My Lamb, you are so very small,You have not learned to read at all;Yet never a printed book withstandsThe urgence of your dimpled hands.So, though this book is for yourself,Let mother keep it on the shelfTill you can read. O days that pass,That day will come too soon, alas!

BEAUTIFUL AS THE DAYThe house was three miles from the station, but, before the

dusty hired hack had rattled along for five minutes, the children

began to put their heads out of the carriage window and say,

"Aren't we nearly there?" And every time they passed a house, which

was not very often, they all said, "Oh,isthis it?" But it never was, till

they reached the very top of the hill, just past the chalk-quarry

and before you come to the gravel-pit. And then there was a white

house with a green garden and an orchard beyond, and mother said,

"Here we are!""How white the house is," said Robert."And look at the roses," said Anthea."And the plums," said Jane."It is rather decent," Cyril admitted.The Baby said, "Wanty go walky;" and the hack stopped with a

last rattle and jolt.Everyone got its legs kicked or its feet trodden on in the

scramble to get out of the carriage that very minute, but no one

seemed to mind. Mother, curiously enough, was in no hurry to get

out; and even when she had come down slowly and by the step, and

with no jump at all, she seemed to wish to see the boxes carried

in, and even to pay the driver, instead of joining in that first

glorious rush round the garden and orchard and the thorny, thistly,

briery, brambly wilderness beyond the broken gate and the dry

fountain at the side of the house. But the children were wiser, for

once. It was not really a pretty house at all; it was quite

ordinary, and mother thought it was rather inconvenient, and was

quite annoyed at there being no shelves, to speak of, and hardly a

cupboard in the place. Father used to say that the iron-work on the

roof and coping was like an architect's nightmare. But the house

was deep in the country, with no other house in sight, and the

children had been in London for two years, without so much as once

going to the seaside even for a day by an excursion train, and so

the White House seemed to them a sort of Fairy Palace set down in

an Earthly Paradise. For London is like prison for children,

especially if their relations are not rich.

That first glorious rush round the garden

Of course there are the shops and theatres, and

entertainments and things, but if your people are rather poor you

don't get taken to the theatres, and you can't buy things out of

the shops; and London has none of those nice things that children

may play with without hurting the things or themselves—such as

trees and sand and woods and waters. And nearly everything in

London is the wrong sort of shape—all straight lines and flat

streets, instead of being all sorts of odd shapes, like things are

in the country. Trees are all different, as you know, and I am sure

some tiresome person must have told you that there are no two

blades of grass exactly alike. But in streets, where the blades of

grass don't grow, everything is like everything else. This is why

many children who live in the towns are so extremely naughty. They

do not know what is the matter with them, and no more do their

fathers and mothers, aunts, uncles, cousins, tutors, governesses,

and nurses; but I know. And so do you, now. Children in the country

are naughty sometimes, too, but that is for quite different

reasons.The children had explored the gardens and the outhouses

thoroughly before they were caught and cleaned for tea, and they

saw quite well that they were certain to be happy at the White

House. They thought so from the first moment, but when they found

the back of the house covered with jasmine, all in white flower,

and smelling like a bottle of the most expensive perfume that is

ever given for a birthday present; and when they had seen the lawn,

all green and smooth, and quite different from the brown grass in

the gardens at Camden Town; and when they found the stable with a

loft over it and some old hay still left, they were almost certain;

and when Robert had found the broken swing and tumbled out of it

and got a bump on his head the size of an egg, and Cyril had nipped

his finger in the door of a hutch that seemed made to keep rabbits

in, if you ever had any, they had no longer any doubts

whatever.

Cyril had nipped his finger in the door of a hutch

The best part of it all was that there were no rules

about not going to places and not doing things. In London almost

everything is labelled "You mustn't touch," and though the label is

invisible it's just as bad, because you know it's there, or if you

don't you very soon get told.The White House was on the edge of a hill, with a wood behind

it—and the chalk-quarry on one side and the gravel-pit on the

other. Down at the bottom of the hill was a level plain, with

queer-shaped white buildings where people burnt lime, and a big red

brewery and other houses; and when the big chimneys were smoking

and the sun was setting, the valley looked as if it was filled with

golden mist, and the limekilns and hop-drying houses glimmered and

glittered till they were like an enchanted city out of theArabian Nights.Now that I have begun to tell you about the place, I feel

that I could go on and make this into a most interesting story

about all the ordinary things that the children did,—just the kind

of things you do yourself, you know, and you would believe every

word of it; and when I told about the children's being tiresome, as

you are sometimes, your aunts would perhaps write in the margin of

the story with a pencil, "How true!" or "How like life!" and you

would see it and would very likely be annoyed. So I will only tell

you the really astonishing things that happened, and you may leave

the book about quite safely, for no aunts and uncles either are

likely to write "How true!" on the edge of the story. Grown-up

people find it very difficult to believe really wonderful things,

unless they have what they call proof. But children will believe

almost anything, and grown-ups know this. That is why they tell you

that the earth is round like an orange, when you can see perfectly

well that it is flat and lumpy; and why they say that the earth

goes round the sun, when you can see for yourself any day that the

sun gets up in the morning and goes to bed at night like a good sun

as it is, and the earth knows its place, and lies as still as a

mouse. Yet I daresay you believe all that about the earth and the

sun, and if so you will find it quite easy to believe that before

Anthea and Cyril and the others had been a week in the country they

had found a fairy. At least they called it that, because that was

what it called itself; and of course it knew best, but it was not

at all like any fairy you ever saw or heard of or read

about.It was at the gravel-pits. Father had to go away suddenly on

business, and mother had gone away to stay with Granny, who was not

very well. They both went in a great hurry, and when they were gone

the house seemed dreadfully quiet and empty, and the children

wandered from one room to another and looked at the bits of paper

and string on the floors left over from the packing, and not yet

cleared up, and wished they had something to do. It was Cyril who

said—"I say, let's take our spades and dig in the gravel-pits. We

can pretend it's seaside.""Father says it was once," Anthea said; "he says there are

shells there thousands of years old."So they went. Of course they had been to the edge of the

gravel-pit and looked over, but they had not gone down into it for

fear father should say they mustn't play there, and it was the same

with the chalk-quarry. The gravel-pit is not really dangerous if

you don't try to climb down the edges, but go the slow safe way

round by the road, as if you were a cart.Each of the children carried its own spade, and took it in

turns to carry the Lamb. He was the baby, and they called him that

because "Baa" was the first thing he ever said. They called Anthea

"Panther," which seems silly when you read it, but when you say it

it sounds a little like her name.The gravel-pit is very large and wide, with grass growing

round the edges at the top, and dry stringy wildflowers, purple and

yellow. It is like a giant's washbowl. And there are mounds of

gravel, and holes in the sides of the bowl where gravel has been

taken out, and high up in the steep sides there are the little

holes that are the little front doors of the little bank-martins'

little houses.The children built a castle, of course, but castle-building

is rather poor fun when you have no hope of the swishing tide ever

coming in to fill up the moat and wash away the drawbridge, and, at

the happy last, to wet everybody up to the waist at

least.Cyril wanted to dig out a cave to play smugglers in, but the

others thought it might bury them alive, so it ended in all spades

going to work to dig a hole through the castle to Australia. These

children, you see, believed that the world was round, and that on

the other side the little Australian boys and girls were really

walking wrong way up, like flies on the ceiling, with their heads

hanging down into the air.The children dug and they dug and they dug, and their hands

got sandy and hot and red, and their faces got damp and shiny. The

Lamb had tried to eat the sand, and had cried so hard when he found

that it was not, as he had supposed, brown sugar, that he was now

tired out, and was lying asleep in a warm fat bunch in the middle

of the half-finished castle. This left his brothers and sisters

free to work really hard, and the hole that was to come out in

Australia soon grew so deep that Jane, who was called Pussy for

short, begged the others to stop."Suppose the bottom of the hole gave way suddenly," said she,

"and you tumbled out among the little Australians, all the sand

would get in their eyes.""Yes," said Robert; "and they would hate us, and throw stones

at us, and not let us see the kangaroos, or opossums, or bluegums,

or Emu Brand birds, or anything."Cyril and Anthea knew that Australia was not quite so near as

all that, but they agreed to stop using the spades and to go on

with their hands. This was quite easy, because the sand at the

bottom of the hole was very soft and fine and dry, like sea-sand.

And there were little shells in it."Fancy it having been wet sea here once, all sloppy and

shiny," said Jane, "with fishes and conger-eels and coral and

mermaids.""And masts of ships and wrecked Spanish treasure. I wish we

could find a gold doubloon, or something," Cyril said."How did the sea get carried away?" Robert

asked."Not in a pail, silly," said his brother."Father says the earth got too hot underneath, as you do in

bed sometimes, so it just hunched up its shoulders, and the sea had

to slip off, like the blankets do us, and the shoulder was left

sticking out, and turned into dry land. Let's go and look for

shells; I think that little cave looks likely, and I see something

sticking out there like a bit of wrecked ship's anchor, and it's

beastly hot in the Australian hole."The others agreed, but Anthea went on digging. She always

liked to finish a thing when she had once begun it. She felt it

would be a disgrace to leave that hole without getting through to

Australia.The cave was disappointing, because there were no shells, and

the wrecked ship's anchor turned out to be only the broken end of a

pick-axe handle, and the cave party were just making up their minds

that sand makes you thirstier when it is not by the seaside, and

someone had suggested that they all go home for lemonade, when

Anthea suddenly screamed—"Cyril! Come here! Oh, come quick—It's alive! It'll get away!

Quick!"They all hurried back."It's a rat, I shouldn't wonder," said Robert. "Father says

they infest old places—and this must be pretty old if the sea was

here thousands of years ago"—"Perhaps it is a snake," said Jane, shuddering."Let's look," said Cyril, jumping into the hole. "I'm not

afraid of snakes. I like them. If it is a snake I'll tame it, and

it will follow me everywhere, and I'll let it sleep round my neck

at night.""No, you won't," said Robert firmly. He shared Cyril's

bedroom. "But you may if it's a rat."

Anthea suddenly screamed, "It's alive!"

"Oh, don't be silly!" said Anthea; "it's not a rat,

it'smuchbigger. And it's not a

snake. It's got feet; I saw them; and fur! No—not the spade. You'll

hurt it! Dig with your hands.""And letithurtmeinstead! That's so likely, isn't

it?" said Cyril, seizing a spade."Oh, don't!" said Anthea. "Squirrel,don't. I—it sounds silly, but it said

something. It really and truly did"—"What?""It said, 'You let me alone.'"But Cyril merely observed that his sister must have gone off

her head, and he and Robert dug with spades while Anthea sat on the

edge of the hole, jumping up and down with hotness and anxiety.

They dug carefully, and presently everyone could see that there

really was something moving in the bottom of the Australian

hole.Then Anthea cried out, "I'mnot afraid. Let me dig," and fell on her knees and began to

scratch like a dog does when he has suddenly remembered where it

was that he buried his bone."Oh, I felt fur," she cried, half laughing and half crying.

"I did indeed! I did!" when suddenly a dry husky voice in the sand

made them all jump back, and their hearts jumped nearly as fast as

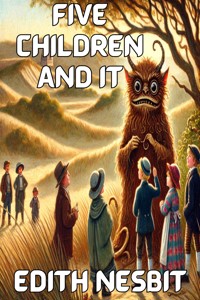

they did."Let me alone," it said. And now everyone heard the voice and

looked at the others to see if they had heard it too."But we want to see you," said Robert bravely."I wish you'd come out," said Anthea, also taking

courage."Oh, well—if that's your wish," the voice said, and the sand

stirred and spun and scattered, and something brown and furry and

fat came rolling out into the hole, and the sand fell off it, and

it sat there yawning and rubbing the ends of its eyes with its

hands."I believe I must have dropped asleep," it said, stretching

itself.The children stood round the hole in a ring, looking at the

creature they had found. It was worth looking at. Its eyes were on

long horns like a snail's eyes, and it could move them in and out

like telescopes; it had ears like a bat's ears, and its tubby body

was shaped like a spider's and covered with thick soft fur; its

legs and arms were furry too, and it had hands and feet like a

monkey's."What on earth is it?" Jane said. "Shall we take it

home?"The thing turned its long eyes to look at her, and

said—"Does she always talk nonsense, or is it only the rubbish on

her head that makes her silly?"It looked scornfully at Jane's hat as it spoke."She doesn't mean to be silly," Anthea said gently; "we none

of us do, whatever you may think! Don't be frightened; we don't

want to hurt you, you know.""Hurtme!" it said.

"Mefrightened? Upon my word!

Why, you talk as if I were nobody in particular." All its fur stood

out like a cat's when it is going to fight."Well," said Anthea, still kindly, "perhaps if we knew who

you are in particular we could think of something to say that

wouldn't make you angry. Everything we've said so far seems to have

done so. Who are you? And don't get angry! Because really we don't

know.""You don't know?" it said. "Well, I knew the world had

changed—but—well, really—Do you mean to tell me seriously you don't

know a Psammead when you see one?""A Sammyadd? That's Greek to me.""So it is to everyone," said the creature sharply. "Well, in

plain English, then, aSand-fairy. Don't you know a Sand-fairy when you see one?"It looked so grieved and hurt that Jane hastened to say, "Of

course I see you are,now. It's

quite plain now one comes to look at you.""You came to look at me, several sentences ago," it said

crossly, beginning to curl up again in the sand."Oh—don't go away again! Do talk some more," Robert cried. "I

didn't know you were a Sand-fairy, but I knew directly I saw you

that you were much the wonderfullest thing I'd ever

seen."The Sand-fairy seemed a shade less disagreeable after

this."It isn't talking I mind," it said, "as long as you're

reasonably civil. But I'm not going to make polite conversation for

you. If you talk nicely to me, perhaps I'll answer you, and perhaps

I won't. Now say something."Of course no one could think of anything to say, but at last

Robert thought of "How long have you lived here?" and he said it at

once."Oh, ages—several thousand years," replied the

Psammead."Tell us about it. Do.""It's all in books.""Youaren't!" Jane said.

"Oh, tell us everything you can about yourself! We don't know

anything about you, and youareso nice."The Sand-fairy smoothed his long rat-like whiskers and smiled

between them."Do please tell!" said the children all

together.It is wonderful how quickly you get used to things, even the

most astonishing. Five minutes before, the children had had no more

idea than you had that there was such a thing as a Sand-fairy in

the world, and now they were talking to it as though they had known

it all their lives.It drew its eyes in and said—"How very sunny it is—quite like old times! Where do you get

your Megatheriums from now?""What?" said the children all at once. It is very difficult

always to remember that "what" is not polite, especially in moments

of surprise or agitation."Are Pterodactyls plentiful now?" the Sand-fairy went

on.The children were unable to reply."What do you have for breakfast?" the Fairy said impatiently,

"and who gives it to you?""Eggs and bacon, and bread and milk, and porridge and things.

Mother gives it to us. What are Mega-what's-its-names and

Ptero-what-do-you-call-thems? And does anyone have them for

breakfast?""Why, almost everyone had Pterodactyl for breakfast in my

time! Pterodactyls were something like crocodiles and something

like birds—I believe they were very good grilled. You see, it was

like this: of course there were heaps of Sand-fairies then, and in

the morning early you went out and hunted for them, and when you'd

found one it gave you your wish. People used to send their little

boys down to the seashore in the morning before breakfast to get

the day's wishes, and very often the eldest boy in the family would

be told to wish for a Megatherium, ready jointed for cooking. It

was as big as an elephant, you see, so there was a good deal of

meat on it. And if they wanted fish, the Ichthyosaurus was asked

for,—he was twenty to forty feet long, so there was plenty of him.

And for poultry there was the Plesiosaurus; there were nice

pickings on that too. Then the other children could wish for other

things. But when people had dinner-parties it was nearly always

Megatheriums; and Ichthyosaurus, because his fins were a great

delicacy and his tail made soup.""There must have been heaps and heaps of cold meat left

over," said Anthea, who meant to be a good housekeeper some

day."Oh no," said the Psammead, "that would never have done. Why,

of course at sunset what was left over turned into stone. You find

the stone bones of the Megatherium and things all over the place

even now, they tell me.""Who tell you?" asked Cyril; but the Sand-fairy frowned and

began to dig very fast with its furry hands."Oh, don't go!" they all cried; "tell us more about when it

was Megatheriums for breakfast! Was the world like this

then?"It stopped digging."Not a bit," it said; "it was nearly all sand where I lived,

and coal grew on trees, and the periwinkles were as big as

tea-trays—you find them now; they're turned into stone. We

Sand-fairies used to live on the seashore, and the children used to

come with their little flint-spades and flint-pails and make

castles for us to live in. That's thousands of years ago, but I

hear that children still build castles on the sand. It's difficult

to break yourself of a habit.""But why did you stop living in the castles?" asked

Robert."It's a sad story," said the Psammead gloomily. "It was

because theywouldbuild moats

to the castles, and the nasty wet bubbling sea used to come in, and

of course as soon as a Sand-fairy got wet it caught cold, and

generally died. And so there got to be fewer and fewer, and,

whenever you found a fairy and had a wish, you used to wish for a

Megatherium, and eat twice as much as you wanted, because it might

be weeks before you got another wish.""And didyouget wet?"

Robert inquired.The Sand-fairy shuddered. "Only once," it said; "the end of

the twelfth hair of my top left whisker—I feel the place still in

damp weather. It was only once, but it was quite enough for me. I

went away as soon as the sun had dried my poor dear whisker. I

scurried away to the back of the beach, and dug myself a house deep

in warm dry sand, and there I've been ever since. And the sea

changed its lodgings afterwards. And now I'm not going to tell you

another thing.""Just one more, please," said the children. "Can you give

wishes now?""Of course," said it; "didn't I give you yours a few minutes

ago? You said, 'I wish you'd come out,' and I did.""Oh, please, mayn't we have another?""Yes, but be quick about it. I'm tired of you."I daresay you have often thought what you would do if you had

three wishes given you, and have despised the old man and his wife

in the black-pudding story, and felt certain that if you had the

chance you could think of three really useful wishes without a

moment's hesitation. These children had often talked this matter

over, but, now the chance had suddenly come to them, they could not

make up their minds."Quick," said the Sand-fairy crossly. No one could think of

anything, only Anthea did manage to remember a private wish of her

own and Jane's which they had never told the boys. She knew the

boys would not care about it—but still it was better than

nothing."I wish we were all as beautiful as the day," she said in a

great hurry.The children looked at each other, but each could see that

the others were not any better-looking than usual. The Psammead

pushed out his long eyes, and seemed to be holding its breath and

swelling itself out till it was twice as fat and furry as before.

Suddenly it let its breath go in a long sigh."I'm really afraid I can't manage it," it said

apologetically; "I must be out of practice."The children were horribly disappointed."Oh,dotry again!" they

said."Well," said the Sand-fairy, "the fact is, I was keeping back

a little strength to give the rest of you your wishes with. If

you'll be contented with one wish a day among the lot of you I

daresay I can screw myself up to it. Do you agree to

that?""Yes, oh yes!" said Jane and Anthea. The boys nodded. They

did not believe the Sand-fairy could do it. You can always make

girls believe things much easier than you can boys.It stretched out its eyes farther than ever, and swelled and

swelled and swelled."I do hope it won't hurt itself," said Anthea."Or crack its skin," Robert said anxiously.Everyone was very much relieved when the Sand-fairy, after

getting so big that it almost filled up the hole in the sand,

suddenly let out its breath and went back to its proper

size."That's all right," it said, panting heavily. "It'll come

easier to-morrow.""Did it hurt much?" said Anthea."Only my poor whisker, thank you," said he, "but you're a

kind and thoughtful child. Good day."It scratched suddenly and fiercely with its hands and feet,

and disappeared in the sand.Then the children looked at each other, and each child

suddenly found itself alone with three perfect strangers, all

radiantly beautiful.They stood for some moments in silence. Each thought that its

brothers and sisters had wandered off, and that these strange

children had stolen up unnoticed while it was watching the swelling

form of the Sand-fairy. Anthea spoke first—"Excuse me," she said very politely to Jane, who now had

enormous blue eyes and a cloud of russet hair, "but have you seen

two little boys and a little girl anywhere about?""I was just going to ask you that," said Jane. And then Cyril

cried—"Why, it'syou! I know

the hole in your pinafore! YouareJane, aren't you? And you're the Panther; I can see your

dirty handkerchief that you forgot to change after you'd cut your

thumb! The wishhascome off,

after all. I say, am I as handsome as you are?""If you're Cyril, I liked you much better as you were

before," said Anthea decidedly. "You look like the picture of the

young chorister, with your golden hair; you'll die young, I

shouldn't wonder. And if that's Robert, he's like an Italian

organ-grinder. His hair's all black.""You two girls are like Christmas cards, then—that's

all—silly Christmas cards," said Robert angrily. "And Jane's hair

is simply carrots."It was indeed of that Venetian tint so much admired by

artists."Well, it's no use finding fault with each other," said

Anthea; "let's get the Lamb and lug it home to dinner. The servants

will admire us most awfully, you'll see."Baby was just waking up when they got to him, and not one of

the children but was relieved to find that he at least was not as

beautiful as the day, but just the same as usual."I suppose he's too young to have wishes naturally," said

Jane. "We shall have to mention him specially next

time."Anthea ran forward and held out her arms."Come, then," she said.The Baby looked at her disapprovingly, and put a sandy pink

thumb in his mouth. Anthea was his favourite sister."Come, then," she said."G'way 'long!" said the Baby."Come to own Pussy," said Jane."Wants my Panty," said the Lamb dismally, and his lip

trembled."Here, come on, Veteran," said Robert, "come and have a yidey

on Yobby's back.""Yah, narky narky boy," howled the Baby, giving way

altogether. Then the children knew the worst.The

Baby did not know them!

The baby did not know them!

They looked at each other in despair, and it was

terrible to each, in this dire emergency, to meet only the

beautiful eyes of perfect strangers, instead of the merry,

friendly, commonplace, twinkling, jolly little eyes of its own

brothers and sisters."This is most truly awful," said Cyril when he had tried to

lift up the Lamb, and the Lamb had scratched like a cat and

bellowed like a bull! "We've got tomake

friendswith him! I can't carry him home

screaming like that. Fancy having to make friends with our own

baby!—it's too silly."That, however, was exactly what they had to do. It took over

an hour, and the task was not rendered any easier by the fact that

the Lamb was by this time as hungry as a lion and as thirsty as a

desert.At last he consented to allow these strangers to carry him

home by turns, but as he refused to hold on to such new

acquaintances he was a dead weight, and most

exhausting."Thank goodness, we're home!" said Jane, staggering through

the iron gate to where Martha, the nursemaid, stood at the front

door shading her eyes with her hand and looking out anxiously.

"Here! Do take Baby!"Martha snatched the Baby from her arms."Thanks be,he'ssafe

back," she said. "Where are the others, and whoever to goodness

gracious are all of you?""We'reus, of course,"

said Robert."And who's Us, when you're at home?" asked Martha

scornfully."I tell you it'sus, only

we're beautiful as the day," said Cyril. "I'm Cyril, and these are

the others, and we're jolly hungry. Let us in, and don't be a silly

idiot."Martha merely dratted Cyril's impudence and tried to shut the

door in his face."I know welookdifferent,

but I'm Anthea, and we're so tired, and it's long past

dinner-time.""Then go home to your dinners, whoever you are; and if our

children put you up to this play-acting you can tell them from me

they'll catch it, so they know what to expect!" With that she did

bang the door. Cyril rang the bell violently. No answer. Presently

cook put her head out of a bedroom window and said—"If you don't take yourselves off, and that precious sharp,

I'll go and fetch the police." And she slammed down the

window."It's no good," said Anthea. "Oh, do, do come away before we

get sent to prison!"The boys said it was nonsense, and the law of England

couldn't put you in prison for just being as beautiful as the day,

but all the same they followed the others out into the

lane."We shall be our proper selves after sunset, I suppose," said

Jane."I don't know," Cyril said sadly; "it mayn't be like that

now—things have changed a good deal since Megatherium

times.""Oh," cried Anthea suddenly, "perhaps we shall turn into

stone at sunset, like the Megatheriums did, so that there mayn't be

any of us left over for the next day."She began to cry, so did Jane. Even the boys turned pale. No

one had the heart to say anything.