6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

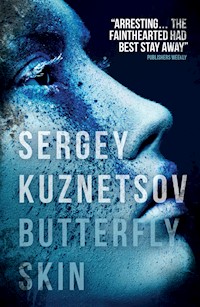

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

On the streets of Moscow, a vicious serial killer stalks his female victims. Ksenia, an ambitious young editor of an online newspaper, seeks to entrap him and further her own career. But her preoccupation with the crimes reflects her unconscious fascination with the sexual savagery of the murders and her own dark desires. She becomes obsessed with the unknown and seemingly unknowable killer... and he with her.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

About the Author

About the Translator

Also Available from Titan Books

Butterfly Skin Print edition ISBN: 9781783290246 E-book edition ISBN: 9781783290253

Published by Titan Books A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd 144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: September 2014

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 2014 by Sergey Kuznetsov. All rights reserved. Translation copyright © 2014 by Andrew Bromfield. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

I wanted to dedicate this book to two of my friends. They refused to read it and said they didn’t want their names to be associated with it. So I dedicate the novel to my wife, Katya. She has absolutely nothing at all to do with this story, but her love helps me survive in this beautiful world.

As Joan was burning, she looked round and said: “See, I have taken off my dress and shaved my head. See, now I am not hiding anything, The second dress I tear off is my skin. Pluck at the veins and feel the flesh There is only a single moment left.”

Alexander Anashevich

1

YOU ARE TEN YEARS OLD, OR PERHAPS YOUNGER. YOU are riding in the subway with your mother, looking toward the front of the train through the transparent doors of the cars. Suddenly you notice that somewhere up ahead, something has happened: people jump to their feet in a strange state of alarm and run back against the movement of the train, as if they are fleeing from something, until they reach the locked doors between the cars – and they tug and tug at the handles… But then their faces contort as panic sweeps over their normal features like a wind driving ripples across the surface of a pond. Something invisible is approaching, something nameless and formless, more terrible than death, more horrible than a nightmare. Something they have known about and tried to forget all their lives.

And now the front cars slowly enter the transparent wall of condensed horror, but you can no longer bear to look at the faces flattened against the glass, the mouths opened in mute screams, the eyes bulging out of their sockets – you turn your gaze to the passengers still untouched by the horror, sitting in the nearest cars, and again you see that faint shadow of anxiety change to panic, you see them jump to their feet and run, run and pound on the locked glass doors… and the invisible wall gets closer and closer, advancing implacably, like in a dream. But you don’t leave your seat, you don’t feel for your mother’s hand, you just think with relief that it will all soon be over.

These are only my fantasies. I was ten years old, or perhaps younger, and I often imagined this scene. As I got older, however, everything changed, it was no longer a wall, but more like a wave, a wave from a distant cold sea that froze the blood, a wave that swept along the train from the front to the final car. But now no one jumps up from his seat, everybody sits there until the shuddering contorts their faces like a hand crumpling a used tissue.

Yes, as a boy I certainly had a rich imagination. When I grew up a bit, I started telling other people what I used to believe when I was a child: that there was a place in the subway where hell seeped through into the tunnel in a thin layer of horror – and the trains passed through it so quickly that only really sensitive people noticed. I used to give the girls a suggestive look at the words “really sensitive.” Sometimes it worked.

Now I know it has nothing to do with sensitivity. It is my own personal hell, my personal horror, my concentrated nightmare. The passengers will never have any idea about it, nothing will distort their faces, not a single hair will shift out of place. I am the only one who notices the signs, the only one who senses the approach, the only one who understands the language of the things and objects that warn me in vain of the approach.

The fine hairs on woolen scarves stand up on end, leather coats are covered with fine cracks, feathers creep out of down-filled jackets as if seeking escape, stockings grip legs even tighter, the colors drain out of the advertising posters, any moment now the glass in the windows of the car will rain down on to the seats, the handrails cringe under my fingers, the doors scream in horror. Everything stops, as if time has been switched off, the clatter of the wheels fades away, and suddenly you can hear what the two girls standing by the closed doors are talking about. One is small and skinny, with tousled black hair, the other is graceful, with long legs and light hair. Just a minute ago they were laughing and nudging each other as they discussed how they were going to spend their first pay cheque, but now their faces have aged ten years, and you hear the light-haired one say: “I can’t believe she’s gone,” and see her wipe her eyes with a handkerchief as contorted as your own face, and the smaller one takes hold of her hand and replies: “And I still can’t even cry.”

And then the sounds get duller, space curls up round the edges of your vision like old wallpaper on a damp wall and everything goes dark before your eyes, as if the entire world is hiding behind those whirling black spirals: the sudden surge overtakes you, sweeps over you. You can’t breathe, the outlines of your body blur within this black cocoon as despair and hopelessness congeal: reach out your hand and you can touch them.

The old horror of childhood? No, this is not horror, it is anguish, concentrated anguish, a stifling feeling, a constant ringing in the ears, the flow of your own blood, darkness, darkness – the dark cloud will hang on the folds of your clothes, cling to the contours of your face, to the hairs stuck to your forehead, to the gnawed ends of your fingers.

You carry this cocoon, this cloud, with you as you leave the subway. You will make conversation, discuss work, come to decisions, write business letters. You will flirt with girls, play with your children, smile at people you know, try to live the way you always do. But on days like this, if you reach out your hand, you can touch the boundary of hell: suffering oozes out of doors slightly ajar, flows across the walls of buildings, crunches under your feet like broken glass; every gesture causes pain, every touch makes you shudder convulsively; your skin dissolves, leaving only the naked bleeding flesh, just barely covered by the gray cloud of anguish.

Days like this are excruciating for me. In order to cope somehow, I start remembering the women I have killed.

2

AN ELECTRIC BEEPING. NOT A METALLIC CHIME, NOT the tinkling of a small bell, but the artificial trill of a microchip. The signal of an alarm clock bought in IKEA, a child’s alarm clock covered in bright-colored soft plush, with a big dial and yellow hands. Out from under the blanket comes a hand, a thin hand, with a silver ring on the index finger, an arm with a faint scar just above the elbow. The little palm swats a blue velvet pimple, the ringing stops, the arm disappears.

You don’t want to open your eyes, you don’t want to wake up. As if through half-closed eyes we see the corner of a pillow, a braid of hair, the edge of a blanket. You want to sleep, with your head hidden under the blanket, swaddled up as tight as you can get, hidden away, as if you were nestling inside a cocoon, sleeping like that forever, ever since you were a child.

“Good morning!”

Who did you say “good morning” to in that muffled sleepy voice? There’s no one else in the room. A patch of yellow sunlight – it matches the hands of the clock – on the bright-colored kilim by the bed, an open laptop with its matte screen reflecting nothing, a fluffy pink rabbit lurking between the wall and your body. Good morning, as if you were trying to wake yourself up. Yes indeed, good morning, Ksenia.

Yes, your name is Ksenia, you live in a rented flat, cheap, found through friends. That’s about a third of your salary, everything’s very Western, the way grown-ups live. You’re completely grown up now, twenty-three years old, you work in the news department of the internet-newspaper Evening.ru. E-v-e-n-i-n-g dot ru, not a very well-known newspaper, second flight – maybe you’ve never heard of it, but our news section is good.

Outside the window there is rain, outside there is December, gray sky, not a single snowflake. You only imagined the patches of sunlight in your sleep. Slip your feet into the fluffy slippers, pick the white dressing gown up off the armchair, push the “Play” button and turn up the volume. The Gotan Project playing a remix of Gato Barbieri. That’s how the morning starts.

On the way to the bathroom you can’t resist looking at your email. Five messages, including four pieces of spam, two of them offering to increase the size of your penis and your breasts. You don’t need either – you don’t have a penis and your breasts are just fine.

What do you look like? Thin, short, with tousled black hair, lips puffy from sleep, big eyes that simply refuse to open in the morning. You look at the fifth message. Aha, from your friend Olya, good that it’s not about work. But then, how could it be about work? You went to bed at three and got up at eight – at that time everyone’s asleep, no one’s writing work emails.

You walk through into the bathroom, turn on the shower and freeze in front of the mirror, trying to put the day together in your mind. What’s in store for us today? The usual stuff first thing in the morning, then a talk with Pasha about money, lunch at the coffee house, Mom’s birthday, she asked you to be there at seven and not be late. You take off the dressing gown with a sigh and look in the mirror, already dewy with condensation: it’s damp, steamy and warm in here, the way you like it.

The bruises on your breasts and shoulders are barely visible, but your thighs – oh, that’s quite a different matter. And the welts on your buttocks sting in the scalding water. Yes, you like your body to retain its memories of your assignations for a long time. You like to be hurt. You have a small collection of various amusing gadgets at home, black leather toys, whips, gags, nipple clamps. On good days you don’t see anything unusual about your preferences. The way you think about it is more or less like this: sometimes I want to dance the boogie-woogie in a club in the Kropotkinskaya district, sometimes I ask someone to beat me and hurt me. Sex is like dancing; the important thing is to have a good partner. That’s the way you think on the good days, but on the bad days you remember that sex is not dancing, and it’s not easy for someone with your tastes to find a worthy partner. It’s not easy, but you cope one way or another. More or less.

But you’re not coping too well, to be honest. You parted company with your last lover a week ago, it’s over between you now – that’s why, instead of the sweet pain of gratification, your skin is smarting with the nagging pain of separation.

You turn off the shower, rub yourself down with a towel and your raw spots ache. Smiling, you walk through into the kitchen and put the kettle on. The music from the other room is almost inaudible. You look at the clock: you still have enough time for a cup of coffee.

This is how the day begins. Outside the window, a colorless sun in a gap between December clouds. Good morning to you, darling Ksenia. Don’t forget to dress warmly, there’s a strong wind today. Don’t forget to take the present for Mom, your cell phone, money, ID, travel pass. Don’t forget – you have a lot to do today, darling Ksenia, take good care of yourself. Ah yes, and the keys too. Don’t forget them, please.

3

AND SO… ONCE UPON A TIME A LITTLE GIRL LIVED with her mommy and daddy, went to the kindergarten, then to school, danced and laughed and never cried. Mommy and Daddy got divorced, school came to an end, the little girl went to work and now, six years later, here she is sitting in a tiny office cubicle with her strong fingers pounding away at a keyboard, her tousled hair more or less held in place by a hair slide, her painted lips pursed in concentration and not a trace of the morning’s relaxed mood left in her voice.

“Ksenia, are we putting the news about Berezovsky at the top or is everybody already pissed off with him?”

“He’s the one who’s pissed off. What else have we got, apart from Berezovsky?”

“I’ll just take a look.”

This is an ordinary day. The Little Lady of the Big House. It’s just a title – Senior Editor of the News Department – a pitiful staff of three, plus the freelancers. True, they’re all a few years older than you, and some even have formal qualifications in journalism. Think of themselves as professionals, shit! Sharks of the pen, jackals of the keyboard, freebooters of the computer mouse. There was a time when you had to have sharp words with them, it’s true, but now you have them all in line, working at full stretch.

Alexei from the next desk asks on ICQ Internet Messenger:

“how are you doing?”

She answers: “ok” and then asks: “when will I have the interview?”

“I’m just typing it up.” Yes, he’s sitting there in his earphones, deciphering it.

Daily work inevitably becomes routine: making sure they choose the right news, correcting mistakes, telling off the young girl translators, deciding who to take commentaries from today. A couple of times a week you end up with good material, something you can really take pride in, not feel ashamed of. But then, you don’t feel ashamed of what you put out every day either, although there’s really not that much to feel proud of, except maybe the successful start to your career: after all, at twenty-three you’re already the department’s senior editor. The boss. It’s funny.

Ksenia likes her job. She enjoys rummaging through the news and she enjoys coordinating, managing and controlling even more. In a few years’ time she’ll be a good manager, although it’s not yet clear where. Maybe she’ll become a genuine senior editor, get into paper journalism, if Putin doesn’t grab all the newspapers the way he’s already grabbed the TV channels. Or perhaps she’ll go into pure IT business. “IT” stands for information technology, and it’s part of everything to do with the internet. In America they like to add the letter “e,” from the word “electronic,” but in Russian it’s not always convenient to add that letter. You definitely can’t add it to the word “business,” for instance. “You know,” Ksenia explained to one of her foreign friends, “the combination ‘eb’ in Russian is the same as ‘fuck’ in English. So you get ‘fuck-business.’ I can’t even say that to one of my friends, let alone my mom.”

Ksenia likes her job. She enjoys feeling confident, successful and prosperous. She likes being able to do everything at once: edit an interview, instant message, look through the news. By twelve they’ll put the first section of material out on the web, and then she can go to the cafeteria with Alexei, read the latest jokes at Anecdote.ru, call in to see Pasha and have a word about money.

* * *

Pasha Silverman, Ksenia’s immediate boss, the editor-in-chief and founder of the newspaper Evening.ru, had no interest at all in journalism until the age of thirty-seven.

He moved from the Chechen capital, Grozny, to Moscow in the late eighties – just in time: first there were no more Russians left in the city, then there were no Chechens, and then the city itself disappeared. By the mid-nineties Pasha was heavily involved in advertising, but during one of the repeated market carve-ups, he got squeezed out of TV and billboards, and by the beginning of the next decade all that remained of his former glory was an internet agency, which was lifted up on the rising wave of the investment boom of 2000.

When Pasha first came to the internet, the major form of advertising was banners – little rectangular pictures at the top, bottom or side of the internet page. If the picture caught someone’s attention, he clicked on the banner with the mouse and found himself on the advertised site. Basically, that was all there was to it. You could take money for the number of people who would see the banner (that was called “pay-for-views”) and for the number of people who clicked on the banner (“pay-for-clicks”). Since then variations had appeared – square banners, pop-up window banners, flash banners and lots of other wonderful technical innovations – but the general principle hadn’t changed. The technology made it possible to show the advert to the right audience on the right site – that was called “targeting” – but basically Pasha made money out of people looking at little pictures on their computer screens and occasionally clicking on them for some reason or other.

Pasha had always believed that dealing in advertising was dealing in something unreal. That didn’t frighten him: it had been explained to him many years before that in mathematics imaginary numbers like the square root of −1 were just as important as ordinary numbers. Trading in advertising in virtual space was a double unreality – and just as the number i, which didn’t exist in the normal scale of numbers, made it possible to solve equations and create graphs, the ephemeral banner advertisement allowed Pasha to consolidate his own business and help others to build theirs. Pasha liked the idea of working with things that weren’t real – perhaps because there wasn’t a single stone left standing in the city where he had spent his childhood.

A couple of years earlier the logic of business development had led Pasha to the idea that it would be good not just to trade in views on other people’s sites, but to have a platform of his own where he could show his own banners. He decided to set up a newspaper, intending at the same time occasionally to publish advertorial, or paid articles, especially since the time for elections was approaching and the political parties and independent candidates were still prepared to pay well for such material – although, of course, not as well as in the nineties, when the elections were really fascinating.

As an advertising man, Pasha was convinced that to get high traffic all you needed was the right kind of promotional campaign. After six months he realized that an online newspaper was not the same as washing powder or a new model of cell phone. The competition in internet media was pretty stiff, and Pasha sacked almost all his editorial staff and took on new people to replace them. One of these was Ksenia, and today Pasha knew it was her energy and talent he had to thank for the large numbers of people who read the news on his site, even if Tickertape.ru did provide much broader coverage.

Ksenia has a sense of style: she can make any banal news story entertaining – news about the economy comes out as a story about urgent daily realities and the experts’ comments sound like providential revelations. Pasha has raised her salary twice during the last year, but now, seeing her sit down in a chair and cross her legs, he regrets that he allowed himself to be sold on the idea. I won’t give her another kopeck, he tells himself, and smiles amiably.

“How’re things, Ksenichka?”

“Fine, thanks,” she replies.

Tousled hair, stubborn lips, strong thin arms wrapped round her knees. She doesn’t like Pasha’s familiar use of a diminutive “Ksenichka” – to everyone else she is just Ksenia, even to her lovers. And she doesn’t allow anyone except Olya to call her by her childhood name “Ksyusha.” Only Olya can pronounce “Ksyusha” in a way that doesn’t remind her of the fifth class at school and mocking children’s rhymes.

But Pasha calls everyone by familiar pet names and he has persuaded her to accept Ksenichka – persuaded, sold, soft-soaped – he told her that he was prepared to address her formally as Ksenia Rudolfovna if she wanted, but he asked her please, please to let him say “Ksenichka” sometimes, because otherwise he wouldn’t be able to do his job properly: I’m not young any more, it’s too late for me to learn new ways. Ksenia agreed and, of course, now he called her nothing but Ksenichka. Since then she had seen over and over again in business negotiations how Pasha extorted advantageous conditions while emphasizing that he had absolutely no right to them and was only asking as a personal favor. Maybe, if Pasha was not coping well with his business, it wouldn’t work – but when it came to PR support and advertising promotion, he was the best there was, and the clients let him have his way.

“How’re things, Ksenichka?”

“Fine, thanks.”

“Fine?” Pasha repeats, turning his monitor toward Ksenia. “Let’s just take a look at our rating. Look, this is Rambler – and what spot are we on?”

A screen with light-blue strips running across it. The Rambler Top 100 Ratings – the most important rating on the Russian internet, the unofficial table of ranks, a kind of independent audit. With meters set up on almost every site in the Russian internet, measuring the traffic. Ever half hour Rambler generates new ratings of sites according to about fifty subject categories. Whoever gets the most hits has the highest rating. Of course, everyone knows that this rating can be hyped up but even so, the advertisers take their bearings from it, and the small investors use it to decide if their money’s working hard enough.

The liquid crystal display of Pasha’s monitor shows the “Media and Periodicals” section. As usual, Tickertape and News.ru are fighting for first place, while Evening.ru is in the doldrums somewhere between ten and twenty.

“What do you expect, Pasha?” says Ksenia. “That’s what comes of being tight-fisted. You know yourself that within the limits of the present budget I do the impossible.”

Her face turns even more stubborn, her lips squeeze together angrily.

“Ksenichka, darling,” Pasha replies, sitting on the edge of the desk, “how can you call it being tight-fisted? Look, in the last year I’ve raised your salary twice. Sure, the first time was when I put you in charge instead of Lena, but the second time was simply because you deserved it, and that’s all. But you tell me, have you started working any better since then? Or, rather, will you start working any better if I give you another two hundred dollars?”

“If I say yes,” says Ksenia, “you’ll say I’m not putting in enough effort, so I don’t deserve a pay rise, if I say no–”

“Then I won’t give you a raise anyway,” Pasha says with a nod. “You understand the whole thing. Every employee has a natural limit: after that, no matter how much you raise their pay, you won’t get anything more out of them. Now, if you came up with some special kind of project – one that generated lots of advertising and lots of traffic! – then I’d give you a separate budget. And, of course, part of that budget would go toward a raise for you. But sorry, I won’t give you any money just like that.”

“What kind of project would you like to have?” Ksenia asks with a smile.

“I don’t know,” Pasha answers with a shrug. “Something that would fit into the concept of our publication and also attract readers. And wouldn’t be like what our friends in the other internet media have.”

I get it, Ksenia thinks with a nod. Magical fairytale stuff – I don’t know what it is, but bring me it.

“I’ll think about it,” she says, getting up.

“You have to understand my position,” Pasha says apologetically. “I haven’t got a lot of money, the election advertising didn’t come up to expectations… well, not entirely up to expectations.”

“I sympathize,” Ksenia says morosely, and for a moment Pasha remembers that he is lying shamelessly: business is going well and there’s plenty of money, but that’s no reason to start giving it away to the staff. Because if someone works for seven hundred and fifty dollars, there’s no point in giving them a thousand. At least, not until someone else starts trying to poach them. And so before every conversation about a raise, Pasha tells himself “there’s no money, there’s no money, there’s no money” until he starts to believe it – and then he can repeat these words with a clear conscience. In the unreal world that he inhabits, it’s the only way.

Ksenia has only a vague idea about all this. But even so, she goes back to her desk feeling quite satisfied: now at least she knows what to do. She just has to come up with some project, then go back to Pasha and start the conversation by saying: “Remember, you promised me…”

She doesn’t take offence at his obvious lies about the election campaign money: deep in her heart Ksenia suspects that if she were in Pasha’s place, she would act the same way. She enjoys observing her boss: he is far from stupid and there are things she can learn from him. Her colleagues sometimes complain that they’re pissed off with Pasha, that he’s so mean. They might be pissed off with him, and he might be pissed off with them, but who else do we have apart from Pasha? she asks herself. A good boss who’s sociable without fraternizing too much and is friendly without any harassment.

Before joining Pasha’s Evening.ru Ksenia used to work as a journalist in the internet section of the Moscow branch of a Western publishing house. Almost all the employees were local, but the office was still dominated by an extreme spirit of American political correctness: a strict dress code, no jokes about sex, no flirting. Her friend Marina, who dropped in occasionally, used to joke that the tea in the plastic cups was about to freeze solid in the positively benevolent atmosphere of the place, but at the beginning Ksenia had actually liked the atmosphere there. Coming to work with her nipples still itching after the clamps and fresh bruises on her thighs, she used to smile to herself and think complacently that her colleagues would recoil in horror if they only knew how she spent the nights. Ksenia had good career prospects, with a chance of moving from the internet department to the advertising department, and she was already mulling over this option. From the age of nineteen, when almost by accident she had found herself as an assistant in one of the laboratories of the Central Institute of Economics and Mathematics, she had always been involved in the web, and sometimes it seemed to her that real life and real business were not here, but out in the real world. But all that came to an end rather sooner than expected, at the out-of-house pre-Christmas party.

They rented a guesthouse outside Moscow. Some people were thinking of going back to the city, but most were intending to stay overnight. The table was laid in the banqueting hall, the Big Boss proposed a toast in fairly decent Russian, the local DJ turned on the strobe lights, the Euro-pop started playing – and an hour later, as she watched her colleagues hopping about friskily, Ksenia was reminded of the old school dances. She liked to dance and she was good at it, but this mawkish oompah-oompah didn’t inspire her. When she was a bit younger, she used to bring her favourite CDs with her – but this wasn’t the right occasion for that. She shrank back against the wall and exchanged a couple of words with Liza from the marketing department, who was wearing an unusually short skirt and was already slightly drunk, and then she went to the table to pour herself a punch. When she leaned over, someone’s hand gave her buttock a gentle squeeze. Two fingers landed precisely on a fresh mark, a long diagonal bluish-black stripe, but that wasn’t important – before Ksenia even realized what she was doing, she swung round and struck out.

Fifteen years earlier, when karate emerged from the underground, her parents had immediately sent her brother Lyova to a club. Lyova had practiced his blows on his little sister and tried to teach her a couple of katas and mawashis. Ksenia was a bad student and she thought she’d forgotten everything in the years since then, but her body’s memory proved very retentive: her blow landed with perfect precision.

Something squelched under Ksenia’s fingers and she was amazed to see blood spreading across the white shirt of the deputy director, ruddy-faced thirty-five-year-old Dima. He had started off as a Komsomol businessman, but come off the road on the steep curve of the 1990s and ended up as a common-or-garden executive, or, to use the modern term, a manager. Now he was on his way up: if you didn’t count the Big Boss, Dima was the third most important person in the whole office. Fortune seemed to be smiling on him again, and perhaps that was why he didn’t move aside and pretend nothing had happened, but tried to hit Ksenia back, and she saw her own right hand move in a slow-motion movie sequence to deflect the blow, and her left hand swing and jab once again into that astonished pink-and-red face.

Afterward, as she tried to thumb a lift on the snow-covered highway and rubbed the stinging knuckles of her fingers with the bitten nails, Ksenia blamed herself and wondered: Did I break his nose or just split it? Yes, Lyova would have been delighted with her, but Ksenia felt ashamed anyway. Good girls didn’t behave like that, and neither did bad ones. Maybe he had touched her by accident, and she had just struck out without bothering to check? Ksenia felt so upset she could have cried – but she never cried. When she got home, she rang her lover at the time and asked him to come over and be rougher than usual: maybe so that the drops of blood would take the place of her uncried tears.

After the holidays she gave in her notice: not even because of that guilty feeling she’d had, and certainly not because she was afraid of revenge. In a single instant Dima had suddenly ceased to be a boss for her. It wasn’t the harassment, it was just that Ksenia couldn’t respect a man who had let through two of her amateurish blows in a row.

But she’s sure of Pasha. He doesn’t confuse the office with the bedroom, and if anything did happen, he’d catch her hand. Or hit her himself.

And anyway, Pasha avoids direct conflicts. He knows nothing about Ksenia’s sexual preferences, but he understands her very well – far better than many of her lovers.

* * *

It was like this: the two of you were in a large group of people you didn’t know very well, some friends of Sasha’s, at the birthday party of one of the girls from his class at school, someone he used to be in love with. Sasha called to collect you, and before you went to the party you made love, never suspecting that it was the last time. At the party people started talking about sex, and you couldn’t resist saying that you liked rough sex, BDSM, to be exact, also known as “playing”: what do you mean, you don’t know what that is? Well, it has a triple meaning: BD is bondage/discipline; DS is domination/submission; and, well, SM is sadomasochism, that’s obvious. In principle, these are all different things: some people who play like bondage, others like submission, and some just like pain for its own sake, but sometimes someone likes all of them together, although I’m pretty much indifferent to bondage. Everybody stopped talking, as if they were embarrassed, and Sasha said something like “That’s too much for vanilla people like us to understand. I never thought you were such a pervert.” You immediately tensed up. Although, of course, that was his right, if he wanted, he could stay in the closet, as the fraternal fags put it, let him pretend to be a decent, vanilla individual, if he felt so ashamed in front of his friends. You got up and walked into the kitchen. Sasha followed you. “Get on your knees and take me in your mouth,” he said, and you flew into a rage. You never promised to submit to him anywhere except in the bedroom, no 24/7, and you had no intention of sucking him off in the kitchen at a birthday party for an old classmate he used to be in love with when he was a delicate little boy and no doubt incapable of beating a girl so hard with a riding crop that the marks on her buttocks took a week to heal. “I don’t want to,” you said and then, remembering your games, he tried to grab you by the hair and force your head down, and then you said it again, feeling yourself getting angrier and angrier: “Don’t,” and he said: “If you don’t do it right now, it’s over.” And then you pushed him away and said: “Then it’s over.”

“If you don’t do it right now, it’s over.” That was the last straw. Not the vanilla public image, not the demand to suck him off. No, it was those nine pitiful words that decided everything. Sasha could have tried to break your will and force you down on your knees (oh, how glad you would have been to suck him off then!) or retreated smoothly, pretending it was all just a joke. You would both have forgotten about it, and the next time at your place you would have been his submissive slave again, but those words – if you don’t do it right now – those words meant he lacked the strength of will to be a genuine master, and he lacked the wisdom to realize it. A pitiful attempt at blackmail, a little boy moaning and telling his mother: “If you don’t buy me that railway engine, it means you don’t love me anymore.” So it means I don’t love him, you thought, and that was the most terrible thing, because the words – the ones he said and your reply – couldn’t be taken back now. You couldn’t pretend they were never spoken. That evening you deleted him from your ICQ and put his telephone number on your Motorola’s blacklist.

Moscow is a small town, you’re bound to meet again – but never again will you lie on the floor in front of him, with your hands tied above your head and your eyes closed so that you can’t see which breast will take the next blow from the double length of telephone wire.

4

AFTERNOON, AND THE CARS ARE ALREADY BUMPER to bumper. The creeping afternoon traffic jam. Bolshaya Nikitskaya Street looks like a river covered with drift-ice in spring. Olya, that is, formally, Olga Krushevnitskaya, a successful businesswoman of thirty-five, an IT manager and co-owner of a small online shop, maneuvers in her Toyota, cursing through her teeth. On her way to have coffee with her friend, she repeats to herself: “So, what was it he said? I wouldn’t even shit in the same field. Just slammed the door and walked out. And what am I supposed to do now? No point in complaining – they warned me: Olya, you’ll come unstuck with these two, there’ll be hell to pay.”

Three years earlier Olya herself invited Grisha and Kostya (that is, Grigorii and Konstantin) to join her business. Or rather, the business wasn’t hers then: Olya was a hired manager on a salary, and she only managed to grab herself a quarter of the business when the shop was bought from the first owners – who, by the way, got three dollars for every one they had put in. That was the way they set up the shares: money from Grisha and Kostya, and from her – knowledge of the market and experience, three years of hard graft. But at the very beginning of the whole thing, someone at the Internet Business Club told her: those two bears will never get along together in your little den.

They won’t get along together in my den. Won’t shit in the same field. They’ll take their money – then it’s goodbye and farewell to Olya’s business. Wolves. Bears. She’d served them faithfully for three years, fed them with her own flesh and blood, interest on profit, flattery and lies. You know how much I like working with you, Grisha. Believe me Kostya, in our business everything depends on you.

Our business? But that wasn’t right. Olya had always thought of the business as hers alone. She had started it and kept it going for all these years, she was the only one who had the vision and understood the development plans, who could anticipate the future. But she had honestly torn chunks off to feed the wolves, trying to forget that wolves were always looking back to the forest. She had held out for three whole years, and now Grisha and Kostya were both bolting from the common field, back into their homeland in the depths of the forest to look for Little Red Riding Hoods – or anyone else they could find to gobble up.

Olya stops at a traffic light, pulls down the mirror and looks at herself. A well-groomed thirty-five-year-old woman. An elegant arm lying on the steering wheel with a bracelet of dark stones round the wrist. A prosperous businesswoman, the co-owner and general director of a small internet shop. No, she didn’t look a bit like Little Red Riding Hood, it wasn’t so easy to gobble her up. She knew every bush in this forest too – and she wouldn’t go to her granny’s little house, she’d go into the dragon’s cave, then we’d see which of the wolves would risk following her in.

And there’s the first miracle of this lousy day: a silver BMW pulls away from the curb at just the right moment – and Olya parks her Toyota. She jumps out on to the pavement, trying not to step in the dirty puddle of melt water, slams the black, mud-splattered door shut, presses the button on her remote and, just as she’s walking into the Coffee House, she hears the quiet beep of the security system. That means everything’s all right. Now she’ll try to choose a table by the window and on the way take a moment to check that everything really is all right. When you live on your own for a long time, you get used to things: to the laptop that should have been changed ages ago, to the bracelet that you were given, hanging round your wrist, to the car that you ought to sell, but can’t bring yourself to. You don’t admit it to anyone except yourself, but you feel a kind of inner kinship with it. Six years for a car is like thirty-five for a woman: still running, but with the price tag falling faster every year. And so you look after it as if it were your own body – regular services, fresh oil, BP gasoline, comprehensive insurance. And there’s the result: great condition, not a single scratch, as good as new.

Her friend Ksenia, who she calls Ksyusha, is already sitting at a table, toying with a cell phone in a kitschy bright-pink fluffy case.

“Look what I’ve bought,” she says. “Isn’t it just delightful?”

Olya politely takes the mobile in her manicured hands and buries her fingers in the pink fur.

“It reminds me of something,” she says.

“Aha,” Ksyusha agrees, “my rabbit, remember, I showed it to you?”

Yes, the pink rabbit. Every over-aged Little Red Hiding Hood should have her own pink rabbit: that way there’s something to give the Big Bad Wolf when he comes knocking at the door of the hut. But Olya doesn’t have any fluffy toys, and you can’t put a case on a Sony-Ericsson P800. All she has is an aging Toyota, well-preserved, but already doomed.

“I was thinking,” says Ksyusha, “if you crossed a cell phone and a rabbit, what would their children be like?”

“Well, fluffy little mechanical devices,” Olya replies. “Like the rabbits in the Energizer advert.”

Little rabbit girls hop around in the dark forests of Russian business and shudder at the roaring of the big bad wolves who can’t share the same field, only the same forest. Because in the field there’s no one to eat, but in the forest there are fluffy pink animals and aging Little Red Riding Hoods who aren’t mobile enough to avoid the wolves’ teeth.

“You’ve got everything mixed up.” says Ksyusha. “A cell phone isn’t a mechanical device, it’s a communications device. They’d probably be telepathic rabbits.”

“There was some story about telepathic rabbits,” says Olya, “remember?”

“Na-ah,” says Ksyusha, “I haven’t read very much. I mean, not as much as you.”

That’s probably a good thing, not to read so much, Olya thinks. She spent almost thirty years stuck in the gingerbread house of their library at home and Petersburg University’s castle in the air. Probably it really is a good thing not to fritter away your time on books, not to know every word of Brodsky’s To Urania and A Part of Speech, smuggled into the country by other lovers of poetry like yourself, but to find yourself out in the dark forest right away, before you got midway through life. To find yourself there without even being able to recognize the hidden quotation (at least one) in that last phrase, but not to feel daunted when you met the wolves, panthers and lions – or whoever it is that Dante and successful IT managers ran into along their way.

“So what happened to the telepathic rabbits in the story?” Ksyusha asks.

“I don’t remember,” Olya replies. “I think they’ve all been eaten before the story even starts. Before anyone has even realized that they are telepaths.”

“Bang-bang, aye-aye-aye, see my little rabbit die,” says Ksyusha, citing the old children’s song. And she knocks her cell phone over as if it has been hit by a hunter’s bullet.

Olya smiles, and her lips cramp at the memory of two wolves glaring at each other from behind the trees in the dense forest of their joint business.

“Listen, Ksyusha,” she says, “I need your help. Will you help me?”

Ksyusha suddenly turns serious – a businesswoman, IT manager, senior editor in the news department of a popular online newspaper – she sets her thin elbows on the table and leans her head to one side, as if to say: I’m listening, come on Olya, tell me what’s bothering you.

And Olya tells her.

Three years ago, at the height of the investment boom, two major internet companies decided to invest in the shop that Olya managed. They bought it from the first owners, gave Olya her twenty-five percent, and divided up the rest between them. Two major companies? Actually just two investors, two men who had known each other since before the internet. Kostya and Grisha, Konstantin and Grigorii. Friends and competitors, rivals and comrades. For three years their furious skirmishes didn’t interfere with the business; it remained a joint interest, until this December when they quarreled big-time over dividing up the funds from the election campaign. And this morning Grigorii slammed the door of Olya’s office and shouted “I wouldn’t even shit in the same field.” The little online shop – a rather trivial business by Kostya’s and Grisha’s standards – turned out to be the little goat from that other children’s song that took it into its head to go wandering into Dante’s dark forest at just the wrong time. The situation was tragic in an entirely literal sense – Olya’s business was about to sing its farewell goat song and become a ritual sacrifice in a squabble between two former friends.

She can repeat the old familiar move and bring in a big new investor to buy the business from Grisha and Kostya. There isn’t anyone like that in the Russian internet – but Olya knows who she could go to. If, that is, she can really take the risk of going to him – because Olya doesn’t like this man. He’s an outsider, someone from a different and dangerous world, from offline, ordinary business, business that makes Kostya’s and Grisha’s wild, remote forest look like a tidy English park.

Olya explains all of this to Ksyusha now, explains it carefully, trying to avoid any allusions to Dante, jokes about the little gray goat and goat song – because she’s not sure that Ksyusha knows about scapegoats, Dionysian sacrifices and the birth of tragedy out of the spirit of music. After all, Ksyusha didn’t graduate from the history faculty in Petersburg; immediately after school she set out like an emancipated Little Red Riding Hood along the winding path to a place where there had never been any granny, but there was at least some faint hope of earning your own piece of bread and butter.

As Olya tells her story, Ksyusha watches the way she waves her hand, and the way the bracelet on her wrist shimmers. Large dark stones, as dark as Olya’s eyes. Olya waves her hand beautifully, she draws beautifully on her long cigarette holder, she talks beautifully and even sighs beautifully. If Ksyusha could fall in love with a woman, she would definitely fall in love with Olya. You might say she has already fallen in love: at the negotiations three years earlier she said “Wow!” to herself the moment she saw this tall woman with the well-groomed hands, short light-tinted hair and deep, dark eyes. They discussed the terms for yet another advertising campaign, and Ksenia thought she wanted to be like Olya someday. Perhaps she simply liked Olya’s way of inclining her head during a conversation, smiling with just the corners of her mouth and waving her hand fluently when she rejected an unacceptable proposal. Ksenia even liked the not exactly old-fashioned, not exactly provincial Petersburg way she smoked a cigarette, drawing in the smoke through a long cigarette holder. On that first occasion they got through the business quickly and spent another forty minutes talking about all sorts of nonsense, she can’t remember exactly what now. They immediately started calling each other “Olya” and “Ksyusha,” and now they meet a couple of times a week, and Ksyusha is glad her premonition didn’t deceive her: it was friendship at first sight.

“And so,” says Olya, stubbing her cigarette out in the ashtray, “I want to ask you to make some inquiries about him, about this man. I don’t really know anything about him, but you’re a journalist, so you can manage it, right?”

5

KSENIA WALKS THROUGH THE PASSAGE FROM ONE subway line to the other in a dense crowd of people, in a vortex of deep human waters, a subterranean reflection of the traffic jams on the Moscow streets. Instead of frosty Tverskaya Street with its smell of petrol, there is the stale air of Pushkinskaya Station; instead of the stench of tobacco in the front seat of a private car acting as a taxi, there is the smell of sweat in the stuffy carriage. Save fifteen, no, twenty minutes and two hundred, no, one hundred and fifty rubles, get there for seven as she promised, not be late at least this once.

She was never late for business meetings or assignations, but somehow she had never managed to get to her mother’s place on time, ever since she was a child, when it used to take her an hour to get home from school, stopping for a chat with Vika, and then with Marina, who she called Marinka, saying goodbye ten times on every corner, and then deciding to make a detour anyway, walking to the garages first, and then to the bus stop. It took her fifteen minutes to walk to school and an hour to walk back. She had to be at the dance studio by three. Ksenia didn’t really have to hurry, but her mom was nervous anyway, she said she would go crazy, times weren’t what they used to be, now they didn’t even let little children go to school on their own, let alone Ksenia, a beautiful ten-year-old girl, the delight of any pedophile, a future Lolita, the light of her parents’ lives, the fire of God only knew whose appalling loins. Ksenia was stubborn, she forbade her mother to meet her, swore she would come home on time, but she still came late. Her mom made a show of drinking her decoction of one-hundred-percent natural valerian from virgin forests somewhere in Siberia or the Urals, her mom clutched at her heart, her mom said her daughter didn’t love her at all. Ksenia persuaded herself that these reproaches were a proof of love. Not of her love for her mom, of course, but of her mom’s love for her. Because if her mom didn’t love her, why would her mom get so anxious?

Lyova was already in eleventh grade at school and he was regarded as quite grown up already, he had even applied for a place in college amid a general atmosphere of approving indifference: who could ever doubt it, of course he would get in. Ksenia heard Lyova telling a friend or a girlfriend on the phone that if not for the army he would never have applied for college; who needed an education now? And he probably wouldn’t be a physicist, there was no money in it, unless you went away to America. Afterward, many years later, Ksenia was surprised at how much he knew about everything in advance: he had been right twice over – he didn’t become a physicist and he went away to America.

She was always home late from school; only once, when half the class, including Vika and Marinka, was off sick with flu, she came on time and ran into Slava in the entrance of the building (he was the one, by the way, who never wanted to be called “uncle” – just Slava, that was all) and he hesitated, as if he was embarrassed about something, mumbled “Hi” and hurried off to the bus stop. She walked in, shouted “Mom, I’m home!” and through the half-open door of her parents’ bedroom she saw the crumpled sheets and didn’t understand at first, then her mom came out of the bathroom wearing a robe over her naked body, with her hair all clumped together. “What are you doing here so early? You could at least have rung the doorbell.” She’d never asked Ksenia to ring the bell before, Ksenia had had her own keys since third grade, and now as she stood there in the corridor Ksenia started blushing uncontrollably, as if she’d done something unforgivable, almost criminal. She whispered, “Sorry, Mom, I didn’t think,” and went to her room, trying not to look round at the grinning door of the bedroom and burning with shame, feeling like a criminal for having found out something she wasn’t supposed to know. The latest number of Mom’s AIDS-Info, the sex education tabloid, was lying on the floor beside her bed, she’d been reading it yesterday before she went to sleep, she was proud that her mom and dad weren’t like other girls’ parents, they didn’t hide anything, on the contrary, to her grannies’ horror, they had explained everything to her at the age of six with a little book translated from French, so that now, at the age of ten, Ksenia knew absolutely everything about that. But today this pride and this joy had disappeared somewhere. Ksenia felt ashamed. She would rather not have known what had been going on only half an hour earlier in her mom’s bedroom. It would have been better if she didn’t read AIDS-Info, but read what all the girls did, something like Alexandra Ripley’s continuation of Gone With the Wind. She wanted to cry, but she’d forbidden herself to do that, big girls didn’t cry. Ksenia never cried, and anyway, what point was there in crying, tears wouldn’t help her grief, her mom was right, it was Ksenia’s own fault, she shouldn’t have come back at the wrong time, if she was so grown-up already and understood everything so well. And so Ksenia sits there in her room, takes the textbooks out of her briefcase and starts doing her homework. Mom always said: if you feel like crying, go and do your lessons. Especially since she has a test tomorrow, and she has to get an A.

Ksenia walks through the passage under the stone vaulting of the Stalinist subway system. There are little wind-up khaki-colored soldiers crawling along the wall, with their machine guns chattering, but the toy guns can barely even be heard above the noise of the crowd. The soldiers crawl along as if they are delirious, with their entire bodies squirming, squirming as if they are dodging blows, as if in erotic ecstasy, crawling as if their legs refuse to carry them, crawling to some unknown destination, invalids continuing a futile war, a war that was over long ago. They will survive and ride through the carriages in the underground in metal wheelchairs, collecting money in paratroopers’ berets, crippled, with no legs, either drunk or stoned. Ksenia will lower her eyes into her book, trying not to look at them, trying not to remember how every time she encounters pain, suffering and physical deformity, people who have lost arms or legs, it is like some kind of prediction that could affect her personally. The same way she used to feel frightened by articles about psychotic killers, sadists and perverts who tortured their partners by hanging them from a hook in the ceiling by their outstretched arms, covering their bodies with the parallel stripes of scars, welts and bruises. It’s still there, that aching pain of separation, now what have you done, where are you going to find another lover like that? But it’s over – don’t you understand that? It’s over.

Ksenia walks through the passage. Clattering heels, dark business suit, short winter coat. One thin hand lightly holding the purse in place on her shoulder. Walking through the passage. Twenty-three years old, a good job, excellent prospects. Walking through the passage.