6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Open Book Publishers

- Sprache: Englisch

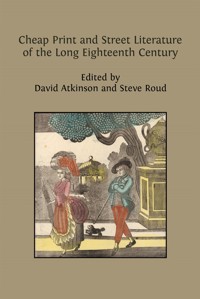

This deeply researched collection offers a comprehensive introduction to the eighteenth-century trade in street literature – ballads, chapbooks, and popular prints – in England and Scotland. Offering detailed studies of a selection of the printers, types of publication, and places of publication that constituted the cheap and popular print trade during the period, these essays delve into ballads, slip songs, story books, pictures, and more to push back against neat divisions between low and high culture, or popular and high literature.

The breadth and depth of the contributions give a much fuller and more nuanced picture of what was being widely published and read during this period than has previously been available. It will be of great value to scholars and students of eighteenth-century popular culture and literature, print history and the book trade, ballad and folk studies, children’s literature, and social history.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

CHEAP PRINT AND STREET LITERATURE OF THE LONG EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

Cheap Print and Street Literature of the Long Eighteenth Century

Edited by David Atkinson and Steve Roud

https://www.openbookpublishers.com

©2023 David Atkinson and Steve Roud (eds). Copyright of individual chapters is maintained by the chapters’ authors.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for non-commercial purposes, providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). The majority of the chapters in this volume are licensed under the CC BY-NC license and if published separately follow that attribution. License information is appended on the first page of each contribution.

Attribution to the volume should include the following information:

David Atkinson and Steve Roud (eds), Cheap Print and Street Literature of the Long Eighteenth Century. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2023, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0347

Further details about CC BY-NC-ND licenses are available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web.

Copyright and permissions for the reuse of many of the images included in this publication differ from the above. This information is provided in the captions and in the list of illustrations. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher.

Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0347#resources.

ISBN Paperback: 978-1-80511-039-2

ISBN Hardback: 978-1-80511-040-8

ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-80511-041-5

ISBN Digital ebook (EPUB): 978-1-80511-042-2

ISBN XML: 978-1-80511-044-6

ISBN HTML: 978-1-80511-045-3

DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0347

Cover image: ‘Jack on a cruise’, pewter print. British Museum 2011.7084.20, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jack_on_a_cruise_(BM_2011,7084.20).jpg

Cover design: Jeevanjot Kaur Nagpal

Contents

List of Abbreviations vii

1. Introduction 1

David Atkinson and Steve Roud

2. Charles and Sarah Bates and the Transition from Black-Letter 27

David Atkinson

3. Pictures on the Street: Cheap Pictorial Prints in Eighteenth-Century Britain 53

Sheila O’Connell

4. Popular Print in a Regional Capital: Street Literature and Public Controversy in Norwich, 1701–1800 77

David Stoker

5. Anthony Soulby, Chapbook Printer of Penrith (1740–1816) 113

Barry McKay

6. Chapmen’s Books Printed for Henry Woodgate and Samuel Brooks (1757–61) 137

David Atkinson

7. Slip Songs and Engraved Song Sheets 165

David Stoker

8. ‘The Arethusa’: Slip Songs and the Mainstream Canon 195

Oskar Cox Jensen

9. Story Books, Godly Books, Ballads, and Song Books: The Chapbook in Scotland, 1740–1820 219

Iain Beavan

10. Alphabet Pies, Animal Quacks, and Ugly Sisters: John Evans and the Growth of Cheap Books for Children 259

Jonathan Cooper

11. Street Literature and Cheap Fiction 321

David Atkinson

12. Afterword 347

Select Bibliography 355

Index 373

1. Introduction

© 2023 David Atkinson & Steve Roud, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0347.01

David Atkinson and Steve Roud

It would not be entirely fair to claim that the street literature of the eighteenth century has been totally ignored, but only recently has increased online access to original materials helped open up interest in a period that has been overlooked in comparison with, say, the early modern period or the nineteenth century. It is a premise of this collection of case studies that, in fact, the eighteenth century represents a critical period both of continuity and of transition between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. The essays themselves begin with the period around the lapse of the Printing Act in 1695, which opened the way for printing outside of London, and also saw the transition from the use of black-letter to white-letter typefaces for items of cheap print. They then extend through to the end of the wooden hand-press period, in the first couple of decades of the nineteenth century. At that time, the change to machine-made paper brought lower costs and improved quality, the iron hand-press enabled better-quality copies to be printed at a faster rate, and the introduction of stereotyping made reprinting possible without the need either to reset type or to retain standing type. All the same, printers at the cheap end of the trade were prone to using older or second-hand technology, so, ground-breaking as these changes were, they did not come all at once. In this perspective, the period covered in this volume can usefully be described as ‘the long eighteenth century’.

The other important premise is that ‘street literature’ encompasses, in principle, anything that was cheap to print and cheap to sell. To an extent — albeit not completely — ‘street literature’ and ‘cheap print’ can be considered interchangeable terms. In practice, the major street literature genres include broadside ballads and songs, prose and verse chapbooks, short sermons and devotional works, almanacs, and pictorial prints. Some other cheap printed items, such as handbills (which were typically distributed gratis), and things that were genuinely ephemeral (such as lottery tickets), can usefully be excluded. Nevertheless, it is still very difficult to impose a definition, because there are several different ways of considering the material: from the perspectives of format and typography, cost and mode of sale, readership and audience, subject and theme, genre and literary history — or, more broadly, production, distribution, and reception. This was the lower end of the print trade and market, in terms of price, technology, skills, and textual and visual content, even if some of those parameters turn out to be rather porous. For example, while an established London bookseller could issue the occasional ballad or chapbook in between the production of books for a more sophisticated market, it was still much more difficult for a local printer — most of whose work would have been jobbing printing, which did not require substantial up-front investment in technology, personnel, and materials — to branch out into book production.1 This divide within the print trade itself offers one useful way of distinguishing street literature from what we tend to think of as mainstream bookselling.

In that light, what is offered here is a selection of essays by scholars specializing in the street literature of the eighteenth century, on subjects of their own choice, reflecting their own research interests. It is too soon to attempt anything like an overarching history of the field, which will only eventually emerge from a cumulative picture built up from micro-studies of the kind presented here. In the meantime, it has seemed important to make a start. The individual chapters can be read as stand-alone pieces, but are arranged in a roughly chronological order, which will provide some sense of the continuities and developments across the long century. It is something of a convention that editors of collections like this summarize their contributors’ chapters, but in this instance we believe the scholars should be allowed to speak for themselves. Instead, an ‘Afterword’ will endeavour to draw out some of the major themes and questions raised by the essays — not so much in the form of conclusions, but as a way of pointing out directions for further research. The remainder of this ‘Introduction’ is divided into sections that outline some of the areas that have exercised researchers to date: popular culture and the question of literacy; the growth of the trade in London and the regions; the itinerant trade, chapbooks and chapmen; the matter of street literature; and the scale of the trade in street literature.

Cheap print, literacy, and popular culture

The term ‘street literature’ tends to imply printed matter that was sold by itinerant sellers — variously described as chapmen, pedlars, or hawkers — who might either specialize in printed items or alternatively sell a wide range of portable goods in urban streets, at markets and fairs, and even door-to-door. Pedlars were omnipresent across late medieval, early modern, and eighteenth-century Europe.2 For England, there is more detailed evidence about chapmen at large for the previous century, thanks to the ground-breaking work of Margaret Spufford.3 Street ballad sellers, however, are particularly well documented in newspapers and sometimes in criminal proceedings of the eighteenth century.4 The itinerant print trade underpins much of our understanding of street literature in eighteenth-century Britain, but it is not a single defining characteristic. Numerous imprints indicate that titles could also be bought directly, wholesale or retail, from the printers’ premises, booksellers, stationers, and other retail outlets that sold cheap goods, especially in urban centres. The second half of the century saw a considerable expansion of bookselling in provincial towns.5 The radical weaver Samuel Bamford, for example, mentions ‘numerous songs, ballads, tales, and other publications’ exhibited in the windows of the Swindells bookshop in Manchester at the end of the century.6

Typographical format is also a useful starting point, and it is not too difficult to identify the major London, provincial, and Scottish printers and booksellers specializing in broadsides and chapbooks, and to take their output as characterizing the trade. Nevertheless, while single-sheet publications are indeed at the heart of the street literature trade, some of the same booksellers issued books that ran to several sheets. Broadsides and 24-page chapbooks that sold for ½d. or 1d. were printed — and therefore presumably sold — in large quantities and can be considered cheap, but the same booksellers sold small books in similar formats at 3d. or 6d., and sometimes even at 1s. Robert D. Hume addresses in detail the question of the affordability of culture and concludes that the books, theatre, concerts, opera, and paintings that are widely studied today comprised an essentially elite culture.7 Street literature, however, rendered culture (in its broadest sense) much more widely accessible than that bleak assessment suggests. Cheap is an ill-defined measure, for affordability would be determined not simply by the cover price but by the entire socio-economic situation of the potential purchaser; while a broadside at 1d. may not have been a trivial purchase for a labourer earning around 10s. per week at the end of the century, others might have found anything up to 1s. affordable on occasion.

Estimating access to print in terms of literacy levels is fraught with potential difficulties, and undoubtedly there were considerable variations correlated with factors such as social status, age, gender, occupation, location (urban vs. rural), religion, and so forth. Nevertheless, to read a broadside ballad or a small chapbook did not necessarily require an advanced level of literacy. Practical, functional literacy was not uncommon even at the beginning of the century, and literacy rates continued to rise from that time, especially for women, leading to a remarkable growth in the size of the reading public by the century’s end.8 In urban environments, the population would have enjoyed considerable exposure to the printed word in the form of advertisements, handbills, proclamations, and things such as lottery tickets and official or commercial forms, as well as to the hawkers selling ballad sheets and other printed matter. The expansion of the book trade, and especially the trade in cheap and readily accessible print, was both an indicator and a driver of this advance of literacy, which was becoming an essential asset of commercial life, especially in towns and cities. Furthermore, even if not everyone could read them for themselves, they would most likely have come into contact with others who could — indeed, songs and stories, perhaps also some devotional works, specifically lent themselves to being read aloud. Accordingly, it is not unreasonable to think of the eighteenth century as a time of widespread exposure to a literature that can be described as ‘popular’ in the general sense of the word.

Used with caution, terms such as ‘popular literature’, ‘popular culture’, or ‘print for the people’ can imply the sort of cut-off point in relation to price suggested above, as well as hinting at a particular kind of subject matter, but ‘popular’ remains an elusive concept.9 At a later date, and with increased mechanization of the printing process, it would come to include things like magazines and fiction of the penny-dreadful kind, which are not pertinent here. Moreover, while the scholarship on street literature tends to exclude things such as political verse satires, it is also the case that the political elite could take an interest in and exploit the potential of, say, the ballad genre. Election ballads and broadsides survive in significant numbers (though perhaps more so from the nineteenth century, and often hidden away in less readily accessible archives) and deserve further investigation.10Sermons and other theological works, which are often typographically akin to verse and prose chapbooks, might have been printed at the author’s expense and never achieved more than limited circulation. On the other hand, Isaac Watts’s Divine Songs were widely reprinted in cheap formats, and at the end of the eighteenth century Hannah More’s Cheap Repository Tracts deliberately copied the familiar forms of street ballads and prose stories. Booksellers, especially in Scotland, listed what we might class as devotional titles or works of popular theology alongside their fictional titles. As another example, several of the legendary tales — titles such as Argalus and Parthenia, Dorastus and Fawnia, The Seven Champions of Christendom — were published in cheap chapbook versions of twenty-four pages but also in books of around half a dozen sheets costing 1s. To be sure, the market was differentiated by price, and the texts differ in degree of sophistication, but fundamentally the stories were the same, and readers could (in principle) graduate to the longer versions.

Cheap print in London and the regions

A convenient beginning is the lapse of the Printing Act in 1695, before which date trade printing had been effectively confined to London. Cheap printing did not immediately take off outside the capital, but the first newspapers were quite rapidly established in Bristol, Exeter, and Norwich. Ballads and prose and verse chapbooks continued to be printed in London by a succession of booksellers, who were often related to one another by familial ties. Ballads were typically half-sheet broadsides, while single-sheet chapbooks at this date were mostly in quarto or octavo. From 1711, John White in Newcastle was publishing the Newcastle Courant, and William Dicey and Robert Raikes established provincial newspapers including the St Ives Mercury, Northampton Mercury, and Gloucester Journal during the period 1719–22. These are significant figures because both White and Dicey also printed ballads and chapbooks, and the link between newspapers and cheap print was no coincidence because the networks established to facilitate the distribution of the former were equally suited to the latter.11

There survive some fifty ballads printed in Northampton by William Dicey, a few of them jointly with Robert Raikes. Roger’s Delight has printed on the verso a satirical print dated 1720, and the imprint gives a good idea of the distribution network.12 There also survive a couple of Raikes and Dicey chapbooks, also dated 1720, priced at 3d. each.13 John White was in business in Newcastle up until 1769 and it is very difficult to ascribe dates to his ballads, which are not infrequently the same titles as those issued by Dicey. At one time it was thought that the Newcastle examples were ‘piracies’.14 However, it now seems more likely that there was some kind of business arrangement, and there survives one ballad with an imprint that links the names of the two booksellers.15

William Dicey maintained the Northampton premises, but his sister Elizabeth married John Cluer, a bookseller in Bow Churchyard in London, and after his death she continued to run the business along with the foreman, Thomas Cobb, before handing it over to her brother in 1736.16 In 1740 William Dicey’s son, Cluer Dicey, took over the running of the Bow Churchyard business. In 1753 the firm acquired a junior partner in the person of Richard Marshall, and in 1754 they opened a second London printing shop in Aldermary Churchyard, of which Marshall became the manager. Soon after William Dicey’s death in 1756, Cluer Dicey moved back to take charge of the Northampton business and began to concentrate on the sale and distribution of patent medicines. Printing continued in Bow Churchyard until 1763, after which the premises were used for the patent medicine business, while the Aldermary Churchyard business continued from c.1770 under the management of Richard Marshall.

The Bow Churchyard and Aldermary Churchyard addresses recur endlessly in ballad and chapbook imprints, and there are many publications without imprint that can be confidently attributed to the Dicey/Marshall firm. Invaluably for researchers, William and Cluer Dicey, and Cluer Dicey and Richard Marshall, issued catalogues in 1754 and 1764, respectively. These list significant numbers of maps, pictorial prints on copper and wood, old ballads, slip songs (too many to list individually), prose and verse chapbooks, patters, broadside carols, and other small books. Because some of the titles are the same as those published by the seventeenth-century ballad partnership, it has been assumed that ownership simply passed down to the Dicey/Marshall firm.17 However, it is not clear whether there really was a direct transfer of ownership, or whether subsequently there was simply little effort made to assert and protect ownership in cheap titles. Although the titles of topical pamphlets were sometimes entered in the Stationers’ Register during the eighteenth century, and in the final decade the titles of many of the Cheap Repository Tracts were entered, there were no more entries of the familiar ballad and chapbook titles after 1712 when Charles Brown and Thomas Norris made a large entry of old ballad and chapbook titles.18

The London trade in the early decades of the century saw a considerable continuity of titles from the previous century, alongside the production of new titles. The Dicey/Marshall firm emerged as the dominant force in the ballad and chapbook market through the middle decades of the century. They specialized in the street literature trade and their prolific output has (quite justifiably) made them into a paradigm for scholars of cheap print. They were never alone, though, and there were many more booksellers who produced printed matter of different kinds in small formats priced at no more than a few pence.

A few examples from the earlier years of the century will have to suffice. Printer and bookseller Henry Hills, who died in 1713, succeeded to his father’s share in the King’s Printing House and printed Acts of Parliament and other government documents, but also sold a variety of titles in small formats up to around forty pages at prices ranging from 1d. to 3d.19 Examples are editions of Dryden’s Eleonora and the satirical writer ‘Ned’ Ward’s Honesty in Distress and Pleasures of the Single Life, all sixteen-page octavos priced at 1d., and a reprint of a sermon preached at Cambridge University in 1693 in a 36-page octavo priced at 3d. According to John Nichols, Hills was ‘a notorious Printer in Black Fryars; who regularly pirated every good Poem or Sermon that was published’.20 At much the same time, Ebenezer Tracy at the Three Bibles on London Bridge published sermons and devotional works at 3d., alongside more substantial volumes such as a collection of Madame d’Aulnoy’s fairy tales at 1s.21

This seems to have been a not uncommon pattern, making it more difficult to draw a clear distinction between booksellers rooted in the cheap print trade and the London trade at large. The aforementioned Charles Brown and Thomas Norris published ballads and chapbooks, and also devotional, medical, and other works of general utility at prices up to 1s. 6d.22Norris died in 1732 and his successor at the Looking Glass on London Bridge was James Hodges, a bookseller of some distinction from the 1730s until c.1758 (when he was knighted by George II), who published many works of fiction, poetry, science, medicine, navigation, practical instruction, theology, history, and also some broadside ballads and chapbooks.23

An obscure bookseller called Joseph Hinson at the Sun and Bible in Giltspur Street was probably the successor to Sarah Bates, who ran the business until c.1735, largely specializing in street literature.24Hinson is known from just two recorded titles, both of which look like cheap print — The Siege of Gaunt, a broadside ballad that dates back to the Restoration period (presumably sold for 1d. or less), and A Gold Chain of Four Links, to Draw Poor Souls to their Desired Habitation, a tract on the subject of dying well and attaining salvation (twenty-four pages duodecimo).25 The last few pages of A Gold Chain of Four Links, though, carry advertisements for chapbooks such as Guy of Warwick (ten sheets, large quarto, stitched, price 6d.), Doctor Faustus (quarto, stitched, price 6d.), Montelion (twenty-two sheets, quarto, stitched, price 1s. or 1s. 6d. bound), fifty-five titles listed at 1s. each, and

all sorts of Bibles, Common Prayer, Testaments, Psalters, Primmers [

sic

], Horn-Books, Bound-History-Books, 3 Sheet Historys, Small penny Histories of all sorts; Parents’ Gifts to their Children, and small penny Bibles, with very great Variety of Ballads and Garlands both Old and New: Likewise Shop-Books, Pocket Books, Slates, Pencils, Wax, Wafers, Pens, Ink, P[a]per of all sorts, Ink-horns, Sand-dishes, and all other sorts of Stationary [

sic

] Ware. Also a very curious Sortment of Royal Sheet Pictures either Black or Coloured, Wooden-Cuts of divers sorts, with a very great choice of Lottery-Pictures for Children, by Wholesale or Retail at reasonable Rates.

The fifty-five titles at 1s. mostly correspond with the lists of what Henry Woodgate and Samuel Brooks in the 1760s specifically called ‘chapmen’s books’ (Hinson did not use that term).26 Advertisements along these sorts of lines are by no means uncommon. The fact that Hinson is virtually unknown now stands as a reminder of just how much cheap print is likely to have been lost to posterity.27

Thomas Bailey began publishing lives of criminals, jest books, religious and instructional titles, and cheap amatory fiction in Leadenhall Street in the 1740s, and the firm’s activities were continued by his family after his death.28 A few years later, Robert Powell and Charles Sympson in Stonecutter Street, and Larkin How in Whitechapel, were printing chapbooks and ballads on a significant scale, and a good number of their publications are extant.29Sympson appears to have started in business as a general bookseller in Chancery Lane in the early 1750s before switching to predominantly (though not exclusively) street literature titles in Stonecutter Street. Another obscure bookseller called Samuel Hobbins, also in Whitechapel around 1750, printed a few ballads and songs as eight-page chapbooks. Another staple of the trade was bellman’s and lamplighter’s verses, single sheets printed for parish officials to distribute at Christmas and New Year in the hope of pecuniary reward, which survive in examples from the late sixteenth until the early twentieth century, well represented by surviving sheets printed by Thomas Bayley in Petticoat Lane from the 1760s onwards.30

Outside of London, besides John White in Newcastle, there were other booksellers publishing ballads and chapbooks before the middle of the century. For example, the first known printer in Sheffield, John Garnet, was in business from 1736 and published a duodecimo song chapbook dated 1745,31 as well as other undated ballads, and some with dates in the 1750s. The second Sheffield printer, Francis Lister, published a broadside ballad on the battle of Culloden in 1746.32 In Gosport, James Philpot(t), active during the period 1708–36, printed Constance and Anthony, a ballad from the Restoration period included in the Brown and Norris list of 1712 and in the 1754 and 1764 catalogues of the Dicey/Marshall firm.33 Dating cheap print is fraught with difficulty, but small numbers of surviving ballads and chapbooks suggest that printers were also at work in towns such as Birmingham, Bristol, Canterbury, Chester, Colchester, Durham, Exeter, Gosport, King’s Lynn, Manchester, Newcastle, Reading, and York during the first half of the century. The small scale of surviving examples suggests both that only certain booksellers really specialized in the cheap print market, and that many a general printer/bookseller at one time or another published or otherwise dealt in a few street literature titles.

It is easier to identify booksellers specializing in the street literature trade in the second half of the century. Samuel Gamidge, for example, was established in Worcester by the mid-1750s, but was bankrupt by 1777.34 Others entered the trade between the 1760s and 1780s, a period that saw considerable expansion of the provincial trade, including John Butler (Worcester), Samuel Harward (Tewkesbury), the Cheney family (Banbury), William Eyres (Warrington), Thomas Saint, successor to John White, and then the Angus family (Newcastle), John Ferraby (Hull), John Fowler (Salisbury), James Grundy and John Grundy (Worcester), Samuel Hazard, who produced religious and moralistic ballads (Bath), Joseph Smart (Wolverhampton), the Swindells family (Manchester), John Turner (Coventry), Stephen White (Norwich), John Dunn (Whitehaven), Ann Bell, and Anthony Soulby (Penrith), and lesser-known figures such as John Pytt (Gloucester), Mary Rose and John Drury (Lincoln), John Pile (Norton, near Taunton), and Joseph Bence (Wotton-under-Edge).35 In London, probably commencing in the 1770s, Thomas Sabine in Shoe Lane published chapbooks (but not ballads), alongside cheap fiction, cheap playbooks, and works of practical instruction.36

Many of these booksellers are best known for street literature, jobbing work, and so forth, but some of them still engaged more widely in the book trade. Samuel Harward published ballads and song chapbooks in Tewkesbury, but also conducted business as a general bookseller in Cheltenham and Gloucester, and eventually became a leading citizen in Cheltenham, although by that time it appears he had probably left the street literature trade behind.37 William Eyres was a major figure in the book trade, publisher to the Warrington Academy, who also issued almost fifty surviving song chapbooks.38 John Cheney founded a printing and bookselling dynasty in Banbury, a town that (like Tewkesbury) was an important hub on the eighteenth-century road network.39 John Feather observes that London printers alone simply could not keep up with demand from outside the capital.40

When Richard Marshall became the sole proprietor of the Aldermary Churchyard business it diversified into the developing genre of cheap literature aimed specifically at children, which booksellers such as John Newbery had pioneered from the 1740s. Prior to that time, it is thought that children would have read, or had read to them, the same cheap chapbook stories as were enjoyed by adults. The business continued in the hands of the Marshall family until the end of the century, notwithstanding an extended legal dispute between John Marshall and their erstwhile manager John Evans.41 In 1795 John Marshall became one of the printers, along with Samuel Hazard in Bath, of Hannah More’s Cheap Repository Tracts, ballads and chapbooks that mimicked the mainstream street literature but carried a strongly religious and moral message. The following year, editions were printed both on better-quality paper to be sold at 1s. 6d. per two dozen to the gentry (for them to give away), and also on coarser paper to be sold to hawkers at 6d. per two dozen, allowing them to make a decent profit when the tracts were sold at 1d. each.42 At the same time, having fallen out with Marshall, John Evans continued to develop a genre of literature specifically aimed at children.43

In Scotland in the eighteenth century, broadside and chapbook printing was initially largely confined to Edinburgh, followed later by printers in Glasgow and Aberdeen, with some ballads and the like also imported from England.44 Before the 1770s, examples survive in much smaller quantities than is the case for England, but the last decades of the century saw a huge expansion, giving rise to what has been called the heyday of the Scottish chapbook, which lasted for around half a century.45 Important figures in the development of the Scottish cheap print trade include Robert Drummond, Alexander Robertson, James Robertson, and John Morren in Edinburgh, the Robertson family and Robert Hutchinson in Glasgow, James Chalmers III in Aberdeen, Daniel Reid, Patrick Mair, and Thomas Johnston in Falkirk, and Charles Randall, Mary Randall, and William Macnie in Stirling, with others entering the trade after the beginning of the new century.

Compared with England, the Scottish trade in cheap print was slower to become established, but lasted longer. Among the factors influencing the Scottish pattern were censorship by church and state during the earlier period, and the more rural nature of the population in the later period. In England, John Pitts and James Catnach entered the trade right at the beginning of the nineteenth century. They and their successors would become the dominant broadside printers in London, while others would print similar items elsewhere in England, until the broadside trade was eventually eclipsed by the rise of penny newspapers and other kinds of cheap books, including songbooks. In Scotland, the Poet’s Box operations in Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Dundee were issuing large numbers of broadsides during the mid-nineteenth century, while chapbooks were still being printed in places such as Aberdeen towards the end of the century.

Chapbooks and chapmen

Itinerant sales do not define street literature, which could also be purchased directly from the printers or from bookshops, but sellers at markets and fairs, in the streets, and from door to door, were visible throughout the period. Indeed, the Oxford English Dictionary defines a ‘chapbook’ as a ‘modern name applied by book-collectors and others to specimens of the popular literature which was formerly circulated by itinerant dealers or chapmen, consisting chiefly of small pamphlets of popular tales, ballads, tracts, etc.’ (with a first citation from 1824).46 Recent research, however, has found eighteenth-century instances of the term, which may have simply arisen as a contraction of ‘chapmen’s book’.47

Some bibliographers prefer a more precise definition: of a small book comprising a single sheet printed on both sides and folded, which would usually be between eight and thirty-two pages.48 Others, however, have been content to include under the term any sort of book that was, or might have been, carried and sold by a chapman.49 That would permit the inclusion of things like Robin Hood’s Garland, which contains a collection of Robin Hood ballads (which could also be found for sale individually) and typically runs to around ninety-six pages.50

Matthew Grenby argues for a more nuanced definition which derives from a dynamic relationship between key characteristics of physical format, cheapness, distribution by means of itinerant chapmen, and content of a generally ‘plebeian’ kind.51 Even so, printed catalogues of ‘chapmen’s books’ available from the London bookselling partnership of Henry Woodgate and Samuel Brooks during the period 1757–61 include duodecimos of half a dozen or so sheets, priced at 1s.52 Although distributed by chapmen, they are perhaps unlikely to have been sold in the street or at markets and fairs. Thomas Sabine, too, advertised books at 4d., 6d., and 1s., alongside ‘A large assortment of Penny Histories at 3s. per hundred’ (wholesale), among which were titles dating back to the seventeenth century.

Commonly called ‘chapbook histories’, legendary stories and romances had been published in 24-page chapbook format since the Restoration period. Samuel Pepys formed a collection of ‘small merry books’, and Margaret Spufford thought that chapbook publication became more important to the cartel of London booksellers known as the ballad partnership than the ballads themselves.53 The term ‘chapbook histories’ was a very broad one and embraced, for instance, old stories and legends, new stories and ‘news’, jokes, riddles, and prognostications, practical information and instruction, popular theology, and a few abridgements of popular literary works such as Robinson Crusoe. The formulation ‘histories’, ‘merry books’, and ‘godly books’ covers much of the territory, but will invariably appear to omit something. Many of the titles recur throughout the period in question — titles like Fair Rosamond, Jane Shore, Edward the Black Prince, Thomas Hickathrift, Guy of Warwick, Valentine and Orson, and Aesop’s Fables, for example. By the time of the chapbooks listed in the Dicey/Marshall catalogues the typical format was duodecimo, although earlier examples could be in quarto or octavo.

Songs were also frequently published in chapbooks, particularly collections of songs in small books of eight or twenty-four pages, sometimes known as ‘songsters’ or ‘garlands’ (although this latter term can be confusing because some broadside ballads were also called ‘garlands’). As a crude distinction, the long narrative ballads, some of them dating back to the seventeenth century, were more likely to be printed on broadsides during the first half of the eighteenth century. They are typified by the titles listed as ‘old ballads’ in the Dicey/Marshall catalogues. Indeed, ‘old ballads’ is probably better understood as a way of referring to the half-sheet broadside format than to the content, as only some of them really were old at the mid-century. Chapbook songs were more likely to be newer pieces, many of them originating in the theatres and pleasure gardens. This was also the case with the ‘slip songs’, several of which could be printed on a half-sheet which would then be cut into individual songs with a format of 1/4o or 1/8o. The Dicey catalogues of 1754 advertised: ‘There are near Two Thousand different Sorts of SLIPS; of which the New Sorts coming out almost daily render it impossible to make a Complete Catalogue.’ By 1764 the figure was ‘near Three Thousand’. Printed on one side only, slip songs can be considered as small broadsides.54

After the mid-century, more of the old ballads were being printed as chapbooks by some booksellers. Just a handful of ballads printed on broadsides by Samuel Harward in Tewkesbury survive, but more than eighty ballad chapbooks do, many of which correspond with the Dicey/Marshall old ballads. Eyres in Warrington, the Swindells family in Manchester, and the Angus family in Newcastle all favoured the chapbook format for ballads and songs, and in Scotland the chapbook was the dominant format from the 1770s until the broadside songs printed by the Poet’s Box operations in Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Dundee came along in the mid-nineteenth century. In London and the south of England, however, broadsides continued as the typical format for single songs, with a reduction in the size of the sheet to something more like a quarto coming in during the first decades of the nineteenth century, often with two songs on a sheet which could be separated as slips. These are the well-known sheets issued by Pitts and Catnach and their successors, among which can be found many of the folk songs that would be collected from singers before the First World War.

This north–south differentiation of format does appear to have been a real thing, although no really satisfactory explanation has been advanced for it. Chapbooks containing several songs might have represented better value for money, and might have been easier for chapmen to carry in rural areas. Conversely, in urban environments there may have been more call for sheets printed on one side only which could be pinned up and displayed against walls or on railings. Equally, there are anomalies, such as James Chalmers III of Aberdeen, who typically printed chapbooks, but in 1775/6 printed a series of forty (surviving) ballad and song broadsides, nearly all of which are dated quite precisely.55 Moreover, the chapbook remained the favoured format for all kinds of cheap prose literature, at least until execution broadsides that combined prose and verse started to become widespread in England in the nineteenth century.

Chapmen, itinerant pedlars, or ‘flying stationers’ as they were called in Scotland, were probably always more important to the trade in rural areas. For that reason, the pedlar selling cheap printed matter at markets and fairs, or coming to the cottage door, probably persisted longer in Scotland than elsewhere.56 There were more provincial bookshops in England from an earlier date, such as the Swindells bookshop in Manchester cited above. Samuel Harward’s imprints advertising his chapbooks for sale at his shops in Tewkesbury, Gloucester, and Cheltenham, and also from Miss Holt in Upton-upon-Severn, illustrate the concurrence of the wholesale and retail trade.57 Even in Scotland, William Bannerman recalled penny chapbooks and plain and coloured prints displayed in the window of Agnes Thomson’s bookshop in Aberdeen around the turn of the century.58

Nevertheless, from the last quarter of the seventeenth century and right through the eighteenth there were successive pieces of legislation intended to regulate and license hawkers, pedlars, and petty chapmen. One of the arguments being advanced was that at the beginning of the period there were around 10,000 pedlars in England.59 Not all of them were carrying printed matter, but from booksellers’ advertisements it is reasonable to infer that many of them were. Oskar Cox Jensen has proposed two patterns of activity for the itinerant traders in print: a ‘hub-hinterland model’, whereby a chapman would be based on an urban centre, which would provide a supply of printed material, but would make excursions into the surrounding districts, to markets, fairs, and villages; and a ‘long-distance model’, whereby a chapman would range much more widely, acquiring stock in the towns en route.60 The latter, perhaps less common, model derives particularly from the colourful autobiographies of characters like John Magee, David Love, and William Cameron (‘Hawkie’), mostly describing the trade towards the end of the century.

For the earlier period, information on itinerant sellers of cheap print is rather more sparse. There are newspaper and court reports of ballad singers who came into conflict with the authorities, and literary observations about the nuisance they were perceived as causing in the streets. These need to be treated with caution, since they are frequently concerned with connecting ballad singing with crime and prostitution, which may well be true, but provides little information about the sale of printed matter. Visual depictions of ballad sellers are frequently either grotesquely satirical, as in Hogarth’s prints, or rather romantic, as with some of the series of Cries of London, although they do at least attest to the presence of pedlars in the streets.61 All these sorts of evidence show both men and women engaged in the sale of printed matter. Women certainly fulfilled important roles in the trade in cheap print — as booksellers and printers (often widows or other female relations who took over a bookselling business), ‘mercury-women’ who facilitated the distribution of early news-sheets and pamphlets, stationers and distributors (like Miss Holt and Agnes Thomson mentioned above), ballad singers and sellers, and possibly as authors too, even if they have often remained invisible and much remains to be researched.62

The matter of street literature

Besides the recurrent legendary stories and romances, jest books, and the like, the chapbook format lent itself to topical subjects such as shipwrecks, adventures, and the lives of criminals.63 Like the legendary and historical stories, some of the seemingly topical accounts also lie on the border between fact and fiction. A taste for imaginative literature runs through the corpus of cheap print. Lennard Davis refers to a ‘news/novels discourse’ which is manifest not just in the form of chapbook fiction but also in the ballads that describe in verse things like murders, battles, and strange natural phenomena.64 In other words, street literature ranged across fiction and non-fiction, catering for a wide variety of tastes, though presumably individual readers had their own favourite genres. Of canonical literature, however, only Robinson Crusoe, Moll Flanders, and The Pilgrim’s Progress achieved widespread circulation in chapbook abridgements.65

The Donaldson v. Becket judgement in 1774 brought to an end the regime of effective perpetual copyright, through which the major London booksellers had retained control of commercially valuable works of literature.66 Subsequently, canonical poetry and drama started to become available through series such as Bell’s Poets of Great Britain, Bell’s British Theatre, Bell’s Shakespeare, and Samuel Johnson’s The English Poets (with his Lives of the Poets), and novels by the likes of Defoe, Richardson, Fielding, Smollett, Goldsmith, Johnson, and Sterne were also reprinted in cheap editions.67 William St Clair maintains that a consequence of this increased availability of what he calls the ‘old canon’ authors was the demise within a generation of the chapbook histories and old ballads, which ‘died out, like the dinosaurs, as part of a sudden mass extinction’.68

This is certainly an exaggeration, and if some titles did die out, or were adapted into the expanding market for prose and verse aimed specifically at children, they were also replaced by new ballad titles and by new kinds of non-canonical fiction, which attest to an appetite for cheap print that was both continuing and expanding. Perhaps more importantly, St Clair poses (albeit in somewhat ambiguous fashion) the question of how far cheap print can be equated with the mentalities of its readership. Thus he argues that, since it was purely commercial pressures that ensured the persistence of certain titles before 1774 and their putative ‘mass extinction’ afterwards, then it cannot be claimed ‘that the texts reflected, in some special way, the mentalities of the readers, or catered for their needs and aspirations’, yet he also maintains that the same commercial pressures had ‘kept a large constituency of marginal readers in ancient ignorance’, which seems to mean that cheap print did shape their mentalities.69 A way around this apparent impasse is to accord a greater weight to the sheer diversity of cheap print that was available during the century. Once the full range of ballads, songs, chapbook stories (old and new), and topical, satirical, instructional, and devotional titles is brought into view, then the mentalities argument can be bypassed simply because it is effectively overwhelmed by the sheer volume of print.

The extent of the trade

It should be clear that the foregoing discussion has barely scraped the surface of everything that could come under the rubric of street literature or cheap print, and that it has necessarily drawn heavily on the existing scholarship. This has meant something of a bias towards ballads and songs, chapbook fiction, and printed images.70Almanacs, which were printed and sold in seemingly vast quantities, have been treated rather differently, partly because the Stationers’ Company held a monopoly on their publication up until 1775, and partly because their contents shade into astrology and invite a ‘history of ideas’ kind of approach, even though the lists of markets and fairs that they also carried were quite pertinent to the itinerant print trade.71 Aside from the Cheap Repository Tracts and the Scottish ‘religious chapbooks’,72 the standing of cheap theological and devotional titles has not been much investigated. Many sermons and similar works were issued by the same booksellers who published ballads and chapbooks, but there may be a distinction to be drawn between genuinely ‘popular’, commercial titles such as The Pilgrim’s Progress, Watts’s Divine Songs, or Richard Baxter’s A Call to the Unconverted, which went through many editions,73 and sermons that might have been financed either by their authors or by religious bodies for polemical purposes.74

Likewise, it is an open question how prose pamphlets and slip songs with political and satirical content should be viewed, as compared with the old ballads, chapbook histories, or topical chapbook accounts of shipwrecks, adventures, and the lives of notorious criminals. There are many sets of political or polemical verses in broadside or small pamphlet format listed in David Foxon’s catalogue of English verse from 1701 to 1750.75 To take an example almost at random, a poem on the Duke of Marlborough’s continental exile, albeit in broadsheet format and priced at 2d., still does not feel part of the mainstream of ‘popular’ or ‘plebeian’ street literature as established by the existing scholarship.76 Perhaps the difference lies in the heroic couplets (with a brace to link the final three rhyming lines) and the political subject, or in the typography itself, with a decorated drop-capital ‘G’ to begin the poem, well-spaced lines of verse, and extensive use of capital letters, and the fact that it was printed on paper bearing a halfpenny tax stamp.

Later, there are at least nine different slip songs concerning Admiral John Byng, executed in 1757, in the Madden collection.77 All bar one are without imprint, the exception being a song called A Rueful Story, which exists in at least two different editions, one of them with a satirical imprint.78 The fact that each of the slips indicates a tune at least implies public performance, and the number of songs suggests the subject enjoyed a certain notoriety. Nevertheless, there is no evidence that these songs were ever printed except around 1756/7. The slip song format, more widespread in the second half of the century, probably lent itself more readily to items of transient popularity, which would include songs from the theatres and pleasure gardens. The contrast is with the old ballads and chapbook histories, many of which the English Short Title Catalogue shows were published in successive editions over extended periods of time.

Nevertheless, the distinctions suggested here are far from clear-cut. Moreover, we know very little about the print runs of any of these items, aside from the hundreds of thousands of almanacs printed for the Stationers’ Company.79 Estimates are far lower for chapbooks and broadsides — print runs in the region of a minimum 1,000–2,000 and 2,000–4,000, respectively — but this is largely guesswork.80 Leaping ahead to the 1850s (admittedly a time when printing technology had advanced), the Glasgow Poet’s Box provides evidence of editions of 10,000 for some broadside songs, and some of them went into further reprints.81

There is, though, an intriguing bit of direct evidence for street literature titles right in the middle of our period, in the form of an Old Bailey trial in 1759 which centred on the theft of some seventeen reams of printed paper from Larkin How’s warehouse:

Sarah, wife of Solomon Cater, was indicted for stealing eight reams of part of Robin-Hood’s Garland, value 20

s

. two reams of the history of the Kings and Queens, value 5

s

. three reams of the lives of the Apostles, value 5

s

. and four reams of several sorts of histories, value 20

s

. the property of Larkin How, privately in his warehouse, Aug. 1.

82

The easiest to interpret of the stolen items is the ‘two reams of the history of the Kings and Queens’, taken to refer to The Wand’ring Jew’s Chronicle, an old ballad (written by Martin Parker and first printed in the previous century), printed by How as an eight-page chapbook.83 If a ream was 480 sheets, and assuming no wastage, then the print run must have been at least 960 copies. The trial record states that Sarah Cater sold the stolen reams to the proprietors of chandlers’ and cheesemongers’ shops, for use as wrapping paper. Paper itself was one of the most significant costs for the print trade in the hand-press period, though admittedly somewhat less so for cheap print on inferior grades of paper.84

Just one copy of How’s Wand’ring Jew’s Chronicle is known to have survived, but the ballad itself survives in fifteen different editions or issues between c.1660 and c.1830.85 The label of ‘ephemera’ is not helpful, since the customer laying out 1d. or 6d. or 1s. can be assumed to have been buying something that they wanted to keep. The contrast would be with something like a handbill distributed gratis (or perhaps an almanac, the worth of which was by its very nature time-limited). Moreover, access to songs and stories (whether fiction or non-fiction) was not confined to the owner of the printed item at a time when reading mostly meant reading out loud and there was singing in the streets. It remains difficult to infer the ‘popularity’ of titles from observations such as these. It does, though, seem permissible to infer the aesthetic value of songs and stories that were read and sung, images displayed, works of instruction consulted and works of devotion taken to heart, even if from the bookseller’s perspective the purpose of printing them was primarily to sell them.

1 Early trade descriptions do not clearly distinguish between printers and what would now be called publishers, and the term ‘booksellers’ was in general use. See further James Raven, The Business of Books: Booksellers and the English Book Trade, 1450–1850 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007), esp. pp. 4–5.

2 Laurence Fontaine, History of Pedlars in Europe, trans. Vicki Whittaker (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996).

3 Margaret Spufford, The Great Reclothing of Rural England: Petty Chapmen and their Wares in the Seventeenth Century (London: Hambledon Press, 1984); Margaret Spufford, Small Books and Pleasant Histories: Popular Fiction and its Readership in Seventeenth-Century England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985 [1981]), esp. pp. 111–28.

4 David Atkinson, ‘Street Ballad Singers and Sellers, c.1730–1780’, Folk Music Journal, 11.3 (2018), 72–106; Oskar Cox Jensen, The Ballad-Singer in Georgian and Victorian London (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

5 John Feather, The Provincial Book Trade in Eighteenth-Century England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), pp. 28–31; David Stoker, ‘The English Country Book Trades in 1784–5’, in The Human Face of the Book Trade: Print Culture and its Creators (Winchester: St Paul’s Bibliographies; New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 1999), pp. 13–27; James Raven, The Business of Books: Booksellers and the English Book Trade, 1450–1850 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007), pp. 141–43.

6 Henry Dunckley (ed.), Bamford’s ‘Passages in the Life of a Radical’ and ‘Early Days’, 2 vols (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1905), I, 87.

7 Robert D. Hume, ‘The Value of Money in Eighteenth-Century England: Incomes, Prices, Buying Power — and Some Problems in Cultural Economics’, Huntington Library Quarterly, 77 (2015), 373–416 (p. 381).

8 Michael F. Suarez, SJ, ‘Introduction’, in The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, vol. 5, 1695–1830, ed. Michael F. Suarez, SJ, and Michael L. Turner (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), pp. 1–35 (pp. 8–12).

9 Roger Chartier, Forms and Meanings: Texts, Performances, and Audiences from Codex to Computer (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995), pp. 83–97.

10 For example, Hannah Barker and David Vincent (eds), Language, Print and Electoral Politics, 1790–1832: Newcastle-under-Lyme Broadsides (Woodbridge: Boydell Press for the Parliamentary History Yearbook Trust, 2001).

11 Feather, Provincial Book Trade, p. 65; C. Y. Ferdinand, ‘Newspapers and the Sale of Books in the Provinces’, in The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, vol. 5, 1695–1830, ed. Michael F. Suarez, SJ, and Michael L. Turner (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), pp. 434–47; Robert S. Thomson, ‘The Development of the Broadside Ballad Trade and its Influence upon the Transmission of English Folksongs’ (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Cambridge, 1974), pp. 97–99.

12Roger’s Delight; or, The West Country Christ’ning and Gossiping (Northampton: printed by R. Raikes and W. Dicey; and sold by Matthias Dagnel, in Aylesbury and Leighton; Stephen Dagnel, in Chesham; William Ratten, in Coventry; Thomas Williams, in Tring, booksellers; Nathan Ward, in Sun Lane, in Reading; William Royce, in St Clement’s, Oxford; Paul Stephens, in Bister; Anthony Thorpe, at the White Swan, in St Albans; Mr Franks, in Wooburne; William Peachy, near St Benet’s Church, in Cambridge; and by Chururd [sic] Brady, in St Ives; at all which places are sold all sorts of ballads, broadsheets, and histories, with finer cuts, better print, and as cheap as at any place in England) [ESTC T45185]; on verso The Bubblers Bubbled; or, The Devil Take the Hindmost (cut and printed at Northampton; where country shopkeepers and others may be furnish’d with all sorts of broadsheets, ballads, and histories, as cheap, and much better done than at any printing office in England, 1720) [ESTC T142941].

13The Force of Nature; or, The Loves of Hippollito and Dorinda, a Romance (Northampton: printed by R. Raikes and W. Dicey, over against All Saints Church, 1720), price 3d. [ESTC T40015]; ’Tis All a Cheat; or, The Way of the World […] to which is added, An Ode upon Solitude (Northampton: printed by R. Raikes and W. Dicey, over against All Saints Church, 1720), price 3d. [ESTC T225265].

14 John Ashton, Chap-books of the Eighteenth Century (London: Chatto and Windus, 1882), p. ix.

15The Birds Lamentation (Northampton: printed by Wm. Dicey; and sold at Mr Burnham’s snuff shop, and by Mathias Dagnell, bookseller, in Aylesbury; Paul Stevens, in Bicester; William Ratten, bookseller, in Coventry; Caleb Ratten, bookseller, in Harborough; Thomas Williams, in Tring; Anthony Thorpe, in St Albans; William Peachey, near St Bennet’s Church, in Cambridge; Mary Timbs, in Newport Pagnell; John Timbs, in Stony Stratford; Jeremiah Roe, in Derby; John Hirst, in Leeds; Thomas Gent, in York; John White, printer, in Newcastle upon Tyne; and by Churrude Brady, in St Ives; at all which places chapmen and travellers may be furnish’d with the best sorts of old and new ballads, broadsheets, &c.) [ESTC N15639].

16 This paragraph is based on David Stoker, ‘Another Look at the Dicey-Marshall Publications: 1736–1806’, The Library, 7th ser., 15 (2014), 111–57. See also David Stoker, ‘Street Literature in England at the End of the Long Eighteenth Century’, in Street Literature of the Long Nineteenth Century: Producers, Sellers, Consumers, ed. David Atkinson and Steve Roud (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017), pp. 60–97; Timothy Clayton, ‘Dicey family (per. c.1710–c.1800)’, ODNBhttp://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/65524.

17 For the seventeenth-century ballad partnership, see Cyprian Blagden, ‘Notes on the Ballad Market in the Second Half of the Seventeenth Century’, Studies in Bibliography, 6 (1954), 161–80. Among those whose statements can be read as implying a direct transfer of ownership from this partnership to the Dicey/Marshall firm are Leslie Shepard, John Pitts, Ballad Printer of Seven Dials, London, 1765–1844 (London: Private Libraries Association, 1969), pp. 22–23; Thomson, ‘Development of the Broadside Ballad Trade’, pp. 82–83; William St Clair, The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), pp. 341, 500–01.

18 The 1712 entry is discussed in more detail in Chapter 6 of this volume.

19 Plomer, Dictionary, 1668 to 1725, pp. 155–56.

20 John Nichols, Literary Anecdotes of the Eighteenth Century, 9 vols (London: printed for the author; by Nichols, Son, and Bentley, 1812–15), VIII, 168n.

21 Plomer, Dictionary, 1668 to 1725, p. 294.

22 Plomer, Dictionary, 1668 to 1725, pp. 53, 220–21.

23 Plomer, Dictionary, 1726 to 1775, pp. 127–28.

24 Chapter 2 of this volume.

25The Siege of Gaunt; or, The Valorous Acts of Mary Ambree (printed for Joseph Hinson, at the Sun and Bible, in Giltspur Street, near Pye Corner) [ESTC T206965]; A Gold Chain of Four Links, to Draw Poor Souls to their Desired Habitation (London: printed by J. Hinson, at the Sun and Bible, in Giltspur Street, near Pye Corner) [ESTC T104533].

26 Chapter 6 of this volume.

27 See David Atkinson, ‘Survivals in Cheap Print, 1750–1800: Some Preliminary Estimates’, The Library, 7th ser., 24 (2023), 154–68.

28 Nathan Garvey, ‘A Dynasty on the Margins of the Trade: The Bailey Family of Printers, ca. 1740–1840, Part 1’, Script & Print, 32.3 (2009), 144–62.

29 David Atkinson, ‘Street Literature Printing in Stonecutter Street (1740s–1780s)’, Publishing History, 78 (2018), 9–53; David Atkinson, ‘Ballad and Street Literature Printing in Petticoat Lane, 1740s–1760s’, Traditiones, 47.2 (2018), 107–17.

30 David Atkinson, ‘Bellman’s Sheets – Between Street Literature and Ephemera’, in Transient Print: Essays in the History of Printed Ephemera, ed. Lisa Peters and Elaine Jackson (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2023), pp. 107–29.

31The King and Tinker’s Garland; containing Three Excellent Songs: 1. King James the First and the Fortunate Tinker; 2. The Taylor Outwitted by the Sailor; 3. The Lawyer and the Farmer’s Daughter (Sheffield: printed by John Garnet, at the Castle Green Head, near the Irish Cross, Sept. 1745) [ESTC T29425].

32A New Song, call’d The Duke of Cumberland’s Victory over the Scotch Rebels at Cullodon-Moor, near Inverness + England’s Glory; or, Duke William’s Triumph over the Rebels in Scotland (Sheffield: printed by Francis Lister, near the Shambles, 1746) [ESTC T39960].

33Constance and Anthony; or, An Admirable Northern Story (Gosport: printed by J. Philpo[t]) [ESTC R232923].

34 Martin Holmes, ‘Samuel Gamidge: Bookseller in Worcester (c.1755–1777)’, in Images & Texts: Their Production and Distribution in the 18th and 19th Centuries, ed. Peter Isaac and Barry McKay (Winchester: St Paul’s Bibliographies; New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 1997), pp. 11–52.

35 See Chapters 4 and 5 of this volume for case studies of the regional print trade in Norwich and Penrith.

36 David Atkinson, ‘Thomas Sabine and Son: Street Literature and Cheap Print at the End of the Eighteenth Century’, in A Notorious Chaunter in B Flat and Other Characters in Street Literature, ed. David Atkinson and Steve Roud (London: Ballad Partners, 2022), pp. 161–85; also Chapter 12 of this volume.

37 David Atkinson, ‘Samuel Harward: Ballad and Chapbook Printer in Tewkesbury, Gloucester, and Cheltenham’, in A Notorious Chaunter in B Flat and Other Characters in Street Literature, ed. David Atkinson and Steve Roud (London: Ballad Partners, 2022), pp. 139–60.

38 Michael Perkin, ‘William Eyres and the Warrington Press’, in Aspects of Printing from 1600, ed. Robin Myers and Michael Harris (Oxford: Oxford Polytechnic Press, 1987), pp. 69–89; P. O’Brien, Eyres’ Press, Warrington (1756–1803): An Embryo University Press (Wigan: Owl Books, 1993).

39 Leo John De Freitas, The Banbury Chapbooks, Banbury Historical Society, vol. 28 (Banbury: Banbury Historical Society, in association with Robert Boyd Publications, 2004).

40 John Feather, ‘The Country Trade in Books’, in Spreading the Word: The Distribution Networks of Print, 1550–1850, ed. Robin Myers and Michael Harris (Winchester: St Paul’s Bibliographies; New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 1998 [1990]), pp. 165–83 (p. 166).

41 David Stoker, ‘John Marshall, John Evans, and the Cheap Repository Tracts’, Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 107 (2013), 81–118.

42 G. H. Spinney, ‘Cheap Repository Tracts: Hazard and Marshall Edition’, The Library, 4th ser., 20 (1939), 295–340 (p. 303); St Clair, Reading Nation, p. 354 and n. 53, sees the coarser paper as destined to be used in the privy.

43 Chapter 10 of this volume.

44 Adam Fox, The Press and the People: Cheap Print and Society in Scotland, 1500–1785 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020). See Chapter 9 of this volume for the later decades.

45 Chapter 9 of this volume.

46OED, chap-book, n.

47 Barry McKay, An Introduction to Chapbooks (Oldham: Incline Press, 2003), pp. 33–34; Jan Fergus, Provincial Readers in Eighteenth-Century England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 161.

48 For example: F. W. Ratcliffe, ‘Chapbooks with Scottish Imprints in the Robert White Collection, the University Library, Newcastle upon Tyne’, The Bibliotheck, 4 (1963–66), 88–174 (p. 92); John Simons (ed.), Guy of Warwick and Other Chapbook Romances: Six Tales from the Popular Literature of Pre-industrial England (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 1998), p. 4.

49 For example: Victor E. Neuburg, Chapbooks: A Guide to the Reference Material on English, Scottish and American Chapbook Literature of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, 2nd edn (London: Woburn Press, 1972), p. 1; Edward J. Cowan and Mike Patterson, Folk in Print: Scotland’s Chapbook Heritage, 1750–1850 (Edinburgh: John Donald, 2007), p. 12.

50 For example: Robin Hood’s Garland (sold by S. Gamidge, in High Street, Worcester; by Mr Daw, cutler, in Taunton; and by Mr Radnall, in Bewdley) [ESTC T169308].

51 M. O. Grenby, ‘Chapbooks, Children, and Children’s Literature’, The Library, 7th ser., 8 (2007), 277–303 (p. 278).

52 Chapter 6 of this volume.

53 Spufford, Small Books and Pleasant Histories, pp. 99–100; Pepys’s ‘small merry books’ are listed on pp. 263–66.

54 See Chapters 7 and 8 of this volume for slip songs and songs from the theatres and pleasure gardens.

55 David Atkinson, ‘The Aberdeen Ballad Broadsides of 1775/6’, in A Notorious Chaunter in B Flat and Other Characters in Street Literature, ed. David Atkinson and Steve Roud (London: Ballad Partners, 2022), pp. 68–92.

56 John Morris, ‘The Scottish Chapman’, in Fairs, Markets and the Itinerant Book Trade, ed. Robin Myers, Michael Harris, and Giles Mandelbrote (New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press; London: British Library, 2007), pp. 159–86.

57 For example: