2,73 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Delphi Classics

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Masters of Art

- Sprache: Englisch

The genius of Leonardo da Vinci epitomises, more than that of any other figure, the Renaissance humanist ideal. The Italian painter, draftsman, sculptor, architect and engineer produced some of the most influential masterpieces of Western art, which remain the most widely popular and influential paintings of the Renaissance. Leonardo’s notebooks reveal a spirit of scientific inquiry and a mechanical inventiveness that were quite simply centuries ahead of their time. Delphi’s ‘Masters of Art’ series allows digital readers to explore the works of the world’s greatest artists in comprehensive detail. This volume presents the complete works of Leonardo da Vinci, the world's greatest painter, in beautiful detail, with concise introductions and the usual Delphi bonus material. (Version 2)

Features:* The complete paintings of Leonardo da Vinci

* Includes previously lost works, with annotations

* Concise introductions to the paintings and other works, giving valuable contextual information

* Learn the secrets of the MONA LISA, the history of THE LAST SUPPER and the meaning behind THE VITRUVIAN MAN

* Includes Leonardo’s drawings and his complete notebooks, with plates

* Special criticism section, with essays by critics such as Sigmund Freud

* Features two biographies on Leonardo's life, including Vasari's famous biography

* Enlarged ‘Detail’ images, allowing you to explore Leonardo’ celebrated works in detail, as featured in traditional art books

* Hundreds of images in stunning colour – highly recommended for viewing on tablets and smart phones or as a valuable reference tool on more conventional eReaders

* Easily locate the paintings you want to view

* Scholarly ordering of plates into chronological order

* UPDATED with improved images and recently attributed works Please visit: www.delphiclassics.com to browse our range of art eBooks CONTENTS: The Paintings

TOBIAS AND THE ANGEL

MADONNA OF THE POMEGRANATE

THE MADONNA OF THE CARNATION

THE BAPTISM OF CHRIST

THE ANNUNCIATION

THE BENOIS MADONNA

PORTRAIT OF GINEVRA DE’ BENCI

ST. JEROME IN THE WILDERNESS

THE ADORATION OF THE MAGI

THE VIRGIN OF THE ROCKS (LOUVRE)

THE VIRGIN OF THE ROCKS (NATIONAL GALLERY)

THE HEAD OF A WOMAN

LITTA MADONNA

LADY WITH AN ERMINE

PORTRAIT OF A MUSICIAN

LA BELLE FERRONNIÈRE

THE LAST SUPPER

THE MADONNA OF THE YARNWINDER

MONA LISA

THE VIRGIN AND CHILD WITH ST. ANNE

LEDA AND THE SWAN

ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST

BACCHUS (ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST)

THE BATTLE OF ANGHIARI

SALVATOR MUNDI

PORTRAIT OF A LADY IN PROFILE

MADONNA AND CHILD WITH ST. JOSEPH The Drawings

THE VITRUVIAN MAN

THE VIRGIN AND CHILD WITH ST. ANNE AND ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST

SELF-PORTRAIT

STUDY OF HORSES

OTHER DRAWINGS The Notebooks

THE NOTEBOOKS OF LEONARDO DA VINCI

THOUGHTS ON ART AND LIFE The Criticism

LEONARDO DA VINCI by Sigmund Freud

Extract from ‘THE RENAISSANCE’ by Walter Pater

Extract from ‘ESSAYS ON ART’ by A. Clutton-Brock The Biographies

LIFE OF LEONARDO DA VINCI by Giorgio Vasari

LEONARDO DA VINCI by MAURICE W. BROCKWELL Please visit www.delphiclassics.com to browse through our range of exciting titles or to buy the whole Art series as a Super Set

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 1779

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Leonardo da Vinci

(1452-1519)

Contents

The Paintings

Tobias and the Angel

Madonna of the Pomegranate

The Madonna of the Carnation

The Baptism of Christ

The Annunciation

The Benois Madonna

Portrait of Ginevra De’ Benci

St. Jerome in the Wilderness

The Adoration of the Magi

The Virgin of the Rocks (Louvre)

The Virgin of the Rocks (National Gallery)

The Head of a Woman

Litta Madonna

Lady with an Ermine

Portrait of a Musician

La Belle Ferronnière

The Last Supper

The Madonna of the Yarnwinder

Mona Lisa

The Virgin and Child with St. Anne

Leda and the Swan

St. John the Baptist

Bacchus (St. John the Baptist)

The Battle of Anghiari

Salvator Mundi

Portrait of a Lady in Profile

Madonna and Child with St. Joseph

The Drawings

The Vitruvian Man

The Virgin and Child with St. Anne and St. John the Baptist

Self-Portrait

Study of Horses

Other Drawings

The Notebooks

The Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci

Thoughts on Art and Life

The Criticism

Leonardo Da Vinci by Sigmund Freud

Extract from ‘The Renaissance’ by Walter Pater

Extract from ‘Essays on Art’ by A. Clutton-Brock

The Biographies

Life of Leonardo Da Vinci by Giorgio Vasari

Leonardo Da Vinci by Maurice W. Brockwell

The Delphi Classics Catalogue

© Delphi Classics 2014

Version 2

Browse our Art eBooks…

Browse the Masters of Art Series

Masters of Art Series

Leonardo da Vinci

By Delphi Classics, 2014

COPYRIGHT

Masters of Art - Leonardo Da Vinci

First published in the United Kingdom in 2014 by Delphi Classics.

© Delphi Classics, 2014.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: [email protected]

www.delphiclassics.com

Interested in Renaissance literature and art?

Then you’ll love these eBooks…

Explore Renaissance eBooks

Enjoying our Art series of eBooks? Then try our Classical Music series:

A first of its kind in digital print, the Delphi Great Composers series allows digital readers to explore the works of the world’s greatest composers in comprehensive detail, with interactive links to popular streaming services.

Explore the series so far…

The Paintings

Vinci, a town in Tuscany — the birthplace of the world’s most famous painter

Leonardo’s childhood home in Anchiano, close to his birthplace town of Vinci

Tobias and the Angel

Leonardo was born on 15 April 1452 in the Tuscan hill town of Vinci, in the lower valley of the Arno river, then part of the Medici-ruled Republic of Florence. He was the out-of-wedlock son of the wealthy Florentine legal notary Messer Piero Fruosino di Antonio da Vinci and Caterina, a peasant girl. Little is known about the artist’s early life. He spent his first five years in the hamlet of Anchiano in the home of his mother, and from 1457 he lived in the household of his father, grandparents and uncle in Vinci. His father had married a sixteen-year-old girl named Albiera Amadori, who loved Leonardo, but died young in 1465 without children.

Receiving an informal education in Latin, geometry and mathematics, Leonardo recorded only two childhood incidents of note. One, which he regarded as an omen, was when a kite dropped from the sky and hovered over his cradle, its tail feathers brushing his face. The second event occurred while he was exploring in the mountains and discovered a cave; he was terrified that a great monster might lurk there, though he was also driven by curiosity to find out what was inside.

Leonardo’s early life continues to fuel historical conjecture. Vasari, the sixteenth century biographer of Renaissance painters, tells a story of Leonardo as a very young man. A local peasant made himself a round shield and requested that Ser Piero have it painted for him. Leonardo responded with a painting of a monster spitting fire that was so frightening that Ser Piero sold it to a Florentine art dealer, who in turn sold it to the Duke of Milan. Meanwhile, having made a profit, Ser Piero bought a shield decorated with a heart pierced by an arrow, which he gave to the peasant.

In 1466, at the age of fourteen, Leonardo was apprenticed to the leading Florentine painter and sculptor of his day, Verrocchio, whose workshop was one of the finest in Florence. Apprenticed as a garzone (studio boy), Leonardo remained working under Verrocchio for seven years. Other famous painters apprenticed or associated with the workshop include Domenico Ghirlandaio, Perugino, Botticelli and Lorenzo di Credi. Therefore, the young Leonardo would have been exposed to both theoretical training and a vast range of technical skills, including drafting, chemistry, metallurgy, metal working, plaster casting, leather working, mechanics and carpentry, as well as the artistic skills of drawing, painting, sculpting and modelling.

Completed by 1480, the altar painting Tobias and the Angel is attributed to the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio and is now housed in the London National Gallery. Some art historians believe that Leonardo, who was a member of Verrocchio’s studio at the time, had painted some of the work, most likely the fish. David Alan Brown, of the National Gallery in Washington, attributes the painting of the little dog to Leonardo as well. If these scholars are correct, then this would be the first extant painting of the renowned artist.

Theimage depicts a scene from the Book of Tobit, in which Tobias, son of Tobit, meets the angel Raphael, without realising his true identity. Tobias had been sent by his father to collect a sum of money that the latter had deposited some time previously in the distant land of Media. According to the story, Raphael represented himself as Tobit’s kinsman Azariah, and offered to aid and protect Tobias on his journey. Under the guidance of Raphael, Tobias made the journey to Media, accompanied by his faithful dog. Along the way, when washing his feet in the river Tigris, Tobias was attacked by a fish that tried to swallow his foot. Under the instructions of the angel he seized it and removed the heart, liver and gall bladder to make a special medicine. Raphael then told the young man how the fish could be used to cure Tobias’ cousin, a young woman named Sarah, who was plagued by the demon of lust. Asmodeus, ‘the worst of demons’ had previously abducted and killed every man she married. Through the angel’s aid, Tobias was successful in driving the demon away from his cousin and the two were speedily married.

Detail

Detail

Detail of Archangel Raphael — some scholars claim Leonardo was a model for this subject

Madonna of the Pomegranate

Also known as The Dreyfus Madonna, the Madonna of the Pomegranate has been attributed to Verrocchio and Lorenzo di Credi, as well as Leonardo. The anatomy of the Christ Child is so poor as to discourage firm attribution by most critics, while some believe that it is a work of Leonardo’s youth. This attribution was made by Suida in 1929. Other art historians, such as Shearman and Morelli, attribute the work to Verrocchio.

Detail

Detail

The Madonna of the Carnation

This oil painting was completed by 1480 and is permanently displayed at the Alte Pinakothek gallery in Munich. The central subject is the young Virgin Mary with Baby Jesus on her lap. Mary is seated and wears precious clothes and jewellery. With her left hand, she is holding a carnation, which has been interpreted as a healing symbol. Originally this painting was thought to have been created by Andrea del Verrocchio, but art historians now tend to agree it is Leonardo’s work. The canvas is the only work by Leonardo that is permanently on display in Germany.

Detail

Detail

Detail

Detail

The Baptism of Christ

This painting was finished circa 1475 in the studio of the painter Andrea del Verrocchio and the work is now generally ascribed to him and his young pupil Leonardo. Some art historians believe that other members of Verrocchio’s workshop had a hand in the painting as well. The picture depicts the Baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist as recorded in the Biblical Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke. The angel to the left is recorded as having been painted by Leonardo. The work is now permanently housed in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

Commissioned by the Church of S. Salvi, the painting was later transferred to the Vallumbrosan Sisterhood in Santa Verdiana. In 1810 the work entered the collection of the Accademia and passed to the Uffizi in 1959. In the 16th century the work was discussed in Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Painters in the biographies of both Verrocchio and Leonardo da Vinci.

Detail

Detail

Detail

The Annunciation

Painted by Leonardo and Andrea del Verrocchio, this work dates from circa 1472–1475 and is now housed in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. The painting portrays an angel holding a Madonna lily, a symbol of Mary’s virginity and of the city of Florence. It is supposed that Leonardo originally copied the wings from those of a bird in flight, but they have since been altered and lengthened by a later artist

When TheAnnunciation came to the Uffizi in 1867 from the Olivetan monastery of San Bartolomeo, it was ascribed to Domenico Ghirlandaio, who was also an apprentice to Andrea del Verrocchio. In 1869, Karl Eduard von Liphart, the central figure of the German expatriate art colony in Florence, recognised it as an early work by Leonardo, one of the first attributions of a surviving work to the artist. When the Annunciation was x-rayed, Verrocchio’s work was clearly evident, while Leonardo’s angel was invisible.

Detail

The angel’s wings were inspired by real life birds’ feathers, a technique unprecedented in Western art

Detail

The Benois Madonna

It is believed that this is the first independent work painted by Leonardo, when no longer under the direct tutelage of his master Verrocchio. There are two of Leonardo’s preliminary sketches for this piece in the British Museum, as the composition of a Madonna and Child proved to be one of Leonardo’s most popular subjects. This work was extensively copied by young painters, including Raphael, whose own version The Madonna of the Pinks reveals Leonardo’s influence on the younger artist.

For centuries, The Benois Madonna was considered lost. In 1909, the architect Leon Benois sensationally exhibited it in St Petersburg as part of his father-in-law’s collection. The painting had been apparently brought from Italy to Russia by the notable connoisseur Alexander Korsakov in the 1790s. Upon Korsakov’s death, it was sold by his son to the Astrakhan merchant Sapozhnikov for 1400 roubles and so passed by inheritance to the Benois family in 1880. After many disagreements regarding attribution, Leon Benois sold the painting to the Imperial Hermitage Museum in 1914. Since then, it has been housed in St. Petersburg.

Detail

Detail

Detail

Detail

Portrait of Ginevra De’ Benci

Ginerva De’ Benci was a Florentine aristocrat, admired for her intelligence by her contemporaries and immortalised in this famous portrait. The oil-on-wood painting was acquired by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., in 1967, for $5 million, paid to the Princely House of Liechtenstein, a record price at the time. Currently, it is the only painting by Leonardo in the Americas.

It is known that Leonardo painted a portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci in 1474, possibly to commemorate her marriage that year to Luigi di Bernardo Niccolini at the age of 16. However, according to Giorgio Vasari, Ginevra was not the daughter of Amerigo de’ Benci but his wife. The painting’s imagery and the text on the reverse of the panel support the identification of this picture. Directly behind the young lady in the portrait is a juniper tree, serving as an amusing play upon her name. The reverse of the portrait is decorated with a juniper sprig encircled by a wreath of laurel and palm and is inscribed with the phrase VIRTUTEM FORMA DECORAT (‘beauty adorns virtue’).

The reverse of the portrait

Detail

Detail

St. Jerome in the Wilderness

Begun in 1480, this is an unfinished work, now housed in the Vatican Museums, Rome. The canvas depicts St. Jerome during his retreat to the Syrian desert, where he lived the life of a hermit. The saint kneels in a rocky landscape, gazing toward a crucifix, which can be discerned faintly sketched in at the extreme right of the painting. In Jerome’s right hand he holds a rock with which he is traditionally shown beating his chest in penance. At his feet is the lion that became his loyal companion after he extracted a thorn from its paw. The lion, the stone and a cardinal’s hat are the traditional attributes of the saint. To the right-hand side, the only discernible feature is a faintly-sketched church, seen through the opening in the rocks. The church’s presence may allude to Jerome’s position in Western Christianity as one of the Doctors of the Church.

The composition of the painting is innovative due to the trapezoid form of the saint’s figure. The angular forms contrast with the sinuous outline of the lion, which transcribes an “S” across the bottom of the painting. Interestingly, the form of St. Jerome prefigures that of the Virgin Mary in the famous Madonna of the Rocks.

The panel has been reduced in size and the remaining part was cut in two at some point in its history and reassembled by the early 19th-century collector, Cardinal Fesch, the uncle of Napoleon Bonaparte. Popular legend claims that the Cardinal discovered the part of the panel with the saint’s torso being offered as a table-top in a shop in Rome. Many years later, he found another piece being used as a wedge for a shoemaker’s bench.

Detail

The Adoration of the Magi

Leonardo was given this commission by the Augustinian monks of San Donato a Scopeto in Florence, but he departed for Milan the following year, leaving the painting unfinished. It has been housed in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence since 1670.

In the canvas, the Virgin Mary and Child are depicted in the foreground and form a triangular shape with the Magi kneeling in adoration. Behind them is a semicircle of accompanying figures, including what may be a self-portrait of the young Leonardo (on the far right). In the background on the left is the ruin of a pagan building, on which several workmen can be seen, apparently repairing the structure. On the right are men on horseback fighting and a sketch of a rocky landscape.

The ruins are a possible reference to the Basilica of Maxentius, which, according to Medieval legend, the Romans claimed would stand until a virgin gave birth. It is supposed to have collapsed on the night of Christ’s birth, though in fact it was not built until a later date. The ruins dominate a preparatory perspective drawing by Leonardo, which also includes the fighting horsemen. The palm tree in the centre has associations with the Virgin Mary, partly due to the phrase: ‘You are stately as a palm tree’ from the Song of Solomon.

Detail: possible self-portrait

Detail

The Virgin of the Rocks (Louvre)

This is one of two paintings by Leonardo of the same subject, which are identical except for two significant details. The current painting is usually housed in the Louvre and the other is on display in the National Gallery, London. Both paintings depict the Madonna and Christ Child with the infant John the Baptist and an angel, in a rocky setting that gives the paintings their usual name. The significant compositional differences are in the gaze and right hand of the angel. There are many minor ways in which the works differ, including the colours, lighting, flora and the use of sfumato (the technique of softening lines).

The Louvre version is considered by most art historians to be the earlier of the two, dating from around 1483-1486. Most authorities agree that the work is entirely by Leonardo and it is 8cm taller than the London version. The first certain record of the painting was in 1625, when it was part of the French royal collection. It is generally accepted that this work was produced for a commission of 1483 in Milan. It is believed it was privately sold by Leonardo and the London version painted at a later date to fulfil the commission.

Detail

Detail

Detail

Detail

Detail

Detail

The Virgin of the Rocks (National Gallery)

Originally thought to have been partially painted by Leonardo’s assistants, recent studies by the National Gallery have revealed that this work may have been painted entirely by Leonardo. It was commissioned for the chapel of the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception, in the church of San Francesco Maggiore in Milan. It was sold by the church, very likely in 1781, and certainly by 1785, when it was bought by Gavin Hamilton, an English a painter and dealer, who took it to England. After passing through various collections, it was bought by the National Gallery in 1880.

In June 2005, the painting was examined by infra-red reflectogram. This imaging revealed a draft of a different painting beneath the visible one. The draft portrays a woman, probably kneeling, with her right hand outstretched and her left on her heart. Some researchers believe that the artist’s original intention was to paint an adoration of the infant Jesus. Many other pentimenti are also visible under x-ray or infra-red examination.

Detail

Detail

Detail

Left-hand wing of the altar piece, probably by Ambrogio de Predis

Right-hand wing of the altar piece, probably by Luini

The Head of a Woman

Also known as La Scapigliata, this painting dates from approximately 1500 and is housed in the Galleria Nazionale of Parma. The work was left unfinished and was mentioned for the first time in the House of Gonzaga collection in 1627. It is perhaps the same work that Ippolito Calandra, in 1531, had suggested to hang in the bedroom of Margaret Paleologa, wife of Federico II Gonzaga. In 1501, the marquesses wrote to Pietro Novellara asking if Leonardo could paint a Madonna for her privately.

Litta Madonna

Housed in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, this canvas is generally attributed to Leonardo, though some cite Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio as the artist. There are numerous replicas of the Litta Madonna by other Renaissance painters and there is a preliminary sketch by Leonardo of the Madonna’s head in the Louvre.

The image depicts the Madonna nursing the infant Jesus, whose awkward posture has led some scholars to attribute parts of the painting to Leonardo’s pupil Boltraffio. Other clues that suggest Leonardo was not the only artist to have a hand in the painting are the harsh outlines of the Madonna and Child and the simplistic landscape.

This work was painted sometime in the 1480s for the Visconti rulers of Milan and soon passed to the Litta family, in whose possession it would remain for centuries. In 1865, Alexander II of Russia acquired the painting from Count Litta, the former minister to St. Petersburg and deposited the painting in the Hermitage Museum. The museum had the painting transferred from wood to canvas.

Detail

Detail

The preliminary sketch, housed in the Louvre

Lady with an Ermine

This painting was completed by 1490 and the subject of the portrait has been identified as Cecilia Gallerani, who was the mistress of Lodovico Sforza, Duke of Milan, to whom Leonardo was in service. The piece is housed in the Czartoryski Museum, Kraków, Poland and is cited in the museum’s guide as the first truly modern portrait. The portrait was painted in oils on a wooden panel, at a time when the medium of oil paint was relatively new to Italy. Leonardo was one of the first artists to adopt the new medium, skilfully exploiting its qualities to great effect. This work particularly demonstrates Leonardo’s expertise in depicting the human form. The outstretched hand of Cecilia was painted with great detail. Leonardo delineates every contour of each fingernail, each wrinkle around her knuckles and even the flexing of the tendon in her bent finger.

At the time of her portrait, Cecilia was about sixteen. She was one of a large family, neither rich nor noble. Her father served for a time at the Duke’s court. Cecilia was renowned for her beauty, her scholarship and her poetry. She was betrothed at the age of about ten years to a young nobleman of the house of Visconti, but the marriage was called off. Cecilia became the mistress of the Duke and bore him a son, though he chose to marry a girl from a nobler family, Beatrice d’Este.

The painting portrays a half-length figure, the body of the young woman turned at a three-quarter angle towards her right, with her face turned towards her left. Her gaze is directed neither straight ahead, nor towards the viewer, but points indirectly beyond the picture’s frame. In her arms Cecilia holds a small white-coated stoat, known as an ermine. Cecilia’s dress is comparatively simple, revealing that she is not a noblewoman. Her coiffure, known as a “coazone”, confines her hair smoothly to her head with two circlets of hair bound on either side of her face and a long plait at the back. Her hair is held in place by a fine gauze veil with a woven border of gold-wound threads, a black band and a sheath over the plait. There are several interpretations of the significance of the ermine in her portrait. The ermine, a stoat in its winter coat, was a traditional symbol of purity, as it was believed that an ermine would face death rather than soil its white coat.

Lady with an Ermine was acquired in Italy by Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski, the son of Princess Izabela Czartoryska and Prince Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski in 1798 and incorporated into the Czartoryskis’ family collections at Puławy in 1800. The inscription on the top-left hand corner of the painting, LA BELE FERIONIERE. LEONARD D’AWINCI., was probably added by a restorer shortly after its arrival in Poland and before the background was overpainted. The painting travelled extensively in the nineteenth century. For example, Princess Czartoryski rescued it in advance of the invading Russian army in 1830, then concealed the painting, sending it to Dresden and on to the Czartoryski place of exile in Paris, the Hôtel Lambert, finally returning it to Kraków in 1882. In 1939, almost immediately after the German occupation of Poland, it was seized by the Nazis and sent to the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin. In 1940 Hans Frank, the Governor General of Poland, requested that it be returned to Kraków, where it previously hung in his suite of offices. At the end of the Second World War, Lady with an Ermine was discovered by Allied troops in Frank’s country home in Bavaria. It has since returned to Poland and is once more on display at the Czartoryski Museum in Kraków.

Detail

Detail

Portrait of a Musician

This oil on wood painting has been attributed to Leonardo by some scholars and was probably painted in 1490. The subject of the painting was at one time thought to be Franchino Gaffurio, who was the maestro di cappella of the Milanese Cathedral. Although some believe it to be a portrait of Gaffurio, others think the subject of the portrait is the famous Leornardo da Pistoia of the court of Cosimo de’ Medici, painted after his discovery of the Corpus Hermeticus.

The musician is depicted holding a piece of paper, which is a musical score with notes written upon it. The man is positioned in a three-quarter position and he is staring at something outside the spectator’s field of vision. Compared to the detailed face of the musician, the red hat, his tunic and his hair seem to be the work of another painter. Art historians have conceded that the quality of the depiction of the young man’s face points towards Leonardo’s own composition, though the partition sheet and his hand may have been added by another artist.

Detail

La Belle Ferronnière

This portrait of a young woman is housed in the Louvre and is traditionally attributed to Leonardo. The painting’s title, applied as early as the seventeenth century, identifies the sitter as the wife or daughter of an ironmonger (a ferronnier). Some historians believe the title alludes to a reputed mistress of Francis I of France, who was married to a certain Le Ferron. According to a Romantic legend of revenge, the aggrieved husband Francis intentionally infected himself with syphilis, which he passed to the king through infecting his wife.

Detail

Detail

The Last Supper

This mural painting in Milan was created for Leonardo’s patron Duke Ludovico Sforza and his duchess Beatrice d’Este. It represents the scene of The Last Supper from the final days of Jesus as it is told in the Gospel of John 13:21, when Christ announces that one of his disciples will betray him. All twelve apostles display different reactions to the pronouncement, with various degrees of anger and shock.

The Last Supper measures 450 × 870 centimetres and covers an end wall of the dining hall at the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie. The subject of the work was a traditional choice for refectories, although the room was not a refectory at the time that Leonardo painted it. The main church building had only recently been completed, but was remodelled by Bramante, who was hired by Ludovico Sforza to build a Sforza family mausoleum. The mural was commissioned by Sforza to be the centrepiece of the mausoleum and so Leonardo began work on The Last Supper in 1495, completing the painting by 1498, though he did not work on it continuously.

In the image, Judas Iscariot, Peter and John form one group of three figures, with Judas wearing green and blue, whilst being depicted in shadow, looking withdrawn and taken aback by the sudden revelation of his secret. He is clutching a small bag, signifying the silver given to him as payment to betray Jesus or perhaps it is a reference to his role within the twelve disciples as the treasurer. He is also tipping over the salt shaker. This may be related to the near-Eastern expression to “betray the salt”, meaning to betray one’s Master. He is the only person to have his elbow on the table and his head is also horizontally the lowest of anyone in the work. Peter looks angry and is holding a knife pointed away from Christ, perhaps foreshadowing his violent reaction in Gethsemane during Jesus’ arrest. The youngest apostle, John, appears to swoon.

In common with other depictions of the subject from this period, Leonardo seats the diners on one side of the table, so that none of them have their backs to the viewer. Most previous depictions excluded Judas by placing him alone on the opposite side of the table from the others or placing halos around all the disciples, except for Judas. Leonardo instead depicts Judas as leaning back into shadow. Jesus is predicting that his betrayer will take the bread at the same time he does to Saints Thomas and James to his left, who react in horror as Jesus points with his left hand to a piece of bread before them. Distracted by the conversation between John and Peter, Judas reaches for a different piece of bread not noticing Jesus too stretching out with his right hand towards it. The angles and lighting draw attention to Jesus, whose head is located at the vanishing point of all perspective lines.

Leonardo painted The Last Supper on a dry wall rather than on wet plaster, so the work is not a true fresco. Since a fresco cannot be modified as the artist works, Leonardo instead chose to seal the stone wall with a layer of pitch, gesso and mastic, followed by paint on the sealing layer with tempera. Due to the method used, the piece began to deteriorate a few years after Leonardo finished the painting and it now appears somewhat unfinished. As early as 1517 the painting was starting to flake. By 1556, fewer than sixty years after it was finished, Leonardo’s biographer Giorgio Vasari described the painting as already “ruined” and so deteriorated that the figures were unrecognisable. In 1652 a doorway was cut through the (then unrecognisable) painting, and later bricked up. The doorway can still be seen as the irregular arch shaped structure near the centre base of the painting.

It is believed, from studying early copies, that Jesus’ feet were in a position symbolising the forthcoming crucifixion. In 1768 a curtain was hung over the painting for the purpose of protection; it instead trapped moisture on the surface, causing further damage. During World War II, on August 15, 1943, the refectory building was struck by a bomb. Though protective sandbagging prevented the painting from being struck by bomb splinters, it may have been damaged further by the vibration of the attack.

Detail — Judas on left, holding his pouch of coins

Detail

Christ at the centre

Santa Maria delle Grazie church and Dominican convent in Milan, which contains ‘The Last Supper’. The church is now one of Milan’s most popular tourist destinations, due to the fame of Leonardo’s mural.

This photo shows the bombing damage in 1943

The Madonna of the Yarnwinder

Created circa 1501, this is the subject of several oil paintings, of which the original version by Leonardo may now be lost. The composition depicts the Virgin Mary with the Christ child, who looks longingly at a yarnwinder used to gather spun yarn. The yarnwinder serves as a symbol of Mary’s domesticity and the Cross on which Christ would be crucified, as well as suggesting the Fates, who are known in classical mythology as spinners of fortune.

At least three versions of the painting are in private collections. The original painting was presumably commissioned by Florimund Robertet, the Secretary of State for King Louis XII of France. The version of this painting often regarded as the most likely to be by Leonardo is now in the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh, on loan from the Duke of Buccleuch. It hung in his home in Drumlanrig Castle, Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland until it was stolen in 2003 by two thieves posing as tourists. The painting was recovered at a lawyer’s office in Glasgow in October 2007 after police officers, from four anti-crime agencies, raided a meeting of five people. A spokesman for the law firm said: “There is absolutely no impropriety whatsoever. There is an interesting, but benign, explanation, but no wrongdoing has been done on their part.” Four arrests were made, including two solicitors from different firms. The Glasgow firm was reputed as being one of the country’s most successful and respected law firms, which claimed it was acting as a go-between for two parties to secure legal repatriation of the painting from an unidentified party. John Scott, 9th Duke of Buccleuch had died just a month before the recovery. Following its dramatic recovery, the painting has been loaned to the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh where it is currently on display.

Detail

Detail

A copy housed in a private collection in the US

Mona Lisa

This portrait is quite simply the most famous work of art in the world.Also known as La Gioconda, it was painted in oil on a poplar panel and completed by 1519. It is a half-length portrait, depicting a seated woman, Lisa del Giocondo, a member of the Gherardini family of Florence and the wife of a wealthy Florentine silk merchant. The painting was commissioned for their new home and to celebrate the birth of their second son. In the painting, the ambiguity of Lisa’s expression, the monumentality of the composition and the subtle handling of forms have all leant to the celebrity of this famous work of art, which is on permanent display at the Louvre in Paris

Leonardo began painting Mona Lisa in 1503 or 1504 in Florence, working occasionally on the piece for four years, before moving to France. He worked intermittently on the painting for another three years, finishing it shortly before he died in 1519. Most likely through the heirs of Leonardo’s assistant Salai, the king bought the painting for 4,000 écus and kept it at Château Fontainebleau, where it remained until given to Louis XIV, who moved it to the Palace of Versailles. After the French Revolution, it was relocated to the Louvre. Napoleon I had the portrait moved to his personal bedroom in the Tuileries Palace, but it was later returned to the Louvre.

Leonardo used a pyramid design to place his subject simply in the space of the painting. Her folded hands form the front corner of the pyramid. Her breast, neck and face glow in the same light that covers her hands. The light gives the different parts of her skin an underlying impression of life. The woman sits markedly upright with her arms folded, which is also a sign of her reserved posture. Her gaze seems to address us with a silent communication. The brightly lit face is practically framed with much darker elements, such as the sitter’s hair, veil and the surrounding shadows, contrasting strongly with the radiant quality of her face. The woman appears alive due to Leonardo’s use of sfumato, not drawing the outlines of the mouth and other parts of the face, but softening them instead with a smooth appearance.

The enigmatic Lisa is portrayed seated in what appears to be an open loggia, with dark pillar bases on either side. Behind her a vast landscape recedes to icy mountains. Winding paths and a distant bridge give only the slightest indications of human presence. The sensuous curves of the woman’s hair and clothing are echoed in the undulating imaginary valleys and rivers behind her. The blurred outlines, graceful figure, dramatic contrasts of light and dark, and overall feeling of calm are characteristic of the artist’s style. However, the landscape presented is in fact an ‘impossible’ landscape. The land on the right-hand side is much higher than the land on the left-hand side, which instead features a small lake. It has been argued that whilst a viewer switches their gaze between both sides of this ‘impossible’ landscape, it appears that the Mona Lisa moves or smiles, due to change of perspective.

The Mona Lisa was not well known until the mid-19th century, when artists of the emerging Symbolist movement began to appreciate the portrait, associating it with their ideas of feminine mystique. The portraitwas stolen on 21 August 1911 and the Louvre was closed for an entire week to aid the investigation of the theft. French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who had once called for the Louvre to be burnt down, was arrested and put in jail. Apollinaire tried to implicate his friend Pablo Picasso, who was also brought in for questioning, but both were later released and exonerated. At the time, the painting was believed to be lost forever, and it was two years before the real thief was discovered. Louvre employee Vincenzo Peruggia had stolen it by entering the building during regular hours, concealing himself in a broom closet and walking out with it hidden under his coat after the museum had closed. Peruggia was an Italian patriot, who believed Leonardo’s painting should be returned to Italy for display in an Italian museum. Peruggia may have also been motivated by a friend who sold copies of the painting, which would skyrocket in value after the theft of the original. After having kept the painting in his apartment for two years, Peruggia grew impatient and was finally caught when he attempted to sell it to the directors of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. The painting was exhibited all over Italy and returned to the Louvre in 1913. Peruggia was hailed for his patriotism in Italy and served only six months in jail for the crime.

In 1956, the lower part of the painting was severely damaged when a vandal doused the painting with acid. On 30 December of that same year, a young Bolivian named Ugo Ungaza Villegas damaged the painting by throwing a rock at it. This resulted in the loss of a speck of pigment near the left elbow, which was later painted over. The use of bulletproof glass has shielded the Mona Lisa from more recent attacks. In April 1974, a handicapped woman, upset by the museum’s policy for the disabled, sprayed red paint at the painting while it was on display at the Tokyo National Museum. On 2 August 2009, a Russian woman, distraught over being denied French citizenship, threw a terra cotta mug or teacup, purchased at the museum, at the painting in the Louvre. In both cases, the painting was undamaged.

Detail

Detail

Detail

Detail — left-hand landscape, featuring a small lake

The Isleworth Mona Lisa, housed in Switzerland in a private collection. Some claim that this is the earlier of two versions of the Mona Lisa, painted for Francesco del Giocondo in 1503, arguing that the Louvre version was painted for Giuliano de' Medici in 1517.

The Virgin and Child with St. Anne

This painting was commissioned as the high altarpiece for the Church of Santissima Annunziata in Florence and is now housed in the Louvre. It depicts St. Anne, her daughter the Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus. Christ is portrayed grappling with a sacrificial lamb, symbolising his Passion, as the Virgin attempts to restrain him. The Virgin Mother is sitting on St. Anne’s lap and it is unclear what meaning Leonardo intended with that pose. There is no clear parallel in other works of art of women sitting in each other’s lap.

Detail

Detail

Leda and the Swan

Leonardo began making studies in 1504 for a painting, apparently never executed, of the mythical Leda, the mortal mother of Helen of Troy, seated on the ground with her children. In 1508 he painted a different composition of the subject, with a nude standing Leda cuddling the Swan, with the two sets of infant twins and their huge broken egg-shells. The original of this is lost, probably deliberately destroyed, and was last recorded as being in the French royal Château de Fontainebleau in 1625 by Cassiano dal Pozzo. However, the work is known from many copies, of which the earliest is probably the Spiridon Leda, perhaps by a studio assistant and now housed in the Uffizi and the copy at Wilton House in Salisbury, England.

The Spiridon Leda, Uffizi Gallery, Florence

Detail

Detail

Another copy of Leonardo’s painting, housed in Wilton House

Detail

Detail

Another work inspired by Leonardo’s original lost painting — this time by Giampietrino

Detail

Detail

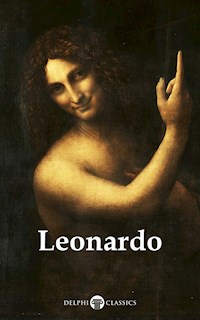

St. John the Baptist

Completed in 1516, when High Renaissance art was shifting into Mannerism, this painting is believed to be Leonardo’s last and is now housed in the Louvre. It depicts St. John the Baptist with long curly hair, alone in the dark and dressed in pelts. He bears an enigmatic smile, recalling once again the famous Mona Lisa. The saint holds a reed cross in his left hand, whilst his right hand points up towards heaven. It is believed that the cross and wool skins were added at a later date by another painter.

The pointing gesture of St. John toward the heavens suggests the importance of salvation through baptism, which this particular saint represents. The work produces an ambiguous and mysterious quality, as the gender of the subject appears uncertain and the smile on the saint’s face comes across as almost demonic, causing an eerie confusion in its intended meaning.

Detail

Detail

Detail

Bacchus (St. John the Baptist)

Housed in the Louvre, this painting is based on a drawing by Leonardo. It is presumed to have been executed by an unknown follower, perhaps in the artist’s workshop. The canvas depicts a male figure with a garlanded head and leopard skin, seated in an idyllic landscape. He points with his right hand off to his left, while with his left hand he grasps his thyrsus and points down to earth. The painting originally depicted John the Baptist, but in the late seventeenth century, it was altered to portray the mythical god Bacchus. The fur robe is the legacy of John the Baptist, but has been painted over with leopard-spots relating, like the wreath, to Bacchus, the Roman god of wine and revelry.

Detail

The Battle of Anghiari

This is the title of a lost painting by Leonardo. Its central scene depicted four men riding raging war horses engaged in a battle for possession of a standard at the Battle of Anghiari in 1440. Many preparatory studies by Leonardo still exist, but the work is best known through a drawing by the famous Dutch painter Peter Paul Rubens in the Louvre. Rubens’ drawing, dating from 1603, was based on an engraving of 1553 by Lorenzo Zacchia, which was taken from Leonardo’s painting itself or possibly derived from a cartoon by the artist.

In 1504 Leonardo was given the commission by Piero Soderini to decorate the Hall of Five Hundred. At the same time his rival Michelangelo, who had just finished his sculpture of David, was designated the opposite wall. This was the only time that Leonardo and Michelangelo worked together on the same project. The painting of Michelangelo depicted an episode from the Battle of Cascina, when a group of bathing soldiers was surprised by the enemy. However, Michelangelo did not stay in Florence long enough to complete the project. He was able to finish his cartoon, but only began the painting. He was invited back to Rome in 1505 by the newly appointed Pope Julius II and was commissioned to build the Pope’s tomb.

Leonardo drew his large cartoon in the Basilica di Santa Maria Novella, depicting a scene from the life of Niccolò Piccinino, a condottiere in the service of duke Filippo Maria Visconti of Milan. He drew a scene of a violent clash of horses and a furious skirmish of men fighting for the flag in the Battle of Anghiari. Giorgio Vasari praised the magisterial way Leonardo had put this scene on paper: “It would be impossible to express the inventiveness of Leonardo’s design for the soldiers’ uniforms, which he sketched in all their variety, or the crests of the helmets and other ornaments, not to mention the incredible skill he demonstrated in the shape and features of the horses, which Leonardo, better than any other master, created with their boldness, muscles and graceful beauty.”

Leonardo built an ingenious scaffold in the Hall of Five Hundred that could be raised or folded in the manner of an accordion. This painting was to be his largest and most substantial work. Since he had suffered an almost disastrous experience in fresco painting with The Last Supper, he wanted to apply oil colours on the wall. He began also to experiment with a thick undercoat, which after he applied the colours, the paint began to drip. Trying to dry the painting in a hurry and save whatever he could, he hung large charcoal braziers close to the painting. Only the lower part could be saved in an intact state. But the upper part did not dry fast enough and the colours intermingled. Leonardo then abandoned the project.

Michelangelo and Leonardo’s unfinished paintings adorned the same room together for almost a decade (1505-1512). The cartoon of Michelangelo’s painting was cut in pieces by Bartolommeo Bandinelli out of jealousy in 1512. The centrepiece of The Battle of Anghiari was greatly admired and numerous copies were made for decades.

In the mid-16th century (1555-1572), the hall was enlarged and restructured by Vasari and his helpers, so that Grand Duke Cosimo I could hold his court in the chamber. During this transformation, several famous, but unfinished works were lost, including The Battle of Cascina by Michelangelo and The Battle of Anghiari by Leonardo.

Rubens’ copy of ‘The Battle of Anghiari’

Detail

Detail

Detail

A drawing by Leonardo as a study for ‘The Battle of Anghiari’

Salvator Mundi

Long thought to be a copy of a lost original, this painting was restored in 2011, when it was rediscovered as a lost original work by Leonardo. It was then included in a major Leonardo exhibition at the National Gallery, London in 2011–12. Nevertheless, the attribution has been disputed by other specialists. The title translates as ‘Saviour of the World’ and depicts Christ giving a benediction with his right hand raised and two fingers extended. In his left hand, Christ holds a transparent rock crystal orb, signalling his role as saviour of the world and master of the cosmos — the 'crystalline sphere' of the heavens — as it was perceived during the Renaissance. Leonardo is believed to have painted the subject in France for Louis XII between 1506 and 1513.

The canvas was once owned by King Charles I and recorded in his art collection in 1649, before being auctioned by the son of the Duke of Buckingham in 1763. Salvator Mundi next appeared in 1900, damaged from previous restoration attempts and its authorship unclear, when it was purchased by a British collector, Sir Frederick Cook. Cook’s descendants sold the painting at auction in 1958 for £45. It was then acquired by a US consortium of art dealers in 2005, who authenticated the work as being by Leonardo. The painting was sold at auction by Christie’s in New York to Prince Bader bin Abdullah bin Mohammed bin Farhan al-Saud on behalf of the Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism on 15 November 2017, for $450.3 million, setting a new record for most expensive painting ever sold.

The former co-chairman of old master paintings at Christie's Nicholas Hall added his support to the claim of Leonardo authorship: “There is extraordinary consensus it is by Leonardo…this is the most important old master painting to have been sold at auction in my lifetime." Christie's listed the ways scholars had confirmed the attribution:

The reasons for the unusually uniform scholarly consensus that the painting is an autograph work by Leonardo are several, including the previously mentioned relationship of the painting to the two autograph preparatory drawings in Windsor Castle; its correspondence to the composition of the ‘Salvator Mundi’ documented in Wenceslaus Hollar’s etching of 1650; and its manifest superiority to the more than 20 known painted versions of the composition.

Furthermore, the extraordinary quality of the picture, especially evident in its best-preserved areas, and its close adherence in style to Leonardo’s known paintings from circa 1500, solidifies this consensus.

Detail

Detail

Detail

Detail

Detail

Louis XII (1462- 1515) by the workshop of Jean Perréal, c. 1514

The Louvre Abu Dhabi, Saadiyat Iceland, under construction, 2017. This museum will house the rediscovered painting.

Portrait of a Lady in Profile

Housed in the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan, this portrait is generally attributed to Ambrogio de Predis, though the face is thought by some to show the hand of Leonardo.

Detail

Madonna and Child with St. Joseph

This tempera on panel work, now housed in the Galleria Borghese in Rome, was previously attributed to Fra Bartolomeo. However, after recent cleaning, the Borghese Gallery sought attribution as a work of Leonardo's youth, based on the discovery of a fingerprint similar to one that appears in The Lady with the Ermine. The true identity of the artist is still unresolved.

The Drawings

Leonardo’s earliest known drawing, depicting the Arno Valley (1473), housed in the Uffizi, Florence

The Vitruvian Man

This famous drawing was created circa 1487, accompanied with notes based on the work of the famed architect Vitruvius. The drawing was made in pen and ink on paper, depicting a male figure in two superimposed positions with his arms and legs apart and simultaneously inscribed in a circle and square. The drawing and text are sometimes called the ‘Canon of Proportions’. Housed in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, it is only occasionally displayed. The drawing is based on the correlations of ideal human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise De Architectura. Vitruvius described the human figure as being the principal source of proportion among the Classical orders of architecture.

This image exemplifies the blend of art and science during the Renaissance and provides the perfect example of Leonardo’s keen interest in proportion. In addition, this picture represents a cornerstone of Leonardo’s attempts to relate man to nature.

Detail

The Virgin and Child with St. Anne and St. John the Baptist

Housed in the National Gallery, London, this drawing is believed to have been completed by 1500, drawn in charcoal and black and white chalk, on eight sheets of paper glued together. Due to its large size and format the drawing is presumed to be a cartoon for a painting, though no painting exists that is based directly on the cartoon.

The drawing depicts the Virgin Mary seated on the knees of her mother St. Anne and holding the Child Jesus, while St. John the Baptist, the cousin of Jesus, stands to the right. The drawing is notable for its complex composition, demonstrating the alternation in the positioning of figures that is first apparent in Leonardo’s paintings in the Benois Madonna. The knees of the two women point in different directions, with Mary’s knees turning out of the painting to the left, while her body turns sharply to the right, creating a sinuous movement. The knees and the feet of the figures establish a strong up-and-down rhythm at a point in the composition where a firm foundation comprising firmly planted feet, widely spread knees and a broad spread of enclosing garment would normally be found. While the lower halves of their bodies turn away, the faces of the two women turn towards each other, mirroring each other’s features. The delineation between the upper bodies has lost clarity, suggesting that the heads are part of the same body.

Detail

Self-Portrait

This drawing is widely accepted as a self-portrait of Leonardo, which he drew at approximately the age of 60. The portrait is drawn in red chalk on paper, depicting the head of an elderly man in three-quarter view, turned towards the viewer’s right. The subject is distinguished by his long hair and long waving beard, which flow over the shoulders and breast. The length of the hair and beard is uncommon in Renaissance portraits and suggests, as they still do now, a person of sagacity. The face has a somewhat aquiline nose and is marked by deep lines on the brow and pouches below the eyes. It appears as if the man has lost his upper front teeth, causing deepening of the grooves from the nostrils.

The drawing has been produced in fine lines, shadowed by hatching and executed with the left hand, as was Leonardo’s habit. The paper has brownish “fox marks” caused by the accumulation of iron salts, due to the build-up of moisture over time. The drawing is housed in the Royal Library in Turin and is not generally viewable by the public due to its fragility and poor condition.

Detail

Study of Horses

Leonardo was commissioned to create a statue of a horse in 1482 by the Duke of Milan Ludovico il Moro, but the work was never completed. It was intended to be the largest equestrian statue in the world, a monument to the Duke’s father Francesco. Leonardo did complete extensive preparatory work for the project, but he produced only a clay model, which was destroyed by French soldiers when they invaded Milan in 1499. About five centuries later, Leonardo’s surviving design materials were used as the basis for sculptures intended to bring the project to life.

Leonardo’s Horse, replica in Milan

Other Drawings

In this section there is a wide range of Leonardo’s detailed drawings, demonstrating the diverse subjects he studied, as well as showcasing his consummate skill in depicting all aspects of human life and the natural world.

Study of Arms and Hands, c. 1474

Man with a Staff, c. 1476-1480

Siege Machine, c. 1480

Saint Sebastion, c. 1480

Study of Horse and Rider, c. 1480

Study of Horse and Rider, c. 1481

Designs for a Boat, c. 1485-7

An Artillery Park, c. 1487

Study of a Young Woman in Profile, c. 1485-7

Grotesque Profile, c. 1487-90

Design for a Flying Machine, c. 1488

Design for a Flying Machine, c. 1488

Proportions of the Head, c. 1488-9

Study for the Sforza Monument, c. 1488-9

View of a Skull, c. 1489

View of a Skull, c. 1489

View of a Skull, c. 1489

Study of a Womb, c. 1489

Proportions of the Face and Eye, c. 1489

Five Characters in a Comic Scene, c. 1490

Ill-matched Couple, c. 1490

Study of a Woman, c. 1490

Christ Figure, c. 1490-5

Studies of Concave Mirrors of Differing Curvatures, c. 1492

Coition of a Hemisected Man and Woman, c. 1492

Study for the Last Supper, c. 1495

Stretching Device for a Barrel Spring, c. 1498

Anatomy of a Male Nude, c 1504-6

A Grotesque Head, c. 1504-7

Design for a Flying Machine, c. 1505

Study for the Head of Leda, c. 1505-7

Study for the Kneeling Leda, c. 1505-7

The Principal Organs and Vascular and Urino-Genital Systems of a Woman, c. 1507

Study for the Trivulzio Monument, c. 1508

Study of Brain Physiology, c. 1508

Studies of Water passing Obstacles and falling, c. 1508-9

Studies of the Shoulder and Neck, c. 1509-1510

Studies of the Shoulder and Neck, c. 1509-1510

Studies of the Shoulder and Neck, c. 1509-1510

Sedge, c. 1510

Studies of the Arm showing the Movements made by the Biceps, c. 1510

Views of a Fetus in the Womb, c. 1510-12

Head of Saint Anne, c. 1510-5

Study of Cats and Other Animals c. 1513

Old Man with Water Studies, c. 1513

Anatomy of the Neck, c. 1515

Detail from a Study of a Dragon Costume, c. 1517-8

Masquerader in the guise of a Prisoner, c. 1517-8

Study of Skeletons

Study of a Figure for the Battle of Anghiari

Study of a foetus in the womb, c. 1510

Anatomical study of the arm, (c. 1510)

Leonardo da Vinci’s very accurate map of Imola, created for Cesare Borgia

The Notebooks

‘Francis I of France receiving the last breath of Leonardo da Vinci’, by the French Master Ingres, 1818

The Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci

Translated by Jean Paul Richter

Leonardo’s notes and drawings demonstrate an enormous range of interests and preoccupations, some as mundane as lists of groceries and people who owed him money and some as intriguing as designs for wings and shoes for walking on water. There are compositions for paintings, studies of details and drapery, studies of faces and emotions, of animals, babies, dissections, plant studies, rock formations, whirlpools, war machines, helicopters and architecture.

These notebooks, which were originally loose papers of different types and sizes, distributed by friends after his death, have found their way into major collections such as the Royal Library at Windsor Castle, the Louvre, the Biblioteca Nacional de España, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan which holds the twelve-volume Codex Atlanticus, and British Library in London.

The Codex Leicester, named after Thomas Coke, later created Earl of Leicester, who purchased it in 1719, is one of the most famous notebooks. The manuscript holds the record for the current sale price of any book, when it was sold to Bill Gates at Christie’s auction house on 11 November 1994 in New York for $30,802,500. The Codex provides an invaluable insight into the inquisitive mind of the artist and scientist, serving as an exceptional illustration of the link between art and science and the imagination of the scientific process.

Leonardo’s notes appear to have been intended for publication because many of the sheets have a form and order that would facilitate this. In many cases a single topic, for example, the heart or the human fetus, is covered in detail in both words and pictures on a single sheet. Exactly why they were never published in Leonardo’s lifetime is unknown.

Jean Paul (1763-1825) — a German Romantic writer, best known for his humorous novels and stories, as well as his translation of Leonardo’s notebooks

A page of the Codex Leicester

THE NOTEBOOKS

CONTENTS

THE PLATES

VOLUME I

PREFACE.

I. PROLEGOMENA AND GENERAL INTRODUCTION TO THE BOOK ON PAINTING

II. LINEAR PERSPECTIVE.

III. SIX BOOKS ON LIGHT AND SHADE.

IV. PERSPECTIVE OF DISAPPEARANCE.

V. THEORY OF COLOURS.

VI. PERSPECTIVE OF COLOUR AND AERIAL PERSPECTIVE.

VII. ON THE PROPORTIONS AND ON THE MOVEMENTS OF THE HUMAN FIGURE.

VIII. BOTANY FOR PAINTERS AND ELEMENTS OF LANDSCAPE PAINTING.

IX. THE PRACTICE OF PAINTING.

X. STUDIES AND SKETCHES FOR PICTURES AND DECORATIONS.

VOLUME II

XI. THE NOTES ON SCULPTURE.

XII. ARCHITECTURAL DESIGNS.

XIII. THEORETICAL WRITINGS ON ARCHITECTURE.

XIV. ANATOMY, ZOOLOGY AND PHYSIOLOGY.

XV. ASTRONOMY.

XVI. PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY.

XVII. TOPOGRAPHICAL NOTES.

XVIII. NAVAL WARFARE. — MECHANICAL APPLIANCES. — MUSIC.

XIX. PHILOSOPHICAL MAXIMS. MORALS. POLEMICS AND SPECULATIONS.

XX. HUMOROUS WRITINGS.

XXI. LETTERS. PERSONAL RECORDS. DATED NOTES.

XXII. MISCELLANEOUS NOTES.

Windsor Castle, England — home to many of Leonardo’s notebook works

THE PLATES

In this table, readers can access the original plates from Jean Paul Richter’s translation of the notebooks. You may wish to bookmark this page for future reference.

PLATE I

PLATE II

PLATE III

PLATE IV

PLATE V

PLATE VI

PLATE VII

PLATE VIII

PLATE IX

PLATE X

PLATE XI

PLATE XII

PLATE XIII

PLATE XIV

PLATE XV

PLATE XVI

PLATE XVII

PLATE XVIII

PLATE XIX

PLATE XX

PLATE XXI

PLATE XXII

PLATE XXIII

PLATE XXIV

PLATE XXV

PLATE XXVI

PLATE XXVII

PLATE XXVIII

PLATE XXIX

PLATE XXX

PLATE XXXI

PLATE XXXII

PLATE XXXIII

PLATE XXXIV

PLATE XXXV

PLATE XXXVI

PLATE XXXVII

PLATE XXXVIII

PLATE XXXIX

PLATE XL

PLATE XLI

PLATE XLII

PLATE XLIII

PLATE XLIV

PLATE XLV

PLATE XLVI

PLATE XLVII

PLATE XLVIII

PLATE XLIX

PLATE L

PLATE LI

PLATE LII

PLATE LIII

PLATE LIV

PLATE LV

PLATE LVI

PLATE LVII

PLATE LVIII

PLATE LIX

PLATE LX

PLATE LXI

PLATE LXII

PLATE LXIII

PLATE LXIV

PLATE LXV

PLATE LXVI

PLATE LXVII

PLATE LXVIII

PLATE LXIX

PLATE LXX

PLATE LXXI

PLATE LXXII

PLATE LXXIII

PLATE LXXIV

PLATE LXXV

PLATE LXXVI

PLATE LXXVII

PLATE LXXVIII

PLATE LXXIX

PLATE LXXX

PLATE LXXXI

PLATE LXXXII

PLATE LXXXIII

PLATE LXXXIV

PLATE LXXXV

PLATE LXXXVI

PLATE LXXXVII

PLATE LXXXVIII

PLATE LXXXIX

PLATE XC