Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jazzybee Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

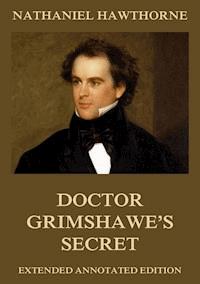

When Hawthorne died in 1864, he left in manuscript three unfinished romances which, when afterward published by his heirs, were given the arbitrary titles of Doctor Grimshawe's Secret, Septimius Felton, and The Dolliver Romance. Doctor Grimshawe's Secret represents Hawthorne's attempt to write an "English romance" out of his own experiences in England during his residence there from 1853 to 1858.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 482

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Doctor Grimshawe's Secret

Nathaniel Hawthorne

Contents:

Nathaniel Hawthorne – A Biographical Primer

Doctor Grimshawe's Secret

Preface

Chapter I

Chapter II.

Chapter III.

Chapter IV.

Chapter V.

Chapter VI.

Chapter VII.

Chapter VIII.

Chapter IX.

Chapter X.

Chapter XI.

Chapter XII.

Chapter XIII.

Chapter XIV.

Chapter XV.

Chapter XVI.

Chapter XVII.

Chapter XVIII.

Chapter XIX.

Chapter XX.

Chapter XXI.

Chapter XXII.

Chapter XXIII.

Chapter XXIV.

Chapter XXV.

Doctor Grimshawe's Secret, N. Hawthorne

Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck

86450 Altenmünster, Loschberg 9

Germany

ISBN:9783849641030

www.jazzybee-verlag.de

www.facebook.com/jazzybeeverlag

Nathaniel Hawthorne – A Biographical Primer

By Edward Everett Hale

American novelist: b. Salem, Mass., 4 July 1804; d. Plymouth, N. H., 19 May 1864. The founder of the family in America was William Hathorne (as the name was then spelled), a typical Puritan and a public man of importance. John, his son, was a judge, one of those presiding over the witchcraft trials. Of Joseph in the next generation little is said, but Daniel, next in decent, followed the sea and commanded a privateer in the Revolution, while his son Nathaniel, father of the romancer, was also a sea Captain. This pure New England descent gave a personal character to Hawthorne's presentations of New England life; when he writes of the strictness of the early Puritans, of the forests haunted by Indians, of the magnificence of the provincial days, of men high in the opinion of their towns-people, of the reaching out to far lands and exotic splendors, he is expressing the stored-up experience of his race. His father died when Nathaniel was but four and the little family lived a secluded life with his mother. He was a handsome boy and quite devoted to reading, by an early accident which for a time prevented outdoor games. His first school was with Dr. Worcester, the lexicographer. In 1818 his mother moved to Raymond, Me., where her brother had bought land, and Hawthorne went to Bowdoin College. He entered college at the age of 17 in the same class with Longfellow. In the class above him was Franklin Pierce, afterward 12th President of the United States. On being graduated in 1825 Hawthorne determined upon literature as a profession, but his first efforts were without success. ‘Fanshawe’ was published anonymously in 1828, and shorter tales and sketches were without importance. Little need be said of these earlier years save to note that they were full of reading and observation. In 1836 he edited in Boston the AmericanMagazine for Useful and Entertaining Knowledge, but gained little from it save an introduction to ‘The Token,’ in which his tales first came to be known. Returning to Salem he lived a very secluded life, seeing almost no one (rather a family trait), and devoted to his thoughts and imaginations. He was a strong and powerful man, of excellent health and, though silent, cheerful, and a delightful companion when be chose. But intellectually he was of a separated and individual type, having his own extravagances and powers and submitting to no companionship in influence. In 1837 appeared ‘Twice Told Tales’ in book form: in a preface written afterward Hawthorne says that he was at this time “the obscurest man of letters in America.” Gradually he began to be more widely received. In 1839 he became engaged to Miss Sophia Peabody, but was not married for some years. In 1838 he was appointed to a place in the Boston custom house, but found that he could not easily save time enough for literature and was not very sorry when the change of administration put him out of office. In 1841 was founded the socialistic community at Brook Farm: it seemed to Hawthorne that here was a chance for a union of intellectual and physical work, whereby he might make a suitable home for his future wife. It failed to fulfil his expectations and Hawthorne withdrew from the experiment. In 1842 he was married and moved with his wife to the Old Manse at Concord just above the historic bridge. Here chiefly he wrote the ‘Mosses of an Old Manse’ (1846). In 1845 he published a second series of ‘Twice Told Tales’; in this year also the family moved to Salem, where he had received the appointment of surveyor at the custom house. As before, official work was a hindrance to literature; not till 1849 when he lost his position could he work seriously. He used his new-found leisure in carrying out a theme that had been long in his mind and produced ‘The Scarlet Letter’ in 1850. This, the first of his longer novels, was received with enthusiasm and at once gave him a distinct place in literature. He now moved to Lenox, Mass., where he began on ‘The House of Seven Gables,’ which was published in 1851. He also wrote ‘A Wonder-Book’ here, which in its way has become as famous as his more important work. In December 1851 he moved to West Newton, and shortly to Concord again, this time to the Wayside. At Newton he wrote ‘The Blithedale Romance.’ Having settled himself at Concord in the summer of 1852, his first literary work was to write the life of his college friend, Franklin Pierce, just nominated for the Presidency. This done he turned to ‘Tanglewood Tales,’ a volume not unlike the ‘Wonder-Book.’ In 1853 he was named consul to Liverpool: at first he declined the position, but finally resolved to take this opportunity to see something of Europe. He spent four years in England, and then a year in Italy. As before, he could write nothing while an official, and resigned in 1857 to go to Rome, where he passed the winter, and to Florence, where he received suggestions and ideas which gave him stimulus for literary work. The summer of 1858 he passed at Redcar, in Yorkshire, where he wrote ‘The Marble Faun.’ In June 1860 he sailed for America, where he returned to the Wayside. For a time he did little literary work; in 1863 he published ‘Our Old Home,’ a series of sketches of English life, and planned a new novel, ‘The Dolliver Romance,’ also called ‘Pansie.’ But though he suffered from no disease his vitality seemed relaxed; some unfortunate accidents had a depressing effect, and in the midst of a carriage trip into the White Mountains with his old friend, Franklin Pierce, he died suddenly at Plymouth, N. H., early in the morning, 19 May 1864.

The works of Hawthorne consist of novels, short stories, tales for children, sketches of life and travel and some miscellaneous pieces of a biographical or descriptive character. Besides these there were published after his death extracts from his notebooks. Of his novels ‘The Scarlet Letter’ is a story of old New England; it has a powerful moral idea at bottom, but it is equally strong in its presentation of life and character in the early days of Massachusetts. ‘House of the Seven Gables’ presents New England life of a later date; there is more of careful analysis and presentation of character and more description of life and manners, but less moral intensity. ‘The Blithedale Romance’ is less strong; Hawthorne seems hardly to grasp his subject. It makes the third in what may be called a series of romances presenting the molding currents of New England life: the first showing the factors of religion and sin, the second the forces of hereditary good and evil, and the third giving a picture of intellectual and emotional ferment in a society which had come from very different beginnings. ‘Septimius Felton,’ finished in the main but not published by Hawthorne, is a fantastic story dealing with the idea of immortality. It was put aside by Hawthorne when he began to write ‘The Dolliver Romance,’ of which he completed only the first chapters. ‘Dr. Grimshaw's Secret’ (published in 1882) is also not entirely finished. These three books represent a purpose that Hawthorne never carried out. He had presented New England life, with which the life of himself and his ancestry was so indissolubly connected, in three characteristic phases. He had traced New England history to its source. He now looked back across the ocean to the England he had learned to know, and thought of a tale that should bridge the gulf between the Old World and the New. But the stories are all incomplete and should be read only by the student. The same thing may be said of ‘Fanshawe,’ which was published anonymously early in Hawthorne's life and later withdrawn from circulation. ‘The Marble Faun’ presents to us a conception of the Old World at its oldest point. It is Hawthorne's most elaborate work, and if every one were familiar with the scenes so discursively described, would probably be more generally considered his best. Like the other novels its motive is based on the problem of evil, but we have not precisely atonement nor retribution, as in his first two novels. The story is one of development, a transformation of the soul through the overcoming of evil. The four novels constitute the foundation of Hawthorne's literary fame and character, but the collections of short stories do much to develop and complete the structure. They are of various kinds, as follows: (1) Sketches of current life or of history, as ‘Rills from the Town Pump,’ ‘The Village Uncle,’ ‘Main Street,’ ‘Old News.’ These are chiefly descriptive and have little story; there are about 20 of them. (2) Stories of old New England, as ‘The Gray Champion,’ ‘The Gentle Boy,’ ‘Tales of the Province House.’ These stories are often illustrative of some idea and so might find place in the next set. (3) Stories based upon some idea, as ‘Ethan Brand,’ which presents the idea of the unpardonable sin; ‘The Minister's Black Veil,’ the idea of the separation of each soul from its fellows; ‘Young Goodman Brown,’ the power of doubt in good and evil. These are the most characteristic of Hawthorne's short stories; there are about a dozen of them. (4) Somewhat different are the allegories, as ‘The Great Stone Face,’ ‘Rappacini's Daughter,’ ‘The Great Carbuncle.’ Here the figures are not examples or types, but symbols, although in no story is the allegory consistent. (5) There are also purely fantastic developments of some idea, as ‘The New Adam and Eve,’ ‘The Christmas Banquet,’ ‘The Celestial Railroad.’ These differ from the others in that there is an almost logical development of some fancy, as in case of the first the idea of a perfectly natural pair being suddenly introduced to all the conventionalities of our civilization. There are perhaps 20 of these fantasies. Hawthorne's stories from classical mythology, the ‘Wonder-Book’ and ‘Tanglewood Tales,’ belong to a special class of books, those in which men of genius have retold stories of the past in forms suited to the present. The stories themselves are set in a piece of narrative and description which gives the atmosphere of the time of the writer, and the old legends are turned from stately myths not merely to children's stories, but to romantic fancies. Mr. Pringle in ‘Tanglewood Fireside’ comments on the idea: “Eustace,” he says to the young college student who had been telling the stories to the children, “pray let me advise you never more to meddle with a classical myth. Your imagination is altogether Gothic and will inevitably Gothicize everything that you touch. The effect is like bedaubing a marble statue with paint. This giant, now! How can you have ventured to thrust his huge disproportioned mass among the seemly outlines of Grecian fable?” “I described the giant as he appeared to me,” replied the student, “And, sir, if you would only bring your mind into such a relation to these fables as is necessary in order to remodel them, you would see at once that an old Greek has no more exclusive right to them than a modern Yankee has. They are the common property of the world and of all time” (“Wonder-Book,” p. 135). ‘Grandfather's Chair’ was also written primarily for children and gives narratives of New England history, joined together by a running comment and narrative from Grandfather, whose old chair had come to New England, not in the Mayflower, but with John Winthrop and the first settlers of Boston. ‘Biographical Stories,’ in a somewhat similar framework, tells of the lives of Franklin, Benjamin West and others. It should be noted of these books that Hawthorne's writings for children were always written with as much care and thought as his more serious work. ‘Our Old Home’ was the outcome of that less remembered side of Hawthorne's genius which was a master of the details of circumstance and surroundings. The notebooks give us this also, but the American notebook has also rather a peculiar interest in giving us many of Hawthorne's first ideas which were afterward worked out into stories and sketches.

One element in Hawthorne's intellectual make-up was his interest in the observation of life and his power of description of scenes, manners and character. This is to be seen especially, as has been said, in his notebooks and in ‘Our Old Home,’ and in slightly modified form in the sketches noted above. These studies make up a considerable part of ‘Twice Told Tales’ and ‘Mosses from an Old Manse,’ and represent a side of Hawthorne's genius not always borne in mind. Had this interest been predominant in him we might have had in Hawthorne as great a novelist of our everyday life as James or Howells. In the ‘House of Seven Gables’ the power comes into full play; 100 pages hardly complete the descriptions of the simple occupations of a single uneventful day. In Hawthorne, however, this interest in the life around him was mingled with a great interest in history, as we may see, not only in the stories of old New England noted above, but in the descriptive passages of ‘The Scarlet Letter.’ Still we have not, even here, the special quality for which we know Hawthorne. Many great realists have written historical novels, for the same curiosity that absorbs one in the affairs of everyday may readily absorb one in the recreation of the past. In Hawthorne, however, was another element very different. His imagination often furnished him with conceptions having little connection with the actual circumstances of life. The fanciful developments of an idea noted above (5) have almost no relation to fact: they are “made up out of his own head.” They are fantastic enough, but generally they are developments of some moral idea and a still more ideal development of such conceptions was not uncommon in Hawthorne. ‘Rappacini's Daughter’ is an allegory in which the idea is given a wholly imaginary setting, not resembling anything that Hawthorne had ever known from observation. These two elements sometimes appear in Hawthorne's work separate and distinct just as they did in his life: sometimes he secluded himself in his room, going out only after nightfall; sometimes he wandered through the country observing life and meeting with everybody. But neither of these elements alone produced anything great, probably because for anything great we need the whole man. The true Hawthorne was a combination of these two elements, with various others of personal character, and artistic ability that cannot be specified here. The most obvious combination between these two elements, so far as literature is concerned, between the fact of external life and the idea of inward imagination, is by a symbol. The symbolist sees in everyday facts a presentation of ideas. Hawthorne wrote a number of tales that are practically allegories: ‘The Great Stone Face’ uses facts with which Hawthorne was familiar, persons and scenes that he knew, for the presentation of a conception of the ideal. His novels, too, are full of symbolism. ‘The Scarlet Letter’ itself is a symbol and the rich clothing of Little Pearl, Alice's posies among the Seven Gables, the old musty house itself, are symbols, Zenobia's flower, Hilda's doves. But this is not the highest synthesis of power, as Hawthorne sometimes felt himself, as when he said of ‘The Great Stone Face,’ that the moral was too plain and manifest for a work of art. However much we may delight in symbolism it must be admitted that a symbol that represents an idea only by a fanciful connection will not bear the seriousness of analysis of which a moral idea must be capable. A scarlet letter A has no real connection with adultery, which begins with A and is a scarlet sin only to such as know certain languages and certain metaphors. So Hawthorne aimed at a higher combination of the powers of which he was quite aware, and found it in figures and situations in which great ideas are implicit. In his finest work we have, not the circumstance before the conception or the conception before the circumstance, as in allegory. We have the idea in the fact, as it is in life, the two inseparable. Hester Prynne's life does not merely present to us the idea that the breaking of a social law makes one a stranger to society with its advantages and disadvantages. Hester is the result of her breaking that law. The story of Donatello is not merely a way of conveying the idea that the soul which conquers evil thereby grows strong in being and life. Donatello himself is such a soul growing and developing. We cannot get the idea without the fact, nor the fact without the idea. This is the especial power of Hawthorne, the power of presenting truth implicit in life. Add to this his profound preoccupation with the problem of evil in this world, with its appearance, its disappearance, its metamorphoses, and we have a due to Hawthorne's greatest works. In ‘The Scarlet Letter,’ ‘The House of Seven Gables,’ ‘The Marble Faun,’ ‘Ethan Brand,’ ‘The Gray Champion,’ the ideas cannot be separated from the personalities which express them. It is this which constitutes Hawthorne's lasting power in literature. His observation is interesting to those that care for the things that he describes, his fancy amuses, or charms or often stimulates our ideas. His short stories are interesting to a student of literature because they did much to give a definite character to a literary form which has since become of great importance. His novels are exquisite specimens of what he himself called the romance, in which the figures and scenes are laid in a world a little more poetic than that which makes up our daily surrounding. But Hawthorne's really great power lay in his ability to depict life so that we are made keenly aware of the dominating influence of moral motive and moral law.

Doctor Grimshawe's Secret

Preface

A preface generally begins with a truism; and I may set out with the admission that it is not always expedient to bring to light the posthumous work of great writers. A man generally contrives to publish, during his lifetime, quite as much as the public has time or inclination to read; and his surviving friends are apt to show more zeal than discretion in dragging forth from his closed desk such undeveloped offspring of his mind as he himself had left to silence. Literature has never been redundant with authors who sincerely undervalue their own productions; and the sagacious critics who maintain that what of his own an author condemns must be doubly damnable, are, to say the least of it, as often likely to be right as wrong.

Beyond these general remarks, however, it does not seem necessary to adopt an apologetic attitude. There is nothing in the present volume which any one possessed of brains and cultivation will not be thankful to read. The appreciation of Nathaniel Hawthorne's writings is more intelligent and wide-spread than it used to be; and the later development of our national literature has not, perhaps, so entirely exhausted our resources of admiration as to leave no welcome for even the less elaborate work of a contemporary of Dickens and Thackeray. As regards "Doctor Grimshawe's Secret,"—the title which, for lack of a better, has been given to this Romance,—it can scarcely be pronounced deficient in either elaboration or profundity. Had Mr. Hawthorne written out the story in every part to its full dimensions, it could not have failed to rank among the greatest of his productions. He had looked forward to it as to the crowning achievement of his literary career. In the Preface to "Our Old Home" he alludes to it as a work into which he proposed to convey more of various modes of truth than he could have grasped by a direct effort. But circumstances prevented him from perfecting the design which had been before his mind for seven years, and upon the shaping of which he bestowed more thought and labor than upon anything else he had undertaken. The successive and consecutive series of notes or studies [Footnote: These studies, extracts from which will be published in one of our magazines, are hereafter to be added, in their complete form, to the Appendix of this volume.] which he wrote for this Romance would of themselves make a small volume, and one of autobiographical as well as literary interest. There is no other instance, that I happen to have met with, in which a writer's thought reflects itself upon paper so immediately and sensitively as in these studies. To read them is to look into the man's mind, and see its quality and action. The penetration, the subtlety, the tenacity; the stubborn gripe which he lays upon his subject, like that of Hercules upon the slippery Old Man of the Sea; the clear and cool common-sense, controlling the audacity of a rich and ardent imagination; the humorous gibes and strange expletives wherewith he ridicules, to himself, his own failure to reach his goal; the immense patience with which—again and again, and yet again—he "tries back," throwing the topic into fresh attitudes, and searching it to the marrow with a gaze so piercing as to be terrible;—all this gives an impression of power, of resource, of energy, of mastery, that exhilarates the reader. So many inspired prophets of Hawthorne have arisen of late, that the present writer, whose relation to the great Romancer is a filial one merely, may be excused for feeling some embarrassment in submitting his own uninstructed judgments to competition with theirs. It has occurred to him, however, that these undress rehearsals of the author of "The Scarlet Letter" might afford entertaining and even profitable reading to the later generation of writers whose pleasant fortune it is to charm one another and the public. It would appear that this author, in his preparatory work at least, has ventured in some manner to disregard the modern canons which debar writers from betraying towards their creations any warmer feeling than a cultured and critical indifference: nor was his interest in human nature such as to confine him to the dissection of the moral epidermis of shop-girls and hotel-boarders. On the contrary, we are presented with the spectacle of a Titan, baring his arms and plunging heart and soul into the arena, there to struggle for death or victory with the superb phantoms summoned to the conflict by his own genius. The men of new times and new conditions will achieve their triumphs in new ways; but it may still be worth while to consider the methods and materials of one who also, in his own fashion, won and wore the laurel of those who know and can portray the human heart.

But let us return to the Romance, in whose clear though shadowy atmosphere the thunders and throes of the preparatory struggle are inaudible and invisible, save as they are implied in the fineness of substance and beauty of form of the artistic structure. The story is divided into two parts, the scene of the first being laid in America; that of the second, in England. Internal evidence of various kinds goes to show that the second part was the first written; or, in other words, that the present first part is a rewriting of an original first part, afterwards discarded, and of which the existing second part is the continuation. The two parts overlap, and it shall be left to the ingenuity of critics to detect the precise point of junction. In rewriting the first part, the author made sundry minor alterations in the plot and characters of the story, which alterations were not carried into the second part. It results from this that the manuscript presents various apparent inconsistencies. In transcribing the work for the press, these inconsistent sentences and passages have been withdrawn from the text and inserted in the Appendix; or, in a few unimportant instances, omitted altogether. In other respects, the text is printed as the author left it, with the exception of the names of the characters. In the manuscript each personage figures in the course of the narrative under from three to six different names. This difficulty has been met by bestowing upon each of the dramatis personæ the name which last identified him to the author's mind, and keeping him to it throughout the volume.

The story, as a story, is complete as it stands; it has a beginning, a middle, and an end. There is no break in the narrative, and the legitimate conclusion is reached. To say that the story is complete as a work of art, would be quite another matter. It lacks balance and proportion. Some characters and incidents are portrayed with minute elaboration; others, perhaps not less important, are merely sketched in outline. Beyond a doubt it was the author's purpose to rewrite the entire work from the first page to the last, enlarging it, deepening it, adorning it with every kind of spiritual and physical beauty, and rounding out a moral worthy of the noble materials. But these last transfiguring touches to Aladdin's Tower were never to be given; and he has departed, taking with him his Wonderful Lamp. Nevertheless there is great splendor in the structure as we behold it. The character of old Doctor Grimshawe, and the picture of his surroundings, are hardly surpassed in vigor by anything their author has produced; and the dusky vision of the secret chamber, which sends a mysterious shiver through the tale, seems to be unique even in Hawthorne.

There have been included in this volume photographic reproductions of certain pages of the original manuscript of Doctor Grimshawe, selected at random, upon which those ingenious persons whose convictions are in advance of their instruction are cordially invited to try their teeth; for it has been maintained that Mr. Hawthorne's handwriting was singularly legible. The present writer possesses specimens of Mr. Hawthorne's chirography at various ages, from boyhood until a day or two before his death. Like the handwriting of most men, it was at its best between the twenty-fifth and the fortieth years of life; and in some instances it is a remarkably beautiful type of penmanship. But as time went on it deteriorated, and, while of course retaining its elementary characteristics, it became less and less easy to read, especially in those writings which were intended solely for his own perusal. As with other men of sensitive organization, the mood of the hour, a good or a bad pen, a ready or an obstructed flow of thought, would all be reflected in the formation of the written letters and words. In the manuscript of the fragmentary sketch which has just been published in a magazine, which is written in an ordinary commonplace-book, with ruled pages, and in which the author had not yet become possessed with the spirit of the story and characters, the handwriting is deliberate and clear. In the manuscript of "Doctor Grimshawe's Secret," on the other hand, which was written almost immediately after the other, but on unruled paper, and when the writer's imagination was warm and eager, the chirography is for the most part a compact mass of minute cramped hieroglyphics, hardly to be deciphered save by flashes of inspiration. The matter is not, in itself, of importance, and is alluded to here only as having been brought forward in connection with other insinuations, with the notice of which it seems unnecessary to soil these pages. Indeed, were I otherwise disposed, Doctor Grimshawe himself would take the words out of my mouth; his speech is far more poignant and eloquent than mine. In dismissing this episode, I will take the liberty to observe that it appears to indicate a spirit in our age less sceptical than is commonly supposed,—belief in miracles being still possible, provided only the miracle be a scandalous one.

It remains to tell how this Romance came to be published. It came into my possession (in the ordinary course of events) about eight years ago. I had at that time no intention of publishing it; and when, soon after, I left England to travel on the Continent, the manuscript, together with the bulk of my library, was packed and stored at a London repository, and was not again seen by me until last summer, when I unpacked it in this city. I then finished the perusal of it, and, finding it to be practically complete, I re-resolved to print it in connection with a biography of Mr. Hawthorne which I had in preparation. But upon further consideration it was decided to publish the Romance separately; and I herewith present it to the public, with my best wishes for their edification.

JULIAN HAWTHORNE.

NEW YORK, November 21, 1882.

Chapter I

A long time ago, [Endnote: 1] in a town with which I used to be familiarly acquainted, there dwelt an elderly person of grim aspect, known by the name and title of Doctor Grimshawe,[Endnote: 2] whose household consisted of a remarkably pretty and vivacious boy, and a perfect rosebud of a girl, two or three years younger than he, and an old maid-of-all-work, of strangely mixed breed, crusty in temper and wonderfully sluttish in attire. [Endnote: 3] It might be partly owing to this handmaiden's characteristic lack of neatness (though primarily, no doubt, to the grim Doctor's antipathy to broom, brush, and dusting-cloths) that the house—at least in such portions of it as any casual visitor caught a glimpse of—was so overlaid with dust, that, in lack of a visiting card, you might write your name with your forefinger upon the tables; and so hung with cobwebs that they assumed the appearance of dusky upholstery.

It grieves me to add an additional touch or two to the reader's disagreeable impression of Doctor Grimshawe's residence, by confessing that it stood in a shabby by-street, and cornered on a graveyard, with which the house communicated by a back door; so that with a hop, skip, and jump from the threshold, across a flat tombstone, the two children [Endnote: 4] were in the daily habit of using the dismal cemetery as their playground. In their graver moods they spelled out the names and learned by heart doleful verses on the headstones; and in their merrier ones (which were much the more frequent) they chased butterflies and gathered dandelions, played hide-and-seek among the slate and marble, and tumbled laughing over the grassy mounds which were too eminent for the short legs to bestride. On the whole, they were the better for the graveyard, and its legitimate inmates slept none the worse for the two children's gambols and shrill merriment overhead. Here were old brick tombs with curious sculptures on them, and quaint gravestones, some of which bore puffy little cherubs, and one or two others the effigies of eminent Puritans, wrought out to a button, a fold of the ruff, and a wrinkle of the skull-cap; and these frowned upon the two children as if death had not made them a whit more genial than they were in life. But the children were of a temper to be more encouraged by the good-natured smiles of the puffy cherubs, than frightened or disturbed by the sour Puritans.

This graveyard (about which we shall say not a word more than may sooner or later be needful) was the most ancient in the town. The clay of the original settlers had been incorporated with the soil; those stalwart Englishmen of the Puritan epoch, whose immediate ancestors had been planted forth with succulent grass and daisies for the sustenance of the parson's cow, round the low-battlemented Norman church towers in the villages of the fatherland, had here contributed their rich Saxon mould to tame and Christianize the wild forest earth of the new world. In this point of view—as holding the bones and dust of the primeval ancestor—the cemetery was more English than anything else in the neighborhood, and might probably have nourished English oaks and English elms, and whatever else is of English growth, without that tendency to spindle upwards and lose their sturdy breadth, which is said to be the ordinary characteristic both of human and vegetable productions when transplanted hither. Here, at all events, used to be some specimens of common English garden flowers, which could not be accounted for,—unless, perhaps, they had sprung from some English maiden's heart, where the intense love of those homely things, and regret of them in the foreign land, had conspired together to keep their vivifying principle, and cause its growth after the poor girl was buried. Be that as it might, in this grave had been hidden from sight many a broad, bluff visage of husbandman, who had been taught to plough among the hereditary furrows that had been ameliorated by the crumble of ages: much had these sturdy laborers grumbled at the great roots that obstructed their toil in these fresh acres. Here, too, the sods had covered the faces of men known to history, and reverenced when not a piece of distinguishable dust remained of them; personages whom tradition told about; and here, mixed up with successive crops of native-born Americans, had been ministers, captains, matrons, virgins good and evil, tough and tender, turned up and battened down by the sexton's spade, over and over again; until every blade of grass had its relations with the human brotherhood of the old town. A hundred and fifty years was sufficient to do this; and so much time, at least, had elapsed since the first hole was dug among the difficult roots of the forest trees, and the first little hillock of all these green beds was piled up.

Thus rippled and surged, with its hundreds of little billows, the old graveyard about the house which cornered upon it; it made the street gloomy, so that people did not altogether like to pass along the high wooden fence that shut it in; and the old house itself, covering ground which else had been sown thickly with buried bodies, partook of its dreariness, because it seemed hardly possible that the dead people should not get up out of their graves and steal in to warm themselves at this convenient fireside. But I never heard that any of them did so; nor were the children ever startled by spectacles of dim horror in the night-time, but were as cheerful and fearless as if no grave had ever been dug. They were of that class of children whose material seems fresh, not taken at second hand, full of disease, conceits, whims, and weaknesses, that have already served many people's turns, and been moulded up, with some little change of combination, to serve the turn of some poor spirit that could not get a better case.

So far as ever came to the present writer's knowledge, there was no whisper of Doctor Grimshawe's house being haunted; a fact on which both writer and reader may congratulate themselves, the ghostly chord having been played upon in these days until it has become wearisome and nauseous as the familiar tune of a barrel-organ. The house itself, moreover, except for the convenience of its position close to the seldom-disturbed cemetery, was hardly worthy to be haunted. As I remember it, (and for aught I know it still exists in the same guise,) it did not appear to be an ancient structure, nor one that would ever have been the abode of a very wealthy or prominent family;—a three-story wooden house, perhaps a century old, low-studded, with a square front, standing right upon the street, and a small enclosed porch, containing the main entrance, affording a glimpse up and down the street through an oval window on each side, its characteristic was decent respectability, not sinking below the boundary of the genteel. It has often perplexed my mind to conjecture what sort of man he could have been who, having the means to build a pretty, spacious, and comfortable residence, should have chosen to lay its foundation on the brink of so many graves; each tenant of these narrow houses crying out, as it were, against the absurdity of bestowing much time or pains in preparing any earthly tabernacle save such as theirs. But deceased people see matters from an erroneous—at least too exclusive—point of view; a comfortable grave is an excellent possession for those who need it, but a comfortable house has likewise its merits and temporary advantages. [Endnote: 5.]

The founder of the house in question seemed sensible of this truth, and had therefore been careful to lay out a sufficient number of rooms and chambers, low, ill-lighted, ugly, but not unsusceptible of warmth and comfort; the sunniest and cheerfulest of which were on the side that looked into the graveyard. Of these, the one most spacious and convenient had been selected by Doctor Grimshawe as a study, and fitted up with bookshelves, and various machines and contrivances, electrical, chemical, and distillatory, wherewith he might pursue such researches as were wont to engage his attention. The great result of the grim Doctor's labors, so far as known to the public, was a certain preparation or extract of cobwebs, which, out of a great abundance of material, he was able to produce in any desirable quantity, and by the administration of which he professed to cure diseases of the inflammatory class, and to work very wonderful effects upon the human system. It is a great pity, for the good of mankind and the advantage of his own fortunes, that he did not put forth this medicine in pill-boxes or bottles, and then, as it were, by some captivating title, inveigle the public into his spider's web, and suck out its gold substance, and himself wax fat as he sat in the central intricacy.

But grim Doctor Grimshawe, though his aim in life might be no very exalted one, seemed singularly destitute of the impulse to better his fortunes by the exercise of his wits: it might even have been supposed, indeed, that he had a conscientious principle or religious scruple—only, he was by no means a religious man—against reaping profit from this particular nostrum which he was said to have invented. He never sold it; never prescribed it, unless in cases selected on some principle that nobody could detect or explain. The grim Doctor, it must be observed, was not generally acknowledged by the profession, with whom, in truth, he had never claimed a fellowship; nor had he ever assumed, of his own accord the medical title by which the public chose to know him. His professional practice seemed, in a sort, forced upon him; it grew pretty extensive, partly because it was understood to be a matter of favor and difficulty, dependent on a capricious will, to obtain his services at all. There was unquestionably an odor of quackery about him; but by no means of an ordinary kind. A sort of mystery—yet which, perhaps, need not have been a mystery, had any one thought it worth while to make systematic inquiry in reference to his previous life, his education, even his native land—assisted the impression which his peculiarities were calculated to make. He was evidently not a New-Englander, nor a native of any part of these Western shores. His speech was apt to be oddly and uncouthly idiomatic, and even when classical in its form was emitted with a strange, rough depth of utterance, that came from recesses of the lungs which we Yankees seldom put to any use. In person, he did not look like one of us; a broad, rather short personage, with a projecting forehead, a red, irregular face, and a squab nose; eyes that looked dull enough in their ordinary state, but had a faculty, in conjunction with the other features, which those who had ever seen it described as especially ugly and awful. As regarded dress, Doctor Grimshawe had a rough and careless exterior, and altogether a shaggy kind of aspect, the effect of which was much increased by a reddish beard, which, contrary to the usual custom of the day, he allowed to grow profusely; and the wiry perversity of which seemed to know as little of the comb as of the razor.

We began with calling the grim Doctor an elderly personage; but in so doing we looked at him through the eyes of the two children, who were his intimates, and who had not learnt to decipher the purport and value of his wrinkles and furrows and corrugations, whether as indicating age, or a different kind of wear and tear. Possibly—he seemed so aggressive and had such latent heat and force to throw out when occasion called—he might scarcely have seemed middle-aged; though here again we hesitate, finding him so stiffened in his own way, so little fluid, so encrusted with passions and humors, that he must have left his youth very far behind him; if indeed he ever had any.

The patients, or whatever other visitors were ever admitted into the Doctor's study, carried abroad strange accounts of the squalor of dust and cobwebs in which the learned and scientific person lived; and the dust, they averred, was all the more disagreeable, because it could not well be other than dead men's almost intangible atoms, resurrected from the adjoining graveyard. As for the cobwebs, they were no signs of housewifely neglect on the part of crusty Hannah, the handmaiden; but the Doctor's scientific material, carefully encouraged and preserved, each filmy thread more valuable to him than so much golden wire. Of all barbarous haunts in Christendom or elsewhere, this study was the one most overrun with spiders. They dangled from the ceiling, crept upon the tables, lurked in the corners, and wove the intricacy of their webs wherever they could hitch the end from point to point across the window-panes, and even across the upper part of the doorway, and in the chimney-place. It seemed impossible to move without breaking some of these mystic threads. Spiders crept familiarly towards you and walked leisurely across your hands: these were their precincts, and you only an intruder. If you had none about your person, yet you had an odious sense of one crawling up your spine, or spinning cobwebs in your brain,—so pervaded was the atmosphere of the place with spider-life. What they fed upon (for all the flies for miles about would not have sufficed them) was a secret known only to the Doctor. Whence they came was another riddle; though, from certain inquiries and transactions of Doctor Grimshawe's with some of the shipmasters of the port, who followed the East and West Indian, the African and the South American trade, it was supposed that this odd philosopher was in the habit of importing choice monstrosities in the spider kind from all those tropic regions. [Endnote: 6.]

All the above description, exaggerated as it may seem, is merely preliminary to the introduction of one single enormous spider, the biggest and ugliest ever seen, the pride of the grim Doctor's heart, his treasure, his glory, the pearl of his soul, and, as many people said, the demon to whom he had sold his salvation, on condition of possessing the web of the foul creature for a certain number of years. The grim Doctor, according to this theory, was but a great fly which this spider had subtly entangled in his web. But, in truth, naturalists are acquainted with this spider, though it is a rare one; the British Museum has a specimen, and, doubtless, so have many other scientific institutions. It is found in South America; its most hideous spread of legs covers a space nearly as large as a dinner-plate, and radiates from a body as big as a door-knob, which one conceives to be an agglomeration of sucked-up poison which the creature treasures through life; probably to expend it all, and life itself, on some worthy foe. Its colors, variegated in a sort of ugly and inauspicious splendor, were distributed over its vast bulb in great spots, some of which glistened like gems. It was a horror to think of this thing living; still more horrible to think of the foul catastrophe, the crushed-out and wasted poison, that would follow the casual setting foot upon it.

No doubt, the lapse of time since the Doctor and his spider lived has already been sufficient to cause a traditionary wonderment to gather over them both; and, especially, this image of the spider dangles down to us from the dusky ceiling of the Past, swollen into somewhat uglier and huger monstrosity than he actually possessed. Nevertheless, the creature had a real existence, and has left kindred like himself; but as for the Doctor, nothing could exceed the value which he seemed to put upon him, the sacrifices he made for the creature's convenience, or the readiness with which he adapted his whole mode of life, apparently, so that the spider might enjoy the conditions best suited to his tastes, habits, and health. And yet there were sometimes tokens that made people imagine that he hated the infernal creature as much as everybody else who caught a glimpse of him. [Endnote: 7.]

Note 1.The MS. gives the following alternative openings: "Early in the present century"; "Soon after the Revolution"; "Many years ago."

Note 2.Throughout the first four pages of the MS. the Doctor is called "Ormskirk," and in an earlier draft of this portion of the romance, "Etheredge."

Note 3. Author's note.—"Crusty Hannah is a mixture of Indian and negro."

Note 4. Author's note.—"It is understood from the first that the children are not brother and sister.—Describe the children with really childish traits, quarrelling, being naughty, etc.—The Doctor should occasionally beat Ned in course of instruction."

Note 5.In order to show the manner in which Hawthorne would modify a passage, which was nevertheless to be left substantially the same, I subjoin here a description of this graveyard as it appears in the earlier draft: "The graveyard (we are sorry to have to treat of such a disagreeable piece of ground, but everybody's business centres there at one time or another) was the most ancient in the town. The dust of the original Englishmen had become incorporated with the soil; of those Englishmen whose immediate predecessors had been resolved into the earth about the country churches,—the little Norman, square, battlemented stone towers of the villages in the old land; so that in this point of view, as holding bones and dust of the first ancestors, this graveyard was more English than anything else in town. There had been hidden from sight many a broad, bluff visage of husbandmen that had ploughed the real English soil; there the faces of noted men, now known in history; there many a personage whom tradition told about, making wondrous qualities of strength and courage for him;—all these, mingled with succeeding generations, turned up and battened down again with the sexton's spade; until every blade of grass was human more than vegetable,—for an hundred and fifty years will do this, and so much time, at least, had elapsed since the first little mound was piled up in the virgin soil. Old tombs there were too, with numerous sculptures on them; and quaint, mossy gravestones; although all kinds of monumental appendages were of a date more recent than the time of the first settlers, who had been content with wooden memorials, if any, the sculptor's art not having then reached New England. Thus rippled, surged, broke almost against the house, this dreary graveyard, which made the street gloomy, so that people did not like to pass the dark, high wooden fence, with its closed gate, that separated it from the street. And this old house was one that crowded upon it, and took up the ground that would otherwise have been sown as thickly with dead as the rest of the lot; so that it seemed hardly possible but that the dead people should get up out of their graves, and come in there to warm themselves. But in truth, I have never heard a whisper of its being haunted."

Note 6. Author's note.—"The spiders are affected by the weather and serve as barometers.—It shall always be a moot point whether the Doctor really believed in cobwebs, or was laughing at the credulous."

Note 7. Author's note.—"The townspeople are at war with the Doctor.—Introduce the Doctor early as a smoker, and describe.—The result of Crusty Hannah's strangely mixed breed should be shown in some strange way.—Give vivid pictures of the society of the day, symbolized in the street scenes."

Chapter II.

Considering that Doctor Grimshawe, when we first look upon him, had dwelt only a few years in the house by the graveyard, it is wonderful what an appearance he, and his furniture, and his cobwebs, and their unweariable spinners, and crusty old Hannah, all had of having permanently attached themselves to the locality. For a century, at least, it might be fancied that the study in particular had existed just as it was now; with those dusky festoons of spider-silk hanging along the walls, those book-cases with volumes turning their parchment or black-leather backs upon you, those machines and engines, that table, and at it the Doctor, in a very faded and shabby dressing-gown, smoking a long clay pipe, the powerful fumes of which dwelt continually in his reddish and grisly beard, and made him fragrant wherever he went. This sense of fixedness—stony intractability—seems to belong to people who, instead of hope, which exalts everything into an airy, gaseous exhilaration, have a fixed and dogged purpose, around which everything congeals and crystallizes. [Endnote: 1] Even the sunshine, dim through the dustiness of the two casements that looked upon the graveyard, and the smoke, as it came warm out of Doctor Grimshawe's mouth, seemed already stale. But if the two children, or either of them, happened to be in the study,—if they ran to open the door at the knock, if they came scampering and peeped down over the banisters,—the sordid and rusty gloom was apt to vanish quite away. The sunbeam itself looked like a golden rule, that had been flung down long ago, and had lain there till it was dusty and tarnished. They were cheery little imps, who sucked up fragrance and pleasantness out of their surroundings, dreary as these looked; even as a flower can find its proper perfume in any soil where its seed happens to fall. The great spider, hanging by his cordage over the Doctor's head, and waving slowly, like a pendulum, in a blast from the crack of the door, must have made millions and millions of precisely such vibrations as these; but the children were new, and made over every day, with yesterday's weariness left out.

The little girl, however, was the merrier of the two. It was quite unintelligible, in view of the little care that crusty Hannah took of her, and, moreover, since she was none of your prim, fastidious children, how daintily she kept herself amid all this dust; how the spider's webs never clung to her, and how, when—without being solicited—she clambered into the Doctor's arms and kissed him, she bore away no smoky reminiscences of the pipe that he kissed continually. She had a free, mellow, natural laughter, that seemed the ripened fruit of the smile that was generally on her little face, to be shaken off and scattered abroad by any breeze that came along. Little Elsie made playthings of everything, even of the grim Doctor, though against his will, and though, moreover, there were tokens now and then that the sight of this bright little creature was not a pleasure to him, but, on the contrary, a positive pain; a pain, nevertheless, indicating a profound interest, hardly less deep than though Elsie had been his daughter.

Elsie did not play with the great spider, but she moved among the whole brood of spiders as if she saw them not, and, being endowed with other senses than those allied to these things, might coexist with them and not be sensible of their presence. Yet the child, I suppose, had her crying fits, and her pouting fits, and naughtiness enough to entitle her to live on earth; at least crusty Hannah often said so, and often made grievous complaint of disobedience, mischief, or breakage, attributable to little Elsie; to which the grim Doctor seldom responded by anything more intelligible than a puff of tobacco-smoke, and, sometimes, an imprecation; which, however, hit crusty Hannah instead of the child. Where the child got the tenderness that a child needs to live upon, is a mystery to me; perhaps from some aged or dead mother, or in her dreams; perhaps from some small modicum of it, such as boys have, from the little boy; or perhaps it was from a Persian kitten, which had grown to be a cat in her arms, and slept in her little bed, and now assumed grave and protective airs towards her former playmate. [Endnote: 2.]

The boy, [Endnote: 3] as we have said, was two or three years Elsie's elder, and might now be about six years old. He was a healthy and cheerful child, yet of a graver mood than the little girl, appearing to lay a more forcible grasp on the circumstances about him, and to tread with a heavier footstep on the solid earth; yet perhaps not more so than was the necessary difference between a man-blossom, dimly conscious of coming things, and a mere baby, with whom there was neither past nor future. Ned, as he was named, was subject very early to fits of musing, the subject of which—if they had any definite subject, or were more than vague reveries—it was impossible to guess. They were of those states of mind, probably, which are beyond the sphere of human language, and would necessarily lose their essence in the attempt to communicate or record them. The little girl, perhaps, had some mode of sympathy with these unuttered thoughts or reveries, which grown people had ceased to have; at all events, she early learned to respect them, and, at other times as free and playful as her Persian kitten, she never in such circumstances ventured on any greater freedom than to sit down quietly beside him, and endeavor to look as thoughtful as the boy himself.

Once, slowly emerging from one of these waking reveries, little Ned gazed about him, and saw Elsie sitting with this pretty pretence of thoughtfulness and dreaminess in her little chair, close beside him; now and then peeping under her eyelashes to note what changes might come over his face. After looking at her a moment or two, he quietly took her willing and warm little hand in his own, and led her up to the Doctor.

The group, methinks, must have been a picturesque one, made up as it was of several apparently discordant elements, each of which happened to be so combined as to make a more effective whole. The beautiful grave boy, with a little sword by his side and a feather in his hat, of a brown complexion, slender, with his white brow and dark, thoughtful eyes, so earnest upon some mysterious theme; the prettier little girl, a blonde, round, rosy, so truly sympathetic with her companion's mood, yet unconsciously turning all to sport by her attempt to assume one similar;—these two standing at the grim Doctor's footstool; he meanwhile, black, wild-bearded, heavy-browed, red-eyed, wrapped in his faded dressing-gown, puffing out volumes of vapor from his long pipe, and making, just at that instant, application to a tumbler, which, we regret to say, was generally at his elbow, with some dark-colored potation in it that required to be frequently replenished from a neighboring black bottle. Half, at least, of the fluids in the grim Doctor's system must have been derived from that same black bottle, so constant was his familiarity with its contents; and yet his eyes were never redder at one time than another, nor his utterance thicker, nor his mood perceptibly the brighter or the duller for all his conviviality. It is true, when, once, the bottle happened to be empty for a whole day together, Doctor Grimshawe was observed by crusty Hannah and by the children to be considerably fiercer than usual: so that probably, by some maladjustment of consequences, his intemperance was only to be found in refraining from brandy.

Nor must we forget—in attempting to conceive the effect of these two beautiful children in such a sombre room, looking on the graveyard, and contrasted with the grim Doctor's aspect of heavy and smouldering fierceness—that over his head, at this very moment, dangled the portentous spider, who seemed to have come down from his web aloft for the purpose of hearing what the two young people could have to say to his patron, and what reference it might have to certain mysterious documents which the Doctor kept locked up in a secret cupboard behind the door.

"Grim Doctor," said Ned, after looking up into the Doctor's face, as a sensitive child inevitably does, to see whether the occasion was favorable, yet determined to proceed with his purpose whether so or not,—"Grim Doctor, I want you to answer me a question."

"Here's to your good health, Ned!" quoth the Doctor, eying the pair intently, as he often did, when they were unconscious. "So you want to ask me a question? As many as you please, my fine fellow; and I shall answer as many, and as much, and as truly, as may please myself!"

"Ah, grim Doctor!" said the little girl, now letting go of Ned's hand, and climbing upon the Doctor's knee, "'ou shall answer as many as Ned please to ask, because to please him and me!"