3,68 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Delphi Publishing Ltd

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Delphi Series Fourteen

- Sprache: Englisch

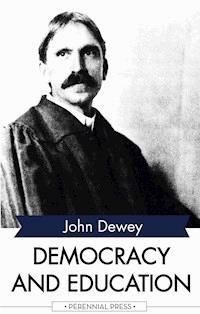

One of the most prominent scholars of the first half of the twentieth century, John Dewey was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer. A co-founder of the pragmatism movement, Dewey was also a pioneer in functional psychology, an innovative theorist of democracy and a leader of the progressive movement in education. For the first time in publishing history, this eBook presents Dewey’s complete works, with numerous illustrations, rare texts, informative introductions and the usual Delphi bonus material. (Version 1)

* Beautifully illustrated with images relating to Dewey’s life and works

* Concise introductions to the major texts

* All the published books, with individual contents tables

* Works appear with their original hyperlinked footnotes

* Rare texts appearing for the first time in digital publishing

* Images of how the books were first published, giving your eReader a taste of the original texts

* Excellent formatting of the texts

* Ordering of texts into chronological order

CONTENTS:

The Books

Psychology (1887)

My Pedagogic Creed (1897)

The School and Society (1899)

Leibniz’s New Essays Concerning the Human Understanding (1902)

The Child and the Curriculum (1902)

Studies in Logical Theory (1903)

Ethics (1908)

Moral Principles in Education (1909)

How We Think (1910)

The Influence of Darwin on Philosophy (1910)

Interest and Effort in Education (1913)

Schools of To-morrow (1915)

Democracy and Education (1916)

Essays in Experimental Logic (1916)

Reconstruction in Philosophy (1920)

Letters from China and Japan (1920)

Human Nature and Conduct (1922)

Experience and Nature (1925)

The Public and Its Problems (1927)

Impressions of Soviet Russia and the Revolutionary World (1929)

The Quest for Certainty (1929)

Individualism Old and New (1931)

Philosophy and Civilization (1931)

Art as Experience (1934)

A Common Faith (1934)

Liberalism and Social Action (1935)

The Philosophy of the Arts (1938)

Experience and Education (1938)

Logic, the Theory of Inquiry (1939)

Theory of Valuation (1939)

Freedom and Culture (1939)

Articles in ‘Popular Science Monthly’

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 10982

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

The Complete Works of

JOHN DEWEY

(1859-1952)

Contents

The Books

Psychology (1887)

My Pedagogic Creed (1897)

The School and Society (1899)

Leibniz’s New Essays Concerning the Human Understanding (1902)

The Child and the Curriculum (1902)

Studies in Logical Theory (1903)

Ethics (1908)

Moral Principles in Education (1909)

How We Think (1910)

The Influence of Darwin on Philosophy (1910)

Interest and Effort in Education (1913)

Schools of To-morrow (1915)

Democracy and Education (1916)

Essays in Experimental Logic (1916)

Reconstruction in Philosophy (1920)

Letters from China and Japan (1920)

Human Nature and Conduct (1922)

Experience and Nature (1925)

The Public and Its Problems (1927)

Impressions of Soviet Russia and the Revolutionary World (1929)

The Quest for Certainty (1929)

Individualism Old and New (1931)

Philosophy and Civilization (1931)

Art as Experience (1934)

A Common Faith (1934)

Liberalism and Social Action (1935)

The Philosophy of the Arts (1938)

Experience and Education (1938)

Logic, the Theory of Inquiry (1939)

Theory of Valuation (1939)

Freedom and Culture (1939)

Articles in ‘Popular Science Monthly’

The Delphi Classics Catalogue

© Delphi Classics 2024

Version 1

Browse our Main Series

Browse Ancient Classics

Browse the Medieval Library

Browse our Poets

Browse our Art eBooks

Browse the Classical Music series

The Complete Works of

JOHN DEWEY

By Delphi Classics, 2024

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of John Dewey

First published in the United Kingdom in 2024 by Delphi Classics.

© Delphi Classics, 2024.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 80170 188 4

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: [email protected]

www.delphiclassics.com

Explore Philosophy at Delphi Classics…

The Books

Burlington, Vermont — Dewey’s birthplace. This lithograph was produced a year before his birth in 1858.

Church Street, Burlington, as depicted on a 1907 postcard

Burlington in more recent times

Dewey as a young man

Psychology (1887)

Psychology was first published by Harper and Brothers in New York in 1887. Dewey revised the book over the next four years and released second and third editions reflecting his developing views and theories. The author was born into a family of four sons with modest means; his mother was a devoted and pious Christian and his father was a well-read man. After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from the University of Vermont in 1879, Dewey taught at a high school in Oil City, Pennsylvania, for two years before enduring a brief and unhappy stint as a primary school teacher in the winter term of 1881 in Charlotte, Vermont. He soon abandoned school teaching to earn his graduate degrees at John Hopkins University after being encouraged by two of his articles appearing in The Journal of Speculative Philosophy.

H. A. P Torrey, the philosophy professor at the University of Vermont, was an important early mentor to Dewey; he privately tutored his former student even after graduation. In the September of 1884, Dewey began teaching at the University of Michigan after one of his former professors, George S. Morris, helped him attain the position. It was during this period of lecturing that he released the first edition of Psychology, which he intended as a textbook about the subject. The work promotes psychology not only as an introduction to philosophy, but as a discipline or field of study that can be used to resolve some of the most challenging and disputed philosophical questions throughout the centuries.

H. A. P Torrey was noted as a ‘sound philosopher’, as well as possessing a strong interest in Immanuel Kant.

University of Vermont, Dewey’s alma mater, c. 1900

The first edition

CONTENTS

PREFACE.

CHAPTER I. THE SCIENCE AND METHOD OF PSYCHOLOGY.

CHAPTER II. THE MIND AND ITS MODES OF ACTIVITY.

PART I. KNOWLEDGE.

CHAPTER III. ELEMENTS OF KNOWLEDGE.

CHAPTER IV. PROCESSES OF KNOWLEDGE.

CHAPTER V. STAGES OF KNOWLEDGE. — PERCEPTION.

CHAPTER VI. MEMORY.

CHAPTER VII. IMAGINATION.

CHAPTER VIII. THINKING.

CHAPTER IX. INTUITION.

PART II. FEELING.

CHAPTER X. INTRODUCTION TO FEELING.

CHAPTER XI. SENSUOUS FEELING.

CHAPTER XII. FORMAL FEELING.

CHAPTER XIII. DEVELOPMENT OF QUALITATIVE FEELINGS.

CHAPTER XIV. INTELLECTUAL FEELINGS.

CHAPTER XV. ÆSTHETIC FEELING.

CHAPTER XVI. PERSONAL FEELING.

PART III. THE WILL

CHAPTER XVII. SENSUOUS IMPULSES.

CHAPTER XVIII. DEVELOPMENT OF VOLITION.

CHAPTER XIX. PHYSICAL CONTROL.

CHAPTER XX. PRUDENTIAL CONTROL.

CHAPTER XXI. MORAL CONTROL.

CHAPTER XXII. WILL AS THE SOURCE OF IDEALS AND OF THEIR REALIZATION.

APPENDIX A.

APPENDIX B.

The first edition’s title page

Dewey, close to the time of publication

PREFACE.

ANY BOOK, WRITTENas this one is, expressly for use in class-room instruction, must meet one question with which text-books outside the realm of philosophy are not harassed. What shall be its attitude towards philosophic principles? This is a question which may be suppressed, but cannot be avoided. The older works, indeed, were not so much troubled by it, for it is only recently that psychology has attained any independent standing. As long as psychology was largely a compound of logic, ethics, and metaphysics, the only thing possible was to serve this compound, mingled with extracts from the history of philosophy. And it must not be forgotten that such a course had one decided advantage: it made psychology a good introduction to the remaining studies of the philosophic curriculum. But at present, aside from the fact that there is already an abundance of text-books of this style, which it were idle to increase, psychology seems deserving of a treatment on its own account.

On the other hand, there are books which attempt to leave behind all purely philosophic considerations, and confine themselves to the facts of scientific psychology. Such books certainly have the advantage of abandoning — or, at least, of the opportunity of abandoning — a mass of material which has no part nor lot in psychology, and which should long ago have been relegated to the history of metaphysics. But one can hardly avoid raising the question whether such surrender of philosophic principles be possible. No writer can create nor recreate his material, and is it quite likely that the philosophic implications embedded in the very heart of psychology are not got rid of when they are kept out of sight. Some opinion regarding the nature of the mind and its relations to reality will show itself on almost every page, and the fact that this opinion is introduced without the conscious intention of the writer may serve to confuse both the author and his reader.

But to me one other consideration seems decisive against such a course. It does not have due reference to the historic conditions of our instruction. One essential element in the situation is that it is the custom of our colleges to make psychology the path by which to enter the fields of philosophy.

How, then, shall we unite the advantages of each class of text-books? That is to say, how shall we make our psychology scientific and up to the times, free from metaphysics — which, however good in its place, is out of place in a psychology — and at the same time make it an introduction to philosophy in general? While I cannot hope to have succeeded in presenting a psychology which shall satisfactorily answer this question, it does appear to me an advantage to have kept this question in mind, and to have written with reference to it. I have accordingly endeavored to avoid all material not strictly psychological, and to reflect the investigations of scientific specialists in this branch; but I have also endeavored to arrange the material in such a way as to lead naturally and easily to the problems which the student will meet in his further studies, to suggest the principles along which they shall find their solutions, and, above all, to develop the philosophic spirit. I am sure that there is a way of raising questions, and of looking at them, which is philosophic; a way which the beginner can find more easily in psychology than elsewhere, and which, when found, is the best possible introduction to all specific philosophic questions. The following pages are the author’s attempt to help the student upon this way.

CHAPTER I. THE SCIENCE AND METHOD OF PSYCHOLOGY.

§ 1. The Subject-matter of Psychology.

DEFINITIONOF PSYCHOLOGY: Psychology is the Science of the Facts or Phenomena of Self — This definition cannot be expected to give, at the outset, a clear and complete notion of what the science deals with, for the reason that it is the business of psychology to clear up and develop what is meant by facts of self. Other words, however, may be used to bring out the meaning somewhat. Ego is a term used to express the fact that self has the power of recognizing itself as I, or a separate existence or personality. Mind is also a term used, and suggests especially the fact that self is intelligent. Soul is a term which calls to mind the distinction of the self from the body, and yet its connection with it. Psychical is an adjective used to designate the facts of self, and suggests the contrast with physical phenomena, which exist externally. Subject is often used, and expresses the fact that the self lies under and holds together all feelings, purposes, and ideas; and serves to differentiate the self from the object — that which lies over against self. Spirit is a term used, especially in connection with the higher activities of self, and calls to mind its distinction from matter and mechanical modes of action.

Fundamental Characteristic of Self. — This is the fact of consciousness. The self not only exists, but it knows that it exists; psychical phenomena are not only facts, but they are facts of consciousness. A stick, a stone, exists and undergoes changes; that is, has experiences. But it is aware neither of its existence nor of these changes. It does not, in short, exist for itself. It exists only for some consciousness. Consequently the stone has no self. But the soul not only is, and changes, but it knows that it is, and what these experiences are which it passes through. It exists for itself. That is to say, it is a self. What distinguishes the facts of psychology from the facts of every other science is, accordingly, that they are conscious facts.

Consciousness. — Consciousness can neither be defined nor described. We can define or describe anything only by the employment of consciousness. It is presupposed, accordingly, in all definition; and all attempts to define it must move in a circle. It cannot be defined by discriminating it from the unconscious, for this either is not known at all, or else is known only as it exists for consciousness. Consciousness is necessary for the definition of what in itself is unconscious. Psychology, accordingly, can study only the various forms of consciousness, showing the conditions under which they arise.

The Self or Individual. — We have seen that the peculiar characteristic of the facts of self is that they are conscious, or exist for themselves. This implies further that the self is individual, and all the facts of self are individual facts. They are unique in this. A fact of physics, or of chemistry, for the very reason that it does not exist for itself, exists for anybody or everybody who wishes to observe it. It is a fact which can be known as directly and immediately by one as by another. It is universal, in short. Now, a fact of psychology does not thus lie open to the observation of all. It is directly and immediately known only to the self which experiences it. It is a fact of my or your consciousness, and only of mine or yours.

Communication of an Individual State. — It may be communicated to others, but the first step in this communication is changing it from a psychical fact to a physical fact. It must be expressed through non-conscious media — the appearance of the face, or the use of sounds. These are purely external. They are no longer individual facts. The next step in the communication is for some other individual to translate this expression, or these sounds, into his own consciousness. He must make them part of himself before he knows what they are. One individual never knows directly what is in the self of another; he knows it only so far as he is able to reproduce it in his own self. The fact of the existence of self or of consciousness is, accordingly, a unique individual fact. Psychology deals with the individual, or self, while all other sciences, as mathematics, chemistry, biology, etc., deal with facts which are universal, and are not facts of self, but facts presented to the selves or minds which know them.

Relation of Psychology to Other Sciences. — Psychology holds, therefore, a twofold relation to all other sciences. On the one hand, it is co-ordinated with other sciences, as simply Laving a different and higher subject-matter than they. The student may begin with bodies most remote from himself, in the science of astronomy. He may then study the globe upon which he lives, in geography, geology, etc. He may then study the living beings upon it, botany, zoology, etc. Finally he may come to his own body, and study human physiology. Leaving his body, he may then study his own self. Such a study is psychology. Thus considered, psychology is evidently simply one science among others.

Psychology a Central Science. — But this overlooks one aspect of the case. All the other sciences deal only with facts or events which are known; but the fact of knowledge thus involved in all of them no one of them has said anything about. It has treated the facts simply as existent facts, while they are also known facts. But knowledge implies reference to the self or mind. Knowing is an intellectual process, involving psychical laws. It is an activity which the self experiences. A certain individual activity has been accordingly presupposed in all the universal facts of physical science. These facts are all facts known by some mind, and hence fall, in some way, within the sphere of psychology. This science is accordingly something more than one science by the side of others; it is a central science, for its subject-matter, knowledge, is involved in them all.

The Universal Factor in Psychology. — It will be seen, therefore, that psychology involves a universal element within it, as well as the individual factor previously mentioned. Its subject-matter, or its content, is involved in all the sciences. Furthermore, it is open to all intelligences. This may be illustrated in case of both knowledge and volition. For example: I know that there exists a table before me. This is a fact of my knowledge, of my consciousness, and hence is individual. But it is also a possible fact for all intelligences whatever. The thing known is just as requisite for knowledge as the knowing; but the thing known is such for all mind whatever. It is, therefore, universal in its nature. While knowledge, therefore, as to its form is individual, as to its content it is universal. Knowledge may be defined as the process by which some universal element — that is, element which is in possible relation to all intelligences — is given individual form, or existence in a consciousness. Knowledge is not an individual possession. Any consciousness which in both form and content is individual, or peculiar to some one individual, is not knowledge. To obtain knowledge, the individual must get rid of the features which are peculiar to him, and conform to the conditions of universal intelligence. The realization of this process, however, must occur in an individual.

Illustration in Action. — Volition, or action, also has these two sides. The content of every act that I can perform already exists, i. e., is universal. But it has no existence for consciousness, does not come within the range of psychology, until I, or some self, perform the act, and thus give it an individual existence. It makes no difference whether the act be to write a sentence or tell the truth. In one case the pen, the ink, the paper, the hand with its muscles, and the laws of physical action which control writing already exist, and all I can do is to give to these separate universal existences an individual existence by reproducing them in my consciousness through an act of my own. In the other case the essence of the truth already exists, and all the self can do is to make it its own. It can give it individual form by reproducing this universal existence in consciousness or self.

Further Definition of Psychology. — Our original definition of psychology may now be expanded. Psychology is the science of the reproduction of some universal content or existence, whether of knowledge or of action, in the form of individual, unsharable consciousness. This individual consciousness, considered by itself, without relation to its content, always exists in the form of feeling; and hence it may be said that the reproduction always occurs in the medium of feeling. Our study of the self will, therefore, fall under the three heads of Knowledge, Will, and Feeling. Something more about the nature of each of these and their relations to each other will be given in the next chapter.

§ 2. Method of Psychology.

Need of Method. — The subject-matter of psychology is the facts of self, or the phenomena of consciousness. These facts, however, do not constitute science until they have been systematically collected and ordered with reference to principles, so that they may be comprehended in their relations to each other, that is to say, explained. The proper way of getting at, classifying, and explaining the facts introduces us to the consideration of the proper method of philosophy.

Method of Introspection. — In the first place, it is evident that, since the facts with which psychology has to do are those of consciousness, the study of consciousness itself must be the main source of knowledge of the facts. Just as the facts with which the physical sciences begin are those phenomena which are present to the senses — falling bodies, lightning, rocks, acids, trees, etc. — so psychical science must begin with the facts made known in consciousness. The study of conscious facts with a view to ascertaining their character is called introspection. This must not be considered a special power of the mind. It is only the general power of knowing which the mind has, directed reflectively and intentionally upon a certain set of facts. It is also called internal perception; the observation of the nature and course of ideas as they come and go, corresponding to external perception, or the observation of facts and events before the senses. This method of observation of facts of consciousness must ultimately be the sole source of the material, of psychology.

Defects of Introspection. — Introspection can never become scientific observation, however, for the latter means the direction of attention to certain facts according to some end or purpose. In observation of physical phenomena the things attended to remain entirely indifferent to and unchanged by the process of observation. In psychical events this is not so. The very act of attending to a psychical state changes its character, so that we observe, not what we meant to observe, but a comparatively artificial product. Since the mind’s supply of energy is limited, it may often occur that the very effort of attention will absorb most of it, and the facts which we wished to observe will vanish, and nothing remain but the tension of the mind. The rule for introspection must be, therefore, to use for the most part only accidental phenomena, such as are not expected, but are noticed in an incidental way.

It follows, therefore, that memory must be utilized rather than direct conscious perception; this remove from direct knowledge, however, renders the results subject to all the uncertainties of memory. It follows, also, that the most voluntary and distinct facts of mind will be most open to introspection, and that the more subtle and involuntary phenomena will necessarily either escape it or be transformed.

Failure as Explanatory Method. — So far we have dealt with introspection merely as giving us the facts of the science, and have seen that even here it fails. But its most conspicuous failure as method is when it is employed to account for or explain these facts. The facts can be explained only as they are related to each other, or reduced to more fundamental unities. How, introspection cannot show us these relations or unities.

It is necessarily limited to certain changing, extremely transitory phenomena, a succession of perceptions, ideas, desires, emotions, etc. The laws under which these facts come, the more fundamental activities which connect them, cannot be immediately perceived. Introspection will not even enable us to classify facts of consciousness. To classify them we must go beyond the present observed state and compare it with others which are no longer actually present. We do not gain much if we merely add memory to direct observation, and then compare; for classification requires a principle for its basis, and neither observation nor memory can supply this. Introspection, as a method of classification and explanation, has been noted rather as a source of illusions and deceptions in psychology than as the source of scientific comprehension. Introspection must, therefore, be carefully distinguished from self-knowledge. Knowledge of self is the whole sphere of intelligence or mind; introspection is the direction of mind in one limited channel, to the observation of particular states.

Experimental. — Amid these difficulties we can have recourse, first, to the experimental method. We cannot experiment directly with facts of consciousness, for the condition of experimentation — arbitrary variation for the sake of reaching some end, or eliminating some factor, or introducing some other to test its effects, together with the possibility of measuring the cause eliminated or introduced and the result occasioned — are not possible. But we can experiment, indirectly, through the connection of the soul with the body. The physical connections of the soul — that is, its relation to sense-organs and to the muscular system — are under our control, and can be experimented with, and thus, indirectly, changes may be introduced into consciousness. This is the department of psycho-physics. It differs from physiology in that the latter investigates only the physical processes of life, while psycho-physics makes use of these processes for the sake of investigating psychical states.

Object of Experimental Method. — Its object, as stated by Wundt, is to enable us to get results concerning the origin, composition, and temporal succession of psychical occurrences. Although this method has been employed but a short time, it has already yielded ample results in the spheres, especially, of the composition and relations of sensations, the nature of attention, and the time occupied by various mental processes. It will be noticed, therefore, that what is ordinarily called physiological psychology cannot aid psychology directly; the mere knowledge of all the functions of the brain and nerves does not help the science, except so far as it occasions a more penetrating psychological analysis, and thus supplements the deficiencies of introspection.

Comparative Method. — Even such results, however, are not complete. In the first place, the range of the application of this method is limited to those psychical events which have such connection with physical processes that they can be changed by changing the latter. And, in the second place, it does not enable us to get beyond the individual mind. There may be much in any one individual’s consciousness which is more or less peculiar and eccentric. Psychology must concern itself rather with the normal mind — with consciousness in its universal nature. Again, the methods already mentioned give us little knowledge concerning the laws of mental growth or development, the laws by which the mind passes from imperfect stages to more complete. This important branch of the study, called genetic psychology, is, for the most part, untouched either by the introspective or experimental methods. Both of these deficiencies are supplemented by the comparative method.

Forms of the Comparative Method. — Mind, as existing in the average human adult, may be compared with the consciousness (1) of animals, (2) of children in various stages, (3) of defective and disordered minds, (4) of mind as it appears in the various conditions of race, nationality, etc. The study of animal psychology is of use, especially in showing us the nature of the mechanical and automatic activities of intelligence, which are, in the human consciousness, apt to be kept out of sight by the more voluntary states. The instinctive side of mind has been studied mostly in animal life. The psychology of infants is of especial importance to us in connection with the origin and genetic connection of psychical activities. The study of minds which are defective through lack of some organ, as sight or hearing, serves to show us what elements of psychical life are due to these organs, while disordered or insane minds we may almost regard as psychical experiments performed by nature. The study of such cases shows the conditions of normal action, and the effects produced if some one of these conditions is altered or if the harmony of various elements is disturbed. The study of consciousness as it appears in various races, tribes, and nations extends that idea of mind to which we would be limited through the introspective study of our own minds, even if supplemented by observation of the manifestations of those about us.

Objective Method. — The broadest and most fundamental method of correcting and extending the results of introspection, and of interpreting these results, so as to refer them to their laws, is the study of the objective manifestations of mind. Mind has not remained a passive spectator of the universe, but has produced and is producing certain results. These results are objective, can be studied as all objective historical facts may be, and are permanent. They are the most fixed, certain, and universal signs to us of the way in which mind works. Such objective manifestations of mind are, in the realm of intelligence, phenomena like language and science; in that of will, social and political institutions; in that of feeling, art; in that of the whole self, religion. Philology, the logic of science, history, sociology, etc., study these various departments as objective, and endeavor to trace the relations which connect their phenomena. But none of these sciences takes into account the fact that science, religion, art, etc., are all of them products of the mind or self, working itself out according to its own laws, and that, therefore, in studying them we are only studying the fundamental nature of the conscious self. It is in these wide departments of human knowledge, activity, and creation that we learn most about the self, and it is through their investigation that we find most clearly revealed the laws of its activities.

Interpretation in Self-consciousness. — It must be borne in mind, however, that in studying psychological facts by any or all of these methods, the ultimate appeal is to self-consciousness. Hone of these facts mean anything until they are thus interpreted. As objective facts, they are not material of psychology, they are still universal, and must be interpreted into individual terms. What, for example, would language mean to an individual who did not have the power of himself reproducing the language? It would be simply a combination of uncouth sounds, and would teach him nothing regarding mind. The scowl of anger or the bent knees of devotion have no significance to one who is not himself capable of anger or of prayer. The psychical phenomena of infancy or of the insane would teach us nothing, because they would be nothing to us, if we did not have the power of putting ourselves into these states in imagination, at least, and thus seeing what they are like.

So the phenomena made known in physiological psychology, would have no value whatever for the science of psychology, if they were not interpretable into facts of consciousness. As physiological facts they are of no avail, for they tell us only about certain objective processes. These various methods, accordingly, are not so much a departure from self-consciousness, as a method of extending self-consciousness and making it wider and more general. They are methods, in short, of elevating us above what is purely contingent and accidental in self-consciousness, and revealing to us what in it is permanent and essential; what, therefore, is the subject-matter of psychology. It is with the true and essential self that psychology deals in order to ascertain its facts and explain them by showing their connections with each other.

CHAPTER II. THE MIND AND ITS MODES OF ACTIVITY.

INTRODUCTION. — PSYCHOLOGYhas to do with the facts of consciousness, and aims at a systematic investigation, classification, and explanation of these facts. We have to begin with a preliminary division of consciousness into cognitive, emotional, and volitional, although the justification of the definition, like that of psychology, cannot be seen until we have considered the whole subject. By consciousness as cognitive, we mean as giving knowledge or information, as appreciating or apprehending, whether it be appreciation of internal facts or of external things and events. By consciousness as emotional, we mean as existing in certain subjective states, characterized by either pleasurable or painful tone. Emotional consciousness does not, per se, give us information, but is a state of feeling. It is the affection of the mind. By consciousness as volitional, we mean as exerting itself for the attainment of some end.

Cognitive Consciousness. — Every activity or idea of the mind may be regarded as telling us about something. The mind is not what it was before this idea existed, but has added information about something to its store. The consciousness may be the perception of a tree, the conception of government, the idea of the law of gravitation, the news of the death of a friend, the idea of a house which one is planning to build; it may, in short, have reference to some object actually existing, to some relation or law; it may be concerned with one’s deepest feelings, or with one’s activities; but in any case, so far as it tells about something that is, or has happened, or is planned, it is knowledge — in short, it is the state of being aware of something, and so far as any state of consciousness makes us aware of something it constitutes knowledge.

Feeling. — But the state of consciousness is not confined to giving us information about something. It may also express the value which this information has for the self. Every consciousness has reference, not only to the thing or event made known by it, but also to the mind knowing, and is, therefore, a state of feeling, an affection of self. And since every state of consciousness is a state of self, it has an emotional side. Our consciousness, in other words, is not indifferent or colorless, but it is regarded as having importance, having value, having interest. It is this peculiar fact of interest which constitutes the emotional side of consciousness, and it signifies that the idea which has this interest has some unique connection with the self, so that it is not only a fact, an item of knowledge, but also a way in which the self is affected. The fact of interest, or connection with the self, may express itself either as pleasurable or painful. No state of consciousness can be wholly indifferent or have no value whatever for the self; though the perception of a tree, the hearing of a death of a friend, or the plan of building a house will have very different values.

Will. — A state of consciousness is also an expression of activity. As we shall see hereafter, there is no consciousness which does not depend upon the associating, and especially the attentive, activities of mind; and looked at in this way, every consciousness involves will, since in the perception of a tree, in the hearing of the death of a friend, or in the plan to build a house, the mind is engaged in action. It is never wholly passive in any consciousness. Yet it is evident that in the perception of the tree that factor of the consciousness is especially regarded which gives us information about something; in the death of a friend it is not with the fact of news nor with the mind’s activity that we are concerned, but with the way in which the mind, the self, is affected; while in the plan and execution of the plan of building a house it is especially with the activity of the mind as devoted to realizing or bringing about a certain intention, purpose, or end that we have to do. The first would, ordinarily, be called an act of knowledge, the second, a mode of emotion, and to the third would be restricted the term volition or will. Any state of consciousness is really knowledge, since it makes us aware of something; feeling, since it has a certain peculiar reference to ourselves, and will, since it is dependent upon some activity of ours; but concretely each is named from the one aspect which predominates.

Relations to Each Other. — Feeling, knowledge, and will are not to be regarded as three kinds of consciousness; nor are they three separable parts of the same consciousness. They are the three aspects which every consciousness presents, according to the light in which it is considered; whether as giving information, as affecting the self in a painful or pleasurable way, or as manifesting an activity of self. But there is still another connection. Just as in the organic body the process of digestion cannot go on without that of circulation, and both require respiration and nerve action, which in turn are dependent upon the other processes, so in the organic mind. Knowledge is not possible without feeling and will; and neither of these without the other two.

Dependence of Knowledge. — Take, for example, the perception of a tree or the learning of a proposition in geometry. It may seem at first as if the perception of a tree were a purely spontaneous act, which we had only to open our eyes to perform, but we shall see that it is something which has been learned. Indeed, we have only to notice an infant to discover that the perception of an object is a psychical act which has to be learned as much as the truth of geometry. What, then, is necessary for the apprehension of either act? First, feeling is necessary, for unless the mind were affected in some way by the object or the truth, unless it had some interest in them, it would never direct itself to them, would not pay attention to them, and they would not come within its sphere of knowledge at all.

They might exist, but they would have no existence for the mind, unless there were something in them which excited the mind. Knowledge depends on feeling. But, again, the feeling results in knowledge only because it calls forth the attention of the mind, and directs the mind to the thing or truth to be known; and this direction of the attention is an act of will. In the case of first learning the proposition of geometry, it is easy to see that the directing, controlling, concentrating activity of will is constantly required, and the apprehension of the tree differs only in that there attention is automatically and spontaneously called forth, according to principles to be studied hereafter.

Dependence of Volition. — An act of will involves knowledge. It may be a comparatively simple act, like writing, or a complex one, like directing some great business operation. In either case there is required a definite idea of the end to be reached, and of the various means which are requisite for reaching it; knowledge of the result aimed at and of the processes involved in bringing it about are necessary for the execution of any volition. But there is also a dependence upon feeling. Only that will be made an object of volition which is desired, and only that will be desired which stands in some relation to self. The purely uninteresting or colorless object, that which has not emotional connections, is never made an end of action. It is a mere truism to say that one never acts except for that which he believes to be of some importance, however slight, and this element of importance, of value, is always constituted by reference to self, by feeling.

Dependence of Feeling. — Feeling, on the other hand, presupposes volition. Where there is no excitation, no stimulation, no action, there is no feeling. When we study feeling in detail we shall find that pleasurable feeling is always an accompaniment of healthy or of customary action, and unpleasant feeling the reverse. It is enough to notice now that feeling is the reference of any content of consciousness to self, and that the self is only as it acts or reacts. Without action or reaction there is, therefore, no feeling. If we inquire into the pleasure which arises from the acquisition of money, or the pain which comes from the loss of a friend, we shall find that one furthers and assists certain modes of activity which are in some way identified with the self, while the other hinders them, or wholly destroys them. One, in short, develops the self; the other reduces it. The activity of the self, either in raising or lowering the level of its activity, expresses itself in feeling.

All concrete, definite forms of feeling depend also upon the intellectual activities. We find our feelings clustering about objects and events; we find them associated with the forms of knowledge, and just in the degree in which they are thus associated do they cease to be vague and undefinable. Even in the lowest forms of emotional consciousness, as the pleasure of eating, or the pain of a bruise, we find some reference to an object. The feeling is not left floating, as it were, but is connected with some object as its cause, or is localized in some part of the organism. The higher and more developed the feeling, the more complete and definite is the connection with the intellectual sphere. The emotions connected with art, with morals, with scientific investigation, with religion, are incomprehensible without constant reference to the objects with which they are concerned.

Necessary Connection with Each Other. — We have now seen that will, knowledge, and feeling are not three kinds of consciousness, but three aspects of the same consciousness. We have also seen that each of these aspects is the result of an artificial analysis, since, in any concrete case, each presupposes the other, and cannot exist without it. The necessity of this mutual connection may be realized by reverting to our definition of psychology, where it was said that psychology is the science of the reproduction of some universal content in the form of individual consciousness. Every consciousness, in other words, is the relation of a universal and an individual element, and cannot be understood without either. It will now be evident that the universal element is knowledge, the individual is feeling, while the relation which connects them into one concrete content is will. It will also be seen that knowledge and feeling are partial aspects of the self, and hence more or less abstract, while will is complete, comprehending both aspects. We will take up each of these points briefly.

Knowledge as Universal. — We have already seen that the subject-matter of knowledge is universal; that is to say, it is common to all intelligences. What one knows every one else may know. In knowledge alone there is no ground for distinction between persons. Were individuals knowing individuals only, no one would recognize his unique distinctness as an individual. All know the same, and hence, merely as knowing, are the same. But feeling makes an inseparable barrier between one and other.

Two individuals might conceivably have feelings produced by the same cause, and of just the same quality and intensity, in short, exactly like each other, and yet they would not be the same feeling. They would be absolutely different feelings, for one would be referred to one self, another to another. It is for this reason, also, that as matter of fact we connect knowledge with ourselves as individuals. In any actual ease knowledge has some emotional coloring, and hence is conceived as being one’s own knowledge. Just in the degree in which this emotional coloring is absent, as in the perception of a tree or recognition of a truth of mathematics, the consciousness is separated from one’s individual self, and projected into a universe common to all. Individuality of consciousness means feeling; universality of consciousness means knowledge.

Will as the Complete Activity. — The concrete consciousness, on the other hand, including both the individual and the universal elements, is will. Will always manifests itself either by going out to some universal element and bringing it into relation to self, into individual form, or by taking some content which is individual and giving it existence recognizable by all intelligences. The knowledge of a tree or recognition of the truth of geometry illustrate the first form. Here material which exists as common material for all consciousness is brought into relation with the unique, unsharable consciousness of one. The activity of will starts from the interests of the self, goes out in the form of attention to the object, and translates it into the medium of my or your consciousness — into terms of self, or feeling. If we consider this activity in the value which it has as manifesting to us something of the nature of the universe, it is knowledge; if we consider it in the value which it has in the development of the self, it is feeling; if we consider it as an activity, including both the universal element which is its content, and the individual from which it starts and to which it returns, it is will. This we may call incoming will, for its principal phase is that in which it takes some portion of the universe and brings it into individual consciousness, or into the realm of feeling.

Out-going Will. — The other form of will is that which starts from some individual consciousness and gives it existence in the universe. The first stage is a desire, a plan, or a purpose; and these exist only in my or your consciousness, they are feelings. But the activity of self takes hold of these, and projects them into external existence, and makes them a part of the world of objects and events. If the desire be to eat, that is something which belongs wholly to the individual; the act of eating is potentially present to all intelligences; it is one of the events that happen in the world. If the purpose be to obtain riches, that, again, is a purely individual consciousness; but the activities which procure these riches are universal in nature, for they are as present to the intelligence of one as another. If the plan be to build a house, the plan formed is individual; the plan executed, the house built, is universal. This act of will resulting in rendering an individual content universal may be called out-going will, but its essence is the same as that of in-coming will. It connects the two elements which, taken in their separateness, we call feeling and knowledge.

The Subjective and Objective. — Feeling is the subjective side of consciousness, knowledge its objective side. Will is the relation between the subjective and the objective. Every concrete consciousness is this connection between the individual as subjective, and the universe as objective. Suppose the consciousness to be that arising from a cut of a finger. The pain is purely subjective; it belongs to the self pained and can be shared by no other. The cut is an objective fact; something which may be present to the senses of all, and apprehended by their intelligences. It is one object amid the world of objects. Or, let the consciousness be that of the death of a friend. This has one side which connects it uniquely with the individual; it has a certain value for him as a person, without any reference to its bearings as an event which has happened objectively. It is subjective feeling. But it also is an event which has happened in the sphere of objects; something present in the same way to all. It is objective; material of information. Will always serves to connect the subjective and the objective sides, just as it connects the individual and the universal.

The student must, at the outset, learn to avoid regarding consciousness as something purely subjective or individual, which in some way deals with and reports a world of objects outside of consciousness. Speaking from the standpoint of psychology, consciousness is always both subjective and objective, both individual and universal. We may artificially analyze, and call one side feeling and the other knowledge, but this is an analysis of consciousness; it is not a separation of consciousness from something which is not in consciousness. For psychology no such separation can possibly exist.

Method of Treatment. — In treating the material of psychology it is necessary, for purposes of presentation, to regard the separation of feeling from knowledge, and both from will, as more complete and rigid than it can be as matter of actual fact. Each will be considered separately, as if it were an independent, self-sufficient department of the mind. It might seem most logical to begin this treatment with feeling, as that is the most intimate, internal side of consciousness, but the dependence of the definite forms of feeling upon the definite forms of knowledge is so close that this is practically impossible. The dependence of knowledge upon feeling is, however, a general, not a specific one; so the subject of knowledge can be treated with only a general reference to feeling. Will, as pre supposing both knowledge and feeling, will be treated last.

Material and Processes. — In treating each of these heads we shall also, for purposes of clear presentation, subdivide the subject into three topics: (l) material, (2) processes, (3) results. That is to say, the object of the science of psychology is to take the concrete manifestations of mind, to analyze them and to explain them by connecting them with each other. “We shall regard the existing states as the result of the action of certain processes upon a certain raw material. We shall consider, first, the raw material; second, the processes by which this raw material is worked up or elaborated; and third, the concrete forms of consciousness, the actual ideas, emotions, and volitions which result from this elaboration. The first two accordingly correspond to nothing which has separate independent existence, but are the result of scientific analysis. The actual existence is, in all cases, the third element only, that of result. Beginning, therefore, with knowledge, we shall define sensation as its raw material, consider the process of apperception, which elaborates this material into the successive stages of perception, memory, imagination, thinking, and intuition, finally recognizing that the concrete intellectual act is always one of intuition.

PART I. KNOWLEDGE.

CHAPTER III. ELEMENTS OF KNOWLEDGE.

§ 1. Sensation in General.

SENSATION IDENTIFIED. — However great the difficulties connected with sensation, it is the easiest of all mental phenomena to identify. The feeling of warmth, of pressure, the hearing of a noise, the seeing of a color — such states as these are sensations. In reference to its bodily conditions, also, a sensation is easily defined: it is any psychical condition whose sole characteristic antecedent is a stimulation of some peripheral nerve structure. Thus, we refer the getting of sensations of warmth and pressure to some organs in the skin; noise to the ear; color to the eye, etc.”

Treatment of Subject. — A sensation is thus seen to involve two elements — a physical and a psychical. It is concerned, on the one hand, with the body; on the other with the soul. The physical factor may be considered with reference either to the stimulus which affects the nerve organ, or with relation to the nerve activity itself. We shall consider, accordingly, the following topics under the head of sensation: I. The physical stimulus in its broad sense, including subdivisions into the extra-organic stimulus and the physiological.

II. The psychical element, or sensation proper. III. The relation between the physical and the psychical factors. IV. The function of sensation in intellectual life.

I. THE PHYSICAL STIMULUS.

1. Extra-organic Stimulus. — While a few of our sensations arise from operations going on within our own body, the larger number, and those most important in their cognitive aspect, originate in affections of the organism by something external to it. Things just about us affect the organs of touch; bodies still more remote impinge upon us through the sense of hearing, while in vision almost no limit is put to the distance from which bodies may affect us through light. But numerous as seem the various ways in which external bodies may affect us, it is found that these various modes are reducible to one — motion. Whether a body is near or far, the only way in which it affects the organism so as to occasion sensation is through motion. The motion may be of the whole mass, as when something hits us; it may be in the inner particles of the thing, as when we taste or smell it; it may be a movement originated by the body and propagated to us through vibrations of a medium, as when we hear or see. But some form of motion there must be. An absolutely motionless body would not give rise to any affection of the body such as ultimately results in sensation.

Characteristics of Motion. — Accordingly it is not the mere thing, but the thing with the characteristic of motion, that is the extra-organic stimulus of sensation. For psychological purposes, the world may be here regarded, not as a world of things with an indefinite number of qualities, but as a world of motions alone.

The world of motion, however, possesses within itself various differences, to which the general properties of sensations correspond. Movements are not all of the same intensity, form, or rapidity. Put positively, motion possesses amplitude, form, and velocity. Amplitude is the extent to and fro, up and down, of the movement. It is the length of its swing, or the distance which the body moves from a point of rest. The body may move through this distance in the thousandth of a second, or in a second. This rate at which a body moves constitutes its velocity. Again, the motion may be regular or vibratory, or irregular. Amid the regular movements there may be further differences of form. It may be circular, elliptic, or parabolic. It may be a movement like that of a pendulum, a piston, or a trip-hammer.

Characteristics of Sensations. — The differences which exist in sensations correspond to these differences in stimuli. To the amplitude of the motion agrees, in a general way, the intensity of the sensation. The wider the swing of the body the greater the force with which it will impinge upon the sense organ, and the stronger the resulting sensation. To differences of form correspond differences in quality. Stimuli which are irregular seem to occasion the vaguer, confused sensations, like those of taste and smell; the higher, of hearing and sight, being produced by regular vibrations. Within the sphere of sounds, the differences between noises and musical tones seem to correspond to this distinction of stimuli. Finally, vibrations of a low rate of velocity (below twenty per second) affect us through the sense of contact as a feeling of jar; from nineteen to about forty thousand per second we have affections of sound; to the various rates of which correspond those specific differences of sensation known as pitch. Above this rate the vibrations are too numerous to be responded to by the auditory apparatus, and we have a sharp feeling of whizzing. When the vibrations reach the enormous number of three hundred and ninety-two billions per second we begin to have color sensations, at this rate, of red; and these continue up to seven hundred and eighty-five billions, when violet finishes. Between these velocities lies the scale of colors. Above their highest rate the eye does not distinguish light, and we have the motions which produce the so-called actinic effects most largely.

Classes of Extra-organic Stimuli. — These may be divided into general and special. Certain forms of motion, as mechanical pressure, heat, and electricity, affect all sensory organs alike. Any one of them, if applied to the ear, occasions sound; to the eye, light, etc. The motions which are termed special are peculiarly adapted to some one sense organ, which alone is fitted to respond to them. Waves of ether awaken no consciousness within us except as they impinge upon the retina of the eye. Waves of air find an especially responsive medium in the ear, while certain chemical actions, not understood, have special reference to the nerves of smell and taste.

2. The Physiological Stimulus. — No sensation exists as yet. The external stimulus is but the first prerequisite. It is a condition which in many cases may be omitted, as when the stimulus arises within the body itself. Its function is exhausted when the nerve is aroused to activity. It must be transformed into a physiological motion before any sensation arises. The mode of transformation has given rise to a division of the senses into mechanical and chemical. In some cases the physiological stimulus appears as a continuation of the external. Thus the extra-organic stimuli occasioning pressure undergo no decided alteration upon affecting the organs of touch; it is highly probable that the auditory nerve continues the stimulus without chemical change. But in taste and smell there is evidently a chemical transformation. The sapid or odorous substance sets up some chemical process in the nerve endings, and the stimulus reaches the brain in a different form from that originally affecting the sensory organ. In vision both mechanical and chemical activities seem to be combined.

Stages of the Physiological Stimulus. — Here three stages may be distinguished: first, the excitation of the peripheral organ; second, the conduction of the excitement thus produced along the nerve fibre to the brain; and, third, the reception of and reaction upon the transmitted stimulus by the brain. There is change in the organ, change in the nerve, change in the brain. Subject to a qualification hereafter to be made, the integrity of each of these elements is necessary for a sensation.

Specific Nerve Energy. — Regarding the method of the reaction of the nerve organs upon the extra-organic stimulus which tranforms it into a physiological one, it may be said that each nerve organ responds to all stimuli, of whatever kind, in the same way. The mind, for example, always answers sound to all calls made upon the ear, whether these calls be made by way of pressure, electricity, or the more ordinary one of vibrations of air. In the same way the mind always reacts with a sensation of light to every excitation of the eye, whether made by etheric vibration or mechanical pressure and irritation. This is the fact known as specific nerve energy; whether it is due to the original structure of the nervous organism, or is the result of adaptation through constant use in one way, is disputed. Of the fact itself there is no doubt.

Vicarious Brain Action. — It was mentioned that the statement regarding the necessity of integrity of brain, nerve, and sense organ for the production of a sensation would require qualification. It is found that when the connection between the sense organ and the brain has once been thoroughly formed the latter tends to have its structure altered in such a way that, in abnormal and unusual cases, nervous changes going on within it may take the place of that usually occurring in the organ and nerves. People who have become blind in adult life do not lose their power of imagining visual forms and color. Their appreciation of these is as real, though internal, as that of the person who has his eye affected by the physical stimulus of light.

Persons who have lost an arm or a leg still seem to feel in the amputated part. They continue to refer sensations to the absent member. In certain abnormal states, as in fevers, etc., sensations arise within the brain itself of such force and vividness as to occasion utterly erroneous ideas about the external world. When no affection of the nerve organ exists sounds are heard, lights appear, wonderful and strange scenes, to which nothing objective corresponds, pass before the vision. It is hardly possible to account for the phenomena of dreams, except upon the theory that every excitation of the brain is not due to an immediately antecedent excitation of a sense organ, but may spontaneously be called forth in the brain itself. These various facts lead to the supposition that the activity in the brain may be self-induced, under certain circumstances, having the same psychical result as would the more regular excitation through peripheral organs and sensory nerves, and that, consequently, the ultimate element with which the mind has to deal is the change in the brain alone.

II. THE PSYCHICAL FACTOR.

Sensation as Consciousness. — We have as yet no sensation. A sensation is psychical; it is a consciousness; it not only exists, but it exists for the self. The changes in the nervous system, including the brain, are purely physical; they are objective only, and have no conscious existence for themselves. They exist in consciousness only as brought into the mind of some spectator. The relations between the two processes, the objective stimulus of motion and the subjective response of consciousness, we shall study hereafter. At present we are concerned with finding out what are the essential traits of a sensation considered as an element in consciousness.