Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Muswell Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: A Jensen Thriller

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

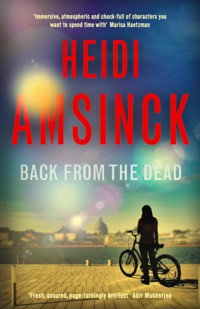

'Immersive, atmospheric and chock-full of characters you want to spend time with. Hope there's more to come' Ambrose Perry. A missing person, a headless corpse, Jensen is on the case.June, and as Copenhagen swelters under record temperatures, a headless corpse surfaces in the murky harbour, landing a new case on the desk of DI Henrik Jungersen, just as his holiday is about to start. Elsewhere in the city, Syrian refugee Aziz Almasi, driver to Esben Nørregaard MP has vanished. Fearing a link to shady contacts from his past. Nørregaard appeals to crime reporter Jensen to investigate. Could the body in the harbour be Aziz? Jensen turns to former lover Henrik for help. As events spiral dangerously out of control, they are thrown together once more in the pursuit of evil, in case more dangerous than they could ever have imagined. Winner of the Danish Crime Academy's Debut Prize for My Name is Jensen

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 423

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ii

iii

v

BACK FROM THE DEAD

Heidi Amsinck

vi

vii

To my brother Henrik

Contents

June

Week One

31

Wednesday 09:37

Detective Inspector Henrik Jungersen squinted through his shades at the divers bobbing up and down in the harbour like seals. Behind him on the quay, by the gleaming spacecraft of the opera house, a crowd of passers-by had gathered with their bicycles, prams and dogs. They were held back by a handful of uniforms but unwavering in their determination to see what was going on. The many police cars suggested it was nothing good.

Henrik had rolled up the sleeves of his white shirt, but still the fabric clung damply to his back. The sun was beating down on his shaved head without mercy. ‘Get on with it,’ he said under his breath as the divers finished placing the body in a bag. He knew this meant the remains were falling apart. This unwelcome thought, along with the smell of diesel and harbour water, was putting him off his takeaway coffee, already lukewarm in his hand.

A couple of officers made a poor job of pulling the bag inside the dinghy. It took a third man to complete the 4mission, the uneven weight distribution threatening for a moment to capsize the vessel.

The dead were heavy.

Especially those with watery graves.

The audience behind him, holding up their phones to film every bit of the action, knew nothing about such things, nor how difficult it was going to be to disentangle the mess that had brought the victim to this sordid end.

Who was he? Not some poor bloke who had drunk one too many in the interval of La Traviata. That much was clear. The fact that his head was missing was a major clue.

The sooner they had the body away to forensics and the crowd dispersed, the better.

Henrik was conscious of the empty space to his left on the cobbled quay. Having dithered for weeks, Detective Sergeant Lisbeth Quist, one of his two trusted wingmen, had finally accepted a move into a bigger job in organised crime courtesy of Henrik’s boss, Superintendent Jens Wiese.

Why had the arsehole done it?

To show he could.

To gain Lisbeth’s eternal gratitude.

To undermine Henrik by picking his team apart.

‘You’ll regret it,’ he had told Lisbeth.

‘My bank balance says I won’t,’ she had replied.

Another rung on the ladder, more money. Henrik got it, yet he was disappointed. Lisbeth still had more to learn, and who better to teach her than himself? Besides, though there were plenty of others to pick from in his team, Henrik couldn’t be arsed to get to know someone new. Someone who would tolerate his foibles without running to the top brass to complain every five minutes. Someone who knew when to talk and when to let him think. Someone he could 5stand pulling an all-nighter with when everything went to shit.

As everything invariably did.

To his right, Detective Sergeant Mark Søndergreen, his one remaining loyal foot soldier, was fidgeting nervously. Though Mark had got on with Lisbeth, Henrik suspected he had at first greeted her departure with relief. With the golden girl out of the way, Mark would finally be able to show what he was made of. But something in the dynamic had changed now that it was just the two of them. Despite Mark’s best efforts at being cheerful, Henrik had felt himself turn sullen and forlorn: like Mikkel, his eldest boy, who barely spoke a word to anyone these days.

‘I wish Lisbeth was here,’ Mark had sighed as they had driven to Holmen in Henrik’s car after the report had come in of a body floating in the harbour.

Henrik knew how unreasonable he was being, but as he stood there on the quay, watching the dinghy with the headless body turn and begin to chug towards them, he felt Lisbeth’s absence as though he too were missing a crucial part of his anatomy.

It was bad enough that Jensen had paired off with another man. Jensen, the woman who didn’t do boyfriends, was now shacked up with the billionaire entrepreneur Kristoffer Bro. She hadn’t spent the night in her Christianshavn flat for ages.

He shouldn’t know that, but he did. He told himself it wasn’t stalking but making sure she was safe.

Kristoffer Bro.

A name he had hoped never to hear again. He had re-read the old police files and they had done nothing to change his view of the man, but Jensen was stubborn. She wouldn’t want to listen. 6

(‘Remind you of anyone?’ said his wife in his head.)

His wife. The mother of his three children, the woman he had spent his entire adult life with, for better or worse. All he had wanted, after she had thrown him out of their Frederiksberg home a few months ago, was for her to forgive him, so everything could go back to normal. At long last, she had relented, and it had felt great.

For about five minutes.

Until he had started to feel the pull of Jensen again.

He loved his wife.

He loved Jensen.

It was fucked up.

Sometimes, he thought of going back to see Isabella Grå, the psychologist with the pretty house in the Potato Rows with whom he had had a few sessions in the spring. ‘Fix me,’ he imagined telling her, throwing himself on her couch. He knew she couldn’t, of course.

He was a lost cause.

‘What have we got?’ he asked the officers in the dinghy as they pulled up to the quay.

‘A deceased male,’ said one of them, looking distinctly green around the gills.

‘I know that. Age? Ethnicity?’

‘Not possible to determine at sight.’

Just then Henrik caught a whiff of putrefied corpse. The water in the harbour was warm this time of year. The body would have discoloured and distorted out of all recognition.

‘But that was probably the point,’ said the officer, speaking without breathing through his nose.

‘Or they wouldn’t have gone to the trouble of cutting the head off?’ said Henrik, spitting away the vomit-heralding saliva that had run into his mouth.

The officer nodded. ‘Or the fingers.’ 7

‘What?’

‘All removed. Someone has gone out of their way to conceal the victim’s identity.’

Henrik sighed. The murder had the hallmarks of a professional job. They weren’t going to be able wrap this one up quickly.

‘And I tell you what,’ the sick-looking officer continued, ‘it must have taken some heft to shift the body into the water, because this guy was built like a brick shithouse.’

82

Wednesday 10:14

Editor-in-chief Margrethe Skov towered above the staff who had assembled in Dagbladet’s canteen, sitting, standing, leaning, some shaking their heads in disgust, others struggling to hide their relief at having avoided the shoulder tap of death.

This time around.

But for how much longer?

Someone had opened the windows wide, succeeding only in admitting the traffic noise of central Copenhagen. If anything, the outside air was making the room hotter. Jensen fanned herself with a copy of yesterday’s paper.

Margrethe was standing tall and broad-shouldered, hands at her waist like an overgrown Peter Pan, her eyes roaming the room behind thick lenses. Where her gaze fell, people looked away. ‘I know this isn’t what any of you were hoping to hear,’ she said. ‘But if we do nothing, we will all be without a job before the year is out. We have a chance to save Dagbladet by acting now. The ten colleagues affected 9have been informed, and I know you’ll all want to join me in thanking them for everything they have done for this important …’ She paused, searching for the appropriate word. ‘… Danish institution.’

There was a commotion at the back of the room, a scraping of chair legs and clogs on lino. Frank Buhl, Dagbladet’s chief crime reporter until this morning was on his feet. ‘You are sleeping with the enemy,’ he shouted, glaring at Margrethe, but jabbing his finger in the direction of the clean-shaven Swede standing behind her.

Hugo Persson, who appeared young enough to be Margrethe’s son, and too young, certainly, to be CEO of a giant venture capital fund, looked horrified at the implication. Someone ought to explain to him the concept of a metaphor, thought Jensen.

Margrethe had briefly introduced Persson at the start. The Swede had made an anaemic speech that no one had listened to, before Margrethe had taken back the reins, determined to be the one breaking the bad news to her staff. She held up her hands in a vain attempt to appease Frank. Her light blue shirt was darkened at the armpits. Beads of sweat were running down her temples.

Jensen lowered her gaze to her own scuffed trainers. No one knew yet that Margrethe had passed Frank’s role on to her, but some of her cannier colleagues would be guessing. Jensen felt their eyes stabbing into her back.

Her phone began to buzz noisily in her hand, startling her. It was Esben Nørregaard, member of parliament in the ruling party, the man who had given her the scoop that had launched her career. And his.

Not now Esben.

She declined the call.

Frank continued, tomato-faced in his lumberjack shirt, 10saggy jeans and braces. ‘How long have we two known each other, Margrethe Skov? And you couldn’t tell me to my face?’ He held up a letter, scrunched it into a ball, threw it on the floor and stamped on it.

His redundancy notice, Jensen assumed.

Did he have a family at home? She vaguely remembered him mentioning a grown-up daughter. At his age, he was unlikely to find another job. She couldn’t see him making the leap to corporate communications somehow, and where else was there to go for newspaper hacks put out to pasture? A freelance bureau, run with diminishing hope from a spare bedroom?

Margrethe had given Jensen an ultimatum: ‘Take the job or leave. Your choice. Either way, Frank is history.’

Jensen knew that the staff cull, the latest of many, was a condition of the Swedish mercy mission. The capital fund had deep pockets and vowed to safeguard the Dagbladet brand, but all the same the Swedes wanted things their way. The future was digital and mobile first, they said. Speculation was rife that they wanted to dispense with the printed edition of the newspaper altogether, though no one could quite bring themselves to believe that Margrethe would agree to that. Meanwhile, Dagbladet was getting a dedicated social media team. Its reporters would be expected to deliver across all platforms. ‘It’s the only way,’ Margrethe had said.

Jensen wasn’t going to argue. Everyone knew Dagbladet was years behind the curve and that its loyal print subscribers across the country were dying off, but why a rich Swedish investment fund would want to back a failing, leftist newspaper in Denmark was perplexing. Rumour had it that Margrethe and the Chairman of the Swedish fund went way back and that she had called in a favour. Jensen hadn’t managed to get at the truth. 11

Yet.

Her phone buzzed again.

Fuck’s sake, Esben, can’t you just wait a minute?

The woman sitting next to her, one of the last photographers left on the newspaper’s payroll, looked at Jensen angrily as though she had spoken out loud. Jensen felt herself blush. This wasn’t the time to attract attention.

‘And now you’re going to let Dagbladet, our Dagbladet, be written by uneducated, unpaid, jumped-up …’

Jensen glanced up and caught Frank’s eye. He faltered, unable or unwilling, despite his anger, to grasp the offensive noun that had been on the tip of his tongue a second ago.

When her phone buzzed again, Jensen felt as if the sound was being pumped out through giant speakers.

Call me now, Jensen, for the love of God!

Getting up, she mumbled an apology and pointed to her phone to show why she had to step away, realising too late that her gesture would only made things worse in the eyes of her colleagues.

She heard tutting behind her. Half-turning, she saw Henning Würtzen, Dagbladet’s ageing obituary writer, slumped on a chair in his beige suit with an unlit cigar in his mouth. He winked at her mischievously.

If the printed edition really was scrapped, how would Henning cope without being able to thumb through the pages, his fingers blackened by newsprint as he chronicled everything that happened to anyone who was anyone in Denmark? Jensen doubted he was even capable of using a laptop or smartphone.

Journalists of Frank Buhl’s generation had learned to 12adapt, but still there was a divide between them and the younger reporters who were digital natives. A decade, maybe two, and that divide would be gone. Would there be anything recognisable left by then of the news industry Jensen had joined as a teenager?

‘Take the job, Jensen. What good would it do if both of you were unemployed?’ Kristoffer had told her that morning as she had agonised over whether to refuse to step into Frank’s shoes on point of principle.

He was right, of course, as Kristoffer often was. In many ways, the two of them were similar people: both loners with few friends, both absorbed in their work and driven to succeed against the odds, neither of them close to their family. ‘I like having you around,’ he had told her. ‘You’re the only person who doesn’t want anything from me.’

She had hesitated before moving in, insisting on keeping the tiny flat in Christianshavn that she had rented from him in the spring. It had been an unnecessary precaution. Kristoffer had turned out to be great company and a good listener, so gradually she had moved most of her stuff into his cavernous waterside penthouse in Nordhavn.

He had humoured her as she had spent hours turning over the case of Carsten Vangede, the Nørrebro bar owner who had (allegedly) committed suicide after passing a USB with information on to her.

In case something happens to me.

Vangede had clearly thought his life was in danger, but the information on the USB had proved impossible to decipher. A bunch of invoices and documents and the address of a mystery property called Amaliekilde in Vedbæk, north of Copenhagen. 13

‘Makes no sense,’ Kristoffer had said. ‘Besides, are your readers really going to care about a paranoid old drunk who thought he had been cheated by his accountant?’

‘But what if his death wasn’t suicide? The pathologist I asked said he couldn’t be a hundred percent sure. What if he was killed because of what he had discovered?’

‘Come on, Jensen. Can’t you hear how far-fetched that sounds?’

She had passed the address of Amaliekilde to Ernst Brøgger, the source she had nicknamed Deep Throat, who had first encouraged her to investigate Vangede’s claims. He had reacted dramatically, telling her to drop the story at once. Brøgger had evaded her calls and emails since, and Jensen had nothing else to go on.

Carsten Vangede had been a bankrupt alcoholic, estranged from his own family. The only evidence of the accountant who had allegedly siphoned money from his bank account was a pair of glasses in a case bearing the name of an optician in Randers, who had refused point blank to talk to Jensen.

What was it Vangede had found and thought important enough to save on a memory stick? Only Brøgger could tell them, Jensen had concluded.

She leaped up the stairs to her office at the top of the newspaper building, relieved to have escaped her role as villain in the canteen horror show.

Gustav, her temporary sidekick, was vaping menthol and staring idly at his phone. ‘Is it over?’ he said, pushing his headphones down and squinting at her through clouds of vapour.

‘Bar the shouting,’ Jensen said. ‘And stop puffing on that bloody thing. I told you, no vaping in here.’

‘Yes ma’am,’ said Gustav. 14

She opened the dormer window as wide as it would go. The office felt like a sauna. The fan she had brought in earlier in the week merely redistributed the hot air, making the papers on her desk flutter like restless birds.

She braced herself for more questions, but Gustav had lost interest. The adult world of payslips, pensions and P45s was never capable of detaining him for long. ‘They’re pulling something from the harbour by the opera house,’ he said, waving his phone at her.

‘What is it?’ said Jensen, frowning.

Gustav shrugged. ‘Dunno. There’s a bunch of people down there. Someone put it on Twitter.’

‘Well, what are you waiting for? Go and check it out.’

Gustav jumped to his feet with a mock private’s solute. His black jeans dropped below his hips, revealing three inches of underpants and one inch of hairless belly.

‘Text me if it’s interesting.’

She listened to his dragging footsteps disappear down the hall before calling Esben back. He answered on the first ring. ‘Jensen, finally. What took you so long?’

‘For God’s sake, Esben, if I don’t answer the phone, it’s because I can’t. I was in the middle of an important meeting.’

‘It’s Aziz,’ said Esben, sounding breathless. ‘He’s missing.’

‘Missing? What do you mean?’

The thought was impossible. The Syrian, who had worked as Esben’s driver since he fled to Denmark in 2015, was at least six foot eight and built like the Hulk. He was as solid a presence on earth as a pile of bricks. People like Aziz didn’t just vanish.

‘He didn’t turn up to get me when I arrived back from Brussels this morning. Never let me down before, so I went to see Amira, his wife. Floods of tears. Transpires Aziz 15hasn’t been seen since shortly after taking me to the airport Monday last week.’

‘That’s, what, nine days ago? Why didn’t she tell you sooner?’

‘Said she didn’t want to disturb me on my trip, but I’m not sure that’s the real reason.’

‘So what is?’

‘Amira is afraid of what would happen to Aziz if they get sent back to Syria, and who can blame her. She doesn’t want to attract any kind of attention to the two of them.’

‘Is that a real possibility? That they’ll be deported?’

‘Not if I’ve got anything to do with it.’

Jensen recalled that Esben was the only politician in the governing party to have spoken out publicly against sending refugees back to Syria. ‘Your stance is well known. Could this be some extreme right-wing thing? Somebody hurting Aziz to get to you?’

‘Could be, but I doubt it. It’s all a while ago now. Got a lot of abuse at the time but it has tapered off now.’

‘So, what do you think has happened to him?’

‘I don’t know. That’s why I’m ringing you.’

‘You should be calling the police.’

‘No.’

‘Why not?’

‘In case Aziz has got himself mixed up in something. I’ve got a bad feeling, Jensen.’

‘I could tell DI Jungersen. He might be able to put a word out on the quiet.’

‘Your cop Romeo, you mean?’ Esben said.

‘He can be trusted, you know.’

‘It baffles me how you can say that after what that bastard has put you through.’

Jensen let it pass. It was a stale repartee. Henrik wasn’t 16good enough for her in Esben’s eyes. ‘My cop Romeo, as you put it, is history. I’m seeing someone else now.’

‘Who?’

‘None of your business,’ she said. ‘What do you want me to do about Aziz?’

‘Meet me in half an hour. Usual place.’

173

Wednesday 11:03

The champagne bar at D’Angleterre was empty except for a couple of waiters polishing glasses and laughing at some private joke. Jensen guessed everyone was outside, desperate for a cooling breeze. They could have done worse than the air-conditioned stone and velvet cave at the back of the luxury hotel.

Esben wasn’t on his usual perch by the bar, the King of Copenhagen with his Savile Row suits, flashing his irresistible smile at all and sundry. She found him in a dark corner, wearing a polo-shirt and creased chinos, nursing a bottle of sparkling water and brooding over his phone.

‘No champagne?’ she said, feeling his forehead. ‘Are you ill, Esben?’

‘Aziz going missing is no joke,’ he said, recoiling from her touch.

The close bond between the Aalborg MP and the Syrian had always puzzled Jensen. Aziz was fiercely defensive of his employer, to the point of hero worship, after Esben had 18given him and his pregnant wife a home when they had first arrived in Denmark, intercepting them as they walked up the motorway towards Sweden.

Understandable.

But she knew less about the source of Esben’s deep affection for Aziz. Whenever she had brought it up in the past, Esben had always changed the subject. She had assumed he was uncomfortable with discussing his role as Aziz’s benefactor, but she could see now that there was more to it. In Aziz, Esben had found someone worthy of a profound respect that he bestowed on few others.

He looked pale under his suntan and had nicked himself shaving, leaving a pearl of congealed blood on his throat. For once, he was showing his age.

‘I’m sorry,’ she said, catching the eye of the waiter and pointing to Esben’s sparkling water. ‘Another one of those, please.’

Esben stared unseeingly at her, frowning as if in great pain. ‘It’s out of character for Aziz to do something like this without at least telling me, let alone his wife.’

‘Going underground, you mean?’

‘If that’s what he’s done, yes.’

‘You think something might have happened to him?’ she said.

Aziz was so strong as to appear invincible, like the marble gods on display at the Ny Carlsberg’s Glyptotek museum. How was it possible that he could have come to harm?

Esben shook his head. ‘I don’t know,’ he said.

Jensen remembered Aziz telling her that he had been a rich man’s driver back home. ‘Could it be related to something that happened to him in Syria? Do you think someone’s after him?’ 19

‘Could be. I really have no idea,’ said Esben, not meeting her eye.

‘But you said that he might have got himself mixed up in something. What did you mean by that?’

‘I just think … it might not be the best idea to involve the police at this stage, before we have an idea of what has happened. Aziz wouldn’t thank us,’ said Esben.

‘There is something else. I can tell,’ said Jensen, her voice hardening.

Esben looked around the bar, misery painted on his face. ‘I didn’t want to tell you over the phone.’

‘What?’

‘I started getting these threatening emails recently.’

‘Who from?’

‘Different Gmail accounts.’

‘Saying?’

‘Die.’

‘That’s it, “Die”?’

‘No, I’m paraphrasing. They threatened to torture, rape and murder my wife, my children, me, in graphic detail.’

‘Esben, that’s horrible. You should go to the police. They can trace the address, find the bastards.’

‘Actually, messages like that have been pretty standard in my time as an MP. Once you step into public life, all the crazies come for you. Might as well mount a target on your back.’

‘All the same, you should have reported it.’

‘I used to. Until I realised that I’d spend half my time running to the cops. No one actually carried out any of the threats, and over time you grow immune.’

Esben fell silent as the waiter brought Jensen’s water and poured it over ice.

‘So, what’s different now?’ she asked after taking a long, thirsty gulp. 20

‘The fact that the emails coincided with Aziz’s disappearance. What if they’d been threatening him, too?’

‘I’m still not hearing a good reason for not going to the police.’ Jensen studied Esben’s face. He avoided her gaze.

‘You think you know who it is, don’t you?’ she said.

‘I can’t prove it, but I think it might be linked to some approaches I’ve had from people wanting me to use my influence with the prime minister to plead their cause. Somewhat ironic, given I’m not exactly her flavour of the month. Well, not after the Syria thing.’

‘All the more reason to report it, though.’

Esben looked at her with a meaningful expression.

Jensen frowned. ‘You’re worried what else they might find?’

‘Well done, Sherlock. And the people in question aren’t the most, shall we say, salubrious. Not the sort you’d want to be seen with in polite company.’

‘Who is it?’

‘I’ll tell you another time. For now, I need you to find Aziz.’

Esben was no angel. A former salesman, he had transformed himself into a politician having been thrust into the public spotlight courtesy of Jensen’s writing. He was certainly not above using his influence or charm with anybody to get what he wanted, including the prime minister, whose trusted inner circle he belonged to, or had done until recently. But one reason why Esben had always resonated so strongly with the electorate was his deep sense of justice. Jensen had only seen him truly angry a handful of times and always because of something he considered blatantly unjust. Shady people and dodgy deals weren’t his style. ‘You always told me the view is better from the moral high ground,’ she said. 21

‘And I still believe that. I’ve never gone along with any of that stuff, but that’s not how some people might see it.’

‘Not good for your image?’

‘Something like that.’

Jensen sighed. ‘What do you want me to do?’

Esben grabbed her hands, looking at her pleadingly. ‘Talk to Amira. Find out what else she knows. Piece together what happened. You’re good at that sort of thing.’

‘Why can’t you talk to her?’

‘I already did, but I can tell she doesn’t trust me.’

‘Can’t blame her for that.’

Amira would have picked up from Aziz or, more likely, concluded by herself that Esben was an incurable womaniser. This was his Achilles’ heel, the one area of his life where his moral compass let him down.

‘I think another woman might help loosen her tongue.’

‘Just anyone with two X chromosomes?’

‘No, Jensen, you. You’re the only one I can trust. Please, will you do this for me? Talk to Amira and find out what’s going on before I lose my mind?’

224

Wednesday 12:22

From Esben’s description Jensen had expected a quivering wreck, but Amira Almasi was composed and calm when she opened the door to the apartment she shared with Aziz and their three children. The tall, slender woman in jeans, pink shirt and a white embroidered headscarf seemed determined not to let her anxiety interfere with her politeness. Only her red-rimmed eyes told of her fear for her husband as she waved Jensen inside. ‘Come in,’ she said in Danish, leading them down a tidy corridor to the lounge where the windows were open with white gauzy curtains dulling the glare of the sun.

The radio was on loud. According to the newsreader it was shaping up to be the hottest June in Denmark on record. On the dining table were books, a notepad with tiny, neat handwriting and a pencil case. ‘I am studying to become a nurse,’ said Amira. ‘Have to use the time when the kids are out of the house, but to be honest I can’t focus on it right now.’ 23

‘That’s understandable,’ said Jensen. ‘How far have you got?’

‘This year’s my first. The summer break has started but I am behind, so I’m trying to catch up. The stupid thing is that I’d almost finished my nursing education in Damascus before we had to leave. Feels as though I’ll never get there.’ She shook her head, then appeared to gather herself. ‘I’m talking too much, sorry. I will get us some tea. Are you hungry?’

‘Always,’ said Jensen, smiling.

The newsreader had moved on to a story about rising inflation and economic misery. Amira switched the radio off. ‘Sorry,’ she said. ‘Only, I listen as much as I can. Helps with my Danish. Esben told me to when Aziz and I first arrived in Denmark.’

‘Seems to have worked a treat,’ said Jensen. While Amira was in the kitchen, she looked around at the couple’s books, photographs and ornaments. There was a large flat-screen TV and a new-looking PlayStation, two controllers neatly stowed side-by-side on the shelf. Jensen imagined Aziz sitting on the sofa between his boys. She felt ashamed that she hadn’t made more of an effort to get to know him. There had been plenty of opportunity back in January when he had chauffeured her around Copenhagen in Esben’s car while she investigated the case of the young man who had been stabbed to death in the snow in Magstræde.

Her phone buzzed in her bag. Probably Gustav, reporting back on the harbour incident. Most likely it had turned out to be nothing. Gustav would be back at Dagbladet by now, bored silly and wondering where she had got to.

Jensen picked up a silver frame with a photo of Amira sitting next to Aziz on a sofa. The couple were cradling an infant, flanked by Esben and his wife Ulla. All four of them were beaming at the camera. 24

‘Esben was good to us. We will never forget it,’ said Amira, who had reappeared carrying a tray with two glasses of fresh mint tea and a plateful of something that was making Jensen salivate.

‘This is Qatayef,’ said Amira. ‘You can find them all over Damascus.’ She offered Jensen the plate of golden half-moons drizzled with syrup and pistachios.

Jensen took a bite of one, feeling the stickiness ooze down her hands. Her mouth filled with sugared nuts. ‘Did you make these?’ she said, licking her fingers.

‘No,’ said Amira. ‘I’m a terrible cook. Aziz made them. I found them in the freezer and heated them in the oven.’ She faltered and looked down at her glass, beginning to cry softly. Her thin shoulders quivered. ‘Sorry,’ she said, lifting a hand to her brow and covering her eyes. She wiped away her tears, got up and disappeared quickly into the bathroom.

Jensen walked up to the door. ‘It’s all right, Amira,’ she said softly. ‘Your husband is missing. No wonder you’re upset.’

‘Just give me a minute,’ Amira said, blowing her nose noisily.

Jensen tiptoed down the hall. There was a bedroom with bunkbeds and toys all over the floor and a box room with a toddler’s cot draped in pink, a four-poster for a princess. The master bedroom was at the end of the hall: tidy, bed made, no clothing in sight. Jensen looked over her shoulder before opening the wardrobe. His clothes to the right, hers to the left. Jensen recognised a jacket Aziz had worn in the winter. The hangers were full. Wherever he had gone, he hadn’t been expecting to stay away for long.

Jensen heard the bathroom tap running and rushed back to the lounge, resuming her seat just in time before Amira rejoined her. 25

‘My husband told me you’re a good journalist: thorough, brave,’ Amira said.

Jensen felt moved that Aziz had talked about her to his wife in such terms, despite the petulance she had shown him when they first met. ‘I try,’ she said. ‘Sometimes I make mistakes.’

Amira waved her hand as if ridding herself of a fly. ‘Esben says I can trust you.’

Jensen nodded. ‘Completely,’ she said. ‘Tell me what happened, Amira, from the beginning. When did you last see Aziz?’

‘Monday morning last week, so nine days ago. He left early to drive Esben to the airport then came back here to take the kids to school. I expected him to return afterwards, but he didn’t.’

‘Did he say anything before he left?’

‘I’ve been racking my brain, but no. He just kissed me goodbye and headed out the door. He seemed happy, untroubled.’

‘And when he didn’t come back, what did you think?’

‘I texted him and asked where he was, then heard his phone ping in the bedroom. I assumed he’d gone to the supermarket, or to see a friend and couldn’t tell me because he’d left his phone behind, so I forgot about it. Until it was time to pick up the kids.’

‘You went yourself?’

‘Yes, but I was annoyed. We had agreed that he would get them, give me some peace to study. But because I hadn’t seen him all day, I couldn’t just leave it to chance, so I headed down to the school. I thought I’d see him there, flustered, apologetic, but to my surprise he hadn’t turned up.’

‘Then what did you do?’ 26

‘I got a neighbour to watch the kids while I went out searching for him.’

‘Where?’

‘His gym. A café he likes. Again nothing.’

‘You must have been getting quite worried by this stage.’

‘Aziz is not the sort of man you worry about. I just thought he had been stupid and inconsiderate. I fully expected to find him creeping into our bed in the middle of the night.’

‘But he didn’t.’

‘No.’

‘Yet, you didn’t report it to the police the next morning. Why not?’

Amira lowered her voice, almost to a whisper. ‘I remembered something he told me. Shortly after we arrived in Denmark. He said there might be people coming for him one day, from Syria, and that he might need to go away for a while if that happened.’

‘You think he has gone into hiding?’

‘Maybe. It’s possible.’

‘Esben tells me you and Aziz have been worrying about being deported?’

Amira became agitated. ‘He can’t go back to Syria, he just can’t.’

‘Why not?’

‘It’s too complicated to explain, but trust me, being sent back to Damascus would be extremely bad for Aziz, for all of us. What I can’t understand is why he has gone without taking anything with him. No clothes, no phone, no passport. There’s been no withdrawals by him on our joint bank account.’

‘You’re concerned something bad might have happened to him after all?’ 27

Amira closed her eyes, nodded, heavy tears plonking onto her folded hands. Jensen reached out and rested her hand on top of hers. ‘We’ll find him,’ she said. ‘I promise you.’

‘The thing is,’ said Amira, sobbing her way through the words. ‘I always thought I would know it … if he was hurt … I would feel it in my heart whether he was dead or alive, but I feel nothing. What do you think that means?’

Jensen squeezed Amira’s hand. ‘Don’t torture yourself,’ she said.

They finished their tea. Jensen had lost the appetite for her pancakes and Amira hadn’t touched hers.

‘You said his phone is here. Could I have it?’ Jensen said. ‘He might have left some clues.’

‘I couldn’t find any, but you’re welcome to it,’ said Amira. ‘The passcode is his mother’s birthday, may God rest her soul. Twenty-fourth of August nineteen-sixty-one. Aziz and I keep no secrets from each other.’

Not necessarily true, given that you don’t know where he is, thought Jensen. While Amira went to get the phone, she pulled her own out of her bag and checked the message she had heard buzzing earlier.

It was Gustav, sure enough.

Body of headless man found in harbour. Margrethe wants the story pronto.

285

Wednesday 12:54

Henrik and David Goldschmidt had exhausted their small talk about the heatwave and climate change, the number one topic of conversation in Copenhagen lately, aside from the ineptitude of the government, which was a constant. David and his husband had recently become vegan and joined Extinction Rebellion, and Henrik had used every means of ribbing the pathologist about his wokeness that he could think of.

‘It’s good to see you back to your normal unreconstructed self,’ David had said, laughing and placing an arm around Henrik’s shoulder.

Am I, back to normal, really? Henrik had thought.

Suited and booted, the two of them were now approaching the stainless-steel table where a pale-green sheet covered lumpy human remains. Henrik was grateful for the cold air in the basement, and for the fact that David couldn’t see the involuntary grimace of disgust that he was making behind his mask. 29

‘I don’t need to tell you that we’re dealing with an extraordinarily large individual, even allowing for the bloating that has occurred in the water,’ said David.

‘Meaning?’

‘Meaning this one would have stood over two metres tall and weighing in at around 120 kilos,’ said David. ‘You ready?’

Henrik blinked in reply, unable to bring himself to say yes or even nod. When was anyone ever ready for being confronted with the putrefied, headless corpse of a fellow man?

Gently, all the while keeping his eyes on Henrik, David peeled back the sheet, exposing a heap of dark flesh. Henrik stood up a little straighter. It wasn’t as bad as he had feared. The corpse had been robbed of its humanity along with its head and fingers.

There was a ragged gash the length of the torso, stretching from the hip to the shoulder, across the sewn-up chest. David saw Henrik looking at it. ‘Sustained after death,’ he said. ‘Probably damaged by something in the harbour.’

‘Tattoos?’ asked Henrik. He couldn’t see any, but the discoloured skin made it hard to tell.

‘None,’ said David. ‘Which is unusual these days.’

‘Cause of death?’

‘Impossible to say without a complete body. No injury to the torso or limbs aside from the gash.’

‘Shot in the head probably,’ said Henrik.

David ignored him, never wanting to be drawn into speculation. ‘Of course, we have to wait for the samples to be analysed, so I can’t say much else. Though there is this.’ He pointed to the man’s wrists. ‘Do you see these lines? Cable ties I reckon.’

Henrik nodded. Rope was fiddly and purchasing 30handcuffs left a trail, whereas cable ties could be picked up for next to nothing from any DIY store. Even the police used them. ‘How were the fingers removed?’ he said.

‘An axe. Same with the head. Quite cleanly. And posthumously.’

‘A professional job, in other words,’ said Henrik.

‘I couldn’t say,’ said David. ‘But I can tell you the body has been in the water for a week or so.’

‘Can you be more precise?’

‘You know I can’t,’ said David, his eyes above the mask smiling.

‘So, we know nothing about the man aside from the fact that he wasn’t shot or stabbed below his head.’

‘Light-skinned. Black body hair. Somewhere between 30 and 40 years of age,’ said David.

‘Doesn’t help much.’ Henrik sighed. ‘Anything noticeable about his clothing?’

‘Levi’s jeans, T-shirt, black leather jacket, Nike trainers,’ said David.

Labels you could buy anywhere in the world. Henrik already knew there had been nothing in the victim’s pockets to indicate his identity. ‘Excellent,’ he said, groaning inwardly at the thought of the case back in January when they had spent more than two weeks trying to identify a stab victim who had turned out to be a Romanian.

‘What’s on your mind?’ said David.

The question hung for a while in the air between them. Henrik knew that the pathologist wasn’t just asking about the case. He had never talked to David about his troubles with his wife and Jensen, but the man had a knack of sensing when Henrik was preoccupied by something personal. He decided not to rise to the bait. ‘I’m thinking that this is something gang-related,’ he said. ‘Warring factions. Once 31we begin unpicking this crime, there will be more nastiness, mark my words.’

He had nothing to base it on, but the sad remains of the man lying on the table gave him a bad vibe. Copenhagen was at peak summer, at first glance transformed into a Mediterranean-style paradise, but as Henrik and his colleagues knew only too well, heatwaves brought spikes in violence. The high temperatures sent people crazy, evil was released all over the city, and now it had been manifested in this luckless corpse recovered from the harbour.

What would be next?

David’s findings had confirmed Henrik’s own sense that the murder had organised crime written all over it. Despite his foreboding, he felt his mood lift fleetingly. At least now he had an excuse to talk to one of three women in his life who had distanced themselves from him lately. And in contrast to Jensen and his wife, Lisbeth Quist might even be pleased to see him.

326

Thursday 09:30

‘Shush,’ shouted Margrethe, dumping her laptop and stack of newspapers on Dagbladet’s elliptical white boardroom table. The faces turning towards her were fewer in number and somewhat younger overall than yesterday when she had announced the latest round of redundancies, but the daily routine was reassuringly the same as always.

For decade after decade, all Dagbladet stories had officially begun and ended at the editorial meeting, and Jensen was glad that Margrethe had no intention of changing this fact. Nor would there be any messing with the newspaper’s provocative political stance; Margrethe had made this abundantly clear to the Swedish venture capitalists. For all her bravado, however, Jensen couldn’t help noticing how drained Margrethe looked. Her thick glasses were opaque with greasy finger marks, her features taut and grim. The negotiations with the Swedes must have taken it out of her, along with the accusations by several press commentators that she had sold out. Few had chosen to look at it from the 33alternative perspective: had it not been for Margrethe and her fighting spirit, Dagbladet would have shut its doors years ago.

Margrethe knew better than anyone that the battle was existential: no money, no newspaper, no validated purveyor of truth and scrutiny of the establishment. They would all regret it when Dagbladet was gone.

Yasmine, Margrethe’s personal assistant, caught Jensen looking and shrugged briefly as if to say, ‘What do you want me to do?’

Yasmine did her best to make sure that her boss was fed, watered and rested, but persuading Margrethe to prioritise her health above reporting on the news was a futile task.

‘No one knows what Yasmine does,’ Jensen had once heard someone say. She suspected that was because Yasmine did everything. Jasmine was Margrethe’s gatekeeper, conscience, eyes and ears and social apologiser. Nothing happened at Dagbladet without Yasmine knowing about it.

In the early days, Jensen had wondered what was in it for the young woman who could have been a high-flying lawyer, but now she recognised that she and Yasmine shared a genuine affection for their boss and her giant brain.

As Margrethe began to run through the day’s stories, Jensen felt Gustav growing restless on the seat next to her. She had just told him about Aziz’s disappearance. He had instantly decided that the headless corpse found in the harbour was that of the Syrian and wouldn’t be persuaded otherwise. Jensen knew he was impatient for the editorial meeting to end, so he could resume his plea. ‘It’s got to be him, Jensen. You must phone the police.’

‘No, not the police, I promised Esben.’

‘Call Henrik then. Jensen, you know who this is.’

Could it be Aziz? It was a possibility, but she didn’t believe it. 34

Not really.

Didn’t want to believe it.

Oh God.

Amira would have seen the news reports and be starting to wonder herself.

‘Earth to Jensen,’ said Margrethe, snapping her fingers. ‘Hallo.’

Jensen looked up to find everyone staring at her. ‘Sorry, what?’

‘I said, decent eyewitness accounts from the recovery of the body in the harbour yesterday.’

‘Thank you,’ said Jensen.

She stopped herself from adding that it was all Gustav’s work. It wasn’t just Frank Buhl who had moaned about the newspaper being written by unpaid teenagers. The staff representative from the Danish Union of Journalists had recently lodged a formal complaint. Margrethe had cut the issue dead by claiming adamantly that Gustav was merely shadowing Jensen to while away the summer months before going back to high school in August, something Margrethe still thought was actually going to happen.

Jensen had her doubts.

In the absence of any information beyond the fact that the body was missing its head, which had swept across Twitter in minutes, Gustav had acted quickly to interview a string of bystanders about what they had seen and how they felt about the macabre find. Nothing but feelings and guesswork, coming from people with no expertise or knowledge of the case whatsoever. Like wheel spin in the sand, but in the twenty-four-hour news cycle, every little piece of content counted.

‘So now what?’ Margrethe said.

‘The police still aren’t talking,’ said Jensen. 35

‘But we think—’ Gustav began, stopping abruptly when she kicked his shin under the table.

‘What Gustav is trying to say is that we tracked down the boat owner who found the body. He has promised Dagbladet an exclusive. We’re seeing him later.’

‘Good,’ said Margrethe. ‘Get him to take you out on the water. Show you how it happened. Film it.’

It was just more filler while they waited for some real news. Jensen knew there was no way around it; she had to call Henrik about Aziz. If for no other reason than to rule out the possibility that she couldn’t bear thinking about.

She had looked briefly through Aziz’s phone without finding anything suspicious. He seemed as square as they came: photos of the family, text exchanges with friends and messages from Esben, including a couple sent last Monday when he had waited in vain for Aziz to collect him from the airport. There were plenty of emails, but they were mostly official or spam. Nothing threatening that Jensen could see.

Perhaps Gustav would have more luck. She sensed him in the corner of her vision, scrolling through Aziz’s WhatsApp messages under the boardroom table.

As the editorial meeting drifted on to other matters, Jensen looked outside the window at the hot sky above the city and felt something coming.

Something bad.

367

Thursday 09:57

The air conditioning in the office had broken down, leaving the incident room roasting and stinking of sweat and frustration after a long night, during which the team of investigators had got precisely nowhere.

‘What’s the point of having air conditioning if it doesn’t bloody work when it’s hot?’ said Henrik, marching over to the windows.

‘None of them open,’ said Mark.

‘Why the hell not?’

‘Interferes with the air conditioning, apparently,’ said Mark, prompting laughter from a couple of the detectives.

Henrik found it difficult to see the funny side. ‘What a dump,’ he said.

‘At least the holidays start soon,’ said Mark, ever the one to spot the silver lining. ‘Should be glorious by the coast if the weather holds.’

‘It won’t,’ said Henrik. ‘Mark my words, the minute you set off for that summer cottage of yours the heavens 37will open. Hello to three weeks of playing Monopoly in the rain.’

‘I like Monopoly,’ said Mark. ‘In any case, that’s not something you need to worry about in Italy, is it?’

‘No,’ said Henrik miserably.

The weather in the Italian coastal resort to which he and his wife had travelled every summer since their first child was born was unfailingly hot and sunny with the odd brief storm to clear the air. It was everything else about the holiday that filled Henrik with angst. He hated flying, a fact he would have ample time to regret, and his wife to moan about, on the long drive down through Germany and across the Alps. And then there was the swimming pool full of screaming kids. The constant bickering and pizza dinners for five that you had to remortgage your house for. No sex, as everyone would be in a family room.

Not that he and his wife were finding it hard to keep their hands off each other these days.

Henrik would happily swap this scenario for a rainy holiday in their log cabin in the north of Zealand.

Watching football and drinking beer.

By himself.

‘Been through missing persons yet?’ asked Henrik.

‘Yes. It helps that our victim was so tall. I quickly narrowed it down to two people.’

‘And?’

‘One is a blond nineteen-year-old, the other a white-haired seventy-four-year-old.’

‘So?’

‘Neither of them fit the profile as we’re looking for a man between thirty and forty with black hair. Also, both are skinny.’ 38

‘Right. And you couldn’t just have said that from the start?’

‘What?’

‘Just … forget it.’

Mark looked perplexed. ‘Shall I check Europol then?’ he said after a moment’s pause.

‘Once we have DNA,’ said Henrik.

‘So, what are we going to do now?’

‘We’re going to speak to Lisbeth. Ask her to meet us in the canteen.’

Mark hesitated. ‘She’s not going to change her mind about the transfer, you know. Don’t you think—’

Henrik closed his eyes. ‘Just. Get. Lisbeth.’