9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

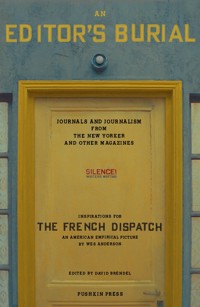

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Inspirations for Wes Anderson's The French Dispatch - brilliant essays by New Yorker luminaries that directly inspired the characters and settings of the film A glimpse of post-war France through the eyes and words of 14 (mostly) expatriate journalists including Mavis Gallant, James Baldwin, A.J. Liebling, S.N. Behrman, Luc Sante, Joseph Mitchell, and Lillian Ross; plus, portraits of their editors William Shawn and New Yorker founder Harold Ross. Together: they invented modern magazine journalism. Includes an introductory interview by Susan Morrison with Anderson about transforming fact into a fiction and the creation of his homage to these exceptional reporters.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

JOURNALS AND JOURNALISM FROM THE NEW YORKER AND OTHER MAGAZINES

EDITED BY DAVID BRENDEL

PUSHKIN PRESS

CONTENTS

THE PILOT LIGHT

(Or: Missing Something Left Behind)

A CONVERSATION BETWEEN WES ANDERSON AND SUSAN MORRISON

susan: Your movie “The French Dispatch” is a series of stories that are meant to be the articles in one issue of a magazine published by an American in Paris. When you were dreaming up the film, did you start with the character of Arthur Howitzer, Jr., the editor, or did you start with the stories?

wes: I read an interview with Tom Stoppard once where he said he began to realize—as people asked him over the years where the idea for one play or another came from—that it seems to have always been two different ideas for two different plays that he sort of smooshed together. It’s never one idea. It’s two. “The French Dispatch” might be three.

The first idea: I wanted to do an anthology movie. Just in general, an omnibus-type collection, without any specific stories in mind. (The two I love maybe the most: “The Gold of Naples” by de Sica and “Le Plaisir” by Max Ophuls.)

The second idea: I always wanted to make a movie about The New Yorker. The French magazine in the film obviously is not The New Yorker—but it was, I think, totally inspired by it. When I was in 11th grade, my homeroom was in the 8school library, and I sat in a chair where I had my back to everybody else, and I faced a wooden rack of what they labeled “periodicals”. One had drawings on the cover. That was unusual. I think the first story I read was by Ved Mehta. “Letter from Delhi.” I thought, “I have no idea what this is, but I’m interested.” But what I was most interested in were the short stories, because back then, I thought that was what I wanted to do—fiction. Write stories and novels and so on. When I went to the University of Texas in Austin, I used to look at old bound volumes of The New Yorker in the library, because you could find things like a J.D. Salinger story that had never been collected. Then I somehow managed to find out that UC Berkeley was getting rid of a set, forty years of bound New Yorkers, and I bought them for $600. I would also have my own new subscription copies bound (which is actually not a good way to preserve them). When the magazine put the whole archive online, I stopped paying to bind mine. But I still keep them. I have most every issue starting in the 1940s. Later, I found myself reading various writers’ accounts of life at The New Yorker—Brendan Gill, James Thurber, Ben Yagoda—and I got caught up in the whole aura of the thing. I also met Lillian Ross (with you), who, as we know, wrote about Truffaut and Hemingway and Chaplin for the magazine and was very close to Salinger, and so on and so forth.

The third idea: a French movie. I want to do one of those. An anthology, The New Yorker, and French. Three very broad notions. I think it sort of turned into a movie about what my friend and co-writer Hugo Guinness calls reverse 9emigration. He thinks Americans who go to Europe are reverse emigrating.

susan: When I saw the movie, I told you how much Lillian Ross, who died a couple of years ago, would have liked it. You said that Lillian’s first reaction would have been to demand, “Why France?”

wes: Well, I’ve had an apartment in Paris for I don’t know how many years. I’ve reverse emigrated. And in Paris, any time I walk down a street I don’t know well, it’s like going to the movies. It’s just entertaining. There’s also a sort of isolation living abroad, which can be good or it can be bad. It can be lonely, certainly. But you’re also always on a kind of adventure, which can be inspiring.

susan: Harold Ross, The New Yorker’s founding editor, was famous for saying that the history of New York is always written by out-of-towners. When you’re out of your element, or in another country, you have a different perspective. It’s as if a pilot light is always on.

wes: Yes! The pilot light is always on.

susan: In a foreign country, even just going into a hardware store can be like going to a museum.

wes: Buying a light bulb.

susan: Arthur Howitzer, Jr., the editor played by Bill Murray, gathers the best writers of his generation to staff his magazine, in Paris. They’re all expatriates, like you. In this book, you’ve gathered the best New Yorker writers, many of whom lived as expatriates in Paris. There is a line in the movie: “He received an Editor’s Burial,” and several of the pieces in this book are obituaries of Harold Ross.10

wes: Howitzer is based on Harold Ross, with a little bit of William Shawn, the magazine’s second editor, thrown in. Although they don’t really go together particularly. Ross had a great feeling for writers. It isn’t exactly respect. He values them, but he also thinks they’re lunatic children who have to be sort of manipulated or coddled. Whereas Shawn seems to have been the most gentle, respectful, encouraging master you could ever wish to have. We tried to mix in some of that.

susan: Both Ross and Shawn came from the Midwest; Howitzer is from Liberty, Kansas, right in the middle of America. He moves to France, to find himself, in a way, and he ends up creating a magazine that brings the world to Kansas.

wes: Originally, we were calling the editor character Liebling, not Howitzer, because the face I always pictured was A.J. Liebling’s. We tried to make Bill Murray sort of look like him, I think. Remember, he says he tricked his father into paying for his early sojourn in Paris by telling him he was thinking of marrying a good woman who was ten years older than he, although “Mother might think she is a bit fast…”

susan: There are lots of similarities between your Howitzer and Ross. Howitzer has a sign in his office that says, “No crying.” Ross made sure that there was no humming or singing or whistling in the office.

wes: They share a general grumpiness. What Thurber called Ross’s “God-how-I-pity-me!” moods.

susan: But you see a little bit of Shawn in Howitzer, as you mentioned. Shawn was formal and decorous, in contrast to Ross’s bluster. In the movie, when Howitzer tells the writer 11Herbsaint Sazerac, who Owen Wilson plays, that his article is “too seedy for decent people,” that’s very Shawn.

wes: I think that might be Ross, too! He was a prude, they say. For someone who could be extremely vulgar.

susan: In Thurber’s book “The Years with Ross,” which is excerpted here, there’s a funny part where Ross complains about a writer trying to sneak in a reference to menstruation, by having a woman character use the code phrase “I fell off the roof.” I’d never heard that euphemism! I had to look it up.

wes: “We can’t have that in the magazine.”

susan: Thurber also compared him to “a sleepless, apprehensive sea captain pacing the bridge, expecting any minute to run aground and collide with something nameless in a sudden fog.” You publishing a collection of stories as a companion piece to a movie feels like a literary version of a soundtrack. You can read this book the way you might read E.M. Forster before taking a trip to Florence. What made you decide to put this together?

wes: Two reasons.

One: our movie draws on the work and lives of specific writers. Even though it’s not an adaptation, the inspirations are specific and crucial to it. So, I wanted a way to say, “Here’s where it comes from.” I want to announce what it is. This book is almost a great big footnote.

Two: it’s an excuse to do a book that I thought would be really entertaining. These are writers I love and pieces I love. A person who is interested in the movie can read Mavis Gallant’s article about the student protests of 1968 12in here and discover there’s much more in it than in the movie. There’s a depth, in part because it’s much longer. It’s different, of course. Movies have their own thing. Frances McDormand’s character, Krementz, comes from Mavis Gallant but Lillian Ross also gets mixed into that character, too—and, I think, a bit of Frances herself. I once heard her say to a very snooty French waiter, “Kindly leave me my dignity.”

I remember reading Pauline Kael on John Huston’s movie of “The Dead.” She said Joyce’s story is a perfect masterpiece, but so is the movie. It has strengths that the story can’t have, simply because: actors. Great actors. There they are. Plus, they sing!

susan: Wouldn’t it be cool if every movie came with a suggested reading list?

wes: There are so many things we’re borrowing from. It’s nice to be able to introduce people to some of them.

susan: “The French Dispatch” is full of references to classic French cinema. There are lots of schoolboys in capes skittering around, like the ones in Truffaut and Jean Vigo movies.

wes: Yes! We wanted the movie to be full of all of the things we’ve loved in French movies. France, more or less, is where the cinema starts. Other than America, the country whose movies have meant the most to me is France. There are so many directors and so many stars and so many styles of French cinema. We sort of steal from Godard, Vigo, Truffaut, Tati, Clouzot, Duvivier, Jacques Becker. French noir movies, like “Le Trou” and “Grisbi” and “The Murderer Lives at Number 21.” We were stealing things very openly, so you 13really can kind of pinpoint something and find out exactly where it came from.

susan: When is the movie set? Some of it is 1965.

wes: I love Mavis Gallant’s piece about the events of May 1968, her journal. I knew that at least part of the movie had to take place around that time. I’m not entirely sure when the other parts happen! The magazine went from 1925 to 1975, so it is all during those 50 years, anyway.

susan: I see. I’d wondered if you have a particular affinity for the mid-sixties. You were born in 1969. There’s a psychological theory that says what we tend to be most nostalgic for is a period in time that is several years before our own birth—when our parents’ romance might have been at its peak. The technical term for the phenomenon is “cascading reminiscence bump.”

wes: I like that! I came across a good jargon-type phrase after we had made the movie. We do this thing where sometimes we have one person speak French, with subtitles, and the other person answers in English. I kept wondering, “Is this going to work?” Of course, we do it in real life all the time. The term I came across is: “non-accommodating bilingualism.” When people speak to each other, but don’t switch to the other person’s language. They stay in their own language, but they understand. They’re just completely non-accommodating.

susan: The Mavis Gallant story feels like the heart of the movie. Francine Prose, the novelist, is a big Gallant fan. She has described her as “at once scathing and endlessly tolerant and forgiving.” 14

wes: There’s nobody to lump her in with. Writing about May 1968, she has a totally independent point of view. It’s a foreigner’s perspective, but she’s very clear-sighted about all of it. Clarity and empathy. She went out every day, alone, in the middle of the chaos.

susan: Gallant was Canadian, which I think gave her a kind of double remove from America. Canadians in the United States have the pilot light, too. I think it’s why there are so many comedians from Canada. They have an outsider’s take. The great fiction writers from the American South also have it.

wes: She lived to be 91. In Paris. She lived in my neighborhood, less than a block away from our apartment, but I never met her. She died five years ago. I do feel like I almost knew her. I just missed her. It would have been very natural to me (at least, in my imagination) to say, “We have dinner with Mavis on Thursday.” So forceful and formidable a personality, and a very engaging person.

susan: This book includes a beautiful piece by Janet Flanner, about Edith Wharton living in Europe. She writes about how Wharton kept “repeatedly redomiciling herself,” and ended up a permanent “prose exile.” Is there a trace of Flanner in Krementz?

wes: Yes, there is some Janet Flanner in there. Flanner wrote so many pieces, sometimes topical in the most miniature ways. The smallest things happening in Paris in any given week. She wrote about May 1968, too. Her piece on it is good, and not so different from Mavis Gallant’s, but Flanner wasn’t standing out there with the kids in the streets so much. 15She was 76 then, and maybe a bit less sympathetic to the young people.

susan: Gallant is also sympathetic to their poor, worried parents. But there’s a toughness to her as well. You can tell that the Krementz character in the movie has sacrificed a lot in order to pursue her writing life. Her emotions only seem to surface as a result of tear gas.

wes: I have the sense that Gallant was one of those people who could be quite prickly. From what I’ve read about her, she seems like she was a wonderful person to have dinner with, unless somebody said something stupid or ungenerous, in which case things might turn dark. I think she might have been someone who, in certain situations, could not stop herself from eviscerating a person who had offended her principles. She was not going to stand for nonsense.

susan: You mention Lillian Ross, too.

wes: Yes, as you know, Lillian had a way of poking right through something, needling, with a deceptively curious look on her face. I first met her when Anjelica Huston brought her to the set of “The Royal Tenenbaums.” You were there with her.

susan: Yes, at that glass house designed by Paul Rudolph, in the East Fifties. Ben Stiller’s character lived there in the movie.

wes: I said to Anjelica, “Lillian Ross is going to come visit? That’s incredible.” She said, “Yes. Be careful.” Anjelica has so much family history with Lillian starting, obviously, when she wrote “Picture.” Anjelica and Lillian were great friends.

susan: In your movie, the showdown between Krementz and Juliet, one of the revolutionary teenagers, is intense. 16

wes: Krementz scolds the kids, but she admires them. There are lines in Frances’s dialogue, as Krementz, that are taken directly from the Gallant piece: “The touching narcissism of the young.” There are some non-sequiturs in the script, some things totally unrelated to the action, that I put in only because I wanted to use some of Mavis Gallant’s actual sentences. Timothée Chalamet’s character, the teen revolutionary, says, at one point, “I’ve never read my mother’s books.” In Gallant’s piece, she says that about the daughter of her friend. Also, “I wonder if she knows how brave her father was in the last war?” Just to call it “the last war”—our most recent world war—maybe we wouldn’t say it that way now. I mean, is there another one coming? We don’t know.

susan: In the movie, the student protest begins because the boys want to be allowed into the girls’ dormitories. During the screening, I remember thinking, “Oh, that’s such a Wes Anderson version of what would spark a student uprising!” Then when I read up on the history of the conflict, I saw that it actually was the original issue.

wes: Daniel Cohn-Bendit in Nanterre. That was one of his demands. Maybe the larger point was, “We don’t want to be treated like children,” but literally calling for the right of free access to the girls’ dormitory for all male students? The sentence sounded so funny to me. And then the revolutionary spirit spreads through every part of French society and ends up having nothing to do with girls’ dormitories. By the end, no one can even say what the protests are about anymore. That’s what Mavis Gallant captures so well, that people can’t quite fully process what’s happening and why.17

susan: It’s a world turned upside down. There are workers on strike, professors who want a better deal, people angry about the Vietnam war.

wes: And Gallant is trying to figure out: what can end this chaos, when the protesters can no longer clearly articulate what they’re fighting for? She asks the kids, and the answer seems to be: an honest life, a clean life, a clean and honest France.

susan: It reminds me of something that William Maxwell, Gallant’s New Yorker editor, once said about her stories: “The older I get the more grateful I am not to be told how everything comes out.” You know, the film captures an interesting aspect of the writer–editor relationship. When a writer turns in a new story, it’s like an offering to the editor. There’s something intimate about it. Howitzer and his magazine function as a family for all of these isolated expatriates. Krementz, in particular, seems to use the concept of “journalistic neutrality” as a cover for loneliness. What does the chef say at the end?

wes: Yes, Nescaffier, the cook played by the great Stephen Park, describes his life as a foreigner: “Seeking something missing, missing something left behind.”

susan: That runs through all of these pieces, and also through the lives of all of these writers. People have been calling the movie a love letter to journalists. That’s encouraging, given that we live in a time when journalists are being called the enemies of the people.

wes: That’s what our colleagues at the studio call it. I might not use that exact turn of phrase, just because it’s not a love letter. It’s a movie. But it’s about journalists I have loved, 18journalists who have meant something to me. For the first half of my life I thought of The New Yorker as primarily a place to read fiction, and the movie we made is all fiction. None of the journalists in the movie actually existed, and the stories are all made up. So I’ve made a fiction movie about reportage, which is odd.

susan: The movie is like a big otherworldly cocktail party where mashups of real people, like James Baldwin and Mavis Gallant and Janet Flanner and A.J. Liebling, are chatting with subjects of New Yorker articles, like Rosamond Bernier, the art lecturer, who was profiled by Calvin Tomkins. In the story about the artist in prison, Moses Rosenthaler, Bernier is the inspiration for the character that Tilda Swinton plays, J.K.L. Berenson. Or Joseph Duveen, the eccentric buccaneer art dealer played by Adrien Brody in the same story.

wes: Duveen sold Old Masters and Renaissance paintings from Europe to American tycoons and robber barons. The painters were all dead, but we have a living painter, Rosenthaler. So that relationship comes from somewhere else. And so does the painter himself. Tilda’s character, inspired by Rosamond Bernier, ends up being sort of the voice of S.N. Behrman, the New Yorker writer who profiled Duveen. It’s a lot of mixing.

susan: Duveen is such a modern character. He seems like somebody who works for Mike Ovitz.

wes: Or he could’ve been a mentor to Ovitz. Or Larry Gagosian. We have a rich art-collecting lady from Kansas named “Maw” Clampette, who is played by Lois Smith. In the Duveen book, there is a woman, a wife of one of the 19tycoons, I can’t remember which one, who talks a bit like a hillbilly. We based “Maw” Clampette’s manner of speech on hers, maybe. But the character was actually inspired by Dominique de Menil, who lived in my hometown of Houston. She’s the most refined kind of French Protestant woman, a fantastically interesting art collector, who came to Texas with her husband and together they shared their art and their sort of vision. Her eye.

susan: I guess “Clampette” is a reference to “The Beverly Hillbillies?”

wes: I feel yes.

susan: The character of Roebuck Wright, who Jeffrey Wright plays in the last story, about the police commissioner’s chef, is another inspired composite. He is a gay, African American gourmand, and he seems to be one part A.J. Liebling and one part James Baldwin, who moved to Paris to get away from the racism of the United States. That’s a daring combination.

wes: Hopefully people won’t consider it a daring, ill-advised combination. With every character in the movie there’s a mixture of inspirations. I always carry a little notebook with me to write down ideas. I don’t know what I am going to do with them or what they’re going to end up being. But sometimes I jot down names of actors who I want to work with. Jeffrey Wright and Benicio Del Toro have been at the top of this list that I’ve been keeping for years. I wanted to write a part for Jeffrey and a part for Benicio. When we were thinking about the character of Roebuck Wright, we always had a bit of Baldwin in him. I’d read “Giovanni’s Room” 20and a few essays. But, when I saw Raoul Peck’s Baldwin movie, I was so moved and so interested in him. I watched the Cambridge Union debate between Baldwin and William F. Buckley from 1965. It’s not just that Baldwin’s words are so spectacularly eloquent and insightful. It’s also him, his voice, his personality. So: we were thinking about the way he talked, and we also thought about the way Tennessee Williams talked, and Gore Vidal’s way of talking. We mixed in aspects of those writers, too. Plus Liebling. Why? I have no idea. They joined forces.

susan: There’s a line from Baldwin’s piece, “Equal in Paris,” which reads like an epigraph for your movie. He writes, “the French personality had seemed so large and free… but if it was large, it was also inflexible, and, for the foreigner, full of strange, high, dusty rooms which could not be inhabited.”

wes: If you’re an American in France for a period of time, you know that feeling. It’s kind of a complicated metaphor. When I read that, I do think, “I know exactly what you mean.”

susan: One of the things Howitzer is always telling his writers is “Make it sound like you wrote it that way on purpose.” That reminds me of what Calvin Trillin says about Joseph Mitchell’s style. He says that Mitchell was able to get the “marks of writing” off of his pieces. Where did you get your line?

wes: I guess I was thinking about how there’s an almost infinite number of ways to write something well. Each writer has a completely different approach. How can you give the same advice to Joseph Mitchell that you would give to George Trow? Two people doing something so completely different. 21I was trying to come up with a funny way to say: please, attempt to accomplish your intention perfectly. I don’t know if that’s very useful advice to a writer.

susan: It’s good. Basically, it’s just, “Make it sound confident.”

wes: When you’re making a movie, you want to feel like you can take it in any direction, you can experiment, as long as it in the end feels like this is what it’s meant to be, and it has some authority.

susan: There’s an unnamed writer mentioned in the movie, described as “the best living writer in terms of sentences per minute.” Who is that a reference to?

wes: Liebling said, of himself, “I can write better than anybody who can write faster, and I can write faster than anybody who can write better.” We shortened it so that it would work in the montage. There’s maybe a little bit of Ben Hecht, too. There are a few other writers mentioned in passing. We have the faintest reference to Ved Mehta, who I’ve always loved, especially “The Photographs of Chachaji.” The character in the movie has an amanuensis. I learned that word from him, I think!

susan: And then the “cheery writer” who didn’t write anything for decades, played by Wally Wolodarsky? That’s Joe Mitchell, right?

wes: That’s Mitchell, except Mitchell had an unforgettable body of work before he stopped writing. With our guy, that doesn’t appear to be the case. He never wrote anything in the first place.

susan: That’s wonderfully Dada. I became friendly with Joe Mitchell late in his life. I was trying to get him to write 22something for me at The New York Observer. He hadn’t published in thirty years. He never turned anything in, but we talked on the phone every week and he would sing sea shanties to me.

wes: The character that Owen Wilson plays, Sazerac, is meant to be a bit like Mitchell. He writes about the seamy side of the city. And Sazerac is on a bicycle the whole time, which is maybe a nod to Bill Cunningham, but also Owen is always on a bike in real life. It wouldn’t be unheard of, if you were in Berlin or Tokyo or someplace, to see Owen Wilson riding up on a bicycle. Sazerac also owes a major debt to Luc Sante, too, because we took so much atmosphere from his book “The Other Paris.” He is Mitchell and Luc Sante and Owen.

susan: The Sazerac mashup is especially inventive. Joseph Mitchell was the original lowlife reporter. He went out to the docks and slums and wandered around talking to people. And Luc, whose books, “Low Life,” about the historical slums of New York, and “The Other Paris,” about the Paris underworld of the nineteenth century, is more of a literary academic. He finds his gems in the library and the flea market.

wes: Mitchell is more, like, “I talked to the man who was opening the oysters, and he told me this story.”

susan: Mitchell is what we call a shoe-leather reporter. You’ve included Mitchell’s magnum opus on rats in this book. There’s a line in it, about a rat stealing an egg, that feels like it could be a sequence in one of your movies: “A small rat would straddle an egg and clutch it in his four paws. When 23he got a good grip on it, he’d roll over on his back and a bigger rat would grab him by the tail and drag him across the floor to a hole in the baseboard.”

wes: Maybe Mitchell picked that up talking to an exterminator. I remember an image from the piece about how, when it starts to get cold in the fall, you could see the rats running across Central Park West in hordes, into the basements of buildings, leaving the park for the summer. It was the first thing by Mitchell I ever read.

susan: Have you been filing away these New Yorker pieces for years?

wes: I don’t know. Not deliberately. I knew which writers I wanted to refer to. At the end of the movie, before the credits, there is a list of writers we dedicate the movie to. Some of the people on the list, like St. Clair McKelway and Wolcott Gibbs, or E.B. White and Katharine White, are there not because their stories are in the movie, but because of their roles in making The New Yorker what it is. For defining the voice and tone of the magazine.

susan: Usually when New Yorker writers are depicted in movies, they’re portrayed as just a bunch of antic cut-ups, rather than people who are devoted to their work.

wes: It’s harder to do a movie about real people, when you already know who each person is meant to be—like the members of the Algonquin Round Table—and each actor has to then embody somebody who already exists. There’s a little more freedom when you make the people up.

susan: Have you ever made a movie before that drew on such a rich reservoir of material for inspiration? 24

wes: Not this much stuff. This one’s been brewing for years and years and years. By the time I started working with Jason Schwartzman and Roman Coppola, though, it sorted itself out pretty quickly.

susan: What order did you write them in?

wes: The last story we wrote was the Roebuck Wright one, and we wrote it fast. The story about the painter, I must’ve had something on paper about that for at least ten years. The Berenson character that Tilda Swinton plays wasn’t in it yet, though.

susan: Talk about the names of the two cities: Liberty, Kansas and Ennui-sur-Blasé.

wes: I think Jason just said it out loud: “Ennui-sur-Blasé.” We wanted them to be sister cities. Liberty, well, that’s got an American ring to it.

susan: What do you think the French will make of the movie?

wes: I have no idea. We do have a lot of French actors. It’s kind of a confection, a fantasy, but it still needs to feel like the real version of a fantasy. It has to feel like its roots are believable. I think it’s pretty clear the movie is set in a foreigner’s idea of France. I always think of Wim Wenders’ version of America, which I love. “Paris, Texas,” and also the photographs that he used to take in the West. It’s just that one particular individual German’s view of America. People don’t necessarily like it when you invade their territory, even respectfully, but maybe they start to appreciate it when they see how much you love the place. But then again: who knows?

THE YEARS WITH ROSS

James Thurber

1957

Harold ross died December 6, 1951, exactly one month after his fifty-ninth birthday. In November of the following year the New Yorker entertained the editors of Punch and some of its outstanding artists and writers. I was in Bermuda and missed the party, but weeks later met Rowland Emett for lunch at the Algonquin. “I’m sorry you didn’t get to meet Ross,” I began as we sat down. “Oh, but I did,” he said. “He was all over the place. Nobody talked about anybody else.”

Ross is still all over the place for many of us, vitally stalking the corridors of our lives, disturbed and disturbing, fretting, stimulating, more evident in death than the living presence of ordinary men. A photograph of him, full face, almost alive with a sense of contained restlessness, hangs on a wall outside his old office. I am sure he had just said to the photographer, “I haven’t got time for this.” That’s what he said, impatiently, to anyone—doctor, lawyer, tax man—who interrupted, even momentarily, the stream of his dedicated energy. Unless a meeting, conference, or consultation touched somehow upon the working of his magazine, he began mentally pacing.

I first met Harold Ross in February, 1927, when his weekly was just two years old. He was thirty-four and I was thirty-two. 26The New Yorker had printed a few small pieces of mine, and a brief note from Ross had asked me to stop in and see him some day when my job as a reporter for the New York EveningPost chanced to take me uptown. Since I was getting only forty dollars a week and wanted to work for the New Yorker, I showed up at his office the next day. Our meeting was to become for me the first of a thousand vibrant memories of this exhilarating and exasperating man.

You caught only glimpses of Ross, even if you spent a long evening with him. He was always in mid-flight, or on the edge of his chair, alighting or about to take off. He won’t sit still in anybody’s mind long enough for a full-length portrait. After six years of thinking about it, I realized that to do justice to Harold Ross I must write about him the way he talked and lived—leaping from peak to peak. What follows here is a monologue montage of that first day and of half a dozen swift and similar sessions. He was standing behind his desk, scowling at a manuscript lying on it, as if it were about to lash out at him. I had caught glimpses of him at the theater and at the Algonquin and, like everybody else, was familiar with the mobile face that constantly changed expression, the carrying voice, the eloquent large-fingered hands that were never in repose, but kept darting this way and that to emphasize his points or running through the thatch of hair that stood straight up until Ina Claire said she would like to take her shoes off and walk through it. That got into the gossip columns and Ross promptly had his barber flatten down the pompadour.

He wanted, first of all, to know how old I was, and when I told him it set him off on a lecture. “Men don’t mature in this 27country, Thurber,” he said. “They’re children. I was editor of the Stars and Stripes when I was twenty-five. Most men in their twenties don’t know their way around yet. I think it’s the goddam system of women schoolteachers.” He went to the window behind his desk and stared disconsolately down into the street, jingling coins in one of his pants pockets. I learned later that he made a point of keeping four or five dollars’ worth of change in this pocket because he had once got stuck in a taxi, to his vast irritation, with nothing smaller than a ten-dollar bill. The driver couldn’t change it and had to park and go into the store for coins and bills, and Ross didn’t have time for that.

I told him that I wanted to write, and he snarled, “Writers are a dime a dozen, Thurber. What I want is an editor. I can’t find editors. Nobody grows up. Do you know English?” I said I thought I knew English, and this started him off on a subject with which I was to become intensely familiar. “Everybody thinks he knows English,” he said, “but nobody does. I think it’s because of the goddam women schoolteachers.” He turned away from the window and glared at me as if I were on the witness stand and he were the prosecuting attorney. “I want to make a business office out of this place, like any other business office,” he said. “I’m surrounded by women and children. We have no manpower or ingenuity. I never know where anybody is, and I can’t find out. Nobody tells me anything. They sit out there at their desks, getting me deeper and deeper into God knows what. Nobody has any self-discipline, nobody gets anything done. Nobody knows how to delegate anything. What I need is a man who can sit at a central desk and make this place operate like a business office, keep track of things, find out where people 28are. I am, by God, going to keep sex out of this office—sex is an incident. You’ve got to hold the artists’ hands. Artists never go anywhere, they don’t know anybody, they’re antisocial.”

Ross was never conscious of his dramatic gestures, or of his natural gift of theatrical speech. At times he seemed to be on stage, and you half expected the curtain to fall on such an agonized tagline as “God, how I pity me!” Anthony Ross played him in Wolcott Gibbs’s comedy Season in the Sun, and an old friend of his, Lee Tracy, was Ross in a short-lived play called Metropole, written by a former secretary of the editor. Ross sneaked in to see the Gibbs play one matinee, but he never saw the other one. I doubt if he recognized himself in the Anthony Ross part. I sometimes think he would have disowned a movie of himself, sound track and all.

He once found out that I had done an impersonation of him for a group of his friends at Dorothy Parker’s apartment, and he called me into his office. “I hear you were imitating me last night, Thurber,” he snarled. “I don’t know what the hell there is to imitate—go ahead and show me.” All this time his face was undergoing its familiar changes of expression and his fingers were flying. His flexible voice ran from a low register of growl to an upper register of what I can only call Western quacking. It was an instrument that could give special quality to such Rossisms as “Done and done!” and “You have me there!” and “Get it on paper!” and such a memorable tagline as his farewell to John McNulty on that writer’s departure for Hollywood: “Well, God bless you, McNulty, goddam it.”

Ross was, at first view, oddly disappointing. No one, I think, would have picked him out of a line-up as the editor of the New 29Yorker. Even in a dinner jacket he looked loosely informal, like a carelessly carried umbrella. He was meticulous to the point of obsession about the appearance of his magazine, but he gave no thought to himself. He was usually dressed in a dark suit, with a plain dark tie, as if for protective coloration. In the spring of 1927 he came to work in a black hat so unbecoming that his secretary, Elsie Dick, went out and bought him another one. “What became of my hat?” he demanded later. “I threw it away,” said Miss Dick. “It was awful.” He wore the new one without argument. Miss Dick, then in her early twenties, was a calm, quiet girl, never ruffled by Ross’s moods. She was one of the few persons to whom he ever gave a photograph of himself. On it he wrote, “For Miss Dick, to whom I owe practically everything.” She could spell, never sang, whistled, or hummed, knew how to fend off unwanted visitors, and had an intuitive sense of when the coast was clear so that he could go down in the elevator alone and not have to talk to anybody, and these things were practically everything.

In those early years the magazine occupied a floor in the same building as the Saturday Review of Literature on West 45th Street. Christopher Morley often rode in the elevator, a tweedy man, smelling of pipe tobacco and books, unmistakably a literary figure. I don’t know that Ross ever met him. “I know too many people,” he used to say. The editor of the New Yorker, wearing no mark of his trade, strove to be inconspicuous and liked to get to his office in the morning, if possible, without being recognized and greeted.

From the beginning Ross cherished his dream of a Central Desk at which an infallible omniscience would sit, a dedicated 30genius, out of Technology by Mysticism, effortlessly controlling and coördinating editorial personnel, contributors, office boys, cranks and other visitors, manuscripts, proofs, cartoons, captions, covers, fiction, poetry, and facts, and bringing forth each Thursday a magazine at once funny, journalistically sound, and flawless. This dehumanized figure, disguised as a man, was a goal only in the sense that the mechanical rabbit of a whippet track is a quarry. Ross’s mind was always filled with dreams of precision and efficiency beyond attainment, but exciting to contemplate.

This conception of a Central Desk and its superhuman engineer was the largest of half a dozen intense preoccupations. You could see it smoldering in his eyes if you encountered him walking to work, oblivious of passers-by, his tongue edging reflectively out of the corner of his mouth, his round-shouldered torso seeming, as Lois Long once put it, to be pushing something invisible ahead of him. He had no Empire Urge, unlike Henry Luce and a dozen other founders of proliferating enterprises. He was a one-magazine, one-project man. (His financial interest in Dave Chasen’s Hollywood restaurant was no more central to his ambition than his onetime investment in a paint-spraying machine—I don’t know whatever became of that.) He dreamed of perfection, not of power or personal fortune. He was a visionary and a practicalist, imperfect at both, a dreamer and a hard worker, a genius and a plodder, obstinate and reasonable, cosmopolitan and provincial, wide-eyed and world-weary. There is only one word that fits him perfectly, and the word is Ross.

When I agreed to work for the New Yorker as a desk man, it was with deep misgivings. I felt that Ross didn’t know, and 31wasn’t much interested in finding out, anything about me. He had persuaded himself, without evidence, that I might be just the wonder man he was looking for, a mistake he had made before and was to make again in the case of other newspapermen, including James M. Cain, who was just about as miscast for the job as I was. Ross’s wishful thinking was, it seems to me now, tinged with hallucination. In expecting to find, in everybody that turned up, the Ideal Executive, he came to remind me of the Charlie Chaplin of The Gold Rush, who, snowbound and starving with another man in a cabin teetering on the edge of a cliff, suddenly beholds his companion turning into an enormous tender spring chicken, wonderfully edible, supplied by Providence. “Done and done, Thurber,” said Ross. “I’ll give you seventy dollars a week. If you write anything, goddam it, your salary will take care of it.” Later that afternoon he phoned my apartment and said, “I’ve decided to make that ninety dollars a week, Thurber.” When my first check came through it was for one hundred dollars. “I couldn’t take advantage of a newspaperman,” Ross explained.

By the spring of 1928 Ross’s young New Yorker was safely past financial and other shoals that had menaced its launching, skies were clearing, the glass was rising, and everybody felt secure except the skipper of the ship. From the first day I met him till the last time I saw him, Ross was like a sleepless, apprehensive sea captain pacing the bridge, expecting any minute to run aground, collide with something nameless in a sudden fog, or find his vessel abandoned and adrift, like the Mary Celeste. When, at the age of thirty-two, Ross had got his magazine afloat with the aid of Raoul Fleischmann and a handful of associates, the 32proudest thing he had behind him was his editorship of the Stars and Stripes in Paris from 1917 to 1919.

As the poet is born, Ross was born a newspaperman. “He could not only get it, he could write it,” said his friend Herbert Asbury. Ross got it and wrote it for seven different newspapers before he was twenty-five years old, beginning as a reporter for the Salt Lake City Tribune when he was only fourteen. One of his assignments there was to interview the madam of a house of prostitution. Always self-conscious and usually uncomfortable in the presence of all but his closest women friends, the young reporter began by saying to the bad woman (he divided the other sex into good and bad), “How many fallen women do you have?”

Later he worked for the Marysville (California) Appeal, Sacramento Union, Panama Star and Herald, New Orleans Item, Atlanta Journal, and San Francisco Call.

The wanderer—some of his early associates called him “Hobo”—reached New York in 1919 and worked for several magazines, including Judge and the American Legion Weekly, his mind increasingly occupied with plans for a new kind of weekly to be called the New Yorker. It was born at last, in travail and trauma, but he always felt uneasy as the R of the F-R Publishing Company, for he had none of the instincts and equipment of the businessman except the capacity for overwork and overworry. In his new position of high responsibility he soon developed the notion, as Marc Connelly has put it, that the world was designed to wear him down. A dozen years ago I found myself almost unconsciously making a Harold Ross out of one King Clode, a rugged pessimist in a fairy tale I was writing. At one 33point the palace astronomer rushed into the royal presence saying, “A huge pink comet, Sire, just barely missed the earth a little while ago. It made an awful hissing sound, like hot irons stuck in water.” “They aim these things at me!” said Clode. “Everything is aimed at me.” In this fantasy Clode pursues a fabulously swift white deer which, when brought to bay, turns into a woman, a parable that parallels Ross’s headlong quest for the wonder man who invariably turned into a human being with feet of clay, as useless to Ross as any enchanted princess.

Among the agencies in mischievous or malicious conspiracy to wear Ross down were his own business department (“They’re not only what’s the matter with me, they’re what’s the matter with the country”), the state and federal tax systems, women and children (all the females and males that worked for him), temperament and fallibility in writers and artists, marriages and illnesses—to both of which his staff seemed especially susceptible—printers, engravers, distributors, and the like, who seemed to aim their strikes and ill-timed holidays directly at him, and human nature in general.

Harold Wallace Ross, born in Aspen, Colorado, in 1892, in a year and decade whose cradles were filled with infants destined to darken his days and plague his nights, was in the midst of a project involving the tearing down of walls the week I started to work. When he outlined his schemes of reconstruction, it was often hard to tell where rationale left off and mystique began. (How he would hate those smart-aleck words.) He seemed to believe that certain basic problems of personnel might just possibly be solved by some fortuitous rearrangement of the offices. Time has mercifully foreshortened the months of my ordeal 34as executive editor, and only the highlights of what he called “practical matters” still remain. There must have been a dozen Through the Looking Glass conferences with him about those damned walls. As an efficiency expert or construction engineer, I was a little boy with an alarm clock and a hammer, and my utter incapacity in such a role would have been apparent in two hours to an unobsessed man. I took to drinking Martinis at lunch to fortify myself for the tortured afternoons of discussion.

“Why don’t we put the walls on wheels?” I demanded one day. “We might get somewhere with adjustable walls.”

Ross’s eyes lighted gloomily, in an expression of combined hope and dismay which no other face I have known could duplicate. “The hell with it,” he said. “You could hear everybody talking. You could see everybody’s feet.”

He and I worked seven days a week, often late into the night, for at least two months, without a day off. I began to lose weight, editing factual copy for sports departments and those dealing with new apartments, women’s fashions, and men’s wear.

“Gretta Palmer keeps using words like introvert and extrovert,” Ross complained one day. “I’m not interested in the housing problems of neurotics. Everybody’s neurotic. Life is hard, but I haven’t got time for people’s personal troubles. You’ve got to watch Woollcott and Long and Parker—they keep trying to get double meanings into their stuff to embarrass me. Question everything. We damn near printed a news-break about a girl falling off the roof. That’s feminine hygiene, somebody told me just in time. You probably never heard the expression in Ohio.”

“In Ohio,” I told him, “we say the mirror cracked from side to side.” 35

“I don’t want to hear about it,” he said.

He nursed an editorial phobia about what he called the functional: “bathroom and bedroom stuff.” Years later he deleted from a Janet Flanner “London Letter” a forthright explanation of the long nonliquid diet imposed upon the royal family and important dignitaries during the coronation of George VI. He was amused by the drawing of a water plug squirting a stream at a small astonished dog, with the caption “News,” but he wouldn’t print it. “So-and-so can’t write a story without a man in it carrying a woman to a bed,” he wailed. And again, “I’ll never print another O’Hara story I don’t understand. I want to know what his people are doing.” He was depressed for weeks after the appearance of a full-page Arno depicting a man and a girl on a road in the moonlight, the man carrying the back seat of an automobile. “Why didn’t somebody tell me what it meant?” he asked. Ross had insight, perception, and a unique kind of intuition, but they were matched by a dozen blind spots and strange areas of ignorance, surprising in a virile and observant reporter who had knocked about the world and lived two years in France. There were so many different Rosses, conflicting and contradictory, that the task of drawing him in words sometimes appears impossible, for the composite of all the Rosses should produce a single unmistakable entity: the most remarkable man I have ever known and the greatest editor. “If you get him down on paper,” Wolcott Gibbs once warned me, “nobody will believe it.”

I made deliberate mistakes and let things slide as the summer wore on, hoping to be demoted to rewriting “Talk of the Town,” with time of my own in which to write “casuals.” That was Ross’s word for fiction and humorous pieces of all kinds. Like 36“Profile” and “Reporter at Large” and “Notes and Comment,” the word “casual” indicated Ross’s determination to give the magazine an offhand, chatty, informal quality. Nothing was to be labored or studied, arty, literary, or intellectual. Formal short stories and other “formula stuff” were under the ban. Writers were to be played down; the accent was on content, not personalities. “All writers are writer-conscious,” he said a thousand times.

One day he came to me with a letter from a men’s furnishing store which complained that it wasn’t getting fair treatment in the “As to Men” department. “What are you going to do about that?” he growled. I swept it off my desk onto the floor. “The hell with it,” I said. Ross didn’t pick it up, just stared at it dolefully. “That’s direct action, anyway,” he said. “Maybe that’s the way to handle grousing. We can’t please everybody.” Thus he rationalized everything I did, steadfastly refusing to perceive that he was dealing with a writer who intended to write or to be thrown out. “Thurber has honesty,” he told Andy White, “admits his mistakes, never passes the buck. Only editor with common sense I’ve ever had.”

I finally told Ross, late in the summer, that I was losing weight, my grip, and possibly my mind, and had to have a rest. He had not realized I had never taken a day off, even Saturday or Sunday. “All right, Thurber,” he said, “but I think you’re wearing yourself down writing pieces. Take a couple of weeks, anyway. Levick can hold things down while you’re gone. I guess.”

It was, suitably enough, a dog that brought Ross and me together out of the artificiality and stuffiness of our strained and mistaken relationship. I went to Columbus on vacation and 37took a Scottie with me, and she disappeared out there. It took me two days to find her, with the help of newspaper ads and the police department. When I got back to the New Yorker, two days late, Ross called me into his office about seven o’clock, having avoided me all day. He was in one of his worst God-how-I-pity-me moods, a state of mind often made up of monumentally magnified trivialities. I was later to see this mood develop out of his exasperation with the way Niven Busch walked, or the way Ralph Ingersoll talked, or his feeling that “White is being silent about something and I don’t know what it is.” It could start because there weren’t enough laughs in “Talk of the Town,” or because he couldn’t reach Arno on the phone, or because he was suddenly afflicted by the fear that nobody around the place could “find out the facts.” (Once a nerve-racked editor yelled at him, “Why don’t you get Westinghouse to build you a fact-finding machine?”)

This day, however, the Ossa on the Pelion of his molehill miseries was the lost and found Jeannie. Thunder was on his forehead and lightning in his voice. “I understand you’ve overstayed your vacation to look for a dog,” he growled. “Seems to me that was the act of a sis.” (His vocabulary held some quaint and unexpected words and phrases out of the past. “They were spooning,” he told me irritably about some couple years later, and, “I think she’s stuck on him.”) The word sis, which I had last heard about 1908, the era of skidoo, was the straw that shattered my patience. Even at sixty-four my temper is precarious, but at thirty-two it had a hair trigger.

The scene that followed was brief, loud, and incoherent. I told him what to do with his goddam magazine, that I was 38through, and that he couldn’t call me a sis while sitting down, since it was a fighting word. I offered to fight him then and there, told him he had the heart of a cast-iron lawn editor, and suggested that he call in one of his friends to help him. Ross hated scenes, physical violence or the threat of it, temper and the unruly.

“Who would you suggest I call in?” he demanded, the thunder clearing from his brow.

“Alexander Woollcott!” I yelled, and he began laughing.

His was a wonderful, room-filling laugh when it came, and this was my first experience of it. It cooled the air like summer rain. An hour later we were having dinner together at Tony’s after a couple of drinks, and that night was the beginning of our knowledge of each other underneath the office make-up, and of a lasting and deepening friendship. “I’m sorry, Thurber,” he said. “I’m married to this magazine. It’s all I think about. I knew a dog I liked once, a shepherd dog, when I was a boy. I don’t like dogs as such, though, and I’ll, by God, never run a department about dogs—or about baseball, or about lawyers.” His eyes grew sad; then he gritted his teeth, always a sign that he was about to express some deep antipathy, or grievance, or regret. “I’m running a column about women’s fashions,” he moaned, “and I never thought I’d come to that.” I told him the “On and Off the Avenue” department was sound, a word he always liked to hear, but used sparingly. It cheered him up.

It wasn’t long after that fateful night that Ross banged into my office one afternoon. He paced around for a full minute without saying anything, jingling the coins in his pocket. “You’ve been 39writing,” he said finally. “I don’t know how in hell you found time to write. I admit I didn’t want you to. I could hit a dozen writers from here with this ash tray. They’re undependable, no system, no self-discipline. Dorothy Parker says you’re a writer, and so does Baird Leonard.” His voice rose to its level of high decision. “All right then, if you’re a writer, write! Maybe you’ve got something to say.” He gave one of his famous prolonged sighs, an agonized protesting acceptance of a fact he had been fighting.

From then on I was a completely different man from the one he had futilely struggled to make me. No longer did he tell White that I had common sense. I was a writer now, not a hand-holder of artists, but a man who needed guidance. Years later he wrote my wife a letter to which he appended this postscript: “Your husband’s opinion on a practical matter of this sort would have no value.” We never again discussed tearing down walls, the Central Desk, the problems of advertisers, or anything else in the realm of the practical. If a manuscript was lost, “Thurber lost it.” Once he accused me of losing a typescript that later turned up in an old briefcase of his own. This little fact made no difference. “If it hadn’t been there,” he said, “Thurber would have lost it.” As I become more and more “productive,” another of his fondest words, he became more and more convinced of my helplessness. “Thurber hasn’t the vaguest idea what goes on around here,” he would say.

I became one of the trio about whom he fretted and fussed continually—the others were Andy White and Wolcott Gibbs. His admiration of good executive editors, except in the case of William Shawn, never carried with it the deep affection he 40had for productive writers. His warmth was genuine, but always carefully covered over by gruffness or snarl or a semblance of deep disapproval. Once, and only once, he took White and Gibbs and me to lunch at the Algonquin, with all the fret and fuss of a mother hen trying to get her chicks across a main thoroughfare. Later, back at the office, I heard him saying to someone on the phone, “I just came from lunch with three writers who couldn’t have got back to the office alone.”

Our illnesses, or moods, or periods of unproductivity were a constant source of worry to him. He visited me several times when I was in a hospital undergoing a series of eye operations in 1940 and 1941. On one of these visits, just before he left, he came over to the bed and snarled, “Goddam it, Thurber, I worry about you and England.” England was at that time going through the German blitz. As my blindness increased, so did his concern. One noon he stopped at a table in the Algonquin lobby, where I was having a single cocktail with some friends before lunch. That afternoon he told White or Gibbs, “Thurber’s over at the Algonquin lacing ’em in. He’s the only drinking blind man I know.”

He wouldn’t go to the theater the night The Male Animal opened in January, 1940, but he wouldn’t go to bed, either, until he had read the reviews, which fortunately were favorable.

Then he began telephoning around town until, at a quarter of two in the morning, he reached me at Bleeck’s. I went to the phone. The editor of the New Yorker began every phone conversation by announcing “Ross,” a monosyllable into which he was able to pack the sound and sign of all his worries and anxieties. His loud voice seemed to fill the receiver to 41overflowing. “Well, God bless you, Thurber,” he said warmly, and then came the old familiar snarl: “Now, goddam it, maybe you can get something written for the magazine,” and he hung up, but I can still hear him, over the years, loud and snarling, fond and comforting.