8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

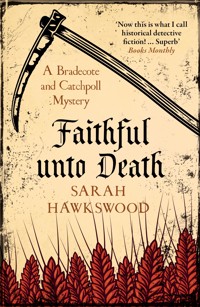

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Bradecote & Catchpoll

- Sprache: Englisch

Bradecote and Catchpoll discover that sometimes the difference between the law and justice is a great one. June, 1144. The naked corpse of an unknown man is discovered near Worcester, while the Prince of Powys's messenger has gone missing. Making the connection, Undersheriff Hugh Bradecote, Serjeant Catchpoll and young apprentice Walkelin head to Wales to discover his identity. But did the dead man deserve a noose rather than a dagger? Retracing the dead man's steps leads the trio to a manor with a difficult lord, a neglected wife, a bitter mother and a fevered brother, none of whom want the truth exposed.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 384

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Faithful unto Death

A Bradecote and Catchpoll Mystery

SARAH HAWKSWOOD

For H. J. B.

Contents

Chapter One

June 1144

Edwin relaxed. In the cool of the summer evening, he had enjoyed a tryst with his cousin from the next village. Haymaking would start on the morrow, and there would be no spare time for dalliance over the next days. The fallen branch by the edge of the coppice gave enough support for a man to have no cause for worry over his balance when obeying a demand of nature, and nature was certainly being quite vociferous. It was only then, with his braies about his knees, that he saw it, the greyish, pale shape half-concealed by a trail of ivy. A hand was a hand, be it never so dead, and the fingers blackening. He blasphemed, crossed himself, and put too much of his weight upon the branch, so that it creaked ominously. Edwin hauled up his braies, nature’s call forgotten, and let curiosity overcome horror. He took the few steps cautiously, as though the dead flesh might suddenly move and grab at his ankles. His heart was thumping in his chest. He drew back a frond, and there lay the body of a man, birth-bare, the flesh beginning to discolour. The eyes at least were closed, and for that Edwin gave up thanks to heaven, but the corpse was ripening, even in this shaded summer woodland.

‘God have mercy,’ whispered Edwin, and crossed himself again. He was praying for the dead man, but not him alone. This was a man he had never seen before, and if nobody else could vouchsafe his name, there would be a penalty upon the Hundred. A man who died naturally would not be half-concealed in such a place. For a moment he wondered if he might lug the corpse to the Hundred boundary. He had little doubt that is what had happened before. Why otherwise would a man, neither from his village nor its neighbour, be found away from any track or pathway, and robbed of every stitch upon him? The smell, and the thought that the underside of the corpse might be even less pleasant, decided the peasant. He went, with swift footsteps, but a heavy heart, to find Godwin, the village reeve.

Godwin, reeve of Cotheridge, walked the four miles to Worcester at as fair a pace as he might in the early morning sunshine, and went first to his overlord, the Church. The Priory of St Mary held Cotheridge, and his dealings with Father Prior were frequent enough for him not to be overawed. He was also keen to have an ally, and one of greater standing, when he made his bow before the lord Sheriff, William de Beauchamp.

Father Prior’s brows furrowed at the news, but he treated it calmly, with all the gravity one might expect from a cleric. He shook his head over the wickedness and agreed to come straight away before the lord Sheriff.

‘I know that he is at the castle, for I spoke but yesterday with his lady, who had come to offer thanks for the recent recovery of their daughter from an ague. Assuredly, he must be told of this terrible find immediately.’ With which the prior rose, and the pair, with Godwin one step respectfully in the rear, made their way the short distance to the castle and the seat of shrieval authority.

William de Beauchamp received the prior with courtesy and a hint of warmth, which left him when his eyes alighted upon the poor reeve, who wrung his hands as he delivered his tidings.

‘And how far from the Hundred boundary?’

‘No more than fifty paces, my lord, perhaps sixty, and the man was not fat, nor unusually tall. I have no doubt it was left so that the burden would fall upon our Hundred and—’

‘Yes, yes. I am well aware of the “games” played with corpses,’ interjected de Beauchamp, testily. Father Prior winced. ‘At least if it has not been moved … since you found it … it may reveal something of use. I will send out my serjeant,’ the lord Sheriff paused, and smiled to himself, ‘and my lord Bradecote also. I will not have cold murder in my shire that goes ignored. Await them in the bailey.’ He nodded dismissal. Godwin withdrew, but as the prior made to do likewise, de Beauchamp halted him with a hand. ‘If the body is not named and Englishry proven, the Hundred will pay the fine, Father Prior. There is the law, and I will have it upheld.’ He did not add that in uncertain times such as these, a small slice of that fine would not meet the Royal Treasury.

‘I understand, my lord. At least the amercement will fall upon all, and not just Cotheridge. It is a small, but profitable, manor for our House. We will pray that the lord Bradecote and Serjeant Catchpoll are fortunate in their enquiries.’

‘Your prayers will be needed,’ muttered de Beauchamp, as the prior departed, passing Hugh Bradecote in the passage outside the hall. Secular authority acknowledged spiritual.

‘I am sorry, my lord,’ sighed the prior, which left Bradecote wondering. However, as he entered the hall, Catchpoll approached from the other direction and fell into step beside him.

‘Looks like the lord Sheriff does not fancy riding in the heat, my lord.’ He sounded cheerful, although had one heard his string of expletives upon hearing of the reason for the prior’s visit, his true feelings would have been known.

‘What has happened, Catchpoll?’

‘A body, that is what, my lord, on the Bromyard road, or near to it as makes no difference, and not fresh either, as I hear.’

‘No wonder the lord Sheriff has no desire for the ride, then.’ Bradecote wrinkled his nose. ‘Sometimes you wish murder was confined to cold months, assuming, that is, the corpse is not some soul who simply felt ill and expired. At which point we just hope his complaint was not one we might catch.’

‘True enough, my lord, though often enough murder does seem to spread like a plague. Once you see one, it is more likely you will see another, like magpies.’

The two men looked to de Beauchamp, who had a small, grim smile playing about the corners of his mouth.

‘There is a body by the Hundred border, just beyond Cotheridge. Go and see what you can make of it, and if the trail is as cold as the corpse, report back to me.’ He managed to make it sound as if the body had been left to occasion him some minor inconvenience.

‘Yes, my lord. Do we know—’ Bradecote began.

‘We know nothing, and like as not we will still know nothing when you have poked about, but we have to make the attempt. Or rather,’ he shrugged, ‘you will. It is but four miles distant. Take up the village reeve with you as you go, and he will show you the place.’ De Beauchamp brushed away a fly, but Catchpoll felt the gesture was also waving them away. Serjeant and undersheriff bowed and set about obeying their instruction. Catchpoll decided he did not want Godwin the Reeve up behind him, and so they brought Walkelin, the serjeanting apprentice, and made sure his horse was sturdy.

Keen to show that the body was barely within their Hundred, the villagers had not removed it to the church, but had covered it with old sacking, and a villager stood ‘guard’ at a suitable distance upwind. The man made an obeisance that verged upon cringing, as if he expected to be beaten for his pains, and did not look the undersheriff in the face, but gazed at the level of his lordly boots. He said nothing.

‘Was this the man who found the corpse?’ Bradecote looked to the reeve.

‘No, my lord. That was Edwin, but he is working the priory’s land today. This is Ulf. He neither speaks nor hears.’

‘And this was just as it was found? You have not, perhaps, moved it closer to the boundary?’ Bradecote raised an interrogative eyebrow, and looked towards where the ground fell away sharply to the tributary stream of the Teme that marked the Hundred boundary. It cut its way through the high ground in a narrow, vee-shaped ravine. In this summer weather it was barely more than mud with a sluggish trickle of water slipping over it, and where the trackway from Bromyard crossed it the sides were shallower. If the body was over a horse, or on some wagon, there would be no hardship in moving it from one side to the other.

‘Not an inch, my lord,’ declared the reeve, as though such a thought had never entered his virtuous and law-abiding head. ‘All we did was cover him, decent.’

‘Thank you. You and … Ulf may leave us now.’

The reeve had no wish to linger. He had been close to the body once, and once was enough. He took Ulf by the arm, and, bowing deeply, withdrew to where a lad stood with a handcart. Before he had gone a dozen paces, Catchpoll was drawing back the sacks to reveal the body of a man, lying upon his back, naked as Adam before the Fall. He was clean-shaven, with light-brown hair, and a nose broad in nostril and inclined to the aquiline.

‘So all we have is a stripped corpse that could be anyone,’ bemoaned Walkelin.

Bradecote looked at Catchpoll. He knew the serjeant could get more than that from their dead man.

‘Don’t speak foolish.’ The serjeant shook his head. ‘Sometimes I wonder why I spends so much time a-teaching of you, Walkelin.’ He screwed up his eyes and stared at the body. ‘I can do this on my own, and I am sure the lord Bradecote here sees what I does, mostly, but let us get you to add your mite. We have a man, but what sort of man? How did he die?’

‘He was robbed of everything, so he wasn’t a beggar, and he wasn’t tonsured so he was not a holy brother.’

‘Right, and wrong too. I agree he was no monk, but if you wanted a man to remain unknown, you would take everything from him anyway, wouldn’t you? Say “yes, Serjeant”.’

‘Yes, Serjeant,’ mumbled Walkelin.

‘So perhaps he was wealthy and robbed, or perhaps he was just got rid of, quiet like, and has had the Hundreds playing “pass the body” these last days.’

‘The corpse shows that.’ Bradecote phrased it as a fact, but it was half a question.

‘Aye, my lord. He has been dead a while, judging by the smell, and the wild beasts have nosed about him.’ Catchpoll turned the corpse onto its side. The back was dust-dirty, and the flesh scratched in places. ‘He has lain upon his back, else there would be bites here, and whichever Hundred he met his death in, it was not so close by. Tell us why, Walkelin.’

There was a moment of silence, and Bradecote could almost imagine he heard the serjeant’s apprentice thinking.

‘Because of the colour in the face, hands and feet, Serjeant. They’re darker, so he hung over a horse just after he met his death, perhaps even his own.’

‘The heavens be praised, he learns!’ Catchpoll’s smile would have hell-fiends worried. ‘Three Hundreds meet within corpse-moving distance here, but even with a low summer level, I would doubt he was brought across the Teme, and if he was, dragging a man up here would be a labour for two men, and suspicious if seen. He might have been killed elsewhere in this parish, or in Broadwas parish next door, though he might have come further than that, even. You would have to ask why, if that were so. So, “not too far” is my thought.’ Catchpoll paused. ‘But let us go back to who he was. I would say he was what, about thirty, average height, not a peasant, because he was well fed to look at him, and most peasants are thin in the summer before the harvest. It is a time of scarcity and empty bellies. Our man here did not go without.’

‘I see now, Serjeant.’ Walkelin nodded. He looked more closely, ignoring the smell as much as he could. ‘I would say he was used to handling a weapon, or using heavy tools, because his arms are well muscled.’

‘Good lad.’

‘I would say the former, Walkelin,’ added Bradecote. ‘There’s a scar on the leg that came from something sharp, and since he was no peasant, that was not a careless sickle cut. That is what you would get if struck by a man on foot if you were mounted.’

‘I might as well go back to Worcester and sit in an alehouse till the wife has dinner on the table,’ grinned Catchpoll. ‘You’ll be thinking yourselves up to every trick soon enough.’ He stood up, easing his back, and folded his arms. ‘Go on, then, what else?’

‘He was murdered for sure, because, even though you will tell me there are those who would steal from a corpse that died natural and say nothing, Serjeant, he could not have stabbed himself in the back.’ Walkelin brushed the dirt away from a distinct tear in the flesh below the ribs on the back. ‘No dragging across the ground made that.’

‘And there is further proof he was moved. The wound has dry blood about it, but no earth stuck in that blood.’ Bradecote could not quite keep the eagerness from his voice. Catchpoll’s grin lengthened.

‘So what do we do now, Serjeant?’ Walkelin looked at him, rather than the undersheriff.

‘We takes him to the local priest and gets him buried. What we have seen we remember, and if we are fortunate, someone will report a man of his description who has not arrived where he should, be that home or duty. If we is out of luck, he was off to Compostela on pilgrimage and will not be expected home for months.’

‘Which leaves us with two, or possibly three, Hundreds still complaining that the fine, if due, lies not upon them.’ The undersheriff looked glum.

‘Well, I reckon as the lord Sheriff would be happy enough to make the two only pay up, but as like he will divide it between them.’

‘The trouble I see, Catchpoll, is that nobody would be willing to tell us anything in case they bring down the fine upon their own Hundred alone, and are berated by their neighbours for it. It must have seemed a good idea when it was brought into law, but this proof of Englishry is a hindrance to us.’

‘We deals with what we have, my lord, good or bad. It would be easier, aye, if all and sundry were keen to tell us anything out of the ordinary, but that’s as likely as frost in August.’ He pulled at his earlobe, thoughtfully. ‘He would have had a horse, as well as clothes, and a sword, too. I doubt they are buried like the squirrels’ nuts for winter.’

‘And the wound implies he was not on the horse when he died. He might have been dragged off and stabbed in the back, but to me that wound says he was unmounted and taken unawares or distracted.’ Bradecote wanted everything they could to lay before de Beauchamp.

‘Put a wench before a man, and have her ask his aid and flutter her lashes, and a killer could come up behind easy enough, and our man none the wiser.’ Catchpoll shook his head at the folly of his fellows.

‘So, it could well be that more than one person is involved in this death.’ Bradecote sighed.

‘If this man was lordly, he would travel with a servant, at the least. There is no servant now.’ Walkelin aired his thought aloud.

‘And if the killing was several days past, the chances of finding him in our jurisdiction are … non-existent.’ Bradecote rubbed his chin. ‘What we can give the lord Sheriff is about as much use as bellows with a hole in them.’

‘We give what we have. He knows as we do, some crimes remain just crimes where only the Almighty knows the culprit, and the only judgement is His. We asks, mind you, upon the Bromyard road that passes so close, if a man with two horses, one animal better than you would expect for the manner of man, has been seen in the last few days, or one with a burdened beast that ought not to be a pack animal. That might give us the chance to say the direction from which the body came.’ Catchpoll was pragmatic. ‘The two villages neighbouring along the road, and no more, since I still say why would any take a body further?’ He shook his head. ‘In truth, the trail is as cold as our friend here.’

Hugh Bradecote’s lips twitched. It was one of the peculiarities of Catchpoll that he so often referred to the body as ‘our friend’. Sometimes he even talked to them direct, but the answers he got from them were delivered without words.

The little church at Cotheridge was a neat stone building of no great age, and Godwin the Reeve, walking ahead and upwind of the handcart, was eager to tell Hugh Bradecote about its erection. It was clearly a source of village pride. The villagers were out about their labours with the hay being brought in. Father Wulstan, their priest, was sat upon a bench beside the church, taking the warmth of the sun to old bones. He looked up when hailed, and Bradecote thought he had been dozing.

‘Good morrow, Father.’

‘Good morrow, my son.’ The old man lifted a slightly shaky hand in benediction, though the undersheriff was not certain as to whether it was for him or the cloak-covered shape on the handcart. ‘My flock are bringing in the cut hay, but you bring not grass stalks but a man cut down, as I hear.’

‘Indeed, Father.’

‘I did not go to him,’ sighed the priest, softly, ‘for I would have taken young William from the haymaking. He acts as my eyes, you see, for although I am blessed by the Light of God, He has chosen to dim the vision of my eyes. I see shapes against the light, but deliver the sacrament more by touch and sound.’

Bradecote could see now the cloudy whiteness of his eyes, that matched the babe-soft ring of white hair about his pate.

‘The man we bring you, Father, has no name to him, but we adjudge him of some standing, though he has nothing upon him.’

‘God has his name, and how he “stood” in this world has no meaning beyond. Serf or seigneur matters not to the All Highest. He shall be interred with due solemnity and respect, but if you find a name to give him for our prayers, all to the good. Bring him into the church.’

Father Wulstan led them into the cool of the building. The nave was not large, but then nor was the village. The chancel arch was crisply carved, its zigzagging lines brightened with red and ochre. The chancel itself was so small as to be almost homely, and the priest moved within it with complete confidence. Until trestles could be brought, the body was simply laid before the altar upon the old sacking. In the confined space the smell of putrefaction was heightened. The priest appeared not to notice it.

‘I fear his soul departed some days past, Father,’ grunted Catchpoll.

‘No matter. His mortal remains are at least to be interred in consecrated ground, and if he died with his sins still upon him, then we will pray the more assiduously for that soul.’

The shrieval party withdrew to the nave, where the smell was less strong, and the priest intoned prayers for the dead. At their conclusion he came to them.

‘Father, we do not know if this man was a traveller, waylaid upon the road, nor even from which direction he might hail. The reeve here has said he is unknown to the village, but as undersheriff I ask him and you both, are there any of Cotheridge who might be capable of this deed?’

‘None, my lord Undersheriff. I have served this community for the better part of forty years and baptised the majority of my congregation. Man is sinful, and Satan may drag one into the Pit, but to kill a man and steal from his body is not the act of sudden rage or evil. If you had said might any steal an egg or two, or take a roebuck, then honesty would have me say it was possible, but not this crime, not with these folk.’

Godwin the Reeve nodded, his expression solemn.

‘To say none could commit a crime would be foolishness, but I agree with Father Wulstan. No man in this village would kill a man like this, not a cold-blooded crime.’

‘Thank you, both of you. It is not an unexpected answer, but useful, nonetheless. If we discover the man’s identity, you will be told, as will Father Prior in Worcester, where I know prayers will also be offered. We would also know,’ Bradecote continued, ‘if any villager here saw a man upon a horse, and leading another saddled horse, these past few days. We will not go to the fields and interrupt the haymaking, but ask today and send report − whether yea or nay − to the castle.’

The sheriff’s men looked towards altar and corpse, and genuflected, crossing themselves, and then, with a nod to reeve and priest, went out into the warm sunshine and clear air, where the birds had yet a few hours of song within them. They took lungfuls of sweet summer air, mounted their horses, and Bradecote took the road direct towards Worcester, whilst Catchpoll and Walkelin cantered back past the coppice and Hundred boundary, to ask their questions in Broadwas. They rejoined Hugh Bradecote awaiting the ferry across the Severn into Worcester, the tide being too high for fording, and with no positive news.

‘That, I am sorry to say, is all we can tell you, my lord, and how you wish to apportion the murdrum …’ Bradecote left that hanging. He stood, with Catchpoll one pace to his rear, in the castle hall.

‘I see.’ William de Beauchamp leant back, a half-smile upon his face. ‘Which means you think you can take your lady back to Bradecote and see your hay cut.’

‘Well, my lord, we can see no further in this. That is it, unless such a man is reported missing, and even then who killed him is likely to remain hidden.’

‘I hate to disappoint your lady, but she will be going home alone, Bradecote.’

‘She will?’ Bradecote looked startled, and Catchpoll sucked his teeth. Trust de Beauchamp to keep his own counsel until the end.

‘I think so. You see, I have received a message from Robert of Gloucester, shortly after you left. The noble earl wishes to know if I have given hospitality this last week to a messenger from the Prince of Powys. He was expecting one to arrive in Gloucester, and he has failed to do so.’

Catchpoll made an unhappy growling noise and spat into the rushes upon the floor. De Beauchamp’s own inclination was for the Empress not King Stephen, and he was now thus allied with the lady’s bastard brother and chief supporter, Earl Robert of Gloucester, whilst still taking his due for collecting King Stephen’s taxes and administering his laws. The earl’s name was not popular in Worcester. Only five years ago he had come and fired the town because it had been given to Earl Waleran de Meulan, who was then fighting for the King. There had been no deaths, for there was some warning of the catastrophe, and the people of Worcester had taken what mattered most to them in chattels and crowded into the sanctuary of the cathedral as the flames took home and business. The only good thing was that there had been not a breath of wind, and before evening a steady rain fell that limited the damage so that some premises remained and others were not in total ruination. Despite this, many had been forced to take shelter with kin or more fortunate neighbour, and rebuilding had taken some months.

‘You think the dead man was this messenger, my lord?’ Bradecote rubbed his chin. ‘Well, it depends upon what sort of messenger Madog ap Maredudd sent, but if it was a man of status … It would fit, although I would have thought he would have taken the Hereford route rather than coming this side of the Malverns. If we but knew his description …’

‘Which is why I am sending you to find out.’ De Beauchamp noted the increasing unhappiness of his serjeant. ‘And I care not how little you like the Welsh, Catchpoll.’

‘It complicates matters, my lord,’ declared Catchpoll, grimly. ‘We have a dead man, killed for perhaps what he had of value in coin, or what he was, or had done, but this adds the possibility that he was killed for the message itself, and that is politics, my lord.’ He said the word as if it were black witchcraft.

‘True, Catchpoll. But if Earl Robert wants to know what happened to that messenger, I would like to tell him, even if I say he is dead. That knowledge might give him help or hindrance, I know not which, and have meaning to him.’

‘And if the man is proved Welsh, does the murdrum fine stand? He would not be proved English, but he would not be Norman “foreign”.’ Bradecote was thinking of unwilling witnesses.

‘A fine is useful coin in hand, Bradecote.’

‘Indeed, my lord, but witnesses might be more forthcoming without the threat of losing coin from their own hand.’

‘Ah, I see what you mean. Well, I would happily forego it if the crime were thus solved. Yes, encourage tongues with that, on your way back from Mathrafal. You ought to be able to reach the monks at Leominster by tonight if you leave within the hour, and the night thereafter you can take your meat at Bishop’s Castle, or Ludlow if you make slower progress. I will give you a letter for the constables there.’

‘Er, and what about when we get to Mathrafal, my lord? We do not speak Welsh.’

‘What man in his right mind would, barring a Welshman? The prince is bound to have someone who speaks a language you can understand, and at worst Latin. Just be polite, and remember it may be a pisspot of a realm, but he is royalty.’

‘Then should you not g—’ Bradecote saw the sheriff’s lips compress and thought better of the suggestion. ‘Very well, my lord, within the hour. I would have an escort for my lady, though.’

‘One will be provided, I promise you. Now, give her your news, and make your preparations.’

‘I am sorry, Christina.’ Hugh Bradecote took his wife’s hands in his own.

‘I am married to the Undersheriff of the Shire. Such things must be, but have a care, my love, in Wales.’

‘Do not tell me you have a dread of it like Catchpoll?’ He smiled at her.

‘Not a dread, no, but where people can be open with each other and yet closed to you, much that goes on may be hidden, and if this man was killed by one who followed from that court …’

‘I shall have a care, fear not. Now, de Beauchamp has promised me an escort for you back to Bradecote. Take it, and tell Thurstan the Steward that if the weather holds, I want the hay brought in next week.’

‘Yes, my lord.’ She dimpled, and dipped in a curtsey, from which he pulled her up and into his arms.

It could not be said that Mistress Catchpoll was as sanguine, when Catchpoll was gathering spare raiment, and a large oiled cloth.

‘Wales?’ She sounded amazed.

‘Do not you start upon that also. I know, I swore I would never go there, but this is at the lord Sheriff’s command, so I has no choice in it.’

‘Why must all of you go? Why not send just the lord Bradecote?’

‘Why? To watch his back, of course. You cannot trust anything Welsh, the weather, the tongue, nor the princes neither.’

Mistress Catchpoll pursed her lips. Her husband’s vocal and violent objection to Wales had been known to her since before they were wed, but the cause of it had remained secret all these years, and she had no expectation of it being disclosed now. Her advice sounded remarkably like that of the lady Bradecote.

‘Well, have a care. You will need all your wits and more if they say one thing to him, and another to each other.’

‘Aye, but I “translate” faces better than most. Whatever the twisting of the tongue, I will know if they speak God’s good truth or Welsh lies.’

‘Then Godspeed, and mind you do not sleep with wet feet.’

With which prosaic advice, Mistress Catchpoll kissed him upon the cheek, and sent him upon his way.

Chapter Two

Walkelin wore a smile of anticipation for the first five miles, until Catchpoll threatened to wipe it from his visage with the back of his hand. He had never been as far north as Ludlow, which he had heard possessed a fine position and a castle of impressive strength. He thought he had been into Wales, having crossed the Wye as a man-at-arms when William de Beauchamp had visited some kinsman, and there were certainly people there who spoke Welsh, but in truth he was not quite certain whether having a Norman overlord made it England. It felt better to say he had been somewhere ‘different’ though, and his mother had been impressed. Eluned, the servant girl in the castle kitchens, had merely giggled when he told her of his adventure, but that might have been because he was trying to kiss her at the same time.

His companions were not smiling. Hugh Bradecote was trying to work out how to ask questions without upsetting royalty, and Catchpoll was ruminating upon having to cross the border into Wales.

They crossed the Hundred boundary without so much as a glance into the coppice upon their right-hand side. The corpse would be shrouded by now, even if none were available to dig the good earth before eventide, and before the sun was well risen on the morrow the body would be buried. Summer was not a time to leave the dead above ground. Having learnt all that they could from ‘our friend’, his physical remains were of no further use, and were cast from mind. It was one of the things that Catchpoll advised, and both his superior and apprentice had learnt swiftly, ‘for dwelling upon them as we cannot bring back mars thinking how to catch them what did for them’.

‘You realise also we will be too late to eat when we reach Leominster Priory,’ grumbled Catchpoll.

‘Then we pay good coin for bread and ale when we pass through Bromyard.’ Bradecote was not going to let Catchpoll wallow in his morose mood for the entire journey, lest it dull his ‘serjeanting’ senses. ‘All we need is a bed for the night and a break of fast in the morning.’

‘Should we be asking about our dead man along this road, my lord?’ enquired Walkelin.

‘We have little enough to go upon, and if we ask all upon the road, we will not get the bed. Better we ask once we have found out if our victim is this Welsh envoy, when we might have a name, a horse described, and details of his companion, if he had one.’

‘And if he is not?’

‘In truth, we can report to the lord Sheriff, and thence to Earl Robert of Gloucester that it was not a messenger to him, whereupon important people lose interest, and with a crime so old and a nameless corpse, we leave justice to God alone.’ Experience was making a cynic even of Hugh Bradecote, of which Catchpoll approved.

‘But—’

‘If you start a-thinking that every death can be paid for, you will drive yourself mad as a hare in spring, young Walkelin. The lord Undersheriff is right. We do what we can, the best we can, but this crime was mayhap four or five days old when we saw the corpse, and every day after that makes it harder.’

‘But we found who killed the horse dealer of Evesham.’ Walkelin frowned.

‘Aye, we did, and against the odds, in my view, but we got a name and he was not far from home. Since most men know who does for ’em, that was a great help. If this man remains nameless, we have no place to ferret, no kin to gain from his death, or lose by it.’

‘But if he is the Welshman?’ Walkelin now hoped this was the case.

‘He might well have stopped at Leominster Priory himself, of course,’ suggested Catchpoll. ‘Welshmen, of the grander sort, are not so common they would not be noted, and if he stayed the night, they would have spoken with him and known his origin. That would give us a day on which he was alive, and a direction.’

‘Where else would he stay if coming from Mathrafal?’ Bradecote settled his horse, as it shied from a partridge flying up by the trackway. ‘He would either come through Shrewsbury and down to Ludlow, or across as we go, past Bishop’s Castle, and either route brings you to Leominster, if he was found between there and Worcester.’

It was, as Catchpoll had anticipated, after Compline, when the three sheriff’s men rode into Leominster. On a summer eve, when travellers made good use of the day, however, Brother Porter was excused the first night offices, and remained until the sun dipped in the heavens before taking to his cot. For late arrivals, he acted as guest-master, and bade them a cheery welcome, and even, when their rank and role was declared, disappeared to bring them beakers of small beer to slake the dust from their throats. He was round of face and body, and clearly found the world, sinful as it was, a place full of joys.

‘Tell me, good Brother, have you had a Welshman, a man of substance, and probably with at least one retainer, take advantage of your hospitality this last week?’

‘Of a certainty, no, my lord. I see all who come and go, and if I missed the one, then I catch the other. We have had a Flemish wool merchant, some pilgrims upon their way to the shrine of St Oswald at Gloucester, and a widow bringing her son to give to God’s service here. No Welshman, of whatever rank, has entered the enclave.’

There was no reason why the Benedictine should tell them false, but it muddied matters. Of all the resting points along the potential route, this was the one that was common, this was the one where the man must surely have stopped.

‘No sense to it, no sense at all,’ sighed Catchpoll, as he rubbed down his horse in the stable. He would not hear of the lord Bradecote seeing to his own mount, and had designated Walkelin to see the animal fed, watered and stalled, but the undersheriff had remained in the horse-smelling warmth, leaning against a stall post, arms folded.

‘There is nowhere likelier, even if he turned to the Worcester road upon a whim, instead of going down through Hereford, and it is a steady day’s ride to Ludlow, or Bromfield, if you want to conserve your horse, and he would, for it had to get him to Gloucester and back. To go further, well, you would be hard-pressed to reach anywhere else without riding at pace.’

‘Unless he knew a place of old,’ offered Walkelin.

‘But he was Welsh,’ snorted Catchpoll, and sneezed.

‘Even Welshmen may have kindred in England. Look at the castle in Worcester. There is Nesta, the cook’s wife, and Walkelin’s wench.’ Bradecote tried to find a reason.

‘If that is so, we may yet find ourselves upon our return journey stopping every few miles to ask if anyone has Welsh kin. Holy Virgin save us from that.’ With which Catchpoll crossed himself, and then spat into the dusty straw.

Brother Porter made sure that Father Prior knew of his important guests, however transient, and their departure next morning was delayed a little whilst the cleric made a gentle fuss of them, and made much of the new buildings in what was a very young house, an offshoot of Reading.

‘What he hoped for was more than a gift for a night’s lodging,’ remarked Catchpoll, sapiently, as they trotted away.

‘Well, if he thought I was wealthy he was sadly mistaken,’ replied Bradecote, with a wry smile. ‘We had a good harvest last year, and there are no rumbling bellies in Bradecote, or my other holdings, but the surplus was not such that I have bounty to dispense to new laid stone.’

‘Reading cannot be poor, after what the old King did for it, and this daughter house does not look as if it is suffering. Treasuries always wants more treasure, be they royal coffers or the Church, and think everyone else should provide it.’ Catchpoll sniffed.

Walkelin, whose relationship with silver pennies was tenuous, since any time he was paid his mother took the coin from him to keep it ‘safe’ and keep him from ‘alehouses and whores’, had lost interest, and was thinking about their victim.

‘We need to think backwards, or rather forwards.’

‘What?’ Catchpoll cast him a look which questioned his wits.

‘If it was a Welsh envoy, how far could he have got on his first day, assuming he set off in a morning?’

‘Which has itself to be only a good guess,’ Bradecote reminded him, ‘and there is a huge difference between what a man might choose to do, what a man could do, and what he might be asked to do, in a day. Even the weather would affect it, and we had those summer storms scarce over a week back. My steward was worried about the hay.’

‘We have too many unknowns, lad. Give us a few things as fact and we can make good guesses, but at present, you will make your head spin to no good purpose,’ Catchpoll advised.

The day grew hot, and their pace, perforce, slackened. Where there was dappled shade there was some relief, but even there the air was still and heavy, smelling of warm leaf litter, and in the open the sun was merciless. They climbed the hill into Ludlow about noon, and went first to the castle, where, within the cool of thick stone walls, Bradecote made enquiry, in case the Welsh messenger had been foolish enough to come into contact with the King’s supporters there, or had been reported to them. As expected, he learnt nothing, but was offered meat and wine, and it gave them the chance to rest for the noontide hour before pressing on to Bromfield. William de Beauchamp had given them a note of introduction for the castellan of Bishop’s Castle, but both undersheriff and serjeant were already doubting that they could make that far in the conditions.

They reached the priory at Bromfield as the brothers finished None and the guest-master met them, courteous but seeming preoccupied. Bradecote asked after any Welshman who might have passed through about a week gone.

‘We often have those with the Welsh lilt here, but there was a man, of some rank and means, here a week ago.’

‘Can you describe this man, and was he alone?’

‘He was well dressed, about thirty years, light-brown hair, quite a definite nose to him, and he had a servant, small weasel of a man.’

‘Can you fix upon the day he came, Brother?’

‘Oh yes, my lord, for he arrived late on the Feast of St Alban, and stayed the day after also, for his horse needed shoeing, and was spent. He said he had seen the forge at the roadside, but the blacksmith told him he would not shoe a horse so blown for fear it would fall down upon him and he be blamed if it was dead. And the man said that he would not reach his destination for the night after the work was completed so would rest the day here. Brother Porter can confirm all this. I will call him.’

Catchpoll frowned, but said nothing, as a novice was sent to the gate. Brother Porter was the antithesis of his counterpart at Leominster, being a beanpole of a man, with a stoop, and a long, rather disconsolate-looking face. His eyes had a dullness, and his voice was a heavy monotone of miserable disapproval.

‘Yes, the proud Welshman rode in late of an evening a week past, his horse weary, and with a shoe near casting, so he said. His servant’s mount was in a worse condition, and it was no wonder that they remained a second night. I thought the beast might collapse before it reached the stable.’

‘Then it would help us to speak with the smith,’ remarked Bradecote.

‘You will get nothing from him today, my lord.’ The guest-master looked grim, and Bradecote was aware of a feeling of foreboding.

‘He brought in the body of his wife to the church but two hours since and is gone to help dig her grave.’

‘She is to be buried so soon?’ Bradecote could feel Catchpoll as tense as he was himself.

‘Father Prior dare not wait, for the corpse is … she went missing, you see.’

‘When?’ Catchpoll was terse.

‘The day after St Alban’s. She was going to visit her ailing mother but a mile away, and never returned, nor reached it either, as was found. Gyrth has been searching for her all the hours of daylight, and more, since. He found her, half-covered in branches.’

Undersheriff and serjeant exchanged glances.

‘You have sent to Shrewsbury?’

‘Indeed, but I heard from a traveller but yesterday there was some trouble in the north of the shire, near Ellesmere, so …’

‘May we see the body? It is not in our jurisdiction, but at least something may be gained that can be writ down for any who come after to seek truth for her.’ Bradecote added his own question.

‘I will ask Father Prior, my lord, and you will need strong stomachs or weak noses.’

The brother went in search of the Prior Osbert, and returned a few minutes later, accompanied by a small, bird-like cleric and a grey-faced man in his forties; a strong, muscular man but one at the end of his physical and mental strength. His shoulders sagged, his arms hung loosely at his sides and his head looked too heavy to lift. Bradecote wondered how he had the energy to help dig a grave.

‘This is Gyrth the Blacksmith, my lord, and Father Prior, who has given his permission as long as Gyrth agrees.’

The prior inclined his head, but the man barely acknowledged them. His eyes were blank.

‘We would see the body, that it might help discover what happened, and who was involved.’ Bradecote spoke gently to the man, who simply nodded.

The prior and the grieving widower led the way to the church, which had become part of the priory, but of which the western end was still for the use of the parish. They passed into the south transept, for there was a chapel where a body might be kept discreetly. Neither man passed beyond the blankets that had been erected as a swift screen to hide what lay within, although no blanket could contain the smell. The air was heavy with incense and all the sweet herbs they could muster, but death, old death, overpowered everything else. Bradecote had become used to the smell of death in the year since he had assumed the position of undersheriff, but even he felt his gorge threaten to rise. Walkelin choked and turned away. Only Catchpoll remained apparently unaffected. He approached the covered corpse and drew back the sheet. The smell hit them afresh. Bradecote crossed himself, and swallowed hard, trying not to breathe through his nose, but finding the smell caught in his throat anyway.

The body was in a poor state, and blackening. What surprised Bradecote was the age of the woman. He thought, though he could not be certain, she was perhaps no more than late twenties, and he had somehow imagined her older. The priests spoke of ‘the corruption of the body’ but it was unpleasant to stand within feet of it. Catchpoll moved closer than Bradecote could dare, and spoke softly.

‘Poor wench. What happened to you, then?’

He touched the neck. The discolouration would have long ago concealed any marks made before death, but he grunted.

‘She was strangled, choked hard, I would say. The voice box is crushed, and had she been found earlier I would swear there would be black bruises before this black.’

‘I do not understand the gown,’ murmured Bradecote. ‘The bodice and shift are ripped, but the skirts have been cut clean top to bottom with a knife.’

The body had not been stripped, for none wished to deal more than needful with it, and the skirts were gathered over the lower part of the body like a shroud, but one side folded over the other.