Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

Acclaimed "True Crime" detective Nathan Heller, whose cases have sold more than 1 million copies, returns to uncover the secrets behind Robert F. Kennedy's 1968 assassination in this brand-new novel from bestselling ROAD TO PERDITION author Max Allan Collins. A HELL OF A FINALE TO A DECADE OF ASSASSINATION It began with John F. Kennedy in 1963. Then Malcolm X in 1965. Martin Luther King in April 1968. And then, in June of the same year, President Kennedy's brother Robert fell before an assassin's bullets at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. But how many shooters were there, really? And who sent them? In this astonishing, meticulously researched novel, bestselling author Max Allan Collins – Mystery Writers of America Grand Master – takes Nathan Heller, "Private Eye to the Stars," from the scene of the crime to Hollywood's seediest haunts, from striptease joints to Washington D.C.'s corridors of power to a deadly desert showdown outside Las Vegas, all in pursuit of the truth about a conspiracy that may have put the wrong man in jail, let the real killers go free, and snuffed out the life of a man poised to become the next president of the United States.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 400

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Acclaim for the Work of Max Allan Collins!

Hard Case Crime Books by Max Allan Collins

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Author’s Note

Part One: The Path Through the Pantry

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Part Two: The Girl in the Polka-Dot Dress

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Part Three: The Go-Go Dancer with the Zebra Rug

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Part Four: Welcome to Survival Town

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

I Owe Them One

About the Author

Acclaim For the Work ofMAX ALLAN COLLINS!

“Crime fiction aficionados are in for a treat…a neo-pulp noir classic.”

—Chicago Tribune

“No one can twist you through a maze with as much intensity and suspense as Max Allan Collins.”

—Clive Cussler

“Collins never misses a beat…All the stand-up pleasures of dime-store pulp with a beguiling level of complexity.”

—Booklist

“Collins has an outwardly artless style that conceals a great deal of art.”

—New York Times Book Review

“Max Allan Collins is the closest thing we have to a 21st-century Mickey Spillane and…will please any fan of old-school, hardboiled crime fiction.”

—This Week

“A suspenseful, wild night’s ride [from] one of the finest writers of crime fiction that the U.S. has produced.”

—Book Reporter

“This book is about as perfect a page turner as you’ll find.”

—Library Journal

“Bristling with suspense and sexuality, this book is a welcome addition to the Hard Case Crime library.”

—Publishers Weekly

“A total delight…fast, surprising, and well-told.”

—Deadly Pleasures

“Strong and compelling reading.”

—Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine

“Max Allan Collins [is] like no other writer.”

—Andrew Vachss

“Collins breaks out a really good one, knocking over the hard-boiled competition (Parker and Leonard for sure, maybe even Puzo) with a one-two punch: a feisty storyline told bittersweet and wry…nice and taut…the book is unputdownable. Never done better.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Rippling with brutal violence and surprising sexuality…I savored every turn.”

—Bookgasm

“Masterful.”

—Jeffery Deaver

“Collins has a gift for creating low-life believable characters …a sharply focused action story that keeps the reader guessing till the slam-bang ending. A consummate thriller from one of the new masters of the genre.”

—Atlanta Journal Constitution

“For fans of the hardboiled crime novel…this is powerful and highly enjoyable reading, fast moving and very, very tough.”

—Cleveland Plain Dealer

“Nobody does it better than Max Allan Collins.”

—John Lutz

For a frozen moment the shooter maintained his position as if he were between rounds at a firing range, and I pushed through and practically crawled over the people scrambling to find safety in the small space and I probably damn near trampled several, but I dove at the little bastard and shoved him against one of the steel serving tables.

Breathing hard, I yelled, “Take him!”

But our captive was shooting again, orange-blue flames licking out the barrel of the .22, and bystanders were falling like clay pigeons over five or six seconds that felt like forever. Finally he was clicking on an empty chamber.

Five wounded besides Kennedy were slumped on the floor here and there, in various postures of pain and shock. Bob was spread-eagled as if nailed to a cross waiting to be raised into proper crucifixion position, precious blood pooling like spilled wine and shimmering, reflecting the popping flashbulbs…

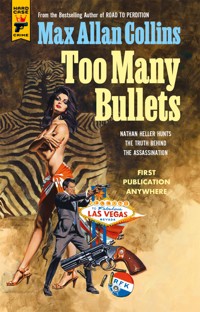

HARD CASE CRIME BOOKSBY MAX ALLAN COLLINS:

THE BIG BUNDLE

TOO MANY BULLETS

SKIM DEEP

TWO FOR THE MONEY

DOUBLE DOWN

TOUGH TENDER

MAD MONEY

QUARRY

QUARRY’S LIST

QUARRY’S DEAL

QUARRY’S CUT

QUARRY’S VOTE

THE LAST QUARRY

THE FIRST QUARRY

QUARRY IN THE MIDDLE

QUARRY’S EX

THE WRONG QUARRY

QUARRY’S CHOICE

QUARRY IN THE BLACK

QUARRY’S CLIMAX

QUARRY’S WAR (graphic novel)

KILLING QUARRY

QUARRY’S BLOOD

DEADLY BELOVED

SEDUCTION OF THE INNOCENT

MS. TREE, VOLS. 1-5 (graphic novels)

DEAD STREET (with Mickey Spillane)

THE CONSUMMATA (with Mickey Spillane)

MIKE HAMMER: THE NIGHT I DIED

(graphic novel with Mickey Spillane)

Too ManyBULLETS

byMax Allan Collins

A NATHAN HELLER NOVEL

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

A HARD CASE CRIME BOOK

(HCC-160)

First Hard Case Crime edition: October 2023

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street

London SE1 0UP

in collaboration with Winterfall LLC

Copyright © 2023 by Max Allan Collins

Cover painting copyright © 2023 by Paul Mann

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, except where permitted by law.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Print edition ISBN 978-1-78909-946-1

E-book ISBN 978-1-78909-947-8

Design direction by Max Phillips

www.signalfoundry.com

Typeset by Swordsmith Productions

The name “Hard Case Crime” and the Hard Case Crime logo are trademarks of Winterfall LLC. Hard Case Crime books are selected and edited by Charles Ardai.

Visit us on the web at www.HardCaseCrime.com

For DAVE THOMASfriend and collaborator.Today’s topic…

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Although the historical incidents in this novel are portrayed more or less accurately (as much as the passage of time and contradictory source material will allow), fact, speculation and fiction are freely mixed here; historical personages exist side by side with composite characters and wholly fictional ones—all of whom act and speak at the author’s whim.

“Success was so assured and inevitablethat his death seems to have cut intothe natural order of things.”JOHN F. KENNEDYON HIS BROTHER JOE’S WARTIME PASSING

“This could very easily happen.”GEORGE AXELROD, SCREENWRITER,THE MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE

“If they’re going to shoot, they’ll shoot.”PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE ROBERT F. KENNEDY,APRIL 1968

TOO MANY BULLETS

PART ONE

The Path Throughthe Pantry

June 1968

ONE

At the end of this narrative, certain guilty people go free. You may even feel I’m one of them. Some will pay, while others will not, enjoying the unearned happy remainders of their lives. And any reader inclined to dismiss everything ahead as a conspiracy theory might keep in mind that conspiracy—like robbery and rape, murder and treason—is a real crime on the books. History, I’m afraid, is a mystery story without a satisfying resolution.

But know this: I did get some of the bastards.

* * *

The sullen sky seemed to know something we didn’t. Fog lingered over a wind-riled sea under a gray ceiling while a mist kept spitting at us like a cobra too bored to strike. Gun-metal breakers shooting white sparks rolled in like dares or maybe warnings.

It was a lousy day at Malibu Beach, so of course Bob Kennedy was helping his ten-year-old son Michael build a sandcastle while twelve-year-old David swam against the tide—like Mr. Toad, going nowhere in particular—and nine-year-old Mary and eleven-year-old Courtney laughed and danced in the relentless surf.

U.S. presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy wore an unlikely loud pair of Hawaiian swim trunks and a nubby short-sleeve shirt as light blue as his eyes. I had on borrowed red swim trunks and my own Navy blue polo, the patriotic complement of my pale Irish complexion undone by a tan realized lazing around the pool at the Beverly Hills Hotel on better days.

I was, and for that matter still am, Nathan Heller, president and founder of the A-1 Detective Agency out of Chicago, putting time in at our Los Angeles branch. In such instances the Pink Palace (as the Beverly Hills Hotel was known) provided me with a bungalow, a perk for the A-1 handling their security. I’d come out this afternoon to this private stretch of sand at my friend Bob’s request.

None of us called him Bobby, by the way. Not even Ethel, who was in the beach house playing Scrabble with two other kids of theirs, sixteen-year-old Kathleen and fifteen-year-old Joe. Normally all of them would be frolicking in the California sun, only of course there wasn’t any. The wife and older siblings had shown enough sense to come in out of the chill wind off the ocean, away from fog drifting over the water like the smoke of a distant fire.

Bob Kennedy was forty-two and I was a year younger than Cary Grant, a fit 185 pounds with my reddish brown hair graying only at the temples. Bob was fit too, five ten and slender, wiry in that way that keeps you going. But he’d been campaigning his ass off and had admitted to me he’d damn near collapsed after doing 1,200 miles in twelve hours—Los Angeles, San Francisco, Watts, San Diego and back to L.A.

“Ethel and I slept till ten today,” he’d admitted.

I was here filling in. Ex-FBI man Bill Barry had come down with Montezuma’s Revenge after the Cesar Chavez swing, and tonight at the Ambassador Hotel I would mostly be at Ethel’s side when her husband was braving crowds. I was already wishing I hadn’t said yes and the frosty breakers rolling in and the spitting wind had nothing to do with it.

Bob had called last night.

I said, “Bill was in charge of security, right?”

That familiar nasal high-pitched voice came back with, “Uh, right. That’s right.”

“How many people does he have working for him?”

“None.”

“What does that mean, none?”

“Bill’s all the security I need.”

“Oh, that’s crazy. I can bring half a dozen guys along and—”

“No. The hotel took on extra guards. They have something like seventeen men in uniform lined up.”

“Okay. How much LAPD presence?”

“None.”

“Does that mean the same thing as the other ‘none’?”

“It does. Nate, police presence sends the wrong message. Anyway, I, ah, am not on the best of terms with Chief Reddin.”

“Jesus Christ.”

“Oh, He’ll be there, pursuant to availability.”

That caustic sense of humor often caught me off guard, and before I could muster a comeback, he said quickly, “Come out and have lunch with us around noon and we’ll talk more.”

He’d already told me he was staying at film director John Frankenheimer’s. My name would be left at the guard shack where you entered the Malibu Colony. Well, at least the director of Seven Days in May maintained some security.

The two girls in their swim caps and one-piece swimsuits were splashing each other and laughing and now and then their joyful yelps would escalate into little girlish screams.

Bob tousled Michael’s hair and left him in charge of castle building, then joined me on our towel-spread patch of beach.

“That’s the one consolation if I lose,” he said.

That famous boyish face had deep lines now and the blond-tinged brown hair had gray highlights.

“What consolation is that?”

“Spending more time with my kids.”

“You really think you might lose?”

He shrugged a little. “Touch and go. And if I do win, there’ll be a world of bitterness to overcome.”

“McCarthy you mean.”

Bob nodded. “Already a lot of resentment from Gene and, uh, his young supporters.”

“Tell me about it,” I said. “My son is campaigning for him.”

“Good for him. How old is Sam now?”

“Twenty-two. Another year of college and he’ll be draft fodder.”

Bob’s mouth tightened. “Not if I can help it.”

Sam, my only child, was a senior taking Business Administration at USC. He still lived at home in Bel Air with my ex-wife and her film director husband, who was no John Frankenheimer but did all right. When I was in town, Sam would bunk in with me at my Pink Palace bungalow. We’d go to movies, concerts, sporting events; he’d let his old man buy him good meals. We got along well.

“Fuck you, Dad!” he’d said this morning.

I had just told him about my call from Bob. That I’d be working security for the RFK campaign tonight.

Sam was a good-looking kid, by which I mean he resembled me, excluding his shoulder-length hair and mustache (and MCCARTHY FOR PRESIDENT t-shirt and bell-bottom jeans). I suppose twenty-two wasn’t really a kid, but when you’re a year younger than Cary Grant, it seems like it. We rarely argued and hadn’t talked politics beyond both being against the war in Vietnam, neither of us wanting him to go off and die in a rice paddy.

I hadn’t discouraged his work for the McCarthy campaign. And when Bob announced his candidacy, late in the game, I didn’t reveal how I felt about the two Democratic candidates… that I considered RFK way more electable than that aloof cold fish Eugene McCarthy. Richard Nixon, who had been batting away all comers in the Republican primaries, was a tough, seasoned candidate who’d be hard to beat, though his lack of charisma would be a boon to a Kennedy running against him.

We were in the living room of my pink-stucco bungalow, a modest little number with rounded beige and brown furniture, vaulted ceiling, fireplace, and sliding glass doors onto a patio. I was on the couch and my son stood ranting and raving before me.

“Haven’t we had enough of these goddamn Kennedys? Eugene McCarthy puts his career on the line, takes on a sitting president and shows America that evil S.O.B. LBJ is vulnerable! Your Bobby sees what Senator McCarthy has pulled off and decides to just, just…horn right in!”

“I’m not going to argue with you, son.”

“Of course not, because you know damn well that Bobby Kennedy doesn’t have a single solitary idea, much less a plan, on how to get us out of the goddamn Vietnam quagmire!”

I sighed. “McCarthy can’t beat Nixon, Sam. Hell, he can’t beat Hubert Humphrey for the nomination. But Bob could beat ’em both.”

Sam was pacing now. “How long ago was it your ‘Bob’ was saying he’d back Johnson, despite all the anti-Vietnam talk? He’s a phony, Dad. A goddamn fucking phony. Just another politician. Another Kennedy.”

The last thing I wanted in the world was for my son to go to Vietnam. But sometimes I thought the military wouldn’t be such a bad experience for him.

Of course, he’d have to live through it.

“This isn’t worth us working ourselves into a lather,” I said. “Bob is an old friend, and he’s in a jam with his security guy dropping out. This is just a job, a favor really, for a friend.”

His chin crinkled; he looked like a baby with a mustache. “Are you going to vote for McCarthy if he gets the nomination?”

“Are you going to vote for Humphrey if he gets it?”

His eyebrows rose and hid in his hair. “Fuck no! Why even vote in that case?”

“Oh, I don’t know. To save your spoiled ass?”

He threw his hands up in sullen surrender. “I’ll get my things. You’re heading back to Chicago tomorrow, right? I’m going back home now. Good fucking bye.”

I could have told him what I believed would happen, which Bob Kennedy surely already knew. Even if Bob won delegate-rich California, that left New York, where many resented the way he’d put his presidential bid above his senatorial duties. Bob did not have a lock on the convention by any means, but even if the Kennedy magic and emotion didn’t sway the delegates to him, he could almost certainly squeeze the vice presidency out of Humphrey and move that old liberal away from Johnson’s war policy and onto the RFK anti-war view.

The presidency would be Bob’s, though maybe not till 1976—a year that had a ring to it. But what did I know about politics, except that aldermen could be bribed?

Sitting next to me on the beach with his knees up, Bob said casually, “I’m thinking of offering McCarthy secretary of state.”

“Gene or Joe?”

Bob’s laugh was short but explosive. “A dead secretary of state would be easier to handle.”

Even now Bob took heat over his time as a counsel on McCarthy’s infamous investigative committee; but he’d always stayed loyal to Tailgunner Joe, who was a longtime friend of the Kennedy family. Less well-known was that Bob had gathered the facts that guaranteed McCarthy’s censure by the Senate.

“With everything at stake,” I said, “you seem pretty cool-headed to me.”

“There’s a reason for that.”

“Oh?”

He was looking at the sea or maybe his kids or both. “Much as I dislike campaigning, it’s going well. I get a good feeling from the people—finally they’re not wishing I were Jack…or imagining I am him. I think I’m finally out of my brother’s shadow. Making it on my own.”

“You are, Bob. You really are.”

His eyes turned shyly my way. “Nate, I, uh…know we’ve had our differences. The, uh, Marilyn situation in particular. All the Castro nonsense. My judgment wasn’t always…well, I appreciate you putting that behind us. Still my friend. Helping me out.”

“Don’t work so hard,” I said. “I already stopped and voted on my way here.”

That Bugs Bunny grin. “Ah. But how did you vote?”

I allowed him half a grin in return. “That’s between me and my conscience. Of course you know what my conscience is.”

A nod brought his hunk of hair in front along with it. “That gun you carry. An ancient nine millimeter Browning, isn’t it?”

His look said he remembered the weapon’s significance: my father killed himself with it when I disappointed him by joining the Chicago PD and dancing the Outfit’s tune for a time.

“I think your father would be proud,” he said, “of how you turned out.”

“Not sure you’re right. But your father surely must be pleased.”

“Hard to tell. Hard to tell.”

The old boy’s ability to speak had been impaired since his stroke almost ten years before.

Bob’s eyes went to the sea again. “But, uh, about that conscience of yours. The artillery I mean.”

“What about it?”

“You still carry it?”

“I do.”

“I don’t want you doing that tonight.”

My laugh was reflexive. “Well, surely Bill Barry’s been packing all this time.”

“No.” The voice was firm, the blue eyes on me now, ice cold and unblinking. “I haven’t allowed it and he’s honored my request.”

“Well, I’m not about to!”

His chin neared his chest. “Look, there’s no way to protect a candidate on the stump. No way in hell. And if I’m lucky enough to be elected, there’ll be no bubble-top bulletproof limo like Lyndon’s using. What kind of country is that to live in? Where the President is afraid to go out among the people?”

I was shaking my head, astounded. “Jesus, Bob, what kind of morbid horseshit is that?”

He stared past me with a small ghastly smile. “Each day every man and woman lives a game of Russian roulette. Car wrecks, plane crashes, choke on a fucking fish bone. Bad X-rays, heart attacks and liver failure. I’m pretty sure there’ll be an attempt on my life sooner or later, not so much for political reasons but just plain crazy madness. Plenty of that to go around.”

I guess I must have been goggling at him. “If you think somebody’s going to take a shot at you—”

The blue eyes tightened. “I won’t have everyday people getting caught in my crossfire. Not for discussion, Nate. If you want out, I’ll understand.”

The girlish cries from the water’s edge turned suddenly into screams, shrill and frightened and punctuated with Mary’s “Daddy! Daddy!” while Courtney called out, frantic, “David’s in trouble!”

And the boy was too far out there, floundering, much too far, and Bob sprang to his bare feet and accidentally caused a wall of the sandcastle to crumble as he flew across the beach and ran splashing into the water and dove into the crashing waves.

The undertow had the child. His sisters were dancing in the surf again, but a wholly different dance now, fists tight and shaking. I got to my feet feeling as helpless as the young girls. So much tragedy had visited this family! Dread spread through me like poison.

I staggered to the edge of the beach where surf lapped, as if there might be something I could do. There was: the two children hugged me, sobbing, and I hugged back. Terrible moments passed, the waves roiling as if digesting a meal.

Then Bob and the boy popped up, the father having hold of his son, and wearing a vast smile in the churning tide. Both were on their feet by the time they reached the edge of the surf, the child coughing up water, the man bracing him, a scarlet red smear across Bob’s forehead from a cut over one eye. Both bore skinned patches here and there from where they’d gone down to the pebbly bottom in the water just deep enough to drown.

I was there to help but Bob smiled and waved me off, his arm around the boy as the little party trooped back toward the starkly modern white house, boxy shapes spread along as if spilled there, their many picture windows on the ocean like silent witnesses.

* * *

The interior of the Frankenheimer beach house was all pale yellow-painted brick walls enlivened by striking modern art, bright colors jumping. The living room and dining room were separated by framed panels of glass that added up to a wall. From the stereo came the Mamas and the Papas, Simon & Garfunkel, the Association, adding a soft-rock soundtrack. During the buffet lunch, the film director’s lovely brunette wife, actress Evans Evans, circulated slowly in a hippie print dress, making all their guests feel important, which they probably were.

Bob was buttonholed by several apparent political advisors I didn’t recognize as well as two Teds I did—his brother Edward Kennedy, who I’d never met, and Theodore White, the Presidential historian I’d seen on TV. The kids were on the patio with a college boy who’d been hired to look after them. The children, bored with eating, were fussing over David and his Band-Aid badges of courage.

Ethel, who I’d been told was pregnant but didn’t look it in her white sleeveless almost-mini dress, approached me with a smile, bearing a small plate of appetizers that didn’t seem touched. Her words didn’t go with her smile: “I suppose Bob told you not to carry a gun.”

“He did.”

She shook her head. “I wish you wouldn’t listen to him. He’s getting more and more death threats. I’m getting worried.”

“He’s stubborn about it.”

A weight of the world sigh was followed by a quick angry grimace. “He’s so darn fatalistic. Just resigned to accept what comes. Yesterday—in Chinatown, in San Francisco, in a convertible, as usual? A string of firecrackers went off and I thought they were shots and practically jumped out of my skin. I ducked down to the floor, just frozen. Bob? He just kept smiling and shaking hands. Barely flinched.”

She shook her head, laughed a little, and was gone. That may have been the worst laugh I ever heard.

A row of televisions had been brought in, and guests huddled around the screens after lunch to keep tabs on the sporadic network coverage; exit polls were coming in and the news was promising. Bob was not among the watchers.

I found him out by the circular pool, stretched between two deck chairs, napping. He looked like hell, a cut over his eye from the drowning rescue, as unshaven as a beachcomber. He was in another polo and baggy shorts and sandal-shod bare feet.

An easy mellow voice said, “Not the best image for our favorite candidate.”

I glanced to my right. John Frankenheimer—in a crisp pale yellow linen shirt, sleeves rolled up, and fresh chinos—might have been one of his own leading men. He stood a good three inches taller than my six feet, his black hair only lightly touched with white at the temples, his heavy eyebrows as dark as Groucho’s only not funny. We’d met but that’s all. He motioned me over to a wrought-iron patio set with an umbrella. I brought along a rum and Coke; he carried a martini like an afterthought.

“At least he cleans up good,” I said.

“He does. And takes direction.” He took a sip. “Or anyway he does now.”

“What do you mean he does now?”

His shrug was slow and expressive. “A while back, his guy Pierre Salinger flew me from California to Gary, Indiana, where Bob was speaking. To shoot a campaign spot. And I’m not cheap.”

“I believe you.”

“Bob said he only had ten minutes to give me, and I said then why fly me out from California? The result was awful—the camera caught his hostility. Later he called me at my hotel and asked if we could try again. I said we could if he gave me an hour and a half to show him how not to project cold arrogance. He took that on the chin, and I went over and did the spot fresh, and we’ve been friendly ever since.”

“He’ll need makeup for that cut.”

He studied his slumbering subject. “I’ll give it to him. Saved his son, I hear. He is one remarkable guy. Ever hear about how he taught himself to swim? Jumped off a boat in Nantucket Sound and took his chances.” Chuckled to himself. “Then when Bob and Ethel honeymooned in Hawaii, he saved some guy from drowning.”

“He should’ve been a lifeguard.”

“This country could use saving.”

I sipped. “You’re following the campaign with a camera crew, I understand?”

He nodded. “Yes, for a documentary but also to grab footage for more campaign spots. He’ll need both to beat Tricky Dick. You’ve known Bob a long time, I take it.”

“We go back to the Rackets Committee. And before.”

That seemed to confuse him. “You worked for the government, back then?”

“Not directly. I have a private investigation agency in Chicago. We have a branch here. The A-1.”

And that seemed to amuse him. “Oh, I know who you are. ‘Private Eye to the Stars.’ How many stories has Life magazine done about you, anyway?”

“Too many and not enough.”

His laugh was a single ha. “Too many, because it’s like James Bond. Him being a spy is an oxymoron.”

“Or just a moron. And not enough, because publicity is good for business. Do I have to tell a film director that?”

He gestured with an open hand. “Necessary evil.”

I leaned in. “John…your film The Manchurian Candidate? Stupid question, but…do you think that could happen in real life?”

His smile came slowly and then one corner of it twitched.

“Yeah,” he said. “I do.”

Bob was coming around.

“Star needs makeup,” Frankenheimer said, getting to his feet. “And better wardrobe.”

I needed to find a bathroom to put on my Botany 500 for tonight. I’d have to leave my nine millimeter Browning at the Ambassador desk to be locked in their safe. When I emerged I found Bob looking similarly spiffy in a blue pin-striped suit and white shirt. Frankenheimer was in the process of expertly daubing stage makeup on the candidate’s scraped, bruised forehead.

In the background, Ethel was giving orders to that college kid to deliver her children to the Beverly Hills Hotel, where they rated two bungalows to my measly one. We would be driven by Frankenheimer to the Ambassador and Ethel, not ready yet, would follow in another vehicle.

The film director’s car turned out to be a Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud. Even though I had made Life a couple of times, this would be my first ride in one. Frankenheimer, who’d seemed so cool before, betrayed himself otherwise on the Santa Monica Freeway with his bat-out-of-hell driving. When he accidentally raced right by the Vermont off-ramp and got snarled up in the Harbor Freeway exchange, he swore at himself and pounded the wheel.

“Take it easy, John,” Bob said from the backseat. “Life is too short.”

TWO

At just after seven, Frankenheimer was tooling his silver Rolls along Wilshire, his enthusiasm behind the wheel curtailed by downtown traffic and red lights. Bob and I, a couple of his advisors opposite us in the limo seats, watched Los Angeles slide by like postcards. With the sun still up but heading down, this was what the movie people called Magic Hour, when dusk painted the City of Angels with a forgiving brush. Young people owned the sidewalks, college kids in preppie threads, hippies friend or faux in huarache sandals, boots motorcycle or cowboy, hair straight, curly, shoulder-length or longer (as the song went), Quant cut or rounded Afro. Minis on the go-go, would-be rockers in Cuban heels, heads bobbing with beaded bands, hooped earrings, rainbow colors (clothes and people), peace signs and raised fists, nothing quite real in a twilight where the fireflies were neon. Times they were a changing, and the man in back next to me seemed to be wondering where he fit in.

“Your people, Bob,” I said.

“Some of them. McCarthy has the A and B students. I have to settle for the rest.”

At left the Brown Derby’s giant bowler, half-swallowed by its mission-style expansion, squatted on a corner. Our destination was at right, past a white obelisk looking like a pillar of salt left behind by God in an Art Deco mood—

A

M

B

A

S

S

A

D

O

R

HOTEL

—with a bronze statue of a scantily clad goddess at its base posed, they say, by Betty Grable.

On a city block’s worth of landscaped grounds between Wilshire and West Eighth Street, at the end of an endless drive, sprawled the Ambassador, a city within the city. Its twenty-four unlikely acres in downtown L.A. included tennis courts, Olympic-size pool and golf course. Eight coral-colored stories spawning wings were home to twelve-hundred-some rooms, restaurants, movie theater, post office, beauty and barber salons, shop concourse and the palm-swept rococo Cocoanut Grove, where Rosemary Clooney was headlining.

From its Jazz Age beginnings, including half a dozen Academy Award ceremonies until well after World War II, the Ambassador had been Hollywood’s favorite movie-star haunt—from Harlow, Gable and Crosby to Marilyn, Sinatra and Lemmon. But in an era where Jane, not Henry, was the reigning Fonda, the Ambassador seemed about as up to date as when Charlie Chaplin was in residence.

Still, it didn’t seem like anything could kill the old girl. In these times, the Ambassador depended on tourist trade, business seminars and political events—tonight, in addition to the optimistic Kennedy campaign’s planned victory celebration, were two election night parties, Democrat Alan Cranston and Republican Max Rafferty for nominations in the upcoming Senate race.

Frankenheimer drove around to a rear door off the Cocoanut Grove’s kitchen, parked back there and said he needed to check on the guerrilla film crew he’d positioned in the Embassy Room. The rest of our little group went up the freight elevator to the fifth floor, where Bob and Ethel had been staying in the Royal Suite during the California campaign. Tonight two more rooms had been added, 511 across the hall, a war room for aides and advisors, and 516 for invited press, down the hall a ways.

I stayed near the candidate, either at his side or just behind him while he dropped by the press room where he smiled in his shy way, shaking hands here and there. The twenty-five or so journalists packed into the room, which had been cleared of its bed, included some of the most famous in the country—Pete Hamill of the New York Post, columnist Jimmy Breslin, Jack Newfield of the Village Voice, and that unlikely patrician sportswriter George Plimpton.

The smoke was no thicker than the fog had been over the Pacific this morning, and the rumbly murmur of voices trying to be heard might have been Jap planes making a comeback. A small open bar had been set up to accommodate the large gathering, doing a mighty business.

Breslin and Hamill somehow managed to buttonhole Bob. Both knew me a little and granted me the kind of nod a New York celebrity grants a Chicago nobody, and started in telling the candidate what he needed to do to win in New York. Youthful Hamill, with a shock of reddish red hair to rival Bob’s brown mop, grinned and smoked and leaned in aggressively, like an off-duty Irish cop.

“You better score a knockout tonight, champ,” Hamill said, “if you wanna make a dent in all this anti-you shit.”

Bob chuckled but his eyes were already weary. “What is all this New York animosity about, anyway? My guys say it’s going to be a bloodbath.”

Hamill grinned like the Cheshire Cat. “Face it, Bob—New Yorkers are haters! They can work up an unbelievable amount of bile. They resent wakin’ up in the morning.”

Breslin, a fleshy-faced bulldog who always seemed half in the bag, leaned in, raving, ranting. “It’s the goddamn Jews! Ya gotta get through to the Jews if you want a shot!”

Trying to conceal his distaste, Bob swept back his bangs and said, “Personally, I’d like to get through to the New York Times,” and excused himself and we got out of there.

Right across the hall from the Royal Suite, 511 was almost as packed as the press room, in this case with aides in no-nonsense work mode. No bar in here but plenty of cigarette smoke, and little phone stations had been set up everywhere, with a bank of three TVs against one wall. The overall murmur was muffled out of respect to those on the phone. In this nearly all-male room, a sea of rolled-up white shirts and a few suits of campaign spokesmen, those not phoning were huddled in little groups, strategizing. Frank Mankiewicz, Bob’s campaign press secretary, seemed in charge of what reminded me of a wire room.

Mank, who I’d met a few times, was a former journalist whose late father had written Citizen Kane, the most famous newspaper movie of all. I wasn’t sure if that was ironic or just fitting. Someone once described Mank as a rumpled little guy who might have been a used-car salesman, but his dark eyes were as shrewd as they were sad and his high forehead seemed to tell you a good-size brain resided.

“Good,” Mank said to Bob, “you’re here. I’ve got Senator McGovern on the line. He’s got excellent news for you from South Dakota.”

Bob went to a nearby phone and I stayed back with the press secretary. I asked him why he wasn’t with the journalists.

“Half the time I am,” Mank said. “But this room is even more important. We’re feeding the media that didn’t make the trip. Look, uh, Nate, make sure Bob spends time on a speech. When he wins tonight, and goddamnit he will, every network will be covering him. That victory speech needs to sing. He’ll listen to you.”

“You do know I’m just a bodyguard. And not even allowed a gun.”

Mank touched my suitcoat sleeve. “He likes you.”

“Why?”

“Two reasons. You never kiss his ass. And you never ask about his brother.”

Bob came back smiling, raising a fist chest high. “More votes than McCarthy and Humphrey combined. Got both the farmers and the Indians. Carried some of the Indian precincts one hundred percent!”

A smile was buried somewhere in Mank’s furrowed puss. “Exit polls say the same about the blacks and Mexicans.”

Bob nodded and his smile faded. “If I could just shake loose of McCarthy. I shouldn’t be on street corners in Manhattan begging for votes when I could be chasing Humphrey’s ass all over the country.”

“Ass” was unusually salty language for Bob.

“Bob,” Mank said through a battle wound of a smile, “I told you this would be an uphill struggle.” Then he patted his candidate on the shoulder and went back to work.

Next stop was the Royal Suite, entering into the expansive sitting room, a celebrity cocktail party where laughter rose like bubbles in a glass. The maybe one hundred supporters, stuffed in the space with its own bank of TVs and bar, were blissfully unaware of the frustration their hero was suffering on a night that seemed headed to victory.

The eclectic mix encompassed L.A. Rams tackle Rosey Grier and decathlon champion Rafer Johnson, astronaut John Glenn and Civil Rights activist John Lewis, labor leader Cesar Chavez and comedian Milton Berle. Plenty of Kennedy people, too, including Pierre Salinger and Bob’s sisters Pat Lawford and Jean Smith with her husband Steve, a trusted RFK confidante. Others were familiar but I couldn’t connect with names. No sign of brother Ted, though the four Kennedy kids from out at Malibu—David, Michael, Courtney and Mary—were winding through the crowd as if in a garden maze, in pursuit of waiters with trays of hors d’oeuvres.

This was where Frankenheimer had wound up, chatting with a guy with white curly Roman hair and black eyebrows; Bob said this was On the Waterfront screenwriter Budd Schulberg. Listening politely, cocktail in hand and trying not to look bored, was a slender curvy beauty about forty. For a moment I thought she was the film director’s actress wife, but no. Her flipped-up, lightly sprayed brunette bob was maybe too young for her, but there were worse sins. She looked familiar to me, or was that wishful thinking?

Frankenheimer, like everybody else, had noticed Bob come in and motioned for him to come over. As his appendage, I made the trip.

We said quick hellos minus any introduction of the brunette, who was either famous enough that I should have known her or dismissed by these two chauvinists as window dressing. But she had a nod and a pink lipstick smile that encouraged me to ignore the twenty-year gap between us. My self-esteem went up.

So did Frankenheimer’s eyebrows, as he gestured Nero-style with a downward thumb. “Bob, I checked out the Embassy Room—must be nearly two thousand people crammed in. Security guards and fire marshals are routing the overflow into the ballroom downstairs. I wish the fucking networks would declare a winner—the natives are getting restless.”

“With these new computerized voting machines,” Bob said, “you know it’s going to be damn slow. Could be midnight before we know.”

The director shuddered. “Hope to hell you’re wrong. It’s stifling down there. People may start passing out. And frantic! Chavez has a marimba band going at times. At least I’m getting good footage—lots of cute girls in straw hats, white blouses, blue skirts, red sashes. Chanting ‘Sock it to me, Bobby.’”

“Well, that’s embarrassing,” he said with a shudder.

The brunette spoke for the first time. “For the record, I did not wear a straw hat for the occasion, or a sash.” She did have a white blouse on, silk, and a navy skirt, short but by no means mini.

Bob gave her a half-smile. “I never dreamed you had, Miss Romaine.”

Now I remembered her.

I noted that she seemed at ease in front of the candidate; being here made her somebody in the campaign.

Schulberg was saying, “If you win big tonight it’ll be thanks to black and brown people. Don’t forget that, Bob, if you find yourself making a victory speech. You’re the only white man in this country they trust.”

“If Drew Pearson hasn’t changed that,” Bob said glumly, referring to a column that laid the Martin Luther King wiretap at his feet.

Frankenheimer said, “Bob, what’s this about me going up with you on that postage-stamp stage for your big speech? You don’t want to be seen with me!”

Bob gave him the “What’s Up Doc?” grin. “I can’t be too particular, campaigning.”

“A Hollywood director standing next to you on that dais is lousy for your man-of-the-people image. Surround yourself with Chavez and that guy from the Auto Workers, Schrade. Best I just wait back behind the stage till you finish.”

Bob thought about that for a second, then said, “When I say, ‘Let’s go on to win it in Chicago,’ or something to that effect, you go collect your Rolls. Wait for us by the kitchen, then drive us to the factory.”

“What factory?” I asked.

“The Factory,” Frankenheimer said, addressing the slow student in the classroom. “Nightclub over on North LePeer that Salinger has a piece of.” To Bob he said, “I’ll have a table waiting for you and Ethel with Roman Polanski, Sharon Tate, Jean Seburg, Andy Williams…”

The glittery list went on. How did Bob’s man-of-the-people image fit in with jet set hobnobbing and riding around in a Rolls-Royce?

Misreading me, Bob said, “You can skip the nightclub baloney if you like.”

“That,” I said, “is exactly the kind of place you need a bodyguard.”

The brunette, who’d been taking all this in, flashed me a chin-crinkly smile and said, “Who do you think you’re fooling, Nate? You just want to meet Sharon Tate.”

So she remembered me, too.

“Well,” Bob said to me, almost irritated, “I don’t need a bodyguard here. I’m obviously among friends. I’m going across the hall to check on Ethel and maybe get away from this madness for a while.”

I fell in after him, but he turned and raised a warning forefinger, then wound through the bodies casting smiles and nods like manna to the masses, and went out.

I turned and Frankenheimer was gone. Schulberg, too.

That left the brunette, whose cocktail glass was empty.

“Let me get that freshened for you,” I said, wanting to be useful to somebody.

“Sure. Ginger.”

“And what, seven?”

“No. Ginger and ginger.” Her very dark brown eyes flicked with amusement in their near Cher setting. “You don’t remember me, do you?”

“Sure I do. You’re on TV.”

“Guilty. Just guest shots and bits. Never did land a series for all the pilots I shot.”

“In the war?”

Her laugh was nice, throaty but feminine. “I fought a different war than you.”

We were threading through the rolled-up white shirt sleeves toward the bar where a Chicano guy in a tux jacket was making drinks for a steady crowd and wishing he were anywhere else.

“I Dream of Jeannie,” I said. “Harem girl, right? Bewitched. Salem-style witch, only glamorous?”

Her mouth was wide, in a nice way; it widened further in a smile no whiter than a Bing Crosby Christmas. She said, “You don’t look like somebody who watches that kind of pap.”

“If the pap has Barbara Eden or Elizabeth Montgomery in it, I’ll lower myself. Now, if you had a juicy role on a McHale’s Navy, I’d never know.”

We were in line at the bar.

“I’ve been on that and worse,” she confessed. “Now, you? You look more like the Have Gun—Will Travel type.”

I wished I were traveling with a gun. “Maverick’s more my style.”

The cat eyes narrowed. “Weren’t you a consultant on Peter Gunn? Wasn’t that based on you?”

“That’s the rumor. And I do remember you, Miss Romaine. Nita. But not entirely from situation comedy appearances.”

It had been a good five years, and only that one evening. A very nice evening though. Ships that docked in the night.

We were at the counter now and the bartender gave Nita her ginger ale and made me a rum and Coke; and I made a friend forever stuffing a five spot in his tip jar.

The chairs and couches were long gone but we found a corner to sit in, on the floor, like kids at an after-prom party. She sat with her knees up and a lot of her pretty tanned nylon-free legs showing. Like we said in the service, nice gams. They probably still said that on McHale’s Navy.

“I’m hoping,” she said, after a sip of her ginger ale, “that you remember me for more than my TV walk-ons. Neither Barbara nor Elizabeth are big on giving other girls much airtime.”

“Guess I haven’t seen you turn up on the tube lately,” I admitted. “But you’re still acting?”

The eyes were big and brown; the Cher makeup was overkill, as naturally lovely as she was. “My agent claims I am. Calling myself a ‘girl’ is a little sad, don’t you think? I’m at that age where casting directors say nice things that don’t include, ‘You’ve got the part.’”

“You look young to me.”

“Sure. But you’re, what? Sixty?”

A gut punch but I still managed to laugh. “Maybe, but then I never claimed to be a ‘boy.’”

“Oh, I know you’re a boy. I remember Vegas even if you don’t.”

I shrugged. “My memory is pretty good for a man of my advanced years.”

It had been a JFK campaign event. She’d been heading up the Young Professionals for Kennedy. I asked her if she was doing the same thing for Bob.

“Not quite. I’m attached to the Kennedy Youth campaign. Kind of a den mother for the actual girls out fundraising. I help with secretarial work, too. When you’re an actress in this town and don’t care to wait tables, typing a hundred words a minute comes in handy.”

Smoke drifted overhead forming a cloud that promised no rain, despite the room’s pre-thunder murmur.

“About Vegas,” she said.

“What about Vegas?”

“I was a little drunk.”

“Not on ginger ale you weren’t.”

“Well, I wasn’t drinking ginger ale. Tonight is work, so I’m not drinking. What I mean about Vegas is…uh…I’m not always that easy.”

“Oh, hell, I am,” I said.

That made her laugh.

“Or anyway,” I said, “I used to be, before I got so elderly.”

Her mouth pursed up like a kiss was coming, but it was a promise not kept. “I bet you still do all right with the ‘girls’—or maybe the ladies. Are you married, Mr. Heller?”

“No. Why, don’t you keep up with my press?”

She put a hand to her bosom. “No, I’m sorry, since the acting roles slowed I’ve had to cancel the clipping service.”

I shrugged. “I can catch you up easy enough. I have one ex-wife and one son who, this morning, said ‘Fuck you, Dad,’ because he’s for Eugene McCarthy. How about you?”

“No children. One ex-husband. I’m fussier about husbands now. I’m looking for a prospect about, oh, sixty, who is very well-fixed. What they used to call a sugar daddy.”

I nodded sagely. “You know, I have certain connections at a prosperous private detective agency. I could arrange a bargain rate for locating such a rare catch.”

We sat and talked that way for a while. We laughed quite a bit. I didn’t recollect her being that funny back in Vegas, but then she admitted being tight that night. I said that’s just how I remembered her, with a sexual tinge that got me playfully slapped on the sleeve. I did not tell her that I also recalled how beautiful she had looked naked with neon-mingled moonlight coming in the windows of my Flamingo bedroom.

Barbara Eden and Elizabeth Montgomery who?

About then I noticed the guy ordering over at the bar—about five-eight, average build, in gray slacks and a dark sweater over a button-down white shirt on this hot June night. Tan with curly bushy black hair including sideburns, his eyes striking me as both furtive and sleepy. Two PRESS badges clipped together around his neck with what I recognized even at a distance was one of the PT-109 tie clips that Bob and his people sometimes handed out.

“You need another refill?” I asked Nita as I got to my feet. She didn’t, and I added, “Well, save my place. I need to freshen mine.”

Other than the guy in the sweater with the double press passes, the bar was in a momentary lull. I stepped up just as the Chicano bartender announced, “Scotch and water, sir,” handing a glass to his curly-haired customer.

Conversationally, I asked, “What paper?”

“Uh, pardon?” He blinked at me, hooded eyes going suddenly wide.

“What paper are you covering this for?”

“Uh…freelancer. Something this important, you know, someone will want it.”

“You have any I.D. you can show me, besides those press passes?”

“Who’s asking?”

“Senator Kennedy’s security chief. Let’s see your I.D.”

He smiled nervously. “Okay, you got me.”

“Have I.”

“I’m just a fan. Bluffed my way in. Snatched a couple of passes. So sue me.”