9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

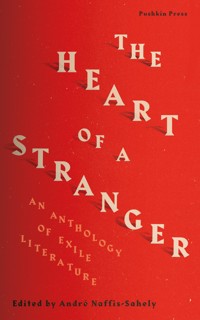

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

A fascinatingly diverse anthology of writing about exile, from the myths of Ancient Egypt to contemporary poetry Exile lies at the root of our earliest stories. From the biblical books of Genesis and Exodus to the Flight of the Irish Earls and Emma Goldman's travails in the wake of the First Red Scare, this fascinatingly diverse selection of writings on exile weaves an intricate and multi-faceted story of expulsions and migrations. The Heart of a Stranger is a miniature history of humanity as seen through the prison of exile, offering a uniquely varied look at a theme both ancient and urgently contemporary. Edited and translated by poet, critic and translator André Naffis-Sahely, this anthology collects poetry, fiction and non-fiction from six continents and over a hundred contributors, to pose urgent questions about the art of literature and the trampling of human rights. Together, the voices in these pages form an energetic polemic about human endurance in the face of displacement, documenting the tyranny of borders and abuses of state power from the ancient world to the present day. André Naffis-Sahely is the author of the collection The Promised Land: Poems from Itinerant Life (Penguin UK, 2017) and the pamphlet The Other Side of Nowhere (Rough Trade Books, 2019). He is from Abu Dhabi, but was born in Venice to an Iranian father and an Italian mother. His translations include over twenty titles of fiction, poetry and nonfiction, featuring works by Honoré de Balzac, Émile Zola, Tahar Ben Jelloun, Rashid Boudjedra, Abdellatif Laâbi and Alessandro Spina. Several of these translations have been featured as 'books of the year' in the Guardian, Financial Times and NPR.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

This anthology is dedicated to Sarah Maguire (1957–2017) poet, translator, friend to exiles

CONTENTS

ORIGINS AND MYTHS

CIVILIZATION BEGETS EXILE; in fact, being banished from one’s home lies at the root of our earliest stories, whether human or divine. As the Abrahamic traditions tell us, if disobeying God was our original sin, then exile was our original punishment. In Genesis, Adam and Eve are expelled from the Garden of Eden after eating the forbidden fruit, their return forever barred by a flaming sword and a host of cherubim. Tragedy of course repeats itself when Cain murders his brother Abel and is exiled east of Eden. Genesis also tells us of the Tower of Babel, an edifice tall enough to reach heaven itself, a monument to human hubris whose destruction scattered its people across the earth and “confounded” our original language, thus making us unintelligible to one another for the first time since creation. The Tanakh, in fact, is rife with exile: Abraham sends Hagar and Ishmael into the wilderness of the Desert of Paran, while the young Moses voluntarily heads into exile after murdering an Egyptian. Genesis and Exodus tell of the captivity of the Israelites in Egypt and their subsequent escape to Sinai, while the Book of Ezra records the end of the Babylonian captivity — the inspiration behind Psalm 137’s immortal lines, “by the rivers of Babylon we sat and wept / when we remembered Zion” — and the eventual return of the Jews to Israel.

Nevertheless, our religious texts tell us that exile wasn’t a fate exclusive to lowly humans. In the Ramayana, the ancient Indian epic, Rama, the Supreme Being of Hinduism, is banished by his father, the Emperor Dasharatha, after falling victim to court intrigues and is ordered to spend fourteen years in exile in the forest of Dandaka, seeking enlightenment amidst demons and wandering holy men. Although Rama is recalled from his exile following his father’s death, he decides to remain in exile for the entire fourteen years. Similarly, in Greek mythology, Hephaestus, the son of Zeus and Hera, is thrown off Mount Olympus by Hera due to his deformities, only to be brought back to Olympus on the back of a mule by the treacherous god of wine, Dionysus. While exile was often a temporary situation for many gods, it was a more permanent state of affairs for their mortal creations.

It was in Babel’s Mesopotamia, towards the end of the Third Dynasty of Ur, that one of our earliest poetic epics, The Lament for Urim, first depicted the vicious cycle of conquest and expulsion that has largely characterized our history. In The Lament for Urim Ningal, the goddess of reeds, pleads before the great gods: “I have been exiled from the city, I can find no rest.” Bemoaning the destruction of her beloved Ur by the invading Elamites, Ningal cries out its name:

O city, your name exists

but you have been destroyed.

O city, your wall rises high

but your Land has perished.

Employing the refrain “woe is me”, Ningal chronicles the annihilation of her world: “I am one whose cows have been scattered”, “My small birds and fowl have flown away”, “My young men mourn in a desert they do not know”. The Sumerian epic ends with a soft, sanguine prayer that Ningal’s city may one day be restored, unleashing one of our first literary archetypes: the hopeful exile. In fact, if The Lament for Urim is any indication, the very concept of recorded history — and literature — appears to spring out of the necessity of exile, preserving in our minds what had been bloodily erased on earth.

The ancient Egyptian “Return of Sinuhe”, written during the Twelfth Dynasty, however, ends on a far happier note. Sinuhe, either a prince or a courtier, depending on the adaptation, flees his native country after an unspecified plot against the throne. Although Sinuhe finds power, wealth and respect in barbaric lands, he cannot quieten the loss that turns all his foreign-won sweetness to ash: “Desire disturbed me, and longing beckoned my heart. There appeared before my eyes scenes of the Nile and the luxuriant greenery and heavenly blue sky and the mighty pyramids and the lofty obelisks, and I feared that death would overtake me while I was in a land other than Egypt.” Fortunately for Sinuhe, his earnest patriotism wins the pharaoh’s mercy when he returns to Egypt as an old man and he is welcomed back into the fold, able to die in his unforgettable homeland. This uncharacteristically happy conclusion to an exile’s suffering shares some similarities with Luke’s “Parable of the Prodigal Son”, where the spendthrift younger son returns home to his father’s undying love — and to the biblical tale of Joseph, who is sold into slavery by his envious brothers, but who then rises to unimaginable heights in Egypt, triggering a series of events that would lead to Moses and the Exodus to the Promised Land, the founding myth of the Israelites. As was written in Exodus 23:9, “thou shalt not oppress a stranger: for ye know the heart of a stranger, seeing ye were strangers in the land of Egypt”.

While exile has accompanied our every step, and our earliest stories and religious myths are studded with tales of woe and banishment, much has been lost precisely because of exile’s oblivion-inducing force. The Greek poet Sappho (c.630–c.570 BC) is perhaps our most famous example. While we know she lived on the island of Lesbos, we do not know what caused her to be exiled to Sicily in her earlier life, and only the tiniest fragments of her reputedly voluminous works have survived. Although exile originally appears to have been the outcome of divine retribution, war or intrigue, it wasn’t long before humans began to play god with the concept themselves. Greek literature shows us that exile was the most common form of retribution for murder, and exile therefore shapes the stories of many of Greece’s most famous mythical heroes, like Peleus, Perseus, Bellerophon and Patroclus, all of whom were killers cast out of society until such time as they could be readmitted. As society grew more complex, however, exile came to be seen as far more useful than simply a punishment for murder. Aristotle’s (384–322 BC) Athenian Constitution introduces us to the law of ostracism, whereby the names of powerful men suspected of abusing their political offices were submitted to a public vote. Assembling in the agora, citizens would scratch the name of the intended exile onto shards of broken pottery and the shards would be tallied up. The man with the most pot-shards was subsequently banished. The chosen exile could be sent away permanently or for a period of ten years, at which point they would be welcomed home and their rights duly restored. This practice proved popular enough to spread to the Greek colonies of southern Italy in Magna Graecia. In his Bibliotheca historica, Diodorus Siculus (90–30 BC) mentions the practice of petalism — from the Greek word for leaf — whereby the citizens of Syracuse wrote the names of the intended exiles on the leaves of olive trees instead of pot-shards.

Regardless of the voting method, this was the way democracy’s enemies were dealt with: if a man grew rich enough to make tyranny inevitable, he was simply banished. Aside from recognizing wealth’s inherent tendency to subvert the public interest, the particular wisdom of this law lay in its focus on exiling powerful individuals rather than their poorer, more numerous partisans, who were often allowed to remain in the city even when their leaders were not. Exile thus not only offered an attractive alternative to execution; it simultaneously hindered the widening of existing social rifts. Themistocles (c.524–459 BC) was perhaps the most famous of these ostracized exiles. After building the Athenian fleet into a major force and fighting the Persians at Marathon, Artemisium and Salamis, Themistocles was implicated in a plot involving the Spartan tyrant Pausanias — most accounts claim unfairly so — and he was subsequently forced to end his days serving the very Persians he had once warred against.

Almost needless to say, however, war never lagged far behind human law-making as the chief wellspring of exile. A fragment by Xenophanes of Colophon (c.570–c.475 BC) provides a clear picture of how the dispersion caused by the Greco–Persian Wars fundamentally reshaped Greek society:

When a stranger appears in wintertime,

these are the questions you must ask,

as you lie reclined on soft couches,

eating nuts, drinking wine by the fire:

“What’s your name?”, “Where do you come from?”,

“How old were you when the Persians invaded?”

Orators, dissidents and artists could be banished just as easily as politicians in ancient Greece, and while many of them were able to secure shelter in faraway cities for some time, exile was never a solid guarantee of safety. Determined to extend his mastery over Greece following his victory in the Lamian War, the Macedonian general Antipater hired a number of “exile-hunters” to capture anyone who had once defamed or opposed his power. For these exiles, no island was distant enough, no temple imperviously sacred. One of Antipater’s most infamous hunters was Archias of Thurii, an actor-turned-mercenary whose scalps included some of Greece’s brightest lights, including Hypereides, Himeraeus and Demosthenes — who committed suicide by chewing on a poisonous reed after Archias finally tracked him down.

While Greek ostracism was engineered to protect a city’s democracy, it was a dictator who first codified exile into Roman law. In 80 BC, Sulla’s Leges Corneliae constitutionalized an already established practice: rather than execute convicted criminals, problematic tribunes or ambitious generals, it was deemed easier to expropriate them, thereby enriching the state’s coffers, and to banish them from the city. Indeed, Polybius tells us that a Roman citizen accused of a crime could voluntarily go into exile in order to avoid being sentenced. Although banished from the capital, such a citizen could travel to certain civitates foederatae — allied cities of Rome — where they could enjoy safety and tranquillity, Neapolis (Naples) being a notable example. As Gordon P. Kelly points out in A History of Exile in the Roman Republic (CUP, 2006), refracted through the prism of Roman law, exilium could describe a variety of situations: “traditional voluntary exile, flight from proscription, magisterial relegatio, retirement from Rome for personal reasons, extended military service, and even emigration or travel”. Furthermore, in order to avoid an exile’s premature return, the policy of aquae et ignis interdictio — exclusion from the communal use of fire and water — created a buffer zone between Rome and the exile’s new “home”, making it illegal for anyone to offer said exile a welcome hearth or refreshment within its bounds.

Strictly speaking, however, softer shades of banishment tended to prove the most popular, given that exilium technically meant that a Roman could be stripped of both his wealth and citizenship, while the lesser relegatio ensured said citizen never lost his rights or property. Many of the more famous Roman exiles belonged to the second category. Ovid (43 BC–AD 18), banished to the Black Sea by Augustus, spent much of his time weeping, sighing and penning servile poems which he hoped would restore his good fortunes in the capital, often interrupting his lyricism in mid-flow to remind his readers that he was merely a relegatus. As for Cicero (106–43 BC), his letters clearly indicate he spent the majority of his eighteen-month exile hopping between luxurious villas, cursing the heavens for his undeserved misfortunes. As such, it is to the Stoic Seneca the Younger (54 BC–ADc.39) that we must turn for a pragmatic outlook on Roman exile: “I classify as ‘indifferent’ — that is, neither good nor evil — sickness, pain, poverty, exile, death. None of these things are intrinsically glorious; but nothing can be glorious apart from them. For it is not poverty that we praise, it is the man whom poverty cannot humble or bend. Nor is it exile that we praise, it is the man who withdraws into exile in the spirit in which he would have sent another into exile.”

Such a sober perspective might have helped Gaius Marius (157–86 BC) make sense of his ironic fate, when, after being hounded across Italy by Sulla’s wrath, he was turned away by the Roman garrison at Carthage, the very city he had once helped Rome to conquer. Marius would have undoubtedly identified with Shakespeare’s Coriolanus (Act III, Scene 3):

Let them pronounce the steep Tarpeian death,

Vagabond exile, flaying, pent to linger

But with a grain a day, I would not buy

Their mercy at the price of one fair word.

Once the Republic perished, Rome’s emperors began to favour the practice of deportatio insulae, or deportation to an island. Tiberius, Caligula and Domitian, among others, exiled quite a few of their family members and enemies — not that the two categories were mutually exclusive, especially in Roman society — to the Pontine islands in the Tyrrhenian Sea. This exilic tradition in the Tyrrhenian would last for thousands of years — until the end of Benito Mussolini’s rule in 1943 — and in its final moments the Pontines housed such prisoners as the novelist Cesare Pavese (1908–50) and the politician Altiero Spinelli (1907–86), who wrote his famous pro-European Manifesto while confined to the island of Ventotene.

NAGUIB MAHFOUZ

The Return of Sinuhe

The incredible news spread through every part of Pharaoh’s palace. Every tongue told it, all ears listened eagerly to it, and the stunned gossips repeated it — that a messenger from the land of Amorites had descended upon Egypt. He bore a letter to Pharaoh from Prince Sinuhe, who had vanished without warning all of forty years before — and whose disappearance itself had wreaked havoc in the people’s minds. It was said that the prince pleaded with the king to forgive what had passed, and to permit him to return to his native land. There he would retire in quiet isolation, awaiting the moment of his death in peace and security. No sooner had everyone recalled the hoary tale of the disappearance of Prince Sinuhe, than they would revive the forgotten events and remember their heroes — who were now old and senile, the ravages of age carved harshly upon them.

In that distant time, the queen was but a young princess living in the palace of Pharaoh Amenemhat I — a radiant rose blooming on a towering tree. Her lively body was clothed in the gown of youth and the shawl of beauty. Gentleness illuminated her spirit, her wit blazed, her intelligence gleamed. The two greatest princes of the realm were devoted to her: the then crown prince (and present king) Senwosret I and Prince Sinuhe. The two princes were the most perfect models of strength and youth, courage and wealth, affection and fidelity. Their hearts were filled with love and their souls with loyalty, until each of the two became upset with his companion — to the point of rage and ruthless action. When Pharaoh learnt that their emotional bond to each other and their sense of mutual brotherhood were about to snap, he became very anxious. He summoned the princess and — after a long discussion — he commanded her to remain in her own wing of the palace, and not to leave it.

He also sent for the two princes and said to them, with firmness and candor, “You two are but miserable, accursed victims of your own blind self-abandon in the pursuit of rashness and folly — a laughing stock among your fellow princes and a joke among the masses. The sages have said that a person does not merit the divine term ‘human’ until he is able to govern his lusts and his passions. Have you not behaved like dumb beasts and love-struck idiots? You should know that the princess is still confused between the two of you — and will remain confused until her heart is inspired to make a choice. But I call upon you to renounce your rivalry in an iron-bound agreement that you may not break. Furthermore, you will be satisfied with her decision, whatever it may be, and you will not bear anything towards your brother but fondness and loyalty — both inwardly and outwardly. Now, are you finished with this business?”

His tone did not leave room for hesitation. The two princes bowed their heads in silence, as Pharaoh bid them swear to their pact and shake hands. This they did — then left with the purest of intentions.

It happened during this time that unrest and rebellion broke out among the tribes of Libya. Pharaoh dispatched troops to chastise them, led by Prince Senwosret, the heir apparent, who chose Prince Sinuhe to command a brigade. The army clashed with the Libyans at several places, besetting them until they turned their backs and fled. The two princes displayed the kind of boldness and bravery befitting their characters. They were perhaps about to end their mission when the heir apparent suddenly announced the death of his father, King Amenemhat I. When this grievous news reached Prince Sinuhe, it seemed to have stirred his doubts as to what the new king might intend towards him. Suspicion swept over him and drove him to despair — so he melted away without warning, as though he had been swallowed by the sands of the desert.

Rumours abounded about Sinuhe’s fate. Some said that he had fled to one of the faraway villages. Others held that he had killed himself out of desperation over life and love. The stories about him proliferated for quite a long time. But eventually, the tongues grew tired of them, consigning them to the tombs of oblivion under the rubble of time. Darkness enveloped them for forty years — until at last came that messenger from the land of the Amorites carrying Prince Sinuhe’s letter — awakening the inattentive and reminding the forgetful.

King Senwosret looked at the letter over and over again with disbelieving eyes. He consulted the queen, now in her sixty-fifth year, on the affair. They agreed to send messengers bearing precious gifts to Prince Sinuhe in Amora, inviting him to come to Egypt safely, and with honour.

Pharaoh’s messengers traversed the northern deserts, carrying the royal gifts straight to the land of the Amorites. Then they returned, accompanied by a venerable old man of seventy-five years. Passing the pyramids, his limbs trembled and his eyes were darkened by a cloud of distress. He was in Bedouin attire — a coarse woollen robe with sandals. A sword scabbard girded his waist; a long white beard flowed down over his chest. Almost nothing remained to show that he was an Egyptian raised in the palace of Memphis, except that when the sailors’ song of the Nile reached his ears, his eyes became violently dreamy, his parched lips quivered, his breath beat violently in his breast — and he wept. The messengers knew nothing but that the old man threw himself down on the bank of the river and kissed it with ardour, as though he were kissing the cheek of a sweetheart from whom he had long been parted.

They brought him to the pharaoh’s palace. He came into the presence of King Senwosret I, who was seated before him, and said, “May the Lord bless you, O exalted king, for forgiving me — and for graciously allowing me to return to the sacred soil of Egypt.”

Pharaoh looked at him closely with obvious amazement, and said, his voice rising, “Is that really you? Are you my brother and the companion of my childhood and youth — Prince Sinuhe?”

“Before you, my lord, is what the desert and forty years have done to Prince Sinuhe.”

Shaking his head, the king drew his brother towards him with tenderness and respect, and asked, “What did the Lord do with you during all these forty years?”

The prince pulled himself up straight in his seat and began to tell his tale.

“My lord, the story of my flight began at the hour that you were informed of our mighty father’s death out in the Western Desert. There the Devil blinded me and evil whispers terrified me. So I threw myself into the wind, which blew me across deserts, villages and rivers, until I passed the borders between damnation and madness. But in the land of exile, the name of the person whose face I had fled, and who had dazzled me with his fame, conferred honour upon me. And whenever I confronted trouble, I cast my thoughts back to Pharaoh — and my cares left me. Yet I remained lost in my wanderings, until the leader of the Tonu tribes in Amora learnt of my plight, and invited me to see him.

“He was a magnificent chief who held Egypt and its subjects in all awe and affection. He spoke to me as a man of power, asking me about my homeland. I told him what I knew, while keeping the truth about myself from him. He offered me marriage to one of his daughters, and I accepted — and began to despair that I would ever again see my homeland. After a short time, I — who was raised on Pharaoh’s famous chariots, and grew up in the wars of Libya and Nubia — was able to conquer all of Tonu’s enemies. From them I took prisoners, their women and goods, their weapons and spoils, and their heirs, and my status rose even further. The chief appointed me the head of his armies, making me his expected successor.

“The gravest challenge that I faced was the great thief of the desert, a demonic giant — the very mention of whom frightened the bravest of men. He came to my place seeking to seize my home, my wife and my wealth. The men, women and children all rushed to the square to see this most ferocious example of combat between two opponents. I stood against him amidst the cheers and apprehension, fighting him for a long time. Dodging a mighty blow from his axe, I launched my piercing arrow and it struck him in the neck. Fatally weakened, he fell to the ground, death rattling in his throat. From that day onward, I was the undisputed lord of the badlands.

“Then I succeeded my father-in-law after his death, ruling the tribes by sword, enforcing the traditions of the desert. And the days, seasons and years passed by, one after another. My sons grew into strong men who knew nothing but the wilderness of the place for birth, life, glory and death. Do you not see, my lord, that I suffered in my estrangement from Egypt? That I was tossed back and forth by horrors and anxieties and was afflicted by calamities, although I also enjoyed love and the siring of children, reaping glory and happiness along the way. But old age and weakness finally caught up with me, and I conceded authority to my sons. Then I went home to my tent to await my passing.

“In my isolation, heartaches assailed me and anguish overwhelmed me, as I remembered gorgeous Egypt — the fertile playground of my childhood and youth. Desire disturbed me, and longing beckoned my heart. There appeared before my eyes scenes of the Nile and the luxuriant greenery and heavenly blue sky and the mighty pyramids and the lofty obelisks, and I feared that death would overtake me while I was in a land other than Egypt.

“So I sent a messenger to you, my lord, and my lord chose to pardon me and grant me his hospitality. I do not wish for more than a quiet corner to live out my old age, until Sinuhe’s appointed hour comes round. Then he would be thrown into the embalming tank, and in his sarcophagus, the Book of the Dead — guide to the afterlife — would be laid. The professional women mourners of Egypt would wail over him with their plaintive rhyming cries…”

Pharaoh listened to Sinuhe with excitement and delight. Patting his shoulder gently, he said, “Whatever you want is yours.” Then the king summoned one of his chamberlains, who led the prince into his wing of the palace.

Just before evening, a messenger came, saying that it would please the queen if she could meet with him. Immediately, Sinuhe rose to go to her, his aged heart beating hard. Following the messenger, nervous and distracted, he muttered to himself, “O Lord! Is it possible that I will see her once again? Will she really remember me? Will she remember Sinuhe, the young prince and lover?”

He crossed the threshold of her room like a man walking in his sleep. He reached her throne in seconds. Lifting his eyes up to her, he saw the face of his companion, whose youthful bloom the years had withered. Of her former loveliness, only faint traces remained. Bowing to her in reverence, he kissed the hem of her robe. The queen then spoke to him, without concealing her astonishment: “My God, is this truly our Prince Sinuhe?”

The prince smiled without uttering a word. He had not yet recovered himself when the queen said, “My lord has told me of your conversation. I was impressed by your feats, and the harshness of your struggle, though it took me aback that you had the fortitude to leave your wife and children behind.”

“Mercy upon you, my queen,” Sinuhe replied. “What remains of my life merely lengthens my torture, while the likes of me would find it unbearable to be buried outside of dear Egypt.”

The queen lowered her gaze a moment, then, raising up to him her eyes filled with dreams, she said to him tenderly, “Prince Sinuhe, you have told us your story, but do you know ours? You fled at the time that you learnt of Pharaoh’s death. You suspected that your rival, who had the upper hand, would not spare your life. You took off with the wind and traversed the deserts of Amora. Did you not know how your flight injured yourself and those that you love?”

Confusion showed on Sinuhe’s face, but he did not break his silence. The queen continued, “Yet how could you know that the heir apparent visited me just before your departure at the head of the campaign in Libya. He said to me: ‘Princess, my heart tells me that you have chosen the man that you want. Please answer me truthfully, and I promise you just as truthfully that I will be both content and loyal. I would never break this vow.’”

Her majesty grew quiet. Sinuhe queried her with a sigh, “Were you frank with him, my queen?”

She answered by nodding her head, then her breath grew more agitated. Sinuhe, gasping from the forty-year voyage back to his early manhood, pressed her further. “And what did you tell him?”

“Will it really interest you to know my answer? After a lapse of forty years? And after your children have grown to be chiefs of the tribes of Tonu?”

His exhausted eyes flashed a look of perplexity, then he said with a tremulous voice, “By the Sacred Lord, it matters to me.”

She was staring at his face with pleasure and concern, and she said, smiling, “How strange this is, O Sinuhe! But you shall have what you want. I will not hold back the answer that you should have heard forty years ago. Senwosret questioned me closely, so I told him that I would grant him whatever I had of fondness and friendship. But as for my heart…”

The queen halted for a moment as Sinuhe again looked up, his beard twitching, shock and dismay bursting on his face. Then she resumed, “As for my heart — I am helpless to control it.”

“My lord,” he muttered.

“Yes, that is what I said to Senwosret. He bid me a moving goodbye — and swore that he would remain your brother so long as he breathed.

“But you were hasty, Sinuhe, and ran off with the wind. You strangled our high hopes, and buried our happiness alive. When the news of your vanishing came, I could hardly believe it — I nearly died of grief. Afterwards, I lived in seclusion for many long years. Then, at last, life mocked at my sorrows; the love of it freed me from the malaise of pain and despair. I was content with the king as my husband. This is my story, O Sinuhe.”

She gazed into his face to see him drop his eyes in mourning; his fingers shook with emotion. She continued to regard him with compassion and joy, and asked herself: “Could it be that the agony of our long-ago love still toys with this ancient heart, so close to its demise?”

Translated from Arabic by Raymond Stock

THE TORAH

Exodus 23:9

Also thou shalt not oppress a stranger: for ye know the heart of a stranger, seeing ye were strangers in the land of Egypt.

THE BOOK OF PSALMS

Psalm 137

By the rivers of Babylon we sat and wept

when we remembered Zion.

There on the poplars

we hung our harps,

for there our captors asked us for songs,

our tormentors demanded songs of joy;

they said, “Sing us one of the songs of Zion!”

How can we sing the songs of the Lord

while in a foreign land?

If I forget you, Jerusalem,

may my right hand forget its skill.

May my tongue cling to the roof of my mouth

if I do not remember you,

if I do not consider Jerusalem

my highest joy.

Remember, Lord, what the Edomites did

on the day Jerusalem fell.

“Tear it down,” they cried,

“tear it down to its foundations!”

Daughter Babylon, doomed to destruction,

happy is the one who repays you

according to what you have done to us.

Happy is the one who seizes your infants

and dashes them against the rocks.

HOMER

from The Odyssey

Now at their native realms the Greeks arrived;

All who the wars of ten long years survived;

And ’scaped the perils of the gulfy main.

Ulysses, sole of all the victor train,

An exile from his dear paternal coast,

Deplored his absent queen and empire lost.

Calypso in her caves constrain’d his stay,

With sweet, reluctant, amorous delay;

In vain — for now the circling years disclose

The day predestined to reward his woes.

At length his Ithaca is given by fate,

Where yet new labours his arrival wait;

At length their rage the hostile powers restrain,

All but the ruthless monarch of the main.

But now the god, remote, a heavenly guest,

In Æthiopia graced the genial feast

(A race divided, whom with sloping rays

The rising and descending sun surveys);

There on the world’s extremest verge revered

With hecatombs and prayer in pomp preferr’d,

Distant he lay: while in the bright abodes

Of high Olympus, Jove convened the gods:

The assembly thus the sire supreme address’d,

Ægysthus’ fate revolving in his breast,

Whom young Orestes to the dreary coast

Of Pluto sent, a blood-polluted ghost.

“Perverse mankind! whose wills, created free,

Charge all their woes on absolute degree;

All to the dooming gods their guilt translate,

And follies are miscall’d the crimes of fate.

When to his lust Ægysthus gave the rein,

Did fate, or we, the adulterous act constrain?

Did fate, or we, when great Atrides died,

Urge the bold traitor to the regicide?

Hermes I sent, while yet his soul remain’d

Sincere from royal blood, and faith profaned;

To warn the wretch, that young Orestes, grown

To manly years, should re-assert the throne.

Yet, impotent of mind, and uncontroll’d,

He plunged into the gulf which Heaven foretold.”

Here paused the god; and pensive thus replies

Minerva, graceful with her azure eyes:

“O thou! from whom the whole creation springs,

The source of power on earth derived to kings!

His death was equal to the direful deed;

So may the man of blood be doomed to bleed!

But grief and rage alternate wound my breast

For brave Ulysses, still by fate oppress’d

Amidst an isle, around whose rocky shore

The forests murmur, and the surges roar,

The blameless hero from his wish’d-for home

A goddess guards in her enchanted dome;

(Atlas her sire, to whose far-piercing eye

The wonders of the deep expanded lie;

The eternal columns which on earth he rears

End in the starry vault, and prop the spheres).

By his fair daughter is the chief confined,

Who soothes to dear delight his anxious mind;

Successless all her soft caresses prove,

To banish from his breast his country’s love;

To see the smoke from his loved palace rise,

While the dear isle in distant prospect lies,

With what contentment could he close his eyes!

And will Omnipotence neglect to save

The suffering virtue of the wise and brave?

Must he, whose altars on the Phrygian shore

with frequent rites, and pure, avow’d thy power,

Be doom’d the worst of human ills to prove,

Unbless’d, abandon’d to the wrath of Jove?”

Translated from Greek by Alexander Pope

SAPPHO

Fragment 98B

but for you Kleis I have no

spangled—where would I get it?—

headbinder: yet the Mytilinean[

] [

]to hold

]spangled

these things of the Kleanaktidai

exile

memories terribly leaked away

Translated from Greek by Anne Carson

XENOPHANES

Fragment 22

When a stranger appears in wintertime,

these are the questions you must ask,

as you lie reclined on soft couches,

eating nuts, drinking wine by the fire:

“What’s your name?”, “Where do you come from?”,

“How old were you when the Persians invaded?”

Translated from Greek by André Naffis-Sahely

SENECA THE YOUNGER

from Moral Letters to Lucilius

To enable yourself to meet death, you may expect no encouragement or cheer from those who try to make you believe, by means of their hair-splitting logic, that death is no evil. For I take pleasure, excellent Lucilius, in poking fun at the absurdities of the Greeks, of which, to my continual surprise, I have not yet succeeded in ridding myself. Our master Zeno uses a syllogism like this: “No evil is glorious; but death is glorious; therefore death is no evil.” A cure, Zeno! I have been freed from fear; henceforth I shall not hesitate to bare my neck on the scaffold. Will you not utter sterner words instead of rousing a dying man to laughter? Indeed, Lucilius, I could not easily tell you whether he who thought that he was quenching the fear of death by setting up this syllogism was the more foolish, or he who attempted to refute it, just as if it had anything to do with the matter! For the refuter himself proposed a counter-syllogism, based upon the proposition that we regard death as “indifferent”, one of the things which the Greeks call ἀδιάφορα. “Nothing”, he says, “that is indifferent can be glorious; death is glorious; therefore death is not indifferent.” You comprehend the tricky fallacy which is contained in this syllogism — mere death is, in fact, not glorious; but a brave death is glorious. And when you say, “Nothing that is indifferent is glorious”, I grant you this much, and declare that nothing is glorious except as it deals with indifferent things. I classify as “indifferent” — that is, neither good nor evil — sickness, pain, poverty, exile, death. None of these things are intrinsically glorious; but nothing can be glorious apart from them. For it is not poverty that we praise, it is the man whom poverty cannot humble or bend. Nor is it exile that we praise, it is the man who withdraws into exile in the spirit in which he would have sent another into exile. It is not pain that we praise, it is the man whom pain has not coerced. One praises not death, but the man whose soul death takes away before it can confound it. All these things are in themselves neither honourable nor glorious; but any one of them that virtue has visited and touched is made honourable and glorious by virtue; they merely lie in between, and the decisive question is only whether wickedness or virtue has laid hold upon them. For instance, the death which in Cato’s case is glorious, is in the case of Brutus forthwith base and disgraceful. For this Brutus, condemned to death, was trying to obtain postponement; he withdrew a moment in order to ease himself; when summoned to die and ordered to bare his throat, he exclaimed: “I will bare my throat, if only I may live!” What madness it is to run away, when it is impossible to turn back! “I will bare my throat, if only I may live!” He came very near saying also: “even under Antony!”. This fellow deserved indeed to be consigned to life!

Translated from Latin by Richard Mott Gummere