Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: A Darker Shade of Magic

- Sprache: Englisch

Most people only know one London; but what if there were several? Kell is one of the last Travelers—magicians with a rare ability to travel between parallel Londons. There's Grey London, dirty and crowded and without magic, home to the mad king George III. There's Red London, where life and magic are revered. Then, White London, ruled by whoever has murdered their way to the throne. But once upon a time, there was Black London...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 509

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by V.E. Schwab

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

I: The Traveler

I

II

III

II: Red Royal

I

II

III

III: Grey Thief

I

II

III

IV: White Throne

I

II

III

IV

V

V: Black Stone

I

II

III

IV

V

VI: Thieves Meet

I

II

III

IV

VII: The Follower

I

II

III

VIII: An Arrangement

I

II

III

IX: Festival & Fire

I

II

III

IV

X: One White Rook

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

XI: Masquerade

I

II

III

IV

V

XII: Sanctuary & Sacrifice

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

XIII: The Waiting King

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

XIV: The Final Door

I

II

III

IV

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

Also by V.E. SCHWAB and available from TITAN BOOKS

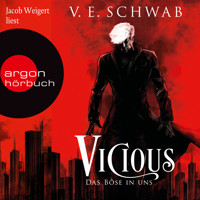

Vicious

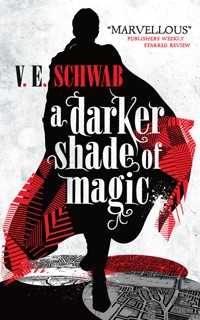

A DARKER SHADE OF MAGIC

Print edition ISBN: 9781783295401

E-book edition ISBN: 9781783295418

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First Titan edition: February 2015

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

V.E Schwab asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright © 2015 V.E Schwab.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

What did you think of this book?

We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website:

www.titanbooks.com

For the ones who dream of stranger worlds

Such is the quandary when it comes to magic, that it is not an issue of strength but of balance. For too little power, and we become weak. Too much, and we become something else entirely.

TIEREN SERENSE,head priest of the London Sanctuary

I

THE TRAVELER

I

Kell wore a very peculiar coat.

It had neither one side, which would be conventional, nor two, which would be unexpected, but several, which was, of course, impossible.

The first thing he did whenever he stepped out of one London and into another was take off the coat and turn it inside out once or twice (or even three times) until he found the side he needed. Not all of them were fashionable, but they each served a purpose. There were ones that blended in and ones that stood out, and one that served no purpose but of which he was just particularly fond.

So when Kell passed through the palace wall and into the anteroom, he took a moment to steady himself—it took its toll, moving between worlds—and then shrugged out of his red, high-collared coat and turned it inside out from right to left so that it became a simple black jacket. Well, a simple black jacket elegantly lined with silver thread and adorned with two gleaming columns of silver buttons. Just because he adopted a more modest palette when he was abroad (wishing neither to offend the local royalty nor to draw attention) didn’t mean he had to sacrifice style.

Oh, kings, thought Kell as he fastened the buttons on the coat. He was starting to think like Rhy.

On the wall behind him, he could just make out the ghosted symbol made by his passage. Like a footprint in sand, already fading.

He’d never bothered to mark the door from this side, simply because he never went back this way. Windsor’s distance from London was terribly inconvenient considering the fact that, when traveling between worlds, Kell could only move between a place in one and the same exact place in another. Which was a problem because there was no Windsor Castle a day’s journey from Red London. In fact, Kell had just come through the stone wall of a courtyard belonging to a wealthy gentleman in a town called Disan. Disan was, on the whole, a very pleasant place.

Windsor was not.

Impressive, to be sure. But not pleasant.

A marble counter ran against the wall, and on it a basin of water waited for him, as it always did. He rinsed his bloody hand, as well as the silver crown he’d used for passage, then slipped the cord it hung on over his head, and tucked the coin back beneath his collar. In the hall beyond, he could hear the shuffle of feet, the low murmur of servants and guards. He’d chosen the anteroom specifically to avoid them. He knew very well how little the Prince Regent liked him being here, and the last thing Kell wanted was an audience, a cluster of ears and eyes and mouths reporting the details of his visit back to the throne.

Above the counter and the basin hung a mirror in a gilded frame, and Kell checked his reflection quickly—his hair, a reddish brown, swept down across one eye, and he did not fix it, though he did take a moment to smooth the shoulders of his coat—before passing through a set of doors to meet his host.

The room was stiflingly warm—the windows latched despite what looked like a lovely October day—and a fire raged oppressively in the hearth.

George III sat beside it, a robe dwarfing his withered frame and a tea tray untouched before his knees. When Kell came in, the king gripped the edges of his chair.

“Who’s there?” he called out without turning. “Robbers? Ghosts?”

“I don’t believe ghosts would answer, Your Majesty,” said Kell, announcing himself.

The ailing king broke into a rotting grin. “Master Kell,” he said. “You’ve kept me waiting.”

“No more than a month,” he said, stepping forward.

King George squinted his blind eyes. “It’s been longer, I’m sure.”

“I promise, it hasn’t.”

“Maybe not for you,” said the king. “But time isn’t the same for the mad and the blind.”

Kell smiled. The king was in good form today. It wasn’t always so. He was never sure what state he’d find his majesty in. Perhaps it had seemed like more than a month because the last time Kell visited, the king had been in one of his moods, and Kell had barely been able to calm his fraying nerves long enough to deliver his message.

“Maybe it’s the year that has changed,” continued the king, “and not the month.”

“Ah, but the year is the same.”

“And what year is that?”

Kell’s brow furrowed. “Eighteen nineteen,” he said.

A cloud passed across King George’s face, and then he simply shook his head and said, “Time,” as if that one word could be to blame for everything. “Sit, sit,” he added, gesturing at the room. “There must be another chair here somewhere.”

There wasn’t. The room was shockingly sparse, and Kell was certain the doors in the hall were locked and unlocked from without, not within.

The king held out a gnarled hand. They’d taken away his rings, to keep him from hurting himself, and his nails were cut to nothing.

“My letter,” he said, and for an instant Kell saw a glimmer of George as he once was. Regal.

Kell patted the pockets of his coat and realized he’d forgotten to take the notes out before changing. He shrugged out of the jacket and returned it for a moment to its red self, digging through its folds until he found the envelope. When he pressed it into the king’s hand, the latter fondled it and caressed the wax seal—the red throne’s emblem, a chalice with a rising sun—then brought the paper to his nose and inhaled.

“Roses,” he said wistfully.

He meant the magic. Kell never noticed the faint aromatic scent of Red London clinging to his clothes, but whenever he traveled, someone invariably told him that he smelled like freshly cut flowers. Some said tulips. Others stargazers. Chrysanthemums. Peonies. To the king of England, it was always roses. Kell was glad to know it was a pleasant scent, even if he couldn’t smell it. He could smell Grey London (smoke) and White London (blood), but to him, Red London simply smelled like home.

“Open it for me,” instructed the king. “But don’t mar the seal.”

Kell did as he was told, and withdrew the contents. For once, he was grateful the king could no longer see, so he could not know how brief the letter was. Three short lines. A courtesy paid to an ailing figurehead, but nothing more.

“It’s from my queen,” explained Kell.

The king nodded. “Go on,” he commanded, affecting a stately countenance that warred with his fragile form and his faltering voice. “Go on.”

Kell swallowed. “‘Greetings to his majesty, King George III,’” he read, “‘from a neighboring throne.’”

The queen did not refer to it as the red throne, or send greetings from Red London (even though the city was in fact quite crimson, thanks to the rich, pervasive light of the river), because she did not think of it that way. To her, and to everyone else who inhabited only one London, there was little need to differentiate among them. When the rulers of one conversed with those of another, they simply called them others, or neighbors, or on occasion (and particularly in regard to White London) less flattering terms.

Only those few who could move among the Londons needed a way to keep them straight. And so Kell—inspired by the lost city known to all as Black London—had given each remaining capital a color.

Grey for the magic-less city.

Red, for the healthy empire.

White, for the starving world.

In truth, the cities themselves bore little resemblance to one another (and the countries around and beyond bore even less). The fact they were all called London was its own mystery, though the prevailing theory was that one of the cities had taken the name long ago, before the doors were all sealed and the only things allowed through were letters between kings and queens. As to which city had first laid claim to the name, none could agree.

“‘We hope to learn that you are well,’” continued the queen’s letter, “‘and that the season is as fair in your city as it is in ours.’”

Kell paused. There was nothing more, save a signature. King George wrung his hands.

“Is that all it says?” he asked.

Kell hesitated. “No,” he said, folding the letter. “That’s only the beginning.”

He cleared his throat and began to pace as he pulled his thoughts together and put them into the queen’s voice. “Thank you for asking after our family, she says. The King and I are well. Prince Rhy, on the other hand, continues to impress and infuriate in equal measure, but has at least gone the month without breaking his neck or taking an unsuitable bride. Thanks be to Kell alone for keeping him from doing either, or both.”

Kell had every intention of letting the queen linger on his own merits, but just then the clock on the wall chimed five, and Kell swore under his breath. He was running late.

“Until my next letter,” he finished hurriedly, “stay happy and stay well. With fondness. Her Highness Emira, Queen of Arnes.”

Kell waited for the king to say something, but his blind eyes had a steady, faraway look, and Kell feared he had lost him. He set the folded note on the tea tray and was halfway to the wall when the king spoke up.

“I don’t have a letter for her,” he murmured.

“That’s all right,” said Kell softly. The king hadn’t been able to write one for years. Some months he tried, dragging the quill haphazardly across the parchment, and some months he insisted on having Kell transcribe, but most months he simply told Kell the message and Kell promised to remember.

“You see, I didn’t have the time,” added the king, trying to salvage a vestige of his dignity. Kell let him have it.

“I understand,” he said. “I’ll give the royal family your regards.”

Kell turned again to go, and again the old king called out to stop him.

“Wait, wait,” he said. “Come back.”

Kell paused. His eyes went to the clock. Late, and getting later. He pictured the Prince Regent sitting at his table in St. James, gripping his chair and quietly stewing. The thought made Kell smile, so he turned back toward the king as the latter pulled something from his robe with fumbling fingers.

It was a coin.

“It’s fading,” said the king, cupping the metal in his weathered hands as if it were precious and fragile. “I can’t feel the magic anymore. Can’t smell it.”

“A coin is a coin, Your Majesty.”

“Not so and you know it,” grumbled the old king. “Turn out your pockets.”

Kell sighed. “You’ll get me in trouble.”

“Come, come,” said the king. “Our little secret.”

Kell dug his hand into his pocket. The first time he had visited the king of England, he’d given him a coin as proof of who he was and where he came from. The story of the other Londons was entrusted to the crown and handed down heir to heir, but it had been years since a traveler had come. King George had taken one look at the sliver of a boy and squinted and held out his meaty hand, and Kell had set the coin in his palm. It was a simple lin, much like a grey shilling, only marked with a red star instead of a royal face. The king closed his fist over the coin and brought it to his nose, inhaling its scent. And then he’d smiled, and tucked the coin into his coat, and welcomed Kell inside.

From that day on, every time Kell paid his visit, the king would insist the magic had worn off the coin, and make him trade it for another, one new and pocket-warm. Every time Kell would say it was forbidden (it was, expressly), and every time the king would insist that it could be their little secret, and Kell would sigh and fetch a fresh bit of metal from his coat.

Now he plucked the old lin out of the king’s palm and replaced it with a new one, folding George’s gnarled fingers gently over it.

“Yes, yes,” cooed the ailing king to the coin in his palm.

“Take care,” said Kell as he turned to go.

“Yes, yes,” said the king, his focus fading until he was lost to the world, and to his guest.

Curtains gathered in the corner of the room, and Kell pulled the heavy material aside to reveal a mark on the patterned wallpaper. A simple circle, bisected by a line, drawn in blood a month ago. On another wall in another room in another palace, the same mark stood. They were as handles on opposite sides of the same door.

Kell’s blood, when paired with the token, allowed him to move between the worlds. He needn’t specify a place because wherever he was, that’s where he’d be. But to make a door within a world, both sides had to be marked by the same exact symbol. Close wasn’t close enough. Kell had learned that the hard way.

The symbol on the wall was still clear from his last visit, the edges only slightly smeared, but it didn’t matter. It had to be redone.

He rolled up his sleeve and freed the knife he kept strapped to the inside of his forearm. It was a lovely thing, that knife, a work of art, silver from tip to hilt and monogrammed with the letters K and L.

The only relic from another life.

A life he didn’t know. Or at least, didn’t remember.

Kell brought the blade to the back of his forearm. He’d already carved one line today, for the door that brought him this far. Now he carved a second. His blood, a rich ruby red, welled up and over, and he returned the knife to its sheath and touched his fingers to the cut and then to the wall, redrawing the circle and the line that ran through it. Kell guided his sleeve down over the wound—he’d treat all the cuts once he was home—and cast a last glance back at the babbling king before pressing his palm flat to the mark on the wall.

It hummed with magic.

“As Tascen,” he said. Transfer.

The patterned paper rippled and softened and gave way under his touch, and Kell stepped forward and through.

II

Between one stride and the next, dreary Windsor became elegant St. James. The stuffy cell of a room gave way to bright tapestries and polished silver, and the mad king’s mumblings were replaced by a heavy quiet and a man sitting at the head of an ornate table, gripping a goblet of wine and looking thoroughly put out.

“You’re late,” observed the Prince Regent.

“Apologies,” said Kell with a too-short bow. “I had an errand.”

The Prince Regent set down his cup. “I thought I was your errand, Master Kell.”

Kell straightened. “My orders, Your Highness, are to see to the king first.”

“I wish you wouldn’t indulge him,” said the Prince Regent, whose name was also George (Kell found the Grey London habit of sons taking father’s names both redundant and confusing) with a dismissive wave of his hand. “It gets his spirits up.”

“Is that a bad thing?” asked Kell.

“For him, yes. He’ll be in a frenzy later. Dancing on the tables talking of magic and other Londons. What trick did you do for him this time? Convince him he could fly?”

Kell had only made that mistake once. He learned on his next visit that the King of England had nearly walked out a window. On the third floor. “I assure you I gave no demonstrations.”

Prince George pinched the bridge of his nose. “He cannot hold his tongue the way he used to. It’s why he is confined to quarters.”

“Imprisoned, then?”

Prince George ran his hand along the table’s gilded edge. “Windsor is a perfectly respectable place to be kept.”

A respectable prison is still a prison, thought Kell, withdrawing a second letter from his coat pocket. “Your correspondence.”

The prince forced him to stand there as he read the note (he never commented on the way it smelled of flowers), and then as he withdrew a half-finished reply from the inside pocket of his coat and completed it. He was clearly taking his time in an effort to spite Kell, but Kell didn’t mind. He occupied himself by drumming his fingers on the edge of the gilded table. Each time he made it from pinky to forefinger, one of the room’s many candles went out.

“Must be a draft,” he said absently while the Prince Regent’s grip tightened on his quill. By the time he finished the note, he’d broken two and was in a bad mood, while Kell found his own disposition greatly improved.

He held out his hand for the letter, but the Prince Regent did not give it to him. Instead, he pushed up from his table. “I’m stiff from sitting. Walk with me.”

Kell wasn’t a fan of the idea, but since he couldn’t very well leave empty-handed, he was forced to oblige. But not before pocketing the prince’s latest unbroken quill from the table.

“Will you go straight back?” asked the prince as he led Kell down a hall to a discreet door half concealed by a curtain.

“Soon,” said Kell, trailing by a stride. Two members of the royal guard had joined them in the hall and now slunk behind like shadows. Kell could feel their eyes on him, and he wondered how much they’d been told about their guest. The royals were always expected to know, but the understanding of those in their service was left to their discretion.

“I thought your only business was with me,” said the prince.

“I’m a fan of your city,” responded Kell lightly. “And what I do is draining. I’ll go for a walk and get some air, then make my way back.”

The prince’s mouth was a thin grim line. “I fear the air is not as replenishing here in the city as in the countryside. What is it you call us … Grey London? These days that is far too apt a name. Stay for dinner.” The prince ended nearly every sentence with a period. Even the questions. Rhy was the same way, and Kell thought it must simply be a by-product of never being told no.

“You’ll fare better here,” pressed the prince. “Let me revive you with wine and company.”

It seemed a kind enough offer, but the Prince Regent didn’t do things out of kindness.

“I cannot stay,” said Kell.

“I insist. The table is set.”

And who is coming? wondered Kell. What did the prince want? To put him on display? Kell often suspected that he would like to do as much, if for no other reason than that the younger George found secrets cumbersome, preferring spectacle. But for all his faults, the prince wasn’t a fool, and only a fool would give someone like Kell a chance to stand out. Grey London had forgotten magic long ago. Kell wouldn’t be the one to remind them of it.

“A lavish kindness, your highness, but I am better left a specter than made a show.” Kell tipped his head so that his copper hair tumbled out of his eyes, revealing not only the crisp blue of the left one but the solid black of the right. A black that ran edge to edge, filling white and iris both. There was nothing human about that eye. It was pure magic. The mark of a blood magician. Of an Antari.

Kell relished what he saw in the Prince Regent’s eyes when they tried to hold Kell’s gaze. Caution, discomfort … and fear.

“Do you know why our worlds are kept separate, Your Highness?” He didn’t wait for the prince to answer. “It is to keep yours safe. You see, there was a time, ages ago, when they were not so separate. When doors ran between your world and mine, and others, and anyone with a bit of power could pass through. Magic itself could pass through. But the thing about magic,” added Kell, “is that it preys on the strong-minded and the weak-willed, and one of the worlds couldn’t stop itself. The people fed on the magic and the magic fed on them until it ate their bodies and their minds and then their souls.”

“Black London,” whispered the Prince Regent.

Kell nodded. He hadn’t given that city its color mark. Everyone—at least everyone in Red London and White, and those few in Grey who knew anything at all—knew the legend of Black London. It was a bedtime story. A fairy tale. A warning. Of the city—and the world—that wasn’t, anymore.

“Do you know what Black London and yours have in common, Your Highness?” The Prince Regent’s eyes narrowed, but he didn’t interrupt. “Both lack temperance,” said Kell. “Both hunger for power. The only reason your London still exists is because it was cut off. It learned to forget. You do not want it to remember.” What Kell didn’t say was that Black London had a wealth of magic in its veins, and Grey London hardly any; he wanted to make a point. And by the looks of it, he had. This time, when he held out his hand for the letter, the prince didn’t refuse, or even resist. Kell tucked the parchment into his pocket along with the stolen quill.

“Thank you, as ever, for your hospitality,” he said, offering an exaggerated bow.

The Prince Regent summoned a guard with a single snap of his fingers. “See that Master Kell gets where he is going.” And then, without another word, he turned and strode away.

The royal guards left Kell at the edge of the park. St. James Palace loomed behind him. Grey London lay ahead. He took a deep breath and tasted smoke on the air. As eager as he was to get back home, he had some business to attend to, and after dealing with the king’s ailments and the prince’s attitude, Kell could use a drink. He brushed off his sleeves, straightened his collar, and set out toward the heart of the city.

His feet carried him through St. James Park, down an ambling dirt path that ran beside the river. The sun was setting, and the air was crisp if not clean, a fall breeze fluttering the edges of his black coat. He came upon a wooden footbridge that spanned the stream, and his boots sounded softly as he crossed it. Kell paused at the arc of the bridge, Buckingham House lantern-lit behind him and the Thames ahead. Water sloshed gently under the wooden slats, and he rested his elbows on the rail and stared down at it. When he flexed his fingers absently, the current stopped, the water stilling, smooth as glass, beneath him.

He considered his reflection.

“You’re not that handsome,” Rhy would say whenever he caught Kell gazing into a mirror.

“I can’t get enough of myself,” Kell would answer, even though he was never looking at himself—not all of himself anyway—only his eye. His right one. Even in Red London, where magic flourished, the eye set him apart. Marked him always as other.

A tinkling laugh sounded off to Kell’s right, followed by a grunt, and a few other, less distinct noises, and the tension went out of his hand, the stream surging back into motion beneath him. He continued on until the park gave way to the streets of London, and then the looming form of Westminster. Kell had a fondness for the abbey, and he nodded to it, as if to an old friend. Despite the city’s soot and dirt, its clutter and its poor, it had something Red London lacked: a resistance to change. An appreciation for the enduring, and the effort it took to make something so.

How many years had it taken to construct the abbey? How many more would it stand? In Red London, tastes turned as often as seasons, and with them, buildings went up and came down and went up again in different forms. Magic made things simple. Sometimes, thought Kell, it made things too simple.

There had been nights back home when he felt like he went to bed in one place and woke up in another.

But here, Westminster Abbey always stood, waiting to greet him.

He made his way past the towering stone structure, through the streets, crowded with carriages, and down a narrow road that hugged the dean’s yard, walled by mossy stone. The narrow road grew narrower still before it finally stopped in front of a tavern.

And here Kell stopped, too, and shrugged out of his coat. He turned it once more from right to left, exchanging the black affair with silver buttons for a more modest, street-worn look: a brown high-collared jacket with fraying hems and scuffed elbows. He patted the pockets and, satisfied that he was ready, went inside.

III

The Stone’s Throw was an odd little tavern.

Its walls were dingy and its floors were stained, and Kell knew for a fact that its owner, Barron, watered down the drinks, but despite it all, he kept coming back.

It fascinated him, this place, because despite its grungy appearance and grungier customers, the fact was that, by luck or design, the Stone’s Throw was always there. The name changed, of course, and so did the drinks it served, but at this very spot in Grey, Red, and White London alike, stood a tavern. It wasn’t a source, per se, not like the Thames, or Stonehenge, or the dozens of lesser-known beacons of magic in the world, but it was something. A phenomenon. A fixed point.

And since Kell conducted his affairs in the tavern (whether the sign read the Stone’s Throw, or the Setting Sun, or the Scorched Bone), it made Kell himself a kind of fixed point, too.

Few people would appreciate the poetry. Holland might. If Holland appreciated anything.

But poetry aside, the tavern was a perfect place to do business. Grey London’s rare believers—those whimsical few who clung to the idea of magic, who caught hold of a whisper or a whiff—gravitated here, drawn by the sense of something else, something more. Kell was drawn to it, too. The difference was that he knew what was tugging at them.

Of course, the magically inclined patrons of the Stone’s Throw weren’t drawn only by the subtle, bone-deep pull of power, or the promise of something different, something more. They were also drawn by him. Or at least, the rumor of him. Word of mouth was its own kind of magic, and here, in the Stone’s Throw, word of the magician passed men’s lips as often as the diluted ale.

He studied the amber liquid in his own cup.

“Evening, Kell,” said Barron, pausing to top off his drink.

“Evening, Barron,” said Kell.

It was as much as they ever said to each other.

The owner of the Stone’s Throw was built like a brick wall—if a brick wall decided to grow a beard—tall and wide and impressively steady. No doubt Barron had seen his share of strange, but it never seemed to faze him.

Or if it did, he knew how to keep it to himself.

A clock on the wall behind the counter struck seven, and Kell pulled a trinket from his now-worn brown coat. It was a wooden box, roughly the size of his palm and fastened with a simple metal clasp. When he undid the clasp and slid the lid off with his thumb, the box unfolded into a game board with five grooves, each of which held an element.

In the first groove, a lump of earth.

In the second, a spoon’s worth of water.

In the third, in place of air, sat a thimble of loose sand.

In the fourth, a drop of oil, highly flammable.

And in the fifth, final groove, a bit of bone.

Back in Kell’s world, the box and its contents served not only as a toy, but as a test, a way for children to discover which elements they were drawn to, and which were drawn to them. Most quickly outgrew the game, moving on to either spellwork or larger, more complicated versions as they honed their skills. Because of both its prevalence and its limitations, the element set could be found in almost every household in Red London, and most likely in the villages beyond, (though Kell could not be certain). But here, in a city without magic, it was truly rare, and Kell was certain his client would approve. After all, the man was a Collector.

In Grey London, only two kinds of people came to find Kell.

Collectors and Enthusiasts.

Collectors were wealthy and bored and usually had no interest in magic itself—they wouldn’t know the difference between a healing rune and a binding spell—and Kell enjoyed their patronage immensely.

Enthusiasts were more troublesome. They fancied themselves true magicians, and wanted to purchase trinkets, not for the sake of owning them or for the luxury of putting them on display, but for use. Kell did not like Enthusiasts—in part because he found their aspirations wasted, and in part because serving them felt so much closer to treason—which is why, when a young man came to sit beside him, and Kell looked up, expecting his Collector client and finding instead an unknown Enthusiast, his mood soured considerably.

“Seat taken?” asked the Enthusiast, even though he was already sitting.

“Go away,” said Kell evenly.

But the Enthusiast did not leave.

Kell knew the man was an Enthusiast—he was gangly and awkward, his jacket a fraction too short for his build, and when he brought his long arms to rest on the counter and the fabric inched up, Kell could make out the end of a tattoo. A poorly drawn power rune meant to bind magic to one’s body.

“Is it true?” the Enthusiast persisted. “What they say?”

“Depends on who’s talking,” said Kell, closing the box, sliding the lid and clasp back into place, “and what’s being said.” He had done this dance a hundred times. Out of the corner of his blue eye he watched the man’s lips choreograph his next move. If he’d been a Collector, Kell might have cut him some slack, but men who waded into waters claiming they could swim should not need a raft.

“That you bring things,” said the Enthusiast, eyes darting around the tavern. “Things from other places.”

Kell took a sip of his drink, and the Enthusiast took his silence for assent.

“I suppose I should introduce myself,” the man went on. “Edward Archibald Tuttle, the third. But I go by Ned.” Kell raised a brow. The young Enthusiast was obviously waiting for him to respond with an introduction of his own, but as the man clearly already had a notion of who he was, Kell bypassed the formalities and said, “What do you want?”

Edward Archibald—Ned—twisted in his seat, and leaned in conspiratorially. “I’m looking for a bit of earth.”

Kell tipped his glass toward the door. “Check the park.”

The young man managed a low, uncomfortable laugh. Kell finished his drink. A bit of earth. It seemed like a small request. It wasn’t. Most Enthusiasts knew that their own world held little power, but many believed that possessing a piece of another world would allow them to tap into its magic.

And there was a time when they would have been right. A time when the doors stood open at the sources, and power flowed between the worlds, and anyone with a bit of magic in their veins and a token from another world could not only tap into that power, but could also move with it, step from one London to another.

But that time was gone.

The doors were gone. Destroyed centuries ago, after Black London fell and took the rest of its world with it, leaving nothing but stories in its wake. Now only the Antari possessed enough power to make new doors, and even then only they could pass through them. Antari had always been rare, but none knew how rare until the doors were closed, and their numbers began to wane. The source of Antari power had always been a mystery (it followed no bloodline) but one thing was certain: the longer the worlds were kept apart, the fewer Antari emerged.

Now, Kell and Holland seemed to be the last of a rapidly dying breed.

“Well?” pressed Ned. “Will you bring me the earth or not?”

Kell’s eyes went to the tattoo on the Enthusiast’s wrist. What so many Grey-worlders didn’t seem to grasp was that a spell was only as strong as the person casting it. How strong was this one?

A smiled tugged at the corner of Kell’s lips as he nudged the game box in the man’s direction. “Know what that is?”

Ned lifted the child’s game gingerly, as if it might burst into flames at any moment (Kell briefly considered igniting it, but restrained himself). He fiddled with the box until his fingers found the clasp and the board fell open on the counter. The elements glittered in the flickering pub light.

“Tell you what,” said Kell. “Choose one element. Move it from its notch—without touching it, of course—and I’ll bring you your dirt.”

Ned’s brow furrowed. He considered the options, then jabbed a finger at the water. “That one.”

At least he wasn’t fool enough to try for the bone, thought Kell. Air, earth, and water were the easiest to will—even Rhy, who showed no affinity whatsoever, could manage to rouse those. Fire was a bit trickier, but by far, the hardest piece to move was the bit of bone. And for good reason. Those who could move bones could move bodies. It was strong magic, even in Red London.

Kell watched as Ned’s hand hovered over the game board. He began to whisper to the water under his breath in a language that might have been Latin, or gibberish, but surely wasn’t the King’s English. Kell’s mouth quirked. Elements had no tongue, or rather, they could be spoken to in any. The words themselves were less important than the focus they brought to the speaker’s mind, the connection they helped to form, the power they tapped into. In short, the language did not matter, only the intention did. The Enthusiast could have spoken to the water in plain English (for all the good it would do him) and yet he muttered on in his invented language. And as he did, he moved his hand clockwise over the small board.

Kell sighed, and propped his elbow on the counter and rested his head on his hand while Ned struggled, face turning red from the effort.

After several long moments, the water gave a single ripple (it could have been caused by Kell yawning or the man gripping the counter) and then went still.

Ned stared down at the board, veins bulging. His hand closed into a fist, and for a moment Kell worried he’d smash the little game, but his knuckles came down beside it, hard.

“Oh well,” said Kell.

“It’s rigged,” growled Ned.

Kell lifted his head from his hand. “Is it?” he asked. He flexed his fingers a fraction, and the clod of earth rose from its groove and drifted casually into his palm. “Are you certain?” he added as a small gust caught up the sand and swirled it into the air, circling his wrist. “Maybe it is”—the water drew itself up into a drop and then turned to ice in his palm—“or maybe it’s not. …” he added as the oil caught fire in its groove.

“Maybe …” said Kell as the piece of bone rose into the air, “… you simply lack any semblance of power.”

Ned gaped at him as the five elements each performed their own small dance around Kell’s fingers. He could hear Rhy’s chiding: Show-off. And then, as casually as he’d willed the pieces up, he let them fall. The earth and ice hit their grooves with a thud and a clink while the sand settled soundlessly in its bowl and the flame dancing on the oil died. Only the bone was left, hovering in the air between them. Kell considered it, all the while feeling the weight of the Enthusiast’s hungry gaze.

“How much for it?” he demanded.

“Not for sale,” answered Kell, then corrected himself, “Not for you.”

Ned shoved up from his stool and turned to go, but Kell wasn’t done with him yet.

“If I brought you your dirt,” he said, “what would you give me for it?”

He watched the Enthusiast freeze in his steps. “Name your price.”

“My price?” Kell didn’t smuggle trinkets between worlds for the money. Money changed. What would he do with shillings in Red London? And pounds? He’d have better luck burning them than trying to buy anything with them in the White alleys. He supposed he could spend the money here, but what ever would he spend it on? No, Kell was playing a different game. “I don’t want your money,” he said. “I want something that matters. Something you don’t want to lose.”

Ned nodded hastily. “Fine. Stay here and I’ll—”

“Not tonight,” said Kell.

“Then when?”

Kell shrugged. “Within the month.”

“You expect me to sit here and wait?”

“I don’t expect you to do anything,” said Kell with a shrug. It was cruel, he knew, but he wanted to see how far the Enthusiast was willing to go. And if his resolve held firm and he were here next month, decided Kell, he would bring the man his bag of earth. “Run along now.”

Ned’s mouth opened and closed, and then he huffed, and trudged off, nearly knocking into a small, bespectacled man on his way out.

Kell plucked the bit of bone out of the air and returned it to its box as the bespectacled man approached the now-vacant stool.

“What was that about?” he asked, taking the seat.

“Nothing of bother,” said Kell.

“Is that for me?” asked the man, nodding at the game box.

Kell nodded and offered it to the Collector, who lifted it gingerly from his hand. He let the gentleman fiddle with it, then proceeded to show him how it worked. The Collector’s eyes widened. “Splendid, splendid.”

And then the man dug into his pocket and withdrew a folded kerchief. It made a thud when he set it on the counter. Kell reached out and unwrapped the parcel to find a glimmering silver box with a miniature crank on the side.

A music box. Kell smiled to himself.

They had music in Red London, and music boxes, too, but most of theirs played by enchantment, not cog, and Kell was rather taken by the effort that went into the little machines. So much of the Grey world was clunky, but now and then its lack of magic led to ingenuity. Take its music boxes. A complex but elegant design. So many parts, so much work, all to create a little tune.

“Do you need me to explain it to you?” asked the Collector.

Kell shook his head. “No,” he said softly. “I have several.”

The man’s brow knit. “Will it still do?”

Kell nodded and began to fold the kerchief over the trinket to keep it safe.

“Don’t you want to hear it?”

Kell did, but not here in the dingy little tavern, where the sound could not be savored. Besides, it was time to go home.

He left the Collector at the counter, tinkering with the child’s game—marveling at the way that neither the melted ice nor the sand spilled out of their grooves, no matter how he shook the box—and stepped out into the night. Kell made his way toward the Thames, listening to the sounds of the city around him, the nearby carriages and faraway cries, some in pleasure, some in pain (though they were still nothing compared to the screams that carried through White London). The river soon came into sight, a streak of black in the night as church bells rang out in the distance, eight of them in all.

Time to go.

He reached the brick wall of a shop that faced the water, and stopped in its shadow, pushing up his sleeve. His arm had started to ache from the first two cuts, but he drew out his knife and carved a third, touching his fingers first to the blood and then to the wall.

One of the cords around his throat held a red lin, like the one King George had returned to him that afternoon, and he took hold of the coin and pressed it to the blood on the bricks.

“Well, then,” he said. “Let’s go home.” He often found himself speaking to the magic. Not commanding, simply conversing. Magic was a living thing—that, everyone knew—but to Kell it felt like more, like a friend, like family. It was, after all, a part of him (much more than it was a part of most) and he couldn’t help feeling like it knew what he was saying, what he was feeling, not only when he summoned it, but always, in every heartbeat and every breath.

He was, after all, Antari.

And Antari could speak to blood. To life. To magic itself. The first and final element, the one that lived in all and was of none.

He could feel the magic stir against his palm, the brick wall warming and cooling at the same time with it, and Kell hesitated, waiting to see if it would answer without being asked. But it held, waiting for him to give voice to his command. Elemental magic may speak any tongue, but Antari magic—true magic, blood magic—spoke one, and only one. Kell flexed his fingers on the wall.

“As Travars,” he said. Travel.

This time, the magic listened, and obeyed. The world rippled, and Kell stepped forward through the door and into darkness, shrugging off Grey London like a coat.

II

RED ROYAL

I

“Sanct!” announced Gen, throwing a card down onto the pile, faceup. On its front, a hooded figure with a bowed head held up a rune like a chalice, and in his chair, Gen grinned triumphantly.

Parrish grimaced and threw his remaining cards facedown on the table. He could accuse Gen of cheating, but there was no point. Parrish himself had been cheating for the better part of an hour and still hadn’t won a single hand. He grumbled as he shoved his coins across the narrow table to the other guard’s towering pile. Gen gathered up the winnings and began to shuffle the deck. “Shall we go again?” he asked.

“I’ll pass,” answered Parrish, shoving to his feet. A cloak—heavy panels of red and gold fanning like rays of sun—spilled over his armored shoulders as he stood, the layered metal plates of his chest piece and leg guards clanking as they slid into place.

“Ir chas era,” said Gen, sliding from Royal into Arnesian. The common tongue.

“I’m not bitter,” grumbled Parrish back. “I’m broke.”

“Come on,” goaded Gen. “Third time’s the charm.”

“I have to piss,” said Parrish, readjusting his short sword.

“Then go piss.”

Parrish hesitated, surveying the hall for signs of trouble. The hall was devoid of trouble—or any other forms of activity—but full of pretty things: royal portraits, trophies, tables (like the one they’d been playing on), and, at the hall’s end, a pair of ornate doors. Made of cherrywood, the doors were carved with the royal emblem of Arnes, the chalice and rising sun, the grooves filled with melted gold, and above the emblem, the threads of metallic light traced an R across the polished wood.

The doors led to Prince Rhy’s private chambers, and Gen and Parrish, as part of Prince Rhy’s private guard, had been stationed outside of them.

Parrish was fond of the prince. He was spoiled, of course, but so was every royal—or so Parrish assumed, having served only the one—but he was also good-natured and exceedingly lenient when it came to his guard (hell, he’d given Parrish the deck of cards himself, beautiful, gilded-edge things) and sometimes, after a night of drinking, would shed his Royal and its pretentions and converse with them in the common tongue (his Arnesian was flawless). If anything, Rhy seemed to feel guilty for the persistent presence of the guards, as if surely they had something better to do with their time than stand outside his door and be vigilant (and in truth, most nights it was more a matter of discretion than vigilance).

The best nights were the ones when Prince Rhy and Master Kell set out into the city, and he and Gen were allowed to follow at a distance or relieved of their duties entirely and allowed to stay for company rather than protection (everyone knew that Kell could keep the prince safer than any of his guard). But Kell was still away—a fact that had put the ever-restless Rhy in a mood—and so the prince had withdrawn early to his chambers, and Parrish and Gen had taken up their watch, and Gen had robbed Parrish most of his pocket money.

Parrish scooped up his helmet from the table, and went to relieve himself; the sound of Gen counting his coins followed him out. Parrish took his time, feeling he was owed as much after losing so many lin, and when he finally ambled back to the prince’s hall, he was distressed to find it empty. Gen was nowhere to be seen. Parrish frowned; leniency went only so far. Gambling was one thing, but if the prince’s chambers were caught unguarded, their captain would be furious.

The cards were still on the table, and Parrish began to clean them up when he heard a male voice in the prince’s chamber and stopped. It was not a strange thing to hear, in and of itself—Rhy was prone to entertaining and made little secret of his varied tastes, and it was hardly Parrish’s place to question his proclivities.

But Parrish recognized the voice at once; it did not belong to one of Rhy’s pursuits. The words were English, but accented, the edges rougher than an Arnesian tongue.

It was a voice like a shadow in the woods at night. Quiet and dark and cold.

And it belonged to Holland. The Antari from afar.

Parrish paled a little. He worshipped Master Kell—a fact Gen gave him grief for daily—but Holland terrified him. He didn’t know if it was the evenness in the man’s tone or his strangely faded appearance or his haunted eyes—one black, of course, the other a milky green. Or perhaps it was the way he seemed to be made more of water and stone than flesh and blood and soul. Whatever it was, the foreign Antari had always given Parrish the shivers.

Some of the guards called him Hollow behind his back, but Parrish never dared.

“What?” Gen would tease. “Not like he can hear you through the wall between worlds.”

“You don’t know,” Parrish would whisper back. “Maybe he can.”

And now Holland was in Rhy’s room. Was he supposed to be there? Who had let him in?

Where was Gen? wondered Parrish as he took up his spot in front of the door. He didn’t mean to eavesdrop, but there was a narrow gap between the left side of the door and the right, and when he turned his head slightly, the conversation reached him through the crack.

“Pardon my intrusion,” came Holland’s voice, steady and low.

“It’s none at all,” answered Rhy casually. “But what business brings you to me instead of to my father?”

“I have been to your father for business already,” said Holland. “I come to you for something else.”

Parrish’s cheeks reddened at the seductiveness in Holland’s tone. Perhaps it would be better to abandon his post than listen in, but he held his ground, and heard Rhy slump back onto a cushioned seat.

“And what’s that?” asked the prince, mirroring the flirtation.

“It is nearly your birthday, is it not?”

“It is nearly,” answered Rhy. “You should attend the celebrations, if your king and queen will spare you.”

“They will not, I fear,” replied Holland. “But my king and queen are the reason I’ve come. They’ve bid me deliver a gift.”

Parrish could hear Rhy hesitate. “Holland,” he said, the sound of cushions shifting as he sat forward, “you know the laws. I cannot take—”

“I know the laws, young prince,” soothed Holland. “As to the gift, I picked it out here, in your own city, on my masters’ behalf.”

There was a long pause, followed by the sound of Rhy standing. “Very well,” he said.

Parrish heard the shuffle of a parcel being passed and opened.

“What is it for?” asked the prince after another stretch of quiet.

Holland made a sound, something between a smile and a laugh, neither of which Parrish had borne witness to before. “For strength,” he said.

Rhy began to say something else, but at the same instant, a set of clocks went off through the palace, marking the hour and masking whatever else was said between the Antari and the prince. The bells were still echoing through the hall when the door opened and Holland stepped out, his two-toned eyes landing instantly on Parrish.

Holland guided the door shut and considered the royal guard with a resigned sigh. He ran a hand through his charcoal hair.

“Send away one guard,” he said, half to himself, “and another takes his place.”

Before Parrish could think of a response, the Antari dug a coin from his pocket and flicked it into the air toward him.

“I wasn’t here,” said Holland as the coin rose and fell. And by the time it hit Parrish’s palm, he was alone in the hall, staring down at the disk, wondering how it got there, and certain he was forgetting something. He clutched the coin as if he could catch the slipping memory, and hold on.

But it was already gone.

II

Even at night, the river shone red.

As Kell stepped from the bank of one London onto the bank of another, the black slick of the Thames was replaced by the warm, steady glow of the Isle. It glittered like a jewel, lit from within, a ribbon of constant light unraveling through Red London. A source.

A vein of power. An artery.

Some thought magic came from the mind, others the soul, or the heart, or the will.

But Kell knew it came from the blood.

Blood was magic made manifest. There it thrived. And there it poisoned. Kell had seen what happened when power warred with the body, watched it darken in the veins of corrupted men, turning their blood from crimson to black. If red was the color of magic in balance—of harmony between power and humanity—then black was the color of magic without balance, without order, without restraint.

As an Antari, Kell was made of both, balance and chaos; the blood in his veins, like the Isle of Red London, ran a shimmering, healthy crimson, while his right eye was the color of spilled ink, a glistening black.

He wanted to believe that his strength came from his blood alone, but he could not ignore the signature of dark magic that marred his face. It gazed back at him from every looking glass and every pair of ordinary eyes as they widened in awe or fear. It hummed in his skull whenever he summoned power.

But his blood never darkened. It ran true and red. Just as the Isle did.

Arcing over the river, in a bridge of glass and bronze and stone, stretched the royal palace. It was known as the Soner Rast. The “Beating Heart” of the city. Its curved spires glittered like beads of light.

People flocked to the river palace day and night, some to bring cases to the king or queen, but many simply to be near the Isle that ran beneath. Scholars came to the river’s edge to study the source, and magicians came hoping to tap into its strength, while visitors from the Arnesian countryside only wanted to gaze upon the palace and river alike, and to lay flowers—from lilies to shooting stars, azaleas to moondrops—all along the bank.

Kell lingered in the shadow of a shop across the road from the riverside and looked up at the palace, like a sun caught in constant rise over the city, and for a moment, he saw it the way visitors must. With wonder.

And then a flicker of pain ran through his arm, and he came back to his senses. He winced, slipped the traveling coin back around his neck, and made his way toward the Isle, the banks of the river teeming with life.

The Night Market was in full swing.

Vendors in colored tents sold wares by the light of river and lantern and moon, some food and others trinkets, the magic and mundane alike, to locals and to pilgrims. A young woman held a bushel of starflowers for visitors to set on the palace steps. An old man displayed dozens of necklaces on a raised arm, each adorned with a burnished pebble, tokens said to amplify control over an element.

The subtle scent of flowers was lost beneath the aroma of cooking meat and freshly cut fruit, heavy spices and mulled wine. A man in dark robes offered candied plums beside a woman selling scrying stones. A vendor poured steaming tea into short glass goblets across from another vibrant stall displaying masks and a third offering tiny vials of water drawn from the Isle, the contents still glowing faintly with its light. Every night of the year, the market lived and breathed and thrived. The stalls were always changing, but the energy remained, as much a part of the city as the river it fed on. Kell traced the edge of the bank, weaving through the evening fair, savoring the taste and smell of the air, the sound of laughter and music, the thrum of magic.

A street mage was doing fire tricks for a cluster of children, and when the flames burst up from his cupped hands into the shape of a dragon, a small boy stumbled back in surprise and fell right into Kell’s path. He caught the boy’s sleeve before he hit the street stones, and hoisted him to his feet.

The boy was halfway through mumbling a thankyousirsorry when he looked up and caught sight of Kell’s black eye beneath his hair, and the boy’s own eyes—both light brown—went wide.

“Mathieu,” scolded a woman as the boy tore free of Kell’s hand and fled behind her cloak.

“Sorry, sir,” she said in Arnesian, shaking her head. “I don’t know what’s gotten—”

And then she saw Kell’s face, and the words died. She had the decency not to turn and flee like her son, but what she did was much worse. The woman bowed in the street so deeply that Kell thought she would fall over.

“Aven, Kell,” she said, breathless.

His stomach twisted, and he reached for her arm, hoping to make her straighten before anyone else could see the gesture, but he was only halfway to her, and already too late.

“He was … not l-looking,” she stammered, struggling to find the words in English, the royal tongue. It only made Kell cringe more.

“It was my fault,” he said gently in Arnesian, taking her elbow and urging her up out of the bow.

“He just … he just … he did not recognize you,” she said, clearly grateful to be speaking the common tongue. “Dressed as you are.”

Kell looked down at himself. He was still wearing the brown and fraying coat from the Stone’s Throw, as opposed to his uniform. He hadn’t forgotten; he’d simply wanted to enjoy the fair, just for a few minutes, as one of the pilgrims or locals. But the ruse was at an end. He could feel the news ripple through the crowd, the mood shifting like a tide as the patrons of the Night Market realized who was among them.

By the time he let go of the woman’s arm, the crowd was parting for him, the laughter and shouting reduced to reverent whispers. Rhy knew how to deal with these moments, how to twist them, how to own them.

Kell wanted only to disappear.

He tried to smile, but knew it must look like a grimace, so he bid the woman and her son good night, and made his way quickly down the river’s edge, the murmurings of the vendors and patrons trailing him as he went. He didn’t look back, but the voices followed all the way to the flower-strewn steps of the royal palace.