Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

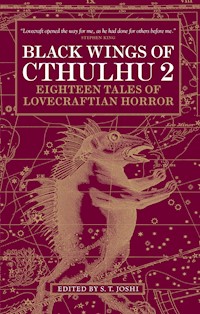

A FEAST OF TERROR In the second volume of the critically acclaimed Black Wings series, S.T. Joshi— the world's foremost Lovecraft scholar—has assembled eighteen more brand-new and imaginative horror tales, inspired by the twentieth century's greatest writer of the supernatural, H. P. Lovecraft. Leading contemporary horror authors, including John Shirley, Tom Fletcher, Caitlín R. Kiernan, Jonathan Thomas, Nick Mamatas, Richard Gavin, Melanie Tem, John Langan, Jason C. Eckhardt, Don Webb, Darrell Schweitzer, Nicholas Royle, Steve Rasnic Tem, Brian Evenson, Rick Dakan, Donald Tyson, Jason V. Brock, and Chet Williamson, will draw upon themes, images, and ideas from the life and work of the master of the genre to deliver a rich feast of terror.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 526

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Also by S. T. Joshi

Title Page

Copyright

IntroductionS. T. Joshi

When Death Wakes Me to MyselfJohn Shirley

ViewTom Fletcher

HoundwifeCaitlín R. Kiernan

King of Cat SwampJonathan Thomas

Dead MediaNick Mamatas

The AbjectRichard Gavin

DahliasMelanie Tem

BloomJohn Langan

And the Sea Gave Up the DeadJason C. Eckhardt

Casting CallDon Webb

The Clockwork King, the Queen of Glass, and the Man with the Hundred KnivesDarrell Schweitzer

The Other ManNicholas Royle

Waiting at the Crossroads MotelSteve Rasnic Tem

The Wilcox RemainderBrian Evenson

Correlated DiscontentsRick Dakan

The Skinless FaceDonald Tyson

The History of a LetterJason V Brock

AppointedChet Williamson

About the Editor

Coming Soon from Titan Books

Also Available from Titan Books

ALSO EDITED BY S. T. JOSHI:

Black Wings of Cthulhu

The Madness of Cthulhu Anthology, Volume One (October 2014)

The Madness of Cthulhu Anthology, Volume Two (October 2015)

Black Wings of Cthulhu 2

Print edition ISBN: 9780857687845

E-book edition ISBN: 9780857687852

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St, London SE1 0UP

First edition: February 2014

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved by the authors. The rights of each contributor to be identified as Author of their Work have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Copyright © 2012, 2014 by the individual contributors.

Introduction Copyright © 2012, 2014 by S. T. Joshi.

Cover Art Copyright © 2012, 2014 by Jason Van Hollander.

With thanks to PS Publishing.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

What did you think of this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at: [email protected], or write to us at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

WWW.TITANBOOKS.COM

Introduction

S. T. JOSHI

WHAT DEFINES A “LOVECRAFTIAN” STORY? THIS SEEMINGLY simple question is in fact full of ambiguities, perplexities, and paradoxes, for the term could encompass everything from the most slavish of pastiches that seek (usually unsuccessfully) to mimic Lovecraft’s dense and flamboyant prose and mechanically replicate his gods, characters, and places, to tales that allusively draw upon Lovecraft’s core themes and imagery, to parodies ranging from the affectionate (Fritz Leiber’s “To Arkham and the Stars”) to the faintly malicious (Arthur C. Clarke’s “At the Mountains of Murkiness”). My goal in the Black Wings series has been to avoid the first at all costs and to foster the second and, to a lesser degree, the third. The days when August Derleth or Brian Lumley could invent a new god or “forbidden book” and therefore declare themselves as working “in the Lovecraft tradition” are long over. What is now needed is a more searching, penetrating infusion of Lovecraftian elements that can work seamlessly with the author’s own style and outlook.

That being said, it becomes vital for both writers and readers to understand the essence of the Lovecraftian universe, and the literary tools he used to convey his aesthetic and philosophical principles. One of the great triumphs of modern Lovecraft scholarship has been to demonstrate that Lovecraft was an intensely serious writer who, as his letters and essays suggest, continually grappled with the central questions of philosophy and sought to suggest answers to them by means of horror fiction. What is our place in the cosmos? Does a god or gods exist? What is the ultimate fate of the human species? These and other “big” questions are perennially addressed in Lovecraft’s fiction, and in a manner that conveys his “cosmic” sensibility—a sensibility that keenly etches humankind’s transience and fragility in a boundless universe that lacks a guiding purpose or direction. At the same time, Lovecraft’s intense devotion to his native soil made him something of a regionalist who vivified the history and topography of Providence, Rhode Island, and all of New England, establishing a foundation of unassailable reality from which his cosmic speculations could take wing.

How contemporary writers have adapted these and other central ideas and motifs into their own work is well demonstrated by the tales in this volume. Cosmic indifferentism is at the heart of Melanie Tem’s “Dahlias,” which does not require explicit horror, or the supernatural, to convey its effects. The uniquely topographical, even archaeological horror that we find in such a tale as At the Mountains of Madness is powerfully demonstrated in Richard Gavin’s “The Abject” and Donald Tyson’s “The Skinless Face.” Tom Fletcher in some sense draws upon the claustrophobic horror that Lovecraft created in “The Dreams in the Witch House” in his unnerving tale, “View.” Nicholas Royle’s “The Other Man” is a searching and terrifying meditation on the theme of identity, a theme is that found in such of Lovecraft’s tales as “The Outsider” and “The Shadow out of Time.”

Alien incursion is at the heart of many Lovecraft tales, and John Langan (“Bloom”) and Jonathan Thomas (“The King of Cat Swamp”) ring very different but equally engaging changes on this complex theme. Thomas’s story is a clear nod, both in setting and in character, to Lovecraft’s “The Call of Cthulhu,” as are, in a very different manner, Jason C. Eckhardt’s “And the Sea Gave Up the Dead” and Brian Evenson’s “The Wilcox Remainder”; Caitlín R. Kiernan’s “Houndwife” is a tip of the hat to “The Hound,” and Nick Mamatas’s “Dead Media” plays a riff on “The Whisperer in Darkness.” But in all these cases, subtle character development of a sort that Lovecraft generally did not favour raises these tales far above the level of pastiche. A rent in the very fabric of the universe is at the heart of Darrell Schweitzer’s inextricable fusion of fantasy and horror, “The Clockwork King, the Queen of Glass, and the Man with the Hundred Knives,” while Steve Rasnic Tem’s “Waiting at the Crossroads Motel” fuses setting and character in a tale whose cosmic backdrop is thoroughly Lovecraftian.

One of the most interesting developments in recent years—perhaps inspired by the mountains of information on Lovecraft’s daily life and character that have emerged through the publication of his letters—is the degree to which Lovecraft himself has become a character, even an icon, in fiction. In very different ways, John Shirley’s “When Death Wakes Me to Myself” and Rick Dakan’s “Correlated Discontents” draws upon Lovecraft’s own personal idiosyncrasies to convey terror and weirdness. The proliferation of Lovecraft’s work in the media—especially film and television—is at the heart of Don Webb’s “Casting Call” and Chet Williamson’s “Appointed,” tales that skirt the borderland of parody while remaining chillingly terrifying. Jason V Brock takes on Lovecraft’s voluminous letter-writing directly with an epistolary tale that suggests far more than it tells.

The fact that writers of such different stripes have chosen to work, however tangentially, in the Lovecraftian idiom is a testament to the vibrancy and eternal relevance of his central themes and concerns. As he memorably wrote, “We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far.” But it is the very purpose of the writer of fiction to venture, in imagination, beyond that placid island, and very often the result is a harrowing sense of our appalling isolation in the cosmic drift. Lovecraft himself spent a lifetime seeking to probe beyond the limitations of the human senses toward the vast cosmos-at-large, and it is evident that a growing cadre of writers are eager to follow him.

S. T. Joshi

When Death Wakes Me to Myself

JOHN SHIRLEY

John Shirley is the author of numerous novels, collections of stories—including the Bram Stoker Award-winning “Black Butterflies”—and scripts. His screenplays include The Crow. His newest novels are Demons (Del Rey, 2007), Black Glass (Elder Signs Press, 2008), Bleak History (Simon & Schuster, 2009), Bioshock: Rapture (Tor, 2011), and Everything Is Broken (Prime Books, 2011).

SOMEONE’S BROKEN INTO THE HOUSE, DOCTOR.”

Fyodor saw no fear in Leah’s gray eyes. But he’d never seen her afraid, and she’d worked closely with him in psychiatrics for almost eight years—ever since he’d finished his internship. She brushed auburn hair from her pale forehead, adjusted her glasses, and went on, “The window latch is broken in your office—and I think I heard someone moving around down in the basement.”

“Did you call the police?” Fyodor asked, glancing toward the basement door. His mouth felt dry.

They stood in the front hallway of the old house, by the open arch to the waiting room. “I did. I was about to call you, when you walked in.”

They didn’t speak for a long moment, both of them listening for the burglar. Wintry morning light angled through the bay windows of the waiting room, casting intricate shadows from the lace curtains across the braided rug. A dog barked down the street; a foghorn hooted. Just the sounds of Providence, Rhode Island…

Then a peal of happy laughter rippled up through the hardwood floorboards. It cut short so abruptly he wondered if he’d really understood the sound. “That sound like laughter to you?”

“Yes.” She glanced at the window. “The police are in no hurry…”

“You should wait out front, Leah.” He was thinking he should try to see to it that whoever this was, they weren’t setting a fire, vandalizing, doing serious damage to the house. He was negotiating to buy it, planning to expand it into a suite of offices with various health services—especially bad timing for vandalism. It was a big house, built in 1825, most of it not in use at the moment. The ground-floor den was ideal for receiving patients; the front living room had been converted into a waiting room.

Fyodor took a step through the archway, into the hall—and then the basement door burst open. A slender young man stood there, a few paces away, holding a bottle in his hand, toothy grin fading. “Oh! I seem to have lost all track of time. How indiscreet of me,” said the young man, in an accent that sounded Deep South. He wore a neat dark suit with a rather antiquated blazer, thin blue tie, starched white shirt, silver cufflinks, polished black shoes. His fingernails were immaculately manicured, his straight black hair neatly combed back. Fyodor noted all this with a professional detachment, but also a little surprise—he’d expected the burglar to be scruffier, more like the sullen young men he sometimes counseled at Juvenile Detention. The young man’s dark brown eyes met his—the gaze was frank, the smile seemed genuine. Still, the strict neatness might place him in a recognizable spectrum of personality disorders.

“You seem lost,” Fyodor said—gesturing, with his hand at his side, for Leah to go outside. Foolish protective instinct—she was athletic, probably more formidable in a fight than he was. “In fact, young man, you seem to have lost your way right through one of our windows…”

“Ah, yes.” His mouth twitched. “But look what I found for you, Dr. Cheski!” He raised the dusty bottle in his hand. It was an old, unlabeled wine bottle. “I never used to drink. I wanted to take it up, starting with something old and fine. I want a new life. I desire to do things differently. Live! I bet you didn’t know there was any wine down there.”

Fyodor blinked. “Um… in fact…” In fact he didn’t think there was any wine in the basement.

A siren wailed, grew louder—and cut short. Radio voices echoed, heavy boot-steps came up the walk, and the young man, sighing, put the bottle on the floor and walked past Fyodor to open the front door. He waved genially at the policemen.

“Gentlemen,” said the young man, “I believe you are here for me. I’m told that my name is Roman Carl Boxer.”

* * *

CARRYING THE DUSTY WINE BOTTLE, FYODOR DESCENDED the basement steps, wondering if this Roman Carl Boxer could have been a patient, someone he’d consulted on, at some point. The face wasn’t familiar, but perhaps he’d been disheveled and heavily acned before. I’m told that my name is Roman Carl Boxer. Interesting way to put it.

The basement was a box of cracked concrete, smelling of mildew; a little water had leaked into a farther corner. A naked light bulb glowed in the cobwebbed ceiling, bright enough to throw stark shadows from what looked like rodent droppings, off to his left. To the right were his crates of old files, recently stored here—they seemed undisturbed. He saw no wine bottles. He could smell dirt and damp concrete. A few scuffs marked the dust coating the floor.

Fyodor started to turn back—it was not a pleasant place to be—but he decided to look more closely at the files. There was confidential patient information in those crates. If this kid had gotten into them…

He crossed to the files, confirmed they seemed undisturbed—then saw the hole in the floor, in the farther corner. A small shiny crowbar, the price sticker still on it, lay close beside the hole. His view of it had been blocked by the crates.

He crouched by the hole—almost two feet square—and saw that a trapdoor of concrete and wood had been removed to lean against the wall. He could make out a number of dark bottles, down inside it, in wooden slots. Wine bottles.

One slot was empty. The bottle he’d brought with him fit precisely in that slot.

* * *

AWEEK LATER.

“Deal’s done,” Fyodor said, with some excitement, as he came into the waiting room. He took off his damp coat, hanging it up, sniffling, his nose stinging from the cold, wet wind. “I own the building! Me and the bank do, anyway.”

“That’s great!” Leah said, the corners of her eyes crinkling with a prim smile. She was hanging a picture on the waiting room wall. It was a print of a Turner seascape: vague, harmless proto-Impressionism in gold and umber and subtle blues; a choice that suggested sophistication, and soothing to psychiatric patients. Still, some psychiatric patients were capable of feeling threatened by anything.

Leah stepped back from the painting, and nodded.

Fyodor thought it was hanging just slightly crooked, but he knew it would irritate her if he straightened it—though she’d only show the irritation as a faint flicker around her mouth. Surprising how well he’d gotten to know her, and, at the same time, how impersonal their relationship was. A professional distance was appropriate. But it didn’t feel appropriate somehow, with Leah…

“That police detective called,” she said, straightening the painting herself. “Asking if we’re going to come to the arraignment for that burglar.”

“I’m not inclined to press charges.”

“Really? They’ve let him out on bail, you know. He might come back.”

“I don’t want to start my new practice here by prosecuting the first mentally ill person I run into.” He went to the bay windows and looked out at the wet streets, the barren tree limbs of the gnarled, blackened elm in the front yard. Leafless tree limbs always made him think of nerve endings.

“He hasn’t actually been diagnosed…”

“He was confused enough to climb in through a window, ignore everything of value, go down to the basement and dig about.”

“Did you have that wine looked at? The stuff he found downstairs?”

Fyodor nodded. “Hal checked it out. Italian wine, from the early twentieth century, shipped direct from some vineyard—and not improved with age. Gone quite vinegary, he told me.” How had Roman Boxer known the wine was there? It seemed to have been sealed up for decades.

Something else bothered him about the incident, something he couldn’t quite define, a feeling there was something he should recognize about Roman Boxer… just out of reach.

“Oh—you got approval for limited testing of SEQ10. The letter’s on your desk. There are some regulatory hoops but…”

SEQ10. They’d been waiting almost a year. Things were coming together.

He turned to face Leah, feeling a sudden rush of warmth for her. It was good to have her on his team. She was always a bit prim, reserved, her wit dry, her feelings controlled. But sometimes…

“And,” she said a little reluctantly, going to the waiting room desk, “your mom called.”

She passed him the message. “Please call. The psycho Psych Tech is at it again.”

His mother: the fly in the ointment, ranting about the psychiatric technician she imagined was persecuting her in the state hospital. But then she was the reason he’d gotten into psychiatry. Her mania, her fits of amnesia. His own analyst had suggested she was also some of the reason he tended to be rather reserved, wound tight—compensating for his mother’s flamboyance. She was flamboyant on the upswings, almost catatonic on the downswings—prone to amnesia. Firm self-control helped him deal with either extreme. And her intervals of amnesia had prompted his interest in SEQ10.

The doorbell rang, and he went to his office to await the first patient of the day. But his first patient wasn’t the first person to arrive. Instead, Leah ushered in a small middle-aged woman with penciled eyebrows, dark red lipstick, a little too much rouge, her black hair tightly caught up in a bun. She wore a pink slicker, her rose-colored umbrella dripping on the carpet as she said, “I know I shouldn’t come without an appointment, Doctor Cheski…” Her cadences tripped rapidly, her voice chirpy, the movements of her head, as she looked back and forth between Fyodor and Leah, seemed birdlike. “But he was so insistent—my son Roman. He said I had to see him here or not at all, and then he hung up on me. God knows he’s been a lot of trouble to you already. Has he gotten here yet?”

“Here? Today?” Fyodor looked at Leah. She shrugged and shook her head.

“He said he’d be upstairs…”

There was a thump from the ceiling. Squeaking footsteps; brisk pacing, back and forth.

Leah put a hand to her mouth and laughed nervously. Quite uncharacteristic of her. “Oh my gosh, he’s broken into the house again.”

Roman’s mother looked back and forth between them. “Not again! I thought he’d made an appointment! He said he didn’t trust anyone else… He barely knows me, you see…” Her lips trembled.

Leah’s brows knit. “Did you—give him up for adoption?”

Another thump came from above. They all looked at the ceiling. “No-o,” Mrs. Boxer said, slowly. “No, he… claims to not remember growing up with us. With his own family! I show him photographs—he says they’re ‘sort of familiar.’ But he says it’s like it didn’t happen to him. I don’t really understand what he means.” She sighed and went quickly on, “He just keeps wandering around Providence—looking for something… but he won’t say what.”

Fyodor knew he should call the police. But when Leah went to the phone, he said, “Wait, Leah.” Claims to not remember growing up with us. With his own family.

SEQ10 was a hypnotic drug for treating, among other things, hysterical amnesia.

Fyodor looked at Mrs. Boxer. She had some very high-quality jewelry; new pumps, sensible but elegant. A rather showy diamond bulked on her wedding ring. She had money, after all. She could pay for therapy. Insurance wouldn’t cover SEQ10.

Fyodor took a deep breath, and, wiping his clammy palms on his trousers, went up the stairs.

He found Roman in the guest room right over the office. Roman was sitting on the edge of the four-poster bed, nervously turning a glass of wine in both hands, around and around—he’d put the wine in a water tumbler from the upstairs bathroom.

“Brought your own wine this time, I see,” Fyodor said.

“Yes. A California Merlot. Still trying to learn how to drink.” Roman smiled apologetically. He wore the same suit as last time. Neat as a pin. “Strange sensation, alcohol.” After a moment he added, “Sorry about the door. No one was here when I came. I needed to get in.”

Fyodor grunted. He planned to rent the room out as an office, and now this guy was damaging it—the door to the outside stairs stood open, the wood about the lock splintered. There was a large screwdriver on the bedside table.

“Why?” Fyodor asked. “I mean—why the urgency about getting in? Why not make an appointment?”

Roman swirled his wine. “I’m… looking for something here. I just—couldn’t wait. I don’t know why.”

* * *

IT WAS AN EVENING SESSION, AFTER FYODOR WOULD normally have gone home. Roman’s mother had already had the broken door replaced and paid a large advance on the therapy. And Roman was more interesting than most of Fyodor’s patients.

Leaning back on the leather easy chair in Fyodor’s office, Roman seemed bemused. Occasionally, he smoothed the lines of his jacket.

“Your mother gave me some background on you,” Fyodor said. “Maybe you can tell me what seems true or untrue to you.”

He read aloud from his notes.

Roman was twenty-one. An only child, he’d had night terrors until he was nine, with intermittent bedwetting. Father passed on when he was thirteen. They weren’t close. Roman had difficulty keeping friends but was likable, and elderly people loved him. He loved cats, but his mother made him stop adopting them after he accumulated four. One died, and he gave it an elaborate burial ritual. Good student in high school, at first, friends mostly with girls—but no girlfriends. Not terribly interested in sex. Bad last year in high school when some sort of Internet bullying took a more personal form. Reluctant to talk about it. Refused to attend the school. Finished with home schooling, GED. Two years of college, attendance quite patchy. Autodidact for the most part. Tendency to have unusual difficulty with cold weather. No close friends “except in books.”

“All that sound right to you, Roman?” Fyodor asked, getting his laptop into word processing mode.

Roman looked vaguely about him. “Not very flattering, is it? Sounds like someone I knew—but it doesn’t feel like it happened to me personally. Apparently it’s me.”

Fyodor typed in his laptop, Possible dissociation due to unacceptable self-image.

“But since last year—your memories seem like… you?”

“Yes—since last year. All that seems real. I can’t remember anything before that unless somebody reminds me, and then it’s… like remembering an old television episode. Except I can’t really remember those either…”

Roman’s eyes kept wandering to the Victorian fixture hanging from the ceiling. “That fixture’s been here a hundred years.”

“I would have thought it’s older than that, really, as this house was built in the early nineteenth century,” Fyodor said absently, adjusting his laptop to make sure Roman couldn’t see what he was typing.

“No,” Roman said firmly. “Installed early twentieth century. But it was made in the nineteenth.”

Fyodor made a note: Possible grandiosity? Faux expertise syndrome? “Your mother says you feel your name is not Roman. Although she showed you a birth certificate. Do you feel the birth certificate is…”

“Is faked, unreal—part of a conspiracy?” Roman chuckled. “Not at all! What I said was, I feel my name is not Roman. I answer to it for simplicity’s sake. And as for what my name really is—I truly don’t know. Roman Boxer is correct—and incorrect. But don’t waste your time asking why that is, I don’t have an answer for you.”

“And this started when you took a walk on a beach…”

“Yes. Last September. We went to Sandy Point. Myself and… well… Mother. She has a little place at Sandy Point… so I have learned. My real memories start—really, as soon as I arrived on the beach that day. Before that I don’t remember much. She’s prompted a few memories, but…” He cleared his throat. “Well, I was feeling odd from the moment I stepped onto the sand.” He smiled dourly. “Not ‘feeling myself.’ And then—it’ll take some telling…”

“Tell me the story.”

Roman brightened. “Now that I enjoy. I’ve got half a dozen notebooks filled with my stories. But this one is true. Very well: It was a fine Indian Summer afternoon. I was in the mood to be alone… this woman who insists she’s my mother—even then, she often put me in that mood… so I went out to Napatree Point. Big sandy spit of land, you know. The sea looked blue, fluffy clouds scudding in the sky, a real postcard picture. Just me and the gulls. Now, I don’t much care for walks by the beach. Rather dislike looking at the unidentifiable things that wash up there. And the smell of the sea—like the smell of some giant animal. I’d rather go to the library. But I keep hearing people talk about how inspirational the sea is. I keep looking to connect with that Big Something out there. So I was walking on the beach, trying to shake the odd feeling of inner dislocation—I did manage to appreciate the way the light comes through the top of the waves and makes them look like blue glass. I shaded my eyes and gazed way out to sea, trying to see all the way to the horizon—and I got this strange feeling that something was looking back at me from out there.”

Fyodor repressed a smile, and typed, Enjoys dramatization.

“All of a sudden I felt like a giddy little kid. Then I had a strange impulse—it just charged up out of my depths. I felt it go right up my spine and into my head, and I was yelling, ‘Hey out there!’” Roman cupped his hands to either side of his mouth, mimicking it. “‘Hey! I’m here!’ I don’t know, I guess I was just being spontaneous, but I felt truly very impish…”

Fyodor typed: Odd diction, archaic vocabulary at times. It comes and goes. Possibly clinically labile? Showing agitation as he tells the story.

“…and I yelled ‘I’m here, come back!’ and it’s funny how my own voice was echoing in my ears and a response just came into my head from nowhere: They tolled—but from the sunless tides that pour… And I yelled that phrase out loud! I’m not sure why. But I’ll never forget it.”

Auditory hallucination, Fyodor typed. Feelings of compulsion.

Roman squirmed in his chair, licked his lips, went on. “It was a curious little thing to think—like an unfinished line of poetry, right?”

Use of antiquated expressions comes and goes: e.g., curious. Affectation?

“And as soon as I said it I heard gigantic big bells ringing, like the biggest church bells you ever heard—and it sounded like they were coming from under the sea! A little muffled, and watery, but still powerful. It got louder and louder, the sound was so loud, it hurt my head, like I was getting slapped with each clang of the bell, and each time it rang it was as if the sea, the stretch of the sea in front of me, got a little darker, and pretty soon it just went black—the whole sea had turned black…”

Hallucinogenic episodes, possible seizure—drug use?—

“…And no, I don’t use drugs, doctor! I can see you thinking it!” He smiled nervously, straightening his tie. “Never have got into drugs! Oh fine, a few puffs on a bong once or twice—barely felt it.”

Fyodor cleared his throat—strangely congested, it was difficult to speak at first—and asked, “This vision of the sea turning black—did you fall down during it? Lose control of your limbs?”

“No! Well… I didn’t fall.” Roman licked his lips, sitting up straight, animated with excitement. “It was as if I was paralyzed by what I was seeing. The blackness sucking up the ocean was holding me fast, you see. But it was really not so much that the sea was turning black—it was that the sea was gone, and it was replaced by a… a night sky! A dark sky full of stars! I was looking down into the sea, but in some other way I was gazing up into this night sky! My stomach flip-flopped, I can tell you! I saw constellations you never heard of, twinkling in the sea—galaxies in the sea!—and one big yellow star caught my eye. It seemed to grow bigger, and bigger, and it got closer—till it filled up my vision. Then, silhouetted on it, was this black ball… a planet! I rushed closer to it—I could see down into its atmosphere. I saw warped buildings, you could hardly believe they were able to stand up, they seemed so crooked, and cracked domes, and pale things without faces flying over them—and I thought, that is the world called…” He shook his head, lips twisted. “Something like… Yegget? Only not that. I can’t remember the name precisely.” Roman shrugged, spread his hands, and then laughed. “I know how it sounds. Anyway—I was gazing at this planet from above and I heard this… this sizzling sound. Then there was a flash of light—and I was back on the beach. I felt a little dizzy, sat down for awhile, kept trying to remember how I’d gotten to that beach. Could not remember, not then. The memory of what I’d seen in the sea, the black sky—that was vivid. And what was before that? Arriving at the beach. Notions of escaping from some bothersome person.”

“Nothing before then?”

“An image. A place: I was lying in a small bed, in a white room, with this sweet little nurse holding my hand. Remembering it, I had a yearning, a longing for that bed, that nurse—that white room. For the comfort of it. I could almost hear her speak.

“Then, on the beach, I felt this scary buzzing in my pocket! I thought I had a snake in there, and I was clawing at it, and then… something fell out. This shiny, silvery, petite machine fell onto the ground. It was buzzing and shaking in the sand like it was mad. I could see it was some kind of instrument—a device. It seemed strange and familiar, both at the same time, right? So I had to think about how to make it work and I opened it and I heard this tiny voice saying, ‘Roman, Roman are you there?’ It was the… it was my mother.” He stared into the distance. His voice trailed off. “My mother.”

“But you didn’t recognize the thing as a cell phone?”

“After she spoke, I remembered—but it was like something from a science-fiction movie I’d seen. Star Trek. I couldn’t recall buying the thing.”

Fyodor made a few notes and nodded. “And since then—the persistent long-term memory issues, your own name seeming unfamiliar. And you had feelings of restlessness?”

“Restlessness. An inner… goading.” Roman settled back in the chair, staring up at the antique light fixture. “I would have trouble sleeping. I’d go out before dawn for these long rambles… in the old section of Providence—with its mellow, ancient life, the skyline of old roofs, Georgian steeples…”

Archaic affectations cropping up more frequently as patient reminisces.

“You said you felt like you were looking for something—?”

“Correct. And I didn’t know what. Just this feeling of ‘It’s right around the next corner, or maybe around the next one’ and so on. Till one day—I was there! I was standing in front of this house, looking at your sign. It was closed—I took a cab to a Target store, just opening for the day. I bought a little crowbar. Went back to the house—the rest is history. I still don’t know exactly what it is about this house. You just bought the place, right? How’d you find it, doc?”

“Oh, my mother suggested it to me, actually. She was in real estate before she…” Fyodor broke off. Not good to talk about personal matters with a patient. “So—anything else? We’re about out of time.”

“Your mother! She was committed, right?” Roman grinned mischievously. “The inspiration for your career! And you an only child, too, like me—imagine that!”

Fyodor felt a chill. “Uh—exactly how—”

“Don’t get spooked, doc,” Roman chuckled. “It’s the Internet. I googled you! The paper you wrote for the Rhode Island Psychiatric Association—it’s online. Tough childhood with sick mother led you to want to understand mental illness…”

Fyodor kept his expression blank. It annoyed him when a patient tried to turn the tables on him. “Okay. Well. Let’s digest all this.” He saved his notes and closed his laptop.

“No therapeutic advice for me, Doctor Cheski?”

“Yes. Something behavioral. Don’t commit any more burglaries.”

Roman came out with a harsh laugh at that.

* * *

ROMAN BOXER WENT HOME WITH THE WOMAN HE doubted was his mother. Fyodor watched through a window as they got into her shiny black Lincoln.

An unstable young man. Perhaps a dangerous young man—researching his doctor’s background, breaking into his office… twice. He should not be seen here…

Roman refused to be committed. “I won’t take those horrible psychiatric meds. I don’t wish to be a zombie. I’ll just run off, end up back here again. This is the place. It took me a long time, wandering around Providence, to find it. I know, Mom says I never lived here. But I was happy here once. I have to get help right here…”

Roman and his mother were both amenable to the use of SEQ10, to search out the core trauma, since it was something the patient only took on a temporary basis, with the doctor in the room. There were forms to be filled out, approval from the APA.

Fyodor went to his office, feeling restless himself. He wished he’d tucked a bottle of brandy away in the house. But he was trying to keep his drinking down to a dull roar.

Too bad the wine in the basement was off. Be crazy to drink the stuff anyway…

* * *

HE PUTTERED AT HIS DESK, ORGANIZING HIS COMPUTER files, sending out e-mails to colleagues who might want to rent office space. Making the occasional note on Roman Boxer. The late November wind hissed outside; the windows rattled, the furnace vents rumbled and oozed warm air. He wished he’d asked Leah to work late. The big old house felt so empty it seemed to mutter to itself every time the wind hit it.

About 9:30, Fyodor’s cell phone vibrated in his pants pocket, making him jump. Like a snake.

Fyodor reached into his jacket and fumbled the phone out—his hands seemed clumsy tonight. “Hello?”

“You forgot me…” It was his mother’s smoky voice—a bad connection, other voices oscillating in and out of a sea of static in the background.

“Mom. How did I…? Oh. It’s that night?” It was his mother’s night to call him. She must have called his home first.

“You bought the house…”

“Yes—thanks for the tip. I sent you a note about it. You’ve got a good memory. So long ago you were selling houses. I’m hoping if I can rent out the other rooms as offices it’ll more than pay for the mortgage… You still there? This connection…”

“I was born…” Her voice was lost in the crackle. “…1935.”

“Right, I remember you were born in 1935—”

“In that house. I was Catholic. Lived there till I got married. Your father was Russian Orthodox. Father Dunn did not approve. Father Dunn died that year…” Her voice sounded flat. But it was difficult to make out at all.

He frowned. “Wait—you were born in this house? I’m sure you showed me a house you were born in—it was in Providence, but… it was an old wreck of a place… I don’t recall where… I was a kid… But then the agent said they restored it…” Could this really be that house?

“…Through sunken valleys on the sea’s dead floor,” she said, as the wind howled at the window.

“What?”

The phone on his desk rang. He jumped a little in his seat and said, “Wait, Mom…”

He put the cell phone down, answered the desk phone. “Dr. Cheski…”

“Fyodor? You weren’t at home… here you are!” It was his mother. Coming in quite clearly. On this line. “You need to talk to that psycho Psych Tech, he’s following me around the ward…”

Sleet rattled the window glass. “Mom… You playing games with their phones there? You get hold of a cell phone? You’re not supposed to have one.”

On impulse he picked up the other phone. “Hello?”

“They tolled but from sunless tides…” Then it was lost in static—but it did sound like his mother’s voice, in a kind of dead monotone.

Monotone—and now a dial tone. She’d hung up.

He put the cell phone slowly down, picked up the other line. “What, Mom, have you got a phone pressed to each ear?”

“You sound more like a patient than a psychiatrist, Fyodor. I’m trying to tell you that the ‘Psycho’ Tech who claims he works here is… What?” She was speaking to someone in the room with her now. “The doctor said I could call my son… I did call earlier; he wasn’t at home…” A male voice in the background. Then a man came on the line, a deep voice. “Is that Dr. Cheski? I’m sorry, doctor, she’s not supposed to use the phone after eight. I could ask the night nurse—”

“No, no, that’s all right—does she have a cell phone too? It seemed like she was calling me on two lines.”

“What? No, she shouldn’t have one… Oh, there she goes, I have to deal with this, doctor… But don’t worry, it’s no big problem, just her evening rant, yelling at Norman…”

“Sure, go ahead.”

He hung up. Picked up the cell phone. Put it to his ear.

Nothing there. He checked to see what number had called him last. The last call was from Leah, two days before.

* * *

NEXT MORNING, A COLD BUT SUNNY WINTER DAY, Fyodor dropped by the ward, at the facility across town. A bored supervisory nurse waved him right in. “She’s in the activities room.”

His mom wore an old Hawaiian-pattern shift and red plastic sandals, her thin white hair up in blue curlers; her spotted hands trembled, but they always did, and she seemed happy enough, playing cards with an elderly black woman. Someone on a television soap opera muttered vague threats in the background.

“Mother, that house you suggested to Aunt Vera for me—did you say you were born there?”

Mom barely looked up when he spoke to her. “Born there? I was. I didn’t say so, but I was. Don’t cheat, Maisy. You know you cheat, girl. I never do.”

“Did you call me twice last night, Mom? Talk to me twice, I mean?”

“Twice? No, I—but there was something funny with the phone, I remember. Like it was echoing what I said, getting it all mixed up. Hearts, Maisy!”

“You remember reciting poetry on the phone? Something about tides?”

“I haven’t recited poetry since that time at Jimmy Dolan’s. Your Dad got mad at me because I climbed up on the bar and recited Anais Nin… What are you laughing at, Maisy, you never got up on a bar? I bet you did too. Just deal the cards.”

He asked how things were going. She shrugged. For once she didn’t complain about Norman the Psych Tech. She seemed annoyed he’d interrupted her card game.

He patted her shoulder and left, thinking he must have misheard something on the cell phone. Perhaps some kind of sales recording.

Suggestion. The lonely house, the odd story from Roman. Auditory hallucination?

It wasn’t likely he’d be bipolar like his mother—he was thirty-five, he’d have had symptoms long before now. He was fairly normal. Yes, he had a little phobia of cats, nothing serious…

He got back to the office a few minutes late for his first patient. He had six patients scheduled that day; four neurotics, one depressive, and a compulsive finger biter. He listened and advised and prescribed.

A few days later—after Roman signed numerous waivers—Fyodor was sitting beside Roman’s bed, in the guest room, with its repaired lock, waiting for the drug to take hold of his patient.

Roman was lying on the coverlet, eyes closed, though he was awake. He looked quite relaxed. He wore a T-shirt and creased trousers, his blazer and tie and Arrow shirt folded neatly over a chair nearby, the shiny black shoes squared under it. His arms were crossed over his chest; his mother had provided the warm slippers on his feet. There was a small bandage on his right arm, where he’d been injected. The furnace was working full-bore, at Roman’s request, and the room was too warm for Fyodor’s liking.

On a cart to one side was the tape recorder for the session, a used syringe, and the little tray with the prepared syringes for adverse reactions. Superfluous caution.

Leah entered softly, caught Fyodor’s eye, and nodded toward downstairs, silently mouthing, “His mother?”

Fyodor shook his head decisively. No monitoring mothers. Roman was of age.

“I do feel a pleasant… oddness,” Roman murmured, his eyes fluttering as Leah left the room.

“Good,” Fyodor said. “Just relax into that. Let it wash over you.” He switched on the tape recorder, aimed the microphone.

“I feel… sort of thirsty.” His eyes closed; his hands dropped loose, occasionally twitching, at his sides.

“That will pass… Roman, let’s go back to that experience by the ocean, a little over a year ago. You said after that, you were remembering a white room, with a nurse. Could we talk about that again?”

“I…”

“Take your time.”

“…She holds my hand. That’s what I remember about her. The soft pressure of her hand. Trouble breathing—a pressure, a pushing inside me, crowding my lungs. And then—my very last breath! I remember thinking, Is this indeed my last breath? Gods, the pain in my belly is returning, the morphine is wearing off… They say it’s intestinal cancer, but I wonder… Perhaps I should try to tell the nurse about the heightened pain. She’s sweet, she won’t think me a whiner. The others here are more formal, but she calls me Howard… I feel closer to her than I ever did to Sonia… my own little Jewish wife, ha ha, to think I married a Jew, and my closest friend, for a time, before he got the religion bug, was Dear Old Dunn, a Mick… I want to raise the nurse’s hand to my lips, to thank her for staying with me. But I can’t feel her hand anymore. I’m floating over her… There’s a voice, an inhuman guttural voice, calling me from above the ceiling—above the roof. Above the sky. I must ignore it. I must go away from there, to find something, something to anchor me safely in this world… I want to tell my friends I am all right… I drifted, drifted, found myself in front of Dunn’s house… There is a cat, heavy with pregnancy, curled up under the big elm tree. I love cats. Feel drawn to her. That calling comes again, from the deep end of the sky. I need to anchor. The cat. I fall… fall into her. The warm darkness… then sounds, the scent of her milk and her soft belly… light!… and I remember exploring. I was exploring the yard… the big tree, overshadowing me, days pass, and I grow… the sweet mice scurrying to escape me…”

Fyodor had to lean close to hear him.

“Oh! The mice taste sweeter when they almost escape! And the birds—they seem happy to die under my claws. Their eyes, like gems… the light goes out… the gems fall into eternity… mingle with stars… I can scarcely think—but my body is my thought as I patrol the night. I pour myself through the shadows. The other cats—I avoid them, most of the time. If I feel the urge to mate, I go into the house… this house!… through the back door… the girl lets me in… I know what a girl is, what people are, I remember that much. I know there is food and comfort there. I rub against the girl’s legs, climb onto her lap. I will let my embers smolder here. She admires my golden eyes. The girl tells her mother, and Father Dunn, who has come to visit, that the cat understands everything she says. When she says follow, the cat follows. She tells them, ‘I think it understands me right now! It is not like other cats…’”

Fyodor shook his head. This was not going as planned. Roman should be incapable of fantasizing under the influence of this drug; the formula was related to sodium pentothal, but more definitive; it had a tendency to expose onion-layers of memories, real memories… but a memory of being a cat? Was Roman remembering a childhood incident in which he’d imagined being a cat?

“How…” Fascinated, Fyodor cleared his throat, aware his heart was thudding. “How far back do you remember… before the white room—and before the cat?”

Roman moaned softly. “How far… how deep… the night-gaunts… I have come to this house to see Dunn. Of all my friends in the Providence Amateur Press Club, he was the one I trusted the most. Curious, my trusting a Mick—I sometimes sneer at the Irish in the North End, but even so, I love to work with dear old Dunn on his little printing press, in the basement of that magnificently musty old house. I am even tempted to take him up on the wine his father kept in that hidey-hole down there. But I never do. Dunn loves to cadge a little wine from his father’s bottles. Makes up the difference in grape juice. The old Irish rogue conceals the bottles from his wife, she doesn’t like him drinking… wine from Italy, a local Italian priest got for him… dear old Dunn! I even ghostwrote a little speech he made… ghostwriter, wondrous and most whimsical to think of that term, considering how long I wandered, here, from house to house in Providence, afraid of the Great Deep that yawned above me when I breathed my last. Gone. Did anyone notice?” He made a soft rasping moan. “What will people remember of me? If anything they’ll remember the intellectual sins of my youth. But why should people remember me? I’m sure they won’t… If I could tell them what I saw that day, on my trip to Florida! Getting out of the bus, on the South Carolina coast, an interval in the bus trip… my last real trip, in 1935 it was… driver told us the bus would be delayed more than an hour… there’s time to visit the lighthouse on the point near the station. Determined to get to know the ocean. Wanting to go against my own grain. But you can’t grow the same tree twice. Yet I writhe about, trying to change the pattern. I will go to sea, until I make peace with its restless depths. Despite what I told Wandrei—or because of it. I’ll show them I’m more than the polysyllabic phobic they think me. Found the lighthouse—tumbledown old structure, seems to have been fenced off… a broken spire… what a shame… there’s been a storm, I can see the wrack from the sea mingled with its ruins… the breakers have shattered the lower, seaward wall of the lighthouse… there, is that a hollow beneath it? I clamber over fence, over slimed stones, drawn by the mystery, the possibility of revealed antiquity… Perhaps the lighthouse was built on some old colonial structure… Look here, a hollow, a cobwebbed chamber, and within it a sullen pool of black water—its opacity broken by a coruscation of yellow. What could be glowing, sulfurous yellow, within the water of a pool hidden beneath a lighthouse? It’s as if the lighthouse had one light atop and a diabolic inverse sequestered beneath. There, I stare into it and I see… something I’ve glimpsed only in dreams! The tortured spires, the cracked domes, the flyers without faces… I’m teetering into it… I’m falling—swallowing salt water. Something writhes in the water as I swallow it. An eel? An eel without a physical body. Yet it nestles within me, biding, whispering…

“Darkness. Walking…

“Back on the bus, looking fuzzily about me. How did I make my way back to the bus? Cannot remember. The driver solicitous, asking, ‘You sure you’re all right, sir? You’re wet clear through.’ I insist I’m well enough. I take a few minutes to change my clothes in the station restroom. The other passengers are exasperated with me, I’m delaying them even further. I feel quite odd as I return to the bus. Must have struck my head, exploring that old lighthouse. Had a dream, a nightmare—can’t quite remember what it was… dream of something crawling into my mouth, worming through my stomach, down to my intestines… something without a body as we know them… Quite exhausted. I fall asleep in my seat on the bus and when I wake, we’re in northern Florida.”

Fyodor glanced at the tape recorder to make sure it was going. Had he administered the drug wrongly? This could not be a memory—Roman could not possibly remember 1935. Still, it was surely a doorway into Roman’s unconscious mind. A powerful mind—a writer’s mind, perhaps. A narrative within a narrative, not always linear; a nautilus shell recession of narrative…

Eyes shut, lids jittering, Roman licked his lips and went hoarsely on. “…trip to Cuba canceled but still—Florida! Saw alligators in the sluggish green river—seemed to glimpse a slitted green eye and within that eye a sulfurous light shining from some black sky… A great many letters to write on the bus back, handwriting can scarcely be legible… oh, the pain. In the midst of my midst, how it chews away. Cursed as always with ill health. Getting my strength in recent years, discovering the healing power of the sun, and then this—the old flaw chews at me from within now. I fear seeing the doctor. Nor can I afford him. Little but tea and crackers to eat today… can’t bear much more anyway, the pain in my gut… I seem to be losing weight… R.E.H. is dead! Strange to think of ‘Two-Gun Bob’ taking his own life that way. He should have been a swordsman, striking the life from the faceless flyers when they struck at him in some dire temple—not muttering about his Texas neighbors, not stabbed through the soul by his mother’s passing. We should not be what we are—we were all intended to be something better. But we were planted in tainted soil, R.E.H. and I, tainted souls blemished by the color out of space. I wrote from my heart but my heart was sheathed in dark yellow glass, and its light was sulfurous. So much more I wanted to write! A great novel of generations of Providence families, their struggles and glories, their dark secrets and heroics! I can be with them, perhaps, when I die—I will become one with the old houses of Providence, wandering, searching for its secrets… And I refuse to leave Providence, when I gasp my last…

“The sweet little nurse takes my hand, more tenderly than ever Sonia did. But God bless Sonia, and her infinite patience. If only… but it’s too late to think of that now. The nurse is speaking to me, Howard, can you hear me?… I believe we’ve lost him, doctor. Pity—such a gentlemanly fellow, and scarcely older than… I can’t hear the rest: I’m floating above them, amazed at how emaciated my lifeless body is; my lips skinned back, my great jutting jaw, my pallid fingers. I’m glad to be free of that body. There’s no pain here! But something calls me from the darkness above. Is the light of Heaven up above? I know better. I know about the opaque gulfs; the deep end of the sky. The Hungry Deep. I will not go! I will go see Dunn! Yes, dear old Dunn. Something so comforting about the company of my fellow Amateur Pressmen. I’ll find my way to Dunn’s house… Here, and here… I flit from house to house… is it years that pass? It is—and it doesn’t matter. I drift like a fallen leaf along the stream of time, waft through the streets of Providence. How the seasons wheel by! The yellowing leaves, the drifting snow, the thaw, the tulips… I see other ghosts. Some try to speak, but I hear them not… There—Dunn’s house! I’ll see if he’s still within. But no. Father Dunn has moved on. There is the little Irish girl, adopted by the Dunns. And the cat, her cat, fairly bursting with kittens. Oh, to be a cat. And why not? The mice… sweeter when they run… I speak to the girl… she shouts in fear and throws something at me. She chases me from the house!

“What’s that? One of the great metal hurtlers in the street! Truck’s wheel strikes me, wrings me out like a wet rag… Agony sears… I float above the truck, seeing my body quivering in death, below me: the body of the cat. But I am at peace, once more, drifting through Providence. Let me wander, as I did once before… let me wander and wait. Perhaps next time I’ll find something more suitable. Someone. A pair of hands that can fashion dreams…

“The Great Deep calls to me, over and over. I won’t go! My ancient soul has strength, more strength than my body ever had. It resists. I remember, now, what I saw in the ruins of that old lighthouse—under its foundations: the secret pool, the shamanic pool of the Narragansett Indians. A fragment of a great translucent yellow stone was hidden there—a piece of a larger stone lost now beneath the waves, once the centerpiece of a temple in the land some called Atlantis.

“The cat-eye stone struck from Yuggoth by the crash of a comet—whirling to our world, where it spoke to the minds of the first true men; gave the ancients a sickening knowledge of their minuteness, the vast darkness of the universe.

“It has been whispering to me since I was a child—my mother heard it, she glimpsed its evocations: the faceless things that crawled from it just around the corner of the house. She’d tell me all about them, my dear half-mad mother Sarah. She had visited that place, and heard its whispering. And that seemed to plant the seed in me—which grew into the twisted tree of my tales…

“I drift above the elm-hugged street, refusing to depart my beloved Providence. But the call of the Great Deep is so strong. Insistent. I hear it especially loudly when I visit Swan Point Cemetery. No longer summoning—now it is demanding.

“There is only one way free, this time—I must hide within someone… I must find a place to nestle, as I did with the cat… Here’s a woman. Mrs. Boxer is with child. I feel the heartbeat, pattering rapidly within her—calling to me… I go to sleep within her, united with him, the tabula rasa…

“I wake on the beach, full-grown. I cannot quite speak. I cannot control my body. It moves frantically about, speaking into a little invention, from which issues a voice. ‘Why, what do you mean?’ says the voice. ‘This is your mother, for heaven’s sake! Whatever are you about, Roman?’ If only I could speak and tell her my name. A voice comes from my mouth—but it is not my voice, not truly. I want to tell her my name. I cannot… My name…”

Fyodor leaned closer yet. The next words were whispered, hardly audible. “…is Howard. Howard Phillips. Howard Phillips Lovecraft…”

Then Roman was asleep. That was the natural course of the drug’s effects. There was no waking him, now, not safely, to ask questions.

Stunned, Fyodor sat beside Roman, staring at the peacefully sleeping young man. Seeing his eyelids flickering with REM sleep. What was he dreaming of?

* * *

FYODOR HAD GROWN UP IN PROVIDENCE. EVERYONE here had heard Lovecraft’s name. Young Fyodor Cheski had his own Lovecraft period. But his mother had found the books—he was only thirteen—and she’d taken them away, very sternly, and threatened that he would lose every privilege he could even imagine if he read them again. She knew about this Lovecraft, she said. Things whispered to him—things people shouldn’t listen to.

It was one of his mother’s fits of paranoia, of course, but after that Fyodor was taken with a more modern set of writers, Bradbury and then Salinger—and a veer into Robertson Davies. Never gave Lovecraft another thought. Not a conscious thought, anyway.

His mother, in her manic periods, would babble about a cat she’d had as a small girl, a cat that used to talk to her; she’d look into its eyes, and she’d hear it speaking in her mind, hissing of other worlds—dark worlds. And one day she could bear it no more, and she’d driven the cat into the street, where it was hit by a passing truck. She feared its soul had haunted her, ever since; and she feared it would haunt Fyodor.

A chill went through Fyodor as he realized he had fallen entirely under the spell of Roman’s convoluted narrative. He had almost believed that this man was the reincarnation of the writer who’d died in 1937. Perhaps he did have a little of his mother’s… susceptibility.

He shuddered. God, he needed a drink.

He thought of the wine in the basement. It was still there. Hal said it was vinegar, but he hadn’t tested the other bottles. Fyodor had a powerful impulse to try one out. Perhaps he’d see something down there that would spark some insight into Roman…

His patient was sleeping peacefully. Why not?

He went downstairs, to find that Roman’s mother, anxious, had gone to see her sister. Leah was yawning at her desk.

He looked at her, thinking he really should take her out, once, see what happened. She’s not dating anyone, as far as he knew.

He almost asked her then and there. But he simply nodded and said, “I’ll take care of things here. He’s sleeping… he’ll stay the night… You can go home.”

He watched her leave, and then turned to the basement door, remembering the agent had mentioned the house had belonged to the Dunn family for generations. Doubtless Roman had found out about the house’s background, somehow, woven it into his fantasies. Probably he was a Lovecraft fan.

Fyodor found the switch at the top of the steps, switched on the light and descended to the basement. Really, that bulb was too bright for the basement space. It hurt his eyes. Ugly yellow light bulb.

He crossed to the corner where he’d replaced the cap over the hole in the floor. The crowbar was still there. He pried up the cover of cement and wood—took more effort than he’d supposed. But there were the bottles. How was he to open them?

Why not be a little daring, opening the bottle as they did in stories? He pulled a bottle out and struck the neck on the wall; it broke neatly off. Wine splashed red as blood against the gray concrete.

He sniffed at the bottle. The smell wasn’t vinegary, anyway. The aroma—the wine’s bouquet—was almost a perfume.

The bottle neck had broken evenly. No risk in having a quick swig. He sat on one of the crates, put the bottle neck to his lips, and tasted, expecting to gag and spit out the small sip…

But it was delicious. Apparently this one had been sealed better than the one his friend Hal had looked at. Strange to think it had been here undisturbed all those years—even when his mother had been here. Only once had she mentioned the name of the people who’d adopted her. The Dunn family…

He wanted badly to sit here awhile and drink the wine. Quite out of character—he was more the kind to have a little carefully selected Pinot in an upscale wine bar. But here he was…

Strange to be down here, drinking from a broken wine bottle, in the concrete and dust.

It’s not like me. It’s as if I’m still under the spell, the influence, of Roman’s ramblings. It’s as if something brought me here. Something is urging me to lift the bottle to my lips… to drink deeply…

Why not? One drink more. If he was going to ask Leah out he’d need to be more spontaneous. He could call her up, tell her the wine was better than they’d supposed. Might be worth something. Ask her to come and try some…

He licked his lips—and drank. The wine was delicious; a deep taste, and unusual. Like a tragic song. He laughed to himself. He drank again. What was it Roman had said?

I never used to drink. I wanted to take it up, starting with something old and fine. I want a new life. I desire to do things differently. Live!

Fyodor drank again… and looked up at the light bulb. He blinked in its fierce sulfurous glare, its assaultive parhelion. It seemed almost part of an eye, a glowing yellow eye, looking at him from some farther place…

He stood up suddenly, shaking himself, his twitching hands dropping the bottle—it shattered on the concrete with a gigantic sound that seemed to resound on and on, echoing… and in the echo was a voice. His mother’s voice… the part of her mind that had spoken to him through the sea of static. This time it said something else.