6,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: tredition

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

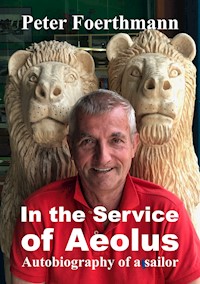

Peter Foerthmann has been the first port of call for bluewater sailors seeking advice in steering matters for decades. His unrivalled expertise - the product of a lifetime developing and manufacturing windvane self-steering systems and contemplating their every complexity - continues to draw enquiries from all over the world. Half a century of experience with both his own boats (several dozen have come and gone over the years) and other people's (Peter has installed self-steering gear for literally thousands of sailors) has left him with a treasure trove of invaluable information to share. This book focuses on the attributes that make a yacht suitable for bluewater passagemaking. It examines the differences between traditional and more recent design conventions and their implications for offshore use, explains why some modern boats may not be such a good idea for long-distance cruising and gives sailors in search of a timeless home from home plenty of practical advice about the features to look out for (and the features to avoid) if they want serious fun on the oceans with as little as possible left to chance.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 124

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Peter Foerthmann

Boatbuilding - Yesterday and Today

Trends, preferences and priorities

Copyright: © 2020 Peter Foerthmann

From German into English: Chris Sandison

Cover & Set: Sabine Abels | e-book-erstellung.de

Cartoons: Inga Beitz–Svechtarov

Fotos:

Peter Foerthmann: 14, 43, 47, 50, 57, 59, 60, 62, 61, 63, 75, 80, 100, 122,128

24, Edward Burnett

38, René Bornmann

52, Sebastian Groth

67, Kai Greiser

68, Jörg Jonas

94, Jimmy Cornell

102, Harry Schank

110, 128, Sybille + Christian Uehr

123, Christian Heusinger

126, Sepp Koch

154, Rainer Woehl

Publisher:

tredition GmbH

Halenreie 40-44

22359 Hamburg

978-3-347-21813-0 (Paperback)

978-3-347-21814-7 (Hardcover)

978-3-347-21815-4 (eBook)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher and author.

Content

FOREWORD

BOATBUILDING

Materials and processes

Lifetime and maintenance requirements

Rationalisation: the key to creating value

Custom builds versus mass production

Use, intended and actual

Boatbuilding and the market

Value and resale

Class associations

The second-hand market

Metal yachts

Cost of sales

THE RUDDER

Watch out for the crunchy bits …

Advice: USA versus EU

A return to reason

Easy on the eye

THE STEERING

Tiller steering

Wheel steering

The Golden Globe Race

Treacherous waters

Emergency tiller

Drive systems

Shaft drives

Z-drives and saildrives

Saildrives

The hard facts

WHY “ACHILLES‘ HEELS“?

Things that go bump in the night

Murphy legislates

Soft impacts

TRANSOM ORNAMENTS

Windvane self-steering system

Time at the back

Local strength

Swim ladder

Gangway

Bathing platform

Davits

Dinghy

Outboard motor

Antennas

Wind generator and solar panels

Antenna arch

Bimini

Life raft

Hydrogenerator

The full house

BLUEWATER ADVICE

Thou shalt advertise

Principles

THE PILLARS OF INFORMATION PROCUREMENT

Sponsorship

Know-it-alls

The media

Bluewater seminars

The paywall

THE DREAM

Sailing: fun or serious business?

IN CONCLUSION …

BOATBUILDING – FROM COTTAGE INDUSTRY TO MASS PRODUCTION

Clearly sailing could never have become widely accessible as a sport without the introduction of mass production in glassreinforced plastic. The smaller the boat, the bigger the potential market open to it and hence the more units to be sold. The Optimist and Laser dinghies have been churned out in their millions and while yachts have never shifted in these numbers, their extra features – everything from heads to an engine – make them far more interesting in terms of the value to be extracted per unit.

When yacht production first began to move onto something approaching an industrial footing, the small number of manufacturers offering boats at shows in Europe could sell dozens of each model every time they exhibited. I really do mean dozens too. Back in the 1970s I would often pass the evenings during the Interboot boat show in Friedrichshafen playing cards with Peter Schmidt, the man behind the Sirius yard. One year the weeklong show brought him more than 30 orders (the celebrations left him hard pushed to stay upright, never mind cope with a hand of cards).

The Seventies and Eighties were gold rush time as sailors beat a path to the boatyard gates and demand (and sales) soared. Brian Meerloo and his Cobramold UK team in England built thousands of their Leisure yachts, for example, back when nobody seemed to worry about breathing in styrene vapour and extractors were unheard of.

Coincidentally it was to Brian that the founder of my company, John Adam, turned in 1968 when he needed something small and seaworthy. The Leisure 17 Brian supplied took John West, West and West some more until, having fallen asleep and run aground, he found himself on the beach in Cuba. It was probably while cooling his heels in one of Castro‘s prisons that he made the decision to set up Windpilot: the first model had after all passed its test with flying colours (keeping watch – then as now – not being a part of its remit). John‘s story created a sensation at the time in Germany and all the marketing professionals in the world could not have conceived of and coordinated a better market launch for Leisure yachts. The brand retains a special aura to this day, with over 4,000 Leisures sold and almost all of them still in existence. But I digress …

The number of people eager to get afloat was simply too high for traditional production methods and craftsmanship to cope. Consumers were no more inclined to wait for satisfaction then than they are now: once they felt the itch, they wanted deck beneath their feet and pronto. When it comes to impatience, children on Christmas Eve have nothing on grown men and women waiting for a new boat to arrive. Suddenly even extra costs become acceptable if they promise to bring delivery forward by a few days.

The transformation in the nature of boatbuilding precipitated by these pressures was dramatic. The process was – almost literally – turned upside down (or inside out, depending on your point of view) and ever since, boats have been built the wrong way around: today everything starts with the skin and not the bones. Henry Ford had his first assembly line up and running by 1914 but it was not until a good half a century later that the boatbuilding industry first sat up and took notice. People had other concerns in the hectic postwar years.

Originally the hull of a boat was a very complex assembly: to keel and keelson, stem, sternpost, stringers, deck beams, floor timbers and ribs were added planks as thick as a seaman‘s thumb and the whole thing was bolted, nailed and glued together, caulked and sealed repeatedly and then finally treated to several rounds of painting and polishing to create a thoroughly robust and watertight structure. All of which took some time!

A finished hull of this nature came ready to sail; there was no need for extra interior reinforcement or fittings to stiffen the structure and dissipate the working loads. To keep the weight down, racing yachts often started life with nothing below but pipe berths and were only fully furnished at a later date – in preparation, perhaps, for a second life as a cruising boat – once deemed uncompetitive. Whether to hit the racecourse with a crack crew or embark family and friends and concentrate on seeing and being seen was a matter for the owner: the yachts were tough enough for both lives – in fact most them still are.

In those days the cost of the hull made up an eyewatering proportion of the overall price of the boat. Boatbuilders were craftsmen, not magicians, and bending wood takes time (not that man hours were at all expensive in that era of course). Rationalising hull construction became the logical way to go – and it is here that the rot set in!

Materials and processes

Once a GRP female mould had been produced, readymade boat shells could be turned out one after the other like so many bread rolls in a process that suddenly no longer needed the expertise of skilled boatbuilders. No sooner had one hull cured than it was lifted from the mould to make way for the next.

Mass production techniques were not adopted in all areas of the manufacturing process at the same time, however, and it is characteristic of the modern classics that although they have a GRP hull, they were still fitted out by craftspeople: skilled boatbuilders still had a hand – and earned a crust – in their creation. Also no secret is the fact that older GRP boats tend to be considerably more solid, because their stringers, floor timbers and wooden interior components are all laminated into the hull. The resulting structure is very stable, especially since the stringers and bearers are bonded faceon and the interior components edgeon. The three Hanseat boats I have owned were typical products of this time, when sailing boats were still seen and not heard: perfectly quiet to sail whatever the wind and sea state and no creaking from the deck – even when the summer hoards stampeded across on their way from the far end of the raft to the bar.

Modern classics enjoy great popularity today because of the way they combine the beautiful lines and traditional craftsmanship of old with modern materials. And, at a more basic level, because of the way they allow families – even those members with a more sensitive nose – to take to the sea without the damp reek of stale air and musty socks that tends to pervade the more traditional of traditional craft. There is more to boatbuilding than right angles; indeed their very curvaceousness accounts for a big part of the appeal of those striking little ships whose lines alone set hearts pounding and bank accounts quaking. On a more practical level, the distinctive interior typical of the modern classics also ensures that no matter how soundly you slept, you quickly remember that you are on the boat and not in the house. Right angles simply never featured in this era, which for me explains much of its charm and elegance.

The visual language of traditional design was always emotional: function followed form and not vice versa. Today the mainstream marches to the beat of a different drummer, with aesthetic concept and product shaped by marketing diktats and design vocabulary serving only to ensure brand recognition and distinctiveness. Sometimes even a straightforward coloured stripe will suffice.

The boats of the past were undoubtedly more robust. They had a backbone and ribs, meaning they were better armed against ramming, stranding, grounding and other extreme encounters, and carried their rudder firmly mounted and safely tucked away in the sweet spot at the trailing edge of the keel. Modern yacht design specifies no such backbone. It has been spirited away to be replaced, here and there, with other structural members because space, increasingly, takes priority over everything else. Much the same thing has happened with cars: once upon a time they had a distinct chassis but now each component seems to be supported by nothing more than the components around it.

Interior shells and moulded parts have increasingly driven traditional boatbuilding out of interior construction too on the basis that separate units and components can be massproduced rapidly and installed (glued!) inside a bare hull equally quickly. Boats today are built in a modular fashion, which simplifies customizing and cuts costs. Moulded components can also incorporate rounded edges and corners at no extra cost to suggest at least a token element of design flair.

Today hulls are reinforced in critical areas with bulkheads, interior shells, longitudinal stringers and space frames to make sure that when the boat is lifted out, the keel comes too, that the engine doesn‘t slowly make its way up the boat while motoring and that the pressure transmitted from the mast above when sailing close-hauled does not leave hapless crewmembers marooned in the heads. The most extreme designs include additional metal structures to distribute the loads.

Some would have us believe that modern boats are more solid than ever, but do their claims hold water? Space has become a more compelling argument and the obvious response has been to do away with the traditional foundation of a strong hull – its frame and ribs – without putting anything obvious in its place.

Sailors and families flock to the resulting space(ous) ships like moths to a candle, for it seems the number of berths has become the measure of all things (and has a not insignificant effect on the price). A large proportion of current designs came into being with the requirements and imperatives of the charter industry to the fore too, of course, and they sell bunk space by the week!

Did anyone ever stop to consider how this wonder came to pass? Does anyone seriously spend any time thinking about how much – if any – effective loadbearing structure there is left behind that smart interior shell? Perhaps it‘s all a matter of perspective (after all, what we don’t know might not hurt us, right?). There used to be a hull at one of the big boat shows that had been sliced in half longitudinally and I couldn’t help noticing just how little substance there would be between the sailor asleep in a bunk of a heeling yacht and the fish swimming past outside. This cutaway half-hull provided the backdrop for countless Bobby Schenk seminars, so perhaps – perhaps – I wasn‘t the only one to wonder at the eggshell separating the wet from the dry.