8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

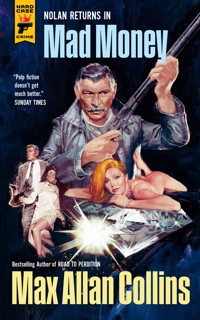

Nolan must rob every store in a mall in one night – or his girlfriend dies. Two Nolan novels from Grandmaster Max Allan Collins, collected in one volume for the first time. Nolan and Jon have put their lives of crime behind them – but when a cruel adversary from their past resurfaces, they're forced back into the heist game with a brutal ultimatum: pull off an insanely ambitious overnight robbery or Nolan's kidnapped lover won't live to see the morning. Appearing in bookstores for the first time in 35 years, this is Nolan's biggest and deadliest job – and Mad Money also features, for the first time ever in the same volume, the bonus full-length novel Mourn the Living, offering a look back at Nolan's early years as a professional thief.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Introduction

Book One Spree

Part One

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Part Two

9

10

11

12

13

14

Part Three

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Book Two Mourn the Living

Prologue

One

1

2

3

4

5

6

Two

1

2

3

4

5

6

Three

1

2

3

4

5

Four

1

2

3

4

5

6

Acclaim For the Work ofMAX ALLAN COLLINS!

“Crime fiction aficionados are in for a treat…a neo-pulp noir classic.”

—Chicago Tribune

“No one can twist you through a maze with as much intensity and suspense as Max Allan Collins.”

—Clive Cussler

“Collins never misses a beat…All the stand-up pleasures of dime-store pulp with a beguiling level of complexity.”

—Booklist

“Collins has an outwardly artless style that conceals a great deal of art.”

—New York Times Book Review

“Max Allan Collins is the closest thing we have to a 21st-century Mickey Spillane and…will please any fan of old-school, hardboiled crime fiction.”

—This Week

“A suspenseful, wild night’s ride [from] one of the finest writers of crime fiction that the U.S. has produced.”

—Book Reporter

“This book is about as perfect a page turner as you’ll find.”

—Library Journal

“Bristling with suspense and sexuality, this book is a welcome addition to the Hard Case Crime library.”

—Publishers Weekly

“A total delight…fast, surprising, and well-told.”

—Deadly Pleasures

“Strong and compelling reading.”

—Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine

“Max Allan Collins [is] like no other writer.”

—Andrew Vachss

“Collins breaks out a really good one, knocking over the hard-boiled competition (Parker and Leonard for sure, maybe even Puzo) with a one-two punch: a feisty storyline told bittersweet and wry…nice and taut…the book is unputdownable. Never done better.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Rippling with brutal violence and surprising sexuality…I savored every turn.”

—Bookgasm

“Masterful.”

—Jeffery Deaver

“Collins has a gift for creating low-life believable characters …a sharply focused action story that keeps the reader guessing till the slam-bang ending. A consummate thriller from one of the new masters of the genre.”

—Atlanta Journal Constitution

“For fans of the hardboiled crime novel…this is powerful and highly enjoyable reading, fast moving and very, very tough.”

—Cleveland Plain Dealer

“Nobody does it better than Max Allan Collins.”

—John Lutz

“Fuck,” he said.

Jon had been kneeling, looking at the discarded sacks. Now he joined Nolan.

“What?”

“I think she was dragged through here.” He pointed to the brush; a sort of path had been made, if you looked close: bushes were bent back, branches broken, snowy earth disturbed.

Nolan followed the path, pushing roughly, impatiently, through the foliage, twigs and branches snapping like little gunshots. Jon followed.

At the bottom of the incline was the curve of the road that went up into Nolan’s exclusive little housing development.

“Oil,” Nolan said, pointing to a black puddle glistening on the icy pavement. “A car was parked here. She should have noticed it when she drove by. They were waiting for her.”

“Waiting? Who? What are you talking about?”

Nolan bent and poked around in the snow at the edge of the curb. He found what seemed to be a frozen wad of white tissue or cloth; he picked it up, sniffed it.

“Jesus,” he said.

Jon said, “Will you please quit saying ‘fuck’ and ‘Jesus’ and tell me what the hell is going on?”

He held the thing under Jon’s nose. “Sniff,” he ordered.

“Jesus fucking Christ,” Jon said. “Chloroform.”

“They snatched her,” Nolan said.

“Who snatched her?”

“If I knew that,” Nolan said, “I’d know who tokill…”

HARD CASE CRIME BOOKSBY MAX ALLAN COLLINS:

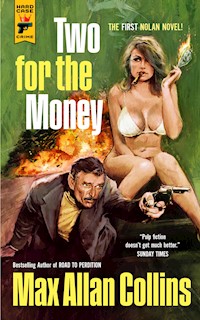

TWO FOR THE MONEY

DOUBLE DOWN

TOUGH TENDER

MAD MONEY

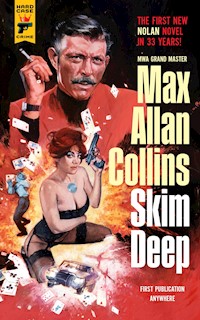

SKIM DEEP

QUARRY

QUARRY’S LIST

QUARRY’S DEAL

QUARRY’S CUT

QUARRY’S VOTE

THE LAST QUARRY

THE FIRST QUARRY

QUARRY IN THE MIDDLE

QUARRY’S EX

THE WRONG QUARRY

QUARRY’S CHOICE

QUARRY IN THE BLACK

QUARRY’S CLIMAX

QUARRY’S WAR (graphic novel)

KILLING QUARRY

QUARRY’S BLOOD

DEADLY BELOVED

SEDUCTION OF THE INNOCENT

DEAD STREET (with Mickey Spillane)

THE CONSUMMATA (with Mickey Spillane)

MIKE HAMMER: THE NIGHT I DIED

(graphic novel with Mickey Spillane)

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

A HARD CASE CRIME BOOK

(HCC-158)

First Hard Case Crime edition: April 2023

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street

London SE1 0UP

in collaboration with Winterfall LLC

Copyright © 1987, 1999 by Max Allan Collins; originallypublished as Spree and Mourn the Living

Cover painting copyright © 2023 by Mark Eastbrook

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, except where permitted by law.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Print edition ISBN 978-1-78909-146-5

E-book ISBN 978-1-78909-147-2

Design direction by Max Phillips

www.maxphillips.net

Typeset by Swordsmith Productions

The name “Hard Case Crime” and the Hard Case Crime logo are trademarks of Winterfall LLC. Hard Case Crime books are selected and edited by Charles Ardai.

Visit us on the web at www.HardCaseCrime.com

Introduction

The book you are holding, Mad Money, is the final volume in Hard Case Crime’s project to publish all of my Nolan novels. They brought out my first new Nolan novel in more than 30 years, Skim Deep, at the end of 2020, and then began reissuing the earlier titles, two to a volume, the following year. Handsome new editions of Two For the Money (collecting Bait Money and Blood Money) and Double Down (collecting Fly Paper and Hush Money) came out in 2021, and Tough Tender (collecting Hard Cash and Scratch Fever) followed in 2022. That brings us to Mad Money, which collects Spree and Mourn the Living.

* * *

Spree is the longest—and for the three decades until Skim Deep came out was the last—of my Nolan novels. Many readers consider it the best of the series, and I wouldn’t disagree.

The idea was to do a book on a larger scale than the 60,000-word fast-and-lean paperbacks of the previous entries. I’d written the first several Nathan Heller novels at this point, and those were fairly massive books—not long after Spree, I would write the Heller novel Stolen Away, which would be the longest first-person private eye novel ever written.

In addition, Donald E. Westlake, writing as Richard Stark, had written Butcher’s Moon (1974), a longer-form novel about his thief Parker than he’d ever before attempted. It turned out to be the final novel in the series, at least for a while, but its larger landscape was inspiring. After all, the Parker novels had been one of the two major influences on Nolan (the other being the Sand novels by Ennis Willie).

The Heller novels, added to my high-profile scripting of the Dick Tracy comic strip, had suddenly given me some leverage in the mystery writing field. This proved to be a passing fancy, but I took full advantage, and thanks to Nate Heller, I was able to return to two characters of my early career, characters whose development had been stunted by, frankly, having their series cancelled. That led to my writing Primary Target (retitled Quarry’s Vote in its current Hard Case Crime incarnation) and bringing my hitman Quarry back to nasty life. And it led to my resurrecting Nolan and Jon for one more caper in Spree.

There was talk at the time of relaunching Nolan as a series. The editor at Tor had made an offer on the early books and we signed a new contract. Tor had been doing the mass-market paperbacks of the Heller novels, so it was all in the family. Then Tor got outbid for the next Heller reprint by Bantam Books, and things got contract-cancelling chilly. No more Nolan novels, at least not at Tor.

All of that talk, however, had followed my submission of the novel. When I wrote Spree, I did so with the full expectation that it would indeed be the final Nolan. Because of this, I wanted to leave him in a place where readers might be able to imagine how the rest of his life might play out. And also, I wanted to give him one last score, one really major caper, to cap off his career.

Most of the Nolan novels are at least in part caper novels. They are not, however, what I would call classic caper yarns in the tradition of The Killing, Rififi, or Ocean’s Eleven, where the caper itself is a high-concept outlandish affair. Nolan’s capers were down-and-dirty—robbing a small-town bank, looting a hillbilly hideout. I wanted him to go out in style.

In the mid-’80s, shopping malls were a very big, successful deal. And the notion of heisting an entire shopping mall was a most appealing one for Nolan’s final caper. I went out to my local, then-flourishing mall in Muscatine, Iowa, and was surprised by how easily I got the security guys to show me around and explain all their systems and tricks. I remember coming home and saying to my wife Barb, “Maybe I should scrap the novel and just heist the fucking place.”

Well, what the hell—I wrote the novel. I think it came out rather well, and this is probably the best rendition of the Comfort family yet. I can’t tell you the pleasure it gave me writing the phrase, “Cole Comfort’s farm.”

The novel was optioned for the movies a number of times, and I wrote a screenplay, but it hasn’t been produced yet. We’ve tried to do it ourselves here in Iowa, but it never quite happened. Again, easier to just rob the damn mall. A new Nolan movie deal, recently signed, may rectify that.

* * *

Mourn the Living was written around 1967 or ’68, and is—in a sense—the first book in the Nolan series. (Though not the first Nolan novel to be published: that was Bait Money in 1973.)

Written during my undergrad years, Mourn the Living was set aside when an editor suggested that he would like to see either certain rewrites (with which I did not agree) or the author’s next book. I followed the latter course, figuring that Mourn would be published later on; but the subsequent series initiated by Bait Money differed from this first novel—among other things, Nolan aged ten years and acquired a youthful protégé, Jon. Also, times had changed so rapidly that the novel’s hippie-era time frame, so topical when I’d written it a few years before, seemed hopelessly dated.

It may sound unlikely, but I had forgotten about the book—at least in terms of it being a commercial property—until Wayne Dundee interviewed me for his fine small-press magazine Hardboiled. In the course of the interview, I mentioned the existence of Mourn the Living to Nolan fan Wayne, who expressed an interest in serializing it in Hardboiled.

So, twenty years after the fact, I found myself doing the necessary line-editing on the first Nolan novel. Too much time had elapsed for me to undertake any major rewriting.

While the novel was recognizably mine, I realized I was a different writer, several decades down the road; and, like any good editor, I attempted to respect the wishes and intent of the young writer who wrote it.

I hope readers will enjoy meeting the younger Nolan, sans Jon, in his first recorded adventure. As for the time period of the book being dated, I am pleased that enough years have gone by for me to present it, unashamedly, as a period piece.

My thanks to Wayne Dundee, for nudging me and giving Mourn an audience at last; to my late pal Ed Gorman, who brought out the first edition, in hardcover for Five Star in 1999; and to Barb, who patiently transferred the moldy, water-damaged manuscript onto computer disk for my editing.

And to Hard Case Crime, for including it in their collection of Nolan novels, and to you, for including it in yours.

MAX ALLAN COLLINS

BOOK ONE

Spree

To Bob Randisi—for wanting this book to happen.

The author wishes to thank Captain Tom Brendel, Chuck Bunn, Mike Lange and Ric Steed for research assistance; and editor Michael Seidman for a suggestion that proved crucial to this narrative. Thanks also to Ed Gorman and Barb Collins for convincing me to pay attention to Michael Seidman’s suggestion.

The author also wishes to acknowledge certain nonfiction source material: Crime as Work (1973), by Peter Letkemann; Crime Pays (1975), by Thomas Plate; and Game of Thieves (1981), by Robert R. Rosberg.

Part One

1

Angie McFee was wary of the Comforts, certainly, but dying violently never crossed her mind. She’d dated Lyle, after all. Well, “dated” wasn’t the word, really. She’d slept with him a few times. Sex with Lyle was energetic and fun, like your average aerobics workout. Unfortunately, conversation with Lyle was equally aerobic.

Before she drove out to the Comforts’ on this cool October evening, she got her little silver Mazda gassed up and washed. The car wasn’t quite dry, and beads of water glistened on the hood in the moonlight as she pulled off the main drag onto an asphalt road, perhaps twenty miles outside Jefferson City, Missouri. She was a petite pretty brunette of twenty-seven years, watching the moon on the hood of her car, a car the Comforts had helped buy.

It had been a shock when Lyle first suggested she meet his “pa.” Christ, it had been a shock to hear anybody in this day and age refer to their father as “Pa,” particularly without a trace of irony. It had similarly been a shock to see Lyle’s brow furrowing in something akin to thought, that thought manifesting itself in this suggestion that she meet his “pa.”

And Pa had been a shock, too. A tall, leathery farmer in coveralls and a plaid shirt with a shock (another shock!) of white hair and pale blue eyes with laugh crinkles. He had a pretty smile, Pa did, the only resemblance between him and Lyle, other than their basic lanky frame. Brown-eyed Lyle, whom she’d met in a trendy little singles bar, looked like a fashion page out of Playboy, he wore a creamy Miami Vice silk sport coat over a grayish-blue T-shirt, gray jeans, Italian shoes with no socks, a tanning spa tan, and a twenty-five-dollar haircut, when Jefferson City remained a six-dollar-haircut town. It was all so right for the fashion moment that it was a little wrong, but he had a great smile and curly brown hair and a fantastic bod and no sores on his lip. And so to bed.

Only Lyle also had a farmer drawl and a remedial reading vocabulary and a certain vacancy behind his eyes, all of which took a while to catch on to, because he was the strong silent type, the sort of brooder you assume is hiding deep thoughts behind all those pregnant pauses, when in fact those pregnant pauses prove never to give birth to anything at all, and within that pretty cranium there was, Angie had no doubt, a low and constant hum.

She had tried, on their third night together—each previous night being a month or so apart, no steady thing developing between them, just her own occasional need for some really terrific sex in the midst of her thus far fruitless search to find a better husband than the first one—to make some human connection with Lyle. She’d told him about her father’s store.

“It’s really pitiful,” she said, smoking nervously, sitting up in bed, pillow at her back, sheet pulled up but barely covering her small, pert breasts. At least she liked to think of them as pert. “Dad had this great little place, little hole-in-the-wall, where he sold nothing but meat.”

“Meat,” Lyle said, nodding. Lyle didn’t smoke.

“He’s a terrific butcher, Dad is, but a lousy businessman. When he had that hole-in-the-wall, strictly a butcher shop, with choice cuts and all, he was doing fine. Mom was keeping the books. It was great. Then he got ambitious.”

“Meat,” Lyle said.

“He thought he could do better in a bigger store—you know, a small supermarket. He thought people would come in for the great meat and buy their other food as well, save a trip, even if our prices were a little more expensive than the big discount supermarkets. Going in he knew that—knew he couldn’t compete with the prices that the big boys were able to give, because of, you know, volume.”

“Volume?” Lyle said. He narrowed his eyes, apparently wondering what noise levels had to do with the grocery business.

“Anyway, Dad’s dying with that white elephant…”

Lyle touched her arm. “I’m sorry,” he said. It was clear he had taken the word “dying” literally, and that “white elephant” was some rare disease.

“No, I just mean he’s losing his shirt,” she said, hoping he wouldn’t take that literally, too. “Our savings are gone, Mom’s too sick to work, he’s mortgaged up the wazoo. And there I am, with my business degree, stuck in the middle of a family business that can barely afford to pay me half of what I could get elsewhere.” She sighed. “But, what the hell. You got to be loyal to your family, right?”

“Right,” Lyle said, nodding again.

“So I’m keeping the books. Working in the store—sometimes behind one of the registers, which is demeaning, let me tell you. I’m glad my little boy can’t see me.”

“You have a boy?”

“Yeah, he lives with my ex. Steve’s remarried and I’m a lousy mother. I don’t think I ever want another. I mean, I love my son, but kids do get in the way.”

“Kids,” Lyle said, smiling, nodding.

“How old are you, Lyle?”

“Twenty-three.”

“Where do you work?”

“Like you. Family business.”

“Yeah, I know—you’ve said that a couple of times. But what do you do exactly?”

And that was when Lyle’s brow had furrowed suddenly, shockingly, in apparent thought.

“You keep the books?” he said.

“Yes…”

“At a grocery store?”

“Yeah, that’s right. So what?”

“You should talk to Pa.”

Pa, as it turned out, was Coleman Comfort, but, as he’d said, pale blue eyes twinkling like a slightly demented Walter Brennan, “My kith and kin all call me Cole.”

Cole Comfort’s farm, where all of their meetings had been held over the past year and a half, was off a back gravel road, on a cinder path. The two-story farmhouse seemed ramshackle somehow, despite being freshly aluminum-sided. Maybe it was the weedily overgrown yard, in which the remnants of various vehicles rusted in the process of becoming one with the universe, or the dense looming woods behind the house, where owls’ eyes and nameless critter howls seemed to invite you in but not out. Or maybe the sagging barn and decaying silo, which created suspicion as to what the house itself was like under its aluminum face-lift. Whatever the case, the Comfort place was hardly comforting and no place Angie wanted to visit.

And yet she had, once a month, for many months.

That first time, even though she had long since full well realized how thick Lyle was, the sight of the farm (and there was farmland adjacent, it just wasn’t worked by the Comforts) had made her suck in a quick breath of disbelief. “There’s money in it,” Lyle had said, “big money.” But how could there be big money here, in this Dogpatch dump? This looked like food stamp territory.

“Food stamps,” Cole Comfort had said, pouring her some Old Grand-Dad, straight up, in a fast-food restaurant giveaway glass with the Road Runner on it. They sat in the living room, where reigned a giant-screen TV on which, at the moment, Billy Joel’s face was the size of a card table. The pores in his nose were like poker chips.

Lyle was watching MTV. Cole, it seemed, hated MTV, so Lyle was listening through headphones. Giant images of singers silently shouting, dancers moving to invisible beats, were an oppressive flickering presence. Other images fought MTV for attention: six, count them, six black velvet paintings of John Wayne, paintings of various sizes but all in rough rustic frames with Wayne in western regalia, beat out the mere three jumpsuited Elvis Presleys, all of them riding walls paneled in a dark brown photographic wood grain. Against one wall, with snakes of cable crawling out of it toward the big-screen TV, was an open cabinet on wheels, in which stacks of stereo and video equipment perched, red lights dancing and sound meter needles wiggling. The furniture, all of it expensive, varied in style—from Early American to modern—but the chairs and several couches were consistent in one thing: they were covered with clear vinyl. The carpet was a green shag, like grass from outer space.

She drank the glass of Old Grand-Dad like it was soda pop and Cole grinned his pretty white grin and poured her some more.

“F-food stamps?” she managed to ask.

“Food stamps. You work in a grocery store. A little mom-and-pop affair, like in the good old days. None of this corporate horse-shit.”

“Actually McFee’s is a fairly big store,” she said. “But, yes, it’s not affiliated with any major chain. That’s the problem. They can undersell us.”

“Volume,” Cole nodded. “I stopped in the place—your daddy has a right fine meat counter.”

She couldn’t quite tell if the phrase “right fine” was an affectation or if this guy really was the hick of all hicks. Despite the tacky decor around him, Cole Comfort did not seem stupid, or even naive. Maybe bad taste and stupidity didn’t necessarily go hand in hand.

“The meat is what brings in what customers we do have,” she told him. “Daddy should never have expanded.”

Cole nodded, sagely this time; lines of experience pulled at the corners of his mouth. “It’s the bane of American business. Expansion. Nobody’s satisfied with a small success. They gotta expand till they go bust.”

Bane of American business? Where was this guy coming from?

“We’re in a position to help you, little lady,” Cole said.

Little lady yet.

“How?”

“We deal in food stamps, my family does. Lyle and Cindy Lou and me.”

She had not yet met Cindy Lou, but already an image was forming somewhere between Daisy Mae and Lolita.

“What do you mean, exactly? Your family deals in food stamps?”

“The black market, girl. Wise up. Black-market food stamps. We stay strict away from counterfeit.” He waved his hands like an umpire saying, OUT! “The real thing or nothin’ at all.”

“Well…uh, where do you get them?”

“How we get them ain’t your concern.”

“I don’t exactly understand what is my concern in all this…” Perhaps she shouldn’t have gulped that Old Grand-Dad.

“You’re the perfect conduit, the very conduit we been lookin’ for.”

Against her better judgment, she drank again from the Road Runner glass. Just a sip this time. To arm her against a man who said both “ain’t” and “conduit.”

“You can buy them from us at a thirty percent discount,” he said. “Seventy cents on the dollar.”

Now she got it. “And when I send them in…”

“The government gives you a dollar. That’s thirty cents you clear, each. And you don’t pay us till you get yours.”

She knew that wasn’t as small potatoes as it at first sounded; even with their limited business, their higher prices, McFee’s had several hundred dollars a month come in, in food stamps. Other stores their size—stores with chain-style discount prices—would do a land-office business in food stamps; at least ten times what her father’s store did.

Cole was patting her arm. “You could help your pa. He wouldn’t even have to know. You could feather your own nest, too. The government’ll never suspect a thing. We’ll help you figger what you can get away with, a store your size.”

“I wouldn’t be your only…conduit, then?”

“No,” Comfort said, his smile cracking his leathery face, “we got one or two others. But a good conduit is hard to find.”

Sew that on a sampler.

“Where do you get the stamps, anyway?”

“Nobody suffers,” Cole said. “They can get ’em replaced, if you’re worried about poor people.”

“I just want to know how it works. I know you said it wasn’t my concern, but really it is. If I’m going to be involved in something… criminal…I want to know the extent of it.”

Cole shrugged. Then his face darkened. “I hate that nigger shit!”

He was glaring past her. She glanced in that direction, at the big-screen TV, where Tina Turner was prancing, singing, in pantomime. Cole reached for a TV Guide next to him on the couch and hurled it at Lyle; the corner of it hit Lyle in the head. The son winced but did not even glance back, and certainly didn’t change the channel. He was apparently used to this form of criticism on his father’s part.

“Anyway,” Cole said, his distaste lingering in his sour expression, “we know when the stamps go out—third of the month—and that on the fifth they’re in mailboxes. Lyle and Cindy Lou just go out and about like good little mailmen, rain nor hail nor sleet, only in reverse. Taking letters out of mailboxes, not putting in.”

“It’s that easy?” she said. Repressing, and that petty?

“Yup,” he said. “It ain’t so small-time, either,” he added, as if reading her thoughts. “There can be as much as two hundred bucks’ worth in one envelope. Also, some people sell ’em to us direct. We pay a quarter on the dollar.”

“People sell their own food stamps?”

“People got things they want to buy and not eat. Sure. And we got some bars that we do business with.”

“Bars? You can’t buy liquor and cigarettes with food stamps…”

“Of course not—not ’bove board.”

“Oh,” she said. It was easy enough for Angie to figure how that could work: a bartender letting a customer use a dollar food stamp for thirty cents or so worth of booze or smokes.

“It’s a safe way to make a little extra bread, honey,” Cole said, in his fatherly way. “You won’t get caught. You almost can’t get caught. What are you doing, except moving some paper around? It ain’t even embezzling, really.”

“It is criminal,” she said.

“Much in life is,” Cole granted.

She said she wanted to think about it, and, after a particularly slow week in her father’s store, she called Cole Comfort and said yes. She never dated Lyle again. Once a month she drove to the farmhouse and got a supply of food stamps, bringing them cash in return. The Comforts always wanted cash.

And her dad, her sweet dad, tough ex-marine that he was, was so blessedly naive. He really thought business was up.

It crushed her to have to pull the rug out.

But it was time. She’d had a call from the Department of Social Services; an investigation into food stamp abuse was underway. An appointment to “interview” her had been set up. She didn’t know what this meant exactly, but she did know it was time to get out.

She’d socked a few thousand away, and bought a few toys outright (the Mazda, for one) and got her father on his feet, even if it was only temporarily. She didn’t know where she was going, but she did know she’d been in Jefferson City long enough. With her nest egg and her college degree and her looks, she could go anywhere, if she could just weather the Department of Social Services storm.

For right now, however, she was at the Comforts’, for one last time.

She was greeted at the door by Cindy Lou, a cute curvy strawberry-blond freckle-faced sixteen-year-old in a calico halter top and short jeans and bare feet with red-painted toenails. Somewhere between Daisy Mae and Lolita.

“Daddy’s upstairs figuring the books,” Cindy Lou said, ushering her into where John Wayne and Elvis, as always, ruled. “He’ll be down in a jif.”

And he was, in his usual Hee Haw apparel and his almost seductive smile. He said to Cindy Lou, “Take the pickup and get ’er gassed.”

She clasped her hands together in front of breasts that Angie would have died for. “Can I, Daddy?”

He reached in his pocket and withdrew a twenty and, grinning shit-eatingly, said, “What’s it look like?”

She snatched it out of his hands, and he patted her round little butt in a less than paternal way as she departed. Angie wondered for a moment whether Cindy Lou was old enough to have a license, before dismissing it as a foolish question.

He bade her sit on the couch again, which she did, where he poured her Old Grand-Dad and she carefully, tactfully, explained her position. Lyle was watching MTV, in headphones. Rick James was on the screen, silently screaming, but this time Cole didn’t hurl a TV Guide. Maybe he was getting more tolerant.

Or maybe he was just preoccupied.

She withdrew from her purse an envelope of cash, which he riffled through, smiling absently; he usually gave her a thick packet of food stamps at this point. He was preoccupied tonight.

“This investigation,” Cole said, tucking the money away in a deep coverall pocket, “what have you heard, exactly?”

“Nothing,” she said, shrugging expansively.

“They ain’t even talked to you yet.”

“Just on the phone. It’s only an appointment.”

“Are you worried?”

“Sure I am. But I don’t see how they can prove anything.”

“Damn,” Cole said. His smile was as rueful as it was pretty. “This has been one sweet little scam—but I’m afraid its days are numbered.”

“This investigation is that serious, you think?”

“Hard to say. I can tell you this—they started registering the mail with the food stamps in it. Anything over ninety bucks gets registered. Recipient has to sign.”

“So your kids can’t go raiding mailboxes anymore.”

“Not like they could. It’s just too damn bad.”

She shrugged. Smiled. “It was fun while it lasted.”

“Sure was,” he said, and hit her on the side of the head with the Old Grand-Dad bottle. She heard the glass break against her jaw, felt her skin tear, a flash of pain, then darkness.

She came out of it, once, for a moment, hearing: “A girl, Pa? I don’t want to kill no girl. I was with her before.”

That was when, for the first time, dying violently occurred to her.

2

In Nolan’s life, right now, comfort was very important.

He’d lived hard, for fifty-some years, and it seemed to him about time to take it easy. This was the payoff, wasn’t it? What he’d worked for, for so very long: the good life.

Not that he wasn’t still working. He liked to work. His restaurant-cum-nightclub, Nolan’s, nestled in a nicely prosperous shopping mall, was doing a tidy business and he put in, oh, probably a fifty-hour week. He did all the buying himself, and kept his own books, did all the hiring and firing as well as playing host most evenings. No, he didn’t greet his patrons at the door—he had a hostess for that—but he did circulate easily around the dining room, asking people if they were enjoying their meals; and in the bar he’d move from stool to stool, table to table, chatting with the regulars.

Right now he was at home, though, in the open-beamed living room of his big ranch-style house, home on a Friday night (a rarity), a gaunt-faced, rangy man stretched out in a recliner, stroking his mustache idly, watching the reason for staying home on a Friday: a boxing match on HBO, a black guy and a Puerto Rican bashing each other’s brains out on a twenty-seven-inch Japanese TV screen. Nolan’s idea of world unity.

The room around him was cream-color walls and modern furnishings and soft browns. What he wore matched the room, though he hadn’t intended or even noticed it: a cream-color pullover sweater and brown corduroy trousers and brown socks and no shoes, vein-roped hands folded over a slight paunch.

The paunch bothered him, but not much. He’d been a lean man so long that in his mind he still was. Eating the food at his own restaurant had done it to him, and he’d taken up golf to halfheartedly work the budding Buddha belly off. Toward that end, he rarely rode in the cart, walking, trying to make it feel like a real sport.

He was enough of a natural athlete to break one hundred the first month he played, which frustrated the rest of his regular foursome, who, like him, were in the Chamber of Commerce, with stores in or near the Brady Eighty mall. Harris owned a nearby Dunkin’ Donuts outlet, a twenty-four-hour operation, and frequently handed Nolan a free dozen, which didn’t help his weight, either. Levine owned the Toys ‘R’ Us franchise in Brady Eighty. DeReuss, the wealthiest and quietest, was a Dutchman who owned a jewelry store in the mall. After eighteen holes, the foursome would go to the country club bar and drink and talk sports and women. Nolan liked the three men. He felt, at long last, as if he’d joined the real world. The legit world.

He sometimes wondered, in rare reflective moments, for instance between rounds tonight, what his friend DeReuss who owned the jewelry store would say if he knew Nolan had, in his time, heisted many similar such stores, albeit never in a mall. He didn’t know where his three golfing chums had got their financing, but Nolan had done it the good old-fashioned American way: he’d gone out and taken it.

For nearly twenty years, prior to this current respectability, Nolan had been a professional thief.

Jewelry stores—along with banks, armored cars and mail trucks—were his pickings, though not easy. He prided himself on the care he took; he was no cheap stick-up artist, but a pro—big jobs, one or two a year, painstakingly planned to the finest detail, smoothly carried out by players carefully cast by Nolan himself. Nobody got hurt, especially civilians; nobody went to jail, especially Nolan. He ran the show. He always had.

Well, not always. He’d started with the Family, the Chicago Family that is, but not in a criminal capacity. And certainly not in the heist game; in his experience, Family guys themselves rarely got into honest stealing, though they frequently bankrolled it. Unions and vice were where the Family was comfortable doing their stealing, and Nolan wanted none of either.

He hadn’t meant to go to work for the Family at all; he didn’t know that the Rush Street club where he was hired as a bouncer was Outfit-owned until he saw the manager paying off one of Tony Accardo’s cousins.

That same manager was stupid enough to short the Family on its piece of the proverbial action, and left in a nervous hurry one night. Nolan never knew whether the little man had made it to safety or the bottom of Lake Michigan, and he didn’t much care which. All he knew was it opened up a slot for him—soon he was managing the club himself, and still doing his own bouncing, making a name with the made guys, who eventually tried to get Nolan to join the Sicilian Elks himself, only he passed. They resented that, and tried to pressure Nolan into bumping off a guy he knew pretty well, and Nolan balked, and somebody else killed the guy, which somehow led to Nolan shooting (through the head) the brother of a Family underboss. Messy.

That had sent him scurrying into the underground world of armed robbery, which—with the exception of the aforementioned occasional bankrolling, a money source Nolan never sought—rarely touched Family circles. In that left-handed world he’d made his mark, and a lot of money. And, eventually, time cooled his Family problems—he had outlived the bastards, basically, and was now on more or less friendly terms with the current regime. He’d even operated a couple of clubs for them.

But he wanted to have something of his own. He didn’t like having Family ties; it wasn’t his idea of going straight, and straight was where he had always hoped to go, deep in the crooked years.

So here, finally, in the Quad Cities, a cluster of cities and towns on the Iowa/Illinois border, which is to say the Mississippi River, he had settled down and bought his restaurant and gone there: straight.

Funny. It all seemed so long ago—half a dozen guys standing around looking at maps and blueprints and photographs spread out on a motel-room bed or somebody’s kitchen table. Cigarette and cigar smoke forming a cloud. Beer and questions and arguing and bragging. Some really great guys—like Wagner and Breen and Planner. And once in a while a real asshole—like any one of that crazy Comfort clan. Well, Sam Comfort and his boys were all dead now, and their vendetta against him was just as dead. Nothing to worry about.

The black boxer won, and Nolan was yawning through some situation comedy, of the cable variety—stale pointless jokes and naked female breasts, not pointless—when the phone rang. He used the remote control to turn down the TV sound and walked to the kitchen where the phone was on the wall.

“Nolan,” he said.

“Hi. Is the fight over, or am I interrupting?”

It was Sherry. The hostess at his restaurant. She lived with him, a beautiful twenty-two-year-old California blonde from Ohio, young enough to be his daughter. But she wasn’t.

“The fight’s over. You’re not interrupting anything. How’s business?”

“I love you, too. Business is fine. You wouldn’t want to come down and work a few hours, would you?”

“Need me?”

“I always need you. But at the moment I’m thinking of the bartender.”

“Crowded,” he said, smiling.

“There’s money in your voice,” she said. “You really love the stuff, don’t you?”

“What else is there?”

“Me.”

“You’re in the top two.”

“You really know how to sweet-talk a girl. Get down here, will you? The regulars are asking for you.”

“It’s nice to be loved.”

“So I hear,” she said, hanging up, but there was no real bitterness in her voice. It was just a game they played.

She knew he loved her, or at least he assumed as much. That is, assuming he loved her. He wasn’t sure. He wasn’t sure what love was, exactly, except something in movies and on TV, and on his TV right now, sound down, were some girls soaping themselves in the shower, which wasn’t love exactly, but was close enough.

He showered, too, alone, and shaved and splashed on Old Spice, an old habit, and put on a blue suit and a dark blue tie and a pale blue shirt, all of them quite expensive. He bought them locally, at the mall, where he got a discount; and he only wore such clothes to his restaurant, enabling him to deduct them.

Nolan loved money so much, he hated to spend it. He knew it was ridiculous—he wasn’t going to live forever, and these were the years where he was supposed to be enjoying himself, and, damnit, he was. He’d bought this fucking house (he only thought of it as a “fucking house” when he remembered what it cost him) and had expensive toys, like his silver Trans Am and several Sony TVs and stereo equipment and the sunken tub with whirlpool and like that. But he knew each one of the toys had taken Sherry’s nudging to get bought.

He smiled, thinking of her, slipping into a London Fog raincoat, twenty percent discount from the Big and Tall Men’s shop at the mall. He’d met her at the Tropical, a club he ran for the Family a few summers back. She was a waitress and he’d fired her for spilling scalding hot coffee in a customer’s lap. Then she sat on his, and they wound up spending the summer together. When she wasn’t in a bikini, poolside, she was in his bed and wasn’t in a bikini.

He pulled the silver sporty machine out of the garage, closing the overhead door behind him with a push of a button, wondering if some smart crook would come through the neighborhood trying various frequencies on some homemade open-sesame doohickey till he got it right and got in. More power to him, Nolan thought, and besides, my alarm will nail the bastard.

He glided down the hill—it was a cold clear November night—and turned left, toward Moline, coasting along a stretch that alternated between parks and commercial and residential, a Quad Cities pattern. He was still thinking about Sherry. Still smiling.

What had started, that one summer, as two people using each other—a cute lazy cunt who wanted to stay on the payroll and was willing to do it by screwing the boss, lecherous dirty old man of fifty that he was—had turned into something else. Something more.

They liked each other. The sex was good, and the summer was over too soon. He had asked her to stay on, and she almost had, but her mother had a stroke and she had to go home, so they parted company, reluctantly, and he promised her she’d hear from him again. A year ago or so, when he bought Nolan’s (which had been the name of the place even before he bought it, and she often accused him of buying it so he wouldn’t have to spend money on a new sign), he had thought of her and invited her to work for him and, if she liked, stay with him. Despite her scalding-coffee-in-the-customer’s-nuts past, he made her hostess. And she’d done very well at it. She was beautiful, of course, but she had that midwestern gift of making immediate friends out of strangers. She, more than anyone or anything else at Nolan’s, was responsible for the heavy return business, the regulars who haunted the place.

He crossed the free bridge at Moline. The river was choppy tonight; the amber lights of the cities on its either shore winked on the water. Did he love her? He supposed so. He liked her, and that somehow seemed more important.

He stayed on Highway 74 and curved around onto Kimberly, a wide street whose valleys and hills were thick with commerce; he glanced at the little shopping clusters, wondering how they were doing. He knew Brady Eighty was hurting everybody else—but it might be temporary. New kid on the block always got more attention—for a while.

He turned right on Brady Street, a four-lane one-way clear to the Interstate now, and enjoyed the almost Vegas-like glow of fast-food franchises and other prospering businesses. The Quad Cities economy wasn’t good—the farm implement industry, a major component of the area’s economy, was withering away, and other local industries were suffering as well. But Brady Street glowed in neon health: pizza and tacos and hamburgers; used cars, stereos and videotape rental. People always have money for the important things.

Like drinking, he thought, with a wry private smile, turning toward his club. At this point on Brady, the businesses began to give each other some breathing room, and the food wasn’t so fast—although Flaky Jake’s, for all its yuppie pretension, was still a hamburger joint, and Chi-Chi’s peddled tacos, even if they did slop guacamole and sour cream on them. This was motel country, too: Ramada, Best Western, Holiday Inn. At the left as he passed, in a valley of its own, lay the sleeping behemoth—NorthPark—the massive, sprawling shopping mall whose parking lot was an ocean of cement that even after closing was swimming with cars—movies and restaurants kept it so. North Park was Brady Eighty’s biggest (in every sense) competitor, and conventional wisdom had said a new mall nearby couldn’t hope to compete with its scores of shops, including four major department stores.

But Brady Eighty wasn’t exactly a new mall. It was a refurbished one. The Brady Street Shopping Center, an open-air plaza with two rows of shops facing each other, had opened back in the early sixties, one of the first in the Cities. Over the years it had fallen on hard times, and was almost a ghost town when a Chicago-based group, led by a smart operator named Simmons, bought everybody out but a few willing-to-stay stalwarts and remodeled the place into an enclosed mall. The Brady Street location—Highway 61, just a whisper away from Interstate 80—made it the first shopping area you saw when you got off the Interstate; provided the easiest shopping-center access for half a dozen small towns outside of Davenport; and had a varied selection of shops, within a smaller, easier-to-deal-with area than North Park’s miles of mall. “Brady for the ’80s,” the slogan went, and Nolan wondered idly what would happen to the catchphrase now that the nineties were breathing down the decade’s neck.

Nolan pulled into the dimly lit, pleasantly crowded parking lot, admiring the glow of the green neon Nolan’s sign on the side of the mall wall, at the right of the front entry. The words “Brady Eighty” in silver-outlined-black art deco letters were along the long window over the bank of doors. And speaking of banks, First National’s outlet was opposite Nolan’s, at left, with a drive-up window. It amused Nolan to be doing business across from a bank.

He couldn’t find a parking place up close, so he pulled around back. The parking lot in back wasn’t full, even on a Friday, partly because people didn’t seem to know it existed yet, and partly because the rear double doors were locked up after the mall closed. His was the only business open after hours, and had its own after-hours entry/exit accordingly, under that glowing green “Nolan’s” neon.

As he got out of the Trans Am, the wind whipped out at him, cutting through the raincoat, whistling through the skeletal trees behind him, beyond the parking lot. He realized how, in a way, this thriving little mall was situated in a rather desolate spot. Woods and farms and highways were its neighbors; you had to drive half a mile to run into commercial and residential again. Stuck out in the boonies, they were—making a small fortune.

He used a key to get in the double doors, and his footsteps echoed pleasantly down a hallway between Petersen’s, a big department store at left, and the Twin Cinemas, which hadn’t opened yet. This new addition—taking over the area of a water-bed store and an antique boutique, the only businesses at Brady Eighty to fail since its opening two years ago—was the only space not up and running. No other mall in the Cities could say the same—even North Park had its share of shuttered stalls.

He walked down the deserted mall, its walkway area quite wide, having been a plaza back in the unenclosed, pre-mall “shopping center” days, and well-dressed manikins in store windows stared at him, threatening to come to life. One of them did, only it was just the security guard, Scott, a pasty-faced kid of twenty-five who carried a phallic billy club on his belt, and no gun. Nolan liked the kid well enough, but he kept telling the mall manager to put two guards on, and make one of them an older guy, a retired cop. Nolan, like any good thief, knew what the possibilities were. Imagine, if somebody got in here one night and just started helping themselves.

He turned the corner and walked down to the Nolan’s mall entrance, which also was kept locked after hours, to keep his customers from strolling the mall. He unlocked the door and went in; music assaulted him, some vaguely British-sounding youth mumbling about love against synthetic strings and hollow percussion. Fridays and Saturdays, after ten, a deejay came in and the little dance floor, over at the left, was crowded with approval. Nolan shrugged. Whatever sells.

He felt the same about the look of the place—barnwood and booths with lots of nostalgic bric-a-brac on the walls, tin advertising signs, framed forties movie posters, the occasional historic front page; and lots of plants, hanging and otherwise. Sherry had done it, the decorating. Better she do it here than at home.

He went behind the bar and asked Chet, an older man he’d hired away from a place downtown, how the evening was going. Chet said A-OK, but had to shout. Nolan occasionally worked behind the bar, but only in a crunch; if Chet needed him, he’d say so. Nolan found a stool and looked at his crowd. Weekends were singles-dominated—meat market time. Some Big Chill-variety married couples, but mostly singles; he had a smaller, older crowd during the week. His friends from the Chamber of Commerce and country club would come by, spend some time, some money. He liked it here during the week.

He liked it here now, too, only in a different way. He liked the way the cash register rang on weekends; it played his favorite song. So, what the hell—these marks could listen to their favorite song, too, even if it was by some adenoidal Brit twit.

Sherry came over; she was wearing a red jumpsuit with Joan Crawford shoulders and a wide patent-leather belt. The outfit was Kamali, she said; that was a brand name, apparently.

Square shoulders or not, she looked terrific. Sculpted blond hair around a heart-shaped face with big blue eyes and long, real lashes and soft, puffy lips that pouted prettily even when she smiled.

Like she was now.

“You came,” she said.

“In my pants,” he said. “It must’ve been the sight of you that did it.”

She cocked her head to one side and shook it gently, smiled the same way. “No. It was the sight of all these customers.”

Nolan shrugged, almost smiled.

“You love being a prosperous businessman, don’t you?” she said.

“It ain’t half bad,” he said.

She stood very near to him, where he sat on a barstool.

“You love playing it straight, too, don’t you? You get a kick out of playing at being honest.”

“Aren’t you supposed to be working?”

“When somebody comes in that door, I’ll be there to greet them. I’ve come a long way from the Tropical.”

“I still don’t want you pouring any coffee.”

She touched his knee. “Haven’t you noticed? I’ve gotten better with my hands as I’ve gotten older.”

“You can get a five-yard penalty for holding, you know.”

She removed her hand, and her pouty smile turned wry. “That’s you, all right, Nolan. The referee of my life.”

“Maybe so, but I’m always interested in a forward pass. Somebody.”

“Huh?”

“Just came in. Do your duty.”

She went over to the door, where a handsome well-dressed brown-haired kid in his early twenties seemed glad to see her. Then he realized she was just the hostess, and when she realized he wasn’t here to dine, she merely pointed him to the bar area and dance floor, where he slipped into the crowd, just another would-be John Travolta. Or whoever this year’s hunk was.

Nolan said, “I think he liked you.”

“Dumb as a post. You could see it in his eyes. Well, anyway, I was saying. You’re an honest man, now. Why don’t you make me an honest woman?”

“Are you proposing?”

“No, just kidding. On the square. You know, we’ve been honeymooning since I was in puberty. You might want to consider something more serious.”

She smiled a tight little, crinkle-cornered smile, that wasn’t pouty at all, and left him alone at the bar to think about this. Which he never had before. Sherry was the first woman he ever lived with, for any length of time; he’d figured that in itself was a commitment, the biggest he’d ever made to a woman, anyway.

But, hell—he was a businessman, now. A straight, prosperous businessman—who happened to be living with a girl less than half his age. How did it look? The Chamber had its share of bluenoses, after all. Maybe marriage was the appropriate thing.

Nolan asked Chet for a Scotch, a single, and smiled to himself. I am going soft, Nolan thought. Seriously considering marriage. Worrying about how things look, what people would say. What would Jon say?

Across the room, at a small table, where he sat alone, feeling the glow of the eyes of appreciative single women upon him, Lyle Comfort squinted at the man at the bar and, slowly but certainly, like fire from the efforts of a stubborn Boy Scout rubbing rocks together, a thought formed.

Lyle Comfort, who just two hours ago was burying someone he’d killed in a wooded area across the river, recognized Nolan.

Quietly, he got up and left.

3

Lyle Comfort didn’t like killing people. But he did what he was told. That was his best quality: he was a good boy. He did what his pa said.

Tonight he had killed his sixth person in three weeks; that was two killings a week, though it hadn’t worked out that way exactly.

The first was the hardest. The girl. Angie. He’d killed her when she was still unconscious, so it wasn’t cruel. He’d shot her in the heart with a revolver, the Colt Woodsman Pa gave him for his last birthday. He couldn’t bear to shoot her in the head; it might mess her face up. He had buried her in the woods, a couple miles from the house, nice and deep. Hers wasn’t the only body buried out there.

But she was the first girl he ever killed. First woman. It was a good thing he didn’t believe in God anymore, or he’d go to hell, sure. But Pa said God was something fools believed in to keep from going crazy thinking about dying. And he also said that dying was something that caught up with everybody, so exactly when somebody died was no big thing. It wasn’t like it wasn’t going to happen anyway.

That made sense to Lyle, and made it easier to do the things he sometimes had to do, for Pa. The other thing Pa said that helped was: “Business is business. Money makes the world go ’round, and a man’s family’ll starve if he don’t do what’s necessary to bring in the bucks.”

So Lyle, obedient son that he was, did what was necessary to help Pa bring in the bucks.