6,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

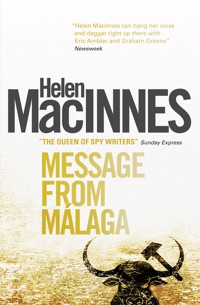

Under the Mediterranean sun, a drama begins in a cafe courtyard in M álaga. For Ian Ferrier, an employee of the United States Space Agency on a vacation visit to his old friend Jeff Reid, it means the startling discovery that Reid is not just a wine exporter, but also a CIA operative, charged with smuggling communist defectors to the West. Events take a disastrous turn for the worse when Ferrier, a stranger both to Spain and to the deadly world of espionage, is forced to take sole charge of a high-ranking KGB agent. Alone in an beguiling but alien country, he can afford no mistakes when choosing between friend and foe...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

ALSO BY HELEN MacINNES

AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Pray for a Brave Heart

Above Suspicion

Assignment in Brittany

North From Rome

Decision at Delphi

The Venetian Affair

The Salzburg Connection

While We Still Live

The Double Image

Neither Five Nor Three

Horizon

Snare of the Hunter

Agent in Place

Message From Málaga

Print edition ISBN: 9781781163337

E-book edition ISBN: 9781781164365

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: December 2012

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

© 1971, 2012 by the Estate of Helen MacInnes. All rights reserved.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book?

We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at:

[email protected] or write to us at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website.

www.titanbooks.com

For my friend Julian

a man who has never given up the ship

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

About the Author

1

So this, thought Ferrier, was El Fenicio, an open courtyard behind a wineshop, a rectangle of hard-packed earth on which rows of small wooden tables and chairs had been set out to face a bare platform of a stage. Its four walls were the sides and backs of two-storied houses, old, faceless except for a few windows, tightly shuttered, and a single balcony, dark, withdrawn. Lights were sparse and haphazard, a few bare bulbs attached high on the walls, as coldly white as the moon overhead, but softened by the clusters of leaves and flowers that cascaded from the vines and ramblers climbing over the worn plaster. There was the lingering scent of roses still heavy with the heat of day. There was the smell of jasmine as ripe as sun-warmed peaches, fluctuating, tantalising. And there was the music of a solitary guitar, music that poured over the listeners at the tables, surged up the faded walls, escaped into the silence of night and a brilliance of stars. It seemed, Ferrier imagined, as if the perfume of the flowers suited its mood to the ebb and flow of sound, weakening or strengthening when the guitar’s chords diminished or soared. His touch of fancy amused him: he had come a long way from the tensions and overwork of Houston, a longer way than the thousands of miles that lay between Texas and Andalusia. He hadn’t felt so happily unthinking; so blissfully irresponsible in months. He lifted his glass of Spanish brandy in Jeff Reid’s direction to give his host a silent thanks—not for the brandy, it was too sweet for Ferrier’s taste, but for this beginning to what promised to be a perfect night.

It was all the more perfect because he hadn’t quite expected anything like El Fenicio. “Some flamenco now?” Reid had asked at the end of a late and long dinner. “The real stuff. None of those twice-nightly performances for the tourist trade along the Torremolinos strip. I know a little place down by the harbour. Friday is good there. It will be packed by one o’clock. We’d better drop in around twelve-thirty and make sure of my favourite table. You like flamenco, don’t you?” Ferrier nodded, pleased by the fact that Jeff had remembered his taste in music, but a bit doubtful, too. He was thinking of the little places down by the harbour that he had seen in Barcelona, in Palma. What difference would there be in another seaport town, like Málaga? The little place meant a small dark box, a hundred degrees in temperature and unventilated, with an ageing tenor in a bulging black jacket, puffy white hands clasped before him in supplication to an unseen mistress, his thick neck straining to bring out the high notes of the Moorish-sounding scales but only producing a sad cracked wail. The little place meant anervous guitarist disguising mistakes in a flourish of sound. It meant one dancer, elderly, thickset, trying to compensate for lost technique by the height she twitched her flounced skirt up over a naked thigh. It meant three or four fat women dressed in screaming pink or virulent green, the shiny satin of their tight dresses as artificial as their purple smiles, as furrowed as their tired faces, as hard as the jagged mascara around hopeless eyes, who sat together at a table near the staircase (there was always a narrow staircase climbing up one wall of the room) and measured the rough mixture of foreign seamen and nervous tourists who imagined they were seeing a bit of authentic Spain. The little place was too often a sad place, of failures and might-have-beens, of vanished hope and flourishing despair. But Ferrier had kept his doubts, to himself and thank God for that, although he had made a feeble try to sidetrack Jeff: “There’s no need to make an effort to entertain me. I’m perfectly happy—” Reid had cut in with his warm smile, “Well—just to please me—will you come? I haven’t yet missed a Friday night at El Fenicio.” So Ferrier retreated with a joke. “What?” he asked. “No wonder you never find time to get back to the States for a visit. Is this part of your job?” Reid looked at him sharply, then laughed. “Oh, a business-man has to have some compensations.”

And now, as Ian Ferrier listened to the guitar—no microphones here, no electronic jangle—and wondered what the music was (perhaps an original composition based on a malagueña?) and then decided it didn’t matter—all that mattered was the sound that caught one’s heartbeat, sent one’s pulse quickening—he had a strange attack of conscience. He glanced at Reid, lost in his own thoughts like all the silent listeners in the crowded courtyard, and realised that if anyone had changed in these last eight years, since Reid and he had met, it was not Jeff; it was he who had altered most. At thirty-seven, you’re become a self-centred bastard, he told himself: you want everything your own way, don’t you? And if he blamed this moment of truth on the combination of guitar, scent of flowers, night sky glittering above him, he had only to remember the way he had almost ruined the journey to Málaga with his reservations and doubts and afterthoughts. Those damned afterthoughts... At one point, he had almost cancelled this whole trip.

* * *

That afternoon, he had driven across the mountains, leaving fabulous Granada behind him, and headed dutifully for the Mediterranean. (Dutifully? That was the word. He wasn’t bound for a lazy beach and blue water, or a picturesque fishing village.) His emotions had been not only mixed but also definitely roiled. He was having an attack of second thoughts, and they were always an irritation, especially when it was too late to do anything about them. He had only himself to blame, of course: this was what he got for imagining he could snatch a visit to Granada in between a week of professional business (and how did that creep into his vacation time, anyway?) and a couple of days with an old friend. It had seemed a good idea, back in Houston, to write Jeff Reid that he was coming to Europe, that part of his time would be spent in Spain, that naturally of course most definitely he’d make a point of dropping in on Málaga—if that suited Jeff. It did. Jeff had replied that eight years had been far too long since their last meeting; and the exact date was set. Perhaps that was what depressed him now: he had quite enough of exact dates and deadlines in his present job with the Space Agency. Or perhaps it was just that a glimpse of Granada was too damned unsettling. He kept feeling—well, not exactly cheated. Frustrated? It was like being passionately kissed by a beautiful woman who slipped out of your arms and vanished.

He had routed that attack of gloom by concentrating on some high-speed driving over a winding, narrow, but well made road that cut along the top of hillsides. (Okay, okay, forget that Málaga was listed in the guide-book as a bustling, modernised town; just remember you wanted to see Jeff Reid again.) The Spaniards, wise birds, were having their long siesta in this intense heat of day; the road was empty for twenty miles at a stretch, the village streets were as deserted as if plague had struck them, the vast stretches of fields and olive groves that sloped into great valleys lay abandoned to the sun. He had Spain to himself. And as a backdrop, there were the jagged Sierra Nevada peaks, crowned with snow even in June, sawing into one of Spain’s best blue skies. Then he came down from the hills and the pine trees to an abrupt edge of coastline, where terraced vineyards ended in cliffs that dropped steeply into sea. He liked that. He liked the sugar-cane fields, too, and a couple of ruined Moorish castles and the fishing villages. Until he began to see some high-rise hotels and French restaurants. Progress, progress... His depression returned full whack as he drove into Málaga and found himself—siesta time now being over—in the same thick syrupy congestions of city traffic that he could enjoy anywhere in America. Was this what he was travelling abroad for?

Reid had sent him a rough sketch of the district where he lived. “You’ll find me easily,” he had written. “An old Air Intelligence type like you doesn’t need instructions how to get anywhere.” So the directions, if concise and clear, were minimal. The crisscross of smaller streets, no doubt an unnecessary complication to an old Air Reconnaissance type like Jefferson Reid, was left unmarked. At last, almost an hour later than he had hoped, Ferrier found the place. He stared at the large house, retreating behind palm trees and flowering shrubs, a replica of its neighbours in their equally lush gardens along this placid street. A villa, no less. And there must be servants to go with it. Good God, had Jeff Reid changed as much as all this? Was he really a settled business-man, with a position to keep up, living abroad, avoiding some taxes and all the headaches of present-day America? It certainly looked as if the sherry business was thriving—Reid was head of the Spanish branch of an American wine-importing firm. Well, thought Ferrier, as long as Jeff hasn’t changed into a complacent fat cat, all the more power to him. But he found he was climbing slowly out of his rented car, taking his time in picking up his jacket and bag. He felt his sodden summer shirt clinging to his back muscles, his trousers sticking to his buttocks. The truth was—and at the last minute he was admitting it fully—the truth was that old friendships could atrophy. That had been the core of his depression all the way here. People changed. And all the irritations and annoyances that had almost ruined the journey for him were simply excuses to cover his real doubts.

But there had been no need to worry. Reid’s welcome was no pretence, no sentimentalised fake. The changes were superficial. His dark hair had grown thinner on top and grey at the temples. He had put on ten pounds (his height carried them well, even needed them), and developed a permanent tan. He had adopted the snow-white shirt and narrow black tie of a Spanish business-man along with his precise tailoring, and looked so smooth that Ferrier might easily have passed him by if he had been sitting at a café table over a small cup of ink-black coffee. But the handshake was strong, the eyes sympathetic as they studied Ferrier’s tired face, the voice both casual and warm. “You look like a man who needs a long cool drink, a cold shower, and part of the siesta you wouldn’t take. In that order. When did you get to bed last night? By the dawn’s early light? Actually, I laid a bet with myself that I’d never pry you loose from Granada. Glad I lost, though. What about dinner at ten? See you down here then. Okay?” Very much okay, Ferrier thought, accepting the tall drink with the admirably clinking ice that Reid held out to him, and followed the middle-aged woman who had already carried his bag halfway upstairs. This was Jeff Reid, all right. They might have seen each other only last week, and not eight years ago. Yes, it had been worth the trip to Málaga, if only to find that old friendships could take up where they had left off.

* * *

In the courtyard, the music quickened. The guitarist brought the last surge of rippling notes into a falling diminuendo of one, listening to its last sigh as intently as the people sitting before him. The note faded slowly into nothing. There was a long moment of silence, all eyes watching the stage—a giant table, almost twelve-foot square and a hand span thick, with four massive barrel legs—that was backed against the end wall of the courtyard. The applause broke out, crisp, brief, critically measured. It pleased the guitarist enough, though. He inclined his head gravely, his gaunt face relaxed a little, intense dark eyes lingering only briefly on his audience as if they scarcely existed. He was good, and they knew it, and that was sufficient. He lifted his narrow-backed chair in one hand, swung it lightly into place at the end of a row of six others before the bare plaster wall.

“No encore?” Ferrier asked. “Or didn’t we clap loudly enough?”

“He has plenty to do later on.” Reid glanced at his watch, then back at the stage, where the guitarist had sat down again and was concentrating on some silent fingering. Reid looked at the open doorway near them, a narrow space without any light tacked overhead, shadowed still more by a cascade of bougainvillaea. There was no sound of women’s voices, no movement from inside the door, no one gathering there to join the guitarist on the stage.

“One o’clock,” Ferrier verified from his watch. “Isn’t that when the show really gets moving?”

Reid said lightly, “Oh, you don’t keep account of time in Spain. Ten minutes here, half an hour there, what does it matter if you are with friends?” And delays happened: dancers’ dressing-rooms had more than their share of tantrums and temperament. But, Reid wondered, was this the beginning of a natural wait? Or was it being carefully engineered by Tavita to last precisely fourteen minutes? If so, then it was no ordinary delay, but a warning signal from Tavita—one that only Reid in all that crowded courtyard could understand and act upon. (It had been Tavita’s idea of how to preserve security—one that had amused him at first, even embarrassed him, but he had let her have her way. She had confidence in it. And it had been successful. No one had ever noticed. What more did he want?) Well, he thought as he controlled his rising tension, if this is the beginning of an alert, I’ll know in exactly fourteen minutes. And what do I do then, with Ian Ferrier sitting beside me? Just as I usually do, I suppose: wait until the dancing starts and all eyes are riveted on the stage and I can slip away. And Ian? My God, it would have to be tonight that an emergency happened... All right, all right let’s wait and see if this turns out to be a signal. Just wait and see. Meanwhile, talk. “We’re in luck,” he told Ferrier. “Usually there are six chairs on that stage. Tonight, seven. So Tavita is dancing. For my money, she is one of the best in Spain, but it is only at the weekend that we can get her down from Granada. That’s where she lives.”

“Oh?” Ferrier was definitely interested.

“Not in a cave with the gypsies,” Reid added. “She has a house on top of a hillside, not far from the Alhambra. An artist left it to her when he died—his paintings of her are all over the place. Yes, she’s quite a girl.”

“Nice going; lives in Granada, dances here. But why not in Granada?”

“Since the tourists get taken by the hundreds in the gypsy section of town? No, not for Tavita. She’s a purist. Flamenco is something she really believes in. She dances in Seville, mostly. On Fridays, she dances here.”

“But why?” In Málaga? And was I just another gullible tourist in Granada? Ferrier wondered. He supposed that idea was good for controlling his ego, but he didn’t enjoy it.

“Out of sentiment. Also—” a smile spread over Reid’s face—she owns El Fenicio.”

“Nice going. I placed him as the owner.” Ferrier nodded discreetly in the direction of the middle-aged man with a thin and furrowed face, thick black hair, large dark eyes, who stood near the main entrance. He had greeted Reid with a handshake and Ferrier with a restrained bow.

“Esteban? He manages El Fenicio for Tavita—he’s one of her old bullfighter friends. Tavita got her start as a dancer here when she was fourteen. It was a wineshop with a staircase down to a small cellar in those days. She never forgets it, though.”

“And they don’t forget her?” Ferrier looked around him. There were only a few women, quietly dressed, obviously married, well guarded by a phalanx of males. And the men? A mixed crowd, in age and appearance, but whether their clothes were cheap or expensive their appearance was well brushed and washed, either as a compliment to El Fenicio or as a matter of self-respect. The contrast between them and a group of four young men who had just arrived in bedraggled shirts and stained trousers was so marked that the newcomers might just as well have entered shrieking.

“All dressed for a hard day’s work in the fields,” Reid said, and looked away from the group. They were being led to the last free table in a back corner, and didn’t think much of it. Their protest didn’t have much effect on Esteban: take it or leave it, his impassive stare said; preferably leave it. “They’d have to be American,” Reid added with a touch of bitterness, as he listened to their voices. “Just hope those two tables of dockworkers down front don’t decide to move back and have some fun. They’re allergic to people who make a mockery out of poverty. That’s how they see the fancy dress. If these kids were poor and starving, they’d give them sympathy, even help. But the poor don’t travel abroad; the poor can’t afford cafés and night clubs; the poor don’t have cheques from home in their pockets.”

“Kids?” Ferrier asked with a grin. The one with the beard might be in his teens, but two others—one white, one black—were certainly in their twenties; and the fourth, who wore his dark glasses even in moonlight, might be closer to thirty. “You know, I think I’ve seen one of them before.” Thin beard, young unhappy face, drooped shoulders and all. But where? Today... Not in Granada. Here in Málaga, when I was driving around searching for numbers on a street: Reid’s street, in fact. Almost at Reid’s gate, that’s where I saw him. “No importance,” he said. “He was just like me—another lost American.” But he’s still lost, Ferrier thought, lost in all directions. Then, his attention was switched away from the back-corner table to the doorway beside him. Another guitarist had emerged to make his way slowly to the stage. He was followed by a white-faced man, middle-aged, plump, whose frilled shirt was cut low at the collar to free the heavy columns of his neck. The singer, of course. A young man came next, one of the dancers, tall and thin, with elegantly tight trousers over high-heeled boots and a jacket cut short. He disdained the three rough steps that led up to the stage, but mounted it in one light leap without even a footfall sounding. Control and grace, admitted Ferrier, but how the hell does he manage to look like a real man even with a twenty-inch waist? Strange ways we have of making a living. My own included. Who among all these Spaniards would guess what I do? And here I am, the most computerised man among them, yet less formal than most of them in dress and certainly less controlled. No one else was showing any impatience. The two guitarists had started a low duet, a private test of improvisation between them; the dancer, standing behind them along with the singer, was tapping one heel at full speed, quietly, neatly, as if limbering up; the singers looked at nothing, at no one, perhaps concentrating on a new variation in tonight’s cante jondo; the tables continued their quiet buzz of talk, a few men rose to talk with friends or make their way to the lavatory, and all Reid had done was to glance casually at his watch. Ferrier concentrated on the Spaniards around him. “Who are they? Longshoremen and who else?”

Eight minutes to go—if this was an alert. Reid’s attention swung away from the questions in his mind and came back to the courtyard. “Well, of the regulars here, I can pick out fishermen, a lawyer, a couple of bullfighters, some business-men, an organist, several artists, workers from the factories across the river, shopkeepers, and students. And a policeman.” He dropped his voice judiciously. “That’s him, the man in the light-grey suit at the table just in front of our four fellow citizens.”

“State Security?”

Reid nodded.

Ferrier, sitting sideways at the table, could glance briefly, toward the back corner of the courtyard without swerving his head around. He saw a man in his mid-thirties, small, compact, cheerful, with dark complexion and curling hair. He seemed to be concentrating on his companions, who were talking volubly. “Who are the two men with him?”

“A journalist, and a captain of a freighter that docked this morning. From Cuba.”

“And where’s that?” They exchanged smiles, remembering the missile crisis, a tricky situation indeed, that had brought them together in a strange way. Reid had been one of the flyers who had volunteered to take photographs, at a low and dangerous level, of Khrushchev’s rocket installations in Cuba. Ferrier had been one of the intelligence group who had analysed the original photographs taken at high altitude, discovered the area that seemed to deserve closer attention, called for some low-altitude shots, and found the sure proof. “We ought to work together more often,” Ferrier said.

“We certainly called Papa Khrushchev’s bluff that time.”

“Do you do any flying nowadays?” Ferrier’s question was purposefully casual. He wondered for a moment if he’d ask Jeff outright why he had resigned from the Air Force. Sure, he had had a bad smash up, still flying too low, still taking dangerous chances for a more closely detailed photograph. At the time, he had said he didn’t want to be pushed into a desk job, and with his injuries that was certainly where he was heading; but what was a business-man except someone attached to a desk? That separation from his wife had something to do with it. He had moved abroad soon after, which was one way of definitely putting distance between himself and Washington where Janet Reid lived. But I can’t ask him about that, either. Not directly. Several of Jeff’s friends had lost him completely, trying to nose into that puzzle. And now Jeff wasn’t even answering his question except with a shake of his head. So Ferrier backed off tactfully, tried another angle. “Interesting town, Málaga. I begin to see how you enjoy it. Plenty of action, movement in and out.”

Reid looked at him sharply, then relaxed. “Oh, we get a bit of everything wandering through here, from honest tourists to strayed beatniks and travelling salesmen.”

“Not to mention all those freighters along your docks, packed like cigars in a box. Stowaways and narcotics and smuggling in general?”

“All the headaches of civilisation. But at least there has been peace and growing prosperity. I’ll take that, headaches and all, over war any day.”

“And civil war, at that,” Ferrier said quietly. He was looking at the packed courtyard, a mass of faces waiting expectantly as they talked and laughed and listened to the guitars’ improvisation. Incredible, he was thinking, how people can look so damned normal as they do, when they’ve been through so much. Sure, it was thirty-odd years ago, another generation, and yet... He shook his head and added, “I keep remembering what you told me about it, on our way here—”

“If you must talk about that, keep your voice down.”

“It’s down. We are both mumbling like a couple of conspirators.”

“And that,” Reid said, trying to look amused, “is not too good either.”

What’s wrong? Ferrier wondered. Jeff is suddenly on edge. And that’s the third time he has glanced at his watch. What’s worrying him? Does he think that Tavita may decide not to dance, after all, and the whole evening becomes a letdown? Not just for me. These quiet faces around me—how would they react? “Okay,” he said. “Voices back to normal. No more questions about their civil war. I asked you enough of them, anyway.”

“It wouldn’t be the old Ian if you didn’t,” Reid said, but he made sure of changing the subject by starting some talk on the history of this courtyard. Its name, El Fenicio, was a reminder of the Phoenicians who had founded Málaga, long before the Romans had even got here.

Ferrier listened, but his own thoughts were wandering. His mind kept coming back to Jeff’s answers to his questions this evening as they had driven down through the city towards the wineshop.

* * *

Ferrier had looked at the busy streets through which they were travelling slowly, at the bright lights, the crowded cafés, the masses of people on the sidewalks. “They’ve forgotten,” he had said. “Or didn’t the Civil War touch them much?”

Reid had stared at him. “They haven’t forgotten. That would be difficult,” he had added grimly.

“Was it as bad as that here? In Málaga?”

Reid had nodded. “That’s why they don’t talk much about it. Not to me, not to—”

“But you’ve lived here for almost eight years.”

“I’m still el norteamericano when it comes to politics; let’s not kid ourselves about that. There’s such a thing as an experience gap, you know. We didn’t go through what they suffered.”

“Some foreigners did.”

“Only for a couple of years. They weren’t here before the war started, or after it ended. They didn’t live through twenty years of misery.”

“Twenty?” Ferrier had been disbelieving.

“I’m not even including the years when grudges and hate were built up, long before the violence really started.”

“And when did it?”

“In Málaga? 1931. Forty-three churches and convents burned in two days. A pretty definite start, don’t you think?” Ferrier had been puzzled. (As someone who had been brought up on Hemingway and graduated to Orwell, he thought he knew something about Spain.) “Have you got your dates right?” he asked half-jokingly. “There was an elected government in power then. Newly elected, too. It didn’t have to burn and terrorise. It had the votes.”

“And couldn’t control its anarchists. Not in Málaga, certainly. Those burnings took place just one month after the Republic was declared.”

“But that doesn’t make sense!” Anarchists and communists had been on the side of the Republic. “Unless, of course,” Ferrier said thoughtfully, “it was some kind of power grab.”

“It was just that. The Republic was never given a fair chance. The anarchists had their ideas of how to dominate the scene; the communists had their own plans for coming out on top—anything that created a revolutionary situation was all right with them. So things went wild. Burning, looting, kidnapping, killing. Málaga had five years of that before the Civil War really got going. And you think no one remembers? Look—they have only to walk down their most important street—the one we have just passed through, all modern buildings and plate-glass windows. When you looked at it, what did you think all that newness meant?”

“I didn’t think. I just assumed. Natural growth of an active city.” Experience gap, thought Ferrier. He was being given a sharp lesson in the meaning of that phrase. But he had asked for it.

“Once, it had historical buildings, some fine architecture; a kind of show place. It also had rich families and art objects—an unhappy combination when anarchists are taking revenge. In 1936, it became a stretch of burned-out rubble.” Reid’s tone was quiet, dispassionate. In the same even way, he continued, “A couple of months later, the Civil War started. You know what that meant. Bravery on both sides; and cruelty, and hate, and vengeance. At one point, the communists thought they were going to win, and that’s when they made sure the anarchists wouldn’t give them any future trouble. So it was ‘Up against the wall, comrade anarchist!’ Literally. In Barcelona—but you know about that?”

“I’ve read my Orwell. The anarchists were shot by the hundreds, even thousands, weren’t they?”

“Just after they had come out of the front-line trenches. Their rest period.” Reid shook his head. “I don’t know why that seems so particularly bloody in all that bloody mess. The right wing would call it poetic justice, I suppose. But I’ve never seen anything poetic in justice: it’s too close to reality. And the realities went on, and on, long after that war was over. Starvation and poverty—the outside world never heard the half of it. But what else do you expect from so much destruction? The food source was gone: cattle, fields, ranches, farms. And jails and executions for men who had jailed and executed others.” Again he shook his head. “The innocent suffered too—on both sides. They always do. Whether you won or lost in that war, there was plenty of misery for everyone.”

Civil war... “A lesson for all of us,” Ferrier said. “Don’t take anarchists or communists as your political bedfellows unless you want to wake up castrated.” The twentieth-century experience, he thought. “But the radicals never learn, do they?”

“Nor do some nationalists,” Reid said bitterly. “If trouble breaks out here again—” He didn’t finish that thought. “The hell with all extremists,” he said shortly. “Their price is too high.”

* * *

Ferrier’s thoughts came back to the courtyard. Around him, the tables were buzzing with talk; expectations were rising—you could hear it in the gradually increasing volume of sound. Everyone was out to enjoy himself. Ferrier looked at Reid. “Sorry. My mind drifted. You were saying the Phoenicians—?”

“Not important. Just a footnote.” Only a brief remark to keep Ian from noticing this delay too much. It was ten minutes past one now. Four minutes to go. If this was an alert. “You know, Ian, you’re a lucky man. You have a job that’s worth doing, a job you like. You can keep your eyes fixed on the stars and not worry about politics.” Because that’s all I do now, Reid thought. I, too, have a job that’s worth doing, but before I entered it I hadn’t one idea of how much worry was needed over politics. The things that never get known, that can’t be published unless you want to throw people into a panic; the things that stand in the shadows, waiting, threatening; the things that have to be faced by some of us, be neutralised or eliminated, to let others go on concentrating on their own lives.

“Not worry?” That had caught Ferrier’s attention. “I wish I could keep my eyes on the stars instead of all that junk that’s floating through space.”

Reid studied his friend thoughtfully. “It’s more than junk that’s bothering you, isn’t it?”

Ferrier nodded. “What about a nice big space station up there? Not ours. What if a politically oriented country got it there first? One that doesn’t hesitate using an advantage to back up its demands?”

“Another blackmail attempt, as in Cuba?”

“1962 all over again. Except, this time, the rocket installations would be complete with armed missiles or whatever improvements the scientists can dream up,” Ferrier said bitterly. “And the whole, damned package would be right above our heads, way out there.” He looked up at the sky. “Not to mention various satellites that now have their orbits changed quite easily to remote control. God only knows what they contain.” He tried to lighten his voice. “Well—one thing is certain. There is no future in being ignorant. Or in being depressed. You know what’s at stake and you keep your cool. If you don’t, you’ve had it.” He finished his drink, didn’t taste it any more.

Reid looked around for the waiter. “Where’s Jaime? Oh, there he is—transfixed by our fellow-Americans.” He clapped his hands to signal to the boy, small and thin, who had been standing against the rear wall.

Ferrier glanced briefly in Jaime’s direction, caught a passing glimpse of the back-corner table. Four pairs of eyes had been levelled at him—or at Reid. Four pairs of eyes automatically veered away as he noticed them. It was a very brief encounter, and if there hadn’t been that unified evasive action, Ferrier would have thought his imagination was playing tricks. “Ever seen these fellows before?”

“I’ve seen a thousand like them in the last three years.” Reid was concentrating on Jaime, who was just arriving with expert speed. “Like to try the wine this time? It’s local, out of a barrel, sweet but nourishing. There isn’t much choice, actually. This is grape territory.”

“I’ll stick with the brandy. Sweet but less nourishing.” And after Reid had given the brief order and Jaime, with a bright smile on his lips and in his eyes, had left them, Ferrier said, “I admire your Spanish. But doesn’t he know English? He seemed to be listening to what I was saying.”

“He’s learning. And if I know Jaime, he’s fascinated by your jacket. He’s going to save up and get one just like it.”

“One thing about Jaime—he could teach those fellows back at the corner table how to look cheerful.”

“You should see the village he comes from, back in the hills. It was one of those that almost starved—”

From the doorway came the sound of women’s voices, a burst of argument still going on, a quick command, silence. And then a rattle of castanets, light laughter. A clatter of heels came over the wooden threshold as four girls stepped into the open. There was a rustle of silk as wide ruffled skirts swept toward the stage in a mass of floating colour. Smoothly brushed heads, each crowned by one large flower, were held high, long heavy hair caught into a thick knot at the nape of slender white necks. Three profiles were turned just enough to let the courtyard see a long curl pressed closely against a barely pink cheek, dark-red lips softly curving, an elaborate earring dangling. The fourth girl, lagging behind although she walked with equal poise and dignity, paid no attention to anyone, not even to the quick flurry of guitars reminding her, with a sardonic imitation of a grand fanfare, that she was later than late. The male dancer greeted her with a burst of hoarse Spanish that set the others laughing. She tossed her head, drew the small triangle of fringed silk that covered her shoulders more closely around her neck, sat down with her spine straight and a damn-you-all look at the front tables. The longshoremen roared.

“Constanza,” Reid was whispering. “She’s always in trouble. But her temper improves her dancing.” He looked at his watch. Almost fourteen minutes. Tavita’s exact timing never failed to amaze him.

To Ferrier’s ear, there seemed to be some slight trouble at the rear of the courtyard, too: an American voice briefly raised in anger, a sharp hiss from the neighbouring Spaniards that silenced it. He glanced back with annoyance, saw the youngest of the four—the bearded one—heading towards the wineshop, thought that this was a hell of a time to choose to go to the men’s room, looked once more at the stage. The girls, a close cluster of bright colours, were settled in their seats, leaving the last chair free. The singer and the male dancer stood behind the guitarists at the other end of the row. The lamps around the courtyard walls went out. A softer glow, as amber as candlelight, focused on the stage. Suddenly he was aware that another woman had entered from the door beside their table. Silence fell on the courtyard.

Good God, thought Ferrier as he glimpsed her profile. She brushed past them, paying attention to no one. Reid was no longer looking at his watch. The silence intensified.

She was taller than the others, Ferrier noted, and moved with a grace that was notable even by the dim light. She reached the stage, mounted it, walked its length toward the empty chair with that same effortless stride. Around him, the silence broke into a storm of welcome. He could almost feel the excitement that filled the courtyard before it swept over him, too. She was worth waiting for, this Tavita. A small delay, it seemed now, not worth noticing; a little time lag that had served to stir the emotions and rouse expectations. She was unique, no doubt about that, although she was dressed like the others in the stylised costume of flamenco. And it wasn’t her selection of colours that was so different—the others had made their choices, too, combining favourite contrasts to give variety. It was the way she wore the splendid clothes. She dominated them, made them part of her individuality.

She had reached her chair, sat down with her spine erect and head high, like all of them and yet like none of them, sweeping aside her wide skirt with a slender arm so that its rippling hem spread out on the wooden floor like an opened fan around her feet. The sleeveless top of her dress was black and unadorned. It moulded her body, from low rounded neckline down over firm breasts and taut waist almost to the line of her hips. There, the many-tiered skirt, black lace over red silk, belled out in a cascade of ruffles that ended above her ankles, dipping slightly in back almost to the heavy high heels of her leather pumps. These were the practical note, the classical shoes of the flamenco dancer, which could beat out lightning rhythms like a riffle on a drum. The small red shawl, fringed in black, was practical too: it covered the bare back and shoulders against the cool touch of early-morning air. But the flower in her elaborately simple hair was completely exotic, large, softly frilling, startlingly pink. She wore long earrings to balance the curl over her cheek, but no necklace, no rings, no bracelets. The bones of her face were strong yet finely moulded, cleverly emphasised by the skill of her make-up. Her large dark eyes were shining, her smile lingering. “Good God,” Ferrier said again, aloud this time.

Suddenly, without any apparent signal, any noticeable exchange of glances, the four girls rose and swept into a round with the first bright chords of the sevillana, paired off, laced, separated, came together again, filling the little stage with a swirl of skirts, a flurry of heels struck hard, a crack of castanets from upraised hands. The guitars quickened, heightened, their rhythms marked by hard hand-clapping from the singer and dancer. From Tavita, too. Her eyes were watching the stamping feet with pleasure and excitement, her smile breaking into laughter. “Go! Go!” she called out to Constanza. “Anda! Anda!”

Reid was studying Ferrier’s face. “This is just for openers, you know. The individual dancing comes later.”

“They really enjoy themselves.” And I along with them. “Why the hell don’t I give up my job, move here, see this every night?” Ferrier settled back in his chair. At this moment, he thought, I am a very very happy man.

Reid said softly, as Jaime came out of the darkness and placed their brandy before them, “Excuse me for a few minutes, will you? This is just as good a time as any—Pablo will have to dance, Miguel to sing, Constanza or Maruja to demonstrate an alegria, before we get Tavita’s performance. Don’t worry, I won’t miss that. Hold the table. Some of the late comers are ready to pounce on any free space.”

Ferrier nodded, his eyes on the stage. But he was aware that Reid had moved, not toward the back of the courtyard, where others had previously sauntered out to the washroom, but through the door in the wall beside him. Special privilege, Ferrier thought, and was briefly entertained. And then he forgot about Reid as the climactic moments of the sevillana, with violent strumming and rapping on the guitars, wildly swinging skirts, rattling heels, lightning castanets, caught him up into the excitement of movement and colour and sound, a frenzied crescendo that ended abruptly, completely, jolting everyone into a shout of applause.

2

Reid slipped out of the courtyard into a room that was dark and silent. And oppressive; the collected heat of the day had been trapped under its heavily timbered ceiling. It was mostly used for storage: at one end, adjoining the wineshop itself, were grouped barrels, crates, sacks and cartons, their shapes vaguely outlined in the deep shadows. Someone had tried to cool the place and opened two of the shutters on the wall opposite the courtyard entrance, but the effort was only partially successful. Between the doorway where he stood and the barred windows, which were glassless, there was a hint of cross-ventilation, but the minute he started climbing the wooden stairs on his right, he felt the warm air close around him. It smelled of wine and wood, of leather and dust, with a touch of carnations from the perfume the girls liked to use. Their dressing-room was upstairs, part of a winding warren of little apartments. The men had their quarters on the ground floor, reached by a passage that began somewhere under the staircase; there, the smell of wine and wood and leather would be mixed with cigar smoke, hair oil, and lime cologne. To a stranger, the geography of this interior would be completely baffling. To Reid, it was a matter of fifteen wooden steps that hugged the wall all the way up to the landing, where there were two naked light bulbs, a venerable clock that had never yet failed in its timing, and two entrances. The one on the left to the girls’ side of the house; the one on the right to Tavita’s own corridor. It was this doorway he chose.

It was a narrow hallway, with several small rooms branching from it. Tavita’s receiving room, dressing-room, bathroom, special sitting-room were on one side, and naturally over-looked the courtyard. The other side of the corridor had a series of little square spaces no better than interior boxes, where clothes were made and stored and cleaned and pressed under old Magdalena’s supervision. She would be there now, in the biggest of the boxes, a small skylight open above her grey head, a radio picking up some Algerian station and its soft wailing music, working alone, ironing out frills and ruffles on Tavita’s change of costume, her shapeless black dress bent over bright colours, gnarled hands smoothing out fine silks with strange delicacy.

But as he passed her door, ready with a brief greeting and a friendly nod, he saw she was standing just inside the threshold, waiting. She put a finger to her lips, her other hand on his wrist, her eyes looked along the corridor as if she thought someone might be listening at its other end. So he took a step into the little room, carefully avoiding the wide hem of the white-and-yellow organza skirt that floated down from the ironing board, watching Magdalena’s pale, heavy, peasant face, with its tight lips and intense frown. She spoke in a deep hoarse whisper. “Important, this one. Very important. Tavita says you must get him away from here at once. Tonight. That’s what she says.”

Reid looked at her in surprise. In the six years Tavita and he had been running this little operation, there had never been any request like this. There never had been any urgency. Secrecy, certainly; that was a necessary part of security. A refugee from Cuba, smuggled out of Havana into Málaga, needed a place where he could find safe shelter until he could continue his journey to other parts of the country. There, relatives or friends would help him. (They had been contacted quietly, weeks and sometimes months before, to make sure that they were able and willing.) But in Málaga there were Castro agents and informers watching for stowaways; and the first day of freedom for a penniless man, often hungry and sick, could be a perilous one. There had been cases of political refugees, barely off the docks, who had been shanghaied right back to where they had come from. Others had thought they’d be safe if they could reach a police station or some official bureau, ask for asylum, be willing to face detention until their case would be judged. But it seemed impossible to prevent publicity: the news would leak out. Within hours, there would be a request from Havana for the man’s extradition: he was a murderer, an embezzler of union funds, a forger, a kidnapper and extortionist; full details of his crime—place, date, names of witnesses—to follow. And the details did follow, again within a few hours. “This man has to leave tonight?” Reid asked. “When did he arrive?”

“This morning.”

“The usual way?” Reid had worked out a simple—and so far dependable—method of bringing a refugee into El Fenicio. The first of them, six years ago, had been Tavita’s brother. El Fenicio had chosen itself, as it were, for the role of a safe house.

“No. He did not come from the docks. He came from Algeciras.”

“But how?”

Magdalena shook her head. She knew nothing. Tavita had given her the message for Señor Reid and she had passed it on. “He is dangerous, this one” was all she said. Her worst misgivings about helping any refugee had been fulfilled. She always had complained about the risks for Tavita. Not for el norteamericano; he could look after himself. So could Esteban. Even young Jaime. But Tavita? She could lose everything.

“Do you know this man?” Reid was watching her face closely.

She shook her head, pushed him out of her way as she reached over to switch on the iron. “Tavita knows of him,” she said. “He was a friend of her brother’s. That was many years ago. Here, in Málaga.”

“What is his name?”

Magdalena shrugged, tested the iron, began pressing a ruffle. She knew little, wanted to know even less. Whoever this man is, Reid thought, he really silences her. He reached out, gave her bent shoulders a reassuring pat, and then stepped into the corridor. Quickly, he walked its length, taking out his key to the sitting-room door. It was kept locked on the nights it held any special visitor. How many times had he come along here, just like this, in the last six years? No more than thirty. Some might think that a small achievement indeed, but it had been successful. Thirty men who would never have been given permission to leave Cuba had found their way out. And after tonight? Possibly this could be the end of the whole operation: the man behind this door hadn’t come here through regular channels, hadn’t even been expected. Yet he must have known the right identifications, or else Esteban would have played stupid, turned him away when he had arrived this morning. I like this as little as Magdalena, Reid thought as he turned the key in the lock and then knocked three times before he opened the door.

The room was in darkness except for a vertical strip of subdued light where the tall shutters had been left ajar. Down in the courtyard, Pablo’s heels were beating out a frenzied zapateado. The man who stood looking out at the balcony could not have heard Reid’s knocking against the collected noise, but he had sensed the door opening. He swung round on his heels, stepping aside from the band of light, and faced Reid.

“Close the shutters. Draw the curtains,” Reid said in Spanish. What kind of a fool am I dealing with? Had he actually been out there, on that balcony? Possibly it was safe enough, provided you moved slowly and kept well back in the shadows: it was partly recessed, and the iron railings and side pillars were thickly covered with climbing vines. Even so, there was a risk, and it irritated Reid.

“You close them,” the man told him in English. He stepped farther away, merging completely with the darkness.

Reid moved quickly, wasting no time on argument. He pushed the shutters gently together, fastened them securely; the strumming guitars, the stamping feet, the clapping hands, the cries of “Olé!” faded into the background. He caught the heavy folds of the long curtains, drew them close until their edges overlapped; the last vestiges of greyed light were blacked out. Behind him, the small lamp on the central table was switched on. Reid turned toward it, but the man was no longer there. He was now standing some six feet away, his right arm held stiffly, his eyes watching Reid’s hands. Reid kept his voice casual. “Were you out on that balcony?”

“It’s a good place to see what is going on.”

“It could be a foolish place, too.” Reid chose the nearest chair, sat down, crossed his legs, made no attempt to reach for his cigarettes.

“Did you see me out there?” The man slipped his throwing knife back into the cuff of his tight sleeve.

Reid shook his head. And was I supposed not to notice that knife? “You know, if I had come up here to kill you, I would have entered with a revolver pointed. I would have peppered the room in the direction you moved. There’s a good six-to-one chance that I would have got you.”

“A noisy method.”

“There are such things as silencers. Even without one of them, the noisy method might have seemed only part of the flamenco. Pablo’s heels rattle like a machine gun.”

The man sat down at the table. “Don’t be so sure you would have got me,” he said softly. “The light from the shutters reached the threshold of the door. I could see your feet—and your hands.”

So this was a type who never apologised, and if he explained it would be to show how right he was. Certainly, he wasn’t afraid of risks; but he calculated them. And his reflexes were remarkably quick. Physically, he was of medium height and weight, with even features, thick dark hair now greying, heavily tanned skin, pale lips, two deep furrows on either side of his mouth, expressionless brown eyes under heavy brows. He was dressed, surprisingly, in a neat summer suit of silver-grey, a cream silk shirt, a broadly knotted tie of almost the same colour. He was totally unlike any refugee who had ever emerged from a packing case in the hold of a cargo ship.

“You were late,” the man was saying, continuing his explanation.

Two minutes.”

“I saw you leave your table. Someone could have been waiting for you near the staircase. A matter of substitution, you understand.”

“Quite,” said Reid gravely. He repressed a smile. He had the feeling that this man might not appreciate any joke about conspiracy: he seemed to accept it as a natural way of life. Yes, Magdalena might have been right—this man could be trouble. “How did you know who I was?” He could risk taking out his cigarettes and lighter.

“Tavita pointed you out to me. Necessary, wouldn’t you say?”

“Certainly cautious.” Reid took a cigarette, was about to light it, remembered politeness, and rose to offer the pack. “Do you smoke?”

“I prefer cigars.”

“But not here,” Reid said quickly. “Tavita doesn’t smoke cigars.” He lit his own cigarette, sat down at the table with his hands well in view. The lighter was at his elbow. “The smell stays in a small room for days.”

“Does she smoke this brand of cigarette?” The man reached across the table, lifted the pack, examined it briefly, tossed it back.

“As a matter of fact, she does,” Reid said. “We are cautious, too, you see. I’m sorry we had to lock you in here, but that is also part of—Something wrong?” The stranger had stretched his arm across the table again, tapped Reid’s left hand.

“Only your watch. I’m amazed that a careful man lets it run slow.”

“I don’t think so.” If he’s interested in this watch, then let’s encourage him, Reid thought. Let’s keep his curiosity away from the lighter. Reid unfastened the watch from his wrist, wound it a little. “It usually keeps perfect time. Are you sure it isn’t your watch that is fast?”

“Perhaps. Certainly, it isn’t as elegant as that one. So very thin.”

“The newest fad. All face and no works. Like some people I know.”

“No works?”

“Hardly any. See?” Reid displayed the watch with an owner’s usual pride, let the man examine it closely. “I don’t suppose there are many of those for sale in Havana.”

“The first I’ve seen.”

Reid took the watch, strapped it back on his wrist. “Now, where were we? Oh, yes—caution. I was explaining why we had to keep you locked in here. But we don’t want any stranger opening that door and—”

“There is need for caution,” the coldly factual voice cut in. “I saw three men down in that courtyard, each of whom would have been quite capable of killing me. When I saw them, I thought that was why they had come here.”

Reid’s amusement ended. “If you’ve blown our little operation—”

“They may not have been following me. I doubt that. I have been excessively careful. They may only have been putting in time, spending it agreeably, normally; or they could have chosen to meet here where men of all types and nationalities can be found. We will watch them, of course—”

“Will we?”

“They are potentially dangerous, quite apart from me. They—”

“I’d prefer to hear about you. There are several questions. How did you get here, why did you come, who are you, where are you going, what relatives or friends have you in Spain?”

“Relatives? None. Friends? Tavita. Where am I going? To safety. Who am I, why did I come? The answer is the same: I am a defector.”

Reid stared at the quiet face opposite.

“And how did I get here? I’ve planned the journey for months.” He watched the American take off his jacket, throw it over a neighbouring chair, loosen his tie and the collar button of his shirt. “Yes, it is warm,” he said with his first smile, small and brief. But not for me, he seemed to be saying when he made no move to slip off his coat. Perhaps, thought Reid, he doesn’t want to show the gun he is carrying.

“Where did you start the journey?” Reid asked. Was this man really a defector? He could be Spanish Security. He could be a Castro spy. “And we’ll talk in Spanish now.”

“It was planned in Cuba, and started in Mexico when I went there on a special mission last month. From Mexico to Venezuela and then to Morocco. From Morocco to Spain, by the port of Algeciras—as a tourist. I even took an excursion across the bay to have a look at Gibraltar. Yesterday, I joined the tourists to see the beauties of Andalusia. I did not come into Málaga on that bus. I had a headache, a feeling of slight fever, so I left it when we stopped to make a brief visit to Torremolinos. What changes there are in that place! I knew it as a fishing village. Now there are a hundred hotels—like Miami’s. A stranger is not even noticed. And there are so many kinds of strangers, from the naked to the fully clothed. This morning, I came to Málaga by public bus—and then a short walk, and then a taxi; another stroll, another taxi. Oh, not to El Fenicio direct! Really, Señor Reid, you must understand that I do know this business. If you wonder how I arranged so many changes of clothing, passports, all I had to do was to have a small suitcase waiting for me in various cities. As I told you, I had plenty of time to arrange all that: six months of preparation, once I had decided on the plan. I used reputable hotels, American Express, Cook’s, even an airport in one place.”

“And if anyone had been curious and opened the suitcase stored with him?”

“Tragic for him. The locks could not be opened by any stranger without the case blowing up in his face.”

“And who left these cases for you to collect?”

“Various agents, helped by some sympathisers. They are accustomed to leaving suitcases and parcels for someone else to pick up. My department has quite a lot of experience in these matters. Don’t look so surprised. I have directed so many people to move between countries and continents that surely I know how to arrange my own travel.” He paused, smiled slightly again. “Do you understand all I’ve been saying? Or shall we go back into English? You now know that my accent is Spanish, and not Cuban or Puerto Rican or any other variety. Isn’t that so?”

That was so. But it was better to keep using Spanish; this man talked more freely in it. Reid ignored the smile. “You know,” he said softly, “you’re so damned smart, I don’t think you need anyone’s help to complete your escape.” And if you hadn’t dropped the word “defector”, he thought as he stared at those unreadable eyes, I wouldn’t have spent another two minutes on you; you aren’t the kind of refugee who needs any aid or comfort. What are you—defector, or agent for Castro’s Cuba? “In any case, there isn’t much you can expect here, except a bed and food and new clothes. That’s all Tavita ever provided, first to her brother, then to his friends, and then to friends of his friends. It has been mostly a family affair.”

“I know that. Don’t worry; I kept this ‘family affair’, as you call it, out of our files. It seemed to me, when I first discovered it, that it could have its uses. Tavita does owe me her brother’s life. But to be quite frank, I didn’t come here to ask Tavita’s help. I want yours.”

“Mine?”

“You have an organisation behind you. The CIA. That is what I need now. Fully, organised help.”