Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Arachne Press

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

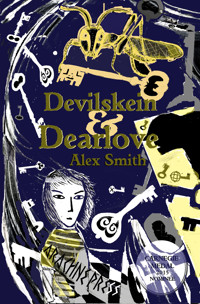

Just as Neil Gaiman's The Graveyard Book reworked Kipling's The Jungle Book for a modern audience with a liking for the supernatural, Devilskein & Dearlove is a darker, more edgy, contemporary reworking of Frances Hodgson Burnett's classic The Secret Garden. An orphaned teenager is taken in by a reluctant distant relative, and in her new home makes an unexpected friend and finds a secret realm. It has shades of the quirky fantastical in the style of Miyazaki's (Studio Ghibli) animated films like Spirited Away and Howl's Moving Castle (originally a novel by Diana Wynne Jones). Alex says "As a child The Secret Garden was one of my first favourite novels - one of the first I relished reading by myself. Although Devilskein & Dearlove is very different, it was inspired by that novel and its themes." "Alex Smith's quirky imagination knows no bounds." - André Brink

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 373

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

DEVILSKEIN

&

DEARLOVE Alex Smith

CONTENTS

1Grumpy Girl2Across Time3Aunt Kate4A Demon Howls in the Stairwell5Surely You Heard That Demonic Howl?6The Bunch of Keys7The Cricket Leads the Way8The Garden of the Humble Politician9The Cricket and the Boy10The Cabinet of Albertus Devilskein11Gardens and Ocean Cabinets12I Am Julius Monk13A Young Demon14High School and Key Work15Stubborn Ms Dearlove16The Wrath of Julius Monk17End of Days18Dangerous Times19Long Street Night Life20Mr Devilskein21AftermathAbout the AuthorMore from Arachne PressFor my baby boy and his wonderful dad

1 Grumpy Girl

When Erin Dearlove arrived at Van Riebeek Heights to live with her reluctant Aunt Kate, the neighbours all said she was an obnoxious brat, too thin, spoiled, wild-looking, and with a habit of speaking like she’d swallowed a dictionary. They were pretty spot on. Her face was scrawny, her sandy amber hair unbrushed, she used convoluted vocabulary with spite, and she never smiled because she had no parents. Apart from Aunt Kate, who had been sworn to secrecy, nobody quite knew what had happened to them. Erin relished shocking people by telling them her mother and father had been eaten by a crocodile. ‘Can’t undo it, can’t forget it,’ she’d say, then add, ‘I found bits of them on the shaggy white carpet of our designer home.’

Some people’s jaws dropped open in horror. Erin liked that.

But the truth of her parents’ demise was even uglier than a crocodile.

In the first few days at Van Riebeek Heights she found it impossible to avoid being cornered by overwhelmingly chatty grown-ups endowed with a blur of names like Nozizwe, Ebindenyefa, Zibima Oruh, Granny Wokoya, Aunty Talmakies, Varsha Lalla, Tekenatei, Ayodele, Boitumelo and Jaroslav Chudej, and when their unwelcome geniality forced her into conversation, Erin would boast how her dad had been an important and very corrupt banker. ‘Mr Dearlove, my father, was a splenetic, abusive man,’ she’d say. ‘He had many enemies, but even he did not deserve the horrendous fate that befell him and his wife and their irksome dog.’ After telling the story a few times, she’d added that yapping terrier, but she never once mentioned the brother she had lost on that same unspeakable morning.

Her bad reputation at Van Riebeek Heights was sealed one Tuesday in the hour before twilight. ‘Of course,’ she said to Mrs Puoane, a flabbergasted neighbour from upstairs, who was seven months pregnant with twins, ‘I was fascinated by their fabulous parties, their beautiful clothes, and famous friends who often appeared in glossy magazines and international newspapers, but the Dearloves were hard to get close to.’ About this, Erin just shrugged. ‘There was no warmth in that architecturally astonishing house. It’s almost a relief that those Dearloves are gone.’ But as she said the words, her heart constricted; it ached and so she added with venom, ‘Parents are so overrated. With the way science is advancing, they’ll soon be superfluous.’

Ping!Ping!Ping! went the Company Soulometer and Devilskein regarded the scurrilous contraption on his kitchen table with satisfaction. The Tuesday sun had sunk and night was on its way and the device alerted him to a quarry on another continent. The contraption was something like a GPS, except it dated back almost four thousand years, back to the early days of Babylon, and instead of directing a Companyman to a place, it gave the longitude and latitude of any living person who had, with true intent, thought or uttered aloud some variation of: ‘Oh, I would sell my soul for/to…’. Of course, the Company did not buy souls, nobody can buy a soul: it is priceless; it has to be pledged. In order to procure these most precious of commodities, the Company dangled all manner of carrots and smidgens of hope in the way of desperate would-be traders: ‘Your soul is not sold, it is pawned, and it is security for your debt to the Company; it is redeemable on certain terms. So if you or somebody you know can muster the wherewithal within a reasonable amount of time, there is a chance you can have it back. Until such time, it will reside in a locked room in our Indeterminate Vault. And like gold bullion for a government, its great treasury of souls made the Company a universal superpower. Exactly the nature of the said ‘wherewithal’, the specifics of the certain terms and the length of the reasonable time were all things never made obvious. Company policy was never obvious. Its magic was too shadowy and despicable for any such contractual transparency. However, betwixt the hot air and subterfuge, trading in souls did in fact have very definite rules. And every room in the vault of endlessly nested doors had a key.

Erin smiled cruelly at Mrs Puoane, her pregnant neighbour. ‘I do not miss Mother and I do not miss Father, but nor do I relish the ridiculously small size of my Aunt Kate’s apartment on this filthy Long Street.’ She sighed. ‘I suppose I have to face the fact that I am well and truly poor.’

As night absorbed any remnants of that Tuesday, Erin went on to plunder her imagination and further regale Mrs Puoane with how having always been rich and given everything she ever wanted, she assumed that living with Aunt Kate was a temporary measure until the complications with the bank were sorted out and she would have her four-poster double bed and the private forest, vineyards, peacocks and rolling lawns of the estate back again.

Two doors down, a boy who had already heard most of the blah about the mansion with the glass stairs was surprised when he happened to open one of his mother’s old copies of Garden & Home to see an article about a convicted fraudster, a banker who boasted that he was out of prison before he even went in, and who happened to live in a mansion with glass stairs. His place was so big it required a staff of five gardeners and five housekeepers. But his surname was not Dearlove. ‘And look!’ muttered Kelwyn Talmakies to himself. ‘There’s a peacock in the vineyard.’ On reading the article Kelwyn learned too that the tycoon who owned it despised anything cheap, bohemian, homemade or crafty; he wore only Armani clothes, Italian bespoke shoes and Rolex watches. Kelwyn frowned, but his thoughts were interrupted.

‘Rover 1, come in, Rover 1, come in,’ crackled a voice from a walkie-talkie lying beside Kelwyn.

He rolled over and picked it up. ‘Rover 1, here. What’s up, Rover 2?’

‘We have a situation,’ said the fuzzy voice named Rover 2. ‘Need back-up on the corner of Church Street.’

‘Be right there. Over and out.’

Duty, in the form of his sidekick, Sipho, aka Rover 2, who lived on the first floor with his grandmother, had radioed in and Kelwyn, unsure what to make of the article, stashed the magazine under his bed. In doing so he was chuffed to discover one of his favourite penknives: an Opinel with a carbon steel blade and a comfortable hand-carved wooden handle; he’d saved up to buy it from ‘Serendipity’ a musty, resin-scented antiques and oddments shop in Long Street. He collected penknives and had a particular soft spot for Opinels – ‘the peasant’s knife’, his father had told him, before vanishing back to France – and Kelwyn owned three of them.

*

Rubbing his hands in anticipation of a deal, Devilskein, a Companyman with a formidable reputation, noted the co-ordinates of a middle-aged actor in an apartment in Istanbul. The fellow in peril fancied he was a theatrical genius waiting to be discovered. ‘Honestly, I would sell my soul for a good part,’ the actor said to a confidante as they sat smoking on a roof-top terrace with a view of the Bosphorus.

The first law of soul trading is that of ‘Ask and You Shall Receive’, like easy credit (but in the small print on any contract with the Company, the crippling interest rate on borrowings runs into several thousand percent).

Erin flickered her eyelashes and made a final bid to push all those terribly friendly people at Van Riebeek Heights away for good: ‘It’s no wonder I ignore the children around here,’ she said to Mrs Puoane, whose ankles were starting to swell from having to stand for so long. ‘They’re rather dirty, low-class and uncouth. And besides, most of them are boys and I have nothing in common with them or anybody else on this noisy street where my aunt lives.’

Mrs Puoane rubbed her belly and groaned: one of the twins’ small feet was kicking eagerly and its sibling was thumping its mother-to-be right under her ribs.

And so it was that after only a week at Van Riebeek Heights, her petulance earned Erin a nickname: ‘Grumpy Girl’. It was Kelwyn Talmakies, owner of the walkie-talkie and the exceptional penknife, eldest son of Leilene Talmakies (who was Aunt Kate’s friend and favourite neighbour) who started calling Erin that name first. He was a stocky teen with caramel skin, blond hair and a fighting spirit. His nails were usually full of mud, and his T-shirt often streaked with earth – despite Leilene Talmakies’ best efforts to encourage her son to bathe twice daily, he frequently smelled of pungent kelp. He always kept a penknife in his pocket. To his mother’s chagrin, Kelwyn had a tattoo of a gecko on his right calf, for shortly before abandoning his family, his zoologist father had instigated the inking of this reptile on his son’s leg. What’s more, Kelwyn seemed to relish goading Erin with his friendliness. But his greatest crime was being the same age as her dear, dear brother who was no more. For that alone she detested Kelwyn from the moment she laid eyes on him.

‘You stink,’ she’d said to his initial ‘How do you do?’

‘It’s called “Seagrow”,’ Kelwyn said, sniffing his shirt happily. ‘It’s liquid fertiliser for plants.’ Then he ventured, ‘Do you read Garden & Home?’

Her face crumpled with disdain. ‘Don’t be absurd.’

She had, until he interrupted her, been reading a book, just as she’d done every afternoon of her life when it was still normal. The only difference was, instead of being propped up on a cosy sofa, surrounded by a great pile of checked and striped and floral cushions made and lovingly down-filled by her Mama, she was sitting on a flight of gritty concrete stairs in the dismal stairwell of Van Riebeek Heights; her mother was gone forever and eternally hurt in a way that no person should be hurt. Erin could pretend all manner of things (she was very good at that, indeed), but no matter how desperately her heart wished it, she could not erase the truth, nor undo what had been done.

A heatwave had hit the town, that January was fast becoming the hottest in recorded history. At least it was cooler there on those concrete stairs. And it should have been suitably lonely, for it was one of the higher floors; Erin aimed to escape detection and the attentions of the children in the lower floors, but alas, Kelwyn, who smelled of seaweed and asked silly questions about magazines, had found her out.

Kelwyn wiped sweat from his brow, leaving a smear of potting soil on his forehead.

‘So this is where you hide,’ he said, deciding to let the Garden & Home thing go. He tilted his head, trying to see the cover of her book.

‘Go away.’ Erin turned her back and dipped the book to obscure the cover in the hope that he couldn’t see the title.

But he’d recognised it immediately, as a zillion other people would have done too. ‘Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban,’ he said, triumphant. ‘I loved that series. Hey, I’ve got them all, so if you’d like to borrow number four…’

‘Why would I want your books?’ she said, scathingly, as if he and his books were diseased. ‘They probably stink as much as you do.’

But as much as she was angry, Kelwyn was equally jovial: they were perfect opposites. ‘Well,’ he said, unfazed. ‘Books are expensive and maybe you don’t belong to a library around here, being new and all.’ He noticed a small brooch pinned to her shirt. ‘I like your owl.’

Mention of the precious owl unsettled her and that made her loathe Kelwyn all the more. He had no right to like the brooch.

Along its four kilometres, Long Street below jangled with cars and coins (paid to parking marshals, tips left for waiters, currency exchanged for curios), and women in high heels who smelled of sun cream and coffee as they passed by brightly repainted and restored French, Cape Dutch, Victorian, and Art Deco buildings.

Higher up in the sixties block known as Van Riebeek Heights, which at six storeys towered over the street’s mostly historic architecture, Devilskein was making notes in the Company ledger. And like any master of deception he made sure to include some error. The Company’s contracts, and their deals, were laced with falsehood and equivocation. The truth of the matter was that once pawned, a soul was almost certainly lost because the Company books were fiddled and riddled with cunning sub-clauses and impossible to fathom appendices; who knew what keys opened which doors? On the kitchen table beside Devilskein was a heap of rather exquisite keys. And the walls of the kitchen were lined with shoeboxes, each one filled to the brim with a clatter of ‘lost’ keys.

The second law of soul trading was that of ‘Compound Interest’, an ugly cunning triumph of usurers across time. But there was some honour to the business – the Company never took souls that were contractually signed away with any unwillingness by their owners. And of course, the Company, never spoke of ‘taking’ a soul; souls were pledged to them. They were merely brokers, and happened to make use of the souls in their indeterminate possession like a bank might use its clients’ funds to speculate in other markets. And keys were never thrown away, why that would be unjust; the keys were always somewhere, in some box or other, but with so many keys the chance of finding any particular one was slimmer than a cat’s whisker.

Erin narrowed her eyes. ‘Before the crocodile bit him in half, my father was a millionaire. So I certainly don’t need your charity or your stinky old books. Leave me alone, stupid.’

Kelwyn was a bit hurt by her rejection – briefly he contemplated a mean retort relating to that article in House & Garden – but he brushed that impulse aside; it was not in his nature to be petty, he was a generous, warm, good-humoured soul. But fifteen-year-old Kelwyn, the saviour of all manner of damaged frogs, snakes, insects and plants, did have a naughty streak. ‘Lighten up,’ he said with a laugh, and poked her and started to tickle and tease her in a bid to lift her from her gloom. He started to sing: ‘Erin is a grumpy girl! Erin is a grumpy girl. Grumpy, grumpy, grumpy, grumpy, grumpy—’

‘Stop it!’ she swatted him. ‘Go away, get away!’

A fat and crispy cockroach slipped out of a drainpipe and scuttled along the ridge of Erin’s step.

She didn’t make any kind of girlish squeal, which impressed Kelwyn, and he smiled, which she took the wrong way.

‘Go away, I said!’

Kelwyn didn’t go, and nor did the roach, so Erin got up and started away down the stairs, first walking and then running, with Kelwyn following, singing the ‘Grumpy Girl’ song and tugging at her ponytail, which made her all the more infuriated. On the way down, they were spotted by several other children – Duduzile, Celine, Ishara, Tutu, Sipho (aka Rover 2), Olanma, Max, Lauri, Dajana and Malika – whose ages ranged from four to thirteen and who thought it a great sport to join in the singing.

They followed her to Aunt Kate’s front door, which was locked, and Erin had forgotten her key. She banged on it loudly and called to be let in.

Steam billowed inside the apartment; music blared; Aunt Kate frothed soap and put a razor to her leg.

It had become too much for Erin. Kelwyn realised she was close to tears and so he called the choir of bullying children to a hush.

‘Come on, Erin,’ effortlessly affectionate, unusually so for a boy of his age, he put an arm around Erin’s shoulder. ‘We’re just playing – let’s all be friends.’

Pricklier than an angry porcupine, she pushed him away. ‘Never. Not in a thousand years. I don’t need friends.’

‘If you keep on being grumpy,’ said Kelwyn, ‘you’re only going to make yourself miserable and the only friend you’ll have here is Mr Devilskein,’ he made a whooo-whoo ghost-type sound, ‘the creature who lives on the top floor.’

The younger children thought that a great joke and fell about laughing.

Mirth jingled and mingled with the stairwell heat. On the top floor a kettle boiled and a poodle yawned. Mr Devilskein dipped a quill pen into a pot of Sabbath black ink made from the bones of burned witches. The label said: A.P. Jones Hellstain. Fine Unholy Ink for Turncoats, Tax Collectors, Lawyers, Snake-oil Salesmen and other Malefactors. It amused Devilskein, who had purchased it once on a trip to Salem, the town infamous for its 1692 witchcraft trials. Whenever he used the ink, it made him smile.

‘Well, quite frankly, I’d rather be Mr Devilskein’s friend than yours.’ Erin was incensed, so added haughtily, ‘In fact, I’m due to have tea with him this evening.’

Something about that impressed the children around her. Eleven-year-old Duduzile whistled.

‘Tea with the monster,’ whispered six-year-old Ishara, agog.

‘I don’t believe you,’ said Kelwyn. ‘You’re fibbing, Erin Dearlove.’

‘What you believe, boy, is of absolutely no interest to me,’ said Erin, with all the scorn her thirteen-year-old self could muster.

‘I’ll know if you’re lying. I’ll follow you to see.’

‘Do whatever you like. Mr Devilskein and I are having tea and scones at six p.m. tonight.’

‘That’s a strange time for tea and scones,’ said Kelwyn.

In the heavens above, a cloud moved. A shaft of blinding sun burned at the creases in Erin’s brow.

‘You know nothing about time,’ she said, trying to be superior and enigmatic.

‘What do you know about him?’ Kelwyn asked. ‘Nothing, I bet.’

‘It’s none of your damn business!’

Kelwyn also knew nothing other than the second-hand embroideries of rumour. ‘Have you even seen him? His scars? His nails? He is a monster and he’s grumpy just like you. He’ll probably eat you for tea after you’ve eaten your scones.’

‘Rubbish.’

Fortunately, Aunt Kate opened the door just then. Water glistened on her shoulders; her legs were streaked with cocoa butter moisturiser.

‘I’m so sorry, love,’ said Aunt Kate, still wrapped in a towel, ‘I was–’

‘At last!’ Erin turned her back on Kelwyn and pushed past Aunt Kate.

‘–in the shower,’ said Aunt Kate, finishing her sentence.

Apart from Kelwyn, the children scattered, as they did not want to get a scolding for being bullies.

‘Enjoy your tea, Grumpy Girl,’ called Kelwyn after Erin. ‘It may be your last. I’ll be waiting to see if you’re a liar as well as a grouch.’

Erin’s bedroom door slammed shut; Kelwyn winked at Aunt Kate and gave her an angelic grin.

She ruffled his hair and said, ‘You’re naughty, Kelwyn, for teasing her like that. She’s had…’ Aunt Kate’s tone became serious and sad, ‘…the worst experience imaginable.’

‘What, in the mansion with glass stairs?’ said Kelwyn.

In a whisper, Aunt Kate, who could no longer bear the burden of knowing what she knew, said, ‘Promise you will never ever tell anyone at Van Riebeek Heights what I am about to tell you?’

‘Why?’ Kelwyn asked.

‘Because Erin wants it like that, but – well, it’s hurting her. I think at least one of you should know. But only you.’

‘Then I promise,’ he said earnestly.

Aunt Kate’s whisper was almost inaudible. ‘Her family did not live in a mansion with glass stairs, they were farmers.’

‘Rover 1, come in please,’ the old walkie-talkie in Kelwyn’s back pocket hissed.

Kelwyn grabbed it and said into it, ‘Not now, Rover 2. Am busy.’ He shoved it back into his pocket. ‘Sorry about that, Aunt Kate. Please go on.’

She smiled, a bit sadly. ‘They did have a rambling farmhouse and hundreds of hectares of grazing for cattle.’ She paused, as if recalling the place in her mind’s eye, ‘But they weren’t rich, the house was run-down. Their only wealth was that land and those animals.’ She frowned. ‘Then the cattle were poisoned, thousands of them. And as for the land, no buyer will touch it after what happened to the Dearloves… so Erin, the only survivor, is penniless.’

Ping!Ping!Ping! went the Company Soulometer. Devilskein paused from his work with the ledger and placed the quill back into its pot of awful ink. A new set of co-ordinates gleamed on the machine’s grid. This one was connected to a past date – the brokering of souls did not conform to usual laws of linear time and fixed place; it was an inter-dimensional business. So it could be that a Babylonian concern was able to produce a contraption that made use of round-earth geographical norms established dozens of centuries after Babylon vanished. Devilskein raised his brow: the quarry was a master artist of the High Renaissance. He was a genius sculptor, whose overwhelming ambition was matched only by the pungent stench of his body that was never washed; he was poor as can be, never changed his clothes, but what talent that soul possessed! And yet the artist was suffering from a debilitating spell of gloom in the form of artistic block: His prodigious imagination had gone blank and he wanted it back at any price. Devilskein’s delight was perhaps too much for his ancient heart, which constricted so painfully he thought he might faint. When the moment passed, he rubbed his chest and said to his French poodle (who was asleep), ‘The arteries of my wretched heart are clogged something awful. I suspect it’s going to pack up soon.’ He sighed and lamented again, ‘I suppose we should stop eating the fat on our lamb chops and having clotted cream with our pudding.’ He heaved a sigh of great disgruntlement. ‘We should give up whisky, cigars and foie gras. Pah! Never! But I suppose some day soon I will have to visit my Physician.’

Even though Erin had said she didn’t care what Kelwyn thought about her, she actually did; Erin cared about a lot of things she tried not to, and she hated herself for that. In her room, with the door locked, she tried to read more of her Harry Potter book, but she couldn’t stop thinking about the so-called monster, Mr Devilskein. When it was just before six, she when into her aunt’s kitchenette and reached up high to the back of the cupboard for the new packet of biscuits: Lemon Creams. A jar of honey fell over, rolled sideways, and crashed onto the counter, but didn’t crack.

Her father had liked honey.

Her father? Not the mean one who got eaten by a crocodile, but the real one, who wasn’t rich, but who was her dad. Erin stared at the jar and thought she must be in a dream – this can’t be real life, it’s not meant to be like this, is it? Her limbs felt heavy with a deeply horrible realisation. She touched the silver owl brooch she always liked to have pinned on her shirt – it had been her mother’s brooch. Then suddenly as it had come, the moment passed, and once again she was just a grumpy girl who’d been orphaned by a crocodile.

She unlatched the front door and, biscuits in hand, she marched up the stairs to the top floor.

Kelwyn was waiting for her. He looked at the biscuits.

‘I thought you were having scones?’ he joked, awkwardly. He wanted to say something else, something better, more comforting, but what could he say? There weren’t any right words for things like what happened to her family, those things just shouldn’t happen. Besides, what could he say without letting on that Erin’s aunt had told him what she, and now, he, had sworn not to tell.

‘I changed my mind. Anyway, I prefer biscuits.’ Erin stuck her nose in the air and passed him.

‘It’s the last door at the end,’ he said, still at loss for the right words. ‘In case you didn’t know.’ He could have kicked himself.

But she was oblivious and undeterred. ‘I knew that.’

Nobody Kelwyn knew of in the block had ever been brave enough to venture into the creepy flat because the monster that lurked there was said (variously) to be evil incarnate, a face-eater, an eyeball collector, a tokoloshe, a fleshless ghoul, a Satan worshipper, a creature with blades for fingers. None of it could be true though – Kelwyn thought the monster was probably just a vivid conglomeration of nightmares, books and horror films and maybe in part the invention of parents in the block who didn’t want their children playing around in a dirty, abandoned flat. Still, the Devilskein myth was too fearsome for anyone to tempt fate by actually going into the infamous apartment 6616 – after all, everyone knows that where there is smoke there could well be just a little fire.

Kelwyn sighed, and gave up trying to dissuade her, thinking Erin would find out soon enough. ‘Well, I’ll be waiting out here,’ he said, then he thought of something better to say: ‘If you need me, scream, and I’ll come and save you.’

She gave him a withering look and said, ‘This isn’t a trashy romance novel. I don’t need to be saved, thank you very much.’

With that, she knocked on the door of the apartment. Her hand holding the Lemon Creams was trembling.

Not far away, a luxury cruise ship blew its horn, signalling its departure from the safety of the harbour at the end of Lower Long Street.

Even if there was no monster, Kelwyn admired Erin’s courage. And he liked her fair amber hair that made wisps and waves around her pale face.

‘I know you were making it up about the tea and scones,’ he said, quite gently, thinking not about tea with Devilskein, but about the other things, including the House & Garden article.

‘You know nothing,’ she said with venom. ‘Now, for the last time, GO AWAY! You’re like a stray dog. I’ve got no scraps for you, dumb dog, so scram!’ She gave him another scowl before knocking again more loudly. Irritation made her confident; she was very curious to see this infamous man named Devilskein. Was he really a monster? No, probably just a recluse, maybe he was disfigured, burned in a fire. Whatever he looked like, she doubted anything could out-monster her hidden-away grief. Since she disliked everybody else in Van Riebeek Heights, perhaps he could be her friend, or better still, she thought, if he really was a proper monster (not just a hideous recluse), perhaps he could swallow her and her stupid sad heart up. I’m all yours, monster.

She knocked again and called, ‘Hello!’

‘You may not have been making it up, but I was,’ Kelwyn said, he turned and sauntered away, kind of hoping she would follow. ‘This floor is deserted. The monster is just a story the kids around here scare each other with.’

Erin ignored him and knocked a third time.

A meat supply truck rumbled down Long Street; it had a delivery of lamb, beef and crocodile carcasses for a restaurant called Mama Africa.

The wind gusted and in a sweep, the door to Devilskein’s apartment opened with a creak.

Kelwyn stopped and turned, thinking the lock on that derelict flat must have been faulty, causing the door to fall open. But he was too far off to see anything.

What Erin saw made her want to run, but she would not allow Kelwyn such satisfaction. She thrust the packet of biscuits forward towards the horrifying being in front of her. ‘I’ve brought biscuits for our tea, instead of scones,’ she said loudly, so that Kelwyn could hear.

‘What on earth are you?’ said Devilskein, taking in the skinny girl with scraggly hair and a green T-shirt the same colour as her big, terrified eyes. ‘What manner of ugly human thing?’

‘I could ask the same of you,’ Erin said in a scathing whisper. ‘Now are you going to let me in or not?’

He narrowed his lashless lids and cocked his hairless head; he could see into her soul and was intrigued at how it shimmered, but still, Devilskein was unprepared for a social event like tea and biscuits. ‘Really, you wish to come in? Are you sure, little girl?’ An antique gadget on his belt, like a compass crossed with a calculator, pulsed with an ominous red light.

In the near distance, the cruise liner edged out into Table Bay, followed by seals, which were being watched by sharks.

Erin peered into the gloom beyond him – from ceiling to floor the walls were lined with shoeboxes. ‘But of course, I’m sure,’ she said, snippily. ‘Otherwise I wouldn’t be here, would I?’

Again her soul caught his attention.

She has a living soulmate! Devilskein thought, calculating possibilities. Soulmates were in fact rather rare. And, unless he was mistaken, when joined and transplanted, then, ahhh! The twinned hearts of soulmates made a sum of immortality, or at least another thousand good years for a Companyman like Devilskein. What uncommon luck! I must speak to the Physician immediately. He growled softly, but she pretended not to hear. In a strong voice, especially for Kelwyn’s benefit, Erin added, ‘Our arrangement was for tea at six. Have you forgotten?’

Excited, but still perplexed, Devilskein suggested his place was untidy. ‘Far too untidy for a visitor.’

‘Never mind that. You can tidy up and I will put on the kettle.’ Taking a deep breath, Erin summoned all her courage and pushed past Mr Devilskein. For the first time in one thousand three hundred years, Devilskein was shocked. He closed the door behind Erin and for the briefest moment the light bulbs faltered and darkness engulfed them.

Kelwyn’s jaw dropped.

‘What is this place?’ asked Erin, looking about at the shadowy gloom with a vaulted ceiling. ‘It’s like something out of an antique book.’ A pair of eyes beneath a flop of brown curls watched her from the kitchen door. The creature’s brown nose twitched.

‘The kettle is this way,’ said Devilskein, indicating a door. ‘You will boil it, as you said you would, and we will have tea as you said we would. You will not expect me to talk to you, and you will not go into any rooms other than the kitchen. And when you are in the kitchen, you will not poke about in any of the boxes or cupboards.’

‘Why would I want to poke about?’ Erin said. ‘I am not domestically inclined. What could your kitchen possibly contain that is more interesting than any other kitchen on the planet?’ And with that she went off to find the kettle.

On entering the kitchen, she frowned at the towers of shoeboxes, but didn’t dare comment on them.

There was a gaping maw where a stove should have been (Devilskein enjoyed eating but not cooking; he was not a creator) and in its place there was a large French poodle nestled in a basket.

‘Dammit,’ said Devilskein, remembering an important piece of equipment left out on the kitchen table. It would not do for the scrawny girl to see the Company Soulometer. And besides he wished to make contact with his Physician. He tapped the gadget on his belt and the pulsing red light turned purple; it gave out a soft sigh of pernicious gas.

Erin filled the kettle with water and turned it on, and only then became aware of mist (not kettle steam), a peculiar sweet-scented greyness that grew thicker and made her eyelids heavy. She noticed the fat digits of a clock offering six minutes past six and yawned.

Devilskein caught her as she fell asleep.

2 Across Time

It seemed to Erin that she had been sleeping for an age, but when she opened her eyes, the kitchen clock was still showing the same time. Water from a leaky tap dripped into the metal sink; a dragonfly hovered near the moisture. Devilskein had made a pot of tea and set out the biscuits on a turquoise platter. The teapot, a nicely fulsome round one, was turquoise too. There were no windows, but she could hear cicadas singing thickly in some distant garden. Remembering her fearsome host’s instruction not to make conversation, Erin took a biscuit and ate it quickly and in silence. In fact, she was ravenous, so she ate five in succession and washed them down with the tea, which was excellent, neither too milky nor too strong.

Devilskein watched over the steam of his cup, tapping a long fingernail on the delicate porcelain. His Physician had confirmed the unique value of the hearts of soulmates, one heart was good, but to have them both, now that was a prize. There was a catch, however, they needed to have found each other in order for their uniquely powerful bond to imbue their hearts with immortality. It would require some plotting, he mused, in the wispy steam of tea.

Erin tried not to stare at the tiny foreign words carved on Devilskein’s scarred face, nor to look at the place where his ear should have been.

All of a sudden, the gadget on his belt emitted an unnerving wail.

Yeeowl-whaawheeeee-whaaaaaaa-yeeeowl!

The kitchen shuddered like a locomotive leaving a station.

‘Are we moving?’

Devilskein frowned. How absolutely inconvenient. He clutched the device, deactivated the irksome siren and, with a tap of his finger, made it issue forth a second dose of that pernicious gas.

Erin supposed it was sleepiness that made it seem as if she was in a train carriage. She yawned again and, feeling oddly content and cheerful, rested her head on her arms. Her legs dangled; her shoes were no longer on her feet. The clock ticked with metallic, somnambulant precision: one weighty tock followed by a lighter tick.

The contraption on Devilskein’s belt had indeed moved the kitchen in time and space.

In walked an irate man in a robe embroidered with palm trees. He glanced at the sleeping girl. ‘I’m here for my key.’

Devilskein tapped the hole where his right ear should have been and pretended he couldn’t hear.

The robed man repeated his request.

As a Companyman, there was nothing more important to Devilskein than maintaining control of his hoard of keys. It was immeasurably displeasing to be faced with the possibility of having to give a person back their soul.

‘My key,’ said the robed man. ‘I have fulfilled my side of the bargain and I DEMAND MY KEY!’

Devilskein grunted and pulled a wooden stepladder out from under the table. He used the ladder to access the most precariously positioned shoebox at the top of the tallest of the towers. He climbed down, opened the box, and placed it in front of the robed man. The box was full of keys, hundreds of keys.

‘It might be in there,’ said Devilskein. He rummaged in the box. ‘No, not in this one.’

The man scowled. ‘You haven’t looked very hard.’

Devilskein narrowed his lashless eyes. ‘I tell you it is not there, but there are six thousand thousand other boxes in this place.’ He checked his watch. ‘Unfortunately, I have other things to do right now, and according to your contract you are obliged to find it yourself. So, if you will step this way I will take you to the sorting room and you may look to your heart’s content.’

The man was outraged; he bellowed an expletive in Arabic and thumped the kitchen table with his fist. ‘What do you mean, I am obliged to find it? You are the broker, it’s your vault, they’re your keys, you must find it!’

‘No. You should have read the small print,’ said Devilskein with a mirthless smile. ‘But none of you ever do. This way please.’

The next thing Erin knew, Devilskein was shaking her. His hands were icy.

‘Wake up, scrawny child!’ he said. ‘You fell asleep and now you must go. Your people downstairs will start looking for you and I have a long night ahead of me.’

Erin got to her feet. Outside, stars had long since pushed the sun from the sky. She frowned when she saw that the time on the clock had not changed. Devilskein shoved the remaining Lemon Creams back into the packet, which he twisted at the top and handed to her. ‘Away with you!’ And find your soulmate little one! My immortality depends on it.

She was too drowsy to protest, even though she wanted to tell him to keep the biscuits, and more than that, she wanted to know how it was she had been sleeping all this time, which felt so terribly long. She realised her feet were bare.

‘Go on then.’ He handed her her shoes, ushered her out of the kitchen and towards the front door. ‘Go home and don’t come back.’ Or not until you’ve found that true love of yours.

Having slept, her eyes were accustomed to the dark and she could make out more of the entrance room than when she first came in. It was a small room, with uneven floors and six internal doors and it had a curious habit of expanding and contracting. ‘Is this room breathing?’ asked Erin, watching the walls rise and fall. It seemed as if they were standing inside the lungs of some beast. Erin rubbed her eyes. ‘No, of course not.’ She shook her head. ‘A room doesn’t breathe, does it?’

Devilskein said nothing, though he thought of a Japanese man who once said: ‘The body is the outer layer of the mind, as the cover is the outer layer of a book’. He smiled.

‘I don’t know why I feel so dizzy. I’m sorry I fell asleep.’ She slipped her feet into her sandals, struggling to fasten the buckle of her right shoe. ‘You really like shoes, don’t you?’ she said, finally unable to resist making at least some remark about the towers of shoeboxes.

Jerking his head at the front door, Devilskein grunted. ‘If you don’t leave now, I will become angry.’

‘No need for that,’ Erin said, abandoning the faulty clasp. She was going to reach for the door handle when she remembered something. ‘I had the strangest dreams. I was in a museum and then it became a train.’ She looked about disconcerted. ‘But it wasn’t exactly a train; it was rather like this room with six doors. And there was a different view from every door.’

‘Out!’ He pointed at the exit. ‘I have things to do.’

‘What things? What do you do?’

In the corridor a cat stalked a pair of pigeons.

Another growl gurgled in Devilskein’s throat. ‘Did I not say there would be no conversation? If you change the rules, I cannot be blamed for the consequences.’

Feeling more awake than before, Erin, who had never been timid and was by then quite used to Devilskein’s fearsome appearance, put her hand on her hip and asked, ‘What on earth are you talking about? What rules are you talking about?’

He clenched his fists behind his back. ‘Your friend warned you, and I warned you, but you are an insolent child.’

‘What friend? I have no friend, and quite frankly you are a very rude man.’

‘Man? What gives you that impression? My clothes – yes perhaps, they do bear a resemblance to the clothes of men.’ He smiled a ghastly smile and laughed a dreadful laugh. ‘Go before you see too much, before it is too late.’

Erin lost her courage, and with it the urge to ask questions. Without looking left or right again, she opened the door and departed from Devilskein and his strange world. The hunting cat in the corridor hissed; the pigeons flapped and scattered. Outside it was dark, much, much darker than when she’d gone in. The passage lights cast rays upon the cement floors of Van Riebeek Heights. A little distance ahead a heap moved, jolting mosquitoes and sand flies from their blood-rich drinks. As Erin approached, she realised it was Kelwyn. He looked up and rubbed his eyes. The predatory cat bared her teeth as Erin passed.

‘What were you doing in there?’ Kelwyn sneezed.

‘That’s none of your business.’

He stood up and rubbed a cramped muscle in his neck; he’d been sleeping at an awkward angle. ‘I thought I’d never see you again.’

‘Well, sorry to disappoint you.’ She marched past.

‘That’s no way to say thank you.’ He sneezed again – Erin was covered in dust.

‘I have no need to thank you.’

He scratched bites on his legs and scrambled to follow her down the stairs to their floor. ‘Oh yes you do,’ he checked his watch. ‘In half an hour I would have come in there to rescue you from the monster.’

‘He’s not a monster.’ She turned her startling eyes upon him: her irises began with a rim of black and progressed through emerald to all shades of green ending with a pale, dreamy jade around their pupils. ‘Mr Devilskein happens to make excellent tea and I was in no need of rescuing.’ She recalled Devilskein’s laugh and shuddered, but decided she would return to his apartment the following evening. ‘In fact, I’m meeting him again tomorrow and I’m going to bake scones. I promised I would.’

‘You’re insane!’ Kelwyn grabbed his fifteen-year-old head in exasperation. ‘You can’t go back there, that creature will kill you.’ And he didn’t want that, because even though she was infuriating, Kelwyn’s heart ached a bit for Erin and her proper posture, long neck and pale face garlanded over the cheeks and nose with a scattering of freckles, but what he wanted most was to fold her in a hug and tell her everything would work out, that she didn’t have to tell stories. He had a feeling about her, he couldn’t explain the feeling with any exactitude, but somehow he knew they were more than just unlikely neighbours.

Eyes blazing beneath fair eyebrows, Erin turned and glared at him. ‘Don’t call me that and don’t tell me what I can and can’t do.’

Kelwyn shrugged. ‘Okay, grumpy, if you must go back, I suppose you must, but I don’t think it’s a good idea.’

The luxury liner cruised further away, into the shark-filled waves; lamb sizzled in the cooking pots on the stove at Mama Africa. There were sirens in Long Street and music and laughter and cigarette smoke floated up from the bars and clubs.

Erin’s face contorted with fury. ‘What you think is irrelevant. You’re just… a stupid boy.’

He smiled, lopsided. ‘Is that the best you can do, Grumpy?’

She roared with frustration and pushed him aside. ‘You’re such an idiot.’ She ran to her aunt’s door and when Kate opened up, for the second time that day, Erin pushed past her unceremoniously, just as her aunt was saying, ‘I’ve been worried about you!’ and ran into her bedroom, slamming the door behind her. She threw herself down on her bed.

Kelwyn lingered outside. His legs were covered in bites, and mosquitoes followed eagerly for more of his sweet blood.

‘Where on earth have you two been?’ asked Aunt Kate.

Cockroaches scuffled; a full moon took possession of the sky; Kelwyn’s bare legs itched.

‘I saved Erin from a monster,’ Kelwyn said.

And Erin vaguely heard, and would have argued the point, but with her head on a soft, clean, but poorly ironed pillowcase, she was unable to fight the exhaustion that pulled her towards sleep and dreadful dreams.

Aunt Kate was saying something Erin couldn’t quite hear.

‘Everything is fine now,’ Kelwyn said, and it was in that moment that he realised he definitely had a crush on the girl with a traumatic past.