0,93 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Alien Ebooks

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

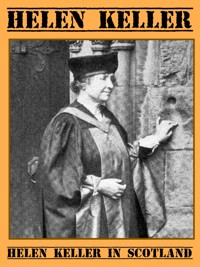

Helen Keller in Scotland: A Personal Record, written by Helen Keller herself, provides a detailed account of her travels and experiences in Scotland. Originally published in 1933, it offers insights into Keller's thoughts and reflections during her visit.

The book is edited with an introduction by James Kerr Love, a notable figure in the field of audiology, who adds valuable context to Keller's narrative. It captures her admiration for the Scottish landscape and culture, showcasing her ability to appreciate and describe the world despite her disabilities. This work remains a testament to Keller's determination and keen observational skills, providing readers with a unique perspective on her life and experiences in Scotland

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 226

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

HELEN KELLER IN

SCOTLAND

Written by Herself

Edited and with an Introduction by James Kerr Love

HELEN KELLER IN HER DOCTOR’S ROBESAT THE PRIEST’S DOOR, BOTHWELL KIRK

First Published in 1933

PREFACE

This collection of letters and speeches records chiefly experiences surrounding the Honorary Degree conferred upon me by the University of Glasgow last June. The material has been collected and edited by Dr. James Kerr Love, my friend of a quarter of a century. Dr. Love and other friends in Scotland felt that there should be some permanent record of this most significant event in my life. While I am deeply grateful to Dr. Love for the trouble and thought he has put into this volume, he must, if it should be considered presumptuous and the personal element over-emphasized, accept the responsibility.

When the letters were written I had no idea that other eyes than those of the friends to whom they were addressed would read them. The speeches were composed hurriedly as I went from one function to another. The only reason for printing them is the hope that the story they tell of the general outlook upon the education of the handicapped and the lesson they teach of courage and victory over limitation, may prove of some interest and value to people with unimpaired faculties.

If these utterances and happy memories impart a sense of the marvellous kindness that gave my visit to Scotland the glamour of a royal progress, I shall be content. I should like my friends to think of this book as a garland of enkindling experiences woven to coax them for a little while into the bypaths of the deaf and the blind, and, once there, to keep them glad they came; a book easy to take up and lay down, with perhaps a helpful thought or two for the discouraged, and glimpses of a world of dark silence that is beautiful withal.

As I look over these pages, candour prompts the admission that I may have filched phrases from H. V. Morton’s enchanting book, In Search of Scotland. If so, he will not miss them out of his wealth of golden words. I have had such joy in his book that it would be strange if my thoughts did not often keep time to the music of his spirited narrative.

HELEN KELLER

Forest Hills, L.I., N.Y.

October 24, 1932

HELEN KELLER IN

SCOTLAND

INTRODUCTION

Helen Keller was born at Tuscumbia, Alabama, in June 1880, a quite normal child. At the age of nineteen months she was struck quite blind and quite deaf by illness, and soon all speech and language disappeared. For five years she led the life of a misunderstood and misunderstanding child. Through the agency of Dr. Graham Bell of telephone fame—himself once a teacher of the deaf, and married to a deaf wife—a teacher was found for Helen in the person of Anne Sullivan, now Mrs. Macy. Never was happier combination of great need and ability to serve. After a struggle in darkness and silence, light re-entered Helen’s mind through the agency of signs and finger-spelling; rebellion gave place to obedience, and the progress of the pupil was rapid. At the age of ten Helen declared that she must speak. This astonishing proposal was one which it had never occurred to those about her to make. But upon its being acceded to her progress was again rapid. It became clear to Miss Sullivan that she had under her care a brilliant and unusual pupil. In due course Helen entered college and, without favour or concession of any kind, graduated in arts. The story of her life is told fully in her books, The Story of My Life and Midstream, while in The World I Live In she has much to say of her moods and pleasures. Enough has been said here to prepare the reader for the perusal of her book on Scotland.

I have known Helen Keller for over a quarter of a century. There was a long-standing promise that she should visit me at West Kilbride when circumstances should allow. The date of the visit was eventually determined in 1932 by the action of the University of Glasgow in conferring upon her the Honorary Degree of Doctor of Laws. The late Professor William James, one of her greatest admirers, described her as ‘a blessing’, and offered to kill anyone who denied this. I, too, think her a blessing, and I looked to her visit to help me to convert the unbelieving and make them missionaries for the deaf. She has fulfilled all my hopes.

Looking back upon my knowledge of Helen Keller, I find that it passed through three stages. There was, first, the pathetic or ‘poor thing’ stage—creditable to the heart, but not of long duration.

This was succeeded by a feeling of admiration, for the pluck, patience, and fortitude which have overcome apparently insuperable difficulties. Most people reach and rest in this stage, and do not know whether to admire more Helen Keller or her beloved teacher, Anne Sullivan, now Mrs. Macy.

Finally came the stage of sheer joy and inspiration in the presence of a great and happy personality.

Professor Macneile Dixon sums up the characteristics of the average Englishman as ‘toleration, humour, humanity’. There you have Helen Keller. But I must add one feature which cannot be claimed for the average Englishman—an absolute assurance of spiritual companionship both in this world and in any world which may follow it. It is this element which gives to Helen Keller the fight which dispels all darkness, the ear which hears music everywhere, and a well-balanced mind over-flowing with ‘gallant and high-hearted happiness’.

Here I can hardly do better than quote what Mr. W. W. McKechnie said of her on June 10, 1932, at the ceremony at which she was presented with her graduation robes.

‘The emancipation of Helen Keller is one of the marvels of educational achievement, brimful of interest and value to Miss Keller herself, and no less full of significance for education in general. While for me, as an individual, it is a rare privilege to preside over your meeting, it is no mere form of words to say that it is a privilege that carries with it a haunting sense of inadequacy. But it would be utterly inconsistent with one of the main lessons of Helen Keller’s life if any of us to-day were to shrink from a task simply because it was difficult.

‘When Miss Keller was a girl of seven she wrote a letter in which she said: “When I go to France I will talk French.” A little French boy will say “Parlez-vous français?” and I will say “Oui, Monsieur, vous avez un joli chapeau. Donnez-moi un baiser.” And in the same letter she used several little Greek phrases: se agapo, I love you; pos echete, how do you do?; chaere, good-bye. That was her Greek at seven. Ten or eleven years later she was simply revelling in Greek and especially in Homer. Of Greek she said: “I think Greek is the loveliest language that I know anything about. If it is true that the violin is the most perfect of musical instruments, then Greek is the violin of human thought.” Surely, then, no one will take it amiss if I allow myself one Greek proverb. It is chalepa ta kala—what is noble is difficult—and it is with that proverb in my mind that I approach my difficult task.

‘Helen Keller has a genius for friendship. Of her friends she says: “They have made the story of my life. In a thousand ways they have turned my limitations into beautiful privileges, and enabled me to walk serene and happy in the shadow cast by my deprivation.” It is sheer joy to see the affection that has existed between her and many of the most distinguished men of her time—Bishop Brooks, Graham Bell, Whittier, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Mark Twain. Of Mark Twain she once said: “His heart is a tender Iliad of human sympathy.” What did Mark Twain say of her? That Napoleon and Helen Keller were the two most interesting persons in the nineteenth century. That is an amazing combination, and coming from Mark Twain it deserves very serious consideration. You will agree with me that the emancipation of Helen Keller from the doom that threatened her almost makes us think that the age of miracles is not dead, any more than the age of chivalry. When we think of her before and after she was restored to her human heritage, we are reminded of La Belle au Bois Dormant and of Ariel. The Sleeping Beauty was imprisoned in the Castle where all was death, till the Prince came and set her free; Ariel was confined in a cloven pine, till Prospero “Made gape the pine and let him out”. Ladies and gentlemen, if Helen Keller is our Ariel and our Belle au Bois Dormant, there is no doubt as to who was cast by destiny for the roles of Le Prince and Prospero. Whittier called Miss Sullivan “the spiritual liberator” of Helen Keller. All honour to Miss Sullivan, Mrs. Macy as she is now, for the genius, untiring perseverance and devotion of her services to her pupil and friend. I have had experience of every kind of teaching, and I am sure that none is so arduous as the teaching of the deaf. When blindness is added to deafness, the task is one for heroes and for heroes alone. I am sure we are all glad to have Mrs. Macy with us this evening.

‘The life of Helen Keller is one of the greatest triumphs of the educator. It is at the same time one of the most inspiring and inspiriting arguments for education that exist in the records of the race. How many imprisoned Ariels has the world lost for want of the culture and encouragement that were needed? It is some consolation to us to know that in our own country the number is small and is every year growing smaller.

‘But we must not exaggerate. There is not an Ariel in every tree, and all the Miss Sullivans in the world could never evoke qualities that are not latent, implanted in their pupils by Nature. There have been many other deaf and blind children. Dickens told us of two of them in his American Notes—Laura Bridgman and Oliver Caswell—and it is most interesting to know that Helen Keller’s mother had her first ray of hope when she read Dickens’s account of what had been done for Laura Bridgman. But few or none of them had the altogether exceptional gifts of the lady we are met to honour.

‘It is embarrassing to speak of Miss Keller in her presence. But I must. And I may be forgiven for recalling the fact that she was sometimes a naughty child—with all the rich promise that naughtiness conveys to the teacher or parent who has the sense and the heart to understand. And as soon as the cruel barriers were beaten down her precocity was manifest. She loved the art of composition. By the age of thirteen she was deeply interested in the history of Greece, Rome, and the United States. Latin Grammar she did not take to at first. Why parse every word? Would it not be at least as useful, she asks, to describe her cat—order, vertebrate; division, quadruped; class, mammalia; genus, felinus; species, cat; individual, Tabby? At that time this amazing child tried, without aid, to master French pronunciation. “It gave me something to do on a rainy day!” And she felt the joy of translating Latin! Arithmetic she found as troublesome as it was uninteresting. I do think our young friend might well have been spared some, if not all, of her mathematical troubles. Her heart was in language. “I cannot see why it is so very important to know that the lines drawn from the extremities of the base of an isosceles triangle to the middle points of the opposite sides are equal. The knowledge doesn’t make life any sweeter or happier. But a new word learned is the key to untold treasure.”

‘Then came College—a most interesting chapter of her life. Listen to her on note-taking in lectures, which critics have been girding against in Scotland for centuries: “If the mind is occupied with the mechanical process of hearing and putting words on paper at pell-mell speed, one cannot pay much attention to the subject or the manner in which it is presented.” At first some disillusionment! “When one enters the portals of learning, one leaves the dearest pleasures—solitude, books, and imagination—outside with the whispering pines.” Her criticism of pedantry is admirable. And listen to her on examinations. You should read the passage in full. Here is a quotation: “But the examinations are the chief bugbears of my life. Although I have faced them many times and cast them down and made them bite the dust, yet they rise again and menace me with pale looks, until, like Bob Acres, I feel my courage oozing out at my finger ends.” “Those dreadful pitfalls called examinations”, she says again, “set by schools and colleges for the confusion of those who seek knowledge.”

‘What surprises me most of all is that in spite of everything she became so soon such a mistress of language, that she wrote so well and that she appreciated literature with such taste and discrimination. The proof of this is everywhere in her writings—what she says about authors in English, French, Latin, Greek, the Bible, about Shakespeare, Burke, Macaulay, La Fontaine, Virgil, Homer.

‘But best of all is the moral outlook. Her courage, her humour, her self-forgetfulness. She feels the bitterness of her fate. “Silence sits immense upon my soul. Then comes hope with a smile and whispers ‘There is joy in self-forgetfulness.’ So I try to make the light in others’ eyes my sun, the music in others’ ears my symphony, the smile on others’ lips my happiness.” We recall her warm friendships, her God-given sense of humour, her deep gratitude to all her teachers, her love of children, her pity for the poor, the weary, and the heavy-laden. We think of her indomitable courage and perseverance: “I slip back many times, I fall, I stand still, I run against the edge of hidden obstacles, I lose my temper and find it again and keep it better, I trudge on, I gain a little, I feel encouraged, I get more eager and climb higher and begin to see the widening horizon. Every struggle is a victory. One more effort and I reach the luminous cloud, the blue depths of the sky, the uplands of my desire.” And last her superb optimism.

‘ “I love”, she wrote, “Mark Twain. Who does not? The gods, too, loved him and put into his heart all manner of wisdom; then, fearing lest he should become a pessimist, they spanned his mind with a rainbow of love and faith. I love all writers whose minds, like Lowell’s, bubble up in the sunshine of optimism—fountains of joy and goodwill, with occasionally a splash of anger here and there, a healing spray of sympathy and pity.” ’

I have by me a unique book—an Anthology to Helen Keller. I like the musical Greek word, which of course means a garland. We are accustomed to anthologies, collections of verses compiled by someone and sold for a certain figure. But this one, called Double Blossoms, is a collection of over seventy poems about or addressed to Helen Keller. I wonder whether in the history of literature such a tribute has ever been paid to a living author? No wonder she was apostrophized by Clarence Stedman, the American poet, in these terms:

‘Not thou! Not thou!

’Tis we are Blind and Deaf and Dumb.’

Helen Keller’s visit to Scotland in 1932 was not the first she had paid to our shores, as a letter which follows will show; her first visit was in 1930 (see p. 85). But then she came for rest—rest for herself and, perhaps more, for her teacher and life-long friend, Mrs. Macy; and that she was justified in thus seeking seclusion was proved by her experience in 1932, when she received incessant calls to make public appearances. In 1931 Helen visited France and made a journey to Yugo-Slavia, where she was the guest of that country and of its King, and did valuable work for the Blind. Most of Helen’s work has been in the interests of the Blind. I was anxious that she should help the Deaf in Britain so that the interests of these equally afflicted ones should no longer remain in the position of relative neglect which they occupied before her visit.

In reading the book which follows, two questions will strike the reader as requiring an answer: What does Helen Keller mean when she talks of ‘seeing’ things? and, How does she work? I have sometimes been tempted to write on ‘The Mind of Helen Keller’, but I have always been deterred by two considerations: the difficulty of the task, and the fact that in her book The World I Live In, which is shortly to be published in an English edition, she has herself done more than perhaps any author could to analyse and expose her mind.

In answering the first question, then, I will quote from The World I Live In. From a newspaper for the blind Helen Keller cites the following sentences:

‘Many poems and stories must be omitted because they deal with sight. Allusions to moonbeams, rainbows, starlight, clouds, and beautiful scenery may not be printed because they serve to emphasize the blind man’s sense of his affliction.’

‘That is to say’, she comments, ‘I may not talk about beautiful mansions and gardens because I am poor. I may not read about Paris and the West Indies because I cannot visit them in their territorial reality. I may not dream of heaven because it is possible I may never go there. Yet a venturesome spirit impels me to use words of sight and sound whose meaning I can guess only from analogy and fancy. Critics delight to tell us what we cannot do. They assume that blindness severs us completely from the things which the seeing and hearing enjoy, and hence assert that we have no moral right to talk about beauty, the skies, mountains, the song of birds, and colours. They declare that the very sensations which we have from the sense of touch are “vicarious”, as though our friends felt the sun for us.’

Later in the same volume she remarks: ‘Many persons having perfect eyes are blind in their perceptions. Many persons having perfect ears are emotionally deaf. Yet these are the very ones who dare to set limits to the vision of those who, lacking a sense or two, have will, soul, passion, imagination.’ I may add that most of the impressions of us five-sensed people, although based on sight and hearing, are really composite and completed by descriptions we have read and forgotten but on which the imagination continues to work. Further, it must not be forgotten that from birth till nearly two years of age Helen had her sight and hearing, and, although she cannot define it, something remains of that bright childhood. To these possessions must be added a very retentive memory, a very vivid imagination, and something of that incalculable thing we call genius.

Consider her description of Skye (see p. 58), which is really a prose-poem. Starting with the meagre foundation of impressions reaching her through her remaining senses, she derives further information from Miss Thomson, who spells into her hand observations on the scenery. But neither Miss Thomson nor any one else could paint the resulting picture. As Helen has indicated in her Preface, the influence of H. V. Morton may be traced in this piece; but the picture—the prose-poem—is her own.

I can give another instance from personal experience. During a motor run from West Kilbride to Gleneagles Hotel in Perthshire, talk ranged over many subjects, and occasional references were made by Miss Thomson to the nature of the country traversed, the words being spoken, for our benefit, as they were spelled into Helen’s hand. The day was wet and misty and the scenery not of the striking type of Skye. Helen alone thought of drawing poetry out of a wet day. The same evening she sent me the following:

‘Gleneagles

June 28, 1932

‘It is not raining rain for me,

It’s raining wild-flowers on the hills!

Let clouds and Scotch mists engulf the sky,

It is not raining rain to me,

It’s raining mounds of golden broom!

‘I salute the happy!

I have no use for him who frets—

A fig for mists and clouds!

It is not raining rain for me,

It’s raining scented briar and larks to-day,

And all of them are saying, “Earth, it is well!”

And all of them are singing, “Life, thou art good!” ’

The second point, How does Helen Keller work? is best illustrated by her preparation of a platform speech. Helen types what she means to say on an ordinary type-writer, and the typescript is then read to her by the fingers and any necessary corrections made. When perfect, the speech is rewritten with her own fingers in Braille, from which version she reads it until she is memory-perfect and ready to deliver it.

HELEN KELLER READING DR. KERR LOVE’S LIPSAT ‘SUNNYSIDE’, WEST KILBRIDE

The system of finger-spelling familiar to the British public is the two-hand system which is used by the seeing deaf and in addressing the deaf and dumb. But with the blind-deaf like Helen Keller this method is useless. So the one-hand alphabet, spelt from hand to hand, which is probably of Monastic origin, is used by Mrs. Macy and Miss Thomson when direct speech-reading is not possible. Helen Keller’s own speech, and her power to read the speech of others by placing her fingers on the lips of the speaker, are perhaps her most spectacular triumphs. This lip- or rather speech-reading she effects by the contact of her thumb on the larynx and her fingers over the lips or lower part of the face of the speaker; by this means, if the speaker speaks slowly, she succeeds in understanding the words (see Plate facing page 14).

My editorship of this book became necessary when, immediately on her return to America, Helen Keller was plunged into strenuous work for the Blind. The work on Part I was trifling, only a few names of places and persons requiring attention. But the letters in Part II had to be collected from their recipients and any unnecessary repetition eliminated from them. This, in several cases, I found difficult; for the letters were written, for the most part, from one address and during a single month, and accordingly repetition was almost inevitable. If, therefore, in my literary surgery, I have cut out from letters passages which their recipients treasure, I hope I shall be forgiven.

My thanks—and I am sure Helen Keller’s—are due to the recipients of the letters for so kindly furnishing copies. Thanks are due also to Mr. D. MacGillivray, LL.D., for reading the manuscript, and to the Rev. J. Wales Cameron, M.A., for correcting the proofs.

JAMES KERR LOVE

Sunnyside

West Kilbride

Ayrshire

PART IMY PILGRIMAGE

As Fate would have it, the honorary degree conferred upon me by the University of Glasgow in June 1932 cheated us out of the greater part of our holiday. Even in lovely Looe, where we spent most of May, we were under a constant barrage of reporters, photographers, callers, telegrams, and telephone messages. Polly[1] and I rose at six in the morning to get a walk before the fray began. We were literally deluged with invitations of all kinds, and often Polly wrote twenty letters between breakfast and dinner, while I worked on magazine articles and prepared my speeches for the robing and graduation ceremonies.

After our arrival in Scotland the fusillade became more lively, and continued unabated until the end of June. There was some sort of function practically every day. Of course I was glad to visit the schools for the blind and the deaf in Edinburgh and Glasgow about which I had read since I was a child, and to meet friends whose kindness I had so long felt from afar.

Dr. and Mrs. James Kerr Love were the dearest of hosts. They did everything possible to make us comfortable and give us pleasure. The cottage, ‘Dalveen’, at West Kilbride, which they provided for us was adorable with climbing roses and a garden which I shall always remember with joy. There was a tremendous bank of broom at one end of it that filled the garden with golden glory. Teacher[2] said it looked as if the sun had fallen out of the sky, it was so bright. The mingled fragrances of sweetbrier, fir, and honeysuckle are heavenly! The hawthorn, golden privet, laurel, and rhododendron hedges were breath-taking. They are three or four feet wide and higher than my head. One could walk on the tops of them, they are so compact. And the mists and rains keep them fresh and scintillating. One can’t complain of rain which produces such magical effects. It actually seems as if it were raining wild-flowers upon the hills and larks in the fields of Scotland! Teacher and Polly went into ecstasies over the birds—blackbirds and thrushes kept them happily awake half the night. We had a dear little Scotch maid, Peggy, who kept house and cooked for us and chased our new ‘Scottie’ when she ran away, which she did eight times in ten days.

This troublesome darling was given Teacher as a birthday present by Mr. Anderson. A friend of his, a dog-fancier in Scotland, brought Ben-sith (pronounced Benshee—means Fairy in Gaelic) to ‘Dalveen’ the day after we arrived, and the chase began then and there. Ben-sith is a wild little elf in fur, and prefers the hills and braes to a civilized dwelling. She isn’t a year old. I’m afraid she’s going to break many dog-hearts in America. Teacher is devoted to her and spends much time every day making her black coat soft and glossy. She intends to give her in marriage to our wee Darky, if they please each other.

HELEN KELLER AMONG THE BROOMAT ‘DALVEEN’

Although I had seen Dr. Love only twice in my life, yet I had the sincerest affection for him. I had read his book, The Deaf Child