Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: The Great Composers

- Sprache: Englisch

Welcome to The Independent's new ebook series The Great Composers, covering fourteen of the giants of Western classical music. Extracted from Michael Steen's book The Lives and Times of the Great Composers, these concise guides, selected by The Independent's editorial team, explore the lives of composers as diverse as Mozart and Puccini, reaching from Bach to Brahms, set against the social, historical and political forces which affected them, to give a rounded portrait of what it was like to be alive and working as a musician at that time. In his short life of not quite 32 years – the briefest span of any first-rank composer – Schubert composed over 600 songs, showing a talent for word-setting which for many has never been equalled. However, while his songs gained gradual fame while he was alive, many of the works for which he is renowned were never performed in his lifetime, not even his Eighth Symphony, the Unfinished, or the Ninth Symphony, The Great C Major, which are so ubiquitous now. He was not lionised for the String Quintet in C, whose second movement Adagio remains one of the most requested pieces on Desert Island Discs. Nor did his exquisite quartets and piano music receive much recognition at the time. Michael Steen evokes Schubert's youth as the son of an impoverished schoolteacher and his life among a boisterous, arty set of friends living it up in the dazzling gaiety of early 19th-century Vienna. Their evening gatherings for an intoxicating mix of politics, conversation and music became known as Schubertiads. At 25 Schubert contracted syphilis and was to suffer ill health for the rest of his life, falling into the depression that is so heart-rendingly expressed in some of his works. Schubert died only a year and a half after Beethoven, having been a torch-bearer at his funeral. Even so, he remained prodigiously productive and those last years bequeathed some of his finest works.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 69

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published by Icon Books Ltd,

Omnibus Business Centre, 39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP email: [email protected]

ISBN: 978-1-84831-803-8

Text copyright © 2003, 2010 Michael Steen

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael Steen OBE was born in Dublin. He studied at the Royal College of Music, was the organ scholar at Oriel College, Oxford, and has been the chairman of the RCM Society and of the Friends of the V&A Museum, the Treasurer of The Open University, and a trustee of Anvil Arts and of The Gerald Coke Handel Foundation.

Also by the Michael Steen:

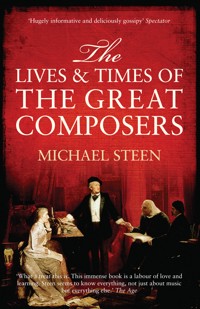

The Lives and Times of the Great Composers (ebook and paperback)

Great Operas: A Guide to 25 of the World’s Finest Musical Experiences (ebook and paperback)

Enchantress of Nations: Pauline Viardot, Soprano, Muse and Lover (hardback).

He is currently engaged in a project to publish one hundred ebooks in the series A Short Guide to a Great Opera. Around forty of these have already been published' and further details on these are given at the back of this book.

INTRODUCTION

Welcome to our ebook series The Great Composers, covering fourteen of the giants of Western classical music.

Extracted from his book The Lives and Times of the Great Composers, Michael Steen explores the lives of composers as diverse as Mozart and Puccini, reaching from Bach to Brahms, set against the social, historical and political forces which affected them, to give a rounded portrait of what it was like to be alive and working as a musician at that time.

In his short life of not quite 32 years – the briefest span of any first-rank composer – Schubert composed over 600 songs, showing a talent for word-setting which for many has never been equalled. However, while his songs gained gradual fame while he was alive, many of the works for which he is renowned were never performed in his lifetime, not even his Eighth Symphony, the Unfinished, or the Ninth Symphony, The Great C Major, which are so ubiquitous now. He was not lionised for the String Quintet in C, whose second movement Adagio remains one of the most requested pieces on Desert Island Discs. Nor did his exquisite quartets and piano music receive much recognition at the time.

Michael Steen evokes Schubert's youth as the son of an impoverished schoolteacher and his life among a boisterous, arty set of friends living it up in the dazzling gaiety of early 19th-century Vienna. Their evening gatherings for an intoxicating mix of politics, conversation and music became known as Schubertiads. At 25 Schubert contracted syphilis and was to suffer ill health for the rest of his life, falling into the depression that is so heart-rendingly expressed in some of his works. Schubert died only a year and a half after Beethoven, having been a torch-bearer at his funeral. Even so, he remained prodigiously productive and those last years bequeathed some of his finest works.

SCHUBERT

‘MUSIC HAS HERE entombed a rich treasure, but much fairer hopes’, was Franz Grillparzer’s epitaph to Schubert.1 The poet was referring to the composer’s premature death, aged only 31. Little did he realise the size of the hoard, which was gradually unearthed through the 19th century. Few had any inkling of how much Schubert had achieved in those few years, composing symphonies, quartets, quintets and masses, and the wonderful piano music.

We shall always associate Schubert with glorious melody, particularly with the Lied, the accompanied German song. Many composers at the time wrote songs.* A ready market for them was provided by the growing middle class, in whose houses there was often a piano to be found, and who considered that an ability to make music was a sign of social advancement. 3 Schubert’s songs are not just ‘settings’ of poems by prominent contemporary poets, such as Goethe and Schiller. Rather, he used each poem to create an entirely new and balanced composition. It is almost as if the poem was the landscape, whereas the song was the landscape painting, the work of art. Leading composers of Lieder, such as Brahms, Hugo Wolf and Richard Strauss, would look back primarily to Schubert for inspiration and as an example to follow.

Even Schubert’s instrumental music is ‘bursting to be sung’.4 The listener emerging from a performance of the Great C major Symphony will have its melodies ringing in his ears. For earlier composers, melody had been mainly a means of providing contrast. For his contemporary Weber, the object of melody was to provide colour. With Schubert, melody, pure lyricism, has become an ‘end in itself ’.5

Schubert’s short life was spent almost wholly in his birthplace, Vienna, although he took occasional summer trips to Hungary or into the Austrian mountains. He was precocious: by the time he turned nineteen, he had already composed his Third Symphony and over 200 songs, including the two for which he used Goethe’s poems ‘Gretchen am Spinnrade’ and ‘Erlkönig’.6 Much of Schubert’s subsequent energy was wasted in a fruitless effort to write an opera, then seen as the crock-of-gold for all composers; he completed seven of them.7 His final years were astonishingly creative. It is all the more incredible that some of his greatest works were produced when suffering from the symptoms of his fatal disease, chronic headaches and giddiness, for example.

Schubert died only around a year and a half after Beethoven, who, stone-deaf, slovenly and sodden in alcohol, had long been out of tune with life in the Habsburg capital. Vienna was a dazzling place, with lots of dancing, several theatres and much gaiety. Schubert himself provided a focus for a small circle of ‘bohemian’ friends whose main interests, music, drink and sex, were not particularly exceptional, other than in extent. The traditional picture of Schubert is, however, of a man who was unassuming and self-effacing. A story is told how, in the salon of Princess Kinsky, the audience applauded the singer but ignored the accompanist. The princess felt she should commiserate; however, Schubert, peering through his spectacles, said that he preferred being unnoticed, ‘for it made him feel less embarrassed’. 8 One friend said: ‘He disliked bowing and scraping, and listening to flattering talk about himself he found down-right nauseating.’9

BIRTHAND YOUTH

Franz Schubert was born on 31 January 1797, in the Himmelpfortgrund, a slum area which the authorities had allowed to develop well back from the walls of central Vienna. The Schuberts lived in Nussdorferstrasse in a building which housed around 70 people in 16 tiny ‘apartments’. From the small courtyard with its pump, a stone staircase leads up to the 25-square-metre tenement. Franz was the twelfth of fourteen children, of whom only four boys and a girl survived into childhood. Older than him were Ignaz, who was a hunchback, Ferdinand and Karl; Maria Theresa was born four years later.10

Franz’s uncle had come to Vienna from Moravia to teach at the Carmelite School in Leopoldstadt, which is just behind the Prater amusement park and some distance from the birthplace. As so frequently happened then, he married the widow of his predecessor and became headmaster. The standard fee per child was very modest, but, because the school had a poor reputation when he took over, he sometimes received less than the standard rate.11

Franz’s father joined his brother as his assistant in about 1783 and later had his own school in the Himmelpfortgrund. Franz’s mother, Elizabeth, was in domestic service and her brother was a weaver. Her father had been fortunate to escape to Vienna from Silesia after he had been accused of embezzlement, a crime for which he could easily have been executed.12