Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jazzybee Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

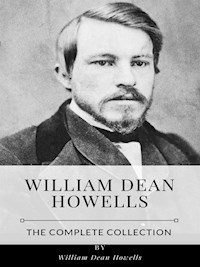

The numerous class of novel readers who for a lifetime have wandered through the fields of fiction, not premeditatedly seeking mental or moral improvement, but with a mind chiefly on "pleasure bent," have a treat in store in 'Heroines of Fiction.' Mr. Howells does not write of his own heroines of fiction — it is the creations of the English and American novelists of times long ago who have filled an imaginative world with a galaxy of feminine loveliness and charm that he considers. The dear old friends of fiction who have become as real to us, in name and appearance, as if we and they had lived side by side in the passing years. Mr. Howells presents them to us again, recalling many endearing traits and captivating graces—looking at them also from the literary standpoint and their special relation to the story to which they belong. Mr. Howells has his favorites among novel writers, and he frankly avows his likings. Jane Austen, George Eliot and Henry James he places on a high pedestal far above their contemporaries. Second only to these is the place he awards to Thomas Hardy and Mrs. Humphry Ward. Beginning with Richardson's "Clarissa Harlowe," he gives us loving and graceful sketches often set in a dramatic scene from the novel under discussion of the heroines of Dickens, Scott, Thackeray, Charlotte Brontë, Charles Reade, and many others.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 758

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Heroines Of Fiction

WILLIAM DEAN HOWELLS

Heroines of Fiction, W. D. Howells

Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck

86450 Altenmünster, Loschberg 9

Deutschland

ISBN: 9783849657710

www.jazzybee-verlag.de

CONTENTS:

SOME NINETEENTH-CENTURY HEROINES IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY 1

FRANCES BURNEY'S EVELINA.. 9

TWO HEROINES OF MARIA EDGEWORTH'S. 16

JANE AUSTEN'S ELIZABETH BENNET.. 25

JANE AUSTEN'S ANNE ELIOT AND CATHARINE MORLAND... 33

JANE AUSTEN'S EMMA WOODHOUSE, MARIANNE DASHWOOD, AND FANNY PRICE 43

HEROINES OF MISS FERRIER, MRS. OPIE, AND MRS. RADCLIFFE.. 52

SCOTT'S REBECCA AND ROWENA, AND LUCY ASHTON... 60

SCOTT'S JEANIE DEANS AND COOPER'S LACK OF HEROINES. 68

A HEROINE OF BULWER'S. 75

THE EARLIER HEROINES OF CHARLES DICKENS. 83

HEROINES OF CHARLES DICKENS'S MIDDLE PERIOD... 90

DICKENS'S LATER HEROINES. 98

HAWTHORNE'S HESTER PRYNNE.. 106

HAWTHORNE'S ZENOBIA AND PRISCILLA, AND MIRIAM AND HILDA 115

THACKERAY'S BAD HEROINES. 125

THACKERAY'S GOOD HEROINES. 133

THACKERAY'S ETHEL NEWCOME AND CHARLOTTE BRONTE'S JANE EYRE 141

THE TWO CATHARINES OF EMILY BRONTE.. 150

CHARLES KINGSLEY'S HYPATIA.. 158

THE NATURE OF CHARLES READE'S HEROINES. 166

VARIATIONS OF READE'S TYPE OF HEROINES. 175

GEORGE ELIOT'S MAGGIE TULLIVER AND HETTY SORREL. 185

GEORGE ELIOT'S ROSAMOND VINCY AND DOROTHEA BROOKE 198

GEORGE ELIOT'S GWENDOLEN HARLETH AND JANET DEMPSTER 207

ANTHONY TROLLOPE'S LILY DALE.. 217

ANTHONY TROLLOPE'S LUCY ROBARTS AND GRISELDA GRANTLY 227

ANTHONY TROLLOPE'S MRS. PROUDIE.. 236

THE HEROINE OF "THE INITIALS". 246

THE HEROINE OF " KATE BEAUMONT". 255

MR. JAMES'S DAISY MILLER.. 263

MR. THOMAS HARDY'S HEROINES. 272

MR. THOMAS HARDY'S BATHSHEBA EVERDENE AND PAULA POWER 282

WILLIAM BLACK'S GERTRUDE WHITE.. 294

MR. BRET HARTE'S MIGGLES, AND MR. T. B. ALDRICH'S MARJORIE DAW 303

MR. G. W. CABLE'S AURORA AND CLOTILDE NANCANOU.. 309

MR. H. B. FULLER'S JANE MARSHALL AND MISS M. E. WILKINS'S JANE FIELD 316

MRS. HUMPHRY WARD'S HEROINES. 326

SOME NINETEENTH-CENTURY HEROINES IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

IN proposing to confine these studies to the nineteenth-century heroines of Anglo-Saxon fiction, I find myself confronted by a certain question, which I should like to share with the reader.

A day, a month, a year, these are natural divisions of time, and must be respected as such; but a century, like a week or a fortnight, is a mere convention of the chronologers, and need not be taken very literally in its claim to be exactly a hundred years long. As to its qualities and characteristics, it had much better not be taken so; and in a study like the present one is by no means bound to date the heroines of nineteenth-century fiction from the close of the eighteenth century, even if the whole world were agreed just when that was. In fact, since the heroines of fiction are of a race so mixed that there is no finding out just where they came from, there is some reason why a study of nineteenth-century heroines should go back to their greatest-grandmothers m the Byzantine romances, or even beyond these, to the yet elder Greek lineages in the "Iliad" and the "Odyssey." But there is still more reason why it should not do anything of the sort. We may amuse ourselves, if we choose, in tracing resemblances and origins; but, after all, the heroines of English and American fiction are of easily distinguishable types, and their evolution in their native Anglo-Saxon environment has been, in no very great lapse of time, singularly uninfluenced from without. They have been responsive at different moments to this ideal and to that, but they have always been English and American; and they have constantly grown more interesting as they have grown more modem.

I

The best thing in the expression of any sort of modernity is a voluntary naturalness, an instructed simplicity; and there is no writer of the present moment, not Mr. Hardy, not Count Tolstoy himself, who is more modern than Defoe in these essentials, though Defoe wrote two hundred and fifty years ago. But we cannot go back to Defoe in this place any more than we could turn, say, to M. Zola. Defoe is distinctly of the nineteenth century in the voluntary naturalness and instructed simplicity of his art, but he is no more of the English nineteenth-century tradition, or principle or superstition, call it what you will, than M. Zola. He wrote the clearest, purest English, the most lifelike English; and his novels are of a self-evident and most convincing fidelity to life. But he was, frankly, of the day before we began to dwell in decencies, before women began to read novels so much that the novel had to change the subject, or so limit its discussion that it came to the same thing. Defoe was of a vastly nobler morality than Fielding, and his books are less corrupting; they are not corrupting at all, in fact; they are as well intentioned as Richardson's, which sometimes deal with experiences far from edifying in order to edify. He is a greater, a more modern artist than either of the others; but because of his matter, and not because of his manner or motive, his heroines must remain under lock and key, and cannot be so much as named in mixed companies. Defoe's novels cannot be freely read and criticized; only his immortal romance is open to all comers, of every age and sex, and it is a thousand pities that " Robinson Crusoe " has no heroine. We must not begin to study our heroines of nineteenth-century fiction with him, though, aesthetically and ethically, nineteenth-century fiction derives from him in some things that are best in it, especially in that voluntary naturalness and instructed simplicity which are the chiefest marks of modernity.

We cannot begin a hundred years later with the heroines of Samuel Richardson, though one of them at least is as freshly modern as any girl of yesterday or tomorrow. Clarissa Harlowe, in spite of her eighteenth-century costume and keeping, remains a masterpiece in the portraiture of that Ever-Womanly which is of all times and places. The form of the novel in which she appears, the epistolary novel, is of all forms the most averse to the apparent unconsciousness so fascinating in a heroine; yet the cunning of Richardson (it was in some things an unrivalled cunning) triumphs over the form and shows us Clarissa with no more of pose than she would confront herself with in the glass. It is in her own words that she gives herself to our knowledge, but we feel that she gives herself truly, and with only the mental reserves that a girl would actually use: there is always some final fact that a girl must withhold.

She gives not herself alone, but all her environment, vividly, credibly, convincingly, in the letters she writes. She persuades us that she lives and suffers; and though it is preposterous in the novelist to study her love-affair so minutely as he does, it is not preposterous but most simple and natural for her to dwell upon it in every detail. It is all the world, the center of the universe to her experience, and however the author permits her to tire the reader, she cannot be supposed to tire herself or tire her ardent friend and correspondent, Miss Anna Howe, in her unstinted outpourings. Indeed, when the reader has once put himself in sympathy with a heroine who does not always deserve it, he too is eager for the smallest particulars of her pathetic fate.

The situation in "Clarissa Harlowe" is one which the author was apparently much more at home in than in the situations of either " Pamela " or " Sir Charles Grandison." Richardson was not native to the low life of the one or the high life of the other, but to the middle-class life where Clarissa Harlowe belongs. There, at ease in the setting, he had merely to imagine an impulsive, affectionate, right-principled girl, persecuted by her philistine family, who try to force her into a hateful marriage, till they drive her to the protection of the lover who plots her ruin. It is very imaginable that when she cannot save herself from him, she should reject the offer of his hand, and that she should die of her griefs; but these are not the vital facts of the case from an artistic point of view. From such a point of view, the heroine's gentle and lovable nature, the characters of the different personages, and the incidents that arise from them and reveal them, are the main matters, and it is here that Richardson has his greatest success. Clarissa is more lifelike in what she does than in what she says, for she has to say too much, though in her spirited resentment of her wrongs from her detestable family, she brings palpably before us her weak mother and father, her hateful sister and brutal brother, and all the abetting cousins and aunts and uncles. Her waverings, however, her hesitations and withdrawals, her resistances and persistences, it is in these that the author most truly finds her and reveals her. As he finds her and reveals her she is like girls of our widely different circumstance in the measure that many great-grandmotherly miniatures are like the photographs of their great-granddaughters. She is, in her character, of the nineteenth century, but in her environment she is almost as impossible as the heroines of Defoe, from whom she derives in the right realistic line.

II

It remained for a still later, but not much later, novelist to portray in the sister-heroines of "The Vicar of Wakefield," two dear girls who are far more appreciable and acceptable to our nineteenth-century notions. They are as distinctly of the eighteenth-century circumstance as Clarissa Harlowe, but they are somehow so transcendently imagined that they have survived into our time with the effect of being born in it.

It can hardly be claimed that Goldsmith was a greater imagination than Richardson; but he was certainly a greater artist. He had the instinct of reticence, which Richardson had not, and it is not going much too far to say that the nineteenth-century English novel, as we understand it now, with its admirable limitations, was invented by Oliver Goldsmith. The novel that respects the right of innocence to pleasure in a true picture of manners, and honors the claim of inexperience to be amused and edified without being abashed, was his creation. He did not know himself, perhaps, how wonderfully he was prophesying, in "The Vicar of Wakefield," the best modern fiction of England and America.

He does not portray the incidents or characters which Richardson studies with a pious abhorrence, or Fielding with a blackguardly sympathy. His realism stops short of the facts which may appall, or which may defile the fancy. It contents itself with the gentle domestic situation of the story and its change from happiness to misery through chances none the less probable because they are operated by the author so much more obviously than they would be now by an author of infinitely less inspiration. Such an artist would not now accumulate disaster upon Dr. Primrose's head so clearly with his own hand; disaster has become much more accustomed to the affliction of fictitious character and makes its approaches with the indirectness and delays noticeable in the actual world. Neither would such an artist have employed means so little psychological as the good man's sudden loss of fortune and his swift precipitation to misery by the wretch who breaks the heart of his daughter, and spoils the joy of all those harmless lives. Happily for the finer art of our time, the betrayer does not now imaginably find his way into the family of a country clergyman with the intent to dishonor and destroy it; but even in the brutal time when such things were justly imaginable the author spares us the worst with a sort of prophetic sensibility. The fair Olivia is, indeed, eloped with if not quite abducted; things could not be otherwise managed in that day without defiance of the traditions alike of fiction and of fact; but she stoops to folly only through a mock marriage, and this in the end, as is well known, proves a real marriage, thanks to the twofold duplicity of the wicked lover's agent, who, for purposes of his own, has had the ceremony performed by a real clergyman. Her tragic fate gives her a sort of dignity not innate in her; and in her potential relenting towards the ultimate disaster of the scoundrel who has so cruelly misused her, she has the highest charm of the Ever-Womanly—at least to the Ever-Manly witness. But it is at no time pretended that she is a wise person, even by the fond father who tells the story of his family. "Olivia, now about eighteen," he says in such antithetical portraiture of his daughters as the age delighted in, " had that luxuriancy of beauty with which painters generally draw Hebe; open, sprightly and commanding. Sophia's features were not so striking at first, but often did more execution; for they were soft, modest and alluring. Olivia wished for many lovers; Sophia to secure one. Olivia was often affected from too great desire to please; Sophia even repressed excellence from her fear to offend. . . . I have often seen them exchange characters for a whole day together. A suit of mourning has transformed my coquette into a prude, and a new set of ribbands has given her younger sister more than natural vivacity."

III

It is a picture that makes one wish the more that the good doctor had carried his complaisance a little farther and told us what color his girls' eyes and hair were of, and which was the taller or slighter. In the absence of positive information one is left to suppose from the internal evidence that Olivia was large and fair, and Sophia of a low stature and a brunette complexion; or the reverse, as one likes. As to their dress, that is not so wholly matter of conjecture, for their father tells us that even after the loss of his fortune, when they were forced to live humbly like their country neighbors, he "still found them attached to their former finery. They still loved laces, ribbands, bugles and catgut; my wife herself retained a passion for her crimson paduasoy. . . . When we were to assemble in the morning at breakfast, down came my wife and daughters dressed out in all their former splendor: their hair plastered up with pomatum, their faces patched to taste, their trains bundled up into a heap behind, and rustling at every motion."

It is well known how the ladies were portrayed in the famous picture of the Primrose family, which, when the wandering limner had finished it out-doors, was found too big to be got into the house. "My wife desired to be represented as Venus, and the painter was requested not to be too frugal of his diamonds in her stomacher and hair. . . . Olivia would be drawn as an Amazon, sitting upon a bank of flowers, dressed in a green joseph, richly laced with gold, and a whip in her hand. Sophia was to be a shepherdess, with as many sheep as the painter could put in for nothing."

The behavior of the ladies was in conformity to the dispositions respectively assigned to them; but all the world has long been too familiar with it to suffer more than one or two illustrative instances. When young Thornhill first presented himself without invitation among them, it is known how coldly they received him, but how, when he refused to be repulsed, they relented, and the girls, at their mother's bidding, played and sang for him. "Mr. Thornhill seemed highly delighted with their performance and choice, and then took up the guitar himself. He played very indifferently; but my eldest daughter repaid his former applause with interest, and assured him that his tones were louder even than those of her master. . . . As soon as he was gone my wife called a council. . . . 'Tell me, Sophia, my dear, what do you think of our new visitor? Don't you think he seemed to be very good-natured?' 'Immensely so, indeed, mamma,' replied she. 'I think he has a great deal to say upon every subject, and is never at a loss; and the more trifling the subject the more he has to say.' 'Yes,' cried Olivia, 'he is well enough for a man, but for my part I don't much like him, he is so extremely impudent and familiar; but on the guitar he is shocking.' "

It is of course in keeping with her character that this mother meets her hapless daughter with cruel upbraiding when she comes back to her ruined home, but wholly forgives her in the end when she finds that Olivia has been incontestably "made an honest woman of" by the machinations of her betrayer's betrayer. Mrs. Primrose, however, is by no means a harsh nature, even if she is a woman so little wiser than some men. She is always a most acceptable presence in the story, and never more so than when she is most foolish. She is very modern in being of the illogical and inconsequent type of her sex which fiction has rather over-delighted in painting since her day. Probably there were hints of her in fiction from the very beginning, but it was Goldsmith who first painted one of the many ancestresses of Mrs. Nickleby in full length. She reasons from her wishes and believes from her hopes, with those vast leaps from premises to conclusions which we have all witnessed in ladies of her mental make, both in and out of novels. She prevails by the qualities of her heart, and her adequacy to most domestic occasions shows that the home may be governed with as little wisdom as the world. She influences the sage Sophia as strongly as the giddy Olivia, and it is pleasant to see how she is held in her motherly supremacy by the affection of her children, and the love of her husband, who perfectly understands her. In fact, a very pretty case might be made out of her as the real heroine of the book.

She and Olivia are both of much more readily perceptible quality than Sophia. One expects Olivia to do what she does; it is almost inevitable; and then one expects an interval of good sense in her after her misfortunes, which, it is intimated, have chastened without essentially changing her. Sophia is a more difficult nature to deal with, for her charm has to be shown in negative ways. She has a great deal more mind than either her mother or sister, but she is mostly subject to them, and follows their lead as younger daughters and sisters do, or at least used to do. She will practically share in many of Olivia's absurdities in spite of her greater light and knowledge, and she is preserved from her disasters apparently by a fate that does not always befriend passive principle. It is just in her passivity, however, that she is so dear to the heart, so like so many other nice girls who are often so much wiser than anything they do, or even say. One of Mr. Thomas Hardy's heroines is reported to have been able to converse like a philosopher, but to be apt, in emergency, to behave like a robin in a greenhouse. If this was not quite the case with Sophia, it must be owned that her main superiority to Olivia was shown in her being fallen in love with by a better man, and in her refusing to be carried off by the villain who had deceived her sister; though it ought to be said in Olivia's behalf that it is much easier to resist being carried off against your will than with it.

IV

It was the age of moral sentiments, and to have them at hand was the sovereignest thing against temptation from without and within. Heroines used to express them whenever the least danger threatened, and sometimes when they were in perfect safety. Under instruction of the good Samuel Richardson they sought the welfare of themselves, their lovers, and their correspondents in formularies prescribing the virtues for every exigency, and praising right conduct with a constancy which ought to have availed rather more promptly than it did. But neither of the girls in "The Vicar of Wakefield" is very profuse of them, and this marks either a lapsing faith in their efficacy, or a rising art in the novelist. Goldsmith, at any rate, confines the precepts and reflections to the father of his heroines, as he might fitly do in the case of the supposed narrator; Richardson, or rather the epistolary form of his novels, obliges his heroines to make them. Yet he was a great master, and, in spite of his preaching, a great artist. He was a man of a mighty middle-class conscience, and in an age not so corrupt as some former ages, but still of abominable social usages, he could not withhold the protest of a righteous soul, though he risked rendering a little tedious the interesting girls who uttered it for him.

He was blamed for portraying facts which were not so edifying as the morals to be drawn from them; and this may have been why he made his heroines so didactic. Somehow he had to trim the balance, and if the faithful portraiture of vice involved danger of contamination to the reader, virtue must be the more explicit and prodigal of its prophylactics and antidotes. His excess in both directions was corrected by the wiser art if not the purer instinct of the group of great women novelists who inherited his moral ideals and refined upon his materials and methods. Society had perhaps not grown much less licentious when Fanny Burney and Maria Edgeworth and Jane Austen began to write, but it was growing less openly licentious, and it might be studied in pictures less alarming to propriety, if not to innocence.

These women, who fixed the ideal of the Anglo-Saxon heroines, wrote at the close of the last century and the beginning of this, some thirty years after the masterpieces of Richardson appeared, and fifteen or twenty years after "The Vicar of Wakefield" imparted to all Europe the conception of a more exquisite fiction. In some sort Richardson served them as a model, and Goldsmith as an inspiration, but it was they who characterized the modern Anglo-Saxon novel which these masters had perhaps invented. The most beautiful, the most consoling of all the arts owes its universal acceptance among us, its opportunity of pleasing and helping readers of every age and sex, to this group of high-souled women. They forever dedicated it to decency; as women they were faithful to their charge of the chaste mind; and as artists they taught the reading world to be in love with the sort of heroines who knew how not only to win the wandering hearts of men, hut to keep their homes pure and inviolable. They imagined the heroine who was above all a Nice Girl; who still remains the ideal of our fiction; to whom it returns with a final constancy, after whatever aberration; so that probably if a composite photograph of the best heroines of our day could be made, it would look so much like a composite miniature of their great-great-grandmothers in the novels of these authors that the two could not well be told apart.

FRANCES BURNEY'S EVELINA

THE author and the heroine of "Evelina" can never be quite separable in the fancy of the reader who studies the characters of both in the stories of their lives, though their lives themselves were so very different; and the happiness that came to the heroine so dramatically and so decisively was so long a time on its way to the author.

I

"Evelina" was published in 1788 and made its instant success; a few years later, her sister - heroine " Cecilia " appeared in the novel of that name, and yet a few years later the brilliant young author was tempted from her charming home, the fond circle of her friends such as Johnson, Burke and Reynolds, the public that idolized her, to become the waiting-woman of the commonplace queen of George III. It was an error so cruel that it hurts one yet to think of it; one rages against it as if it were still actual, and is not consoled by the fact that the victim never thoroughly realized her suffering as wrong to literature. It spoiled her career, and broke her health, but she seems to have thought to the last that her slavery was an honor; and she was prouder of the kindness which her devotion had inspired even in the heart of royalty, than of anything else in her history. When after five years she left the grudging queen's service, her father, who had urged her to enter it, could never understand why she wished to leave it. He indeed welcomed her back to her home and her broken literary life, and many years later she began to write novels again; but the simplicity, the girlish spirit, the young grace was gone from her work, and " Camilla " and "The Wanderer" are conscious, academic poses of a talent once so spontaneous. It was a talent once so spontaneous, so vivid, so unaffected, that when Fanny Burney first had before her the task of depicting the nature and behavior of "A Young Lady on her Entrance in the World," she looked in her glass for her model, and wrought with the naivete of the true artist, especially the true artist who is also young.

It is not to be supposed that she purposely drew herself in Evelina Anville. That is not the way of good art, though the end, the effect is self-portraiture. It is essential to the charm of a fictitious character that he or she who makes it in his or her image should not be aware of doing so; and no doubt Miss Burney kept well within her illusions. If she had perfectly known what she was doing, there would have been touches of self-defense, of self-flattery in Evelina which would have spoiled our pleasure in her; but probably there were people who knew who Evelina was at the time, if Miss Burney did not, and had not to wait nearly fifty years for the "Diary and Letters of Mine. D'Arblay" to let them into the open secret. The great Dr. Johnson knew it, and if he did not declare it, he came little short of it in his recognition of her admirable and endearing qualities. The great Mr. Burke must have known it, and all that famous and friendly company which resorted to her father's house when the timid and gentle girl suddenly astonished them by proving herself a novelist hitherto unrivalled in a certain charm and truth.

II

Before "The Vicar of Wakefield" there had been no English fiction in which the loveliness of family life had made itself felt; before Evelina the heart of girlhood had never been so fully opened in literature. There had been girls and girls, but none in whom the traits and actions of the girls familiar to their fathers, brothers and lovers were so fully recognized; and the contemporaneity instantly felt in Evelina has lasted to this day. The changes since her entrance into the world have been so tremendous that we might almost as well be living in another planet, for all that is left of the world she so trembled at and rejoiced in. But whoever opens the book of her adventures, finds himself in that vanished society with her, because she is herself so living that she makes everything about her alive.

She is of course imagined upon terms of the romantic singularity which we no longer require in letting a nice girl have our hearts. Her father is of a species so very hard-hearted as to be extinct now, even in the theatre. He denies his marriage with her mother, and destroys the proof of it for no very apparent motive (he seems to have been very much in love with his wife), except to equip his daughter with a mystery and an unnatural parent for purposes of fiction. He retires into the background of the story before Evelina is born, and does not emerge from it until he is needed to be forgiven at the end, when he bestows her hand upon the hero with proper authority. In the meantime she has been brought up in great seclusion by the Rev. Arthur Villars, a friend of her mother's father, who has devoted himself to her education, and has cherished her as if she were his own child. It is solely to him that her fondest thoughts and affections turn when at the age of seventeen she leaves Berry Hill with his approval and launches upon the gay world of London in the care of certain friends of his.

It duly appears that, besides the exceptionally ruthless father who will have nothing to do with her, Evelina has a very terrible grandmother, who was an English servant when her beauty caught the young fancy of Evelina's grandfather. He expiates his passion by many years of marriage with her in France, and after his death she returns in a second widowhood to London, just at the moment Evelina is entering the fashionable world there, and becomes the low comedy and low tragedy of the story. She is not only very awful herself, with a French bourgeois vulgarity thickly overlaying her English servile vulgarity, but she is surrounded by Evelina's city cousins, who have a cockney vulgarity all their own, and for whom she claims the girl's affection, together with her duty to herself. They complicate the poor child's relations with the finer world to which she belongs by instinct and breeding, in all sorts of ways; and if anything could prevent her predestined union with the exemplary Lord Orville, their behavior would do it. She is horribly ashamed of them, but she does nothing cruel to escape them, and she submits to her grandmother not only because she must, but because she will. In short, at the moment when snobbery was first coming to its consciousness in literature Evelina was not a snob. She otherwise shows herself a thoroughly good girl, and she does it charmingly, though she has to do it without seeming to do so, in the long letters which she writes relating her adventures and which, with those of her correspondents, form the old-fashioned vehicle of the story.

III

Her letters are mostly addressed to the admirable, the almost too admirable, Mr. Villars, who replies to her abounding confidences with sympathy and wisdom from his seclusion at Berry Hill. In an age of unfeeling fathers his tenderness is more than paternal, but except that the story would have had to stop if he had done so, there seem times when he might have usefully given her a little more paternal protection. He has armed her against fate merely with a variety of high principles, and Evelina herself has to own that she is never in trouble when she is true to them. She learns very early the difference between meaning to behave always in perfect conformity to them and really doing so, for at her very first ball she refuses to dance with a fop she does not like, and, forgetting she has told him she is not dancing at all, she dances with Lord Orville, whom she does like from the moment she sees him. Worse than this, she cannot help laughing at the beau's grotesque indignation with her innocent perfidy; and at the very next ball she has profited so little by her experience that she again falls a prey to her own rather ingenuous duplicity. Lord Orville did not come to ask her for the first dance, as she hoped he might; but " a very fashionable, gay-looking man, who seemed about thirty years of age, . . . begged the honor." Her chaperon, from whom she had become separated, had told her "it was highly improper for a young woman to dance with strangers at any public assembly," and not wishing to risk the sort of offence she had given at her first ball, she answers this gentleman that she is engaged already. "I meant," she writes to Mr. Villars, and she owns that she blushes to write it, " to keep myself at liberty to dance or not, as matters should fall out. . . . He looked at me as if incredulous . . . asked me a thousand questions, and at last he said: ' Is it really possible a man whom you have honored with your acceptance can fail to be on hand? You are missing the most delightful dance in the world. . . . Will you give me leave to seek him? . . . Pray, what coat has he on? . . . My indignation is so great that I long to kick the fellow round the room.'" In vain she tries to escape her lively tormentor; to her shame and confusion he attaches himself to her and leads the way through the rooms, entreating her to let him find her recreant partner. "'Is that he?' pointing to an old man who was lame, 'or that?' And in this manner he asked me of whoever was old or ugly in the room." She frankly tells him at last that he has spoiled all her happiness for the whole evening, but he will not leave amusing himself with her distress till she feigns at sight of Lord Orville that it is he whom she was to dance with. She does no more than glance at his lordship, but that is quite enough for her persecutor. " His eyes instantly followed mine. 'Why, is that the gentleman?' ... At this instant Mrs. Mirvan, followed by Lord Orville, walked up to us, . . . when this strange man, destined to be the scourge of my artifice, exclaimed, 'Ha, my Lord Orville!—I protest I did not know your lordship. What can I say for my usurpation? Yet, faith, my Lord, such a prize should not be neglected!' My shame and confusion were unspeakable. Who could have supposed or foreseen that this man knew Lord Orville? But falsehood is not more unjustifiable than unsafe! Lord Orville—well he might—looked all amazement. ' The philosophic coldness of your lordship,' continued this odious creature, 'every man is not endowed with.' . . . He suddenly seized my hand, saying, ' Think, my Lord, what must be my reluctance to resign this fair hand to your lordship!' In the same instant Lord Orville took it of him. . . .To compel him then to dance I could not endure, and eagerly called out, ' By no means—not for the world! I must beg—' 'Will you honor me with your commands, madam?' cried my tormentor. . . . 'But do you dance or not? You see his lord-hip waits!' . . . 'For Heaven's sake, my dear', cried Mrs. Mirvan, who could no longer contain her surprise, 'what does all this mean? Were you pre-engaged? Had Lord Orville—' 'No, madam,' cried L only—only I did not know this gentleman—and so I thought—I intended—I—' ... I had not strength to make my mortifying explanation; my spirits quite failed me, and I burst into tears. They all seemed shocked and amazed. . . . 'What have I done? exclaimed my evil genius, and ran officiously for a glass of water. However, a hint was sufficient for Lord Orville, who comprehended all I would have explained. He immediately led me to a seat, and said to me in a very low voice, 'Be not distressed, I beseech you; I shall ever think my name honored by your making use of it. ' "

IV

The scene in the ballroom, where Evelina becomes the prey of the tease whom she has not meant to deceive harmfully, is one of many in which Sir Clement Willoughby pursues and torments her. He begins by teasing her, and ends by loving her, but he never imagines marrying her. That is reserved for Lord Orville, who thought her rather a poor thing at first, but comes more and more to feel her charm and realize her worth. She has not an instant's misgiving as to him. From the earliest moment she finds his "conversation really delightful. His manners are so elegant and so gentle, so unassuming that they engage esteem and diffuse complacence," quite as they would with Dr. Johnson, in whose diction Miss Burney upon this occasion speaks for her heroine. But in fact Lord Orville is a gentleman and not a prig, at a time when the choice between being a prig and being a blackguard was difficult for a young man in good society. It has been rather the custom of criticism to decry this hero, but he never shows himself unequal to his great office of appreciating Evelina. No matter what box she is m he divines that she got there for some reason that was honorable to her heart if not to her head.

It is with a fine courage that Miss Burney shows her heroine in her silliness as well as her sense, but she can do this without that suspicion of satirizing her sex which would attach to a writer of the other sex. In fact, one great charm of the story is that it is not satire at all. It is mostly light comedy; it is sometimes low comedy; it is at other times serious melodrama; but the lesson from it is never barbed, and the author's attitude towards her characters has never that sarcastic knowingness which has been the most odious vice of English novelists.

V

It was an age when in a lady's house, and almost in the presence of the man who loves her, a young girl could be pursued by the impudent addresses of men who thought her too poor and too humble for marriage. This is Evelina's fate, which she thinks hard, but does not seem to think exceptional; though she is at least preserved from being carried off by such a man. She is indeed inveigled from her friends at the opera by Sir Clement Willoughby, who had known her only as a gentleman might know a young lady in society nowadays, and hurried into his chariot (it looks like a coupé in the old pictures), to be driven anywhere but to her chaperon's address. She saves herself by putting her head out of the window and screaming; then he drives home with her; but the incident does not seem to put an end to their acquaintance, or even to his professions of love. Nothing does that but her engagement to Lord Orville, who, till he asks her to marry him, could not have seen anything so very monstrous in Sir Clement Willoughby's behavior, though he would himself have been incapable of it.

The elopement as a popular means of moving the reader flourished much longer in fiction; but apparently the abduction, which had been so frequently and so effectively employed, was already going out; and in Evelina we find it reduced to such a poor attempt as Sir Clement Willoughby's. It was perhaps going out in society, but it would not be safe to say it had gone out. Probably in the last decades of the century, an heiress would not, even in Ireland, be attacked by her cousin in her uncle's presence, and carried off shrieking, with her clothes half torn from her person, to be tied hand and foot and bound upon a horse behind her captor; or, when she had flung herself to the ground and got possession of a sword for her defense, would be savagely stabbed by one of the abducting party, and then buried to her chin in a bog to hide her from the pursuit of her rescuers. But all this happened about 1745 to Miss Macdermot, who saved herself from a forced marriage with her abductor by catching a pipkin of hot milk from the fire and flinging it into the face of the officiating priest.

Horace Walpole sneered, and probably with reason, at Richardson's novels as pictures of English high life. The old printer, who once had all Europe thrilling over his pages, must have made many minor mistakes as to the diction and deportment of people of fashion; but doubtless he knew his times very well, and would not go astray in the particulars of an abduction, even an abduction in high life.

In few of the novels before " Evelina " could the reader help being privy to some such high-handed outrage. All over England heroines were carried off in chairs and chariots to lonely country houses, there to be kept at the mercy of their captors till the exigencies of the plot forced their release. It must have been a startling innovation that Evelina should be let off so easily as she was, but even this was not so strange as that in an age of epistolary fiction she should be allowed to portray in herself that character of a bewitching goose that she really was, and that her author should effect this without apparent knowingness, or any manner of wink to the reader. Evelina is a masterpiece, and she could not be spared from the group of great and real heroines. The means of realizing her are now as quaint and obsolete almost as the manners of the outdated world to which she was born. Nobody writes novels in letters anymore; just as people no longer call each other Sir and Madam, and are favored and obliged and commanded upon every slight occasion; just as young ladies no longer cry out, when strongly moved, "Good God, sir," in writing to their reverend guardians; or receive prodigious compliments; or make set speeches, or have verses to them posted in public places; or go to amusements where they are likely to be confused with dubious characters. Evelina is forced to see and to suffer things now scarcely credible, and it is her business in the long letters she writes her foster-father to depict scenes of vulgarity among her city cousins which make the reader shudder and creep. She depicts other scenes among people of fashion which are not less vulgar, and are far crueler, like that where two gentlemen of rank have two poor old women run a race upon a wager and push the hapless creatures on to the contest with cheers and curses. A whole world of extinct characters and customs centers around her; but she outlives them all in the inextinguishable ingenuousness of a girlish mind which nothing pollutes, and in the purity of a nature to which everything coarse and unkind is alien. She is tempted at times to laugh at things that other people think funny, but she seems a little finer even than her inventor in all this, and it appears less Evelina than Miss Burney who expects you to enjoy the savage comedy of Captain Mervin's insulting pranks at the expense of Madame Duval. In fine, Evelina, though a goose, is perhaps the sweetest and dearest goose in all fiction. We laugh at her (we must not forget that it is she herself who lets us laugh at her), but we love her, and we rejoice in the happiness which she finds so supernally satisfying, as she passes out of the story, panting with rapturous expectation of bliss in keeping of Lord Orville.

TWO HEROINES OF MARIA EDGEWORTH'S

FEW figures in literary history appeal to the remembrance so pathetically as the author of " Evelina." She had many trials which she bore with sweetness and patience; her blessings were mainly from her gift of being content with little, and of overprizing any kindness people did her, as if it were the effect of extraordinary virtue in them. Indeed, Fanny Burney was Evelina. She had not only written herself into the character of that heroine, but she had so thoroughly written herself out in it, that she seemed not to have had the stuff for another heroine left in her nature. Or, if this is going too far, it is certain that neither Cecilia nor Camilla makes herself remembered like Evelina as a real personality.

I

" Cecilia " was written while the author of " Evelina " was still Miss Burney, and before she entered the service of the Queen; " Camilla " was written long after she had left that service, and was published after she had become the wife of the émigré noble D'Arblay. In " Cecilia" she was not yet so overweighted by the fear and favor of the great Dr. Johnson that she wished to write her novels as he would have written them, and the language, if not quite the language of life, is often easy, gay, and natural. The mighty lexicographer was not to do his worst with her diction till many years later in " Camilla, where he prevailed with an effect which the image of a fawn advancing with the gait of a hippopotamus feebly suggests, though in more vital things "Camilla" is far from a mistaken performance. All three of the Burney- D'Arblay novels are on the same ground. They have mainly to do with the London of rank and fashion, and the London of trade and vulgarity; but a good part of the action passes in the country, and another good part in the several English spas whose waters were then the mode, and whose pump-rooms are the scenes of so much love-making in contemporary fiction. But in both " Cecilia " and " Camilla," the nominal heroines are of a less engaging, a less amusing quality. Cecilia is a girl of much more sense than Evelina; she has wit and she has beauty; and yet somehow she fails to take the heart as Evelina does. She moves in a world much more ascertained in its characteristics, through a much more ingenious intrigue. A cloud of genteel company at a dozen different places is suggested; vivid and amusing figures swarm in the pages of the novel. There are, indeed, only too many of them for remembrance, though probably no one who has met such a type of " agreeable rattle" as Miss Lerolle will have quite forgotten her; or her anti-type of supercilious passivity, Miss Leeson. That Lady Honoria who likes getting her father angry because he makes such funny faces and swears so divertingly when he is in a temper, is perhaps not so justifiably dear to the fancy; but she outlives most of the serious personages in the reader's remembrance. In the handling of all, a sense of the author's maturing art grows upon the critic; and in fact the "Cecilia" as a novel is as much superior to the "Evelina" which preceded it as it is to the " Camilla ''which followed it.

II

It is always possible, of course, that " Evelina " might have eventuated in "Camilla," even if the author had not spent five or six years, as the Queen's tire-woman, in the narcotic neighborhood of royalty. The tendency which Richardson had given to the best English fiction, and which is so strongly felt in " The Vicar of Wakefield," might have persisted in Fanny Burney's novels, and overweighted them at last, though she had remained in the world of literature, and looked on uninterruptedly at the world of fashion. Society was then so bad, not in its standards, but in its indifference to them, that all decent writers had it on their consciences to better it to their utmost by the force of imaginary examples. Fiction had not yet conceived of the supreme ethics which consist in portraying life truly and letting the lesson take care of itself. After a hundred years this conception is not yet very clear to many novelists, or, what is worse, to their critics; and the novel, to save itself alive from the contempt and abhorrence in which the most of good people once held it, had to be good in the fashion of the sermon rather than in the fashion of the drama. It felt its way slowly and painfully by heavy sloughs of didacticism and through dreary tracts of moral sentiment to the standing it now has, and we ought to look back at its flounderings, not with wonder that it floundered so long, but that it ever arrived. In fact, it did not flounder so very long, and it arrived at what is still almost an ideal perfection in the art of Jane Austen. But first it had to pass through the school of Maria Edgeworth, who was as severe a disciplinarian as ever the lighter-minded muses came under. They have long since had their revenge, poor things, and she has had to pay for her severity in the popular superstition which still prevails that she was all precept, all principle, all preaching. Nothing could be more mistaken, as anyone may prove who will turn to her entertaining novels of English fashionable life, her faithful and sympathetic sketches of Irish character, high and low. It is known that Turgenev, from his pleasure in her Irish stories, conceived the notion of making like studies of Russian conditions; that to this influence the world owes the "Notes of a Sportsman,'' and that the Russian serfs, from the influence of that book with the Czar, finally owed their emancipation.

Fame could have brought Maria Edgeworth's noble spirit no sweeter consolation than such an event; she would have counted such an indirect effect of her work infinitely beyond the inspiration of such a consummate artist as Turgenev, but her long life ended just before our century had reached its fiftieth year, and thirty years before the serfs were freed. She began author well back in the eighteenth century, but she began novelist distinctly within the nineteenth. As her "Castle Rackrent " appeared in 1801, there can be no dispute concerning this fact; and no one who will read that capital story, or almost any other novel of hers, can question her right to stand with the foremost in nineteenth-century fiction by virtue of many things besides her priority in time. Such a reader will feel it his privilege, his highest pleasure, to help reverse the sentence which relegates this artist to the sad society of the mere sermoners. She did preach, there is no denying that, but she also pictured life so faithfully that Scott could wish for nothing greater than " Miss Edgeworth's wonderful power of vivifying all her persons, and making them live as beings in your mind."

She knew her Ireland closely, lovingly, humorously, down to the last whimsicality of the tatterdemalion peasantry and the last eccentricity of the reckless, jovial gentry; but she knew her England, too, and the scenes of London fashion in her books are as graphic as Fanny Burney's. Indeed, it cannot be said that those London stories which have Ireland for a background are better than those which deal solely with English interests and characters. " The Absentee " and its kind are of inferior aesthetic quality, for in these the author has a moral to enforce, a social principle to preach; and in the others she has only character to paint, and personal conduct to portray. For this reason such a novel as " Belinda " is a better test of her powers than " The Absentee." After all, there is no situation so universally appealing to the sympathy and the fancy as that which Miss Burney chose in "Evelina" and "Cecilia," and which Miss Edgeworth again chose in "Belinda." A young girl gently bred, and coming up for the first time from the country to view the world of London society with innocent, astonished eyes—what could be sweeter, more suggestive, more abundant in exciting chance than this?

III

Belinda Portman is no such ingenue as Evelina; she is of a far more sophisticated good sense even than Cecilia, whose more reasoned and tempered innocence she rather partakes. She has a very worldly-minded Mrs. Selina Stanhope for her aunt, who at Bath arranges her invitation for a London season from Lady Delacour, and supplies her with a store of mundane maxims, such as Mrs. Stanhope had found effectual in managing the matrimonial campaigns of five other nieces. The first interesting quality in Belinda is that she has not the wish to profit by this dark wisdom of Mrs. Stanhope's; but early in her London career a mortifying accident acquaints her with the fact that she is supposed to be there to further these matchmaking schemes of her aunt. She is already in love with one of the young men she hears talking her over, and with the hurt to her girlish dignity and delicacy, she begins to think and to reflect. From that hour her evolution into a woman of good sense and good-will, of magnanimous impulses and generous actions is probably and entertainingly accomplished by the author, with unfailing confidence in an apparently inexhaustible knowledge of the London world.

What this world was, how dissipated, unprincipled, brutal, reckless, steeped in debt and drink, has never been more frankly shown. The moral is always present in the picture, and it is too often applied with inartistic directness, but it is not always so applied. There are abundant moments of pure drama, when the character is expressed in the action; and though much of the motive that ought to be seen is stated, still enough of it is seen to constitute the story a work of art. The author proves herself in all her books an aesthetic force; she was perverted in her artistic instincts by false ideals of duty; but she knew human nature, and when she would allow herself to do so she could represent life with masterly power. She does not get Belinda fully before the reader without many needless devices to deepen the intrigue, and many tiresome lectures to enforce the lesson, but she does give at last the full sense of a beautiful girl who gains rather than loses in delightfulness by growing wiser and better. Discreet Belinda has always been, but at first, she is discreet for herself only; and at last she is wise for others as well. A fair half of the book might be thrown away with the effect of twice enriching what was left; perhaps two-thirds might be parted with to advantage; certainly all that does not relate to Belinda's friendship with Lady Delacour and her love for Clarence Harvey would not be missed by the reader who likes art better than artifice, and prefers to make his own applications of the facts. The friendship between Belinda and Lady Delacour is more important than the love between Belinda and Clarence; but if the story were reduced to the truly wonderful study of Lady Delacour's passionate and distorted nature, she and not Belinda would be the heroine of " Belinda.'' As it is, it is she who has the greater fascination for the experienced witness, and for any student of womanhood the dramatic portrayal of her jealousy must appeal as a masterpiece almost unique in that sort.

IV

The domestic situation in Lady Delacour's household is promptly developed through the mysterious contradictions that cloud her conduct: the wild gayety, the listless melancholy, the moody despair. "For some days after Belinda's arrival in town she heard nothing of Lord Delacour; his lady never mentioned his name except once accidentally, as she was showing Miss Portman the house. . . . The first time Belinda ever saw his Lordship, he was dead drunk in the arms of two footmen who were carrying him up-stairs to his bedroom; his lady, who was just returned from Ranelagh, passed him by on the landing-place with a look of sovereign contempt. 'What is the matter? Who is this?' said Belinda. 'Only the body of Lord Delacour,' said her ladyship. . . . 'Don't look so shocked and amazed, Belinda; don't look so new, child; this funeral of my lord's intellects is to me a nightly, or,' added her ladyship, looking at her watch and yawning, ' I believe I should say, a daily ceremony—six o'clock, I protest!' The next morning . . . after a very late breakfast. Lord Delacour entered the room. ' Lord Delacour, sober, my dear,' said her ladyship to Miss Portman, by way of introducing him."

The cat-and-dog life which this couple lead is very unreservedly portrayed, and Belinda is so far deceived as not to suppose that they can be in love with each other, in spite of all. My lord's days and nights are given to debauchery, his lady's to the wildest dissipation at balls and routs (one faintly imagines what a rout was!) and gay parties at those public resorts which were once so much the fashion in London, or at least in London novels, where from Vauxhall to Ranelagh, from Ranelagh to the Pantheon, from the Pantheon to Almack's, there is a perpetual glitter of their misleading lights.

On leaving the masquerade where Belinda has overheard that killing talk about herself among the young men of her circle, she repeats it in an anguish of shame to her friend, as they drive away from Lady Singleton's to the Pantheon, in their respective disguises of the tragic and the comic muse. '"And is this all?' cried Lady Delacour. ' Lord, my dear, you must either give up living in the world or expect to hear yourself, and your aunts, and your cousins, and your friends, from generation to generation, abused every hour in the day by their friends and your friends; 'tis the common course of things. Now you know what a multitude of obedient servants, dear creatures, and very sincere and most affectionate friends I have. ... Do you think I'm fool enough to imagine that they would care the hundredth part of a straw if I were this minute thrown into the Red or the Black Sea?' . . . The carriage stopped at the Pantheon. ... To Belinda the night appeared long and dull; the commonplace wit of chimneysweepers and gypsies; the antics of harlequins; the graces of flower-girls and Cleopatras had not power to amuse her; for her thoughts still recurred to that conversation which had given her so much pain. . . . 'How happy you are, Lady Delacour,' said she, when they got into the carriage to go home, . . . 'to have such an amazing flow of spirits!' 'Amazing you might well say, if you knew all,' said Lady Delacour, and she heaved a deep sigh, threw herself back in the carriage, let fall her mask, and was silent. It was broad daylight, and Belinda had a full view of her countenance, which was a picture of despair. . . . Her ladyship started up and exclaimed, 'If I had served myself with half the zeal I have served the world I should not now be thus forsaken. . . . But it is all over now. I am dying.' . . . Belinda . . . gazed at Lady Delacour, and repeated the word, ' Dying!' ' I tell you I am dying,' said her ladyship."

At home she bade Belinda " follow her to her dressing room. . . . Come in; what is it you are afraid of?' said she. Belinda went in, and Lady Delacour shut and locked the door. There was no light except what came from the candle which Lady Delacour held in her hand. . . . Belinda, as she looked around, saw nothing but a confusion of linen rags; vials, some empty, some full, and she perceived there was a strong smell of medicines. Lady Delacour . . . looked from side to side of the room without seeming to know what she was in search of. She then, in a species of fury, wiped the paint from her face, and returning to Belinda, held the candle so as to throw the light full on her livid features . . . which formed a horrid contrast with her gay, fantastic dress. 'You are shocked, Belinda,' said she, ' but as yet you have seen nothing— look here'—baring half her bosom. . . . Belinda sunk back into a chair; Lady Delacour flung herself on her knees before her. ' Am I humbled, am I wretched enough?"'

The story of Belinda's friendship for the miserable woman from this moment on is imagined with a knowledge of human nature and a divination of its nobler possibilities worthy of Tolstoy, though it is wrought with an art indefinitely more fallible. Miss Edgeworth was not only in herself very inconstantly an artist, but, as is well known, she subordinated her judgment to that of her honored father, whom she allowed to meddle with her work, and mar it in the cause of good morals as much as he would. It is but fair to lay to the charge of her well-willing, ill-witting parent at least half of the crude and clumsy didacticism with which Belinda's fine nature is unfolded in her efforts to serve and to save Lady Delacour; but perhaps the crude and clumsy mechanism of the affair is all Miss Edgeworth's own. We may easily grant this, and still in the dramatic moments find enough evidence of her power to prove her a great artist.

Lady Delacour, of course, believes that she has a cancer, and she has put herself in the hands of a quack who preys upon her fears. Her secret is known only to her waiting-woman, till she herself betrays it to Belinda, whom she binds to her by the most solemn vows of silence. But the girl can find no peace till she has got Lady Delacour's leave to speak of it to a physician (who is, of course, Edgeworthianly over-wise and over-good); and as Belinda has not lived for several weeks under the roof of Lord Delacour without surprising in him some traits of kindness for his wife, she wins Lady Delacour's consent to let him know that some great calamity is threatening her. Belinda sets herself with all her innate discreetness to make them friends, but she does not, discreet as she is, manage this without rousing the jealousy of Lady Delacour, which finds food in her returning love for her husband. Seeing Belinda and Lord Delacour on such increasingly good terms in her interest, she can only believe that they wish to be on better in their own as soon as she is out of the way. As the story was always to end well, however, the cancer proves no cancer, and is cured with very slight scientific attention; Lady Delacour is reconciled to her husband without losing her friend, and Belinda is duly married to Clarence Harvey, whom she has been in love with from the beginning.

Such a meagre résumé of merely one order of its events does no justice to the many-sided interest of the novel, and its rich abundance of characterization, which sometimes accuses itself of caricature, but which probably embodies a presentation of fashionable life at the beginning of our century faithfuller than it can now appear. Still, the jealousy of Lady Delacour, though but one interest of the story, becomes in its finer artistic treatment the chief interest; and the scene in which it betrays itself becomes the greatest moment of the drama. The episode is almost altogether admirable, but its climax sufficiently suggests the whole encounter between the unsuspecting Belinda and Lady Delacour, when her passion is fired by the girl's suppression of certain passages in a letter from her aunt Stanhope, giving some worldly advice which her ladyship ironically congratulates Belinda upon not needing.