8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Bradecote & Catchpoll

- Sprache: Englisch

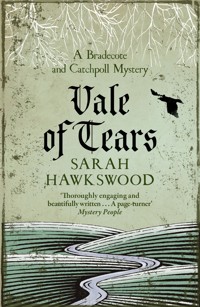

A fast-paced and suspenseful medieaval mystery April, 1144. A body is found floating by Fladbury mill, a man who has been stabbed but not robbed. Undersheriff Hugh Bradecote, Serjeant Catchpoll and their young apprentice Walkelin discover him to be a horse dealer with a beautiful young wife who strays. Did the wife or a lover get rid of him? What link is there to a defrocked monk who was hanged for theft, and where is the horse dealer's steed? The trio must unravel the thread that ties together seemingly disparate deaths before even more people die.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 380

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Vale of Tears

A Bradecote and Catchpoll Mystery

SARAH HAWKSWOOD

For H. J. B.

Contents

Chapter One

April 1144

The rider in the green jerkin knew the way well. He had travelled this route often enough not to admire the spring beauty of the Vale of Evesham, and, on this occasion, to let his mind wander to darker things; to think upon his sister. He shook his head, and his horse snorted as if in agreement with his thoughts.

Poor Edith, dead and buried without even a babe to her name. For all that the family had been proud of her marrying nobility, what good had it done the wench? None that he could see. His brother and their mother had been all in favour of it four years back, and crowed like dunghill cocks at their good fortune. He was only grateful now that Mother had not lived to see her only daughter shrouded and buried. Not that he had seen it either. Her lord was so ashamed of his lowly relatives, though not his wife’s looks or dowry, that he held them at arm’s length even at her death. News had only reached Evesham weeks later, when he had sent his steward with dues for some abbey land, and sent him also to announce her demise. The steward had said his lord grieved mightily, and that was the reason for him not coming in person, but all the lord need have done was send immediately to Evesham and they, her brothers, would have been there at her obsequies. Overwrought by grief? It sounded most unlikely. Her lord had always seemed aloof with her on those rare times Edith had received her relatives.

The man sighed heavily. He was rather more soft-hearted than those to whom he sold horses would ever have imagined. Edith, he thought, had deserved better, and a fine hall and rich hangings did not make up for a cold-hearted husband, and near estrangement from her own kin. How much better it would have been for her to marry Edric Corviser, and live out her days in the happy town bustle within which she had grown up. Perhaps she would have died as soon, but at least not haunted by the constraints of being ‘my lady’, nor of loving a man unworthy of her devotion. He should have listened to her more attentively at their last meeting, assuaged those womanly fears of hers, so that at least she would have departed this life unencumbered by doubts. Poor Edith, foolish Edith. To fall like that, on steps she knew well, must have meant her mind was elsewhere. Perhaps those worries had overset her. In which case, the lordly husband shouldered some blame. Yet, when brother had confronted husband, the man had looked down his noble nose and told his brother-in-law that he was a fool, and an offensive one at that, and if he so much as stepped upon his lands again he would have his men-at-arms teach him a lesson he would not forget and send him back to Evesham with lash marks that all would see. The rider fumed. He would put any profit from his next two sales for the monks at the abbey to say Masses for his sister’s soul, and her hard-hearted lord would live to regret how he had mistreated her, and her folk.

A chaffinch sang lustily on the bough of a crab apple. This first week after Easter 1144 fell at the beginning of April, and the male bird was in full courtship plumage, the slate grey of his head contrasting with the deep, rosy pink of his breast. The blossom was as yet mostly buds, but the first early flowers dared any frost to do its worst upon them. Primroses still adorned bank and spinney, and the green freshness of unfurled leaf and new grass was almost too much to assimilate. The glories of nature passed by at the pace of his trotting horse, whose ears flicked back and forth as a blackbird pinked in a hedgerow. He came shortly to the junction with another track. A rider approached and turned a neatish chestnut cob to take the same route. The rider, who wore his woollen cap at a jaunty angle, and seemed very pleased with the day, nodded in a vaguely amicable way, but said nothing for some time. They passed through the village with its broad greensward in its centre, and continued towards the river. Only as they approached the wooden bridge over the Avon did the happy man attempt to strike up a conversation. He complimented his new-found companion on his handsome horse.

‘Ah, now I can see as you are a man who knows his horseflesh, friend. Well up to your weight, and good haunches to him, has your beast. I’ll vouch he keeps a good pace all day and does not flag. My old fellow is not as impressive-looking, of course, but has stamina, and that counts for a lot, you’ll agree?’

The green-jerkined man nodded in a non-committal way.

‘You’ll be heading up to Stratford, perhaps? I am only going as far as Welford myself.’ The happy man seemed to look forward to the company.

The other rider murmured about heading south into Gloucestershire. This gregarious stranger seemed mightily keen to talk, and clearly took no notice that the responses were brief. He had returned to the subject of the horse again, and was extolling its good points when the cob jibbed suddenly. The man patted its neck placatingly, and heaved a sigh.

‘There, and I hoped the beast would have the sense not to play up with yours beside it.’ The rider shook his head. ‘I do not know why, but he has a dread of crossing water. I end up leading him every time, and cursing him roundly, especially when it means fording, though in all other respects he is a good horse.’ He dismounted, and rubbed the cob’s soft nose affectionately.

In truth, the animal did not look too distressed, but out of courtesy the man in the green jerkin also got off his horse, puffing slightly, for he was round of cheek and belly, and began to lead his own beast. The Avon was visible through the cracks between the boards. It passed beneath them, augmented by spring rains, but flowing clear and steady, with pike lurking in the sluggish margins among the weed and reeds for unwary prey. The horses clattered slowly over the wooden planks as the riders talked, and then, had anyone been looking, something strange happened. The rider of the cob stepped in front of the man in the green jerkin and turned to face him. A moment later the man in the green jerkin sank to his knees, but was hauled upright and tipped into the wet welcome of the river. Without so much as looking over the low rails, the other man mounted the cob, took the riderless horse by the bridle, and trotted back the way he had come.

The undershot wheel turned steadily, relentlessly, unhurried as always, belying the bustle within the mill as the wheat was ground between the great querns, and the flour slid down the chutes to the sacks beneath. Martin, the miller’s son, and Ulf the apprentice, watched them fill and lifted them away before they overflowed. Neither lad numbered more than thirteen years, but the labour gave them muscled arms and shoulders sturdier than their fellows in the village, excepting the blacksmith’s boy. Their faces were dusty white with the flour, and they coughed occasionally. Speech was a waste of breath, and brought only more coughing, so they worked in silence, each waiting eagerly for the cry of the miller above that the last sacks of grain had gone in for the morning’s grinding. Come noon they were able to ease their shoulders, and enjoy the fresh, clear air outside in the sunshine, while they lounged on the grass and took bread for their hunger, and small beer to wet dusty young throats. Then they could break their unwilling silence, and be their age.

They relaxed in the gentle April warmth, though the breeze had a bite to it still, reminding them that this was spring and weeks yet from summer. It was Ulf who first noticed the body in the leat, thankfully before it caught in the wheel. A dead sheep had done so over the winter and been messy enough. He scrambled to his feet, pointing, and sending Martin running for his father and a stout pole. Wulstan the Miller did not doubt the boy, for he was pale, wide-eyed, and gabbling.

‘Nay, slow down, lad, or else I’ll not catch a word.’

‘A body, Father, a body in the leat. Come quick afore it is taken by the wheel.’

‘A beast you mean? A calf or—’

‘A man, honest, a man. Come.’ Martin tugged his father’s sleeve, though the miller needed no prompting.

Ulf had grabbed as large a stick as he could wield, and was trying to delay the progress of the corpse, with a modicum of success, though the force of the water in the narrow leat meant he was struggling. The body floated face down, the arms outstretched, the fingers white and puffy. It had been a man, clearly, and yet it was no longer a man but a grotesque parody of one. Wulstan brought a rake pole that they used to pull clogging weed from the channel, and between the lad and his master, the corpse was prodded into reach. The miller knelt and hauled the waterlogged body from the stream, needing all his considerable strength to pull it clear, and rolled it onto the grass to stare at the sky. Ulf cried out an oath and turned away, retching. The white, oedematous flesh had provided food for fish on its journey down river, and the face was ragged and unsightly. Wulstan crossed himself.

‘God have mercy. Best fetch the reeve, Martin. And Father Jerome.’ He shook his head. ‘It is ill folk will think of me for taking him out, but there was no choice once he was in the leat.’

‘Father?’

‘The Hundred pays a fine for any man dead by violence who is not proved English, son. It is called the murdrum fine, and King William imposed it upon us, lest we kill his men from Normandy. Not that I have seen more than a half-dozen men in my life as I would think foreign by speech or garb. No, these days it is really a tax, and a way to show the lords are “better” folk.’

‘Then cast him into the river proper again, Father, if you doubt he met his death by accident.’

‘Tempting, Martin, but this was a man. How would you feel if your kin were put back, aye, perhaps time and again, and kept from holy ground for the sake of such a risk? No, off you go, and tell nobody else on the way, mind.’

The boy ran, glad not to have to look at the ravaged face any more. He wanted to show he was made of sterner stuff than Ulf, but his gorge had threatened to rise, even so. He did not hear his father address the body, in a hushed whisper.

‘May you have drowned by accident, friend, and God have mercy on both you and us.’

The priest was easy enough to find, but the reeve’s wife could only say he was off with one of the village men, discussing some dispute over an orphaned lamb, and it was some time before Martin and Father Jerome caught up with him. The villager was most unwilling to see the reeve depart before he had made his position abundantly clear, and several times over, and since Martin could not reveal the reason for his urgent need for the reeve at the mill, it was fortunate that the priest was there to add his authority. Only as the three of them made their way along the Avon bank to the mill could the boy tell of what had turned up in the leat that noontide.

Oswin the Reeve looked grave, and even more so when he saw the body. Martin withdrew, having, he felt, been man enough already. Miller, reeve and priest looked down at the remnants of a middle-aged man, well clothed and booted, with a scrip still at his belt, and coin within it, as a brief investigation revealed.

‘The poor man drowned,’ sighed the priest, shaking his head. ‘So many fail to appreciate the river is not to be treated lightly.’

‘Well for sure he was not the victim of a robbery, God be praised,’ averred the reeve. ‘You only have to look at him to see that. If he fell in and drowned, then we might yet avoid the murdrum fine. Yet what worries me is those good clothes. This was no poor man, not by his garb, and the more chance he was not English.’

‘I had no choice, Oswin.’ Wulstan sounded apologetic.

‘No, that I grant you. Pity it is, though. Ah well, I had best head to Worcester in the morning, and report the corpse. Father, he can be kept in the cool of the church, yes?’

‘Of course, though we cannot shroud him until the law has seen him.’ Father Jerome sighed again. ‘We are blessed to be on the fertile edges of the river, but in its floods and what it brings us, we have to pay for that blessing. Have you a hurdle on which he could be carried, or a handcart?’

‘A handcart, yes. And some sacking to cover him decent enough. Wait here, and I will fetch both. Then I suppose we has to wait for the lord Sheriff at Worcester.’

William de Beauchamp, Sheriff of Worcester, had much to occupy him. Lady Day had just passed, and rents and taxes had to be gathered from the tardy and unwilling as the new year commenced. His own manors were in the midst of lambing, and his daughter Maud had been ailing of a fever and given his lady wife sleepless nights of worry, and requests for his immediate presence at Elmley Castle. Beset by myriad calls upon him, he was not a happy man, and when William de Beauchamp was not happy, nor were those who served him.

Serjeant Catchpoll headed the list of unhappy underlings. Since the sheriff of the shire would not go door to door with demands for payments, as usual the task was delegated to the sheriff’s serjeant. He did not like being set to the task with grumbling and curses, and he also disliked hunting down those unwilling, or indeed unable, to pay their dues, and regarded it as unworthy of him. For all that the tax-gathering gave Catchpoll his name, it was real crime that interested him − murders, blackmails and thefts, though the sheriff would have told him that not paying tax was stealing from the King and from him too, since he took his pennyworth of shrieval dues. Catchpoll had, therefore, in his turn, delegated a large part of it, this particular spring, to his ‘serjeanting apprentice’, one flame-headed Walkelin. Trouble was, Walkelin, whilst proving a keen young man, and useful in hunting criminals, had a long way to go in mastering the art of being ‘a right miserable bastard’, which was a prerequisite for acting as the lord Sheriff’s tax gatherer. Catchpoll had tried to teach him to smile in the face of the tales of woe with which he was everywhere presented, and to view with the utmost suspicion the promises to turn up at the castle gates the very next day with the missing monies, but all too often he returned with less than the sum due, and moved to pity by reports of infants who risked starvation, and elderly dames who would be cast into the streets without even a blanket to call their own. Catchpoll shook his head and winced.

‘I cannot decide which is worse, young Walkelin, you being so soft in the heart, or soft in the head. Half Worcester must know by now that they have but to show you a mite with big blue eyes and a trembling lip, and claim they went to bed hungry the last three nights, and you will be waiving their dues.’

‘But what about the Widow Saddler, then, Serjeant? She said as you had turned a blind eye these two springs past to her shortfall. Was she telling untruths?’

‘Ah.’ Catchpoll paused. Widow Saddler had five brats under the age of seven, and her husband’s business had gone to a cousin who considered kinship was all about taking, and nothing to do with giving. She worked hard, plying her neat stitches in bridles as before, but the cousin gave her nothing but a lean-to he rented as part of the property and expected her to stump up the rent money for it. ‘That,’ announced Catchpoll, decisively, ‘is exercising serjeant’s’ − he floundered for the term he wanted − ‘discreet-tion, and only to be used by serjeants with long years of experience. Besides, you’ll find I shake that nithing who runs Aelfraed Saddler’s business for the extra.’

He sent Walkelin back to chasing up the lagging taxpayers with a stiffened resolve.

Oswin, the reeve of Fladbury, reported first, as was right and proper, to his overlord, the Prior of Worcester, since Fladbury was held by the priory. The Benedictine shook his head in sorrow, promised prayers for the dead man, and sent the reeve on to the lord Sheriff.

‘But what of the murdrum fine, Father Prior, if we cannot find a name and prove him English?’

‘We can but pray also that the fine is not levied. It is a grievous burden on the Hundred, for sure. But be positive. Were this man not English, surely he would have been remarked upon if lost? And he drowned, remember. Unless it was proved someone pushed him into the river, drowning is an accident.’

‘I hope so Father Prior, I do heartily. Wulstan had no choice but to take the body from the water, or else it would have been caught in the water wheel and been mangled, as well as perhaps causing damage to the mill.’

‘Oh indeed, he did right. This poor man needs now his name and decent burial with kin to mourn him. But even if that proves impossible, the Good Lord knows him already, and we will pray for his soul as fervently. Now go and inform the lord Sheriff, and hand the business over to the law.’

Oswin went from priory to castle and sought audience of the lord Sheriff. William de Beauchamp was not, however, available, since he was meeting a delegation of the Worcester burgesses, and Oswin had to make do with the sheriff’s serjeant. In truth, he found it far easier dealing with a man of his own rank and language, with whom he could discuss the matter frankly. At the conclusion he was given leave by Catchpoll to return home, with the assurance that the lord Sheriff would be told swiftly of the matter, and that most probably Fladbury would see the sheriff’s men in the next day or so.

It was several hours later that Catchpoll repeated the tale to his superior, who had had an irritating afternoon with the town worthies.

‘A body from the river! Well, like as not it is a drowning from somewhere. Nothing that I need investigate in person.’ He growled, and pursed his lips.

‘But the report said the body was well dressed, in a green jerkin with fine decoration, and good boots too, my lord.’

‘You mean the body might be someone of note?’ De Beauchamp eyed Serjeant Catchpoll with suspicion. ‘If you are trying to worm your way out of a journey to Fladbury, Serjeant, you are out of luck.’

‘Me, my lord? A journey to Fladbury sounds far more interesting than another day making myself the most unpopular man in Worcester, my lord.’

‘I thought you had your man Walkelin doing that, you old fox.’

‘Ah yes, but he is not yet experienced enough to do it alone for long.’

‘And I also thought that at this season it was I who was the most unpopular man in Worcester.’ The sheriff grinned, wryly.

‘The mantle of your unpopularity spreads wide, my lord,’ responded Catchpoll, his lips twitching. He thought he could judge his superior’s mood well enough to jest.

William de Beauchamp laughed out loud.

‘“Mantle of unpopularity”. I like that, Catchpoll. Well, you can creep from under it and head for Fladbury in the morning. And as for the status of the corpse, you can go through Bradecote and tell my undersheriff he can stop tupping that new wife of his and abandon a husband’s duties for shrieval ones. He can inspect the body with you, and take any declarations on identity, noble or otherwise.’

‘And if it is murder, my lord?’

‘You’ll bring me the killer, dead or bound, or have very good reasons why not. I trust you not to fail me, Catchpoll.’

‘Thank you, my lord.’ Catchpoll was in fact less than grateful for the burden laid upon him, but judged that at least if he failed, the undersheriff would share the blame. ‘And Walkelin?’

‘Oh, take him with you. I don’t want a job half-done here, and him maundering about looking lost without your guidance. He shows promise, I give him that, but he has a lot yet to learn.’

Chapter Two

Catchpoll rode into the manor at Bradecote on a loose rein, mid morning on the following day, with Walkelin still chuckling over what the lord Sheriff had said about his newly-wed undersheriff. The serjeant thought Walkelin would do well to be reminded that Hugh Bradecote was not at the top of the chain of command. They got a nod of recognition from the man-at-arms who was honing a knife on a whetstone. Walkelin rather hoped that he would follow Serjeant Catchpoll within, but he was told to walk the horses, since, with luck, the undersheriff would be at home, and they would be able to set off without delay.

Christina Bradecote was sat in the solar, bouncing a gurgling baby of just over seven months on her lap. It was a natural enough scene, and the look of love upon her face would not have been different had she given birth to him. She was his mother now, and if she dreamt of a child of Hugh Bradecote’s getting, stirring within her, she had already given her mother-love to baby Gilbert, and prayed for the soul of the woman that bore him. Ela Bradecote had been cold and still within hours of his birth, God grant her peace. Ela might have carried him, reasoned Christina, but it was she would raise him, Hugh’s son, now ‘their’ son, and his first attempts at speech would be directed at her just as surely as if she had passed through travail with him.

She looked up as Catchpoll was ushered in, and smiled.

‘Serjeant Catchpoll. Ah, do not tell me! You are here to drag my lord from my side, shame on you.’ She pouted, but a dimple peeped. He thought how well she looked, how openly happy. ‘He is gone out with the steward this morning, but I expect him to return by noon.’

‘Sheriff’s business, my lady, so I say as the shame is the lord Sheriff’s.’ Catchpoll gave his death’s head grin. ‘And I will wait in the hall, if I may. No wish to disturb you and the babe.’ He nodded at the infant, who was now blowing bubbles, and still gurgling.

‘He has grown well, since you saw him last, has he not?’ Christina sounded mother-proud.

‘Aye, he has that. And has teeth, I see.’

‘Oh yes, as the wet nurse keeps muttering about.’ She sighed. Nobody knew just how much she regretted that she could not nurse him herself, how strong the urge flooded through her when she cradled him, but instinct was not enough. So, when he clamoured for food, it was Aldith whose scent and succour brought peace to the hall. ‘But wait here, and tell me of anything interesting that has happened in Worcester.’

It was idle enough chatter, but passed the time until the long stride of Hugh Bradecote was heard crossing the hall. He opened the door, and entered, shaking the wet of a sharp April shower from his hair.

‘Catchpoll, you come with orders, no doubt. I saw Walkelin in the bailey, taking shelter from the rain.’ He nodded at the grizzled serjeant, and indicated a seat, then gave his wife a bright, and intimate, smile. If the lady Bradecote looked radiantly happy, her lord looked almost smug. Little over two months after they were wed, the novelty of marriage had clearly not begun to dull into the everyday.

‘My lord, the lord Sheriff has had word from Fladbury of a body fetched up in the mill leat, and the corpse has to be viewed and decided upon. God alone knows where it has come down from, and how many times it has been cast back, quiet like, like a tiddler, by those afraid to be penalised for it, but there.’

‘And the sheriff wants me as well, to look at a drowned body?’ Bradecote looked surprised, and not a little annoyed. Was the sheriff just ‘reminding’ him of his shrieval duties?

‘Oh aye, I thought you’d not be impressed, my lord. But this body is not just some villager who thought he would look at his reflection in the water one night whilst ale-sodden, and tumbled in. This corpse has no name, but he has got a fine set of clothes, according to report. The Hundred is keen to find out who he might be to avoid the murdrum fine, if he is English that is. And if he is a better class of corpse, well, the lord Sheriff thought a better class of sheriff’s man ought to take a look.’ Catchpoll did not grin, quite, but the eyes danced.

‘But even if he isn’t English, a drowning is not always a murder. Accidents happen all the time.’

‘Indeed, my lord, and that is one of the things we are going to look at. Most folk don’t study the dead as we do. They see a body in the water and say “Ah, he drowned”, unless there is an arrow through his neck or his head is missing. And these people want us to say he drowned in an accident. But you and I know a man can drown, or can be drowned, and if there are signs—’

‘So I cannot get out of this, can I?’ Bradecote interrupted, with a groan.

‘No, my lord,’ replied Catchpoll, cheerily.

‘I do not see why you should be dismayed, my lord.’ Christina was trying not to smile at his reluctance. ‘It sounds but a simple task. Go and see this body, decide on how he died, and return home.’

‘And if it was murder after all?’

‘Then you will solve it. I have every faith in you, in you both.’ She beamed at her husband, and then at Catchpoll.

‘Thank you, my lady. The lord Sheriff said much the same, but somehow it sounded more of a command and less of a compliment.’

‘We will eat, and then be about the business. We can reach Fladbury by evening, easily enough. Go and fetch in young Walkelin.’

‘And I will send for food and ale.’ Christina called the nurse, who had been dozing in a corner, to take the baby, and would have followed Catchpoll from the chamber, had not her husband detained her by taking her arm. ‘My lord?’

‘You understand I want to go and to return swiftly?’ He spoke softly.

‘Of course.’ She smiled fondly at his concern, and her voice dropped. ‘I know that you will not be away longer than is needful, but your mind must be upon the task, remember, not wandering back here beneath the bedclothes.’ She blushed, but her eyes were bold. ‘I shall see to it that your manor runs well in your absence, and keep your bed warm ready for your return.’ Her finger stroked down his slightly stubbled cheek and across his lips. ‘Now, my lord, a wife’s duties also include hospitality, so let me go and arrange for bread and a good cheese to set before you, Serjeant Catchpoll, and the ever hungry Walkelin.’

A little over an hour later, Hugh Bradecote mounted his big-boned grey, and with a nod to his lady, led the trio of sheriff’s men out of the courtyard at a brisk trot. He had parted more privately from her with an embrace that was both a farewell and a reminder of his passion for her, and she could watch him depart with what appeared upon the surface as almost regal coolness, however loth she was within to see him leave. He was the undersheriff of Worcester, and duty was duty. It was what had first brought him to her, and she accepted that it would also be what frequently took him away from her. All she asked of heaven was that he always came back.

The sheriff’s men arrived in Fladbury as the afternoon cooled to evening, and went first to the house of Oswin the Reeve. His wife was quite overcome at the presence of the undersheriff in her humble home, and her nerves sought relief in chatter, which was as voluble as it was inconsequential. Bradecote cast the reeve a look which spoke of the need for a simple exchange of information, and so Oswin ushered them, as soon as he could, to the church, wherein the body lay by the font.

‘You need me to remain, my lord?’ He sounded none too willing.

‘I would rather you fetched the priest, and then the miller and his lads that found him, if you would, Master Reeve.’

‘Aye, that would be best. I’ll not be long.’ He eyed the covered body with distaste, and made his escape.

Catchpoll and Bradecote exchanged looks. The undersheriff nodded, and Catchpoll lifted the old blanket that covered the body. They did not expect it to be a pretty sight, but then they had seen bodies before that had not met a peaceful end in their beds. The serjeant sucked his teeth, speculatively.

‘Been in the water some time afore they got him out. Makes things more difficult for us, of course, both to find out what happened and where.’ He pursed his lips. ‘Did you drown, my well-dressed friend?’

Walkelin frowned.

‘If he came from the water, Serjeant …’

‘That just proves where he was, not where he had been, nor yet what happened. You help me get his clothes off him, young Walkelin.’ The younger man pulled a face. ‘No point in being sight-sick, lad. It is just a body.’

‘But it is a bit … ripe, Serjeant.’

‘Then best we do it now, before it gets any worse. Come on.’

They took the garments carefully, piece by piece, and Bradecote inspected them for any signs that might help them. The green jerkin was well made and had intricate stitching. The undershirt was fine linen and his boots were not long worn. The sound of footsteps on the stone flags made them turn. The priest had entered. He looked sombre, and nodded at the undersheriff. Catchpoll resumed his inspection of the naked torso, and screwed up his eyes. The flesh was white and swollen from the water it had taken into the tissues, though where the clothing had covered it there was less disfigurement from fish biting.

‘Go on, Catchpoll, tell me what you think you can see.’ Bradecote studied his serjeant as carefully as the serjeant studied the corpse.

‘Well, if you look careful like, I think you can see a thin mark, just here, up by the rib. There is no sign of blood of course, and the swelling of the flesh makes it hard to see. But I think a narrow blade entered here, a dagger most like. If it was long enough it would kill fast, into the heart.’ Catchpoll pressed his thumbs either side of the faint mark, and the skin did part slightly.

‘Is it enough to prove an unlawful death? It seems such a small wound.’ Father Jerome peered, reluctant but wondering.

‘Size of wound is not everything, Father.’

‘No, but will it be believed?’ Walkelin asked. ‘You said yourself that folk will be wanting death by drowning, since a murder would bring the threat of the murdrum fine.’

‘What they want and what they get is not up to them, or us. It is up to the law. This man died by another’s hand.’ The serjeant was firm.

‘Is it just possible that he could have taken his own life, Catchpoll?’ Bradecote would prefer it not to be a killing but …

‘Well, I doubt a man would stab himself, and right by the river. Most folk that kill themselves want to be found, want to show how they were driven to the deed by circumstance or persons they knew. Remaining unknown is not often their choice. Also, a man might cut his own throat, but this is not a common wound to inflict upon oneself. No, you can be sure this man did not die by his own hand.’

The door of the church creaked open, and the miller, his son and apprentice entered cautiously. The priest instinctively placed himself between them and the pale body, and Hugh Bradecote stepped forward.

‘You called for us?’ Wulstan asked. ‘I am Wulstan, miller of Fladbury, and this is my son, Martin, and my apprentice, Ulf. They first saw the body in the leat.’

The boys nodded.

‘When was this?’ Bradecote smiled reassuringly at the youths.

‘Day before yesterday, about noontide, my lord,’ volunteered Ulf. ‘We only came out of the mill then, to eat. It was in the leat, about a hundred paces from the wheel, floating. When it entered, we could not say.’

‘Understood. Thank you.’

‘My lord, I took him out the water, but I have seen things that have been fresh in and those that have not, and he was not. There is no saying where he comes from, nor if this was his first landfall, if you get me.’ Wulstan was sombre.

‘Unwanted, and thrown back − aye, that is likely,’ muttered Catchpoll.

‘But I did right, to get him out, the drowned man?’ Wulstan needed official commendation. ‘Besides the fact he would have got caught on my wheel.’

‘You did right, but the man did not drown.’

‘But you can see—’

‘We can see that he took a blade beneath the ribs, and he did not get that off some Avon pike.’ Catchpoll saw the anguish on the miller’s face. ‘It is sorry I am for it to be so, but we now have even more reason to seek out his identity, for this man was killed by intent.’

‘You will find out who he is, my lord?’ It was almost a plea. Wulstan was imagining the opprobrium of his neighbours and looked to Hugh Bradecote to rescue him and them from the consequences of his good deed.

‘Oh, I would expect to find out − and think of it, Master Miller. There are far more Englishmen than “foreign” in the shire. Personally, since I was born here, have never left the shores of England, and nor did my father before me, I think of myself as English, whatever the bloodlines may prove.’

‘Fair enough, my lord, but ’tis those bloodlines that count, and for such purposes you are tainted foreign, however much you gainsay it.’

‘There’s no cause to berate the lord Undersheriff.’ Catchpoll was wary of his superior’s dignity, however much in agreement he might be with the man.

‘It is all right, Serjeant. Master Miller was stating a fact, and we deal in facts, as you often tell me. The fact we need next is where this man entered the river, and where he came from before he did so. If he had been in the river some three or four days, how far might he have come?’

‘Avon is flowing nicely, my lord. If he was midstream it might be he came from Warwickshire, easy enough, but then if he got into the shallows for a bit and lingered, so to say, he might only have come from below Evesham, even.’

‘My lord, where he came into the river might be upstream of where he lived anyways,’ announced Walkelin, thoughtfully. ‘We do not know where he was heading.’

‘And we do not know of anyone being cried as missing as yet. That worries me, so it does.’ Catchpoll grimaced. ‘If a man goes off for the day and does not return, his nearest and dearest make a fuss.’

‘Then perhaps he lived alone, or else his “nearest and dearest” did not expect him back for some days, Catchpoll.’

‘Or at all,’ piped up Martin, becoming interested.

‘Or at all, my lad. Well spotted.’ Catchpoll nodded at the boy, approvingly.

‘We can say as he is not from about Fladbury, for anyone that grand would be well known hereabouts.’

‘Which means we look in bigger pools, if he is a bigger fish.’ Bradecote smiled slightly. ‘Such a man as this might not stand out so much in a town, a town like Evesham. Catchpoll, I am sending you across by the nearest ferryman to work up to Evesham on the far bank, and find out if our man was known or fetched up there in the last few days. Walkelin and I will take this bank and we meet in Evesham tomorrow afternoon. Father, I want the body sent to the abbey at Evesham. Can you arrange for a cart or burden-beast to get it there, but not before noon? I would prefer us to be there first and speak to Abbot Reginald.’

‘Of course, my lord.’

‘And for tonight?’ Catchpoll was wondering.

‘I can offer you hospitality, my lord.’ Wulstan offered. ‘The wife would be pleased to feed you, and there is space enough in the mill.’

Bradecote smiled, though his heart sank at the thought of a night upon the mill floor, rather than snuggled up to his warm, soft wife. Mistress Miller also proved to be a cook who believed in quantity rather than quality. As the undersheriff later whispered to Catchpoll, as they lay wrapped in their blankets and on the mill floor upon as many spare sacks as the miller could muster, his heart had not sunk as deep as the leaden dumplings that the lady of the house had fished up from the greasy depths of her pottage.

‘If you hear a strange thump in the night, Catchpoll, it is my insides, trying to move the foul things.’

‘They were not so bad, surely, my lord,’ whispered Walkelin, from the corner. ‘They were filling enough.’

‘Filling, perhaps, but so would a lump of iron be filling, and I do not recommend that,’ griped the undersheriff. ‘Now let us try and get some sleep. And if you snore, I shall kick you, Serjeant.’

Serjeant Catchpoll did not snore, but none of the three men slept well. Bradecote’s digestion was disordered, Catchpoll’s bones disliked the hard floor, and Walkelin woke with a nightmare in which he was being eaten alive by a huge, talking fish. Dawn saw them stifling yawns and rolling their blankets, keen to shake the mill dust from their boots, and indeed their hair. Catchpoll told Walkelin that he now had a good disguise for his memorable red mop.

They thanked the miller with polite lies, and in admiration of his stomach’s hardiness. Walkelin also murmured about his sore ears, but Catchpoll just grinned.

‘Now that marks you as a man unwed, young Walkelin. A married man could tell you that after a while a husband learns to “not hear” the majority of what his good woman says. The art is hearing the important parts and always seeming to be attending. It is a bit like the way your nose gets used to a smell and then does not smell it, even if you are a fuller or a tanner. All down to experience, of course, and that you only get with,’ he grinned his sepulchral, thin-lipped smile, ‘experience.’

‘And when you have finished giving Walkelin the benefit of your many years’ “experience”, Catchpoll, we will bid you farewell and see you tonight in Evesham, at the abbey guest hall. I know you will say we could sleep across the river at the castle, but I had to do service there two years back, and it is a draughty hole of a place that de Beauchamp has erected purely for defence, and seems to have carpenters working on it all hours of the day and night. I tell you, after a month there my head ached all the time. Right, you have more chance of finding news, I grant, for there are no hamlets at the water’s edge on the north bank, but we may find fishermen who use it often enough.’

‘I’ll try at Charlton for any who have been down by the river, but Hampton might be a better chance. The ferryman at least might have seen something, if I can get him to admit as much. He’s an observant old bird, like a heron − quiet, but knows his river, of course. I have come across him before, Kenelm the Ferryman.’

‘Until tonight, then,’ Bradecote wheeled his grey to the left, ‘and good hunting, Catchpoll.’

The trio split up. The undersheriff and serjeant’s apprentice made their way along the northern riverbank, stopping at every individual they met, whether a man mending a coracle or a lad fishing for minnows. They all looked blankly at the sheriff’s men, shaking their heads and denying any knowledge of a body in the river.

‘I had no real hopes, though the bend here means the river is slower and there is more chance of the body getting caught up, but from here to Evesham the bend puts the slower current with Serjeant Catchpoll. Hampton ferry could be key.’

Charlton gave Catchpoll as little success as his superior and junior. The villagers were dismissive. If there had been a body in the Avon, well, bodies floated downstream, so why should anyone take note of it? They had seen nothing. Catchpoll was torn between understanding and irritation. They were simple folk with a simple view of the world, and crime did not occur to them, unless it happened to them or theirs, and in a small village, everyone knew their neighbour’s business so well that opportunity for crime was very limited. The reeve was keen to recount how there had been a murder in the village in his father’s time, when a man had killed his wife for infidelity, but since those days the nearest thing they had to crimes were the odd defamatory comment or the emptying of an eel basket. The serjeant moved on along the bank to Hampton.

Hampton ferry had been worked by father and son for several generations. Some even laughed and said that Kenelm had been conceived on it. Kenelm merely shrugged. What people thought was their business, as long as it did not interfere with the ferry. He saw Catchpoll approaching, and gave him a slow nod.

‘Good day to you, Ferryman. The trade plies well?’

‘Well enough, Serjeant, well enough.’

‘There’s been a body washed into the leat at Fladbury. Man in a green jerkin. I was wondering where he went in, see, and thought to myself, there’s none keeps an eye on the Avon in these reaches more than Kenelm the Ferryman.’

The ferryman did not bat an eyelid at the compliment.

‘And?’

‘And so I am asking, if you saw anything green and man-sized pass by here.’

‘Friendly, or official?’

‘I prefers friendly, but if I don’t get the answers I wants, then it will be official.’

The ferryman permitted himself a twinkle in his heron-grey eyes.

‘In a friendly way, and in no part saying as the thing ever got nigh a bank, you understand, there was something large and green-clad, I might have noticed a-ways downstream about four days back. Now, I isn’t saying it was a corpse, just it was large and green and floating, and I am not talking of a lily pad.’

‘That’s fair enough, Ferryman. Much obliged.’ Catchpoll nodded in acknowledgement. ‘And now you can do me another good turn.’

‘Which is?’

‘Ferry me across to Evesham. Here’s coin for your pains.’

The ferryman smiled, and in almost companionable silence, the two men, and Catchpoll’s mount, crossed the Avon.