Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Durango is an adventure story about the great October cattle drive of Tubberlick. Set in rural Ireland during the Second World War, this novel features the themes of love, sex, money and betrayal. Durango has been produced as a film starring Brenda Fricker, Patrick Bergin and Pat Laffin.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 510

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1992

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To Noel Pearson

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

http://twitter.com/IrishPublisher

http://www.facebook.com/mercier.press

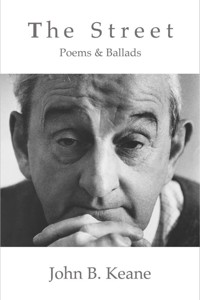

© John B. Keane 1991

ISBN: 978 1 85635 001 3

Epub ISBN: 978 1 7811 549 1

Mobi ISBN: 978 1 7811 550 7

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly

One

THE IDEA WAS MARK Doran’s and throughout the years that followed he never grew tired of reminding anybody who would listen that it occurred to him on his way homewards from the quarterly cattle and pig fair in the village of Tubberlick.

It was towards the end of March. Stars twinkled in the evening sky and there was a mild twinge of frost in the air.

He drew rein on his grey mare and slid to the roadway, staggering backwards as he did but managing to maintain his balance, albeit with some difficulty. He held firmly on to the mare’s tail as he composed himself. Planting his feet firmly apart he shook his curly head to dispel the drunkenness. Well-knit, spare and classically handsome, not his but a general female estimation, he loosened the tweed tie to which he would never become accustomed. For several minutes he inhaled the sobering night air, each breath deeper than the one preceding as his grogginess receded.

‘Too much porter girl,’ he explained to the mare. For her part she moved inwards to the green margin of the roadway and sampled a mouthful of the fresh grass which had sprung up abundantly over the previous fine days. Mark Doran undid his flies and released his plentiful waters through the third and fourth bars of the rust-covered gate where he had stopped so often in the past. The mare, now in her tenth year, champed contentedly as she moved slowly along the narrow sward.

Mark Doran absently secured his flies and leaned on the uppermost bar of the gate. In the adjoining hills the smoke ascended in rakish plumes from the cottages and farmhouses whose lights dotted the landscape. There was no sound to be heard saving the mare’s incisive cropping, now growing fainter as she moved further away from the gate. Mark Doran located his watch in a coat pocket. Six forty-five. Barring a calamity he should arrive home by seven. Then he would eat the boiled bacon, cabbage and potatoes which always confronted him on the kitchen table, steaming and savoury whenever he returned ravenous from the public houses of Tubberlick. The slobber trickled down the sides of his mouth at the prospect. He could see his mother sitting by the fire, a fork in her hand, alert to his every need, ready to coil the juicy cabbage in the skillet around the fork prongs or to impale a choice sliver of streaky bacon whenever the contents of his plate ran down. There wasn’t a woman in the hills could prepare cabbage like his mother.

‘Whoa girl!’ he called gently to the mare as he turned her back towards the gate. Lodging a left hand on her withers he drew her close to the gate pier. Placing his right hand atop the pier he swung into the saddle and bent over her chest to retrieve the reins.

It was precisely at the moment when he turned her that the idea came to him. Privately he always regarded it as more than just an idea. In his considered opinion inspiration seemed to be a fairer assessment.

In Tubberlick that day the talk in the pubs had been of a Second World War. There had been no great sense of alarm. The local papers had carried a story that conscription was being introduced in Britain.

Czechoslovakia had already been annexed by Germany and a mutual assistance pact between Britain, France and Poland had been ratified in its wake. There were other ominous rumblings from Italy so that it was no trouble for the more astute observers in Tubberlick to deduce that a large scale war in Europe was inevitable.

‘And if there’s war in Europe,’ the forecast came from the proprietor of McCarthy’s public house in Tubberlick where Mark Doran had spent most of his day, ‘the price of cattle and pigs will soar.’

Word of Vester McCarthy’s widely respected prognostications may or may not have reached the ears of the five cattle buyers in attendance at the Tubberlick quarterly fair. Certainly they were not reflected in the inexplicably low prices being offered for the wide variety of cattle on offer from frisky calves to venerable Roscreas. The latter was the name given to old cows whose usefulness had been terminated by age and who ended their days in the cannery in the far off town of Roscrea.

Mark Doran had long suspected the visiting buyers of being part of a ring and his suspicions were reinforced by the fact that cattle prices in Tubberlick were always a fraction behind those in other villages of the countryside. The trouble was that the villages in question were too far distant, the nearest ten and the furthest fifteen miles. Tubberlick on the other hand was only five miles from Mark Doran’s farmstead. The nearest cattle wagons were at Trallock Station almost forty miles away.

‘Cattle jobbers have to live too,’ his mother would say whenever he voiced his dissatisfaction after a frustrating day of haggling at the quarterly fair. She enjoyed in particular the calf dealers with their outsize horse-rails who called to the door. They brought news from faraway places as well as more intimate and often sensational disclosures from the less forthcoming of her immediate neighbours. Such revelations, false or true, had considerable trade value at mealtimes and even during sale negotiations. Mark himself showed little interest in these travellers’ tales but he listened nevertheless.

‘Whoa, whoa!’ he called to the mare. Dutifully she drew to a leisurely halt. Sobering by the minute Mark sat alert in his saddle and waited. In the distance behind him there arose the sound of discordant singing. He smiled to himself. It could only be the Mullanney brothers Tom and Jay in the horse-rail. Their father would be fast asleep on a bag of hay on the floor of this rickety conveyance, senseless from the day-long session of drinking which had begun at noon, the precise time he had received payment for the five calves which they had transported to Tubberlick shortly after daybreak.

Mark also had calves but he had decided against offering them for sale in Tubberlick. He would try elsewhere later in the year, much later, if his freshly-born idea should materialise. He would keep it to himself for awhile, let it simmer, see how he might feel on the morrow or during the weeks ahead.

Mark had found, after his father’s death two years before, that there were few places to turn when he wanted practical advice about holding or releasing his stock. He had found that it was wiser to wait, not always, but generally. Once he had waited too long and paid the price when the bottom fell out of the in-calf market because of oversupply. Things were always changing in the cattle world, sometimes imperceptibly, sometimes suddenly. Occasionally it was possible to make a fairly accurate prediction but there were no killings. The biggest bonus a producer might expect was a marginal increase on the market prices of the previous week.

He slackened the rein so that the mare might again address herself to the green margin. While she munched he waited. The singing had stopped. The brothers were arguing now, loud expletives shattering the benign silence of the bright March night. The stars still twinkled undismayed and the full moon, unaffected by cloud, shone serenely on blasphemous and pious alike as hair-raising threats, fiercely mouthed, erupted in turn from the approaching Mullanneys. To those who were not acquainted with their temperaments the Mullanneys represented extreme physical danger when their tempers ran high. Their acquaintances knew differently.

Nonie Doran, Mark’s mother, summed it up accurately when she heard an account of one of the fiercest fights to have taken place in the Mullanney household. Mother, father, brothers and sisters had all been involved and such were the scars borne by the menfolk after the affray that no male member of the family attended Sunday Mass for several weeks. Only Tom, the oldest was possessed of the gumption to present himself at the creamery with the milk supply, morning after morning, while his father and brothers wilted under their self-imposed incarceration.

‘They’re like the tinkers,’ Mark Doran’s mother Nonie had commented. ‘They’ll only fight amongst themselves.’

This wasn’t quite accurate. While it was true to say that they preferred to fight amongst themselves it would also be true to say that they were not above fighting with others. After their fights there were no recriminations for long periods but then a member of the clan would recall a particularly shifty blow or kick during a previous engagement and soon the fists would be flying. There was no resorting to weapons and no kicking while a combatant was on the ground.

‘Night boys!’ Mark called as he drew on the rein and rode alongside the brothers. Curled up on his hay-bag, on the floor of the cart, lay the sleeping form of the father of the family, old Haybags Mullanney. It was a truly profound sleep of the variety that can only be induced by whiskey and from which there is no waking until the participant has snorted and snored his way back to sobriety.

‘Who’s out there?’ The question came from Tom Mullanney.

‘It’s me, Mark Doran,’ Mark replied.

The disclosure was greeted with wild whoops of delight.

It was as though they hadn’t seen him for years. They relapsed immediately into a high-pitched, unsustainable song. At its conclusion Mark posed a question which he dared not ask in Tubberlick while Haybags was within earshot. Drunk as the brothers seemed to be they suddenly displayed an uncharacteristic caution at the mention of prices.

A whispered exchange took place. The last thing they wanted to do was to adopt a churlish attitude towards a neighbour and proven friend. Mark waited, uneasily. He had qualms about asking in the first place.

‘He didn’t tell us the exact amount mind you,’ Tom Mullanney replied after awhile, indicating the sleeping form at his feet, ‘but what he did say was that they made more than he expected.’

Mark Doran knew that he should not have asked in the first place. His mother might say that it was none of his business. He saw the whole matter in another light. The cloak of secrecy which his neighbours insisted in drawing over cattle prices would always militate against their chances of securing just prices for their stock. He knew the shame and degradation he himself had experienced when he was forced to sell cattle at less than their value. He fully understood the reluctance shown by the Mullanney brothers when his curiosity got the better of him. They were too proud to admit that they should have received more and ashamed to admit that they might have been duped. This was the common attitude all over the countryside. Nevertheless, he decided to probe further.

‘How much did he get the last time, do you remember?’

Any other question, personal or otherwise, would have elicited an immediate answer from the brothers.

Instead of a response, however, there followed an uneasy silence. It remained thus for several minutes as the cavalcade proceeded on its sluggish way homeward.

***

IT WAS THE SAME with bonhams and pigs, Mark thought. At the market in Tubberlick, buying and selling were conducted in confessional whispers. At the end of the day there was no means by which one could arrive at an average price. Consequently, there was no method of assessing loss or profit.

Imported maize ground into meal was the basic ingredient in the pig fattening process. It was also used, mixed with flour, in the baking of griddle bread. A griddlesized disc of dough, flattened by a rolling pin, was cut diagonally into four quarters or pointers as they were called in the hill country and baked on both sides on an iron griddle over an open fire of peat coals. Sliced down the middle and liberally smeared with home produced, salted butter, the yellow meal pointer was the most popular and palatable of all the baked produce common to the hill country.

‘Oh for a pointer of my mother’s griddle bread with the fresh butter melting on its top!’ was the plaint of many a farflung exile when confronted with less salubrious fare in restaurant or boarding house.

Once while Mark Doran was visiting an elderly granduncle, Joss the Badger Doran, in the inner hills the whole question of pig profits received an airing.

‘I swear to you,’ said the old man as he sat hunched over the hearth, ‘I never made a copper profit out of pigs.’

‘Why fatten them so?’ Mark had asked.

‘What other way is there of saving a bit of money?’ the old man had replied.

‘And what about profit?’ Mark had enquired.

‘I have no doubt there are some who manage to make profit,’ the old man had countered, ‘but all I ever found was the bare return for my investment when the time for selling came round. You must allow too for the pig you’ll lose. Have you thought of that? The nearest vet is twenty two miles away and you have to pay for his car as well as his services so I never bothered with vets. I know. I know,’ the old man had continued, ‘skimp on the vet and you lose more in the long run.’

As well as the yellow meal, fistfuls of pollard and bran were also added to the pig food. The cost of such ingredients was easily totted.

‘But then,’ asked Mark’s granduncle, ‘how do you put a price on home produced feed like potatoes and cabbage and the occasional turnip? Riddle me that my boy and I’ll pass you for a scholar.’

There was a good deal of truth in what the old man had said. His wife was equally vocal but would seem to be the better economist.

‘What ye forget,’ said she, ‘is that all bar the cows are fed out of the pigs’ mess. Turkey, hen, duck and goose, all gets their share and that’s where the profit is.’

‘I’m taking all that into the reckoning and maybe there’s something to what you say,’ the old man was always conciliatory when refuting his spouse.

‘You’d be setting the potatoes anyway,’ she continued as she drew upon the butt of a Woodbine, ‘and what great cost is a few bags extra of seed potatoes?’

‘Are you forgetting cabbage?’ the old man asked.

‘Indeed I’m not,’ she was quick to reply, ‘for cabbage does not come into it.’

‘Doesn’t come into it,’ he scoffed, ‘and pray where does all the cabbage our pigs does be eatin’ come from?’

‘You’re talking about the outside leaves now,’ she reminded him, ‘and not about the body or the heart. You’re talking about rough leaves that humans won’t stomach, big coarse leaves that’s of no use to anyone saving the pig or the cow. Aren’t my poor paws blistered from chopping them same leaves. The cabbage and the spud is more than threequarters of the pig’s diet and where are you leaving the waste from the kitchen table? The pig will do for that. The pig isn’t choosy. The pig will do for anything.’

Mark was forced to concede that it was a system suited to the small producer. Production on a larger scale was a gamble, often dangerous. If what the old woman said was true, and Mark would not deny that most of it was, then the pig was subsidising the hen and the turkey, two vital sources of income for the hill farmers, the fattened turkeys for the Christmas tables of town and city dwellers and the weekly lay of eggs to barter for flour, tea, sugar, tobacco and all the other household requirements with the occasional luxury such as a pot of jam or a barm brack.

The turkey money, which came once a year a few weeks before Christmas, was traditionally spent on the purchase of clothes and goodies for the Christmas proper, clothes in this instance to mean bibs and underclothes for the females of the household and socks or caps for the menfolk. Heavy clothes were another undertaking financed by the last cattle sales of the year at the Tubberlick quarterly fair near the end of October. Mark Doran was obliged to agree that pigs were profit making provided that there was no ill luck and provided that a fair price was assured. The likelihood of the latter happening was the exception rather than the rule unless the producer was presented with access to bigger markets. He never denied that a frugal living might be wrought from the average hill farm but only by dint of hard work, average luck and an able woman in the background. Without the last the struggle for survival would be unbearable.

***

MARK WAS ROUSED FROM his reverie by the argument. Once again he drew rein. The Mullanney brothers had alighted from the rail and were squaring off preparatory to a bout of fisticuffs on the roadway. The horse, a powerful bay gelding of six years stood idly by, well used to the tantrums of his volatile passengers while the father of the combatants slept blissfully on. Had he been astir and able to move he might well have challenged the winner. Even in his supine state it was clear to see that he was an outsized man. Haybags was never known to use his fists. Rather would he seize an opponent by the lapels or shirt front and shake the victim till the teeth rattled in his head. Another tactic of his was to run at his foes, hobnailed boots clattering, much like a war horse. Resignedly Mark Doran turned the mare and rode to where the brothers stood facing each other, their faces taut, their fists clenched, their eyes wild and bloodshot. Mark dismounted and looked from one to the other and then into the horse-rail. It would be difficult, he told this to himself, to imagine a more bizarre scene. The brothers ignored his arrival and were now involved in some orthodox feinting, feeling each other out, not that there was any need. Neither was able to remember the number of occasions in which they had been similarly involved since they were children.

‘Now boys!’ Mark moved between them, hands elevated, palms extended, ‘there’s no call for this, no call at all!’ His words had little effect.

‘Keep out of it,’ he was warned by each in turn. Then predictably for some reason best known to themselves they decided to opt for a wrestling contest rather than a fist fight. One moment they were sparring like gentlemen and the next they were rolling over on the roadway ending up under the gelding’s legs. The creature stood impassively as ever while the brothers extricated themselves, one at either side of the cart. Tom, the more eager to resume where they had left off, vaulted over the back shafts and leaped on his brother’s back before he could rise from the roadway.

Bucking like a bronco Jay threw his older brother out over his head and landed him, without apparent hurt, on the grassy margin.

‘Quiet!’ Mark called loudly and raised a hand. Sitting on his behind on the grass Tom Mullanney, temporarily winded, made no attempt to rise. His brother Jay turned to look in the direction from which the sounds were coming.

‘Stragglers from the fair,’ Mark extended a hand to Tom and brought him to his feet.

‘Into the car now before we’re the talk of the countryside.’

‘We’re that as it is,’ Jay Mullanney threw back as he climbed the rail.

Mark remounted hurriedly and soon the party was on its way once more.

‘What was that all about?’ Mark asked.

‘You and your bloody prices!’ came the terse reply from Jay Mullanney. ‘I was for telling and this fellow wasn’t.’

‘I was just curious,’ Mark tried to sound disinterested. ‘I had thought to bring some of my own calves today but I decided I’d check the prices first.’

‘Ours didn’t do very well,’ Jay Mullanney admitted, ‘back ten shillings a head on this time last year.’

‘Amen’t I the lucky man then I didn’t take them to Tubberlick,’ Mark said, trying hard to conceal his delight and more importantly the fact that his presentiments concerning the Tubberlick prices had proved accurate. His only business at the fair had been as an onlooker. A watching brief was what I had he told himself happily. He was sorry for the Mullanneys but then they didn’t have to sell. Theirs was a substantial farm, soggy maybe in some of its more level fields but with the carrying power of twenty-two milch cows, two horses and forty or more assorted dry stock consisting of store bullocks, fat heifers, heifers and weanlings. On top of that Mark never recalled a time when there hadn’t been a score of pigs fattening and a sow farrowing. So why sell he asked himself? An outing, of course, a day on the liquor to rouse the brain and shake off the cramps of winter, an escape from the house and outhouses until the blooms of spring brightened the meadows. Partly this was one of the reasons he himself had gone to Tubberlick. All of his neighbours admitted as much to themselves. They offered different excuses to their womenfolk, those of them who considered it expedient. Others, like Mark, retained their sucky calves and offered them at the October fairs in Tubberlick and other villages as weanlings. Somehow there was always a market for weanlings. Mark put it down to the high incidence of losses in calves in the early spring and summer.

Mark would attend several fairs between now and the final October fair at Tubberlick. Mostly he would interest himself in prices but if he saw what he believed to be a bargain he would not hesitate about purchasing. The farm was never short of grass between the months of April and October. Despite the death of his father, a shrewd and perceptive farmer, Mark began to see his own function in a clearer light. He regarded himself as an innovator and a speculator and despite the fact that he hadn’t a great deal to show for his enterprise he was learning every day and soon, very soon, his investments would begin to realise themselves. The great idea which visited him after he had drenched the grasses through the iron gate was not conceived purely by chance. It was the culmination of much profound thought and observation as well as seemingly fruitless travel through the numerous villages of the hill country that inspired the vision. That was the word that had escaped him since the revelation at the iron gate. He would, however, keep the vision to himself for awhile yet. He would need to add more body to it first and maybe discuss it discreetly with somebody who wasn’t given to loose talk, a man with the requisite knowledge and experience to weigh its merits.

‘Luckily for me,’ said Mark out of hearing of the Mullanneys, ‘I know such a man.’

Who else but his granduncle Joss the Badger! No better man to sift the chaff and point out the pitfalls and yet never a man to ignore the advantages. Mark resolved there and then that he would visit the old man before Easter. There was a small thatched pub a mile or so from the Badger’s dwelling. They had drunk there together many a time when Mark’s father was alive but then there seemed to be time for visiting, time for so many things. He would take the mare, put the old man in the saddle and sit behind him on the mare’s haunches maintaining a grip on the old man’s coat tails in such a way that neither of them would come to grief, not even when they were returning from the pub in the early hours of the morning.

He would spend the night with the old couple. His mother would handle the cows without difficulty even though the yield would have improved substantially by then. She could have one of the Mullanney girls down to help. She never grew tired of expressing her admiration for their willingness to work.

‘And there’s many a smart buck,’ she would say pointedly to nobody in particular, ‘who might travel farther and fare worse.’

As usual she had been telling the truth. Fight they might amongst themselves but shirk never! In the meadow, the bog or the gardens, the boys were capable of putting the best to shame. Jay Mullanney was talking now.

‘Come up with us for an hour,’ came the expected invitation, ‘we’ll have a game of cards after we eat. We’ll cheat the girls and you can help us unload our cargo.’

Mark considered the invitation before declining. It was a warm and generous household if explosive at times. The girls were buxom, robust, and playful although not Annie. Annie was the youngest and even if she took her mother’s side in every argument she was the most reasonable and effective when it became necessary to call a truce at the height of a disturbance. At sixteen she was dark eyed and sallow but pretty, very pretty in a childish way. Although Mark never failed to notice the more obvious advantages of the other sisters, the sonsy charms, the well defined buttocks and bosoms which often kept him awake nights and conversely helped him to sleep at the height of his fantasies it was to Annie he would always turn when he visited.

If she were studying he would sit beside her and pretend to be interested in what she was doing or if she was near the fire he would always find a place by her side. Nobody minded, least of all Annie. The other sisters realised that he was simply seeking refuge with the least dangerous member of the household’s females. The relationship was filled with banter and everybody saw it as harmless, more like a brother and sister situation than anything else, Mark the protective, overseeing element of the liaison and Annie the girl child in need of fraternal protection. If he sat near one of the older girls it would be a far more serious matter out of which anything might be read and out of which might emerge the most dangerous complications.

‘Come on,’ Jay was appealing now, ‘for the bare hour only.’

‘No but thanks,’ Mark explained how it had hardly been fair to leave his mother on her own since early morning with stock to feed and cows to milk.

‘Before the end of the week,’ he promised. He dismounted from the mare and bade the brothers to take care with their father. It had taken the pair and two other grown men in their prime to lift Haybags from McCarthy’s public house in Tubberlick to the horse-rail, the back laths of which had been removed so that he could be laid to rest without too much difficulty on the flat of the cart.

Haybags Mullanney weighed twenty-two stone, or as his son Tom might put it, ‘two and threequarter hundred weights of dead weight, deader than the deadest carcass when he has whiskey inside in him.’

‘We’ll have no bother with him,’ Tom announced cheerfully. ‘We’ll take off the back laths first. Then we’ll untackle the horse and heel him out like any other load.’

‘We could leave him in the rail till morning,’ said Jay as soon as he recovered from the convulsions of laughter occasioned by Tom’s suggestion.

‘And suppose,’ said Tom, ‘that he woke up in the middle of the night and found himself on his own, under the stars!’

The trio parted company on this sobering note, Mark turning left into the haggard at the side of the dwellinghouse. The brothers with another half mile to go alighted from the rail, Tom leading the gelding by the head up the steep incline towards the Mullanney homestead, Jay following behind with his hands firmly pressed against the back laths lest Haybags be heeled out before his time.

Nonie Doran stood framed in the doorway as Mark entered the haggard. She watched as he led the mare to the stable. Behind her back her hands clutched an oats’ satchel.

‘Welcome home,’ she called as she approached with the oats.

‘It’s good to be home Ma,’ Mark replied, bending to kiss her gently on the forehead.

‘Every horse earns its oats,’ she laughed as she hung the satchel over the mare’s head. ‘Your own is on the table. I’ll be in shortly.’

Later as he sat replete by the open fire she questioned him about his activities throughout the day. Prices were her paramount interest and then with womanly curiosity she asked about the public houses of Tubberlick and the sayings and doings of the denizens therein. He answered freely. He did not tell her of the idea. She would be the first to know when he started to put it into action. That was her unquestioned entitlement. Theirs was a household which generated a good deal of understandable envy among the hill people. The farm was medium sized, relatively dry and thriving. His father had left no debts. From a purely commercial point of view his demise turned out to be an outstanding asset. Nonie Doran, in order to avail of the widow’s pension, signed the farm, lock, stock and barrel over to her only son, thereby providing them both with a new found independence which could only succeed in enhancing their relationship. Add to this Nonie’s known expertise with all kinds of fowl-rearing, egg-producing, butter-making and calf-rearing, among numerous other attributes and you were left with a model undertaking. The grief which they both felt for the man who had passed on would never really wane but time had brought surcease of the more acute grief.

That night in bed Mark allowed his thoughts to wander to a girl with red hair he had seen in the grocery section of McCarthy’s pub in Tubberlick upon his arrival at the village that very morning. He had nodded warmly but courteously in her direction and she had rewarded him with a smile. From the red head his thoughts wandered to the older of the Mullanney girls Ellie and Bridgie. He made no attempt to dispel their buxom figures from his passionate flights of fancy but it was with the dark eyes of young Annie that his night’s sleep had to contend. Suddenly he blushed and sat upright recalling an incident from the previous year’s corn-threshing in the Mullanney haggard. Without knowing how or why he found himself entangled with her on a deep pile of the loose straw which lay everywhere. His head had been turned somewhat by the two large glasses of whiskey Tom and Jay had handed to him in turn not long before the outrage and that was what he self-righteously called it in the dark of his room.

Suddenly the horseplay stopped and he found himself on his back with Annie kneeling on his chest, her thin hands on his broad shoulders, the sloe-like, wide eyes, infinitely deep, quizzically searching for something he knew not what in his. She had only been fifteen at the time without a breast or a buttock to her as his granduncle’s wife might say.

‘Jesus!’ he cried out panic-stricken, ‘get up girl, won’t your father hang me!’

Frightened and not fully comprehending she stood biting the nails of her right hand her back pressed against an outhouse wall. Rising he brushed the straw from his hair and clothes and then noticing her confusion he called out: ‘Come on. I’ll race you to the house.’

Good God, he thought before he succumbed to sleep, she was only fifteen and me a grown man on top of twenty-six. There had been numerous girls all marriageable but as his granduncle had sagely observed: ‘You’ll be in no hurry. You’ve a mother who’ll look out for you.’

Other mothers with marriageable daughters knew instinctively that Mark was a waste of time, for the present anyway. His mother was a youthful fifty-five and would not be likely to be too favourably disposed towards marriage for her only son. For all their shrewdness and generally unerring instincts they were wrong. Nonie had seen the first grey hair on Mark’s curly black head. She had been twenty-eight herself when she walked up the aisle with Mark’s father and he had been forty. Mark had been a difficult birth, touch and go throughout the delivery and she had been cautioned about further pregnancy. Life was lonely without her husband and the hills were lonely enough especially in winter. A few grandchildren now would change all that.

Two

VESTER MCCARTHY, PROPRIETOR OF McCarthy’s bar and grocery in the village of Tubberlick, stood over six feet two inches in his stockings. He was, if one could place any credence in the claims of his female neighbours in the village’s only street, as fine a figure of a man as ever took leave of a woman’s womb. He carried himself like a field marshal or so he believed and he sported a fine, flowing moustache which lent authority and dignity to an otherwise unengaging face.

In the dance-hall in his younger days it was said of him that he had a beautiful carriage. In truth he had been a past master of the old time waltz in his heyday and it was taken for granted that he would always be the man to lead the floor when the eximious strains of a Strauss waltz or the wilder music of an Irish reel set the feet tapping and the pulses racing. No one ever dared to usurp his position as floor leader in the Tubberlick Parochial Hall or indeed any of the numerous ballrooms, independent and parochial, within a ten mile radius of Tubberlick.

Among other eminent and prestigious distinctions he was chairman of the local football club, secretary of the Tubberlick trout anglers’ association, a leading member of the local confraternity, president of the Parochial Hall Committee and, according to Parson Archibald Reginald Percival Scuttard, Rector of the local Protestant Church, ‘as big a bollix as you’d meet in a three week walk’.

There was only one business in which Vester McCarthy did not involve himself and that was politics. These he eschewed with unflagging diligence although he would always subscribe and be seen to subscribe to church gate collections regardless of the party involved.

‘My conscience will tell me how to vote when the time comes’, he would say whenever he was asked to nominate his choice of candidate.

‘I will always do the right thing on the day’, was another of his favourite retorts and yet there were very few who would consider him evasive. Pillar of the church he might be and moral fibre of the village but he was no paragon. He had two weaknesses if weaknesses they could be called. He indulged in occasional skites and whenever the opportunity presented itself he liked to allow his hand to linger on a well-designed female posterior. His neighbours would say that there was no great harm in a few drinks now and again.

‘And sure,’ they attested with tongue in cheek, ‘the other thing is no more than a sign of health.’

The women of Tubberlick, especially the older women, tended to be more tolerant than the men in this latter respect and were reluctant to condemn those males of the area who might stand accused of excessive interest in the female form and overindulgence, true or false, in impure activities of a sexual nature. To give Vester McCarthy no more than his due he knew which buttocks to pat and he knew where and when to pat them. As in all such perilous exercises, however, it is possible to grievously err on the patability or unpatability of certain buttocks with the direst consequences. Vester McCarthy was no exception. His face had been slapped on occasion. He had been threatened with assault from outraged husbands but because of his size and appearance he was never physically attacked.

‘Such are the hazards of bottom-patting my boy,’ Archie Scuttard was heard to say after it had come to his ears through a crony that Vester McCarthy’s shins had been kicked with more vehemence than was strictly necessary by a new and rather prim, young female teacher who had accepted an appointment in the National School of Tubberlick.

Always after a quarterly fair Vester McCarthy divested himself of his shop clothes and donned one of his better suits preparatory to pub-crawling the village but always ending up, still on his feet, at his own licensed premises.

Sometimes he bought a drink for one of the down-and-outs who regularly propped up the four other bars in the village. It depended on Vester’s mood. If the fair of the day before had brought exceptional business to his bar and grocery he could be depended upon to buy at least one drink for the regular spongers at each of the four pubs.

Occasionally he joined company with the stronger farmers of the hinterland who might have business in the village and stopped off for a drink or two before returning home; other times it might be a fellow publican on an identical peregrination or, to be fair to Vester, anybody or group with a capacity to buy a round of drinks.

After this particular fair, the first quarterly of the year, Vester McCarthy was not in the most jovial of moods. Business had been anything but booming on the previous day and to crown his worries his overall sales had been down since the beginning of the year.

Further compounding his woes was the fact that a number of the smaller, poverty-stricken farmers in the hill country were unable to meet their quarterly obligations and he had been obliged to curtail further credit.

As he entered the Widow Hegarty’s, the last premises before his return to base, who should he happen to see seated unsteadily on a high stool but his archenemy Parson Archibald Reginald Percival Scuttard.

‘Scuttard by name and scuttered by nature.’ He made certain that the phrase was addressed to himself.

‘Nevertheless,’ said he still talking to himself, ‘it wouldn’t do if I didn’t offer the ruffian a drink. I could be accused of religious bias although his likes screwed us into the ground for many a year.’

‘Care for a drink Archie,’ he made the offer as if there never had existed the slightest difference of opinion between them.

‘Sorry old boy,’ Archie Scuttard replied drunkenly, ‘but as you can see I am already in company.’

‘Well if your friend has no objection,’ Vester McCarthy persisted, ‘he’s welcome to one too.’

Archie leaned across the counter and muttered something about gift horses to the Widow Hegarty who took the hint and carefully measured two half-glasses of Jameson seven-year-old into a pewter measure before transferring them to the already partially filled glasses of Archie Scuttard and his friend.

‘You have the advantage over me sir,’ Vester addressed the Parson’s companion knowing that Archie, out of sheer mischief, would never involve himself in such a mundane rite as formal introduction.

‘Oh excuse my ignorance,’ Archie turned around on his stool and with an expansive gesture introduced his friend. ‘Allow me to present my colleague Monsignor…’ Archie’s voice trailed away. He turned to his companion with a quizzical look on his craggy features.

‘Monsignor what was it again old boy?’ he asked.

‘Binge,’ came the reply in a soft American accent. ‘Monsignor Dan Binge.’

Vester McCarthy did well to contain a deep chuckle. Binge and Scuttard he grinned. What a combination and to think that both were clergymen! The thought gave him a feeling of superiority over the Protestant Rector. It was a rare feeling especially since he had always felt inferior in the scoundrel’s company up until then.

‘And how is Mary?’ the Widow Hegarty asked formally.

‘She was often better thank you,’ Vester McCarthy did not refer to his wife’s current ailment. Always in the spring Mary McCarthy was visited by a blight of ugly boils. These occurred for the most part on the posterior where they were safely concealed from the curious eyes of the villages but this springtime her neck had been invaded by a large and ugly swelling which showed no signs of maturing unlike its undercover kindred which disappeared, unfailingly after a fortnight, allowing Vester to re-establish his rightful sovereignty over that part of the anatomy which he held so dear.

‘And Sally?’ the Widow Hegarty asked.

‘Never better,’ Vester lied. The truth was that his only daughter now in her twenty-ninth year was, to put it quite bluntly, starting to feel a real ache for a man. There had been suitors almost from the day she bade farewell to her teens but as in so many similar cases she did not quite fancy what she could have and could not have what she fancied.

***

VESTER AND MARY MCCARTHY had subtly discouraged the less desirable of the suitors and blatantly encouraged others and here we are, thought Vester, at the end of the day back in square one with devil the man to show for all our enterprise. It wasn’t that Sally was too choosy. It was rather that she was unfortunate in that the young men which she fancied were either spoken for beforehand or disinclined to have anything to do with marriage. Only the day before she had suffered another disappointment although she had not felt as disheartened afterwards as she might have. The object of her affection, young Mark Doran, had spent the better part of the afternoon in the bar. She had seen him countless times before on the premises and in the street. Occasionally too he would attend the Sunday night dance at the parochial hall but this time he presented a different image. In the hall he had been in the habit of standing at the rear near the door with the assorted recalcitrants of the parish spotting form as they so vulgarly called it but now he seemed to have assumed a new stature. It was as if he had put that period of wayward youthfulness behind him and come into his own as a man and wouldn’t he be nice too with his own place and a cute, curly head on his fine square shoulders. He wouldn’t be after my money either. It would be Sally’s guess that there was no scarcity in that respect.

‘And I get on well with his mother,’ Sally told herself and this was true for Sunday after ten o’clock Mass Nonie Doran purchased her week’s groceries at McCarthy’s while Mark sampled the wares at the Widow Hegarty’s with his friends from the hill country. Sally had skilfully drawn him into conversation and her mother, fully alerted to the daughter’s strategy, made sure that they were given ample opportunity to converse. Whenever Sally was called upon to dispense an order for drink in Sylvester McCarthy’s Mary McCarthy nimbly stepped in and filled the order herself. Haybags Mullanney in whose company Mark Doran happened to be at the time, had become engaged in conversation with one of the local cattle jobbers. Mark Doran, at least as far as Mary McCarthy could see, seemed interested enough but that night when mother and daughter sat in the kitchen counting the day’s takings it was revealed that Mark seemed only mildly interested. Sally had asked him after an hour’s exclusive conversation if he would be attending the dance on the following Sunday night. He pretended not to hear at first but when she repeated the question he mentioned something about having to visit a granduncle. Only too aware that her chances were running out with every passing year Sally had persevered.

‘I won’t see you there so,’ she said. Again there followed the calculated hesitation.

‘You never know,’ he said which, on reflection, in hill-folk terminology, was as positive an answer as one was likely to get from the young men in that part of the world.

‘Well,’ Sally proposed as she filled a glass of stout for which he had not asked, ‘you’ll surely be there the following Sunday night.’

He shifted on his stool and shook his head in a thoughtful rather than a negative fashion.

‘You’d never know,’ he said.

‘To tell you the truth,’ Sally McCarthy confided, ‘I wouldn’t be bothered going down there now unless I had a date; too many roughs there for my liking. It’s safer to have an escort.’

Mark had nodded agreement and expressed his gratitude when she declined payment for the glass of stout.

‘I’ll tell you what,’ she said, ‘why don’t you call before the dance for a few drinks and we’ll see then.’

‘Well I’d be calling for a few drinks anyway,’ he answered. It had ended at that.

***

‘SALLY MCCARTHY IS A fine and noble cut of a girl,’ Archie Scuttard raised his glass respectfully to his benefactor. ‘As outgoing and sweet a girl as you’d meet in a three week walk.’

The compliment was grudgingly accepted by Vester. For some reason that he could never fathom his daughter was never happier than when in the company of the emaciated Rector who at fifty-five looked every day of three score and ten.

‘He’s certainly not God’s gift to the ladies,’ Vester coldly conveyed his opinion as he preened himself before the large mirror in the haberdashery department which was attached to the grocery which in turn was attached to the pub.

‘No,’ his daughter had answered, ‘but he’s respectful and a gentleman after his fashion.’

‘You call that bawdy, foul-mouthed wretch a gentleman!’ Vester produced a pocket comb and, combing his silvery locks, indented several waves across the dome of his head. Much as she admired and loved him Sally McCarthy was only too painfully aware of her father’s vanity and his sanctimonious reaction to all the things which seemed harmless to his daughter. In her view the Parson was a man with little time for cant or hypocrisy and if his language was coarse at times it was so laced with humour that only the most squeamish could possibly take exception except, when deep in his cups, he availed of his comprehensive repertoire of dirty limericks to scandalise any self-righteous patrons he might encounter in public houses after hours.

‘You’re not a native of these parts Monsignor Binge?’ Vester McCarthy posed the question respectfully more for the purpose of making conversation than out of any idle curiosity.

‘No Vester. Indeed no. I am a Kilkenny man even if my American twang might suggest that I am a native American.’ The Monsignor spoke with a strong Californian accent. He lifted his whiskey glass and like Archie Scuttard conveyed his thanks to the purchaser.

‘Are you on holiday then?’ Vester McCarthy was curious now but no less respectful.

‘I propose to spend a few days in your beautiful countryside Vester, that’s if nobody objects.’

‘Let me be the first to extend a welcome,’ Vester McCarthy drew himself up to his full height as though he was the official spokesman for the entire parish of Tubberlick. He shook the Monsignor’s hand with all the fervour that might be expected from such a dignitary.

‘You have friends here or relations maybe,’ Vester asked.

‘My sister lives here,’ the Monsignor replied, ‘Mrs Tom Heavey at the end of the street.’

‘Ah so you’re Madge Heavey’s brother! I assure you sir that you are now doubly welcome. Madge is a personal friend of mine.’

Vester would have to admit to himself that Madge’s was one of the few posteriors he had not patted or tried to pat. He always got the distinct impression that hers was a posterior not for patting. Several whiskies later Vester was tempted to ask if the clergymen had met by chance of if they had know each other previously.

‘We have never met,’ Archie Scuttard replied, ‘until now and I must confess that I would know very little about him but for your insatiable curiosity McCarthy.’

‘Why thank you Parson,’ came the amicable reply. It transpired as the night wore on and the witching hour put safely behind them that the Rector and the Monsignor had much in common. Both had been chaplains in France towards the end of the Great War. Both had been wounded, the Rector in the Battle of the Somme as a result of which he had been decorated for gallantry.

***

THE FACT THAT HE was the owner of the much-coveted Victoria Cross might never have emerged had not an item appeared in a gazette which a Tubberlick matron had picked up by chance while awaiting her turn in a ladies’ hairdressing salon in Killarney. Like any self-respecting product of her native place, worried abut that place’s reputation abroad, she transferred the magazine to her handbag when nobody was looking. Her duty done by her village and by her religion which was, of course, Catholic she decided to forego the luxury of the set and wash which she had planned and repaired instead to the lounge of the Great Southern Hotel where she might digest in peace the latest transgression by the Tubberlick Rector. Imagine her disappointment when she discovered that the piece had to do with the number of Trinity College graduates who had been decorated during the 1914–1918 war. Archibald Reginald Percival Scuttard figured in the list as did the hitherto undisclosed fact that he had graduated with honours in classics from Trinity and also had the letters Oxon after his name. The Oxon meant little to the farmers of the Tubberlick hill country but the Victoria Cross did. Bravery was bravery no matter which side a man took in any conflict. The disclosure endeared him even further to hill people although he didn’t have a single parishioner among them.

The twenty Protestant families in the united parishes of Tubberlick, Tubberlee, Ballybo, Kilshunnig and Boherlahan, occupied the valleys and lower slopes of the so-called parishes in question.

‘How is it you’ll never see a Protestant with bad land?’ Mark Doran had once put the question to his father.

‘Because they made sure they picked the best of it when the Catholics weren’t allowed title,’ his father tried to explain.

The Protestant families still survived after hundreds of years. Their numbers had been in serious decline since the War of Independence and many had sold out through fear but there was no intimidation as long as they stayed in the middle of the road throughout the Troubles.

The Tubberlick Protestant community was the last surviving one between the hill village and the town of Trallock thirty miles away while not a single Protestant remained in the vast and mostly fertile countryside between Tubberlick and Killarney. Their decline was to be mourned, all fair-minded Catholics in the five depopulated parishes would agree. They were a thrifty and industrious people, good neighbours and dependable in any emergency. A minority intermarried with local Catholics but nearly always there was trouble when it came to deciding the religion of the children. Tubberlick had experienced its own boycott of a Protestant farmer when he failed to honour a dubious premarital promise that the children of the union would be baptised into the Catholic faith. The boycott was vicious and relentless. Many thought it inhuman. The persecuted family sold out and settled in the midlands where many of their own kind still farmed. At the time the hill people disapproved but made no protest such was the influence of the local Catholic clergy backed by their bishop and the more zealous of the villagers. Then there were the young men and women of the district who were easily influenced at the time. Roads were painted with anti-Protestant slogans and, generally speaking, the victim of the boycott was treated like a Pariah. For all his household wants he was obliged to make the long journey to Killarney or Trallock.

The village’s sole hackney car was not available to him at any price. Most of those involved would now like to forget the roles they had played, especially the younger people who later saw themselves as dupes. Throughout the entire episode the Rector of Tubberlick had denounced the boycott declaring to anybody who would listen that he didn’t care whether the child was brought up Catholic, Protestant or Mohammedan as long as the victimisation ended.

By tacit agreement there was never mention of what happened in the public and business houses of the village thereafter. It would remain a distant cloud however.

***

TOWARDS THE END OF the drinking session at two-thirty in the morning an argument broke out between the Rector and Vester McCarthy. Commenting on the decline in the cattle numbers at the quarterly fair the Rector suggested it could well have occurred because of collusion between cattle jobbers. It was rumoured, discreetly as one would expect, that Vester McCarthy was secretly financing at least one of the five jobbers who usually attended the Tubberlick quarterlies. The gentleman in question was a member of a local family of drovers who had a monopoly on all the droving activities of the several villages within the hill country. The Rector didn’t have hard proof but the members of the family in question confined all of their drinking to the McCarthy premises and it was well known that they couldn’t muster the price of a single Roscrea between the lot of them. Where then did the money come from! The jobber was the father figure of the family which included married sons, daughters and several ne’er do well sons-in-law who seemed not to have the capacity for any form of honest toil other than occasional droving unless one took into account their efficacy in keeping their wives pregnant year in, year out.

‘It has come to my attention,’ Vester McCarthy’s voice rose angrily as he turned on the Rector, ‘that you have been advising your flock to withhold their cattle from the Tubberlick fairs. I find this very surprising for a man who lives and works in Tubberlick and who should know better than any that charity begins at home.’

‘Charity for whom,’ the Rector asked, ‘for the jobbers and their puppet master is it?’

Incensed by the reference to his suspected connections with the cattle jobbers Vester drew back his hand to strike at his tormentor but Monsignor Binge succeeded in holding him at bay.

‘There’s witnesses here,’ Vester McCarthy shouted, ‘and if you make any more accusations against me you’ll answer in a court of law.’

‘All I’m trying to say,’ the Rector was calm now, ‘is that the local cattle jobbers have frightened away many of the farmers.’

‘The bloody Protestant farmers only,’ Vester shouted back, ‘and all primed by you. Your sole aim seems to be the destruction of the business life of the village.’

‘Nonsense,’ the Rector returned. ‘It is the jobbers who are doing that and this should be known to you better than anybody.’

‘Is it not true,’ Vester was at his most accusatory now, ‘that Daisy Popple withdrew her ten store bullocks on your advice even when she had been offered more than she might get at any other fair in the district?’

‘Not more and considerably less than she might get in Trallock or Killarney,’ the Rector corrected.

‘And how the hell,’ Vester roared, ‘is she going to get them to Trallock or Killarney, on her bloody back is it!’

‘Looks like the only way all right with not a drover willing to drive them and I wonder who instructed them? It wasn’t off their own bats Mr McCarthy so it had to be someone else. I’ll mention no names but that somebody else is an overbearing oul’ bollix with waves in his hair and a moustache under his nose.’

Enraged, Vester McCarthy sought to strangle the Rector. The Monsignor, aided by the Widow Hegarty and two other drunken revellers, succeeded in restraining the apoplectic publican, now taunted beyond endurance.

‘If there’s another word,’ the Widow cautioned, ‘I’ll clear the house.’

‘Maybe,’ Monsignor Binge suggested, ‘it might be a good idea to clear it anyway. My sister will be wondering.’

‘Your sister knows you’re in good hands Monsignor,’ the Widow assured him. There were to be no further exchanges between the Rector and Vester McCarthy on that occasion but word of the ruction would spread far and wide in a matter of weeks, with the hill people coming down firmly on the side of the Rector and the majority of the village backing Vester McCarthy.

As they left the pub not long after the Monsignor’s prompting, a cold wind blew up the village street. On his way out Vester had allowed his hand to linger on the ample buttocks of the Widow as she looked up and down the street to make sure no tale-carrier was in the vicinity. If she felt anything; revulsion, shock, joy or elation, it did not register on her face or movements. It would be true to say that it was a backside that had been handled and fondled tenderly, indifferently and savagely down the years and, therefore, it would be fair to assume that she took such liberties in her stride. It would be also true to say that no man had ever been admitted to her private quarters after hours. This sanctum sanctorum, which was isolated from the public premises by a locked door at all times, contained a small kitchen, a bedroom and a sitting-room where she would sit and drink tea after the last of the customers had departed. Not only did she never entertain male visitors but she never entertained even a thought of male visitors. She had been a widow for twenty years and she would remain a widow until the end of her days and in case doubt ever arose about her position in this respect she would make an announcement from time to time, especially in the presence of her more amorous regulars, that any sort of intimate relationship with a man was the last thought in her head.

‘Can I drop you off?’ the invitation came from the Rector as he mounted a large, ungainly-looking motor bike which had been parked, for most of the night and early morning, outside the Widow’s door. Monsignor Binge was at first tempted to decline the offer but he reassured himself with the belief that little harm could befall him during a journey which was no more than two hundred yards. He was about to mount the pillion when a mellifluous male voice advised him against it. The proprietor of the pleasant tones was a large, chubby member of the civic guards who had materialised, magically as if from nowhere.

‘You go on home now,’ the voice was saying, ‘and don’t worry about the bike Archie. I’ll look after it.’

Blearily Archie Scuttard identified the newcomer to the deserted street.

‘Ah ’tis you Mick,’ he said agreeably, ‘allow me to introduce my friend.’

‘We’ve already met,’ Mick Malone informed the Rector as he helped him from the bike to the roadway.

***