of the lawn, shivering in her stupid black velvet frock, the kind of frock fortune tellers wear at the village fête. The session broken up into chaos and recriminations, Russell throwing up his hands, Lee hurling his drumsticks at the wall. Not everybody wanting even to look for Dave.

Dave says, ‘What about you?’

‘I … I can’t remember, Davey,’ Moira lies. ‘Like a bad dream after you wake up, and, like, all you recall is the atmosphere.’

Oh God, she’s thinking, why’d we agree to come here?

It was really wonderful, at first, this band. Communal therapy, sitting in a circle like an encounter group, exchanging wild tales over gallons of tea and coffee. Incredibly reassuring to know there are other people like you: Simon, kind and diffident and mixed up sexually. Tom, like so many of these guitar virtuosos, a touch unbalanced (OK, very unbalanced) but with this grumpy charm. And Davey. Soft-centred and funny, and he fancies you madly …

We were a good band. We were getting along, we really cooked musically. Because we have problems in common, a problem. Some people would say it’s a gift; some people would say a club foot’s a gift. But, as the old saying goes, a problem shared is a problem halved.

So why, in the sanctified atmosphere of the Abbey – forgetting for the moment about all this steeped in blood stuff – is a problem shared turning out to be a problem enhanced and multiplied?

Dave’s shaking his head. ‘Traffic? Lights?’

‘Traffic-lights, Davey?’

‘No, traffic – and lights. People … People shouting. Wailing. Somebody hurt, maybe.’

‘Man or a woman?’

‘Or dead. Dead, I think. I don’t know.’

‘What about the wailing? Why are they wailing? This is no’ Aelwyn, is it? I mean, this is nothing to do with …’

‘Shock.’ Shaking his head. ‘Shock and grief … kind of an – electric grief. Hundreds of people. Not wailing. Singing? But not happy. Not happy singing, y’ know?’

Moira’s eyes, adjusted to the lack of light, can see him clearly now. He’s looking awful cold, still in just his white T-shirt, sweat and mud stains on the chest. Gonna catch his death.

‘Come back to the house, Davey.’

‘Nnnn.’ Shaking his head. Assuming that whatever brought this on is back there, waiting for him, and he might not be wrong. Mumbling again, eyes squeezed shut.

‘OK, then,’ Moira says calmly. ‘Take me there.’

And he does.

‘I’m looking down on it now … down into it … it’s on all these different levels, and packed with, like, jutting, thrusting masonry … turrets, chimneys, spikes … like, if you fell into it, you’d impale yourself. You know what I …?’

Gently, she pulls his arms away from the tree, holds them, one in each hand. She can feel the goosebumps.

Dave says, ‘A cupola kind of thing, glass sides. And below me, on the ground, a black … a rigid thing with black …’

‘Petals,’ Moira says suddenly, not thinking about it. ‘It’s a flower, right?’

‘Yes. It’s a black flower.’

‘Metal?’

‘A metal flower, right. And noise, rising up. Black noise. Lights that crash. Lights that scream. Heavy lights shattering. Christ, there’s no sequence to this, it’s …’

‘I can’t hear it, Davey.’ Holding tight to his arms, the coldness coming through, but nothing else. ‘Let me in, Davey, let me help.’

But he’s pulling away from her, as if he’s been hit. Clutching at the tree, starting to slide slowly down its damp, knobbly trunk.

‘Eyes.’ Whimpering now. ‘Me eyes are full of blood.’

Moira sees a torchbeam waving back and forth across the lawn. ‘Simon? Tom? Help me, please. It’s Dave, he’s …’

This guy …

somebody says,

this guy is dying …

Really clearly. Saying it very simply, like it isn’t something you can easily believe. A man says,

do you know who you are?

For a moment he’s not sure. Darkness enfolding him, the metal petals of the black flower closing over his head. He tries to say something; his voice has gone. He tries to focus; his vision has grown grey and dim. Tries to move, but the petals are holding him. Tries to breathe. But there’s no air.

this guy is dy—

The black flower has a waxy perfume.

Do you know who you are?

And, somewhere else, very softly, ‘Davey …’

Crags and moorland and long white beaches. Grey seas and long white beaches, rocks wet

‘Davey!’

with a splash of spray. Desperately, he throws himself into the spray.

‘Dave Reilly.’ Whispering. ‘I’m Dave Reilly.’ Gripping an overhanging branch.

‘Simon, quick! Over here …’

He starts to breathe in the night, blinks. Feels the breeze. Blinks. Open his eyes as wide as they’ll go.

Blinks again, frantic now. ‘I can’t see.’ Brings a hand to his eyes in panic, keeps opening and shutting and rubbing them. ‘Me glasses. Where’s me glasses?’ Looking blindly from side to side, up towards the branches, down towards the grass, starting to sob. ‘Where’s me bloody glasses?’

Bloody glasses. An unremarkable pair of tinted glasses, misted and opaque. Rimmed with blood.

In the car, the cop says, ‘Do you know who you are?’

He can’t talk. Just moans and nods. Of course he fucking knows.

Moira says gently, ‘Davey, you don’t wear glasses.’

‘No.’ Dave, calm again, opens his eyes very, very slowly and becomes aware of a very still winter night in the Black Mountains of Gwent. A night in December, two, three weeks off Christmas. A night with no visible moon, only lights from the Abbey fifty yards away, behind huge, black, stone arches like the ribcage of a dinosaur skeleton.

The Abbey: twelfth-century stone, a crackling log fire in the panelled hall, mulled wine in pewter mugs. And in a long, black velvet dress …

‘Moira?’

‘I’m here.’

He sees her face, touches her hair. Slowly shakes his head and begins to cry. ‘I blew it. Moira, I buggered it up.’

Psychics cry more than most people, he’s learned this.

Simon says, ‘Dave?’

‘He’s OK now,’ Moira says. ‘I think he’s OK. Tom?’

‘Pretty much what you’d expect. Left him in the courtyard, marching round and round.’

‘Go find him, huh? We’ll all go.’ Moira turning back towards the Abbey, the bastard place looking so benign with the glimmering lights in its downstairs windows.

At this point, the session drummer, Lee Gibson, joins them. He’s carrying a long, black torch and grinning. ‘What the fuck was all that about?’

‘I cocked it up,’ Dave says to Moira.

‘Come on, Davey.’ She doesn’t want him talking about this in front of Lee.

‘I screwed up.’ Shaking his head from side to side. ‘You know that. You were there.’

‘Not really, Davey. I only caught the flower.’

‘What have I done, Moira?’

‘Leave it, Davey.’

‘What have I fucking done?’ Keeps rubbing his eyes as if he’s expecting to lose his vision again.

Moira snaps, ‘Stop it.’

Lee’s shaking his head in disbelief, still grinning. ‘You guys really kill me.’

Then, as they enter the courtyard, there’s a bellowing scream. ‘Poor bugger,’ Dave mutters. ‘We should’ve listened to him. Could you make out the circle? Did you see how many candles there were? Did you see what kind of candles?’

‘Davey.’ Moira’s hissing through her teeth. ‘Will you just shut the fuck up!’

Lee Gibson snorts with laughter. Can’t blame him. We’re all terminally neurotic bastards, far as he’s concerned. He’s a normal guy.

The tower house sprouts from a corner of the Abbey. There’s a courtyard with a high stone wall, the fourth side open to the trackway, rough lawns either side of it. Three shadowy vehicles standing in the courtyard. Moira watches poor, frazzled Tom Storey stagger out from behind one of them, the mad bull looking for somebody to gore.

‘Monks!’ Tom’s face is bulging in the beam of Lee’s flashlight. ‘Either side the gate. I’m telling you … two fucking monks.’ And Moira shivers at this.

Russell, the producer, is watching from the doorway. What has he done to deserve this? From Russell’s side of the fence it must be clear enough that whatever’s scaring Tom would hold few fears for a halfway-decent clinical psychiatrist.

‘Candles.’ Tom shuddering and shaking like an old refrigerator. ‘They was holding candles. Bastards.’

‘Come on, squire.’ Simon claps him on the back. ‘We’ll talk about it inside.’

‘No way.’ Tom snatching at Simon’s arm. ‘Time is it?’

‘Half four-ish,’ Moira says. ‘Let’s go down to the kitchen, make some tea, huh?’

Tom scowls. ‘I’m getting out. Russell, keys.’

The big guy’s feverish, incandescent – an unhealthy glow, like radium. ‘Tom, listen …’ Moira reckons that if all the lights suddenly went out they’d still be able to see him. ‘You’re no’ fit to drive, believe me.’

Tom’s face is truly ghastly in Lee’s torchbeam, a Hallowe’en pumpkin. ‘Russell, you don’t gimme the keys to that Land Rover, I’ll tear your fucking head off.’

Moira said, ‘I think we should stop him, Russell.’ But Russell only shrugs helplessly, goes back into the Abbey, shaking his shaven head at the futility of trying to reason with loonies. Just another normal guy.

Tom’s already climbed into the Land Rover, now cranking down the window and shouting out gleefully, ‘S’all right, keys are in.’ There’s a sudden, ludicrous blast of big band music over the courtyard, the Syd Lawrence Orchestra.

‘… this shit?’ Tom stabbing at the radio buttons, searching for the comfort of hard rock music. Then the scrapyard rattle of the engine. ‘Debs shows up in the Lotus, tell her I already split, yeah?’

Moira says, ‘Jesus, can she get into that thing in her condition? Tom, why don’t you come down from there, call her?’

The Land Rover’s headlights have bleared into life, under cakes of red mud; its wheels are spinning, flinging gravel at them. The radio, volume as high as it will go, says,

‘… believed to have been returning home to their apartment near Central Park when the gunman struck.’

‘Listen, my friends.’ Simon guides them into a corner of the courtyard. ‘I hope I’m not speaking out of turn here, but I think we should put the arm on Russell to wipe tonight’s stuff.’

For a moment, Moira thinks she can see a ghastly white light at one of the tower windows, as if the Abbey is registering mild annoyance. The Land Rover clatters across the courtyard towards the main gate.

She sighs gratefully. ‘Took the words out of my head. Will you tell him or will I?’

‘Hey now …’ Lee Gibson is not happy. ‘Let’s not be so friggin’ hasty.’ He’s wearing an ankle-length army greatcoat now, over his moleskin waistcoat. ‘Correct me if I got this wrong’ – echoing Russell – ‘but the whole point of the exercise is that something should get, you know, stirred up, right?’

‘No, look.’ Dave Reilly wanders shakily into Lee’s torch-beam. ‘Better idea. Let’s scrap the lot. Wipe everything.’

‘Wipe …?’ Lee hurls his torch at the ground. The light doesn’t go out; it plays on Dave’s soaked trainers.

‘We don’t need this,’ Dave says. ‘Any of us.’

‘Speak for your fucking self!’ Lee ramming his hands into the pockets of his greatcoat. ‘Wipe the tapes?’ Flapping the skirts of his greatcoat. ‘You can wipe my arse.’

Tail-lights wobble as the Land Rover hits the dirt track. Moira says softly, ‘Lee, this is no’ your problem, OK? You’ll have the full fee, whatever happens.’

‘I don’t believe this.’ Lee turns away in disgust. ‘You bastards need putting away.’

Simon waits until the studio door has slammed behind Lee. ‘Right. We’re obviously not going on with this. I don’t think we need a vote on it, do we?’

‘I think we can safely speak for Tom.’ Dave picks up Lee’s torch. ‘He won’t be back. He’s had it with invoking ghosts.’

‘We all have, Dave. But if we walk away, we have to accept that’s it for the band. Irreconcilable musical difference is, I think, the usual term. We’ll have to say that.’

‘Hang on,’ Dave said, ‘I don’t think I understand.’

‘It’s simple. If we’re still together as a band, Max Goff will sue us for breach of contract. He’ll nail us to the wall. He’ll know we can’t afford the action – except for Tom, maybe, so he’ll try and force us to come back.’

‘Sod that,’ says Dave.

‘But if we’ve split up, he’ll know there’s no prospect of that. He may decide to write us off. What I thought … I’ll … I’ll go and see him myself. Come to an understanding.’

Simon’s face, half-lit, is entirely without expression. Moira knows how much he hates Goff. She also knows that Goff does not hate genteel, willowy Simon. ‘We’ll all go,’ she says carefully.

‘No.’ Simon’s smile is sad, rueful. ‘That wouldn’t be appropriate. I’ll do it.’

Moira watches the Land Rover’s red tail-lights fading into the night mist. She looks up at the Abbey. As usual, it seems to be gazing down on her with an ancient knowledge and a frightening edge of derision. The part housing the studio has a single sawn-off tower, with windows where once, presumably, there were only slits. She looks to Dave, who shakes his head.

‘Too small, too old. This was in a city, I think. Doesn’t matter now, though, does it?’

Moira shakes her head too, knowing that neither of them believes it doesn’t matter, and then she says what she ought to have said hours ago.

Dave, who just a minute ago thought he couldn’t get any colder, cries out, ‘No!’

‘Listen.’ Moira’s is a lonely voice, but calm, all too calm. ‘This has to be the real end. I mean, we’re no’ gonny work together again, are we?’

Adding, as if she can feel him reaching out for her, ‘Davey, love, we’re no’ safe together. We’re too much.’

‘We need each other,’ he protests hopelessly. Knowing she’s shaking her head. He needs her; she doesn’t need him. Or she wouldn’t be saying this.

‘You could’ve … come to some harm tonight, Davey. We’ve become unlucky. Simon knows that, don’t you, Si?’

Simon doesn’t reply. Moira says, more harshly, ‘We’re the band that should never’ve been, a bloody toxic cocktail. We daren’t see each other again.’

Dave turns away, clenching his fists. Wanting to sob. He doesn’t, it would be despicable. How can he possibly walk away, and just forget about her? He’s thinking, wish I’d died, like … like who?

He’s looking towards the east, where there’s no suggestion of a dawn. Around them, there’s an unnatural silence, as if all three know what’s coming next. As if they’re all waiting for the sound which will prove how right Moira is and will snap the spine of the night.

In the long, heartsick days to come, Dave Reilly, approaching his twenty-seventh birthday, is going to drive himself half-crazy playing it all back. Always ending in tears. And flames.

It’s as if time’s mechanisms have gone haywire, all the shattering moments of the night occurring simultaneously in one endlessly distressing present-moment. The dark fortress and the broken glasses and a prolonged rending and mangling of metal. And Moira breathing, ‘Jesus … no?’ – an appeal for divine intercession in the split second before it happens.

Before they turn as one and run out of the entrance onto the slippery track leading into an oblivion of hills and forestry and starless sky, and it begins to rain.

Maybe two hundred yards along the dirt track, they see a lone, steamy headlight beam, pointing vaguely into the sky like a dying prayer and then dissipating into mist. A single, faraway scream is cruelly amplified by the valley, beneath it the distant, almost musical tinkle of collapsing glass, before the night gets sheared into streamers of orange and white.

Twenty yards away, the old blue Land Rover driven by Tom Storey has brought down a low, sleek Lotus Elan, like a lion with a gazelle. The Land Rover has torn into the Lotus and savaged it and its guts are out and still heaving, and Dave can see flames leaping into the vertical rain. A voice is talking crisply from the Land Rover’s radio, but he can’t hear what it’s saying for Simon’s wounded cry,

‘Oh, Jesus, look …’

On the fringe of the burning tableau, surreal in the remote rural night, a large, shadowy, lumbering, crumbling thing is half carrying, half dragging a lumpy, sagging bundle and babbling to it,

‘Debs, Debs, Debsie, Debs, s’gonna be OK, Debsie, s’OK …’

guy’s got no consideration … Eight months gone … Jesus, can she get into that thing, her condition …?

There’s a blast of hard, golden heat from the wreckage; Tom is thrust forward as if he’s been kicked in the small of the back and drops his awful, pitiful burden. Both sleeves of his jacket burst spectacularly into flames, shoulders to cuffs.

As Dave runs towards the heat, a smut floats into his left eye, forcing him to close both of them. He feels like he’s entering hell, hearing Tom bellowing, the hiss of flames and rain and then – like the voice of the Old Testament God from the burning bush – the Land Rover’s radio voice, heavy with history.

‘… and to recap, if you’ve just joined us, it’s now been confirmed that the former Beatle, John Lennon, has died after a shooting incident outside the Dakota apartment block in New York where he and his wife …’

Part One

November 1994

I

Darkness at the Break of …

Maybe you read in the papers about what happened in Liverpool on the 13th of December 1993. Well, anyway, I was there. In the middle of it. Scared me a lot. Not so much at the time – it happened in full daylight. In fact it’s taken me nearly a year to get a perspective on it, but it still …

Crap. Crap, crap, crap.

Scrub it.

Wasn’t what he wanted to write, anyway. Really, he wanted to pour it all out about Jan and the tragic black bonnet business and what it had done to them. But where would that get him? And also … it would be pathetic.

Nearly as bad as his usual please contact me letters, which, getting no replies, had been followed up – weeks, months, years going by – with the please, please, please … just get in touch, write, phone, carrier pigeon, anything …

Talk about pathetic …

Start again.

Dear Moira,

Liverpool. December 13, 1993. I know it was nearly a year ago, but bear with me. Even if you read about it in the papers, the significance would probably pass you by. For everybody here, it was like an act of God. Picture the scene. God’s at a loose end one afternoon. Spots Liverpool out of the corner of an all-seeing eye and He thinks, Yeah, why not …

Or – what about this? – He notices one of His less successful creations strolling along Whitechapel towards the guitar shop and He thinks … that’s bloody Dave Reilly, let’s see if he gets the message this time.

And then He glances at His watch (one of those fancy ones, tells you when it’s teatime in Paraguay), does a little countdown, points His finger and He says, out the corner of His mouth, ‘OK … LET THERE BE DARKNESS!’

Too whimsical. You’ve probably lost her already, pal. If it even reaches her.

This was the other problem. He could never be sure the letters and postcards and Christmas cards and birthday cards were even getting through.

No replies. Could be she thought even communications by post could reawaken things better left comatose, but Dave was buggered if he could see it. Whenever he was locked out in the night, he wrote to Moira. This amounted to a lot of letters.

He’d tried ringing this feller in Glasgow, Malcolm Kaufmann, the agent, but he was always ‘in a meeting’, according to his secretary.

Could Mr Kaufmann perhaps call back?

Aw, the secretary said, between you and me, you’ll be waiting for ever for Mr Kaufmann to call back. My advice would be to write …

And write. And write.

Maybe Moira had directed that all the envelopes addressed in Dave Reilly’s handwriting should go directly into the bin. Dave had thought of this some while back and had one typed, but no reaction to that either; maybe she thought it was a bill.

And yet, even though he’d never seen her since the morning of the 9th of December 1980, she was always there for him. Kind of. For instance, there was the time, after the humiliating failure of his solo album in 1987, when, facing the prospect of having to get a Proper Job and no qualifications, he’d sat down at the piano in Ma’s front room, started plonking the keys, putting on his poshest McCartney voice.

Moira My Dear,

I am reaching out in desperation

Please …

And thought, out of the blue, You know, you could survive on this for a bit. If you can’t be original, why not take the piss out of people who can? And while you might not be technically as good at it as some, there are ways you can make up for that. Like going into the quiet place, absorbing the essences …

Look, the only way I can handle this thing, he’d once said to Moira, is to try and channel it into creativity. To make something lasting and positive out of it. Isn’t that what art is?

Ah, the idealism of youth. Maturity tells you that if all that comes back in your face, if you can’t make anything lasting and positive out of it, don’t mess around … put it into something negative and transient.

Yes. Well. No wonder Moira had looked distinctly dubious.

Anyway, I was in town that day, Monday, December 13, for a little gig (I’m not going to tell you where it was, I do have some pride).

I’d gone to buy a few sets of strings at this little music shop which sells me them in bulk. The guy there was trying to flog me a secondhand acoustic guitar, a Takamine – Japanese, brilliant built-in pick-up with sound-balancing, everybody’s using them, ultra-reliable – you know the way they go on.

But I was in a relatively good mood. For the time of year. It’s always a relief when the 8th of December goes past and nothing destroys me. So, anyway, I was giving it a go, this guitar, and for some reason I started playing ‘Julia’, the Lennon song off the White Album, the one introducing Yoko to his dead mother. The one I never could rewrite for laughs.

Well, I must have been feeling wistful, you know how it is. I was doing the voice, which is John at his most ethereal. I always like the opening of that one – about half of what he says being meaningless, but he says it just to reach you, Julia … It’s so personal and spiritual, much more so than the self-indulgent primal scream stuff on the Plastic Ono Band album.

Anyway, it was just after one o’clock, everybody buggering off for lunch, the pubs filling up, and I’m perching on an amplifier, droning out ‘Julia’, feeling unusually … wistful (I can’t get away from this bloody word ‘wistful’, but you know what I mean, kind of coasting on memory, but nothing more complicated than that … or so I thought) and I remember looking down and seeing something glistening on the curve of the guitar, just above the pick-up, a blob of liquid, and then another one landed next to it.

Plop.

Well, of course, it was a bloody tear, wasn’t it?

I was really embarrassed. But at least it was Liverpool, where more tears have been shed into more pints over that bastard …

Anyway, the feller who runs the shop comes over – he’d been watching me, not saying a word. So when he sees I’ve finally noticed him, he wanders across, big grin. ‘Got to buy it now, matey, you’ve christened the bugger. That’ll be nine hundred and thirty five quid, including discount.’

I’m thinking, You dickhead. Not him, me.

Then the lights go out.

Bang.

You’re never going to send this, pal. Might as well admit it. You’re just tormenting yourself.

Dave was writing it on the card table in his old bedroom at Ma’s bungalow in Hoylake, on the Wirral, where the seagulls cruised past the window and crapped on the glass.

Always used to stay here when he was working clubs and pubs in Liverpool and the North West, even though it depressed the hell out of him. Now, with the Jan thing on the blink, he was killing time, gearing up for a final rescue bid.

In a situation like this, he always wrote to Moira, which was as much use as writing to Santa Claus and sending it up the chimney, but must be therapeutic because he was unloading it, like – presumably – spilling it all to an analyst.

On the wall, directly facing him, was a reproachful picture of the matryred John Lennon, going yellow now, like the adjacent poster from inside the Beatles’ White Album, which, twenty years ago he’d – presciently, no doubt – had framed in black.

In fact, apart from his own artwork for the first Philosopher’s Stone album, the room was still the way it had been when he was a student, back when the world was innocent. ‘When you’re famous,’ his ma used to say, ‘I’ll open it to the public at a fiver a time.’

Even she must be realizing the prospect of Dave becoming famous was about as likely now as the seagulls flying off to crap somewhere else.

The old girl had a man friend these days and went off on regular ‘dates’ in this feller’s ancient Morris Oxford, sometimes staying out all night. She was seventy.

Before Jan, Dave had lived for brief periods with four women, all of whom had known about him or learned very quickly. (The sudden coldness of the bedroom sometimes in the early hours, the way owls would always find them, even in the city.) Initially they’d been excited by it. It was his bit of ‘charisma’. (Moira used to talk, quite cynically, about her ‘glamour’.) But it faded fast.

If he was ever to trap some happiness, it could only be with a woman he couldn’t frighten, and he’d only ever met one, and among her last words to him had been the endlessly echoing

we’re no gonny see each other again, ever.

And she’d never replied to his letters.

I mean all the lights went out. Everywhere.

Remember Dylan’s line about darkness at the break of noon. This one was just over an hour after noon, but I’ll get to that.

Well, obviously, we thought it was just the shop, at first. I said, ‘You shouldn’t keep waiting for the red bill, Percy, sometimes they forget.’ Then we go out into the street and everybody’s lights have gone, and I can hear this terrible screeching of brakes from the main road around the corner – I mean, not just one screech but a whole chorus of screeches, and it’s obvious what’s happened – the bloody traffic lights have all gone out.

Well, I couldn’t have bought Percy’s Takamine even if I’d had the money – the bloody till wouldn’t work. So I walk out into the centre of town, and it’s like the end of the world’s been announced. Some people are really panicking – I mean, everybody’s had a power cut at home, maybe even the whole street’s been off … but an entire city? Customers and office workers trapped in lifts? Streets clogged with cars and buses and taxis? Trains frozen in coal-black underground stations?

This is not natural.

And it’s dead eerie, somehow. Although far from quiet, what with the streets full of police trying to get the traffic flowing again, shops being locked in customers’ faces because of the looting threat.

I remember this feller banging on the door of a newsagent’s shouting, Hey, come on, gissa packet a ciggies, will yer? Just one packet, yer bastards!

And there’s a woman rushing out of a hairdresser’s with half a perm and her face all smudged clutching a towel and grabbing hold of people, screaming, You’ve gorra help me! He’s taking me out tonight, it’s me anniversary!

Which might have been funny if she hadn’t been wearing (oh God, oh Jesus Christ) the black bonnet.

Half an hour later, the rumours are spreading. Some people are saying it’s the IRA, and a woman at a burger stall with its own generator is doing fantastic business and telling one customer after another, ‘It’s not just Liverpool, you know, luv, it’s the whole country that’s been blacked out! You’ve had it for hot meals now. Gerrit while you can!’

It wasn’t, of course. It was just Liverpool, as if that wasn’t bad enough and totally unprecedented – a hundred thousand electricity users cut off for the best part of two hours, shops and businesses losing millions of pounds.

According to next day’s Daily Post, a spokesman for the National Grid said it had been caused by ‘an outside body’. It was eventually traced to the valves on two transformers in the Lister Drive power station at Tuebrook. This is one of the places which passes on the juice from the National Grid to the local lecky company, MANWEB.

In the DP the following day, a MANWEB official was quoted as saying it was ‘extraordinary’ two transformers going down at once. A ‘million to one chance’, an ‘untimely coincidence’.

And then another unnamed spokesman actually said, ‘The fates came together on this one.’

Interesting, isn’t it, that when official bodies can’t explain something, they still revert to expressions like ‘the fates’.

Was it ever actually love all those years ago? Or just a subconscious plea for empathy?

If it didn’t come back to John Lennon, it always came back to Moira. In the spring of 1981, he’d decided he couldn’t stand this any more and set out to find her.

This meant Scotland. He’d rung all the people he knew up there – about five of them, mainly musicians. One guy said, yeah, she was certainly gigging, done some support for Clannad, he was sure she had. Another said, hang on a mo, there was a line or two in the local rag – Aberdeen University – the 20th, was it?

So Dave had loaded up his van with all the clean clothes he could gather together, thrown an old mattress in the back in case he ran out of cash. And the Martin guitar, in case he had to sell it, perish the thought.

Well, actually, the guitar was also there because of this little fantasy he had. A darkened folk club somewhere picturesque and atmospheric, and she’d be doing her act with everybody sitting around quietly, revering her. And then she’d get on, solo, to a song which really could have used a second guitar, a few harmonies. She’d be in a long black dress, and when she reached the chorus she’d sound so alone you could die.

At which point … … another guitar, the incomparable Martin, would join in from the back of the hall, getting louder as the figure from the past weaved between the bodies towards her, looking as handsome as ever but maybe a little weary; he’d travelled a long way, after all …

Dave still cringed over this.

Spring had been late that year. Especially in Scotland. Snowdrifts in March, the travelling hard, especially in a nine-year-old Ford Thames. And when he got to Aberdeen University, there was no concert on the 20th involving Moira Cairns.

Moira who? She wasn’t even that well known. She’d made one album of her own songs – including The Comb Song – and then gone back to the traditional folk stuff. She was not famous; she had a following. He didn’t know about Malcolm Kaufmann in those days; maybe the agent hadn’t yet come on the scene.

It was hopeless. She didn’t seem to work to any kind of pattern. Or she knew somehow that he was around.

Example. He’d turn up at some pub in, say, a fishing village in Fife, having spent most of a week on the trail and just enough money left for a night’s B and B, and he’d find it was last night, she’d already been on, fixture altered by request of the artist.

This would keep happening, in different ways. Town halls, theatres, arts centres, students’ unions … always last night, or it had been postponed, or it was the wrong town, or it was the right town and the bloody van broke down and he arrived too late.

All of this happening in a kind of haze, like in those infuriating dreams where you’re trying your damnedest to do something dead simple, like make a phone call, and your fingers keep hitting the wrong numbers. Each day he’d set out with the certainty that this time … And each night he’d wind up confused and knackered, getting pissed and weeping off the quay at Oban or somewhere.

She was always ahead of him, always the next town along the line, and an impenetrable mist between them.

Some days he’d climb a hill and stand with his hands spread and his eyes closed. Where are you? Just give me a direction. Like the way he’d reach out for her mind on stage or during a session when a song took off on its own. We going into the chorus again, or wind it up?

Nothing.

And then he’d got ill, running a temperature. Couldn’t even drive home. Lay sweating on the mattress in the back of the van until he must have passed out or something and the next thing he remembers he’s in an ambulance and then a hospital and someone is saying, Nothing obvious, looks like plain old nervous exhaustion to me.

Next thing, he’s sitting up in a cold sweat, throwing off the blankets, screaming, the Martin!

Who is this Martin, Mr Reilly? Is he a friend?

The bloody Martin’s still in the bloody van!

It wasn’t, naturally. Fifteen hundred quid’s worth of customized, hand-tooled acoustic guitar. They hadn’t taken the van; even thieves have standards.

He’d never been back to Scotland.

OK, read this carefully. Read it twice.

The official time of the Liverpool blackout was 1.13 p.m.

It was the thirteenth minute of the thirteenth hour of the thirteenth day of December.

Fact.

Another one of those untimely coincidences the electricity company was on about.

It spooked me, kid. I couldn’t keep a limb still when I read that. I don’t like December, how could I? What about you? Do things happen to you in December? Do you start to get nervous when the nights are growing longer?

It’s November now, coming up to a year since the big Liverpool blackout. Worried? Me?

Bloody right I am.

Here’s another untimely coincidence that never made the papers – they probably thought it was too bloody stupid to mention.