0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

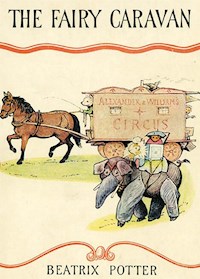

"The Fairy Caravan" is the story of a miniature circus, William and Alexander's Travelling Circus. It is no ordinary circus, for Alexander is a highland terrier and William is Pony Billy who draws the caravan. Beatrix Potter wrote this chapter book for older children towards the end of her writing career. She wrote it for her own pleasure and at the request of friends in America who shared her love of the Lake District and north country tales.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

FAIRY CARAVAN

by BEATRIX POTTER

First published in 1929

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Louisa Pussycat Sleeps Late

TheFairy Caravan

by

BEATRIX POTTER

Author of “THE TALE OF PETER RABBIT,” ETC.

PREFACE

Through many changing seasons these tales have walked and talked with me. They were not meant for printing; I have left them in the homely idiom of our old north country speech. I send them on the insistence of friends beyond the sea.

BEATRIX POTTER.

CONTENTS

[Pg 9]

THE FAIRY CARAVAN

CHAPTER I

Top

In the Land of Green Ginger there is a town called Marmalade, which is inhabited exclusively by guinea-pigs. They are of all colours, and of two sorts. The common, or garden, guinea-pigs are the most numerous. They have short hair, and they run errands and twitter. The guinea-pigs of the other variety are called Abyssinian Cavies. They have long hair and side whiskers, and they walk upon their toes.

[Pg 10]The common guinea-pigs admire and envy the hair of the Abyssinian Cavies; they would give anything to be able to make their own short hair grow long. So there was excitement and twittering amongst the short-haired guinea-pigs when Messrs. Ratton and Scratch, Hair Specialists, sent out hundreds of advertisements by post, describing their new elixir.

The Abyssinian Cavies who required no hair stimulant were affronted by the advertisements. They found the twitterings tiresome.

During the night between March 31st and April 1st, Messrs. Ratton and Scratch arrived in Marmalade. They placarded the walls of the town with posters; and they set up a booth in the market place. Next morning quantities of elegantly stoppered bottles were displayed upon the booth. The rats stood in front of the booth, and distributed handbills describing the wonderful effects of their new quintessence. “Come buy, come buy, come buy! Buy a bottleful and try it on a door-knob! We guarantee that it will grow a crop of onions!” shouted Messrs. Ratton and Scratch. Crowds of short-haired guinea-pigs swarmed around the booth.[Pg 11]

[Pg 12]The Abyssinian Cavies sniffed, and passed by upon their toes. They remarked that Mr. Ratton was slightly bald. The short-haired guinea-pigs continued to crowd around, twittering and asking questions; but they hesitated to buy. The price of a very small bottle holding only two thimblefuls was ten peppercorns.

And besides this high charge there was an uncomfortable doubt as to what the stuff was made of. The Abyssinian Cavies spread ill-natured reports that it was manufactured from slugs. Mr. Scratch emphatically contradicted this slander; he asserted that it was distilled from the purest Arabian moonshine; “And Arabia is quite close to Abyssinia,” said Mr. Scratch with a wink, pointing to a particularly long-haired Abyssinian Cavy. “Come buy a sample bottle can't you! Listen to these testimonials from our grateful customers,” said Mr. Ratton. He proceeded to read aloud a number of letters. But he did not specifically deny a rumour that got about; about a certain notorious nobleman, a much married nobleman, who had bought a large bottle of the quintessence by persuasion of the first of his eight wives. This nobleman—so the story[Pg 13] ran—had used the hair stimulant with remarkable results. He had grown a magnificent beard. But the beard was blue. Which may be fashionable in Arabia; but the short-haired guinea-pigs were dubious. Messrs. Ratton and Scratch shouted themselves hoarse. “Come buy a sample bottle half price, and try it for salad dressing! The cucumbers will grow of themselves while you are mixing the hair oil and vinegar! Buy a sample bottle, can't you?” shouted Messrs. Ratton and Scratch. The short-haired guinea-pigs determined to purchase one bottle of the smallest size, to be tried upon Tuppenny.

Tuppenny was a short-haired guinea-pig of dilapidated appearance. He suffered from toothache and chilblains; and he had never had much hair, not even of the shortest. It was thin and patchy. Whether this was the result of chilblains or of ill-treatment is uncertain. He was an object, whatever the cause. Obviously he was a suitable subject for experiment. “His appearance can scarcely become worse, provided he does not turn blue,” said his friend Henry P.; “let us subscribe for a small bottle, and apply it as directed.”[Pg 14]

[Pg 15]So Henry P. and nine other guinea-pigs bought a bottle and ran in a twittering crowd towards Tuppenny's house. On the way, they overtook Tuppenny going home. They explained to him that out of sympathy they had subscribed for a bottle of moonshine to cure his toothache and chilblains, and that they would rub it on for him as Mrs. Tuppenny was out.

Tuppenny was too depressed to argue; he allowed himself to be led away. Henry P. and the nine other guinea-pigs poured the whole bottleful over Tuppenny, and put him to bed. They wore gloves themselves while applying the quintessence. Tuppenny was quite willing to go to bed; he felt chilly and damp.

Presently Mrs. Tuppenny came in; she complained about the sheets. Henry P. and the other guinea-pigs went away. After tea they returned at 5.30. Mrs. Tuppenny said nothing had happened.

The short-haired guinea-pigs took a walk; they looked in again at 6. Mrs. Tuppenny was abusive. She said there was no change. At 6.30 they called again to inquire. Mrs. Tuppenny[Pg 16] was still more abusive. She said Tuppenny was very hot. Next time they came she said the patient was in a fever, and felt as if he were growing a tail. She slammed the door in their faces and said she would not open it again for anybody.

Henry P. and the other guinea-pigs were perturbed. They betook themselves to the market place, where Messrs. Ratton and Scratch were still trying to sell bottles by lamplight, and they asked anxiously whether there was any risk of tails growing? Mr. Scratch burst into ribald laughter; and Mr. Ratton said—“No sort of tail except pigtails on the head!”

During the night Messrs. Ratton and Scratch packed up their booth and departed from the town of Marmalade.

[Pg 17]

Next morning at daybreak a crowd of guinea-pigs collected on Tuppenny's doorstep. More and more arrived until Mrs. Tuppenny came out with a scrubbing brush and a pail of water. In reply to inquiries from a respectful distance, she said that Tuppenny had had a disturbed night. Further she would not say, except that he was unable to keep on his nightcap. No more could be ascertained, until, providentially, Mrs. Tuppenny discovered that she had nothing for breakfast. She went out to buy a carrot.

Henry P. and a crowd of other guinea-pigs swarmed into the house, as soon as she was round the corner of the street. They found[Pg 18] Tuppenny out of bed, sitting on a chair, looking frightened. At least, presumably it was Tuppenny, but he looked different. His hair was over his ears and nose. And that was not all; for whilst they were talking to him, his hair grew down onto his empty plate. It grew something alarming. It was quite nice hair and the proper colour; but Tuppenny said he felt funny; sore all over, as if his hair were being brushed back to front: and prickly and hot, like needles and pins; and altogether uncomfortable.

And well he might! His hair—it grew, and it grew, and it grew; faster and faster and nobody knew how to stop it! Messrs. Ratton and Scratch had gone away and left no address. If they possessed an antidote there was no way of obtaining it. All day that day, and for several days—still the hair kept growing. Mrs. Tuppenny cut it, and cut it, and stuffed pin-cushions with it, and pillow cases and bolsters; but as fast as she cut it—it grew again. When Tuppenny went out he tumbled over it; and the rude little guinea-pig boys ran after him, shouting “Old Whiskers!” His life became a burden.[Pg 19]

[Pg 20]Then Mrs. Tuppenny began to pull it out. The effect of the quintessence was beginning to wear off, if only she would have exercised a little patience; but she was tired of cutting; so she pulled. She pulled so painfully and shamelessly that Tuppenny could not stand it. He determined to run away—away from the hair pulling and the chilblains and the long-haired and the short-haired guinea-pigs, away and away, so far away that he would never come back.

So that is how it happened that Tuppenny left his home in the town of Marmalade, and wandered into the world alone.

[Pg 21]

CHAPTER II

Top

In after years Tuppenny never had any clear recollection of his adventures while he was running away. It was like a bad mixed up dream that changes into morning sunshine and is forgotten. A long, long journey: noisy, jolting, terrifying; too frightened and helpless to understand anything that happened before the journey's end. The first thing that he remembered was a country lane, a steep winding lane always climbing up hill. Tuppenny ran and ran, splashing through the puddles with little bare feet. The wind blew cold against him; he[Pg 22] wrapped his hands in his mop of hair, glad to feel its pleasant warmth over his ears and nose. It had stopped growing, and his chilblains had disappeared. Tuppenny felt like a new guinea-pig. For the first time he smelt the air of the hills. What matter if the wind were chilly; it blew from the mountains. The lane led to a wide common, with hillocks and hollows and clumps of bushes. The short cropped turf would soon be gay with wild flowers; even in early April it was sweet. Tuppenny felt as though he could run for miles. But night was coming. The sun was going down in a frosty orange sunset behind purple clouds—was it clouds, or was it the hills? He looked for shelter, and saw smoke rising behind some tall savin bushes.

Tuppenny advanced cautiously, and discovered a curious little encampment. There were two vehicles, unharnessed; a small shaggy pony was grazing nearby. One was a two-wheeled cart, with a tilt, or hood, made of canvas stretched over hoops. The other was a tiny four-wheeled caravan. It was painted yellow picked out with red. Upon the sides were these words in capital letters—“ALEXANDER AND WILLIAM'S CIRCUS.”[Pg 23]

[Pg 24]

Upon another board was printed—The Pigmy Elephant! The Learned Pig! The Fat Dormouse of Salisbury! Live Polecats and Weasels!

The caravan had windows with muslin curtains, just like a house. There were outside steps up to the back door, and a chimney on the roof. A canvas screen fastened to light posts sheltered the encampment from the wind. The smoke which Tuppenny had seen did not come from the chimney; there was a cheerful fire of sticks burning on the ground in the midst of the camp.

Several animals sat beside it, or busied themselves with cooking. One of them was a white West Highland terrier. When he noticed Tuppenny he commenced to bark. The pony stopped grazing, and looked round. A bird, who had been running up and down on the grass, flew up to the roof of the caravan.

The little dog came forward barking. Tuppenny turned and fled. He heard yap! yap! yap! and grunt, grunt, grunt! and pattering feet behind him. He tripped over his hair, and fell in a twittering heap.

[Pg 25]A cold nose and a warm tongue examined Tuppenny and turned him over. He gazed up in terror at the little dog and a small black pig, who were sniffing all over him. “What? what? what? Whatever sort of animal is it, Sandy?” “Never saw the like! it seems to be all hair! What do you call yourself, fuzzy wig?” “P-p-please sir, I'm not a fuzzy wig, a fuzzy pig, a please sir I'm a guinea-pig.” “What, what? a pig? Where's your tail?” said the little black pig. “Please Sir, no tail, I never had—no guinea-pig—no tail—no guinea-pigs have tails,” twittered Tuppenny in great alarm. “What? what? no tails? I had an uncle with no tail, but that was accidental. Carry him to the fire, Sandy; he is cold and wet.”

Sandy lifted Tuppenny delicately by the scruff of the neck; he held his own head high and curled his tail over his back, to avoid treading on Tuppenny's hair. Paddy Pig scampered in front; “What! what! we've found a new long-haired animal! Put more sticks on the fire Jenny Ferret! Set him down beside the dormouse, Sandy; let him warm his toes.”

[Pg 26]The person addressed as Jane Ferret was an oldish person, about twelve inches high when she stood upright. She wore a cap, a brown stuff dress, and always a small crochet cross-over. She filled up the teapot from a kettle on the fire, and gave Tuppenny a mug of hot balm tea and a baked apple. He was much comforted by the warmth of the fire, and by their kindness. In reply to questions he said his name was “Tuppenny”; but he seemed to have forgotten where he came from. Only he remembered vaguely that his hair had been a grievance.

The circus company admired it prodigiously. “It is truly mar-veel-ious,” said the Dormouse stretching out a small pink hand, and touching a damp draggled tress. “Do you use hairpins?” “I'm afraid, I'm sorry, I haven't any,” twittered Tuppenny apologetically. “Let hairpins be provided—hair—pins,” said the Dormouse, falling fast asleep. “I will go fetch some in the morning if you will lend me your purse,” said Iky Shepster the starling, who was pecking a hole in the turf to hide something. “You will do nothing of the sort. Bring me my teaspoon, please,” said Jenny Ferret. The starling chittered and laughed, and[Pg 27] flew to the top of the caravan where he roosted at night.