6,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

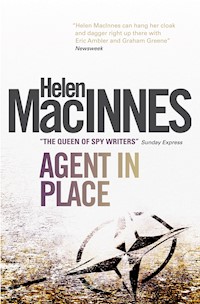

Chuck Kelso is an idealist. When he steals a top-secret NATO memorandum, he only intends to leak it to the press; but it is soon in the hands of a Russian agent, a man who has spent nine years quietly working himself into the fabric of Washington society. Within hours it has reached the KGB, and the CIA's top man in Moscow has had his cover blown. For British agent Tony Lawton, hunting down the Russian operative - the 'agent in place' - is a welcome challenge. But for Chuck's brother, the journalist Tom Kelso, and his beautiful wife, Thea, the affair has unleashed a very special terror. Now the race is on to find the Russian spy before a top-level NATO conference. But why is the escaped agent behaving so strangely? Is he who he seems?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

ALSO BY HELEN MacINNES

AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Pray for a Brave Heart

Above Suspicion

Assignment in Brittany

North From Rome

Decision at Delphi

The Venetian Affair

The Salzburg Connection

Message From Málaga

While We Still Live

The Double Image

Neither Five Nor Three

Horizon

Snare of the Hunter

Agent in Place

Print edition ISBN: 9781781163351

E-book edition ISBN: 9781781164303

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: December 2012

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

© 1976, 2012 by the Estate of Helen MacInnes. All rights reserved.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book?

We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at:

[email protected] or write to us at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website.

www.titanbooks.com

To Ian Douglas Highet and Eliot Chace Highet,

with all my love

Helen MacInnes

If hopes were dupes, fears may be liars

ARTHUR HUGH CLOUGH

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

About the Author

1

The message had come at eight o’clock that morning as he was swallowing a first cup of black coffee to clear his head and open his eyes. But before he could cross over the short stretch of floor between him and the telephone, the ringing stopped. He started back to the kitchen, had barely reached its door before he halted abruptly. The telephone rang again. Twice. And stopped ringing. He glanced at the kitchen clock. He would have one minute exactly before the third call. Now fully alert, he pulled the pan of bacon and eggs away from the heat, did not even waste another moment to turn off the electric stove, moved at double time back into the living-room, reached the telephone on his desk, sat down with a pencil in his hand and a scrap of paper before him, and was ready. The message would be in code and he had better make sure of each digit. It had been a long long time since he had been summoned in this way. An emergency? He controlled his excitement, smothered all his wondering. Punctual to the second, the telephone rang again. Quickly he picked up the receiver. “Hello,” he said—slow, casual, indifferent.

“Hello, hello, hello there.” Two small coughs, a clearing of the throat.

He knew the voice at once. Nine years since he had last heard it, but its pattern was definite: deep, full-chested, slightly husky, the kind of voice that might break into an aria from Prince Igor or Boris Godounov with each of its notes almost a chord in itself. Mischa? Yes, Mischa. Even the initial greeting was his own sign-in phrase. Nine years since last heard, but still completely Mischa, down to the two coughs and the throat-clearing.

“Yorktown Cleaners?” Mischa was saying. “Please have my blue suit ready for delivery to 10 Old Park Place by six o’clock this evening. Receipt number is 69105A. And my name—” Slowing up of this last phrase gave the cue for a cut-in.

“Sorry—you’ve got the wrong number.”

“Wrong number?” High indignation. “The receipt is here in my hand. 69105A.”

“Wrong telephone number.” Heavy patience.

“What?” The tone was now aggressive, almost accusing. Very true to life was Mischa. “Are you sure?”

“Yes!” The one-word answer was enough to let Mischa know that his prize protégé Alexis had got the message.

“Let me check—” There was a brief pause while a dogged disbeliever riffled through a couple of pages against the background noise of muted street traffic. Then Mischa spoke again from his public telephone booth, this time with sharp annoyance, “Okay, okay.” Angrily, he banged down the receiver for an added touch of humour. He had always prided himself on his keen perception of Americans’ behaviour patterns.

For a moment, there was complete silence in the little apartment. Mischa, Mischa... Eleven years since he first started training me, Alexis was thinking, and nine years since I last saw him. He was a major then—Major Vladimir Konov. What now? A full-fledged colonel in the KGB? Even higher? With another name too, no doubt: several other names, possibly, in that long and hidden career. And here I am, still using the cover-name Mischa gave me, still stuck in the role he assigned me in Washington. But, as Mischa used to misquote with a sardonic smile, “They also serve who only sit and wait.”

Alexis recovered from his delayed shock as he noticed the sunlight shafting its way into his room from a break in the row of small Georgetown houses across the narrow street. The morning had begun; a heavy day lay ahead. He moved quickly now, preparing himself for it.

From the bookcase wall he picked out the second volume of Spengler’s Untergang des Abendlandes—the German text scared off Alexis’s American friends: they preferred it translated into The Decline of the West, even if the change into English lost the full meaning of the title. It ought to have been The Decline and Fall of the West, which might have made them think harder into the meaning of the book. With Spengler in one hand and his precious slip of paper in the other, Alexis left the sun-streaked living-room for the colder light of his dismal little kitchen. He was still wearing pyjamas and foulard dressing-gown, but even if cold clear November skies were outside the high window, he felt hot with mounting excitement. He pushed aside orange-juice and coffee-cup, tossed the Washington Post on to a counter-top, turned off the electric stove, and sat down at the small table crushed into one corner where no prying neighbours’ eyes could see him, even if their kitchens practically rubbed sinks with his.

Now, he thought, opening the Spengler and searching for a loose sheet of paper inserted in its second chapter (Origin and Landscape: Group of Higher Cultures), now for Mischa’s message. He had understood most of it, even at nine years’ distance, but he had to be absolutely accurate. He found the loose sheet, covered with his own compressed shorthand, giving him the key to the quick scrawls he had made on the scrap of paper from his desk. He began decoding. It was all very simple—Mischa’s way of thumbing his nose at the elaborate cleverness of the Americans, with their reliance on computers and technology. (Nothing, Mischa used to say and obviously still did, nothing is going to replace the well-trained agent, well-placed, well-directed. That the man had to be bright and dedicated was something that Mischa made quite sure of, before any time was wasted in training.)

Simple, Alexis thought again as he looked at the message, but effective in all its sweet innocence. “Yorktown” was New York, of course. The “blue suit” was Alexis in person. “10” meant nothing—a number that was used for padding. “Old Park Place” obviously meant the old meeting-place in the Park in New York—Central Park, as the receipt number “69105A” indicated: cancel the 10, leaving 69 for Sixty-ninth Street, 5A for Fifth Avenue.

The delivery time of the blue suit, “six o’clock” this evening, meant six hours minus one hour and twenty minutes.

So there I’ll be, thought Alexis, strolling by the old rendezvous just inside Central Park at twenty minutes of five this evening.

He burned the scrap of notes, replaced the sheet of paper in its nesting place, and put Spengler carefully back on the shelf. Only after that did he reheat the coffee, gulp down the orange-juice, look at the still-life of congealed bacon and eggs with a shudder, and empty the greasy half-cooked mess into the garbage-can. He would tidy up on Monday—the worst thing on this job was the chores you had to do yourself: dangerous to hand out duplicate keys to anyone coming in to scrub and dust. When things got beyond him in this small apartment, he’d call for untalkative Beulah, flat feet and arthritis, too stupid to question why he asked here to clean on a day he worked at home. Now he had better shave, shower and dress. And then do some telephoning of his own: to Sandra here in Washington, begging off her swinging party tonight; to Katie in New York, letting her know that he’d be spending the week-end again at her place. And he had better take the first Metroliner possible. Or the shuttle flight? In any case, he must make sure that he would reach New York with plenty of time to spare before the meeting with Mischa.

As he came out of the shower, he was smiling broadly at a sudden memory. Imagine, he thought, just imagine Mischa remembering that old fixation of mine on a blue suit, my idea of bourgeois respectability for my grand entry into the capitalist world. I was given it, too: an ill-fitting jacket of hard serge, turning purple with age, threads whitening at the seams, the seat of the pants glossed like a mirror, a rent here, some mud there; a very convincing picture of the refugee who had managed at last to outwit the Berlin Wall. (Mischa’s sense of humour, a scarce commodity in his line of business, was as strong as his cold assessment of Western minds: the pathetic image always works, he had said.) And now I have $22,000 a year and a job in Washington, and a three-room apartment one flight up in a Georgetown house, and a closet packed with clothes. Eight suits hanging there, but not a blue one among them. He laughed, shook his head, and began planning his day in New York.”

* * *

He arrived at Penn Station with almost three hours to spare, a time to lose himself in city crowds once he had dropped his small bag at Katie’s East Side apartment. That was easily done; Katie’s place had a self-service apartment and no doorman, and he had the keys to let him into both the entrance-hall and her fifth-floor apartment. It was a fairly old building as New York went, and modest in size—ten floors, with only space enough for two apartments on each of them. The tenants paid no attention to anyone, strangers all, intent on their own troubles and pleasures. They never even noticed him on his frequent week-end visits, probably assumed he was a tenant himself. But best of all was the location of the apartment-house between two busy avenues, one travelling north, the other south, buses and plenty of taxis.

Katie herself was a gem. Made to order, and no pun intended. She was out now, as he had expected: a restless type, devoted to causes and demonstrations. She had left a note for him in her pretty-girl scrawl. Chuck tried to reach you in Washington. Call him any time after five. Don’t forget party at Bo’s tonight. You are re-invited. See you here at seven? Kate. Bo Browning’s party...well, that was something better avoided. Danger for him there, in all that glib talk from eager Marxists who hadn’t even read Das Kapital all the way through. It was hard to keep himself from proving how little they knew, or how much he could teach them.

But Chuck—now that was something else again. There was urgency in his message. Could Chuck really be delivering? Last week-end he had been arguing himself into and out of a final decision. Better not count on anything, Alexis warned himself, and tried to repress a surge of hope, a flush of triumph. But his sudden euphoria stayed with him as he set off for Fifth Avenue and an hour or so in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

By four o’clock he began to worry about his timing, and came hurrying away from the Greek gods’ department, down the Museum’s giant flight of steps, his arm signalling to a loitering taxi. It would take him south, well past Sixty-ninth Street, all the way to the Central Park Zoo. He would use that entrance, wander around the zoo itself to put in fifteen minutes (he was going to be too early for Mischa after all). Now he was thinking only of the meeting ahead of him. The initial excitement was gone, replaced by nervousness, even a touch of fear. It was a special encounter, no doubt about that: there was something vital at stake. Had he made some error, was his judgment being distrusted? Had his growing boredom with those quiet nine years shown in his steady reports? But they were good reports, succinct, exact, giving the foibles and weaknesses of the hundreds of acquaintances and friends he had made in government and newspaper circles. As a member of Representative Pickering’s personal staff, with nine years of promotions all the way from secretarial adviser to office-manager controlling an office swollen to forty-seven employees, and now to the top job of communications director, he had contacts in every major office in government. He was invited around, kept an ear open for all rumours and indiscreet talk. There was plenty of that in Washington, some of it so careless that it baffled him. Americans were smart—a considerable enemy and one that posed a constant danger—that was what had been dinned into him in his long months of training; but after nine years in Washington, he had his doubts. What made clever Americans so damned stupid once they got into places of power?

The fifteen minutes were up, leaving him seven to walk northward through the Park to its Sixty-ninth Street area. Had he cut the time too short, after all? He increased his pace as he left the desolate zoo with its empty cages—animals were now kept mostly inside—and its trees bare-branched with first frosts. The Saturday crowd was leaving too, moving away from the gathering shadows. So he wasn’t noticeable. And he hadn’t been followed. He never was. But he was suddenly surprised out of his self-preoccupation by the dimming sky. The bright clear blue of the afternoon had faded. It would soon be dusk. The street lights were already on; so were the lamps posted along the paths, little bursts of brightness surrounded by darkening meadows, by bushes and trees that formed black blots over falling and rising ground. Fifth Avenue lay to his right beyond the wall that edged the Park. Traffic was brisk, audible but not visible; only the high-rising apartment buildings, lining the other side of the avenue, could be seen. Their windows—expensive curtains undrawn, shades left unpulled—were ablaze with light. What was this about an energy crisis?

Strange, he thought as he came through a small underpass, how isolated this park can make you feel; almost as if you were on a lonely country road. The crowd had thinned, easing off in other directions. He was alone, and approaching a second underpass as the path sloped downward, edging away from the Fifth Avenue wall. Now it was almost dusk, the sky washed into the colour of faded ink tinged with a band of apricot above the far-off black silhouettes of Central Park West.

The underpass looked as grim as a tunnel—a short one, fortunately. Near its entrance, on the small hillside of bushes and rocks that lay on his right, he saw a group of four men. No, just boys: two leaning against a crag, nonchalant, thin; two squatting on the slope of grass, knees up to their black chins: all of them watching. He noticed the sneakers on their feet. Keep walking and get ready to sprint, he told himself. And then his fear doubled as he heard lightly-running footsteps behind him. He swung round to face the new threat. But it was only a couple of joggers, dressed in track suits, having their evening run. “Hi!” he said in relief as the joggers neared him rapidly.

“Hi!” one said, pink-faced and frowning. He glanced at the hill. Both he and his friend slowed their pace but didn’t stop. “Like to join us?” the other one asked, thin-faced and smiling.

And he did, breaking into their rhythm as he unbuttoned his topcoat, jogging in unison. Through the underpass, then up the path as it rose in a long steady stretch. “Race you to the top,” the thin-faced man said. But up there, where the outcrop of Manhattan rocks rose into a cluster of crags, he would be almost in sight of the Sixty-ninth Street entrance. Now was the time to break off, although he could have given them a good run for their money.

He smiled, pretended to have lost his wind, stopped half-way up the path, gave them a wave of thanks. With an answering wave they left him, and without a word increased their pace to a steady run. Amazing how quickly they could streak up that long stretch of hill; but they had earned this demonstration of their superiority, and he was too thankful to begrudge them their small triumph. He was willing to bet, though, that once they were out of sight, they’d slacken their pace back to a very easy jog. What were they, he wondered—a lawyer, an accountant? Illustrators or advertising men? They looked the type, lived near by, and exercised in the evening before they went home to their double vodka Martinis.

He finished the climb at a brisk pace. Far behind him, the four thin loose-limbed figures had come through the underpass and halted, as if admitting that even their sneakers couldn’t catch up on the distance between him and them. Ahead of him, there were a man walking two large dogs; another jogger; and the small flagpole that marked the convergence of four paths—the one he was following, the one that continued to the north, the one that led west across rolling meadows, the one that came in from the Sixty-ninth Street entrance. Thanks to his run, he was arriving in good time after all, with one minute to spare. He was a little too warm, a little dishevelled, but outwardly calm, and ready to face Mischa. He straightened his tie, smoothed his hair, decided to button his topcoat even if it was stifling him.

He might not have appeared so calm if he could have heard his lawyer-accountant-illustrator-advertising types. Once they had passed the flagpole on its little island of grass, they had dropped behind some bushes to cool off. It had been a hard pull up that hill.

“Strange guy. What the hell does he think he’s doing, walking alone at this time of day?” The red face faded back to its natural pink.

“Stranger in town.”

“Well dressed. In good training, I thought. Better than he pretended.”

“Wouldn’t have had much chance against four, though. What now, Jim? Continue patrol, or double back? See what that wolf-pack is up to?”

“Looking for some other lone idiot,” Jim said.

“Don’t complain. Think of the nice open-air job they give us.”

Jim stood up, flexed his legs. “On your feet, Burt. Better finish our rounds. Seems quiet enough here.” There were three other joggers—bona fide ones, these—plodding in from the west towards Sixty-ninth Street and home; a man walking two Great Danes; a tattered drunk slumped on the cold hard grass, clutching the usual brown paper bag; two sauntering women, with peroxide curls, tight coats over short skirts (chilly work, thought Jim, on a cool November night), high heels, swinging handbags. “Nothing but honest citizens,” Jim said with a grin. The wolf-pack had vanished, prowling for better prospects.

“Here’s another idiot,” said Burt in disgust as he and Jim resumed their patrol northward. The lone figure walking towards them, down the path that led from the Seventy-second Street entrance, was heavily dressed and solidly built, but he moved nimbly, swinging his cane, his snap-brim tilted to one side. He paid no attention to them, apparently more interested in the Fifth Avenue skyline, so that the droop of his hat and the turned head gave only a limited view of his profile. He seemed confident enough. “At least he carries a hefty stick. He’ll be out of the park in no time, anyway.”

“If he doesn’t go winging his way down to the zoo,” Jim said. He frowned, suddenly veered away to his left, halting briefly by a tree, just far enough to give him a view of the flagpole where the four paths met. Almost at once he came streaking back, the grass silencing his running-shoes, the grey of his tracksuit blending into the spreading shadows. “He won’t be alone,” he reported as he rejoined Burt. “So he’ll be safe enough.” Two idiots were safer than one.

“So that’s their hang-up, is it? We’ll leave them to the Vice boys. They’ll be around soon.” Dusk would end in another half-hour, and darkness would be complete. The two men jogged on in silence, steps in unison, rhythm steady, eyes alert.

2

They arrived at the flagpole almost simultaneously. “Well timed,” said Mischa and nodded his welcome. There was no handclasp, no outward sign of recognition. “You look well. Bourgeois life agrees with you. Shall we walk a little?” His eyes had already swept over the drunk lolling on the grass near the Sixty-ninth Street entrance. He glanced back, for a second look at the two women with the over-made-up faces and ridiculous clothes, who were now sitting on a bench beside the lamp-post. One saw him, rose expectantly, adjusted her hair. Mischa turned away, now sizing up a group of five people—young, thin, long-haired, two of them possibly girls, all wearing tight jeans and faded army jackets—who had come pouring in from Fifth Avenue. But they saw no one, heard nothing; they headed purposefully for the near-by clusters of rocks and crags and their own private spot. Mischa’s eyes continued their assessment and chose the empty path that led westward across the park. His cane gestured. “Less interruption here, I think. And if no one is already occupying those trees just ahead, we should have a nice place to talk.”

And a good view of anyone approaching, Alexis thought as they reached two trees, just off the road, and stepped close to them. The bushes around them had been cleared, so even a rear attack could be seen in time. Suddenly he realised that Mischa wasn’t even thinking about an ambush by muggers at four forty-five in the evening—he probably assumed that ten o’clock or midnight were the criminal hours. All Mischa’s caution was being directed against his old adversaries. “Central Park has changed a lot since you were last here,” Alexis said tactfully. This was a hell of a place to have a meeting, but how was he to suggest that? “In summer, of course, it’s different. More normal people around. Concerts, plays—”

“A lot has changed,” Mischa cut him off. “But not in our work.” His face broke into a wide grin, showing a splendid set of teeth. His clever grey eyes crinkled as he studied the younger man, his hat thumbed back to show a wide brow and a bristle of greying hair. With rounded chin and snub nose, he had looked nine years ago—although it would be scarcely diplomatic now to mention the name of a non-person—very much like a younger version of Nikita Khrushchev. But nine years ago Mischa had had slight gaps between his front teeth. The grin vanished. “There is no détente in Intelligence. And don’t you ever forget that.” A forefinger jabbed against Alexis’s chest to emphasise the last five words. Then a strong hand slapped three affectionate blows on Alexis’s shoulders, and the voice was back to normal. “You look like an American, you talk like an American, but you must never think like an American.” The smile was in place again.

Mischa broke into Russian, perhaps to speak faster and make sure of his meaning. “You’ve done very well. I congratulate you. I take it, by the way you walked up so confidently to meet me, that no one was following you?”

The small reprimand had been administered deftly. In that, Mischa hadn’t changed at all. But in other ways, yes. Mischa’s old sense of humour, for instance. Tonight he was grimly serious even when he smiled. He’s a worried man, thought Alexis. “No, no one tailed me.” Alexis’s lips were tight. “But what about you?” He nodded to a solitary figure, husky and fairly tall, who had walked along the path on the heels of two men with a Doberman, and now was retracing his steps. Again he didn’t glance in their direction, just kept walking at a steady pace.

“You are nervous tonight, Alexis. Why? That is only my driver. Did you expect me to cope with New York traffic on a Saturday night? Relax, relax. He will patrol this area very efficiently.”

“Then you are expecting some interest—” Alexis began.

“Hardly. I am not here yet.”

Alexis stared.

“Officially I arrive next Tuesday, attached to a visiting delegation concerned with agricultural problems. We shall be in Washington for ten days. You are bound to hear of us, probably even meet us at one of those parties you attend so zealously. Of course I shall have more hair, and it will be darker.”

“I won’t flicker an eyelash.” As I might have done, Alexis admitted to himself: you did not live in a Moscow apartment for six months, completely isolated from other trainees, with only Mischa as your visitor and tutor, and not recognise him when you met him face to face in some Senator’s house. But Mischa had not slipped into America ahead of his delegation, and planned a secret meeting in Central Park, merely to warn Alexis about a Washington encounter. What was so important that it could bring them together like this? “So now you are an expert on food-grains,” Alexis probed.

“Now, now,” Mischa chided. “You may have been one of my best pupils, but you don’t have to try my own tricks on me.” He was amused. Briefly. “I’ve been following your progress. I have seen your reports, those that are of special interest. You have not mentioned Thomas Kelso in the last three months. No progress there? What about his brother, Charles Kelso—you are still his friend?”

“Yes.”

“Then why?”

“Because Chuck Kelso now lives in New York. Tom Kelso lives mostly in Washington.”

“But Charles Kelso did introduce you to his brother?”

“Yes.”

“Four years ago?”

“Yes.”

“And you have not established yourself with Thomas Kelso by this time?”

“I tried several visits on my own after Chuck left Washington. Polite reception. No more. I was just another friend of his brother—Chuck is ten years younger than Tom, and that makes a big difference in America.”

“Ridiculous. They are brothers. They were very close. That is why we instructed you to renew your friendship with Charles Kelso when you and he met again in Washington. Five years ago, wasn’t that?”

“Almost five.”

“And two years ago, when it was reported that Thomas Kelso needed a research assistant, you were instructed to suggest—in a friendly meeting—that you would be interested in that position. Your reaction to that order was negative. Why?”

“It was an impossible suggestion. Too dangerous. At present I am making $22,000 a year. Did you want me to drop $14,000 and rouse suspicions?”

“Was $8,000 a year all he could afford?” Mischa was disbelieving. “But he must make—”

“Not all Americans are millionaires,” said Alexis. “Isn’t that what you used to impress on me? Sure, Kelso is one of the best—and best-paid—reporters on international politics. He picks up some extra money from articles and lectures, plus travel expenses when he has an assignment abroad. But he lives on the income he earns. That is what keeps him a busy man, I suppose.”

“An influential man,” Mischa said softly. “What about that book he has been writing for the last two years?”

“Geopolitics. Deals with the conflict between the Soviet Union and China.”

“That much, we also know,” Mischa said in sharp annoyance. “Is that all you have learned about it?”

“It is all anyone has learned in Washington. Do you think he wants his ideas stolen?”

“You had better try again with Mr. Thomas Kelso, and keep on trying.”

“But what has this to do with your work in Directorate S?” That was the section of the First Chief Directorate that dealt in Illegals—agents with assumed identities sent to live abroad.

There was a moment of silence. It was impossible to see Mischa’s expression clearly now. Night had come, black and bleak. Alexis could feel the angry stare that was directed at him through the darkness, and regretted his temerity. He repressed a shiver, turned up his coat-collar. Then Mischa said, “The brash American,” and even laughed. He added, “It has to do with my present work, very much so.” He relented still further, and a touch of humour entered his voice. “Let us say that I am interested in influencing people who influence people.”

So Mischa had moved over to the First Chief Directorate’s Department A: Disinformation. Alexis was appropriately impressed, but he kept silent. He had already said too much. If Mischa wasn’t his friend, he might have been yanked out of Washington and sent to the Canal Zone or Alaska.

“So,” said Mischa, “you will persevere with Tom Kelso. He is important because of his job and the friends he makes through it—in Paris, Rome, London—and, of course, in the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation. They trust him there in NATO. He hears a great deal.”

Alexis nodded.

“About NATO...” Mischa was too casual, almost forgetful about what he had intended to say. “Oh yes,” he remembered; “you sent us a piece of information a few days ago about that top-security memorandum they passed to the Pentagon. You said it was now being studied at Shandon House.” He was being routinely curious, it seemed, his voice conversational.

“It is being analysed and evaluated. A double check on the Pentagon’s own evaluation.”

“What is the real function of this Shandon House? Oh, we know it is a collection of brains working with computers; but—super-secret? Capable of being trusted with such a memorandum?”

“It is trusted. Everyone has top clearance. Security is tight.”

“Ah, patriots all. Yet you said that it might be possible to breach that security. How? When?” The tone was still conversational.

“Soon. Perhaps even—” Alexis restrained himself. Better not be too confident. Better not be too precise. Then if the project turned sour, he wouldn’t be blamed for promising too much and achieving too little. “I have no guarantee. But there is a possibility,” he said more guardedly.

“When will you know more than that?”

“Perhaps later tonight.”

“Tonight!” Mischa exploded. “I knew you had something. I knew it by the way you worded your message!”

So it was his information on the NATO Memorandum that had brought Mischa chasing over to New York. He had read Alexis’s message last Tuesday or Wednesday. By Saturday he was here. In person. Was the memorandum so important as that?

“You are set to act?” Mischa demanded. “What is your plan?”

“I have three possible variants. It depends. But I’ll deliver.”

“You are using microfilm, of course? The memorandum is in three parts—over forty pages, I hear. You will need time.”

Another hazard, thought Alexis. “I’ll make time.”

“And when you deliver, do not employ your usual method.”

“No?” Alexis was puzzled. It was a set procedure. Any photographs he had taken, like his own reports in code, were passed to his weekly contact in Washington. The contact delivered them to Control, who in turn handed them over to the Residency. From there they were speeded to the Centre in Moscow. There had never been any slip-up. His contact had a gift for choosing casual encounters, all very natural.

“No! You will make the delivery to Oleg. He will alert you by telephone, and contact you some place of his own choosing. On Monday.”

“But I may not have the microfilm by Monday. It may be the following week-end before—”

“Then you deliver it to Oleg on the following week-end,” Mischa said impatiently. “You won’t have any chance to get the NATO Memorandum after that. It returns to the Pentagon, we hear, for finalised recommendations to the National Security Council. Before then, we want the particulars of that document. So press your advantage with Shandon House. You do your job, and Oleg will do his.”

“Oleg—how will I be able to identify him?” Surely not by a lot of mumbo-jumbo, Alexis thought in dismay: recognition signals wasted time, added to the tension. He had always felt safer in knowing his contact by sight, although there his interest stopped and he neither knew nor cared who the man was. The contact followed the same rules. To him, Alexis was a telephone number and a face.

Mischa raised his cane, pointed to their watchdog, who had stationed himself at a discreet distance.

“He isn’t near any lamp-post,” Alexis objected.

“You will see his face quite clearly as we pass him. Shall we go?” Mischa tilted his hat back in place. “We separate before we approach the flagpole area. I shall leave by way of the zoo. You head for the Seventy-second Street exit. Oleg takes Sixty-ninth Street—his car is parked there. He will drive down Fifth Avenue, and pick me up at the zoo. Simple and safe. It will raise no eyebrows. You agree?” Mischa moved away from the trees.

Alexis, with a quick glance over his shoulder—he had thought he saw two lurking shadows in the rough background—stepped on to the path. Mischa noticed. “Scared of the dark?” he asked with a laugh. “At half-past five in the evening? Alexis, Alexis...” He shook his head. They walked in silence towards the waiting man.

As they passed close to him, he was lighting a cigarette. The lighter didn’t flare. It glowed, with enough power to let Oleg’s face be clearly seen. The glow ended abruptly. The cigarette remained unlit.

“You’ll remember him?” Mischa asked.

“Yes. But could he see me clearly enough?”

“He has examined close-up photographs of your face. No trouble in quick identification. That’s what you like, isn’t it? I agree. No doubt, no uncertainties.” Behind them Oleg followed discreetly.

Some fifty yards away from the flagpole, Mischa said, “Now we leave each other. Take a warm handshake for granted.” This time the smile was genuine. “I shall hear from you soon?” It was more of a command than a question.

“Soon.” No other answer was possible. He had forgotten how inexorable and demanding Mischa could be.

Mischa nodded and left. Soon he had drawn well ahead. Alexis slowed his pace slightly, letting the distance between them increase. Oleg passed him, intent on reaching the car he had parked near by, possibly on Sixty-ninth Street itself. It was west-bound, of course: just the added touch to Mischa’s careful arrangements.

Alexis watched Mischa as he took the southward path at the flagpole. For a few moments a near-by lamp-post welcomed him into its wide circle of white light, showed clearly his solid figure and brisk stride against the background of massive rocks that filled this corner of the park. Then he was gone, swinging down towards the zoo.

Oleg was now well beyond the flagpole and heading for Fifth Avenue. Alexis noted for future reference the way he moved, the set of his shoulders, his height and breadth; the way he turned his head to look at the drunk, now sitting with his head between his knees. A dog-walker, enmeshed in a tangle of leashes, merited only a brief glance. One of the prostitutes still loitering under a lamp-post received no attention at all: virtuous fellow, this Oleg.

So now, thought Alexis with a smile when he reached the flagpole, it’s my turn to branch off. Two steps, and he stopped abruptly as he heard a shout. One shout. He looked round at the path to the zoo.

Someone rushed past him—the prostitute, fumbling in her handbag, kicking off her high-heeled shoes with a curse, running swiftly, gun drawn. It’s a man, Alexis realised: a policeman. Almost simultaneously, the drunk had moved, racing around the crags, pulling a revolver out from his brown-paper bag as he cut a quick corner to the zoo path. Alexis stood still. His brain seemed frozen, his legs paralysed. He looked helplessly at the dog-walker, but that young man was already yanking his charges towards the safety of Fifth Avenue.

Keep clear of the police, Alexis warned himself, don’t get involved. But that had been Mischa’s voice. Of that he was almost certain.

He began to follow the direction the two undercover men had taken. Again he stopped. From here he could see a man left lying on the ground, and three or four thin shadows scattering away from him as the policemen closed in. The one dressed as a woman knelt beside the inert figure—was he dead, or dying, or able to get up with some help? The other was giving chase to the nearest boy—the rest were vanishing into the darkness in all directions. Then he noticed the hat and the cane—pathetic little personal objects dropped near the body.

The policeman beside Mischa looked towards Alexis. “Hey, you there—give us a hand!”

Alexis turned, and ran.

He came on to Fifth Avenue, collected his wits while he stood listening to the hiss of wheels as the cars and taxis sped past. The traffic signal changed, and he snapped back into life. He crossed quickly, and entered Sixty-ninth Street. Kerbs were lined with cars, the sidewalks quiet, with only a few people hurrying along. Where was Oleg? He couldn’t have gone far: there hadn’t been time enough for that. Alexis’s desperation grew, he was almost into a second attack of panic. Then, just ahead of him, not far along the block, he saw broad shoulders and a dark head moving out into the street to walk round the front of a car and unlock it. He broke into a run. Oleg looked up, alert and tense: a look of total amazement spread over his face. He entered his side of the car, and opened the other door for Alexis.

“And what is this?” Oleg began angrily.

“Mischa was attacked. In the Park. Not far down the path. Police are with him—undercover police. They’ll send for more police, an ambulance. Get over there! Quick! See what’s happening, see where they will take him. Find out the hospital. Quick!”

“Why didn’t you—”

“Because they’ve seen me with him. The undercover man who was in woman’s clothes saw us both together when we met.”

“But—”

“There’s the first police car.” The siren was sounding some distance to the east, but it was drawing nearer. “Quick!” Alexis said for the third time, still more urgently. And left the car. He walked over to Madison. He did not look round.

Now it was up to Oleg. And Oleg (thought Alexis) is aware of that. He must know a good deal more than either Mischa or he pretended: being shown photographs of me, for instance, and given other particulars too—which proves he had access to my files? If he did, he’s aware that I am just an agent in place, a mole that stays underground and works out of sight. My God, I was nearly surfaced tonight. So let Oleg attend to the problem of Mischa. He would have contacts in New York. He would know how to handle this. And above all, Alexis told himself, I have my own job to do. With Mischa or without Mischa, I still have an assignment to complete. I’ll send the microfilm by the usual route, if Oleg does not contact me in Washington. This is no time to delay. If I get the information I’m after, I’m damned if I’m going to sit on it. You win no promotions that way.

He hailed a taxi to take him a short distance up Madison. From there he walked the block to Park Avenue and took a second cab. This carried him down to Fifty-third Street. There, among the tall office buildings and the Saturday-evening strollers, he walked another block to find a taxi to take him over to Second Avenue and up to Sixty-sixth Street. A circular tour, but a safety measure. He had heard of agents who had travelled for two hours on various subways, just to make sure.

It was a quarter past six when he reached the entrance of Katie’s building. He did not get off the elevator at her floor, but at the one above. For a moment he stood in the small hallway thinking—as he always did—what a stroke of genius it had been to find an apartment for Chuck Kelso right in this apartment-house.

Then he pressed the bell. He was no longer Alexis. Now he was Nealey, Heinrich Nealey—Rick to his friends—an odd mixture of a name, but genuine enough, a real live American with legitimate papers to back that up.

3

The journey from Shandon House in New Jersey to Charles Kelso’s apartment in New York took about an hour and ten minutes. It was easy—first a country road to lead through rolling meadows and apple-orchards on to the fast Jersey Turnpike lined with factories, and then under the Hudson, in a stream of speeding cars, straight into Manhattan. So Kelso had chosen to make the trip twice daily, preferring to live in the city rather than become a part of the Shandon enclave in the Jersey hill-and-tree country. Like the younger members on the Institute’s staff, he preferred a change in friends: he saw enough of his colleagues by day, he didn’t need them as social companions at night or on week-ends. As for the long-time inhabitants of the various estates that spread around Shandon’s own two thousand acres, they kept to themselves as they had been doing for the last forty years. If they ever did mention the collection of experts who had invaded their retreat, it was simply to call them “The Brains.”

So too the village of Appleton, five miles away from Shandon—it had been there for almost three hundred years and considered everyone arriving later than 1900 as foreigners, acceptable if they provided jobs and much-needed cash (cider and hand-turned table-legs had been floundering long before the present inflation started growing). On that point, the Brains were found wanting. They had their own staff of maintenance men and guards to look after Shandon House. Even the kitchen had special help. Four acres around the place had been walled off—oh, it didn’t look too bad, there were small shrubs to soften it up—but the main entrance now had high iron gates kept locked, and big dogs, and all the rest of that nonsense. And those Brains who lived outside the walls in renovated barns, or farmhouses turned into cottages, might be pleasant and polite when they visited Appleton’s general store: but they didn’t need much household help and they never gave large parties, not even for the government big shots who came visiting from Washington.

The village agreed with the landed gentry that old Simon Shandon had really lost his mind (and it must have been good at one time: a $300,000,000 fortune testified to that) when he willed his New Jersey estate, complete with enormous endowment, to house this collection of mystery men and women. Institute for Analysis and Evaluation of Strategic Studies: that’s what Simon Shandon had got for all that money. And even if the outside of the house had been preserved—a rambling mansion with over forty rooms, some of them vast—the interior had been chopped up. Rumour also said there was a computer installed in the ballroom. The villagers tried some computing themselves on the costs, shook their heads in defeat, and found it all as meaningless as the Institute’s title. Strategic Studies—what did that mean? Well, who cared? After twelve years of speculation, their curiosity gave way to acceptance. So when Charles Kelso, taking the quickest route back to the city, drove through the village on a bright Saturday afternoon when sensible folks were out hunting in the woods or riding across their meadows, no one gave his red Mustang more than a cursory glance. Those fellows up there at Shandon House came and went at all times: elastic hours and no trade unions. And here was this one, as usual forsaking good country air for smog and sirens.

But it was not the usual Saturday afternoon for Kelso. True, he had some work to catch up with; true, he sometimes did spend part of the week-end finishing an urgent job, so that the guard at the gatehouse hadn’t seen anything strange when he had checked in that morning. And he was not alone. The computer boys were on to some new assignment, and there were five other research fellows scattered around, including Farkus and Thibault from his own department. But they didn’t spend much time on one another, not even bothering to meet in the dining-hall for lunch, too busy in their own offices for anything except a sandwich at their desks. They hadn’t even coincided in the filing-room at the end of the day’s stint. It was empty when Kelso arrived to leave a folder in the cabinet where work-in-progress was filed if it was considered important enough.

Maclehose, on duty as security officer of the day, let him into the room through its heavy steel door—he always felt he was walking into a giant safe, a bank vault with cabinets instead of safe-deposit boxes around its walls. Maclehose gave him the right key for Cabinet D and stood chatting about his family—he hoped he’d get away from here by four o’clock, his son’s seventh birthday; pity he hadn’t been able to take today off the chain instead of Sunday.

“Then who’s on duty tomorrow?”

“Barney, if he gets over the grippe.” Maclehose wasn’t optimistic. “He’s running a temperature of a hundred and two, so I may have to sub for him. Thank God no one—so far—is talking about working here this Sunday.”

“I may have to come in and finish this job.”

“Pity you didn’t keep it in your drawer upstairs.” Maclehose could see his Sunday being ruined, all on account of one over-dutiful guy. That was the trouble with the young ones: they thought every doodle on their think-pads was worthy of being guarded in Fort Knox. “Then we could have locked up tight. Is that stuff so important?” He gestured to the folder in Kelso’s hand.

Kelso laughed and began to unlock Cabinet D. He was slow, hesitating. Once its door was open, he would find two vertical tiers of drawers, three to each side. Five had the names of each member of his department, all working on particular problems connected with defence. The sixth drawer, on the bottom row of the right-hand tier, was simply marked Pending. And there the NATO Memorandum had come to rest. For the past three weeks it had been dissected, computerised, studied, analysed. Now, in an ordinary folder, once more a recognisable document, it waited for the analyses to be evaluated, the total assessment made, and the last judgment rendered in the shape of a Shandon Report which would accompany it back to Washington.

“Having trouble with that lock?” Maclehose asked, about to come forward and help.

“No. Just turned the key the wrong way.”

And at that moment the telephone rang on Maclehose’s desk in the outer office.

It was almost as though the moment had been presented to him. As Maclehose vanished, Kelso swung the cabinet door wide open. He pulled out the Pending drawer, exchanged the NATO folder for his own, closed the drawer, shut the door. He was about to slip the memorandum inside his jacket when Maclehose ended the brief call and came hurrying back.

He stared at the folder in Kelso’s hand. “Taking your time? Come on, let’s hurry this up. Everyone is packing it in—just got the signal—no more visitors today.”

“How about Farkus and Thibault? They were working on some pretty important stuff.”

“They were down here half an hour ago. Come on, get this damned cabinet open and—”

Kelso locked it, handed the keys over with a grin. “You changed my mind for me.”

“Look—I wasn’t trying to—”

Sure you were, thought Kelso, but he only tucked the folder under his arm. “It isn’t really so important as all that. I’ll lock it up in my desk. Baxter will see no one gets into my office.” Baxter was the guard who would be on corridor patrol tomorrow. “Have a good birthday party—how many kids are coming?”

“Fifteen of them,” said Maclehose gloomily. The door to the filing-room clanged, was locked securely. Its key, along with the one for filing-cabinet Defence, was dropped into the desk drawer beside those for the other departments—Oceanic Development, Political Economy, Space Exploration, Population, International Law, Food, Energy (Fusion), Energy (Solar), Ecology, Social Studies.

“Quite an invasion.” Kelso watched Maclehose close the drawer, set its combination lock, and turned away before Maclehose noted his interest. “All seven-year-olds?”

“Good God,” Maclehose said suddenly, “I almost forgot!” He frowned down at a memo sheet lying among the clutter on his desk. “There would have been hell to pay.”

What’s wrong now? Kelso wondered in dismay, halting at the door. His hand tightened on the folder, his throat went dry. Some new security regulation?

Maclehose read from the memo. “Don’t forget to pick up four quarts of chocolate ice-cream on your way home.”

“See you Monday if you survive,” said Kelso cheerfully, and left.

* * *

Kelso drove through Appleton, hands tight on the wheel, face tense. His briefcase, picked up in his office, lay beside him with the NATO folder disguised inside it by this morning’s Times. He had opened the briefcase for the obligatory halt at Shandon’s gates, but the guard had contented himself with his usual cursory glance through the car’s opened window. After four years of being checked in and out, inspection of Kelso had become routine. Routine made everything simple.

All too damned simple, Kelso thought now, turning the anger he felt for himself against Shandon’s security. I should never have got away with it. But I did.

He had no sense of triumph. He was still incredulous. The moment had been presented to him, and he had taken it. From then on there had been no turning back. How could he have done it? he wondered again, anger turning to disgust. All those lies in word and action, the kind of behaviour he had always condemned. And yet it had all come so naturally to him. That was what really scared him.

No turning back? He slowed up, drew the car to the side of the narrow road, sat there staring at his briefcase. Now was the time, if ever. He could say he had forgotten something in his office: he could slip downstairs to the filing-room—Maclehose would have left by now. He had the combination of the key drawer—127 forward, back 35—and the rest would be simple. Simple: that damned word again.

And yet, he thought, I had to do it. There was an obligation, a need. I’ve felt it for the last three weeks, ever since I worked over the first section of the Memorandum along with Farkus and Thibault. Yes, we all agreed that the first section should have been published for everyone to read. Now. Not in ten, twenty, even fifty years, lost in the Highly Classified files until some bureaucrat got round to releasing it.

The other two sections—or parts—of the NATO Memorandum were in a different category. From what he had heard they were top secret. Definitely unpublishable. Unhappily, he glanced again at the briefcase. He wished to God they were back again in the Pending drawer. But he had had only a few moments, less than a full minute, not time enough to separate them from Part I of the Memorandum and leave them in safety. All or nothing: that had been the choice. So he had taken the complete Memorandum. The public had the need to know—wasn’t that the current phrase, highly acceptable after the secrecies of Watergate? Yes, he agreed. There was a need to know, there was a moral obligation to publish and jolt the American people into the realities of today.

He drove on, still fretting about means and ends. His conduct had been wrong, his purpose right. If he weren’t so sure about that...but he was. After three miserable weeks of debating and arguing with himself, he was sure about that. He was sure.

* * *

He was late. First, there was a delay on the New Jersey Turnpike, dusk turning to night as he waited in a line of cars. A truck had jack-knifed earlier that afternoon, spilling its oranges across the road, and it was slow going, bumper to bumper, over the mess of marmalade. Next, there was a bottle-neck in Saturday traffic on the Upper East Side of Manhattan—huge caterpillars, two cranes, bulldozers, debris trucks, even a powerhouse, were all left edging a new giant excavation until Monday morning. If there was a depression just around the turn, these hard-hats didn’t know it. And then, last nuisance of all, with night already here, he found all the parking spaces on his own street tightly occupied. He had to leave his car three blocks away and walk to Sixty-sixth Street, gripping his briefcase as though it contained the treasure of Sierra Madre. Yes, he was late. Rick had probably called him at five exactly; Rick seemed to have a clock planted like a pacemaker in his chest. It was now ten minutes of six.

“One hell of a day,” he said aloud to his empty apartment. Switching on some lights, he placed the briefcase on his desk near the window and looked for any messages that Mattie, his part-time help, might have taken for him this morning. There was one. From his brother’s wife, Dorothea. He stared at it aghast. Mattie had written out the message carefully, although the hotel’s name had baffled her. “Staying this week-end at the Algonekin. Can you make dinner tonight at seven thiry?” God, he thought angrily, of all the nights for Tom and Thea to be in town! And then he began to remember: Tom was on his way to Paris on one of his assignments, and Thea was here for a day or two in New York. But surely they hadn’t told him it was this week-end? Or had he forgotten all about it? His sense of guilt deepened.

He left the desk, with the typewriter-table angled to one side of it, navigated around a sectional couch and two armless chairs in the central area of the room, skirted a dining section, reached the small pantry where he stored his liquor, and poured himself a generous Scotch. Of all the nights for Tom to be here, he kept thinking. He dropped into a chair, propped feet on an ottoman, began trying several excuses for size. None seemed to fit. Best call Tom and say that he just couldn’t make it. Not this time, old buddy. Sorry, really sorry. See you on your way back to Washington. No, no...that was too damned cold.

He sighed and finished his drink, but he didn’t move over to the telephone. He went into the bathroom and washed up. He went into the bedroom and got rid of his jacket and tie. He put on some discs on his record-player. And when he did at last go to the desk, it was to open the briefcase. Plenty of time to get in touch with Tom—it was barely six-fifteen. Yes, plenty of time to find some explanation that would skirt the truth (“Sorry, Tom. I forgot all about it.”) and yet not raise one of Dorothea’s beautiful eyebrows.

The doorbell rang. Rick?

4

It was Rick. “Sorry I couldn’t ’phone. Spent the last hour getting here from La Guardia. Traffic was all fouled up. He was at ease as he always was, a handsome man of thirty-three, blond and grey-eyed (he had that colouring from his German mother); but at this moment his face looked drawn.

It’s the harsh light in this hall: I’ll have to change the bulb, thought Kelso. He caught sight of himself in the mirror, and he looked worse than Rick—everything intensified. His dark hair and brown eyes were too black, his skin too pale, the cheekbones and nose and chin had become prominent, his face haggard. “What we both need is a drink,” he said, dropped Rick’s coat on a chair and led the way into the room.

“Nothing, thanks.” Rick’s glance roved around, settling briefly on the desk and the open briefcase. He restrained himself in time, didn’t make one move towards it. Instead, he watched Chuck pour himself a drink. “You look wrung-out. A bad day?”

“Hard on the nerves.”

“What happened?”