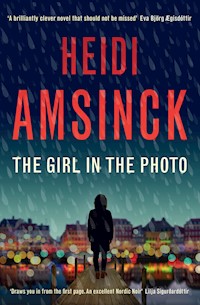

9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Muswell Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Guilty. One word on a beggar's cardboard sign. And now he is dead, stabbed in a wintry Copenhagen street, the second homeless victim in as many weeks. Dagbladet reporter Jensen, stumbling across the body on her way to work, calls her ex lover DI Henrik Jungersen. As, inevitably, old passions are rekindled, so are old regrets, and that is just the start of Jensen's troubles. The front page is an open goal, but nothing feels right…..When a third body turns up, it seems certain that a serial killer is on the loose. But why pick on the homeless? And is the link to an old murder case just a coincidence? With her teenage apprentice Gustav, Jensen soon finds herself putting everything on the line to discover exactly who is guilty.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

MY NAME IS JENSEN

Heidi Amsinck

To Frederik and Jules

Contents

Week One

1

Tuesday 07:13

Jensen sucked the cold air deep into her lungs and let the last few meandering snowflakes melt on her upturned face. Only a few windows were lit in the apartment buildings surrounding her. People on their way to work, their bodies still warm from sleep, were treading gingerly on the pillowy pavements, looking about them as if not recognising their own city. They had forgotten the snow could fall, how it dulled the sounds of their footsteps as though the sky were a lid fitted over Copenhagen. Even the mouthy drunks had vanished from their perch by the supermarket on Christianshavn’s Square, chased indoors by the worst blizzard for many years. In time, the snowploughs would clear the streets, and normality claim the day, but for now the city was holding its frozen breath.

Jensen took her usual route across Knippelsbro to Holmen, past Borgen, the parliament building with its giant verdigris crown, forging a winding track in the snow with her bicycle. She watched the rear of a yellow bus slide out sideways in a wide arc. The windows were steamed up, obscuring the passengers inside, who might be little more than ghosts. Jensen 4 decided she liked the city this silent and deserted, its majestic old buildings taking centre stage. Bar the bus, the scene would have been instantly recognisable to any nineteenth-century Copenhagener.

When she reached Snaregade, it became impossible to cycle any further on the slippery cobbles. She got off and pushed her bike in between the tall, leaning houses of the old town. Just like her to have picked this, of all mornings, to be heading into the newspaper early. Less than twenty minutes ago she had lifted the curtain by her bed to discover the strange bluish-white world outside. It had felt virtuous to get up and head out. Now she wondered if she ought to have stayed put.

Was it possible that she had simply forgotten how to be a journalist? Lost the curiosity and bloody-mindedness that had paid her rent for as long as she could remember?

Since returning to Copenhagen, she had felt enthusiasm seep from her like a slow puncture. To the point where she was no longer able to string a sentence together, let alone a whole article worth reading. Nothing worked, nothing mattered.

She was meant to be Dagbladet’s special reporter, going behind the news with features skewering Danish society. But what did she know about Danish society after fifteen years away?

For weeks she had been promising a feature on cutbacks in mental healthcare, citing delays in gaining document access as an excuse for not turning in copy, but in truth she hadn’t even started researching the story. She supposed it was a crisis of confidence.

Her editor, Margrethe Skov, a woman for whom confidence had never been in short supply, wouldn’t understand. (‘Journalism is a craft, not bloody art; we don’t sit around waiting till we feel inspired.’)

Margrethe was right, of course. Jensen just needed to keep working at it. With a bit of luck, she could have made a solid start on her feature by this morning’s editorial meeting, and 5 how good would that feel, how satisfying to rub the faces of her (by now multiple) detractors in it? Plenty of unemployed journalists would kill to write for Dagbladet, Jensen reminded herself, as she pointed her bike forward, her boots squeaking resolutely in the snow.

She saw it when she was just a few yards into Magstræde.

Against the red building with the green door.

A waist-high mound of snow.

Lumpy.

She looked left and right down the curved street, wishing someone else would turn up, knowing what the lump was, but not wanting to know. For a moment, she considered continuing past it, but how could she?

Her heart was pummelling her rib cage, the sweat beginning to run inside her gloves. Resting her bike against a street lamp, she leaned closer to the lumpy mound, gently brushing away the snow.

She recoiled, stumbling backwards.

It was a man, his face turned towards the sky, his eye sockets filled with snow.

She recognised him. He had been sitting in exactly the same place last night, cross-legged, covered in the same red sleeping bag, though she was pretty sure he had been alive then. She remembered thinking it was an odd place to be asking for money, in the shadows between two street lights with a blizzard underway.

The man’s palms were turned upwards as if he had been professing his innocence or praying when he died, neither of which appeared to have done him much good. He looked a good few years younger than her, perhaps in his early twenties. Hardly more than a boy.

‘Not again,’ she said out loud, only then realising the significance of the words.

Was this really happening? 6

She brushed away more snow, then stopped abruptly when it gave way to raspberry slush. The boy’s puffer jacket was ripped; he had been stabbed in the stomach.

The other victim had been stabbed too, hadn’t he?

On the ground next to the boy was a paper cup full of coffee and a pizza in a cardboard box. There was salami on the pizza; it had curled up and frozen, matching the colour of the dead boy’s skin.

For a moment, Jensen was forced to lean forward with her hands on her knees, as saliva ran out of her mouth and melted a hole in the snow. She retched, her back convulsed, but nothing came.

Her hands were trembling; she shivered, all of a sudden feeling the cold deep inside her bones. How long had the boy been dead for? Hours at most, or someone else would have found him, wouldn’t they? Despite the snow, or even more so because of it, Magstræde was the sort of quaint old street that tourists went mad for. Picture-postcard Copenhagen.

The sky above the tall Lego-coloured town houses was fringed with turquoise now, a fingernail moon fading into the dawn. The snow on the street was pristine except for the tracks she had made.

She looked at her phone, feeling a familiar loosening in her abdomen. She had put off calling Henrik since she had moved back home, ignoring his messages, but he would know what to do about this.

Death was his thing.

He would want to be the first to know.

Besides, calling Henrik would work in her favour. Dagbladet had milked the last murder for all it was worth. In London, homeless deaths might not make the front page, but on the streets of Copenhagen, capital of the happiest nation in the world, it was big news.

Why was the boy there? Who was he? 7

Henrik would be more likely to share information when the time came than a random patrol unit responding to a 112 call.

Henrik owed her.

He owed her so much that no matter what he did for her now, they would never be even.

She caught him in the car going to work, shouting on the hands-free over the din of the radio news. The timbre of his voice darkened when he realised it wasn’t a social call. She heard the siren come on, his car accelerating.

‘Stay where you are,’ he said, in the rough voice he reserved for work. ‘And don’t touch anything.’

Too late for that.

She took a few pictures of the body, though she doubted the paper would be able to use something so graphic. The boy’s open mouth made him look vulnerable, the fluffy hair on his chin not quite enough for a beard. Snowflakes had caught in his eyelashes, turning them white. He was so thin, there were shadowy hollows below his cheekbones.

With her foot, she brushed aside a little of the snow on the ground and saw that he had made a seat for himself out of a flattened cardboard box. His puffer jacket was of a good make, so too his woollen beanie. He had dressed for the weather. She had to keep moving up and down the pavement to stay warm, breathing on her hands. Her exhalations came fast, in little clouds of white steam.

A man walked past. Weirdly, he didn’t give her and the boy a second glance. He had his headphones on and that unseeing gaze of busy city people on their way somewhere important.

That’s how it happens, she thought. That’s how a person dies in the street without anyone noticing.

Magstræde was never exactly busy, though, which made it an odd choice for someone hoping for the charity of passers-by on a night of heavy snow. Perhaps the ban on begging and homeless camps had driven him here? In the dark, half obscured 8 by parked bicycles, he would have been less likely to attract the attention of the police.

She crouched down to look more closely at the dead boy, trying to find the reason for the voice telling her something was wrong, something about his empty hands. Had there not been a sign when she had passed him last night, a piece of cardboard with something scribbled on it? If not, why had she assumed he was a beggar? Of course, she hadn’t actually read it, averting her eyes just like this morning’s commuters. What had it said? Something about being hungry? Whatever it had been, the sign was gone. There was nothing else to see, no personal belongings of any kind, just the pizza and coffee.

She checked her watch.

Her resolve to get to the office early to work on her feature now seemed as much of a lost cause as the dead beggar’s attempts to make a living.

Her eyes were caught by something in the boy’s lap, the corner of a piece of paper protruding from the snow. She put her gloves back on and tugged gently at one corner.

It was a handwritten note:

Fuglereden (the Bird’s Nest), Rysensteensgade

She took a picture of the note before replacing it, then looked up the address on her phone. It was a local hostel. The boy could have had a bed there, hot food, shelter. Yet here he was in front of her, staring up into the sky at something no one else could see.

‘Why didn’t you go there?’ she said out loud, her voice sounding flat in the icy stillness.

As the first sirens approached, she stroked the remaining snow from the boy’s face with her gloved hand and closed his eyes.

2

Tuesday 10:23

‘What are you going to do now?’ Jensen asked Henrik as the paramedics emerged from behind the screen set up by forensics.

Quickly, they put the stretcher with the body into the back of the ambulance, bringing to a halt the entertainment of the people who were craning their necks behind the police tape at the end of the street. Funny that not one of them had been around to help the boy when he was still alive.

Henrik’s unmarked car smelled of his leather jacket; he had turned the engine on to warm them up, and Jensen was slowly regaining the feeling in her fingers. They were both looking at the scene in front of them, but his hand was stroking the inside of her thigh, leaving a trail of electricity in its wake.

She let him.

He had that effect on her.

‘What would you like me to do?’ he said hoarsely.

She knew it would be a disaster to turn and look at him. The brief glimpse she had caught when he had first arrived on the scene, taking charge with his football-player swagger, had been enough. He hadn’t changed in three years. Same black jeans, 10 same white shirt. It must be all there was in his wardrobe, a row of identical shirts and jeans, sleeves rolled up in the summer, down in winter.

Instead of turning her head, she forced herself to stare at a yellow toy tractor by her feet. Henrik bent over, picked up the tractor and tossed it into the back seat. His face was bright red.

‘I meant what are you going to do about the boy?’

They sat in silence for a moment as the ambulance glided away, and the crowd began to disperse.

‘I missed you,’ he said, finally, when everyone but a couple of uniformed officers had left.

He reached further up her thigh. ‘Why didn’t you respond to my messages?’

‘Henrik, you left me in a hotel room.’

‘I had to get back home for my son. Come on, Jensen, you know the score.’

‘You said you’d be five minutes. You said you were going to get a coffee. That was three years ago.’

‘I did try calling.’

‘Six months later. And you wonder why I didn’t pick up?’

She brushed away his hand. Being angry made it a lot easier to look at him.

‘For fuck’s sake, Henrik, two beggars have been murdered on the streets in as many weeks. What are you going to do about it?’

He rubbed his bald head. ‘The two may not be related. Could just be a coincidence.’

‘And if not?’

He withdrew his hand from her thigh, sighing deeply. ‘You heard what forensics said. We have to wait for the post-mortem; it’s too early to tell.’

‘So this is just another day in the office to you?’

‘No, but I have learned never to jump to conclusions, and you would do well to stick to the same advice.’

‘He didn’t look like he was homeless or a typical beggar.’ 11

‘Oh, tell me, what does one of those look like?’

‘His clothes were too clean, too good, for someone who lives on the street.’

‘Why don’t you just come and do my job for me,’ he said, laughing, but she could hear the edge in it.

‘He wasn’t a drunk or some addict,’ she insisted. ‘He had clean clothes, good teeth, good skin. No smell on him, no bottles lying around.’

‘Doesn’t change the fact that we have to wait for the postmortem in order to know what happened to him. Could have been some argument that went wrong.’

‘You don’t know anything about this boy. Young white male, no ID, no phone, no belongings, could be anyone.’

‘Probably Romanian, or some other Eastern European. We still get the odd one sleeping rough here, though the begging ban has made a difference.’

‘He had the address of a homeless shelter. Why didn’t he go there?’

‘Maybe he did.’

‘What?’

‘Last night would have been busy; they might not have had room. Or maybe they wouldn’t let him in for some reason or another.’

‘Why not?’

He held up his hands in mock surrender. ‘Don’t ask me.’

‘All right, so as I was saying, you have no idea who he was or what happened.’

Henrik had no reply to that, and she wasn’t going to wait around for another banal guess.

‘Call me when you know something, anything at all,’ she said and climbed out of the car, slamming the door.

He rolled the window down, imploring her to return, but she ignored him. She wanted to get out of there as fast as she could.

He had that effect on her, too. 12

As she headed for her bicycle, a delivery van drove up behind Henrik’s car, unable to pass in the narrow one-way street. The driver made the mistake of tooting his horn. Henrik responded by tearing open his door and marching up to the van, shoving his police badge into the driver’s face with such aggression that the man began reversing all the way back where he had come from.

Jensen couldn’t help smiling.

Henrik really hadn’t changed one bit.

3

Tuesday 11:49

From the corner office of Dagbladet’s editor-in-chief, Copenhagen’s City Hall Square looked like an abstract painting, a damp mess of white pavements, yellow buses, red tail lights and people rushing to get out of the sleety weather. Jensen watched a group of pedestrians waiting patiently at the kerb for the lights to go green, though they could easily have crossed the road between the cars. In London, you never saw this respect for the rules, this reluctance to stand out from the crowd.

‘Sorry, I’m late,’ said Margrethe, barging into the room carrying a leather shoulder bag and a takeaway coffee.

She settled her tall, broad-shouldered form into the swivel chair behind her desk with a grunt. ‘Had to go and see the prime minister,’ she said.

‘Oh?’

‘Bloody waste of time, before you ask,’ she said, taking off her steamed-up glasses and wiping them on her jumper.

Jensen was about to open her mouth, grateful for the opportunity to delay the conversation she knew was coming, but 14 Margrethe held up a hand to stop her. ‘Save it,’ she said, putting her glasses back on and reaching for her coffee.

Jensen shrank in her chair. Margrethe was one of the few people whose opinion she respected. It was Margrethe who had plucked her from the local paper as an eighteen-year-old without as much as a school leaver’s certificate and given her a job at Dagbladet. Two years later she had sent Jensen to London as the newspaper’s correspondent. There had been plenty of dissenting voices, but Margrethe had ignored them all.

She was taking her time, adding three sachets of sugar to her coffee. The wall behind her was lined with photographs of her all-male predecessors, going back to Dagbladet’s nineteenth-century origins. Compared to Margrethe, with her long grey hair, fleshy face and penetrating gaze behind thick lenses, they looked like a bunch of friendly uncles.

‘I can’t work you out, Jensen,’ said Margrethe, stirring her coffee with a pencil. ‘I fought to keep you when we closed London. They told me not to do it, that you were a pain in the arse, but I ignored them because I always thought you were a great reporter. I sacked someone, an old colleague with five years to retirement, so you could get a job back here. I protected you, took you off the daily beat to give you time for your so-called research, and this is how you repay me?’

She paused, sipping from her cup without taking her eyes off Jensen, who knew better than to interrupt her boss mid-flow.

‘You’ve been back, what, three months? And tell me, how many articles have you written?’

Jensen wriggled her hands under her thighs and looked out of the window at the square below. As she watched, a man standing too close to the kerb got sprayed with dirty slush by a passing taxi.

‘I don’t know exactly. Ten?’ she offered.

‘Four.’

Margrethe rifled through a pile of papers on her desk and 15 pulled out a slim file. ‘Let’s see, ah yes, your reportage on Denmark’s marginal communities.’

‘Took me ages to write.’

‘It’s horseshit. No heart,’ said Margrethe, tossing it to one side.

‘Next, your feature on that dramatic plane crash in Sweden before Christmas.’

‘I received a lot of nice emails afterwards.’

‘Bollocks. I’ve read more engaging articles by sixteen-year-olds on work experience. Want to look at the other two?’

‘No,’ said Jensen.

‘Right, so talk to me. What’s going on?’

‘I need time to settle in.’

Margrethe pretended to consult a printout on her desk. ‘You’ve had three months, and while you’ve got yourself nice and cosy, we’ve lost … let me see … two thousand, eight hundred and seventy subscribers. Any more staff cutbacks, and we may as well switch off the lights.’

Jensen nodded. She had seen the figures. Despite ever-more desperate forays into digital, the 120-year-old newspaper was dying on its feet. Bar a couple of overworked proofreaders, the subs had all gone, and the section editors had to lay out their own pages. The few tired journalists who remained barely had time for more than holding up a microphone to a succession of so-called experts, let alone going digging for stories. You could no longer read Dagbladet confident of finding out what had happened in the world in the previous twenty-four hours, in order of importance. The newspaper was now a personalised ‘experience’ with stories churned out online at regular intervals through the day, clickbait first. Plenty of online readers, but you needed a handful of those to earn as much as you did from one paper subscriber. The traditional business model was irreparably broken, and Dagbladet was yet to find a new one that worked.

‘Give me a chance to—’

16 ‘I have,’ Margrethe snapped. ‘Trust me, if you’d been anyone else, I’d have kicked you out months ago.’

Jensen hung her head.

‘So, whatever is going on with you, fix it.’

‘Yes.’

‘Now leave,’ said Margrethe. ‘I am busy. There’s been another murder. It’s all over Twitter.’

The bells in the tower of City Hall struck twelve noon in the familiar sing-song chime that reminded Jensen of the midday news on the radio in her late grandmother’s kitchen. That was the problem. The bells, Magstræde, City Hall Square, Dagbladet: on the surface they were the same as always, but Copenhagen had changed while she had been away. She felt like a stranger in her own city. Not that she would ever be able to explain that to Margrethe. Her boss had no patience with feeble emotions.

Only one thing impressed Margrethe: a good story.

‘Still here?’ she said, looking irritably at Jensen.

‘Wait. I have something,’ Jensen said, making a swift decision.

‘It better be good.’

‘It was me who found the guy. This morning, in Magstræde.’

‘You did what?’

She told Margrethe everything, leaving only Henrik out of it. Margrethe’s body language softened gradually until she was leaning forward on her elbows, the coffee growing cold by her side.

‘It’s a great story,’ she said when Jensen had finished. ‘“Second homeless man found dead on Copenhagen street. Dagbladet’s reporter discovers the body.”’

‘It might be. I just—’

Margrethe’s voice hardened. ‘I said it’s a great story. This joke of a government has finally gone too far. Now beggars are being killed in the street. Its cruel, heartless, bankrupt policies are bringing shame on the country. Denmark is better than this.’

She waved Jensen off. ‘Write a feature. Eyewitness account, 17 all the trimmings. I’ll get the guys at Borgen to chase down the government for comments. There’s a social campaign in this. The opposition will go mental.’

‘We can’t be sure—’

‘Do it, Jensen!’

Margrethe had already turned towards her desktop and picked up her phone, squeezing it under her chin as she typed. The conversation was over. Jensen headed for the door, already regretting owning up to finding the beggar. But what else did she have?

‘Wait,’ Margrethe shouted after her. ‘Tell me you had the presence of mind to take some pictures before the police arrived?’

Jensen kept her back turned, closing her fist round her mobile phone, cradling the photos she had taken of the dead boy.

‘Sorry,’ she said, squeezing her eyes tightly shut. ‘Must have been the shock. I completely forgot.’

4

Tuesday 12:17

‘Marvellous, just bloody marvellous.’

Chief superintendent Mogens Hansen, known affectionately as ‘Monsen’ (to his intense dislike) was taking his massive corpus for a turn around his desk. From the way he was panting, Henrik guessed it was his first exercise in some considerable time.

It never ceased to amaze him how little work of any kind the head of the investigation unit managed to do. His desk, between two windows that left him backlit and imposing to visitors, was always swept clean of paperwork, and Henrik didn’t remember ever seeing the computer on.

On the wall between the two windows was a portrait of Queen Margrethe II. Henrik remembered it from Monsen’s office at the police yard before they had all been shipped out to the modern building at Teglholmen. Much like its owner, the photo had looked more at home in its previous surroundings.

Henrik resisted the temptation to quip how inconsiderate the Magstræde killer had been to strike just as the government was paying uncomfortably close attention to their department. 19It was Monsen’s hobbyhorse, and if Henrik got him started on it, they would be here for hours.

Monsen kept walking. ‘Two stabbings in ten days, homeless men, a short distance from one another? Hardly a coincidence.’

‘Might be. We don’t know yet.’

‘ID on the first victim?’

‘Not yet.’

‘And this new one?’

‘Same. But our lead theory is that they were Eastern European, possibly Romanian.’

Abruptly, Monsen stopped his round-the desk jaunt, flopped into his chair and made a face like Munch’s The Scream.

‘Find out who did it, Jungersen, and make this stop. At the very least, we must be able to tell if these murders were committed by the same person?’

‘Actually, no. Impossible to say before we have the results of the post-mortem.’

‘So you are telling me we have nothing at all?’

Henrik held up his hands. ‘We’re working as fast as we can.’ He made a move to get up. ‘Talking of which, I’d better …’

Henrik could smell Monsen’s aftershave, the sweat that was just beginning to darken his armpits. The utter misery on the chief super’s face stopped him in his tracks.

‘Fast isn’t fast enough. I just had the commissioner on the phone. Apparently the prime minister wants progress in the next twenty-four hours, she said, or she is going to come over personally and tear me a new arsehole.’

Henrik suppressed a laugh at the thought of the diminutive prime minister administering a spanking to his corpulent boss, though Monsen’s fear was well founded. The police chief represented the old guard of establishment figures whose time had come and gone, in the view of the prime minister. This was the knockout stage. One false move, and Monsen would find himself drawing his pension. 20

Henrik, for one, would regret it if that happened. Monsen’s face might not fit the prime minister’s idea of inclusive leadership, but he was a solid policeman, old school, with no time for the touchy-feely nonsense that had become the bane of Henrik’s life. Besides, deep down, though he would never admit it, Monsen had a soft spot for Henrik, preferring him to Henrik’s immediate boss, Superintendent Jens Wiese, whom both agreed was a boring pen-pusher.

Monsen was almost a whole generation older than him, but Henrik knew that they came from the same mould: working-class lads who could so easily have come down on the wrong side of the law. They had never discussed it (Monsen wasn’t the sort of man you reminisced with at the best of times), but he felt certain that for both of them, joining the force had been about the lure of boy’s-own adventure, cops and robbers, more than any desire to save the world. No one could do that, not even the prime minister, for all her sanctimonious bluster. The world was beyond redemption, full of nasty people motivated by lust and greed, as the likes of Henrik and Monsen knew better than anyone. All you could hope for was containment, and these days perhaps not even that. When it came to the score, the criminals were winning.

Henrik saw all of a sudden how the chief super had aged. Cracks of weakness were beginning to show, and he didn’t like it. It reminded him of his father, his energy all but sucked out of him by life’s million disappointments. Monsen’s most important (if not only) attribute had always been his unwavering self-confidence. Besides, if he was an anachronism, what did that make Henrik?

‘I get it,’ he said. ‘Don’t worry. We’ve got our best team on it. When have I ever let you down?’

Monsen stared at him, incredulous for a moment, as if counting in his mind the thousands of times Henrik had stepped over the line, but they both knew that Henrik was right. In the big 21 scheme of things, which was all that really mattered, he had always come through.

Monsen made a show of looking at his watch. ‘I want you to call me inside midnight with some good news. Is that understood?’

‘Yes, Monsen, of course, Monsen.’

‘Now get back to work.’

Henrik headed for the door, grimacing at the wall in relief.

‘And Jungersen?’

‘Yes?’

‘Call me Monsen one more time and you will be the one with the new arsehole.’

5

Tuesday 13:02

‘Shut up and listen,’ Henrik said, looking around at his team of investigators. Lisbeth Quist and Mark Søndergreen, both decent, plodding detectives more than ten years his junior, had been out all morning and were now perched on the table in the meeting room, still wearing their coats and clutching reusable coffee mugs. He could tell from their downcast faces that they hadn’t had much luck.

Six uniformed officers had crowded in around the door, as though they were expecting some kind of show. They would be sorely disappointed.

‘This morning a member of the public (ha!) discovered the body of an unidentified male in Magstræde,’ he said, pointing to the crime-scene photos fixed to the whiteboard.

‘Preliminary findings suggest that he had been dead four to six hours. Cause of death almost certainly stabbing. No witnesses have come forward.’

He pointed to the second set of crime-scene photos, considerably grislier than the first.

‘We can’t rule out a connection to the murder ten days ago 23 of another, as yet unidentified, male found in Farvergade. Both men appear to have been homeless, both were found without belongings or ID, having sustained multiple stab wounds by a knife not yet recovered. On the other hand, we cannot say for sure that the two murders are linked. The first was a lot more violent than the second.’

He paused, thinking about this. Was it significant? A stabbing was a stabbing, and the two crimes had more circumstances in common than not.

‘Mark, any progress on the first victim?’

‘No. Still no sign of any belongings, and the murder weapon hasn’t been found. We’re looking for witnesses, but so far nothing of use. No CCTV, unfortunately.’

‘Same story in Magstræde,’ said Lisbeth. ‘A few people saw the victim sitting in the street during the day yesterday, but no one witnessed the murder. It would have happened around the time that the blizzard was at its worst.’

‘Excellent,’ said Henrik. ‘So, we’ve no ID, no personal effects, no confirmed cause of death for the second murder, no murder weapon for either, no witnesses and no CCTV. Any questions?’

Mark put his hand up tentatively.

Henrik sighed. ‘What?’

‘Could this be a serial killer? Some far-right nationalist going around taking out foreigners sleeping rough?’

Henrik felt the eyes of the police officers widening.

‘Let’s not start speculating until we have more evidence.’

Meanwhile, the press would be doing all the speculating for them. The headlines he had seen so far would be enough to whip up a frenzy.

‘We do have one lead: a scrap of paper found on the second murder victim with the name and address of the Bird’s Nest, a homeless shelter in Rysensteensgade. I’ll take that one and, Lisbeth and Mark, I want you to go around to the other shelters in the city: find anyone who might have known our two 24 victims or spent time with them in the past few weeks. Take interpreters, if you have to. Then head back to Magstræde and press some more doorbells. One of the residents must have seen or heard something.’

He turned to the police officers.

‘Find the murder weapon or weapons. And look out for wallets or rucksacks or any other personal effects that might have been recovered and handed in to police in the past twenty-four hours. Turn every stone, I don’t want to see you back here with nothing.’

Henrik looked out the window at two female officers striding across the road from the car park and envied their air of purpose. One of them, Henriette, had fancied him once. They had fooled around for a while, until she had got serious, and he had made his excuses. Now she treated him like a leper, something his wife already excelled in. And Jensen, too.

The absence of any personal possessions near the victims was bothering him. Even if you accepted the premise that either victim had possessed anything worth stealing (highly unlikely), you would have expected their empty rucksacks or wallets to have been found nearby. The only other reason he could think of why someone would have taken the stuff would be to delay detection. Unless someone had wanted to hide the identity of the victims, but what would be the point of that? Before long, the police would have all the information they needed.

He looked up to find his colleagues drifting out of the room, chatting among themselves and checking their phones.

‘One more thing,’ he shouted. ‘No one is to discuss this case outside of these four walls, and that includes partners and spouses.’

He knew this was merely a case of delaying the inevitable. Two killings of homeless men in ten days would be irresistible. Little titbits from their investigation would start to find their way into the newspaper columns. Dagbladet would go to town 25 with their coverage, spearheaded by the formidable Margrethe Skov, who would relish giving the government a shoeing for letting people die in the street. He could already see the head-line: Shock discovery by Dagbladet reporter.

It would get him into all sorts of trouble at home when his wife found out. She had been on high alert since she had discovered that Jensen had moved back to Denmark; it would not go down well that she was also now involved in a murder investigation that Henrik was in charge of.

‘Not my thing, crime,’ Jensen had always said. These days he had no idea what her thing was. Not him, it seemed.

Annoying all the same that he couldn’t stop thinking about her. He got out his phone and checked for messages.

Nothing.

6

Tuesday 16:04

With her legs folded at forty-five degrees, there was just enough space for Jensen to perch on the dormer windowsill in her office. She stayed there as dusk fell over the red-tiled roofs of the city and crept into every corner of the room. The sky was the colour of tin, pregnant with more snow.

Most of her colleagues worked on the open-plan floor downstairs, without fixed seats, keeping their laptops and belongings in tiny lockers. She was one of a lucky handful who had their own offices on the unmodernised top floor of the building; yet another reason for her colleagues to hold her in contempt, as if taking someone else’s job and gadding about under Margrethe’s protection (as long as it lasted) wasn’t enough. Though whoever had made the decision to let her have her private space had probably done everyone a favour. Fifteen years of working in London by herself had not exactly honed her skills at rubbing along.

Easy to see now that moving home had been a huge mistake. Margrethe had talked her into it over dinner and copious quantities of wine at an expensive Mayfair restaurant, a rare gesture 27 of generosity intended to soften the blow of her job as Dagbladet’s London correspondent being axed.

‘What good would you be to anyone here – an uneducated Danish hack?’ she had said, half cut and slurring at the end of the evening.

The people at the neighbouring tables had stared, perhaps taking the two of them to be mother and daughter. You would have to be blind to think they had emerged from the same gene pool, but then Margrethe had been acting with unusual familiarity and protectiveness that evening. With the candlelight reflecting in the restaurant’s mirror surfaces, she had painted a picture of opportunity and rediscovery, but in reality, Copenhagen had only made Jensen fonder of London. Back here she felt like a stranger. In London, everyone was. The city was big enough to hide in, to reinvent herself over and over.

After being dismissed from Margrethe’s office, she had spent an unproductive afternoon googling homelessness in Denmark. Rough sleepers were estimated to be in the hundreds in the past year, and a good proportion of the homeless were foreigners. Henrik had been right: the man might not have been able to get a bed for the night anywhere, as hostel facilities had been cut back.

She checked her phone. Henrik hadn’t been in touch. Maybe he had no information yet, maybe he was still smarting from their exchange in Magstræde, but it was not that which had stopped her from writing as much as a single sentence of her article.

Nothing felt right.

She found the photos she had taken on the dead boy. No sign of a struggle or agony in his features. The peaceful look on his face was at odds with the violent injury to his body. And if he had been turned away from the hostel, why had he chosen to stay in Magstræde with his back against a door when there were nooks and crannies nearby offering more shelter and privacy? If he was begging and sleeping rough, how come he was so well 28 dressed? Had he written the address of the shelter on the scrap of paper himself, or had someone given it to him? And how was it even possible to be stabbed in the streets of a big city without anyone discovering it till hours later?

Margrethe was wrong: it wasn’t a great story.

Not yet.

Not that she would tell her boss that to her face. Margrethe had called five times in the past hour alone, chasing for her eyewitness feature, without Jensen having had the nerve to pick up the phone.

She looked up at the familiar sound of shuffling footsteps approaching her office. Henning Würtzen was one of the former editors-in-chief immortalised on the wall in Margrethe’s office, though you would scarcely recognise him from his photograph. Some of the older reporters remembered him retiring in the early 2000s, but no one recalled when he had come back. One day he was just there, shrunken and tortoise-like in his brown suit, with an unlit cigar in his mouth, haunting the corridors of the newspaper like the spectre of journalism past. By default, he had become Dagbladet’s obituary writer. No one of note died without Henning writing about it. He had a vast number of ready obituaries on file, including, rumour had it, his own.

Jensen liked Henning. With no interest in trivial conversations, he was oblivious to the backlash against her return from London as a staff reporter. He walked into her office without knocking, hit the light switch and headed straight for the paper coffee cup on her desk, shaking it to check for remains.

‘Margrethe was asking after you,’ he said, raising the paper cup to his mouth with trembling hands.

‘That’s from yesterday.’

Jensen made a face as Henning drained the cup without any outward sign of disgust.

‘She told me to tell you that Frank is going to write the feature now, and that you should go home and think about how 29 you intend to make a living when you no longer work here,’ he said, looking past her with his rheumy eyes, as if reciting a poem off by heart.

Frank Buhl. Crime writer in clogs. He must have loved being handed such a juicy story, even better seeing as she had shown herself unable to handle it. Well, Frank was welcome to it as far as she was concerned.

‘Was that all?’ she said in a mock-posh voice.

Henning refilled his paper cup and shuffled out of her office, holding up one trembling hand in the affirmative.

No sooner had he left than Jensen heard the sound of clogs approaching.

‘What do you want, Frank?’ she said, staring at the building opposite where an energetic box-fit class was in progress on the floor below.

‘I want you to tell me what you saw. If you can’t be arsed to write it yourself, at least give me something to go on.’

She looked at him. He had a notepad and pen at the ready.

‘I saw a dead man,’ she said.

‘Thanks, that’s brilliant, anything else?’

She made a show of thinking about it.

‘Snow.’

‘Blood?’

‘Yes.’

‘Signs of violence or a struggle?’

‘Not really, except for the blood,’ she said, reminding herself once more of how odd that was.

‘Any belongings or ID lying around?’

She shook her head. ‘No, nothing.’

‘And the doctor attending the scene, what did he conclude?’

‘I am not at liberty to say, I’m afraid.’

That much, at least, was true. Henrik had sworn her to silence, though she wasn’t sure why, seeing as the doctor had only told them what was already obvious to them both. 30

Frank snapped his notebook shut. ‘Well, that’s terrific. You’ve been a great help. Thank you so much. If I can ever return the favour, just let me know. Perhaps …’

‘Perhaps?’

‘Perhaps I can suggest that next time you’re a little less of an arse about it. What the fuck’s wrong with you?’

What was wrong with her? She didn’t know.

When Frank finally left, shaking his head, she climbed down from the windowsill, grabbed her coat and switched off the lights, standing still for a few minutes in the dark office with her eyes closed.

Half a century ago the whole building would have trembled as the presses rolled on the ground floor. The corridor would have been buzzing with the tap-tap of typewriters and reporters rushing in and out of smoke-filled rooms, knowing that what they did mattered, that people all over the country were waiting for the thud of the newspaper landing on their doorstep in the morning. Now the place was dead, a mausoleum to the fourth estate.

She ought not to be surprised. The print media’s decline had begun years before she had even considered becoming a journalist, but somehow working out of her London flat had cushioned her from the worst of it. Here, in the shell of what was once an important institution, there was no escaping the facts.

Her phone pinged. She fished it out of her bag and stood in the dark with her coat on, reading Henrik’s message, her face bathed in the blue light from the screen.

I must see you.

7

Tuesday 18:24

The smell of the flat depressed her: the sweat and exhalations of strangers absorbed by the walls through the years, the meals cooked on the gas rings in the galley kitchen, the odour of mildew from the drains plunging deep below the building. It hit her as soon as she opened the front door, along with the sight of her cardboard boxes piled around the floor. In three months she had failed to unpack, let alone leave any personal mark on the place.

Markus had gone for the Icelandic homestead look, with wooden furniture, candles and sheepskins. It was hopelessly impractical. The sheepskins kept sliding off the chairs, and the table – a slab of wood on trestles – wobbled dangerously under any kind of weight. In one corner, under a red lamp, were the bearded dragons Markus called his ‘girls’. His condition for renting his flat to Jensen while he travelled around the world with his boyfriend was that she fed and watered the girls.

Most of her books, furniture and clothes from London were still in a container in the south Copenhagen harbour, contents for a home of her own as soon as she found one. Hard to do when you weren’t looking. 32

She opened the fridge. There was half a tub of vanilla skyr and two bottles of Carlsberg. She took the skyr and closed the fridge door, then opened it again, put the skyr back and grabbed one of the beers. She drank it sitting on the bed in the dark, listening to the neighbour’s television, a child’s footsteps on the floor upstairs, someone sneezing repeatedly. Across the street there was another apartment building, just like hers, with televisions blaring in dark rooms. When she sat still and held her breath, it was as though she wasn’t there at all.

She opened her laptop. Frank’s piece was online already: Second homeless man found dead in Copenhagen street.

‘Oh, very creative, Frank,’ she said, toasting the screen with her beer.

It was a solid piece, textbook. He had spoken to a handful of ‘experts’ about the shrinking number of hostel beds in Copenhagen and pointed to the obvious question mark now hanging over the controversial begging ban. Her own picture was there, the old mugshot from when she had first started to report from London. It had been during her short-hair phase. She looked like an obstinate boy. Her quote, a declaration of horror at the discovery of the body, was entirely made up (fair enough, she might have done the same in Frank’s place). A spokesperson for the prime minister expressed the government’s concern and promised a full investigation into the case and any failings on the part of social services. This close to a general election, they were willing to promise anything. There were photographs of Magstræde, where people had left flowers and messages, out of guilt, perhaps, for not helping the boy when he had been alive.

She lay back on the faux-fur bedspread and stared at the ceiling, where a leak in the flat upstairs had left a water mark on the plaster. Like the truth, water always found its way through eventually.