Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: The Great Composers

- Sprache: Englisch

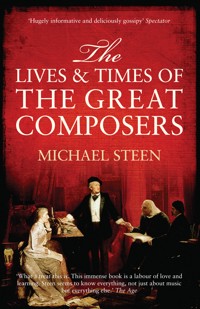

Welcome to The Independent's new ebook series The Great Composers, covering fourteen of the giants of Western classical music. Extracted from Michael Steen's book The Lives and Times of the Great Composers, these concise guides, selected by The Independent's editorial team, explore the lives of composers as diverse as Mozart and Puccini, reaching from Bach to Brahms, set against the social, historical and political forces which affected them, to give a rounded portrait of what it was like to be alive and working as a musician at that time. Indisputably the greatest composer before Mozart, and for many, the greatest composer ever, Johann Sebastian Bach lived out his life in relative obscurity. It may seem incredible to us now, but during his own lifetime he was recognised primarily as an organ virtuoso, rather than a composer of genius. Fewer than a dozen of his compositions were published while he lived and, had not Mendelssohn started the revival of his music in the 19th century, his transcendently beautiful music might easily have been lost to us for ever. At the end of each of his cantata scores, Bach appended the initials SDG: Soli Deo Gloria, to the Glory of God alone. For him 'the aim and final end of all music should be none other than the glory of God and the refreshment of the soul'. Michael Steen follows the profoundly religious Bach through his tough upbringing, to his years of growing fame, replaced by gradual neglect as different fashions overtook his music. Bach's progress as a jobbing musician through the world of small 18th-century German territories was frequently hard and he often found himself out of step with the authorities. Steen explains the background of petty squabbles and the crushing workload against which Bach was to compose polyphony which fused absolute mathematics and absolute poetry; in Wagner's words, 'the most stupendous miracle in all music'.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 74

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published by Icon Books Ltd,

Omnibus Business Centre, 39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP email: [email protected]

ISBN: 978-1-84831-800-7

Text copyright © 2003, 2010 Michael Steen

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael Steen OBE was born in Dublin. He studied at the Royal College of Music, was the organ scholar at Oriel College, Oxford, and has been the chairman of the RCM Society and of the Friends of the V&A Museum, the Treasurer of The Open University, and a trustee of Anvil Arts and of The Gerald Coke Handel Foundation.

Also by the Michael Steen:

The Lives and Times of the Great Composers (ebook and paperback)

Great Operas: A Guide to 25 of the World’s Finest Musical Experiences (ebook and paperback)

Enchantress of Nations: Pauline Viardot, Soprano, Muse and Lover (hardback).

He is currently engaged in a project to publish one hundred ebooks in the series A Short Guide to a Great Opera. Around forty of these have already been published' and further details on these are given at the back of this book.

INTRODUCTION

Welcome to our ebook series The Great Composers, covering fourteen of the giants of Western classical music.

Extracted from his book The Lives and Times of the Great Composers, Michael Steen explores the lives of composers as diverse as Mozart and Puccini, reaching from Bach to Brahms, set against the social, historical and political forces which affected them, to give a rounded portrait of what it was like to be alive and working as a musician at that time.

Indisputably the greatest composer before Mozart, and for many, the greatest composer ever, Johann Sebastian Bach lived out his life in relative obscurity. It may seem incredible to us now, but during his own lifetime he was recognised primarily as an organ virtuoso, rather than a composer of genius. Fewer than a dozen of his compositions were published while he lived and, had not Mendelssohn started the revival of his music in the 19th century, his transcendently beautiful music might easily have been lost to us for ever.

At the end of each of his cantata scores, Bach appended the initials SDG: Soli Deo Gloria, to the Glory of God alone. For him ‘the aim and final end of all music should be none other than the glory of God and the refreshment of the soul’. Michael Steen follows the profoundly religious Bach through his tough upbringing, to his years of growing fame, replaced by gradual neglect as different fashions overtook his music. Bach's progress as a jobbing musician through the world of small 18th-century German territories was frequently hard and he often found himself out of step with the authorities. Steen explains the background of petty squabbles and the crushing workload against which Bach was to compose polyphony which fused absolute mathematics and absolute poetry; in Wagner's words, ‘the most stupendous miracle in all music’.

BACH

A FEW DAYS after Handel was born, less than 100 miles away, Maria Elizabeth Bach gave birth to Johann Sebastian, the latest in a large family and a long line of musicians. Several Bachs had been town musicians in the area, calling the hours, acting as lookouts for troops and for fires. The family was so involved with music that the words ‘musician’ and ‘Bach’ were almost interchangeable.

Eisenach, where Bach was born, is in Thuringia, sandwiched between the forest to the south and the Harz Mountains to the north, in a beautiful yet out-of-the-way part of Saxony, which borders on Hesse. Bach’s father was in charge of music for the town council, responsible for twice-daily performances from the balcony of the town hall and for performing at services in St George’s Church.1

Bach’s background was socially and geographically very different from Handel’s. This goes some way to explaining the difference in their careers, output and subsequent reputation. Bach, ‘parsimonious and prudent’ and with a reputation for being obstinate, immersed himself in narrow-minded Lutheran Saxony.2 Handel, the Italian-trained extrovert, became a risk-taking entrepreneur on an international scale.

Bach is sometimes criticised as ‘an unintelligible musical arithmetician’,3 composing ‘more for the eye than the ear’.4 Indeed, this is how he was often viewed at the end of the 18th century by the small number of people who knew the very few works then in circulation. A century and a half later, Fauré, although an admirer, said that some of his fugues were ‘utterly boring’. 5 Debussy put it more graphically: ‘When the old Saxon Cantor hasn’t any ideas, he starts out from any old thing and is truly pitiless. In fact he’s only bearable when he’s admirable … If he’d had a friend – a publisher perhaps – who could have told him to take a day off every week, perhaps, then we’d have been spared several hundreds of pages in which you have to walk between rows of mercilessly regulated and joyless bars, each one with its rascally little “subject” and “countersubject”.’*8

Often, Bach may give much more pleasure to the performer who will be fascinated by his art, than to the audience disconcerted by his complexity. However, with a little patience, most of his works are totally absorbing and, to some people, he provides almost daily pleasure. Some of his works, the St Matthew Passion being the obvious example, are almost Wonders of the World.

We shall start with Bach’s tough upbringing. After his education, he became organist and choirmaster in two staunchly Protestant towns near his birthplace, first in Arnstadt and then very briefly in Mühlhausen. He then spent nearly ten years working at Weimar, an almost pantomime court. By the time Bach was 30, Handel’s friend Mattheson was talking about ‘der berühmte Bach’, the famous Bach.9 For a short time, he worked in the Frenchified court at Cöthen, away from church music. But church music was his vocation, so he returned to the Lutheran baroque as ‘Cantor’ of St Thomas’ Church in Leipzig. Here, he spent his last three decades, living comfortably, but up a backwater and greatly unappreciated. It is no wonder that he showed signs of having a large chip on his shoulder.

Bach’s achievement was to synthesise laborious German part-writing with the styles of the light French dances and the Italian concertos and sonatas. His works represent a culmination: by the time he was finished, there was musically nothing more anyone could do in his style, except to write exercises and answer examination questions; he had taken it to the limit.10

The music which we have been fortunate to inherit is awesomely beautiful. By the time of his death, however, tastes had changed. For royalty and the aristocrats who led taste and fashion, solid oak furniture had long given way to ormolu, thin veneer and chinoiserie.

BACH’S YOUTH IN THURINGIA AND NORTH GERMANY

Johann Ambrosius Bach, an identical twin, had married the daughter of a furrier and a municipal councillor in Erfurt, where he worked. By the time their son Johann Sebastian was born on 21 March 1685, they had moved to Eisenach, 30 miles away. This part of Germany is steeped in history, particularly Lutheran. Above Eisenach is the Wartburg, the castle where Martin Luther had taken refuge after being declared a heretic at the Diet of Worms. In it, disguised as ‘Junker Georg’ (Squire George), Luther began to translate the New Testament into German; and, as legend has it, he threw an inkpot at the Devil who was attempting to weaken his resolve.11 Long before, in the Middle Ages, there had been a song contest at the Wartburg between the Minnesinger, or poet-musician, ‘Der Tanuser’ and ‘Her Wolveram’, the writer of Parzival; this was immortalised for those who enjoy music by Wagner.12

The Wartburg is so high above Eisenach that one doubts if the young Bach would ever have been allowed to climb up to its ruins. Now restored, the visitor can ponder that here in 1817 was held the first student protest, against the repressive regime of the Habsburg chancellor, Prince Metternich; the visitor can also look at the murals painted by Schubert’s friend Moritz von Schwind; and imagine Franz Liszt conducting the St Elisabeth Oratorio with which he celebrated the Wartburg’s 800th anniversary.

As with all children at the time, Johann Sebastian was lucky to be alive. Half of all babies born in the 17th century died within twelve months of birth. With both disease and war ever present, the average life expectancy was 22 years, with the wealthy and well-fed perhaps living until their early 50s.