0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Book House Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

This book contains several HTML tables of contents.The first table of contents (at the very beginning of the ebook) lists the titles of all novels included in this volume. By clicking on one of those titles you will be redirected to the beginning of that work, where you'll find a new TOC that lists all the chapters and sub-chapters of that specific work.Here you will find the complete Edgar Allan Poe’s tales and poems —over 135 works— in the chronological order of their original publication.The Tales:A Tale of JerusalemBon-Bon Loss of Breath MetzengersteinThe Duc de l’OmeletteMS. Found in a BottleThe Assignation BereniceKing PestLionizingMorellaShadow The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans PfaallFour Beasts in One Mystification The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of NantucketHow to Write a Blackwood Article A PredicamentLigeiaSilence — A Fable The Conversation of Eiros and CharmionThe Devil in the BelfryThe Fall of the House of UsherThe Man that was Used UpWhy the Little Frenchman Wears His Hand in a SlingWilliam WilsonThe Business Man The Journal of Julius RodmanThe Man of the CrowdA Descent into the MaelströmEleonoraNever Bet the Devil Your HeadThe Colloquy of Monos and UnaThe Island of the FayThe Murders in the Rue MorgueThree Sundays in a Week The Domain of Arnheim The Masque of the Red DeathThe Mystery of Marie RogetThe Oval Portrait The Pit and the PendulumRaising the Wind The Black CatThe Gold-BugThe Tell-Tale HeartA Tale of the Ragged MountainsMesmeric RevelationThe Angel of the OddThe Balloon HoaxThe Literary Life of Thingum Bob, Esq.The Oblong BoxThe Premature BurialThe Purloined LetterThe SpectaclesThou Art the ManThe Facts in the Case of M. ValdemarThe Imp of the PerverseThe Power of WordsThe System of Dr. Tarr and Prof. FetherThe Thousand-and-Second Tale of ScheherazadeSome Words with a MummyThe Cask of AmontilladoThe SphinxHop-Frog or the Eight Chained Ourang-OutangsLandor’s CottageMellonta TautaThe Light-HouseVon Kempelen and His DiscoveryX-ing a ParagrabAnd all the Poems.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

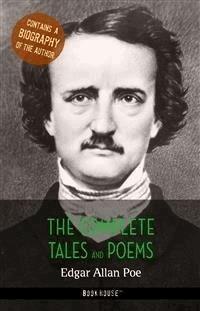

Edgar Allan Poe

THE COMPLETE TALES AND POEMS

2017 © Book House Publishing

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic,

mechanical, photocopying,

recording or otherwise,

without prior permission of

Book House.

Get your next Book House Publishing title for Kindle here

Table of Contents

Edgar Allan Poe — An Extensive Biography

The Tales

The Poems

Edgar Allan Poe — An Extensive Biography

by Eugene LeMoine Didier

Chapter 1 — Memoir of Edgar A. Poe

Chapter 2 — The Poe Cult

Chapter 3 — Poe: Real and Reputed

Chapter 4 — The Boyhood of Edgar A. Poe

Chapter 5 — Poe’s Female Friends

Chapter 6 — Poe and Mrs. Whitman

Chapter 7 — The Loves of Edgar A. Poe

Chapter 8 — Poe and Stoddard

Chapter 9 — Ingram’s Life of Poe

Chapter 10 — Woodberry’s Life of Poe

Chapter 11 — Recent Biographies of Edgar A. Poe

Chapter 12 — The True Story of Poe’s Death

Chapter 13 — The Grave of Poe

Chapter 14 — The Poe Monument

Chapter 15 — Portraits of Poe

Chapter 16 — The Poe Mania

Chapter 17 — The Semi-Centennial of America’s Famous Poet

Chapter 18 — The Truth About Edgar A. Poe

Chapter 19 — Edgar Allan Poe in Society

Chapter 20 — Recollections of Edgar A. Poe

Chapter 21 — Poe as Seen by Stoddard, Stedman, and Harrison

Chapter 22 — The “Discoverer” of Poe

Chapter 23 — Poe and the University of Virginia

Chapter 24 — The Centennial of the Birth of Edgar A. Poe

Chapter 1 — Memoir of Edgar A. Poe

The year of Edgar A. Poe’s birth — 1809 — was an annus mirabilis in literary history. In that year were born Alfred Tennyson, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Edward Fitzgerald, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Charles Darwin, William E. Gladstone, besides the subject of this Memoir. Among these illustrious names, Edgar A. Poe was the first in point of time, and, in the estimation of many, the first in genius. For three score years and more the time and place of his birth were unknown. His early biographers gave 1811 as the time, and Baltimore as the place of his birth. In order to ascertain the truth about the matter, I consulted Mrs. Maria Clemm, the poet’s aunt and mother-in-law, who told me that he was born in Boston, on the 19th of January, 1809.

Although more than a dozen lives of Poe have been written, there is an amazing amount of ignorance upon the subject. This ignorance is not confined to the “average reader,” but I have known college professors — professors of English in reputable colleges — so grossly ignorant of the facts of Poe’s life that they did not know when and where some of his most remarkable tales were written; and who accepted with childish credulity the malicious and mendacious stories told of him by his enemies.

David Poe, Junior, the father of the poet, was the eldest son of General David Poe, of Baltimore. As the younger Poe grew to manhood, he displayed a fondness for amateur acting, and, with some other youths, formed a Thespian Club which met in an attic room of his father’s house. David Poe was a law student, but so great was his passion for the stage, that, in 1804, he threw aside his law books, and joined a troup of strolling players. C. D. Hopkins, the light comedian of the company, died in 1805, and, in a few months, Poe married his widow, whose maiden name was Elizabeth Arnold. She was of English birth — pretty, clever, sprightly, vivacious, and a great favorite on the stage. After their marriage they continued their wandering theatrical life, traveling up and down the Atlantic Coast from Boston to Charleston. When they died — Mrs. Poe on December 8, 1811, in Richmond, her husband, in Norfolk, a few weeks previously — they left three helpless children — the eldest, William Henry Leonard, was adopted by his grandfather, General Poe; Edgar was adopted by Mr. and Mrs. John Allan, of Richmond, and Rosalie, by Mr. and Mrs. Mackenzie, of the same city. The future poet was early taught to read, write, draw, and recite verses. On the 17th of June, 1815, Mr. and Mrs. Allan sailed for London, taken their adopted son with them. They remained abroad five years, during which time Edgar was a pupil of Dr. Bransby’s Manor House School, at Stoke-Newington, near London. This school and its surroundings made a lasting impression upon the receptive mind of the young student, and he described it with minute accuracy in “William Wilson,” one of his most striking and original tales.

When the Allans returned to Richmond, in 1820, Edgar became successively a pupil of the schools of Joseph H. Clarke and William Burke. He stood high in all his classes, and was a great favorite of his teachers and fellow students. Professor Clarke told me that Edgar wrote genuine poetry even in those early days; he was a born poet; his poetical compositions were universally admitted to be the best in the school, while the other boys wrote mere mechanical verses. As a scholar, he was ambitious and always acquitted himself well in his studies. During the three years he was at Professor Clarke’s school, he read the principal Latin and Greek authors; but he had no love for mathematics. He had a sensitive and tender heart, and would do anything to serve a friend. His nature was entirely free from selfishness, the predominant defect of boyhood. At the end of the scholastic year, in the summer of 1823, Professor Clarke removed from Richmond, upon which occasion Poe addressed a poetical tribute to him.

William Burke took Professor Clarke’s school and most of his pupils; among them Edgar Poe. Several years ago Andrew Johnston, of Richmond, furnished me with the following particulars:

“I entered Mr. Burke’s school on the first of October, 1823, and found Edgar A. Poe already there. I knew him before, but not well, there being two, if not three, years difference in our ages. He attended the school all through 1824, and part of 1825. Some time in the latter year he left. He was a much more advanced scholar than any of us; but there was no other class for him — that being the highest — and he had nothing to do, or but little, to keep at the head of the school. I dare say he liked it very well, for he was fond of general reading, and even then he wrote verses very clever for a boy of his age, and sometimes satirical. We all recognized and admired his great and varied talents, and were proud of him as the most distinguished schoolboy in Richmond.

“At that time Poe was slight in person, but well-made, active, sinewy, and graceful. In athletic exercises he was foremost: especially, he was the best, the most daring, and most enduring swimmer that I ever saw in the water. When about sixteen years old, he performed his well-known feat of swimming from Richmond to Warwick, a distance of five or six miles. He was accompanied by two boats, and it took him several hours to accomplish the task, the tide changing during the time.

“Poe was always neat in his dress, but not foppish. His disposition was amiable, and his manners pleasant and courteous.’’

After leaving Burke’s school in March, 1825, Mr. Allan placed Edgar under the best private tutors in order to prepare him for the University of Virginia. He devoted himself to the classics, modern languages, and belles-lettres. Richmond at that time, as now, was celebrated for its polished society. Into this society Edgar Poe was early welcome — a boy in years, but a man in mind and manners. The refined grace and courtesy toward women that ever distinguished him may have been then acquired in the best society of Virginia’s beautiful capital.

On the 14th of February, 1826, Poe entered the University of Virginia. The studies which he selected were ancient and modern languages, and he attended lectures in Latin, Greek, French, Spanish, and Italian. He read and wrote Latin and French with ease and accurately, and, at the close of the session, was mentioned as excellent in those languages. His literary tastes were marked while at the University, and among the professors he was regarded as well behaved and studious. At the end of the session, December 15, 1826, he graduated in Latin and French, and returned to Richmond. Soon after his return, Mr. Allan placed him in his counting room, but the future poet could not brook the dull life of a clerk, and, in a few weeks, took French leave. Now commenced that restless, wandering life which continued until the end. In the Spring of 1827, he found himself in Boston, his native city, where his mother had made many friends before his birth. Here the first edition of his “Tamerlane and Other Poems,” was printed — forty copies. This tiny volume of less than forty pages has become one of the rarest books in the world, only three or four copies are known to be in existence, and has sold as high as $2,550.

Having no money, and no prospect of making any, on May 26, 1827, he enlisted as a private soldier in the United States Army, under the name of Edgar A. Perry, and was assigned to Battery H of the 1st artillery. After a short service in Boston his battery was ordered to Fort Moultrie, near Charleston, S. C. It was while stationed there that the story of a buried treasure was suggested to him, which was afterward made the subject of one of his most remarkable tales — “The Gold Bug.” By 1829 he was at Fortress Monroe, his good conduct and strict attention to his duties having earned his promotion to the rank of sergeant-major. The officers under whom he served soon discovered that he was far superior in education to his position, and he was employed as company clerk and assistant in the Commissary Department. The discovery of Poe’s army record, taken from the Records of the War Department at Washington, disproves at once and forever the romantic story that he went to Europe after leaving the University of Virginia for the purpose of engaging in the struggle for Grecian independence, to which the death of Byron had attracted the attention of the world.

On February 28, 1829, his kind, indulgent mother, by adoption, Mrs. Allan, died. Her death was a great misfortune to Poe, as she had always stood between him and her stern, relentless husband. On April 15, 1829, having secured a substitute, our sergeant-major was honorably discharged from the army, and paid a visit to Baltimore, probably in order to look up his relatives there. His second book, “AlAaraaf, Tamerlane, and Minor Poems,” was published in Baltimore in 1829 — a thin volume of seventy-one pages. A copy of this edition, enriched with notes by the author, has advanced in price from $75, in 1892, to $1,825, in 1903.

Mr. Allan, wishing to place his wayward ward where he could earn a living, and, at the same time, be free from all future responsibility, obtained his appointment to West Point. He entered the academy on July 1, 1830, perhaps the most brilliant and gifted cadet that ever went there. He was in the flower of youth, and in the first bloom of that remarkable beauty of face and form which distinguished him through life. His rich, dark hair fell in abundant clusters over his high, white, magnificent forehead, beneath which shone the most beautiful, the most expressive of mortal eyes. He was of medium height, but elegantly formed, his bearing being proud, lofty, and fearless.

Poe stood high in his classes, especially in French and mathematics — his great fault was his neglect of, and apparent contempt for, his military duties: His capricious temper made him, at times, utterly oblivious or indifferent to the ordinary routine of roll-calls, drills, and guard duty. These were all and each utterly distasteful to the young poet, whose soul was filled with a burning ambition. He turned with delight from military tactics to the classic pages of Virgil; he neglected mathematics for the fascinating essays of Macaulay, which were just then beginning to charm the world; he escaped from the evening parade to wander along the beautiful banks of the Hudson, meditating his tuneful “Israfel,” and, perhaps, planning “Ligeia,” or, “The Fall of the House of Usher.”

These irregular habits subjected the cadet to frequent arrests and punishments, and effectually prevented his learning to discharge the duties of a soldier. Before Poe had been at West Point six months, he found the rigid discipline so intolerable that he asked permission of Mr. Allan to resign. This was peremptorily refused. The reason was obvious: within a year after the death of his first wife, Mr. Allan married Louise Gabrielle Patterson, of New Jersey, and, a son being born, Edgar Poe was no longer the heir to his princely fortune, and he wished to keep his ward in an honorable profession which would give him a support for life. Hence he refused to allow him to leave West Point — consent of father or guardian being required before a cadet could resign. But Poe was determined to get away from the academy, with or without Mr. Allan’s consent. So he commenced a regular and deliberate neglect of duties and disobedience of rules: he cut his classes, shirked the drill, and refused to do guard duty. The desired result followed: on January 7th, 1831, cadet Edgar A. Poe was brought before a general court-marshal, charged with “gross neglect of all duty, and disobedience of orders.” The accused promptly pleaded “guilty” to all the specifications, and, to his great delight, was sentenced “to be dismissed from the service of the United States.”

About the time that Poe was dismissed from West Point, he published a third volume, entitled “Poems, by Edgar A. Poe.” The volume contained “Al Aaraef,” and “Tamerlane,” from the edition of 1829, omitting all the others, but adding the exquisite lines “To Helen,” which has won the admiration of all readers; the tuneful “Israfel,” “Irene” (afterward remodeled into “The Sleeper”), and four smaller poems. The book was dedicated to the United States Corps of Cadets, an honor which the cadets did not deserve, for they declared the verses “ridiculous doggerel.”

When Poe was dismissed from West Point, he was in the situation of Adam when he was expelled from the Garden of Eden — the world was all before where to choose. He was homeless, penniless, friendless. He had been taught to spend thousands, but had never been taught to earn a dollar. In this emergency he made his way to Richmond, and presented himself at the home of his youth — the only home he had ever known — the Allan mansion on the corner of Fifth and Main Streets. His reception was not that of the Prodigal Son when he returned to his father’s house: no fatted calf was killed — no friends were invited to meet him — no feast was spread to welcome the wanderer home. He was coldly received, where he had once been the idolized child of the house. We all know the influence of a young wife upon a fond, doting old husband. The second Mrs. Allan looked with disfavor upon Poe’s presence in the house, and when he appeared, he was told that his former room, which was always kept ready for him by the first Mrs. Allan, was now a guest chamber, and he was assigned to a small room at the back of the house, which had been occupied by Mrs. Allan’s maid. The proud and high-spirited young man keenly felt this indignity, and, refusing to allow his satchel to be carried to the room, determined to see Mrs. Allan. A stormy interview followed, and Poe left the house forever. A letter written to me by a Richmond lady, who claimed to be “a confident of Mr. Poe’s,” says the cause of the quarrel between Poe and Allan “was very simple and very natural under the circumstances, and completely exonerates Poe from ingratitude to his adopted father.” Whatever was the cause, the result was that Poe left the house as already mentioned. Writing many years afterward to one who possessed his entire confidence, Mrs. Sarah Helen Whitman, he used this passionate language:

“By the God who reigns in heaven, I swear to you that I am incapable of dishonor. I can call to mind no act of my life which would bring a blush to my cheek or to yours. If I have erred at all, in this regard, it has been on the side of what the world would call a Quixotic sense of the honorable — of the chivalrous. The indulgence of this sense has been the true voluptuousness of my life. It was for this species of luxury that in early youth I deliberately threw away from me a large fortune, rather than endure a trivial wrong.”

After the affair with Mrs. Allan, just mentioned, Poe probably went to Baltimore, and resided with his aunt, Mrs. Maria Clemm. For the next two years all trace of him is lost, excepting a letter which he wrote on May 6th, 1831, in which he asked William Gwynn, a Baltimore editor, for employment in his office. Not meeting with any encouragement, he next applied to Dr. N. C. Brooks for a position in the school which he had recently established at Riestertown, in Baltimore County. Fifty-eight years afterward, Dr. Brooks told me of this, and said he regretted at the time there was no vacancy, as he knew that Poe was an accomplished scholar.

During those two years Poe was not idle, for, when the Baltimore Saturday Visitor, in the summer of 1833, offered one hundred dollars for the best prose story, and fifty dollars for the best poem, he submitted his “Tales of the Folio Club,” comprising “A Manuscript Found in a Bottle,” “A Descent into the Maelstrom,” “Adventures of Hans Pfaall,” “Berenice,” “Lionizing,” “A Tale of the Ragged Mountain,” etc. He also sent in for competition a poem, “The Coliseum.” Both prizes were awarded to Poe by the committee, but, as it was not deemed expedient by the proprietor of the Saturday Visitor to bestow both prizes upon the same person, he was awarded the hundred-dollar prize for “A Manuscript Found in a Bottle,” and an unknown local genius was given the fifty dollars for the best poem, which was no poem at all.

The hundred-dollar prize was the first money that Poe ever received from literary work, and, from that time until his death, he never earned a dollar except by his pen. He was at that time twenty-four years old, unconscious that there was before him sixteen years of suffering and sorrow, of heroic struggle, of splendid achievement, and immortal fame!

In winning the hundred-dollar prize, Poe won, at the same time, a good and true friend in John P. Kennedy, who was one of the three gentlemen who composed the committee of award. Every admirer of Poe should appreciate Mr. Kennedy’s kindness to the young poet. He alone, of the committee, extended a helping hand to the unknown but ambitious young author. He invited him to his house, made him welcome at his table, and furnished him with a saddle horse, that he might take exercise whenever he pleased. He did more: he introduced him to Thomas W. White, proprietor of the Southern Literary Messenger, then recently started in Richmond, and recommended him as being “very clever with his pen, classical, and scholar-like.” Mr. White invited Poe to send him a contribution, and, in the March number, 1835, his strangely beautiful tale, “Berenice,” was published in the Messenger, and attracted immediate attention. From that time, for two years, Poe was a regular contributor to that magazine, and was rapidly making his name and that of the Messenger known through the country.

Malice and ignorance have caused Poe to be charged with pride and ingratitude. That these vices were foreign to his nature, we have abundant evidence, all through his life. Here are two examples which occurred at the period about which we are now writing: He visited each of the gentlemen who awarded him the prize, and thanked them for their approval of his literary work. Again, in order to show Poe’s gratitude to Mr. Kennedy, I quote two passages from a letter written to Mr. White, dated Baltimore, May 30, 1835. He had written a criticism of Kennedy’s once famous historical novel, “Horse-Shoe Robinson,” and apologizing for the hasty sketch he sent, instead of the thorough review which he intended, says, “At the time I was so ill as to be hardly able to see the paper on which I wrote, and I finished it in a state of complete exhaustion. I have not, therefore, done anything like justice to the book, and I am vexed about the matter, for Mr. Kennedy proved himself a true friend to me in every respect, and I am sincerely grateful to him for many acts of generosity and attention” In that same letter, in answer to Mr. White’s query, whether he was satisfied with the pay he was receiving for his work on the Messenger, Poe wrote: “I reply that I am, entirely. My poor services are not worth what you give me for them”

For two or three years, Edgar Poe had been engaged in the most delightful of occupations — the instruction of a young girl, singularly beautiful, interesting, and truly loved. For two or three years Virginia — his starry-eyed young cousin — had been his pupil. Never had teacher so lovely a pupil, never a pupil so tender a teacher. They were both young; she was a child

But our love it was stronger by far than the love

Of those who were older than we.

Under the name of Eleonora, Edgar tells the story of their love: “The loveliness of Eleonora was that of the seraphim, and she was a maiden artless and innocent as the brief life she had led among the flowers — I, and my cousin, and her mother”

Mr. White soon saw how valuable to his magazine were the contributions of Edgar Poe, and in the summer of 1835 he offered him the position of assistant editor of the Messenger, at a salary of ten dollars a week. He gladly accepted this offer, and prepared to remove to Richmond immediately, and his letters show that, on the 20th of August, 1835, he was in that city.

In spite of his rising fortune and increasing fame, he felt most keenly the separation from “her he loved so dearly.” For years Virginia had been his daily companion and confidante. Like Abelard and Heloise, they had but one home and one heart. In the first days of this separation he wrote his friend, Mr. Kennedy, a letter, dated Richmond, September 11, 1835, in which, after expressing a deep sense of his gratitude for his frequent kindness and assistance, he says: “I am suffering under a depression of spirits such as I never felt before. I have struggled in vain against the influence of this melancholy; you will believe me when I say that I am still miserable, in spite of the great improvement in my circumstances. Write me immediately; convince me that it is worth one’s while — that it is at all necessary — to live, and you will prove indeed my friend. Persuade me to do what is right. I do, indeed, mean this. Write me, then, and quickly. Your words will have more weight with me than the words of others, for you were my friend when no one else was.”

So great satisfaction did Poe give by his work as assistant editor of the Messenger, that, in December, 1835, White made him the editor of the magazine, and increased his salary to $800 a year.

As his pecuniary prospects brightened, his first thought was to bring his aunt and cousin to Richmond, where, in May, 1836, Edgar and Virginia were married.

During the nineteen months that Poe was with the Messenger, the circulation of the magazine increased from 700 to 5,000. This remarkable increase of circulation was chiefly due to Poe’s brilliant contributions, which attracted the attention of the whole country. Between December, 1835, and September, 1836, he wrote ninety-four reviews, more or less elaborate, but all striking. Even at that early period of his literary life, he showed that artistic finish of style which distinguished his whole career, and that power of analysis and abhorrence of careless writing which was always one of his marked characteristics. These early critiques were not by any means condemnatory. In fact, only three of the whole ninety-four were decidedly harsh. No American critic had a more sincere appreciation of literary excellence than Poe, and he showed it in his criticism. George Parsons Lathrop, whose worship of Hawthorne was inspired by his love of Hawthorne’s lovely daughter, Rose, was unjust and unappreciative of Poe, but he was forced to admit that, “we owe to Poe the first agile and determined movement of criticism in this country, and, although it was a startling dexterity which winged his censorial shafts, he was excellently fitted for the critic’s office in one way, because he knew positively of what standards he meant to judge by, and kept up an inflexible hostility to any offense against them. He had an acute instinct in matters of literary form; it amounted, indeed, to a passion, as all his instincts and perceptions did; he had, also, the knack of finding reasons for his opinions, and of stating them well. All this is essential to the equipment of the critic.”

An estimate of Poe as a poet by the same unfriendly critic is worth preserving: “As a mere potency, Poe must be rated almost highest among American poets; and high among prosaists; no one else offers so much pungency, such impetuous and frightful energy crowded into such small space... Let us call Poe a positive genius. He would have flourished anywhere in much the same way as he did in America.”

Hawthorne said: “I do not want to be a doctor and live by men’s diseases, nor a minister and live by their sins, nor a lawyer and live by their quarrels. So, I do not know that there is anything for me but to be an author.” His relatives urged him to go into business, his genius forbade it. He was made to feel that he was a useless dreamer, and this drove him in upon himself; but he persisted. Poe must have felt the same way, saying, “I do not want to be a soldier and kill men, and I won’t; I will be an author;’’ and he was. Hawthorne was the natural result of the grim, gloomy, stern Puritan spirit, but Poe had no literary ancestors: he stands alone as a strange, unique, mysterious, fascinating figure in the literature of the world, representing no country, no race, no time. His genius was alien to American soil. He stands alone among American poets as Shakespeare stands alone among the poets of the world. He had no predecessor; he has had no successors. His appearance in the literary world was as sudden and unexpected as it was strange and wonderful. His original and distinct genius astonished the world like a new, brilliant planet suddenly appearing in the heavens.

Poe’s message to the world was that man does not live by bread alone — that there is a higher, nobler, grander ideal to be realized than money-getting, commercialism, materialism. Poe’s genius was a revelation to the world — his extraordinary gifts elevated him far above all his contemporaries, and placed him as a star, apart. His own countrymen were not ready to receive him when he came, and he suffered accordingly. One poet like Poe is worth more to the world than a hundred Rockefellers, Vanderbilts, Goulds, Carnegies, and Harrimans. Such men are the natural product of American life, but Almighty God alone can produce a poet of inspired genius. Poe had the culture that sometimes is lacking in genius; he had the refinement which is sometimes wanting in great minds. It is not the millionaire, but the poet that makes life worth living. The millionaire is really a blot upon American civilization; the poet gives life a tone and a color. It has been said that the memories of kings and conquerors flit like troubled ghosts through the pages of history; but it is only the name of the thinker of great thoughts, the poet of rare gifts that foreign nations and after generations cherish. Like Bacon, Poe might have left his “name to the next ages and to foreign nations.” For his fame has grown steadily since his tragical death, not only in his own land, but among “foreign nations.”

It should be mentioned that Poe was only twenty-six years old when he was made editor of the Southern Literary Messenger, and that, in less than two years, he gave it a commanding position among American magazines. Perhaps no similar enterprise ever prospered so largely in its commencement, and none in the same length of time — not even Blackwood, in the brilliant days of Maginn, ever published so many dazzling articles from the same pen. Strange stories of the German school, akin to the most fanciful legends of the Rhine, fascinating and astonishing the reader with the verisimilitude of their improbability, appeared in the same number with lyrics plaintive and wondrous sweet, the earliest vibrations of those chords which have since sounded through the world.

In January, 1837, the blood of the wanderer, which he derived from his actress-mother, drove him from Richmond to New York, in which city Mrs. Clemm started a boarding house on Carmine Street. One of the few boarders was William Gowans, the eminent second-hand bookseller, who has left an interesting account of Poe at that time: “For eight months or more ‘one house contained us, as one table fed.’ During that time I saw much of Edgar A. Poe, and had an opportunity of conversing with him often, and, I must say that, I never saw him the least affected with liquor, nor even descend to any vice, while he was one of the most courteous, gentlemanly, and intelligent companions I have met with during my journeyings and haltings through divers divisions of the globe; beside, he had an extra inducement to be a good man as well as a good husband, for he had a wife of matchless beauty and loveliness; her eye could match that of any houri, and her face defy the genius of a Canova to imitate; a temper and a disposition of surpassing sweetness; besides, she seemed as much devoted to him and his every interest as a young mother to her first-born. Poe had a remarkably pleasing and prepossessing countenance, what the ladies would call decidedly handsome.”

Poe’s object in removing to New York, at this time, was because he thought that city offered greater advantages to a professional man of letters than the provincial town of Richmond. He was promised a position on the New York Review, but that periodical was al’ ready in the throes of dissolution, and did not long survive the financial panic of 1837. Poe’s only contribution to it was an elaborate review of Stephens’ “Incidents of Travel in Egypt, Arabia, Petraea, and the Holy Land.”

In the number of the Southern Literary Messenger which announced Poe’s retirement, Mr. White promised that he would “continue to furnish its columns from time to time with the effusions of his vigorous and powerful pen.” In the January number of the Messenger, 1837, which was the last under Poe’s editorship, appeared the first installment of “The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym,” which was continued in the February number, and afterward published in book form in New York and London. As usual with Poe’s works, it attracted more attention abroad than at home. It should be mentioned that he never relinquished his early interest in the Messenger, but wrote for it as long as he lived. As some of his earliest, so some of his latest, writings first appeared in that magazine.

Poe’s first residence in New York lasted from the winter of 1837 to the summer of 1838, when he removed to Philadelphia. Soon after his arrival in the Quaker City, he was asked by his old friend, Dr. N. C. Brooks, to write the leading article for the first number of The American Museum, a monthly magazine about to be started in Baltimore, and destined to add to the collection of dead magazines for which that city enjoys an unenviable reputation; in fact, while many magazines have been born and died in the Monumental City, it can boast of no living monthly, although it boasts of a population of 600,000 inhabitants.

Dr. Brooks suggested that Poe should write an article on Washington Irving. In answer to this request, Poe wrote a letter which Professor Harrison credits to an Englishman who claims to have “discovered” Poe, but he did not “discover” this letter, for I saw the original, in 1873, and printed it in my first “Life of Poe,” which was published in 1876, although the book was dated for the next year. From my work, the Englishman copied the letter into his Memoir, which was not published until 1880. Poe did not write the article on Washington Irving for Dr. Brooks, but the first number of the American Museum contained “Ligeia,” which its author regarded as his best story, because it displays the highest range of imagination. In this same magazine he published his clever satirical sketch, “The Signora Psyche Zenobia,” “Literary Small Talk,” and the dainty, airy, exquisite “Haunted Palace.” A Northern critic, who is not over-favorable to Poe, pronounces “Ligeia” a story “as faultless as humanity can fashion.”

Poe had several homes during the six years that he lived in Philadelphia — from 1838 to 1844 — but he resided for the longest time at Spring Garden, then a suburb of the city. It was there that Captain Mayne Reid visited him, and wrote a most delightful description of his home and family. The house was small, but furnished with much taste; flowers bloomed around the porch, and the singing of birds was heard. It was, indeed, the very home for a poet. “In this humble domicile,” says Mayne Reid, “I have spent some of the pleasantest hours of my life — certainly, some of the most intellectual. They were passed in the company of the poet and his wife — a lady angelically beautiful in person, and not less beautiful in spirit. No one who remembers the dark-haired, dark-eyed daughter of the South — her face so exquisitely lovely — her gentle, graceful demeanor — no one who has been an hour in her society, but will indorse what I have said of this lady, who was the most delicate realization of the poet’s rarest ideal. But the bloom upon her cheek was too pure, too bright for earth. It was consumption’s color — that sadly beautiful light that beckons to an early grave.

“With the poet and his wife there lived another person — Mrs. Clemm. She was the mother of Mrs. Poe, and one of those proud Southern women who have inspired the song and chivalry of their beautiful land. Mrs. Clemm was the ever-vigilant guardian of the house, watching over the comfort of her two children, keeping everything neat and clean, so as to please the fastidious eyes of the poet — going to market, and bringing home little delicacies that their limited means would allow; going to editors with a poem, a critique, or a story, and often returning without the much-needed money.”

This is a very pleasing glimpse at the home life of our poet, and all the more valuable, coming as it does, spontaneously from a foreigner. Such scenes show more truly a man’s real character than volumes of human analysis. I shall close this personal description of the poet with some particulars which Mrs. Clemm furnished me toward the close of her life, and which I took down in shorthand at the time: “Eddie had no idea of the value of money. I had to attend to all his pecuniary affairs. I even bought his clothes for him; he never bought a pair of gloves or a cravat for himself; he was very charitable, and would empty his pockets to a beggar. He loved Virginia with a tenderness and a devotion which no words can express, and he was the most affectionate of sons to me.”

Not long after Poe’s removal to Philadelphia, he was engaged as a contributor for The Gentleman’s Magazine, which was owned by William E. Burton, an English comedian, who is better remembered as an actor than as an editor and publisher. He drew immediate attention to the magazine by his powerful criticisms and strange, fascinating tales. Among the latter was “The Fall of the House of Usher,” which is regarded by most readers as Poe’s masterpiece in imaginative fiction; but, as already mentioned, he gave that preference to “Ligeia.” It has been said that “both have the unquestionable stamp of genius. The analysis of the growth of madness in one, and the thrilling revelation of the existence of a first wife in the person of a second, in the other, are made with consummate skill; and the strange, and solemn and fascinating beauty, which informs the style, and invests the circumstances of both, drugs the mind, and makes us forget the improbabilities of their general design.”

So well pleased was Burton with Poe’s contributions to The Gentleman’s Magazine, that, in May, 1839, he made him its editor. The pay was small — ten dollars a week — a paltry salary for a man of Poe’s genius and reputation. In the Autumn of 1840, Burton sold his magazine to George R. Graham, owner of The Casket. The two periodicals were merged into one under the name of Graham’s Magazine, with Poe as its editor. In two years he raised the circulation from 5,000 to 50,000. In the April, 1841, number of Graham’s appeared the extraordinary, analytical story, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” which first introduced him to French readers, and, also, made his name known to the French courts. A Paris Bohemian, having come across the story, dressed it up to suit the Parisian palate, published it in Le Commerce, as an original tale, under the name of “L’Orangotang.” Not long afterward, another French journal, La Quotidienne, published a translation of the story under another name. Thereupon Le Siècle charged La Quotidienne with having stolen said feuilleton from one previously published in Le Commerce. This led to a war of words between the editors of La Quotidienne and Le Siècle. The quarrel became so warm that it was taken to the law courts for settlement, where the aforesaid Bohemian proved that he had stolen the story from Monsieur Edgar Poe, an American writer. It was shown that the writer in La Quotidienne was himself an impudent plagiarist, for he had taken Monsieur Poe’s story without a word of acknowledgment; while the editor of Le Siècle was forced to admit that not only had he never read any of Poe’s works, but had not even heard of him. The public attention having been thus directed to Poe, his best tales were translated by Madame Isabelle Mennier, and published in several French magazines. The leading Parisian journals showered praises upon our author for the remarkable power and amazing ingenuity displayed in these tales. Many years afterward, Charles Baudelaire, having thoroughly imbued himself with the spirit of Poe’s prose writings, published a translation of them in five volumes. Poe is the only American author who is known, or, at least, popular, in France; and that he is known there is due, in a great measure, to the patient industry of Baudelaire.

“The Murders in the Rue Morgue” was followed, in November, 1841, by “The Mystery of Marie Roget,” in which the scene of the murder of a cigar girl, named Mary Rogers, in the vicinity of New York, was transferred to Paris, and, by a wonderful train of analytical reasoning, the mystery that surrounded the affair was completely disentangled. These, and a succeeding story, “The Purloined Letter,” are the most ingenious tales of ratiocination in the English language, and were the foundation of the modern detective story, so successfully carried out by Conan Doyle, the creator of “Sherlock Holmes,” Robert Louis Stevenson and others, who have frankly admitted their indebtedness to Poe. It will be interesting to know that Monsieur G—, the Prefect of the Parisian police, who is mentioned in these stories, was Monsieur Grisquet, for many years Chief of the Paris Police, who died in February, 1866.

The most extraordinary of Poe’s successful efforts at ratiocination was that in which he pointed out what must be the plot of Dickens’ celebrated novel, “Barnaby Rudge,” when only the beginning of the story had been published. In the Philadelphia Saturday Evening Post of May 1, 1841, Poe printed what he called “a prospective notice” of the novel, in which he used the following words:

“That Barnaby is the son of the murdered man may not appear evident to our readers; but we will explain: The person murdered is Mr. Reuben Haredale. His steward (Mr. Rudge, Senior), and his gardener, are missing. At first both are suspected. ‘Some months afterward,’ in the language of the story, ‘the steward’s body, scarcely to be recognized, but by his clothes and the watch and the ring he wore, was found at the bottom of a piece of water in the grounds, with a deep gash in the breast, where he has been stabbed by a knife,’ etc., etc.

“Now, be it observed, it is not the author himself who asserts that the steward’s body was found; he has put the words in the mouth of one of his characters. His design is to make it appear in the dénouement that the steward, Rudge, first murdered the gardener, then went to his master’s chamber, murdered him, was interrupted by his (Rudge’s) wife, whom he seized and held by the wrist, to prevent her giving the alarm, that he then, after possessing himself of the booty desired, returned to the gardener’s room, exchanged clothes with him, put upon the corpse his own watch and ring, and secreted it where it was afterward discovered at so late a period that the features could not be identified.”

Readers who are familiar with the plot of “Barnaby Rudge,” will perceive that the differences between Poe’s preconceived ideas and the actual facts of the story are immaterial. Dickens expressed his admiring appreciation of Poe’s analysis of “Barnaby Rudge.” He would not have expressed the same appreciation of Poe’s opinion of him, when reviewing the completed novel. At the time when Charles Dickens was the most popular writer in the world, Edgar Poe (who could never be made to bow his supreme intellect to any idol) boldly declared that he “failed peculiarly in pure narrative,” pointing out, at the same time, several grammatical mistakes of the great Boz. He also showed that Dickens occasionally lapsed into a gross imitation of what itself is a gross imitation — the manner of Charles Lamb — a manner based in the Latin construction. He further showed that Dickens’s great success as a novelist consisted in the delineation of character, and that those characters were grossly exaggerated caricatures — all of which is now admitted by judicious readers; but it required considerable courage to announce such an opinion at the time when Poe proclaimed it at the height of Dickens’s popularity. When Dickens visited the United States in 1842, Poe had two long interviews with him. He made a lasting impression upon the impressible Boz, and when he made his last visit to this country in 1867-8, he called upon Mrs. Clemm, in Baltimore, and presented her with $150.00.

Poe’s restless spirit grew tired of the “endless toil” of the editorial work on Graham’sMagazine, and he endeavored to obtain more certain and more remunerative employment. His intimate friend and lifetime correspondent, F. W. Thomas, of Baltimore, author of “Clinton Bradshaw,” “East and West,” and other novels of some repute sixty or seventy years ago, had obtained a Government clerkship in one of the Departments in Washington. In 1842, Poe wrote to Thomas, expressing a wish to get a similar position, saying that he “would be glad to get almost any appointment — even a five hundred dollar clerkship — so that I have something independent of letters for a subsistence. To coin one’s brain into silver, at the nod of a master, is, I am thinking, the hardest task in the world.” At the conclusion of his letter, he says he hopes some day to have a “beautiful little cottage, completely buried in vines and flowers.” How fortunately for the world that Edgar Poe did not secure “even a five hundred dollar clerkship!” Had he settled down to the dull routine of official life in Washington, he would probably not have written “The Raven,” “Eureka,” “The Literati of New York,” “Ulalume,” “The Bells,” and other productions that form an imperishable portion of American literature.

About a year after Poe removed to Philadelphia, he collected his stories, including “Ligeia,” “The Fall of the House of Usher,” “The Ms. Found in a Bottle,” “Morelia,” “The Assignation,” and others less known, and published them, in 1840, under the title of “Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque.” The edition was small, and small was the notice it received from the press and the public. The publishers allowed Poe no remuneration for this first edition of his Prose Tales, and gave him only twenty copies for distribution. Two years after the book was issued, he was informed that the edition was not all sold, and that it had not paid expenses. Yet, within a few years, this same edition of these same tales has sold at a fabulous price at the book auctions in New York.

During his early residence in Philadelphia, Poe edited a work on Conchology which caused some controversy at the time, of little interest then, and of no interest now.

Although Poe’s own countrymen were slow to recognize his genius, he was quick in recognizing the genius of others, and in bestowing generous praise upon all deserving contemporaries. He was the first American critic to proclaim the genius of Mrs. Browning (then Miss Barrett) to the world; and when he collected his poems into a volume, the book was dedicated to her, as “To the noblest of her sex, with the most enthusiastic admiration, and with the most sincere esteem.” He was the first to introduce to American readers the then unknown poet, Tennyson, and boldly declared him to be “The noblest poet that ever lived,” at a time when the English critics had failed to discover the genius of the future Poet-Laureate. He discovered the morbid genius of Hawthorne, when the latter was, as he said of himself, “the most obscure literary man in America.” Poe’s estimate of Willis, Halleck, Cooper, Simms, Longfellow, and other contemporaries, was eminently just. He placed the last the first among American poets; the position which Poe himself now holds, in the opinion of the leading scholars of England, France and Germany. It should be added that he qualified this praise of Longfellow by declaring that he was over-rated as an original poet.

Edmund Clarence Stredman, who had only a half-hearted appreciation of Poe, was honest enough to say that he “was a critic of exceptionable ability,” and agreed with James Russell Lowell that “his more dispassionate judgments have all been justified by time,” and that he “was a master in his own chosen field” of poetry. It has been well and truly said by an unknown writer in the Atlantic Monthly, of April, 1896, in an article on “The New Poe,” that until “we have a critic of the History of the Intellectual Development of this Country during the 19th Century... it is impossible to form any conclusions in regard to Poe that can be considered final.” Charles Leonard Moore, in a carefully written article in the Chicago Dial of February 16, 1903, pays a just tribute to Poe’s critical powers when he says: “Undoubtedly, Poe performed one of the most difficult feats of criticism. With almost unerring instinct, he separated the wheat from the chaff of his contemporary literature.” In this same article, Mr. Moore declares that “Poe is the most sublime poet since Milton — a sublimity which stirs even in his most grotesque and fanciful sketch. It rears full-fronted in the concluding pages of the ‘Narrative of A. Gordon Pym.’ It thrills us in the many-colored chambers of ‘The Mask of the Red Death.’ It overwhelms us with horror in ‘The Murders of the Rue Morgue.’ It is sublime and awe-inspiring in ‘Ligeia,’ ‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ in ‘Ulalume,’ and ‘The Raven.’ He reaches a climax of almost too profound thought in ‘The Colloquy of Monos and Una,’ ‘The Power of Words,’ and ‘Eureka.’ His sublimity accounts for his fate with the American public. A true Democracy, it abhors greatness and ridicules sublimity.” Mr. Moore says, further: “The total effect of his work is lofty and noble. His men are all brave and his women are pure. He is the least vulgar of mortals. In every land which boasts of literary culture, or civil enlightenment, Poe’s poems and tales are read, and he is regarded as a distinctive genius.”

The first four years of Poe’s residence in Philadelphia — 1838-42 — were the most productive of his literary life. These four years show the most extraordinary amount of first-class literary work that has even been accomplished in this country in the same space of time. Unfortunately, the author of all of this fine, artistic work received only a pittance as his pecuniary reward. All this time he was poor — desperately poor — and in the last of these four years of surpassing achievements, a great affliction came upon him — his wife — his idolized Virginia — broke a blood-vessel in singing. From that hour until her death, five years afterwards, the delicate condition of his wife’s health was a constant source of care and anxiety to the devoted husband. While struggling against poverty, and in the midst of the most disheartening surroundings, his wonderful imagination filled his soul with dreams of princely palaces and royal gardens, in which lived and moved forms of more than earthly beauty.

Friends and foes alike agree in testifying to Poe’s tender devotion to his darling wife, “in sickness and in health.” The most unrelenting of his enemies mentions having been sent for to visit him “during a period of illness, caused by protracted and anxious watching at the side of his sick wife.” George R. Graham, in a generous defense of the dead poet, said, “I shall never forget how solicitous of the happiness of his wife and mother-in-law he was, whilst editor of Graham’s Magazine. His whole efforts seemed to be to procure the comfort and welfare of his home... His love for his wife was a sort of rapturous worship of the spirit of beauty which he felt was fading before his eves. I have seen him hovering over her, when she was ill, with all the fond fear and tender anxiety of a mother for her first-born; her slightest cough causing in him a shudder, a heart-chill that was visible. I rode out one summer evening with them, and remembrance of his watchful eyes, eagerly bent upon the slightest change of hue in that loved face, haunts me yet as the memory of a sad strain. It was this hourly anticipation of her loss that made him a sad and thoughtful man, and lent an undying melody to his undying song.”

In the spring of 1842, Poe retired from Graham’s Magazine. His reputation as the most brilliant editor in America; his fame as a poet and as a writer of purely imaginative tales, and his success in making Graham’s Magazine the most profitable in the United States, made him feel the very natural ambition of having a magazine of his own — a magazine in which he would be perfectly untrammeled, entirely free from the control of timid publishers. With this object, he issued the prospectus of a magazine to be called The Stylus. Contributors and illustrators were engaged; the day was fixed for the appearance of the first number; everything was ready but the most important thing of all — the money to publish it. So the enterprise was temporarily abandoned, to be taken up again and again until the close of Poe’s life.

In 1843 won the hundred dollar prize offered by the Dollar Magazine, of Philadelphia, for the best short story. It was one of his most popular tales, “The Gold Bug,” which gained this prize. It is founded on the discovery of the supposed buried treasure of Captain Kyd. The story displays a remarkable illustration of Poe’s theory that human ingenuity can construct no enigma which the human mind, by proper application, cannot solve. The chief interest centres on the solution of an abstruse cryptogram.

This one hundred dollar prize came when Poe was much in need of money, for after leaving Graham’s Magazine, he was without any regular work during the rest of his stay in Philadelphia. He wrote for James Russell Lowell’s short-lived magazine, The Pioneer, and some notable reviews for Graham’s Magazine. After the issue of three numbers, The Pioneer was discontinued, and Lowell was very much distrest because he could not pay his contributors, among them Poe, who, although wanting the money, wrote to the unfortunate editor: “As for the few dollars you owe me ($35.00), give yourself not one moment’s concern about them. I am poor, but must be much poorer, indeed, when I even think of demanding them.” Lowell requited Poe’s generosity very ungratefully, when, in A Fable for the Critics, he thus characterized his former friend:

There comes Poe with his Raven, like Barnaby Rudge

Three-fifth of him genius and two-fifth sheer fudge —

Who has written some things quite the best of their kind,

But the heart somehow seems all squeezed out by the mind.

Poe showed a great deal of ‘‘heart” when he refused to ask Lowell for money due him for his contributions to The Pioneer. In return for Lowell’s base ingratitude, Poe denounced him as “one of the most rabid of the Abolition fanatics — a fanatic simply for the sake of fanaticism.”

In April, 1844, Poe again removed to New York, hoping to find a better field for his literary work than Philadelphia had proved since he retired from Graham’s Magazine. On Saturday, April 13, within a week after his arrival in New York, the Sun, of that city, published his famous “Balloon Hoax.” In this extraordinary narrative, Poe anticipated the wonderful achievements of the twentieth century in crossing the Atlantic. It created an immense sensation at the time. In the same month, “A Tale of the Ragged Mountains” was published in Godey’s Lady’s Book, and, in June, his poem, “Dreamland,” in Graham’s Magazine.

In the spring of 1844, Poe resumed his correspondence with James Russell Lowell. From the first of these letters, dated May 24, 1844, we learn that six of his stories were in the hands of different editors waiting publication. Poe was an industrious, painstaking, fascinating writer; he was known as the author of some of the best short stories that had ever been published in an American magazine yet, after ten years of unceasing work, he could not find a ready market for his writings, and when published, he received a wretched remuneration for the highest kind of imaginative prose — compositions that have taken a front rank in the literature of the world.

In October, 1844, Poe was engaged by N. P. Willis as assistant on the Evening Mirror. For a small weekly salary, the greatest American writer was obliged to drudge seven hours in a corner of the Evening Mirror office — from nine to four — “ready to be called upon for any of the miscellaneous work of the day.” Willis furnishes the following tribute to his gifted “assistant”: “With the highest admiration for his genius, and a willingness to let it atone for more than ordinary irregularity, we were led by common report to expect a very capricious attention to his duties, and, occasionally, a scene of violence and difficulty. Time went on, however, and he was invariably punctual and industrious. With his pale, beautiful, intellectual face, as a reminder of what genius was in him, it was impossible, of course, not to treat him with deferential courtesy, and, to our occasional request that he would not probe too deep in a criticism, or that he would erase a passage colored too deeply with his resentments against society and mankind, he readily and courteously assented — far more yielding than most men, we thought, on points so excusably sensitive. With a prospect of taking the lead in another periodical, he, at last, voluntarily gave up his employment with us, and, through all this considerable period, we had seen but one presentment of the man — a quiet, patient, industrious, and most gentlemanly person, commanding the utmost respect, and good feeling by his unvaring deportment and ability.”

The other periodical, in which he was “to take the lead,” was The Broadway Journal, a weekly paper which had been started in New York in January, 1845. In March, of that year, Poe became associate editor and one-third owner. In July, when the paper was slowly dying, Poe became its sole editor. Looking over the volumes of the Broadway Journal, I was astonished to see so many highly finished articles from his pen, at the very time, too, when his adored wife was ill, almost dying, and when he himself was in poor health, and harassed by cares and troubles of all kinds.

While Poe was still working for N. P. Willis as assistant on the Evening Mirror, he electrified the world by the publication of The Raven. This famous poem was originally published in The American Review — a New York Whig Journal of Politics, Literature, Art, and Science — in the number for February, 1845. It has been truly said that the first perusal of The Raven leaves no distinct impression upon the mind, but fascinates the reader with a strange and thrilling interest. It produces upon the mind and heart a vague impression of fate, of mystery, of hopeless sorrow. It sounds like the utterance of a full heart, poured out — not for the sake of telling its own sad story to a sympathetic ear — but because he is mastered by his emotions, and cannot help giving vent to them. It more resembles the soliloquies of Hamlet, in which he betrays his struggling thoughts and feelings, and in which he reveals the workings of his soul, stirred to its utmost depth by his terrible forebodings.

Dr. Henry E. Shepherd, the distinguished Southern scholar, critic, and educationalist, has furnished the most admirable study of The Raven that has ever been written. After assigning to Poe a place in that illustrious procession of classical poets, which includes Milton, Ben Johnson, Herrick, Shelley and Keats, he says of The Raven: “No poem in our language presents a more graceful grouping of metrical appliances and devices. The power of peculiar letters is evolved with a magnificent touch; the thrill of the liquids is a characteristic feature, not only of the refrain, but throughout the compass of the poem; their ‘Linked sweetness long drawn out,’ falls with a mellow cadence, revealing the poet’s mastery of those mysterious harmonies which lie at the basis of human speech. The continuity of the rhythm, illustrating Milton’s ideal of true musical delight, in which the sense is variously drawn out from one verse into another; the alliteration of the Norse minstrel and the Saxon bard; the graphic delineation and the sustained interest, are some of the features which place The Raven foremost among the creations of a poetic art in our age and clime.” Dr. Shepherd, continuing his beautiful address, proceeded to show “the versatile character of Poe’s genius, the consummate, as well as the conscious, art of his poetry, the graceful blending of the creative and the critical faculty — a combination perhaps the rarest that the history of literature affords — his want of a deference to prototypes or models, the chaste and scholarly elegance of his diction, the Attic smoothness and the Celtic magic of his style... Much of his work will perish only with the English language. His riper productions have received the most enthusiastic tributes from the sober and dispassionate critics of the Old World. I shall ever remember the thrill of grateful appreciation with which I read the splendid eulogium upon the genius of Poe in The London Quarterly Review,