Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Hollitzer Wissenschaftsverlag

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Deutsch

Eduard Strauss I (1835–1916), the youngest of the three Strauss brothers – and hence the 'third man' of the family, has always been overshadowed by his siblings Johann II and Josef. However, he was the longest lived and most widely travelled of the three and, as sole conductor and manager of the Strauss Orchestra for thirty years, brought authentic performances of his family's music to audiences in hundreds of towns and cities in Europe and North America. At home in Vienna he made an invaluable contribution to the city's musical and cultural life, while having at the same time to cope with continual tensions and problems within the Strauss family.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 592

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

LEIGH BAILEY

EDUARD STRAUSS:THE THIRD MAN OF THE STRAUSS FAMILY

To the memory of my mother

Layout and cover: Nikola Stevanović

Printed and bound in the EU

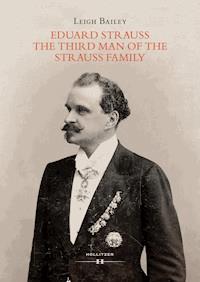

Cover image: Family archive Dr. Eduard Strauss

Frontispiece: Family archive Dr. Eduard Strauss (photo);The Johann Strauss Society of Great Britain (caption).

Leigh Bailey: Eduard Strauss: The Third Man of the Strauss Family

Vienna: HOLLITZER Verlag, 2017

© HOLLITZER Verlag, Wien 2017

Hollitzer Verlag

a division of

Hollitzer Baustoffwerke Graz GmbH, Wien

www.hollitzer.at

All rights reserved.

Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form by any means, digital, electronic or mechanical, or by photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a Web site without prior written permission of the publisher.

Responsibility for the contents of the various articles and for questions of copyright lies with the authors.

In the case of outstanding, justified claims, we request to be notified by the rights owner.

ISBN 978-3-99012-357-7 eBook

FOREWORD

Here it is, at long last, what Strauss enthusiasts all over the world have been eagerly awaiting: the first comprehensive biography of my great-grandfather, Eduard Strauss I (1835–1916). And, as expected, it shows ‘handsome Edi’ in a new light, in a way that does him justice.

The family he was born into was probably already ‘broken’. It is no surprise that he became a ‘difficult gentleman’, as his famous brother Johann Strauss II put it. As the last of the three sons of Johann Strauss I, a genius who died young, he had, at the bidding of his mother Anna, to enter the ‘family business’. Always overshadowed by his brother Johann, ten years older than him, after the early death of his other brother Josef, eight years his elder, Eduard took sole charge of the Strauss Orchestra, an outstanding ensemble. As a result he was the one who was also responsible for spreading the family’s music – as far as the USA.

Both brother Johann and the Viennese press tended to dismiss Eduard as the mere ‘also ran’ of the family, regarding him as a ‘nonentity’. He preferred to perform abroad rather than at home, and grew into an embittered old man with some pedantic traits.

Having himself grown up with little in the way of love, he was apparently incapable of providing love, care and a feeling of security in his own family. His sons – my great-uncle and my grandfather – developed into happy-go-lucky, self-centred spendthrifts, who deprived their father of a fortune and caused him quite serious financial problems when he was already in his sixties. Johann Strauss II reacted in a cool, wait-and-see manner, and did not help his brother Eduard. However, Eduard Strauss I was able to build up a second fortune, which he then tried to ensure would be kept safe by means of a will of over one hundred pages and with the most detailed and precise stipulations. For reasons which I do not know he made no provision for the children of his younger son Josef – that is to say my uncle, my aunt and my father. In 1907 Eduard burned the entire musical archive of the Strauss Orchestra; this took two visits each lasting several hours to furnaces in Vienna. Why he did this has remained a mystery, which the present author now tries to explain on a factual basis.

On behalf of my family I would like to thank Leigh Bailey warmly for his years of meticulous research on Eduard Strauss I, which have now culminated in the appearance of this impressive work. It is certainly rewarding to read this book, even if you are not a Strauss specialist.

Vienna, November 2016

Dr. Eduard Strauss

PREFACE

It may seem self-evident that the music and the composers of the Strauss dynasty are known throughout the world. Nevertheless, despite their enduring popularity, at the same time they actually remain largely unknown. A small number of compositions by the Strausses are played time and time again, but the vast majority of their dances are hardly ever performed or listened or danced to. Everyone knows the name Johann Strauss, but how many music lovers are aware that there were three musicians with this name in the family? Or could say how many Josefs and Eduards there were in the dynasty, and whether Richard Strauss has a place in its family tree? There are so many stories and anecdotes about the Strauss family, many of them spread by the Strausses themselves, that often a considerable amount of research is required to separate fact from fiction. But, as is so often the case, truth is stranger and even more fascinating than fiction.

By far the most famous member of the Strauss dynasty is the Johann Strauss who composed The Blue Danube waltz. His father, also Johann Strauss, founded the family business and made the name ‘Strauss’ a worldwide brand, but the only composition of his that is still played at all frequently is the Radetzky March. His nephew, also Johann Strauss, tried to establish himself as a composer and conductor of Viennese dance music and operetta in the years around 1900, but today it is only devoted Strauss enthusiasts and specialists who are even aware of his existence. So the Johann Strauss the world knows (or thinks it knows) best needs to be referred to as Johann Strauss II to avoid any confusion. And he had two brothers, Josef and Eduard, who were important composers and conductors in their own right and made an invaluable contribution to the family business. But they too have been completely overshadowed by their brother. Ironically, Josef’s best known composition is probably the piece that he wrote jointly with Johann, the Pizzicato Polka. But at least the story of his life has been told in two full-length biographies. Amazingly, the story of Eduard’s life has up to now been told only piecemeal in individual chapters of books basically concerned with the biography of eldest brother Johann. And yet Eduard was the longest lived of the family, the most widely travelled, and was in sole charge of the Strauss Orchestra for thirty of the seventy-four years of its existence. So this book is intended to fill this gap a full century after the death of Eduard, the ‘third man’ of the Strauss family. At the same time, to tell the story of his life is also to tell the story of the family from a new perspective and thus to throw new light not only on the relationship between the ‘third man’ and the ‘first man’ of the trio of Strauss brothers but in doing so also to provide a new view of Johann Strauss II, the star of the dynasty.

There is no lack of primary material on the Strauss family. The Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, the Vienna municipal library, has a vast collection not just of their music but also of their letters and other documents relating to them. Thanks to decades of work by Franz Mailer, much of this material, as well as material from other sources, is now conveniently available in printed form in the ten-volume collection Johann Strauss (Sohn): Leben und Werk in Briefen undDokumente, published between 1983 and 2007 under the auspices of the Johann Strauss Society of Vienna. All the material which Mailer collected on the members of the Strauss dynasty, including Eduard Strauss, has now been entrusted to the Music Department of the Danube University in Krems, Austria, where it is kept in the university library and was made freely available to me by the chair of the department, Dr Eva Maria Stöckler, and her colleagues. My thanks therefore go to them and above all – albeit, unfortunately, posthumously, to Franz Mailer, without whose work it would have taken much, much longer for me to write this biography. My thanks also go to the Wienbibliothek, and especially to Norbert Rubey, the official Strauss specialist of the City of Vienna, with whom I have had long and fruitful discussions and who has provided a wealth of invaluable advice and detailed information, as well as making many practical suggestions. Dr Eduard Strauss, the great-grandson of my ‘biographee’, the current head of the Strauss family and president of the Vienna Institute for Strauss Research, has provided invaluable support, taking a great interest in my work, reading my manuscript with great care, correcting mistakes and making many suggestions for improvements. His wife Susanne is a pharmacist, and has made a meticulous transcription and analysis of the book of prescriptions which Eduard Strauss kept in the last thirty years of his life and which is now in the Wienbibliothek. To them both go my thanks not only for many stimulating discussions but also for their hospitality on numerous occasions.

Interest in the music and lives of the Strauss family is of course worldwide, and this is reflected in the Strauss societies which have been established in many countries. A former chairman and now Honorary Life President of The Johann Strauss Society of Great Britain, Peter Kemp, the author of the standard history of the Strauss dynasty, has followed the progress of the biography, reading the manuscript and making detailed comments. I am extremely grateful to him for having taken such trouble. I should also like to thank the society’s current chairman, John Diamond, for providing valuable material on Carl Michael Ziehrer. My thanks also go the chairman of the German Johann Strauss Society, Ingolf Rossberg, for providing important material from the society’s journal and archive, especially the material painstakingly collected by Alfred Dreher on Eduard Strauss’s tours of Germany. I am also indebted to Friedhelm Kuhlmann, a member of the society’s committee, who has made available to me the results of his research on Oscar Fetrás, a fellow director of music and trusted friend of Eduard Strauss. On the other side of the Atlantic, the former Johann Strauss Society of New York collected a wealth of material on Eduard Strauss’s two American tours, and I am extremely grateful to its erstwhile president, Jeroen H.C. Tempelman, for making available to me the results of his members’ researches.

I have also been encouraged throughout the project by the interest taken in the biography by colleagues and friends. Some of them have also provided valuable advice and material on specific aspects, and in this connection I would like to thank especially Helmut Reichenauer for his help and advice in selecting illustrations, Ian Magadera for the benefit of his expertise in biographies, Kerry Tattersall for important background information on the Habsburg dynasty and court, and Waldemar Zacharasiewicz for material on Vienna and the Strausses from his own field of research, imagology.

Finally, I would like to dedicate this book to my mother. She loved the music of the Strausses and took a keen interest in the progress of this biography. Unfortunately she did not live to see it completed.

Vienna, November 2016

Leigh Bailey

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author wishes to thank the following for their permission to reproduce illustrations from their personal archives: Peter Kemp, Ian Magedera, Norbert Rubey and Dr. Eduard Strauss. Illustrations belonging to the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (Austrian National Library), the Wienbibliothek im Rathaus (Vienna Library in the City Hall) and the Wien Museum are reproduced with the permission of the respective institutions. The source of each illustration is shown below it in the text.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD BY DR EDUARD STRAUSS

PREFACE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FAMILY TREE OF THE STRAUSS FAMILY

PRELUDE: EDUARD STRAUSS’S VIENNA (1835–1916)

The musicians of the Strauss dynasty – the development of the Viennese ball – Vienna as the imperial capital and residence, its atmosphere and development during Eduard Strauss’s lifetime – his two addresses in the city.

1 THE STRAUSS FAMILY (1835)

Vienna in March 1835 – death of Franz I – birth of Eduard Strauss – his family and his father’s career and private life.

2 CHILDHOOD AND EDUCATION (1835–1849)

Life in the Strauss family home – Eduard’s education and his experiences during the 1848 revolution.

3 MUSICAL DÉBUT (1850–1862)

Eduard’s plans and interests after leaving school – Strauss family life in the 1850s – Eduard decides to train as a musician, his début as a harpist with the Strauss Orchestra, further musical education and first appearance as a conductor.

4 HANDSOME EDI, THE WALTZ PRINCE (1862–1869)

Eduard Strauss’s role in the family business and relations with brothers Johann and Josef – press hostility to Eduard – visit to Russia – three Strauss orchestras and the golden years of the dynasty.

5 FROM FAMILY CRISIS TO TWO IMPERIAL TITLES (1869–1872)

Tensions between Johann, Josef and Eduard – deaths of mother Anna and Josef – Johann turns to operetta and Eduard assumes sole responsibility for the Strauss Orchestra, subsequently succeeding Johann as Imperial-Royal Director of Music for Court Balls.

6 SUCCESSES AND SETBACKS IN JOHANN’S SHADOW (1872–1878)

Busy Carnival seasons – more tension between Eduard and Johann, especially over performances for the World Exhibition in Vienna in 1873 – Eduard and the Strauss Orchestra begin to find their dominant position in Vienna hard to maintain.

7 SUMMERS ON TOUR, WINTERS IN VIENNA (1878–1885)

Eduard reorganizes the Strauss Orchestra and begins his series of summer tours, especially to Germany, while concentrating on his Sunday afternoon concerts in the Musikverein in Vienna during the winter.

8 FROM LONDON TO NEW YORK (1885–1890)

First visit to London and extensive summer tours of Germany – Eduard’s winter concerts in Vienna with appearances by Johann and first performances of his dances – problems with younger son Josef – recordings for Edison’s phonograph – arrangements for first visit to America.

9 FAME ABROAD, PROBLEMS AT HOME (1890–1896)

Long and successful tour of the USA and Canada – tensions with brother Johann and more problems with son Josef – visit to Russia not entirely a success – second visit to London with command performance for Queen Victoria in Windsor Castle and return via Holland and Germany – improvement in relations with Johann.

10 FROM FAMILY CATASTROPHE TO TWICE-EARNED RETIREMENT (1896–1901)

Eduard Strauss’s role in Vienna’s musical life at the imperial court and in the concert hall – Eduard learns that his wife and sons have misappropriated virtually all his savings – third visit to London and further lengthy tours of Germany in order to rebuild his fortune – death of Johann and Eduard’s bitterness at being completely ignored in his will – Eduard’s elder son Johann attempts to launch his own musical career – second tour of America highly successful, but ending with a serious shoulder injury and the disbandment of the Strauss Orchestra.

11 MEMOIRS, BURNINGS AND BITTERNESS (1901–1907)

Eduard’s retirement increasingly beset by both health and family problems – official honours and belated recognition of his achievements by the Viennese press – writes his memoirs – decides to burn virtually the entire musical archive of the Strauss Orchestra.

12 THE LAST YEARS (1908–1916)

Increasing health problems – Eduard becomes preoccupied with his will, determined to ensure that neither his wife and sons nor their creditors can get their hands on his money – his birthdays lead to a wave of interest and congratulations – final illness, death and burial in a grave of honour in Vienna’s Central Cemetery.

POSTLUDE: EDUARD STRAUSS’S MUSICAL LEGACY

Obituaries and legacy – Eduard’s place in the Strauss dynasty – his achievements as conductor and composer – performances of his works.

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX OF NAMES

INDEX OF COMPOSITIONS BY EDUARD STRAUSS

PRELUDE:EDUARD STRAUSS’S VIENNA(1835–1916)

At nearly eighty-two years, Eduard Strauss’s life was the longest among the musicians of the Strauss dynasty. He outlived his eldest brother Johann (1825–1899), the undoubted star of the family, by several years, while the lives of his father Johann (1804–1849) and his elder brother Josef (1827–1870) were cut short by illness, acute in the case of the former, chronic in the case of the latter. Nor could the two professional musicians of the family in subsequent generations, Eduard Strauss’s son Johann (1866–1939) and grandson Eduard (1910–1969), match his longevity.1

Eduard Strauss was born in Vienna on 15 March 1835 and died there on 28 December 1916. For more than forty years of his life he held the honorary title of Imperial-Royal Director of Music for Court Balls, and for nearly thirty of those years actually performed at these events, much longer than the total time during which the three other holders of the title – his father, his brother Johann, and Carl Michael Ziehrer – were active in this role. As if to stress his link with the Habsburg dynasty, the span of Eduard Strauss’s life coincides almost exactly with the reigns of two emperors: Ferdinand, who came to the throne just two weeks before he was born, and his nephew, Franz Joseph, who died just over one month before Eduard did. Unlike eldest brother Johann, who became a German citizen in order to divorce his second and marry his third wife, Eduard remained an Austrian citizen throughout his life. However, the state he was born in was called the Austrian Empire, founded by Ferdinand’s father, Franz, in the course of the Napoleonic Wars when it became clear that the Holy Roman Empire was about to disappear and his imperial title with it; the state in which he died was called the Austro-Hungarian Empire, founded by Franz Joseph in 1867 in an attempt to keep his realm together by placating the powerful Hungarian minority with a considerable degree of autonomy in the wake of Austria’s defeat at the hands of Prussia the year before. As a teenager Eduard Strauss experienced the revolution of 1848, as an old man the outbreak of the First World War – although not its end and the political turmoil that accompanied it, so that he was spared witnessing the break-up of the Habsburg Monarchy and the end of Austria as he knew it. The eight decades he lived through were of course also a period of rapid technological development: his early years saw the opening of Austria’s first railways, a form of transport without which the extensive concert tours he made in Europe and North America would have been virtually impossible. Later came the harnessing of electrical energy and inventions such as the telephone and the phonograph, all of them commemorated in the titles and music of some of Eduard’s dance compositions.

What did not change in the course of Eduard Strauss’s long life was the status of Vienna: it was the Imperial-Royal Capital City of the Empire and Residence of the Emperor.2 It was the presence of the imperial court and government that gave the city its characteristic atmosphere; it was a place very much aware of its own importance, teeming with aristocrats, civil servants and soldiers, together with the host of tradesmen and servants who catered for their needs. In the course of the nineteenth century the Austrian capital also became an important centre of industry and finance. This concentration of the corridors of power meant that it was a city where intrigue flourished, but Vienna was above all a city of music. The Habsburgs, many of whom were themselves practising musicians, were well aware of the political value of culture, but suspicious of forms of art that could be used as a vehicle for subversive ideas, with the result that anything that could be regarded as a national Austrian literature was a very late arrival on the cultural scene. Music was much safer, and the fact that it was not dependent on language was a major advantage for both performers and listeners in a multilingual empire. Because of the dominant position of the court and the aristocracy in the musical life of Vienna, regular public concerts and permanent concert halls were not provided until well into the nineteenth century. However, by then balls and dance music had established themselves as a distinctive feature of Viennese life. Interestingly, the typical Viennese ball owes its existence to a ban imposed by Empress Maria Theresa on the masked Carnival processions traditionally held in the streets; she was afraid that such events could serve as a cover for immoral or politically subversive behaviour.3 So the music and the dancing moved indoors, and everything became more orderly and more elegant – worthy, in fact, of an imperial capital. There even evolved a dance form and the music to go with it which seemed to epitomize the atmosphere of these balls and indeed that of the whole city: the Viennese waltz.

The most famous of the four hundred or so waltzes that the Strauss dynasty composed is undoubtedly The Blue Danube by Eduard’s eldest brother Johann. But it is worth noting that the river that the Strauss brothers grew up with was very different from the one that flows past Vienna today. In the early nineteenth century the Danube split into a maze of meandering channels after rounding the hills of the Vienna Woods to the north of the city. The suburb where Eduard lived was between the Donaukanal (Danube Channel), the arm of the Danube that flowed beside the old city centre, and the labyrinth of islands and inlets surrounding the main stream of the river. It was an area that was liable to be flooded, and after two such catastrophic floods in 1830 and 1862 the decision was taken to regulate the river by digging a new, straight channel for it and leaving a flat strip of undeveloped land on the far side where floodwater could spread without causing damage. The project was carried out in the 1870s, several years after the famous waltz was first performed.

It was not only the Danube and the area around it that underwent considerable change during Eduard Strauss’s long life: the size and appearance of the whole of Vienna was transformed. When he was born Vienna had a population of around 400,000; at the time he died it was over 2,200,000. While he was growing up the old city centre was still surrounded by walls and could only be entered through narrow gated archways; these defensive works were surrounded on three sides by an open space, the Glacis, most of which was used as a recreation area by the Viennese, while some parts were used as drill and parade grounds by the military. The Donaukanal flowed past the fourth side, and it was in a house in the suburb on its far bank that Eduard Strauss was born and lived for the first fifty years of his life. This suburb was one of a ring of such settlements around the old city and its ring of defences. These suburbs, known as the Vorstädte, were in turn surrounded by a defensive rampart, the Linienwall, originally built in the early eighteenth century as protection against raids by Hungarian insurgents; in the nineteenth century it was used as a customs barrier, with the so-called ‘consumption tax’ being levied on goods passing through the gateways in it. Outside this rampart there was another ring of suburbs, the Vororte; for most of the nineteenth century these were still villages with a distinctly rural atmosphere, many of them popular with the Viennese – including Eduard Strauss – as places to stay in the summer. The inner ring of suburbs was incorporated into the City of Vienna in the 1850s, the outer ring in the 1890s. The result was Greater Vienna, the capital city of an empire of fifty million people.

Throughout his long life Eduard Strauss was a resident of Vienna and moved house only once.4 His first address was both the family home of the Strausses and the headquarters of their music business. He was the last of them to leave it, in 1886. The house itself, whose history could be traced back at least to the seventeenth century, was demolished in 1911 to make way for much grander buildings; it was a fate that befell hundreds of houses in Vienna as the city grew. As turn-of-the-century satirist Karl Kraus put it, ‘Vienna is being demolished into a metropolis.’5 There were, though, plenty of areas that offered greenfield sites, the most prestigious of which was the open ground between the old city, whose walls were pulled down between 1858 and 1864, and the inner suburbs. In the centre of this a spacious tree-lined boulevard, the Ringstrasse, was laid out, flanked by grandiose buildings to house the city’s and the empire’s most important political, cultural and economic institutions. On it and the new streets laid out alongside it luxurious town palaces for the wealthiest bankers and industrialists and elegant apartment houses for the not quite so wealthy were built, and it was to an apartment in one such building, situated behind the Parliament and one block away from the Town Hall, that Eduard Strauss and his family moved. He stayed there even after breaking completely with his wife and sons in the wake of a family scandal in the late 1890s. For the remaining years of his life he lived there with his housekeeper who, assisted by a cook, looked after him in his old age and nursed him on the frequent occasions when he fell seriously ill.

1THE STRAUSS FAMILY(1835)

Vienna, 1835. The first weeks of the year were marked, as usual, by the balls and festivities of the Carnival season. With several such events taking place every evening, the musical directors and their orchestras were kept more than busy. Johann Strauss was no exception. On 2 March, the last Monday of Carnival, he would, according to an announcement in the Wiener Zeitung, the official gazette, be in charge of the music for third and last grand festive Flora Ball at Dommayer’s Casino in Hietzing, then still a village just beyond Schönbrunn Palace and its extensive park. On the same evening he was also due to appear at Sperl’s establishment on the other side of town in the Leopoldstadt suburb, where he was to conduct a performance of his latest waltz. By this time the carnival atmosphere was, however, somewhat subdued by the news that the emperor, Franz I, was seriously ill. He had already received the last sacrament and thus, in line with established procedure, the two court theatres, the Burgtheater and the Kärntnertortheater – for plays and operas respectively, remained closed. On Tuesday 3 March the first column of the front page of the Wiener Zeitung carried the announcement that ‘It has pleased God the Almighty to call from this world His Imperial-Royal Majesty the Emperor and King Franz the First, the most dearly beloved father of our country.’ The announcement was signed by Ferdinand, his son and successor, as was the letter printed below it, which was addressed to Prince Colloredo, the Lord High Chamberlain, and ended by commanding him ‘to take appropriate measures to ensure that every form of entertainment incompatible with the general state of mourning be called off in all provinces’.1

The imperial court went into mourning for six months, but with the end of Lent and the celebration of Easter – and the new emperor’s birthday, which in that year fell on Easter Sunday, cultural and musical life in Vienna began to get back to normal. On Easter Monday the two court theatres resumed their daily performances, and on the same day one of Vienna’s most popular establishments, the Tivoli pleasure grounds next to Schönbrunn park, opened for the summer season. Johann Strauss conducted his orchestra there on the following Thursday, while the next weekend saw his first appearance at Dommayer’s Casino. Over the following weeks the Wiener Zeitung carried frequent advertisements for his concerts at various venues, as well as for his two latest waltzes, available in a number of arrangements from piano solo to full orchestra. They could even be had in an arrangement for the czakan, a walking stick whose upper section could be detached and played like a recorder and which was a fashionable accessory in early nineteenth-century Vienna. That shows just how popular Strauss’s music was, as does the fact that all advertisements for his appearances and his compositions invariably printed his name in large, bold typeface. The name ‘Strauss’ had already become a valuable brand.

The spring of 1835 also saw two important events in Johann Strauss’s family life. On 15 March, just one day after his own thirty-first birthday, his wife Anna, then thirty-two years old, gave birth to a son, the sixth and last of the children the couple had together. He was named Eduard, and baptized in St Josef’s, the local parish church just across the street from the house where the Strausses lived, with Ferdinand Dommayer, the proprietor of the establishment in Hietzing where Strauss performed regularly, acting as godfather. Little more than two months later, on 18 May, Johann Strauss again became a father, this time of a daughter, Emilie. Her mother, Emilie Trambusch, was just twenty years old and a milliner. Strauss had probably got to know her a year or two earlier, and he was to have at least a further six children with her over the following nine years.2

The house where Eduard Strauss was born, and where he was to live for more than fifty years, was situated in the Leopoldstadt suburb of Vienna. Today it forms the city’s second district, and it is located just across the Donaukanal, the arm of the Danube which marks the river’s original course, from the first district, the old city centre. The suburb developed in the Middle Ages on a group of islands between the arms of the Danube. In the seventeenth century a Jewish ghetto had been set up there, and in the second half of the nineteenth century the district again became known as the Jewish quarter of Vienna – the ‘matzo island’, as the Viennese called it. However, in 1669 the Jews had been expelled, and two years later the suburb was named Leopoldstadt after the reigning emperor, Leopold I – until then it had been known simply as Unterer Werd, the ‘Lower Island’. Its location meant that it was where the men working on the boats and rafts that plied the Danube landed and stayed when they were in Vienna, so that it was also home to the inns that catered for them. The dances they brought with them and played in the inns were one of the most important influences in the development of the Viennese waltz. On the other side of the suburb, on the islands towards the main stream of the Danube, there were the Augarten palace and park and the Prater, an imperial hunting reserve. They were opened up to the public in 1766 and 1775 respectively by Joseph II, the reforming emperor, and soon became popular recreation areas for the Viennese. They also attracted restaurants, cafés and inns, which were soon offering various forms of musical entertainment for their patrons.

Johann Strauss’s father, Franz Borgias Strauss, had tried to make a living as the landlord of an inn in a street leading off the Donaukanal, just a few minutes’ walk from the house where Eduard was born. His business had its good years and its bad years, but it was the time of the Napoleonic wars with all the political and financial turbulence that they caused: the French army occupied Vienna twice, in 1805 and 1809, and two years later the Austrian state went bankrupt. When peace finally came in 1815, one of the measures the government took to stimulate the economy was to open up the brewing trade to anyone with sufficient capital, irrespective of whether they had been served an apprenticeship as a brewer. The beer price slumped and Franz Strauss’s hope of running his business profitably and being able to pay off his debts collapsed with it. On 5 April 1816 his body was found, washed up by one of the many arms of the Danube.

When Eduard Strauss wrote his memoirs, he commented that ‘all that the family knows about Johann Strauss’s childhood is that as a boy, when musicians played in the larger of the inn’s two rooms, Johann would crawl under a table to be able to listen to the musicians without his father seeing him.’3 Johann was just twelve years old when his father died, his only surviving relatives being his sister Ernestine and his stepmother. As Eduard put it, his father ‘had to make his own start from the lowest rung of the ladder’.4 He was fortunate, though, in having a guardian who took good care of him and ensured that he learned a trade. He served an apprenticeship as a bookbinder, working so well that he qualified in less time than usual, on 13 January 1822, two months before his eighteenth birthday. But it is likely that by then he had already decided to make music his profession. By 1825 he was playing the violin and, when required, the viola in the orchestra of his friend – and later rival – Joseph Lanner, and would have liked to branch out on his own.5 He made plans to go to Graz, but by this time Anna Maria Streim, the daughter of the landlord of an inn near one of the venues where it is likely that Strauss played, had informed him that she was expecting a child by him. Her father and Strauss’s guardian made sure that the young man stayed in Vienna and married her, and that he took up the respectable profession of a music teacher to provide for his family. It was not until the spring of 1827 that Johann Strauss could at last found his own orchestra and begin his musical career in earnest.

The child born to the young couple on 25 October 1825 was to become the most famous of all the Strausses. He was christened Johann Baptist Strauss, just as his father had been. A second son, Josef, was born in 1827. During these years the family moved several times, living first in the suburbs to the west of the city centre and then returning to the Leopoldstadt district, where two daughters were born, Anna in 1829 and Therese in 1831. The reason for the move was probably not to get back to the part of Vienna where the family had its roots but to be near to the fashionable Sperl establishment, where Johann Strauss had been appointed director of music in 1829; in fact the family’s first apartment in the district was in a house owned by its proprietor, Johann Georg Scherzer. Together, Strauss and Scherzer made Sperl, a veritable pleasure palace of restaurants, ballrooms and gardens, a byword for what over the next few years people not just in Austria but throughout Europe came to regard as the typical atmosphere of Vienna, its music and its way of life. As Johann Strauss’s fame grew and spread, he had in effect to set up a family business to ensure that his music was produced and his orchestra organised and marketed in the best possible way. The firm needed suitable headquarters, and by 1834 these had been set up on the first floor of a large apartment house in the heart of Leopoldstadt, just around the corner from Sperl.

When Eduard Strauss was born his father was thus an established musician and a well-known personality in Vienna, but the months before his birth were a turbulent and not particularly happy time for Johann and Anna Strauss. Their fifth child, Ferdinand, who was born in January 1834, was a frail and sickly infant; he died in the November of that year. A few days earlier Johann had left Vienna for Berlin. This tour of Germany, which also took him and his orchestra to Dresden and Leipzig, was the first time Strauss had performed outside the Austrian Empire, and it laid the foundation of his international fame. A year earlier he had made his very first concert tour, down the Danube to Budapest in Hungary. He made just two appearances there, playing at two specially organized balls, but the visit was a triumph for Strauss, then twenty-nine years old, and this may have prompted him to think about venturing further afield. Although he had dedicated a waltz he composed earlier in the year to Crown Princess Elisabeth Luise of Prussia, which suggests that Strauss was already interested in establishing contacts with Berlin, this second tour seems to have been begun rather precipitously. Curiously, he had also been in trouble with the police in Vienna, and eventually had to pay a hefty fine for illegal gambling in a room in Sperl as well as for setting off fireworks he had placed on a nearby roof. But a more likely reason for his leaving Vienna in a hurry is that, just as before his marriage in 1825, he wanted to get away from family problems: after all, in the autumn of 1834 he must have been aware that not only his wife but also his recently acquired mistress was expecting a child by him. He seems to have been in no hurry to let Anna Strauss know how he was getting on in Germany. He did not write to her until 19 November, and when he did, he forgot to include an address where she could contact him.6 How she reacted when he returned to Vienna is not documented, but when Johann Strauss gave his first performances there on 14 December, at Dommayer in the afternoon and Sperl in the evening, he was greeted by his Viennese fans more enthusiastically than ever. His next appearance was announced in the Wiener Zeitung for 11 January in Dommayer’s Casino; how much time he spent at home with his family in the Hirschenhaus in the intervening weeks is not known.6

2CHILDHOOD AND EDUCATION(1835–1849)

The Hirschenhaus, the house ‘At the sign of the Golden Stag’, to give its full name, was situated on Taborstrasse, one of the main streets crossing the Leopoldstadt suburb from the Donaukanal, where a bridge linked it to the old city centre of Vienna, towards the main stream of the Danube. The first documentary mention of the building dates from 1650, and it had originally been an inn on a sprawling site with buildings of just one storey. In 1808 two storeys had been added – by ‘a speculative buyer’, Eduard Strauss notes in his memoirs; the Strauss family lived on the first floor.1 Initially renting one four-room apartment, they eventually occupied no fewer than four apartments, each with its own entrance, leading off two staircases. Eduard has left us a carefully labelled plan of the rooms, showing that these included four entrance halls, three kitchens and two rooms for maids.2 In all these accounted for nineteen of the twenty-seven windows facing Taborstrasse and twelve windows at the rear of the house, looking onto the courtyard. This was where the Strauss family lived and worked, and it was the home not only of Johann and Anna Strauss and their five children, but also, over the years, of Anna’s parents and her sister, Josefine, as well as of Johann’s sister, Ernestine, and her husband. Of the three sons, only Johann moved out when he married; both Josef and Eduard brought their wives to the Hirschenhaus and brought up their children there. Josef lived there until his death in 1870, Eduard until he moved out and gave up the apartments in 1886.

The Hirschenhaus, the house where the Strauss family lived from 1833 to 1886 and gradually occupied most of the first floor, seen from Taborstrasse. (Peter Kemp)

From the beginning the Hirschenhaus was the seat of the family business. Johann Strauss had his own apartment with a study that he also used as a bedroom – a practical arrangement in view of his irregular working hours. It was here, Eduard Strauss recalled years later, that ‘my father’s most popular compositions were born, here too was where they were rehearsed and performed for the first time: it was also in my father’s study cum bedroom that the instruments were kept, with only the double basses, trombone and percussion standing in the adjacent room’.3 The fact that the apartment could also be used for rehearsals was important because it meant that new dances could be played without the danger of their being heard by someone who might be tempted to copy them or produce a pirated edition. It also meant that the Hirschenhaus saw a constant stream of visitors. Johann Strauss could only keep his business going with the help of a team of arrangers and copyists, and the passport he was given for his tour of Germany in 1835 lists the names of the members of his orchestra of seventeen musicians.

Eduard Strauss thus grew up in the midst of an extended family, surrounded by music. However, his father thought that music would not provide a suitable career for his sons; it provided, as he knew from his own early experience, a risky and uncertain existence. He encouraged them to choose steady, bourgeois professions. It was not the case, though, that he actively discouraged them from becoming interested in music; this is a point that Eduard Strauss is at pains to stress in his memoirs. He also tells us that his elder brothers, Johann and Josef, both played the piano as children and became particularly good at playing duets together. They were soon much in demand to perform in Vienna’s salons, with Johann always playing the treble part and Josef the bass; in fact in later life they sometimes played together on special occasions, for example for the Prince and Princess of Wales, the future Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, when they visited Vienna in 1868.4 Eduard does not say whether he himself also learned to play the piano as a child, but he does stress that he was an enthusiastic follower of musical life in Vienna from an early age. From a very early age, in fact: he tells us that as a student he did not rest until he had heard all the famous singers of the time, both those who belonged to the ensemble of the Court Opera and those who gave guest performances in Vienna. He gives a list with more than a dozen names, and they include the star Swedish soprano Jenny Lind, who gave her only performances in Vienna in 1846 and 1847, arriving when Eduard Strauss was just twelve years old. He also mentions the music festivals given by the Society of the Friends of Music in Vienna in the 1830s and 1840s; these took place in the Winter Riding School in the Hofburg, the Imperial Palace.5 They offered performances of oratorios on a grand scale; the last of them, with Mendelssohn conducting more than a thousand musicians and singers in two performances of his Elijah, took place in 1847.

Eduard Strauss remembered the 1840s as a golden age in the musical life of Vienna. After all, this was the decade that saw the founding of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and its first concerts, conducted by Otto Nicolai. But it was also a time of growing economic hardship and social unrest, and these developments culminated in the revolution of 1848. These were also difficult years for the Strauss family. Between 1835 and 1844 Johann Strauss had at least seven children by his mistress, Emilie Trambusch. The growing rift between Johann and Anna eventually led to divorce and to Johann leaving the family home in the Hirschenhaus; in 1846 he moved into a separate apartment in Lilienbrunngasse. This was just around the corner and actually still part of the Hirschenhaus premises, but at some time in the following three years Strauss moved to the apartment in the city centre where Emilie Trambusch lived with their children.6

In the course of the divorce proceedings Johann Strauss tried to get guardianship of Eduard and to have him educated at a boarding school. Anna Strauss, however, fought tooth and nail for her rights and to keep the family together.7 She also had to make sure that she and her five children had sufficient income; the need for this was certainly one reason why she was determined that her eldest son, Johann, should be trained as a musician and make his performing debut as soon as possible. He could exploit the name Strauss; Anna could in a way exact revenge on her errant husband by making their eldest son his rival. It was in fact a favourable moment to try to do this: in April 1843 Joseph Lanner, Johann Strauss’s most talented and most popular rival, died unexpectedly, aged just forty-two. In the following months Anna made sure that her eldest son acquired all the qualifications and permits needed to perform in public with his own orchestra. On the evening of 15 October 1844 Johann Strauss junior made his debut, at Dommayer’s Casino in Hietzing, one of his father’s regular venues. It was an event that naturally attracted a great deal of attention in Vienna, and its impact was summed up by one journalist in the subsequently much quoted comment, ‘Goodnight, Lanner! Good evening, Strauss father! Good morning, Strauss son!’8

Johann Strauss junior made his début with his own orchestra just ten days before his nineteenth birthday. At the time Eduard Strauss was nine years old, and he has left no account of how he reacted to this event. There is also no record of his early education; it seems likely, though, that he went to the same elementary school as elder brother Josef, one of whose reports has been found, showing that he attended the parish school of St. Johann Nepomuk just off Praterstrasse, only a few minutes’ walk away from the Hirschenhaus. He then went on, like brothers Johann and Josef, to receive tuition as a private pupil so that he could take the examination to qualify for admission to a grammar school at St Anna’s Upper Elementary School in the city centre near St Stephen’s Cathedral. Johann and Josef had gone on to attend the grammar school run by the Benedictine monks of the Schottenstift monastery, a natural step since the school had also been attached to St Anna’s until the beginning of the nineteenth century. Eduard, however, attended another old established grammar school in the centre of Vienna, the Akademisches Gymnasium, which had been founded by the Jesuits in 1552. In the nineteenth century it was run by the Piarist order, but with lay teachers. The school was affiliated to the university, and so it was to the university chest that the tuition fee of 12 gulden was paid for Eduard’s first school year there – the receipt still shows him as a ‘private’ external pupil. In his second year he submitted an application for the fees to be waived (perhaps because of the parlous state of the family finances with Johann junior away on tour in the Balkans and Johann senior living with his mistress); it was granted for as long as he continued ‘to attend a public school and show himself worthy of this preferential treatment by virtue of diligence, good behaviour and appropriate progress in his studies’.9

Eduard Strauss entered the Akademisches Gymnasium in 1846; it was the school that Franz Schubert had attended nearly forty years earlier. It was situated in the old university quarter, and that may have been one reason why, when the revolution of 1848 broke out in Vienna, Eduard Strauss thought of himself as a student, even though he had only just turned thirteen. In his memoirs he gives a detailed account of some of his experiences during that year, and one of his first memories is that he sported the cap of the student fraternities, placing the black, red and gold of the German nationalist democrats around it and wearing a sash of the same colours. His elder brothers both joined the revolutionary National Guard. Johann became the bandmaster of its Leopoldstadt company; he had, though, to do some soldierly drill first, and apparently was not very skilful at carrying his rifle when marching. In August, on the day of the so-called Battle of the Prater, he found himself on sentry duty in the square beside the Hirschenhaus while his comrades moved off to quell a workers’ riot. Fearing the rioters might find him alone, he placed his rifle in the sentry box and, taking the sheath of his bayonet and box of cartridges with him, quietly withdrew to the safety of the family apartment. That, at least, is the story Eduard tells in his memoirs, and it makes his eldest brother appear like a character from an operetta. But then the dramatist Franz Grillparzer, recalling the events of the spring of 1848, commented that ‘it was the merriest revolution that one could imagine’.10

In the autumn events became decidedly unpleasant. On 6 October, groups of students and workers attempted to prevent the departure of a unit of imperial troops ordered to suppress the uprising in Hungary. While Josef was a member of the Academic Legion of the National Guard, and was thus in action with his fellow students, Eduard, accompanied by Johann’s servant, set off to get a closer view of what was happening. Moving along Taborstrasse towards the main stream of the Danube, they soon found that the street had been torn up to prevent or at least hamper the passage of cavalry and artillery. In order to get any further, they had to cross a side arm of the Danube by crawling across a sluicegate on all fours, joining up with national guardsmen who were finding it difficult to do this while carrying their rifles. When they arrived at the bridge across the main stream of the Danube, Eduard saw how a master tailor, a well-known Leopoldstadt businessman but also a fervent supporter of the revolution, managed to get hold of four cannons by bribing the troops in charge of them. However, when the national guardsmen, with the help of workers and young Eduard Strauss, tried to move them away, they came under fire from the battalion of imperial troops. Three of the cannons were later triumphantly displayed in the centre of Vienna, but Eduard and his unarmed companions had to beat a hasty retreat; he escaped safely, but some of his companions did not. In all it was, as another eye-witness put it, a terrible day.11

But there was worse to come. A few days later two imperial generals, Prince Windisch-Graetz and Count Jellacic, having brutally crushed uprisings in Prague and Budapest respectively, moved on Vienna with their troops. On 26 October the battle for Vienna began, with the city being heavily bombarded. The Leopoldstadt suburb was particularly hard hit. Along with around 1,000 of the district’s citizens, the Strauss family were given shelter in the monastery of the Brothers Hospitallers of St John of God, just across Taborstrasse from the Hirschenhaus. While he was there, the thirteen-year-old Eduard Strauss assisted the head of the hospital attached to the monastery with examinations of the bodies of people killed during the bombardment. It was particularly severe in the night of 29 to 30 October, and in his memoirs Strauss recalls that the resulting fires lit up the sky so brightly that from the mattress he was lying on in one of the monastery’s rooms he could clearly see the time shown by the clock on the adjacent church tower. Among the buildings in the Leopoldstadt suburb that were destroyed was the Odeon, an establishment where both Johann Strausses, father and son, had played. It had been open for less than four years and was home to the largest dance hall in Vienna, where three bands could play at the same time. According to Eduard Strauss, the building had been deliberately targeted because in the months before it had often been used by the revolutionaries for their meetings.

In the aftermath of the bombardments the invading troops seem to have plundered at will. It was therefore understandable that on 1 November Anna Strauss should have returned to the apartments in the Hirschenhaus to make sure that the family’s property was still there. It was, however, a highly risky undertaking, since there were also reports of acts of violence, with the troops maltreating or even killing prisoners and civilians. And according to Eduard Strauss, his mother did indeed have a lucky escape. No sooner had she entered the apartment than the maid came running towards her, screaming. She was being pursued by a corporal and four soldiers who were looking for students. They started to search the house, but Anna was able to get rid of them by bribing the corporal. This was just as well; although neither Johann nor Josef was there, their rifles had been hidden behind a cupboard and Josef’s uniform placed in a chimney.

In the months after the revolution in Vienna had been crushed public and cultural life was at a low ebb. Both Johann senior and junior were badly affected; in 1849 the former made two tours, first to Bohemia and Moravia and then to England, where he spent around four months. Some two months after his return to Vienna, Johann senior fell seriously ill with scarlet fever, contracted from one of his children by Emilie Trambusch, with whom he was now living. His condition deteriorated rapidly and he died in the early hours of 25 September 1849. By this time he was no longer keeping in touch with the family in the Hirschenhaus, so they were only informed some hours later. Anna Strauss immediately took charge – as she was entitled to do under Catholic law, sending Josef to the apartment where his father had died and making arrangements for the funeral. Rumours were also spread that Josef had found his father lying on wooden slats taken from his bed, which, along with all other goods and chattels, had already been removed. Eduard Strauss repeated the story when he wrote his memoirs more than fifty years later – even including the detail that the ‘girlfriend’, as he refers to Emilie Trambusch, had removed the lanterns on his father’s grave in order to have them melted down for their value as metal.12 However, the detailed inventory of the contents of the apartment made a week later shows that the whole story could not have been true. What was true was that his father had left a will leaving most of his assets to Emilie Trambusch and his children by her, while Anna Strauss and her children were to receive only the statutory share required under Austrian law. Needless to say, she was not prepared to accept this, and the matter kept the lawyers busy for several years.

Eduard Strauss does not tell us how he reacted to his father’s death. Throughout his memoirs, however, he is at pains to show his father in the best possible light, whether as a musician or as a father. In the file on his father’s death in the municipal archives his elder brothers, while still legally minors, have their occupations recorded as bandmaster for Johann and architect for Josef.13 In 1849 Eduard himself was fourteen years old and starting his fourth year at grammar school; what plans did he have for his own career?

3MUSICAL DÉBUT(1850–1862)

Throughout his life Eduard Strauss stressed the importance of a good education, and the reports documenting his grammar-school career show that to begin with he was indeed a diligent pupil; however, his performance did fall off in his last two years at school, with his overall assessment dropping from ‘first class’ to ‘second class’ – and at the end of his fifth year he was placed just thirty-first in a class of thirty-three pupils.1 The curriculum for which he studied included Religious Knowledge, Latin, Greek, German, History, Geography, Mathematics and the Natural Sciences, that is to say a range of subjects typical of a nineteenth-century grammar school and also one which, according to some of his statements later in life, would have been an ideal preparation for him to enter the priesthood. That young Strauss should have been attracted to such a vocation is understandable: the apartment in the Hirschenhaus may have been the centre of the family’s musical activities, but as soon as Eduard looked out of its windows he would have seen the parish church of St Josef to the left and the church and monastery of the Brothers Hospitallers of St John of God to the right, where, he said, he spent much time as a boy. In view of the strained situation in the Strauss family while he was growing up, with his father absent for long periods and spending more and more time with Emilie Trambusch and his children by her, and his mother wanting to get a divorce, Eduard may well have found that the religious environment provided some serenity and solace. There is a Catholic tradition that the youngest son of a family should enter the Church, and on one occasion Eduard said that that was indeed what his father had wanted him to do. However, on another occasion he said that his family had been opposed to him taking holy orders and on yet another that he had decided for himself that he would not make a good priest.2 Whatever the truth may have been, there are many indications that Eduard Strauss was a sincerely religious person: he seems, for example, to have disapproved of his eldest brother Johann divorcing and remarrying in the 1880s, while for many years he supported various Catholic events and organisations, for example the Catholic School Society, of which he was an honorary member, performing with the Strauss Orchestra at their twice yearly festive assemblies.

Attached to the monastery of the Brothers Hospitallers there was a hospital with a pharmacy, and these also attracted the interest of young Eduard Strauss. In his memoirs he says that as a schoolboy he would spend his afternoons in chemistry laboratories and hospital wards. Visits to the collection of anatomical preparations of the University of Vienna, at that time being expanded and reorganised along modern scientific lines by the famous anatomist Josef Hyrtl, were also one of his favourite pastimes. In 1853 he made a point of being present at the opening of an ancient Egyptian sarcophagus containing a mummified body. To judge from the detailed account of the event which Eduard wrote more than fifty years later, it was an experience which clearly impressed him;3 curiously, the venue was the Sophienbad hall, where the Strauss Orchestra frequently performed. In view of such interests, the story that, on leaving school, Eduard spent some time working in the pharmacy of the Brothers Hospitallers, may not be a complete invention.4 Certainly throughout his later life his letters and also his memoirs reveal a great interest in medical matters. This often develops into an exaggerated concern with his own health verging on hypochondria, but the fact that Eduard so often stresses his interest in diseases and corpses may also represent a conscious attempt to differentiate himself from his eldest brother Johann, who displayed and perhaps deliberately cultivated an almost neurotic fear of illness and death.