6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

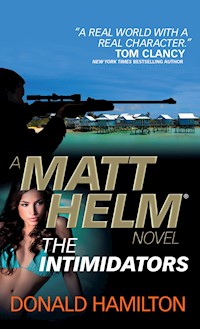

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

It was a double mission this time. Firstly, to terminate a top-notch enemy agent. Secondly, to locate the missing fiancée of a Texas oil millionaire, lost in the Bermuda Triangle. Somehow these two cases were connected, but it wasn't clear how until more high-profile types disappeared. They weren't dead, just part of a deadly little game...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by Donald Hamilton

Title Page

Copyright

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

Also by Donald Hamilton and available from Titan Books

Death of a Citizen

The Wrecking Crew

The Removers

The Silencers

Murderers’ Row

The Ambushers

The Shadowers

The Ravagers

The Devastators

The Betrayers

The Menacers

The Interlopers

The Poisoners

The Intriguers

The Terminators (June 2015)

The Intimidators

Print edition ISBN: 9781783293001

E-book edition ISBN: 9781783293018

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: April 2015

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 1974, 2015 by Donald Hamilton. All rights reserved.

Matt Helm® is the registered trademark of Integute AB.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers.

Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website:www.titanbooks.com

1

It was a good day, until we got back to the dock and found the messenger waiting. I didn’t know he was a messenger when I saw him, of course. We seldom do, until they identify themselves. He was just an ordinary-looking man, for the Bahamas, black, rather shabbily dressed, chatting with one of the marina employees as he watched our captain back the fifty-foot twin-screw sportfisherman into its narrow slip, making the complex maneuver look as if it were so easy that even I could do it if I wanted to try, which I didn’t.

I was standing aft in the open cockpit beside the fighting chair, wondering if I was supposed to be performing some useful operation with the stern rope—excuse me, line—since the mate was busy forward. As you’ll gather, I’m not the world’s greatest nautical expert. Then the marina gent on shore stepped up and gestured toward the line in question. I handed it to him. As he dropped the loop over one of the big dock cleats, his companion caught my eye and made a small signal, never mind what.

That was all. The next moment, the unknown man was strolling away casually along the pier, stopping to talk with another black man near the marina office, and I was trying to secure the dockline I was holding, a duty from which I was relieved by the young mate.

As I said, it had been a pretty good day up to that point. We’d raised two sailfish and connected with a blue marlin in the three-hundred-pound class. Probably because of my total inexperience, we’d missed both sails, and the big boy had managed to wrap the wire leader around his bill, snap it, and get away. Nevertheless, I’d had him on for about fifteen minutes, all three hundred pounds of him, and for an ex-freshwater-angler, brought up on little ten-inch trout, the whole experience had been fairly memorable. You might say I was the one who was hooked.

I’d discovered that, for a man in my line of work, deep-sea fishing has considerable advantages as an off-duty sport. Trolling or casting on the average inland lake, you’re often within easy rifle shot of shore; wading a brushy stream, fishing rod in hand, you’re almost always a beautiful target for anyone lurking in the bushes. On the ocean, on the other hand, you’re reasonably safe from hostile attention. Once you’ve checked out the boat, and sized up the crew, and your fishing companions if any, you can relax and forget about watching your back. Unless somebody considers you important enough to send a submarine after you—and I don’t flatter myself I’ve made anybody quite that mad—nothing’s going to sneak up on you unexpectedly on a small vessel ten miles at sea.

Besides, I’d just learned, fighting a truly big fish is a hell of a lot of fun; and the rest of the time you can lean back lazily in the fighting chair watching the baits skipping astern, soaking up the sunshine, and carefully forgetting about various things including a nice lady named Laura, a colleague who’d been called back to work some weeks ago after we’d spent a pleasant Florida interlude together. Well, I guess she wasn’t a nice lady by ordinary standards—there are no nice people in our business—but I’d found her an attractive and enjoyable companion despite certain strong-minded Women’s Lib tendencies.

Now it was my turn to receive the summons to action. I reviewed the situation hastily. Loafing around the Florida Keys alone after Laura had left, doing a little desultory angling, I’d run into a fairly prominent Texas businessman and sportsman, a gent reputed to have a finger in various political pies, who seemed to think I’d done him a favor. I’d barely been aware of his existence when he approached me, and he must have had very good Washington sources of information—perhaps a little too good—to know about me and the assignment I’d recently completed, a job with political overtones. It had been a cooperative venture, anyway, with a lot of agents involved. Nevertheless, the success of our mission had apparently saved Big Bill Haseltine’s bacon in some way and he’d been aching to show his gratitude to somebody and I’d been elected. He’d insisted on arranging for me to spend a week learning about real ocean fishing at a private club where, he’d said, the billfish were so thick you hardly dared go swimming for fear of being accidentally perforated by a passing marlin or casually skewered by a sail.

Walker’s Cay—pronounced key just like in Florida—is the northernmost inhabited point in the Bahama Islands which, in case you didn’t know, were part of a foreign country or possession called the British West Indies, or B.W.I., lying at its nearest some forty-odd miles east of Miami. I hadn’t known, and it came as a big surprise to me. Somehow, never having been there, I’d had the vague impression that the Bahamas were located way down south of Cuba in the Caribbean somewhere, or maybe far out east in the Atlantic in the neighborhood of Bermuda.

Actually, Walker’s Cay, although off to the north a bit, turned out to be barely an hour’s plane ride from the airport at Fort Lauderdale, just up the Florida coast from Miami. The plane was a clumsy-looking and not very speedy flying boat, a private craft belonging to my hosts-to-be. Rather to my disappointment, it didn’t sit down on the water upon arrival but put down its wheels again and landed on the paved strip that took up a large part of the little island. The rest of the limited real estate was mostly devoted to the clubhouse with its grounds, swimming pool, cottages, and service buildings; and by the marina and its facilities. To let us know we were really landing on foreign soil, there was a black Bahamian customs gent to greet us; but we’d already filled out the simple entry form on the plane, and the pilot took care of the rest of the formalities…

All that seemed longer ago than yesterday morning. After a day and a half on the water, I’d got into the swing of this angling existence, and all I’d had on my mind until a moment ago was fish. Now I had to figure out how to get out of here quickly without causing comment, and locate a moderately safe phone, and call Washington. What I’d just received was the “make contact at once” signal, which implies reasonable dispatch but also reasonable concern for security. There’s also the simple “make contact” signal, which says take your time and be absolutely certain you don’t attract attention and aren’t being watched; and then there’s the “make contact with utmost haste” signal, which means drop everything and grab the nearest phone regardless.

I went through the motions of thanking the captain and mate for a fine day, but my thoughts were elsewhere. I hoped they didn’t notice; they’d been very considerate to a clumsy beginner at the sport. Stepping ashore, I couldn’t help feeling a slight resentment. This was unreasonable. Certainly there had been times when I’d been snatched back to work unceremoniously after being promised a lengthy leave, but this wasn’t one of them. I’d had most of the summer free; I was in no position to complain. Nevertheless, I couldn’t help wishing that I’d either managed to land that big marlin this afternoon, or that Mac had held off a day or two and let me hook into another one.

I walked along the pier and up the hill past the swimming pool to the main building, and went into the office to do a little research on the problem of communications. The telephone company does not, of course, run its wires to islands a hundred miles out in the Atlantic. I knew the club had radio facilities—you could see the mast far out at sea—and kept some kind of schedule. I knew they could probably, therefore, get me any number in the U.S. by way of the nearest marine operator on the mainland. However, since any radio-equipped boat between here and there could presumably listen in, it seemed like a hell of a public way of chatting with Washington on subjects that would probably prove to be very private indeed.

I was selling Mac short. He’d taken care of everything. The girl at the desk, a slight, friendly looking redhead with freckles, looked up quickly.

“Oh, Mr. Helm,” she said. “Any luck today?”

“We hooked a good-sized blue but I couldn’t bring him in,” I said.

“Oh, that’s too bad,” she said. “I mean, it’s really too bad, because I have a message for you from Mr. Starkweather, Jonas Starkweather, editor of Outdoors Magazine. It just came in. He’s going to be in Fort Lauderdale tomorrow night and he would like you to have dinner with him. He says it’s important, something about some pictures he needs very badly.”

At an earlier period in my life I’d made my living with a camera, with an occasional assist from a typewriter. It was a cover we still used upon occasion; but it was unlikely that any magazine editor remembered my name at all, let alone favorably enough to buy me a dinner. Nevertheless, I might have considered the possibility if the man at the dock hadn’t prepared me for some devious, secret-agent-type shenanigans.

“Damn!” I said. “There goes my fishing trip! Did he say where and when?”

“The rooftop restaurant of the Yankee Clipper Hotel at seven o’clock tomorrow night. He’s staying there and he’s reserved a room for you. I’ve put you down for the plane tomorrow, if that’s all right, Mr. Helm. You should be down here with your luggage a little before ten…”

Flying over the island the following morning, I could see the big white sportfisherman lying idle in its slip in the marina; and I knew a twinge of regret, which was ridiculous. Spending a lot of time and effort catching an enormous fish you weren’t even going to eat was actually an absurd sport, I told myself firmly. It wasn’t as if I needed the excitement. Mac would provide me with plenty of excitement, I was quite certain. He always did.

I didn’t speculate on what form it would take. I just sat and watched the subtle, shifting colors—all shades of blue and green, with an occasional touch of weedy brown—of the shallow water below. We were crossing the extensive Little Bahama Bank, so called to distinguish it from the even larger Great Bahama Bank farther south. There was a tiny islet or two, none as big as Walker’s Cay; and then we passed the tip of the much larger island of Grand Bahama. Although big enough that only a fraction of it could be seen from the plane—the fourth largest island in the Bahamas, I’d been told—it didn’t look very high, and I couldn’t help thinking that, judging by the little I’d seen, if the whole area should sink a few feet into the sea, there’d be nothing left but some nasty submerged reefs. On the other hand, if it should rise just a little, there’d be the biggest land-rush of the century, to a brand-new subcontinent just off the coast of Florida. Undoubtedly developers and promoters somewhere were already hard at work on the problem of jacking up all those endless, beautiful, lonely, useless, watery flats just far enough to turn them into valuable real estate on which to build their lousy little houses and golf courses.

Soon we were out over the violet-blue Gulf Stream—a thousand feet deep, I’d been told—and shortly we were landing at the Fort Lauderdale airport. Customs inspection was, for U.S. Customs, surprisingly fast and considerate, at least compared with the last inquisition to which I’d been subjected, returning from Mexico. Maybe nobody grows poppies or grass or coca leaves in the Bahamas. It was nice to know that returning to your native land could be made so simple and pleasant; but it kind of made you wonder if it was really a worthwhile endeavor, delaying and humiliating millions of honest, upright, martini-drinking Americans at their own borders, elsewhere, just to save a few people from one particular bad habit.

I guess the prospect of going back to work after a couple of months of leisure was making me philosophical. There were no messages for me at the Yankee Clipper Hotel, a narrow, seven-story hostelry on a wide, white beach that was visible from the window of my third-floor room. I could also see a couple of sailboats far out in the blue Gulf Stream that I’d just flown over; and some powerboats closer to shore where the water was paler. The bellboy showed me the view and the TV set and the bathroom. I gave him a buck and a thirty-second head start, caught the next elevator down, and ducked into a lobby phone booth I’d spotted on my way in.

“Eric here,” I said when Mac came on the line.

“Pavel Minsk,” he said. “Reported heading for Nassau, New Providence Island, B.W.I. Find out why, and then make the touch. Mr. Minsk is long overdue.”

“Yes, sir,” I said.

2

I didn’t like it. It was the usual cheapie Washington routine, trying to get double mileage out of a single agent. It wasn’t enough that one of the other side’s big guns, a man we’d been after for a long time, had at last been spotted out in the open where we might be able to move in on him. That didn’t satisfy the greedy gents from whom Mac got his instructions, although they’d been screaming at us for years to do something drastic about this very individual—well, if it could be managed discreetly, that is.

Now that we at last had the target in view, or would have shortly, I was supposed to stall around playing superspy and learning just why he’d come out of hiding before I moved in on him. It was kind of like going after a man-eating tiger with strict orders to determine exactly which native the big cat planned to make a meal of next, before firing a shot. I mean, there was really no doubt about why Pavel Minsk—also known as Paul Minsky, or Pavlo Menshesky, or simply as the Mink—was going to Nassau, if he was really heading that way. Outside his own country, the Mink went places for just one reason. The only question was who.

I was tempted to ask Mac why the hell the high-up people who wanted information so badly didn’t send one or two of their own intelligence-gathering geniuses to handle that end of the job. They were supposed to be good at it, and information wasn’t exactly my business. They could call me in to exercise my specialty when they were through working at theirs. I didn’t ask the question, because I already knew the answer. Various intelligence agencies had already lost too many eager espionage and counterespionage types to the Mink. He hunted them the happy way a mongoose hunts snakes. The bureaus and departments concerned didn’t want to risk any more nice, valuable, well-trained young men and women in that dangerous neighborhood. Just me.

“Yes, sir,” I said grimly. “The British Colonial Hotel. Yes, sir.”

“You will be briefed on the background at dinner this evening,” Mac said. “Just keep the engagement arranged for you.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You don’t sound pleased, Eric. I should think that by this time you’d be bored with inactivity and happy to have some work to do.”

He was needling me gently. I said, “It kind of depends upon the work, sir.”

“If you don’t feel up to dealing with Minsk…”

I said, “Go to hell, sir. You know damned well the Mink rates just about as well as I do by anybody’s scoring system. We’re both pros in the same line of business, and if I may say so, pretty good pros at that. That means it’s a fifty-fifty proposition, or was. But if I’m supposed to snoop around playing invisible tag with him for a couple of days before I make the touch, the odds in his favor go a lot higher.”

“I know. I’m sorry. Those are the orders. You are at liberty to turn them down.”

“If I did, you’d send some other poor dope to do the same job under the same crummy conditions, maybe Laura, and I’d be responsible for getting them killed. No, thanks.”

“As a matter of fact, I did have Laura in mind as an alternate,” Mac said calmly. “She should be back in this country shortly.”

“Sure. And if my mother was alive, you’d use her, too.”

It was a rough game we played after years of association. He’d started it; now he ended it by saying: “The British Colonial Hotel, Eric. I’ve told you how and when to get in touch with our local people. Minsk arrives the day after tomorrow, according to our information, which may or may not be correct. You can use the time to familiarize yourself with the city. I don’t believe you’ve been there. And remember, we want no international incidents. Discretion is mandatory.”

“Yes, sir. Mandatory. Question, sir.”

“Yes, Eric?”

“Do I stop him or don’t I?”

“What do you mean?”

“You know what I mean, sir,” I said. There are times, even when dealing with Mac, that you’ve got to remember that bureaucrats are bureaucrats the world over, and you’ve got to pin them down. “Do I do my job before or after he does his?”

“You’re assuming that he’s coming to the Bahamas on official business?”

“The record says he never sticks his nose out of his Muscovite sanctuary for anything else.”

Mac hesitated. Then he said, “I think it would be nice, on general principles, if Mr. Minsk’s last job should be a failure. However, it is not of critical importance. Fortunately, we have no instructions to cover the point; and we are not a fine, humanitarian organization like the Salvation Army. I’ll leave the matter to your judgment, Eric.”

“Yes, sir.”

After hanging up, I realized that I’d forgotten something I’d meant to ask him. Earlier, I’d requested a check on William J. Haseltine, the Texas tycoon who’d been so anxious for me to go fishing at Walker’s Cay. I mean, it’s a nasty suspicious racket in a nasty suspicious world; and when a friendly person hands you a candy bar out of the goodness of his heart, your first act, if you’ve been properly trained, is to check it for cyanide. Big Bill might be exactly what he’d seemed, a wealthy Tejano who liked to pay his debts, but then again he might not. Well, if our research people had turned up anything interesting, Mac would have told me.

Or maybe not. It occurred to me that it was kind of coincidental, my being handy in the Bahamas, where I’d never been before, at just the time Mr. Pavel Minsk decided to pay a visit to Nassau, or somebody decided it for him. I don’t have a great deal of faith in coincidences like that. I warned myself that I’d better watch my step even more carefully than I normally would, dealing with a high-ranking fellow-pro, since it was possible that big mysterious things were afoot in that foreign island area just off the Florida coast; and that brilliant executive characters in Washington and elsewhere were surreptitiously shifting people like the Mink and me into striking position, like pieces on a chessboard.

At this stage of the game, if it was a game, everybody would be feeling very clever indeed, initiating supposedly infallible undercover gambits with sublime confidence. A little later, after a few unexpected reverses on both sides, everything would fall into hopeless confusion, and it would be up to the remaining pawns and pieces on the board to figure out what was supposed to be going on, and play out the contest on their own, judiciously disregarding panicky directives fired at them by rattled superiors totally out of touch with the situation in comfortable offices thousands of miles away.

I don’t mean to imply that Mac ever gets seriously rattled. He’s not that human. As far as I know, he never gets rattled at all. However, there are always political hacks in the upper hierarchy who have to change into rubber training-pants whenever the international going gets rough, meanwhile stammering out frantic, incoherent orders that Mac is obliged to transmit.

I was early for my seven o’clock dinner engagement, deliberately. I’d been given no indication who Mr. Jonas Starkweather was or what he looked like, and nobody’d arranged for us to wear white carnations in our buttonholes. Since I didn’t know whom I was looking for, and he presumably did, I wandered into the cocktail lounge adjacent to the dining room fifteen minutes ahead of time, ordered a martini, and sat at a window looking down at the beach seven stories below, and the blue Atlantic Ocean, and the boats.

The funny thing was, I reflected a bit grimly, that I was supposed to be kind of an expert on boats these days, having stumbled through a few assignments involving watercraft of one kind or another—generally with lots of help from real sailors who happened, luckily for me, to be involved. Actually, I’d been born in the approximate center of the continent and hadn’t been formally introduced to salt water until, early in my present career, I was run through a quickie training course at Annapolis designed for agents who might have to know a little about getting on and off a foreign shore.

However, you get typed very quickly in this business just as in any other. Do a good job once or twice with high explosives or a submachine gun and you suddenly discover that you’re the resident big-bang or chopper expert. I had a hunch that, since my last watery assignment had turned out pretty well, I’d kind of automatically become Mac’s nautical specialist, the man to be called upon whenever action afloat could be expected; and that this was at least one reason why I’d been picked for this job in the Bahamas, which are mostly water. It wasn’t a reassuring thought, and I decided that if I had time in the morning before catching my plane to Nassau, I’d better hunt up a bookstore and get myself a copy of a large volume entitled Chapman’s Piloting, Seamanship, and Small Boat Handling which, I’d been told, is the basic reference work for all aspiring small-boat sailors…

“Matt! It’s been a long time!”

I looked around quickly. Two men stood above me. The one I didn’t know was the one who’d spoken: a tall, thin, stooped individual with hornrimmed glasses, obviously—maybe a little too obviously—an editor bent by years of labor at desks full of manuscripts. Actually, he was probably a good man with a gun, at least a fair hand with a knife, and maybe even something of a judo or karate expert. The tweedy, intellectual look was, however, quite convincingly done. I got up and stuck out my hand.

“Jonas!” I said. “My favorite skinflint editor! What’s got you buying dinner for indigent photographers?”

The man going by the name of Starkweather, for the moment, grinned. “To be perfectly honest, it wasn’t my idea. I came down to arrange to do a piece on Bill Haseltine, here, and he said he’d just run into you down in the Keys, and you’d seemed like the kind of man he could work with.” While I shook hands with Haseltine, Starkweather went on: “I don’t know how much you know about this guy, Matt, but he’s a great yachtsman and fisherman; and he just set a world’s record for tarpon in the new six-pound-line class. He’s got several other big-game fishing records on the books. Outdoors wants to do a story on him in action with a lot of color stuff… Well, let’s find our table and get some drinks in our hands. Bring yours along, Matt.” He ushered us toward the nearby dining room, still talking: “I don’t think a tarpon is quite the fish we want for the piece, too close to shore; and tuna don’t jump worth a damn. There aren’t many of either available right now, anyway. Sailfish and white marlin don’t run big enough as a rule, although either will do in a pinch; but a big blue marlin would be better if Bill can get one on and keep it there long enough for you to get the pictures. Let’s say that, for our purposes, Bill is now trying for the world’s record blue marlin on six-pound line. Of course, if it’s anywhere near normal size for these parts, it will probably break that silly little thread and get away, but we can make that the point of the story, showing that the problem of setting big-fish records with this ultra-light tackle is really a matter of finding one small enough to handle.” He was talking loudly enough that if anybody around didn’t know the subject of the conversation, he just wasn’t listening. Now Starkweather glanced at his watch and went on: “The trouble is, I’ve got a plane to catch; I can only stay a few minutes longer. Sorry, Matt, this just came up; dinner’s on me, anyway. I thought if I brought the two of you together you could work it out between you. You’ll need a good-looking fishing boat for as long as it takes, and maybe a chase boat for a day or two, but don’t break the bank, please…”

It was quite a performance. He left ten minutes later without having stopped talking once. For some moments of silence, Haseltine and I each drew a long breath of relief, simultaneously, and grinned at each other.

“Well, how did you make out at Walker’s?” Haseltine asked.

“Never mind that,” I said. “We can talk about fish later.”

“Sure.” Haseltine hesitated and spoke softly. “What do you know about the Bermuda Triangle, Helm?” he asked.

3

There are two kinds of rich Texans, the lanky cowboy type that made it with cattle, and the chunky truck-driver type that made it with oil. Scientifically speaking, the varieties are not distinct. There’s been a certain amount of interbreeding, and you will occasionally find a lean Gary Cooper specimen with a pasture full of oil wells, or a massive gent with the build of a wrestler and a pasture full of cows—the pasture, in each case, being approximately the size of Rhode Island.

The Haseltine stock, however, had apparently bred true ever since the first recorded beefy roughneck of that name brought in his first wildcat gusher and named it the Lulu-belle #1 or whatever his wife’s name—or current girl friend’s—happened to be. If I sound a little snide it’s because, although born elsewhere, I was brought up in New Mexico, a proud but impoverished state that tends to look askance at the antics of its gigantic, wealthy neighbor and the drawling, well-heeled citizens it exports in overpowering numbers. Call it jealousy if you like.

Big Bill Haseltine was at least six feet tall and weighed around two hundred and fifty pounds, not much of it fat. He had the smooth brown tan of a man who’s taken pains to get a smooth brown tan; an altogether different complexion from the leathery, squinty look of the man who’s actually been obliged to work outdoors and accept whatever the sun and wind dished out He had wide Indian cheekbones and thick, straight, coarse black Indian hair that retained the marks of the comb. His eyes were brown. They were friendly enough at the moment, but I didn’t trust them to stay that way if the man ever got drunk, or thought that he’d been double-crossed, or that somebody hadn’t treated him with the respect due the name of Haseltine.

I decided that if I ever had to take him, I’d better start when he wasn’t looking and use a club. He was too big and in too good condition for me to worry about trifles like fair and unfair.

“Sorry,” I said. “I was always lousy at geometry. The only triangle I can remember was called isosceles.”

“It’s sometimes known as the Bahama Triangle,” Haseltine said. “It’s also been called the Atlantic Twilight Zone, the Devil’s Triangle, the Triangle of Death, and the Sea of Missing Ships. It’s supposed to be haunted by sudden whirlpools large enough to suck down good-sized freighters and tankers, or immense sea monsters with hearty appetites for sailors and airplane pilots, or freak windstorms capable of totally disintegrating ships and planes, or very hostile unidentified flying objects equipped with real efficient vanishing rays. Take your choice.”

“Just what are the boundaries of this lethal area?” I asked.

“Well, you were right out in it, at Walker’s Cay,” said the sunburned man facing me. “It kind of depends who’s doing the survey, but generally speaking the line’s supposed to run from a point somewhere up the U.S. coast, out east to Bermuda, down southwest to a point somewhere in the neighborhood of Puerto Rico, say, and back up along Cuba and Florida to the starting point. Some writers have put the eastern corner as far off as the Azores, and the southern one way down near Tobago, but that’s stretching it a bit.”

“That’s a lot of water, regardless,” I said thoughtfully. “If I’ve got the picture right, the only real concentration of land included, except around the edges, is the Bahama Islands and the Bahama Banks—if you want to be generous and call all that shallow stuff land that I flew over in the plane this morning. What’s this about maelstroms and sea monsters?”

“Ships and planes keep disappearing out there,” Haseltine said. “Did you ever hear of Joshua Slocum?”

“The old gent who sailed around the world all by himself, long before Chichester and the others?” I said. “Sure, I’ve heard of him. Vaguely.”

“Slocum was a qualified sea captain, and as you say, he’d taken his little sloop clear around the world, the first man to make the voyage single-handed. You’d have to look hard to find a more experienced sailor. In 1909, Captain Slocum provisioned the Spray in Miami and headed for the West Indies, out in the Triangle. He was never seen again, and no trace of him or his boat was ever found.” Haseltine cleared his throat. “In 1918, the collier Cyclops left Barbados, bound for points north by way of the Triangle, and vanished. In 1945, a flight of five planes took off from the Naval Air Station right here in Fort Lauderdale and disappeared out there, all five of them. In spite of an intensive air and sea search, no identifiable debris was ever discovered. In 1958, the highly successful ocean-racing yawl Revonoc, a very seaworthy yacht with a topnotch skipper, went missing in the Triangle while sailing from Key West to Miami… Am I boring you, partner?” Apparently he could switch the Texas accent off and on. “Actually, I’m just picking and choosing. Adding up all the stories I’ve come across, just the ones that have been reasonably well authenticated, I figure that over a thousand folks in boats, ships, and planes, have simply dropped out of sight out there, in this century alone.”

He wasn’t boring me, but I was having a hard time trying to guess what a supposedly jinxed patch of ocean had to do with a gent named Pavel Minsk, due in Nassau the day after tomorrow.

I said, “And what have you lost out there, amigo?” When he looked up sharply, I grinned and said, “Pardon me, but you’re not exactly the type to do a lot of heavy research on this Hoodoo Sea without a personal interest.”

After a moment, Haseltine laughed. “I reckon I should have expected you to figure that out. The man in Washington said you had brains.”

I didn’t know whether or not I was supposed to react to this casual mention of Mac, if it was Mac he meant, so I didn’t. “Nice of him,” I said noncommittally.

“He also said you were a tough, cold-blooded character, a genius with firearms and edged weapons, a terror at unarmed combat, and a hell of a fine seaman to boot. Just the man I was looking for, in fact.”

It didn’t sound like Mac. At least he’d never laid it on that thick, talking to me. “I see,” I said.

“Look, Helm, I go first class,” said Haseltine. “I use only the best. Apparently, in this case, that’s you.”

I said, “Whether it’s true or not, it sounds nice. Keep talking.”

“Do you know what the average private investigator looks like? He’s a ratty little man who knows all about tailing people inconspicuously and planting bugs in motel rooms and snapping sexy pictures to go with the incriminating tapes, but show him a gun and he turns to jelly. When I heard—as you know, I’ve got some pretty good political connections—when I was told about the job you did over on the other side of Florida last spring, I knew you were the man I wanted. Well, I pulled some strings and was finally steered to our mutual friend in Washington. He sure doesn’t go in for publicity much, does he? He was damn hard and expensive to find. Does he always sit in front of that bright window? With that glare in my eyes, I couldn’t see enough of him to know him if I saw him on the street.”

“Maybe that’s the idea,” I said.

“Anyway, I put the proposition to him,” the big man went on calmly. “I showed him where it was to his advantage—a man in a job like that needs all the friends he can get—to lend me one of his best people for a week or two.”

He said it quite casually, as if he’d merely gone shopping for a good fishing rod, naturally in the classiest sporting goods emporium in town. It was, of course, fairly incredible. He might as well have said that he’d talked the late Mr. Hoover into renting him a G-man for a little private job he had in mind.

That the guy would even think it was startling enough, but a lot of money tends to affect a man’s mental processes, leading him to believe, more or less, that the rest of the world was invented just to serve him. The fantastic thing was, however, that Mac seemed to have gone along with the proposition, meekly agreeing to put a government agent, me, at this cocky Texan’s disposal.

I didn’t believe it for a minute, of course. That was the trouble. I’d never considered Mac, except for a bit of dry sarcasm now and then, as very strong in the humor department, but it was obvious that he was having a little joke at Big Bill Haseltine’s expense and expecting me to go along with the gag. Something was brewing in the Bahamas or adjacent areas. Maybe the tanned gent across the table was involved in some way; and letting him think he’d hired or borrowed me was a good way for me to keep an eye on him. On the other hand, it was perfectly possible that Haseltine’s problem was totally unrelated to ours; and that Mac had simply seen an easy way to spare the budget by getting a wealthy sucker to supply me with a plausible cover.

The fact that I was the guy who was going to have to duck the punches when Haseltine learned he’d been exploited was, of course, of no concern to Mac. I was supposed to be able to take care of myself. Well, the way he was setting this up, with both a cold-blooded Russian homicide specialist and a tough Texas millionaire soon to be after my hide, it looked as if I was going to have to live up to the fancy billing he’d given me, simply to survive.

I grinned. “Well, I never really bought that story about how grateful you were for all I’d done for you,” I said. “So I’m working for you for a week or two?”

“Let’s just say we’re working together, partner,” he said, surprisingly tactful. “As a matter of fact, you’ve been on the job for three days already, ever since you took off for Walker’s Cay. I wanted you to get the feel of the Islands; and also I wanted folks there to get the impression that you’re just an eager beginner at big-game fishing, panting for that first big marlin of your own, even while you’re snapping pictures for this hypothetical article about Haseltine the Great dragging in a thousand-pounder on six-pound line. Nuts! Have you ever used that stuff? Hell, man, it breaks of its own weight if you let the fish take out more than a hundred-odd yards of it. If you don’t have a good boat and a real gung-ho skipper who can keep you right on the fish’s tail, you’ve had it right now.” He grimaced. “How about cameras and film? Have you got enough to make it look good, wherever we wind up? If not, you’d better hit the stores in the morning and fix yourself up.”

I said, “I’ve got a little errand to run in Nassau, Mr. Haseltine. I guess I can pick up what I need there. I’ve got most of it. I used to really do it for a living, you know.”

“Who’s sending you to Nassau, the man in Washington?” Haseltine’s brown eyes narrowed and looked kind of muddy and ugly for a moment. “The understanding was that you’d be on my business full time. Maybe I’d better get on the phone and straighten him out…”

“Relax, Mr. Haseltine,” I said. “Whatever it is, it’s something related to your problem, just a hunch, he said, but I’d better check it out before I did anything else. I can’t tell you the details because it involves some people you’re not supposed to know about. After all, we’ve got to make some gestures toward security.”

“Yeah, sure.” He was still studying me suspiciously, as well he might, since I’d made up every word of what I’d said the instant before I’d said it, in the interest of millionaire diplomacy. Not that I knew that what I’d said was wrong, but I didn’t know it was right, either. Haseltine relaxed slowly. “Well, okay. If you want to play secret agent a bit, I guess it won’t hurt. We can get you from Nassau to wherever you need to go as soon as you’re ready, no sweat. And where the hell do you get this Mister-Haseltine routine, Matt?”

I grinned. “In this racket, we’re always respectful to the big brass, Bill. It makes them feel good, and it doesn’t make them a bit more bullet-proof if the time should ever come that we have to shoot them.”

He grinned back. We were pals—well, almost. “I wish I thought you were kidding,” he said. “I bet you would shoot me if I got in your way, you elongated bastard. Aren’t you going to ask what it is I want you to look for?”