17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: E-BOOKARAMA

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

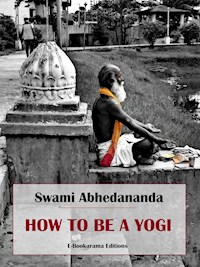

"How to be a Yogi" (1902) is an essential treatise on the various forms of yoga, including Hatha, Raja, Karma, Bhakti, and Jnana; a road-map of the Yogic schools. The book also has chapters on the science of breathing, and the possibility that Christ was a Yogi.

The author:

Swami Abhedananda (2 October 1866 – 8 September 1939), born

Kaliprasad Chandra was a direct disciple of the 19th century mystic Ramakrishna Paramahansa and the founder of Ramakrishna Vedanta Math. Swami Vivekananda sent him to the West to head the Vedanta Society of New York in 1897, and spread the message of Vedanta, a theme on which he authored several books through his life, and subsequently founded the Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and Darjeeling. (

Source: wikipedia.org)

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Swami Abhedananda

How to be a Yogi

Table of contents

HOW TO BE A YOGI

Preface

Introductory

What Is Yoga?

Hatha Yoga

Râja Yoga

Karma Yoga

Bhakti Yoga

Jnâna Yoga

Science Of Breathing

Was Christ A Yogi?

HOW TO BE A YOGI

Swami Abhedananda

Preface

THE Vedânta Philosophy includes the different branches of the Science of Yoga. Four of these have already been treated at length by the Swâmi Vivekananda in his works on "Râja Yoga," "Karma Yoga," "Bhakti Yoga," and "Jnâna Yoga"; but there existed no short and consecutive survey of the science as a whole. It is to meet this need that the present volume has been written. In an introductory chapter are set forth the true province of religion and the full significance of the word "spirituality" as it is understood in India. Next follows a comprehensive definition of the term "Yoga," with short chapters on each of the five paths to which it is applied, and their respective practices. An exhaustive exposition of the Science of Breathing and its bearing on the highest spiritual development shows the fundamental physiological principles on which the whole training of Yoga is based; while a concluding chapter, under the title "Was Christ a Yogi?" makes plain the direct relation existing between the lofty teachings of Vedânta and the religious faiths of the West. An effort has been made, so far as possible, to keep the text free from technical and Sanskrit terms; and the work should therefore prove of equal value to the student of Oriental thought and to the general reader as yet unfamiliar with this, one of the greatest philosophical systems of the world.

THE EDITOR.

Introductory

TRUE religion is extremely practical; it is, indeed, based entirely upon practice, and not upon theory or speculation of any kind, for religion begins only where theory ends. Its object is to mould the character, unfold the divine nature of the soul, and make it possible to live on the spiritual plane, its ideal being the realization of Absolute Truth and the manifestation of Divinity in the actions of the daily life.

Spirituality does not depend upon the reading of Scriptures, or upon learned interpretations of Sacred Books, or upon fine theological discussions, but upon the realization of unchangeable Truth. In India a man is called truly spiritual or religious not because he has written some book, not because he possesses the gift of oratory and can preach eloquent sermons, but because he expresses divine powers through his words and deeds. A thoroughly illiterate man can attain to the highest state of spiritual perfection without going to any school or university, and without reading any Scripture, if he can conquer his animal nature by realizing his true Self and its relation to the universal Spirit; or, in other words, if he can attain to the knowledge of that Truth which dwells within him, and which is the same as the Infinite Source of existence, intelligence, and bliss. He who has mastered all the Scriptures, philosophies, and sciences, may be regarded by society as an intellectual giant; yet he cannot be equal to that unlettered man who, having realized the eternal Truth, has become one with it, who sees God everywhere, and who lives on this earth as an embodiment of Divinity.

The writer had the good fortune to be acquainted with such a divine man in India. His name was Râmakrishna. He never went to any school, neither had he read any of the Scriptures, philosophies, or scientific treatises of the world, yet he had reached perfection by realizing God through the practice of Yoga. Hundreds of men and women came to see him and were spiritually awakened and uplifted by the divine powers which this illiterate man possessed. To-day he is revered and worshipped by thousands all over India as is Jesus the Christ in Christendom. He could expound with extraordinary clearness the subtlest problems of philosophy or of science, and answer the most intricate questions of clever theologians in such a masterly way as to dispel all doubts concerning the matter in hand. How could he do this without reading books? By his wonderful insight into the true nature of things, and by that Yoga power which made him directly perceive things which cannot be revealed by the senses. His spiritual eyes were open; his sight could penetrate through the thick veil of ignorance that hangs before the vision of ordinary mortals, and which prevents them from knowing that which exists beyond the range of sense perception.

These powers begin to manifest in the soul that is awakened to the ultimate Reality of the universe. It is then that the sixth sense of direct perception of higher truths develops and frees it from dependence upon the sense powers. This sixth sense or spiritual eye is latent in each individual, but it opens in a few only among millions, and they are known as Yogis. With the vast majority it is in a rudimentary state, covered by a thick veil. When, however, through the practice of Yoga it unfolds in a man, he becomes conscious of the higher invisible realms and of everything that exists on the soul plane. Whatever he says harmonizes with the sayings and writings of all the great Seers of Truth of every age and clime. He does not study books; he has no need to do so, for he knows all that the human intellect can conceive. He can grasp the purport of a book without reading its text; he also understands how much the human mind can express through words, and he is familiar with that which is beyond thoughts and which consequently can never be expressed by words.

Before arriving at such spiritual illumination he goes through divers stages of mental and spiritual evolution, and in consequence knows all that can be experienced by a human intellect. He does not, however, care to remain confined within the limit of sense perception, and is not contented with the intellectual apprehension of relative reality, but his sole aim is to enter into the realm of the Absolute, which is the beginning and end of phenomenal objects and of relative knowledge. Thus striving for the realization of the highest, he does not fail to collect all relative knowledge pertaining to the world of phenomena that comes in his way, as he marches on toward his destination, the unfoldment of his true Self.

Our true Self is all-knowing by its nature. It is the source of infinite knowledge within us. Being bound by the limitations of time, space, and causation, we cannot express all the powers that we possess in reality. The higher we rise above these limiting conditions, the more we can manifest the divine qualities of omniscience and omnipotence. If, on the contrary, we keep our minds fixed upon phenomena and devote the whole of our energy to acquiring knowledge dependent entirely upon sense perceptions, shall we ever reach the end of phenomenal knowledge, shall we ever be able to know the real nature of the things of this universe? No; because the senses cannot lead us beyond the superficial appearance of sense objects. In order to go deeper in the realm of the invisible we invent instruments, and with their help we are able to penetrate a little further; but these instruments, again, have their limit. After using one kind of instrument, we become dissatisfied with the results and search for some other which may reveal more and more, and thus we struggle on, discovering at each step how poor and helpless are the sense powers in the path of the knowledge of the Absolute. At last we are driven to the conclusion that any instrument, no matter how fine, can never help us to realize that which is beyond the reach of sense-perception, intellect, and thought.

So, even if we could spend the whole of our time and energy in studying phenomena, we shall never arrive at any satisfactory result or be able to see things as they are in reality. The knowledge of to-day, gained by the help of certain instruments, will be the ignorance of tomorrow, if we get better instruments. The knowledge of last year is already the ignorance of the present year; the knowledge of this century will be ignorance in the light of the discoveries of a new century.

The span of one human life is, therefore, too short to even attempt to acquire a correct knowledge of all things existing on the phenomenal plane. The life-time of hundreds of thousands of generations, nay, of all humanity, seems too short, when we consider the infinite variety to be found in the universe, and the countless number of objects that will have to be known before we can reach the end of knowledge. If a man could live a million years, keeping his senses in perfect order during that long period, and could spend every moment in studying nature and in diligently endeavoring to learn every minute detail of phenomenal objects, would his search after knowledge be fulfilled at the expiration of that time? Certainly not; he would want still more time, a finer power of perception, a keener intellect, a subtler understanding; and then he might say, as did Sir Isaac Newton after a life of tireless research, "I have collected only pebbles on the shore of the ocean of knowledge." If a genius like Newton could not even reach the edge of the water of that ocean, how can we expect to cross the vast expanse from shore to shore in a few brief years? Thousands of generations have passed away, thousands will pass, yet must the knowledge regarding the phenomena of the universe remain imperfect. Veil after veil may be removed, but veil after veil will remain behind. This was understood by the Yogis and Seers of Truth in India, who said: "Innumerable are the branches of knowledge, but short is our time and many are the obstacles in the way; therefore wise men should first struggle to know that which is highest."

Here the question arises: Which is the highest knowledge? This question is as old as history; it has puzzled the minds of the philosophers, scientists, and scholars of all ages and all countries. Some have found an answer to it, others have not. The same question was voiced in ancient times by Socrates, when he went to the Delphic oracle and asked: "Of all knowledge which is the highest?" To which came the answer, "Know thyself."