4,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

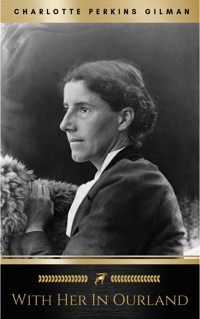

- Herausgeber: Charlotte Perkins Gilman

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

Moving the Mountain is novel written by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. It was published serially in Perkins Gilman's periodical The Forerunner and then in book form, both in 1911. The book was one element in the major wave of utopian and dystopian literature that marked the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.The novel was also the first volume in Gilman's utopian trilogy.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Moving the Mountain

by

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Preface

Chapter 1.

Chapter 2.

Chapter 3

Chapter 4.

Chapter 5.

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12.

Preface

ONE of the most distinctive features of the human mind is to forecast better things.

“We look before and after And pine for what is not.”

This natural tendency to hope, desire, foresee and then, if possible, obtain, has been largely diverted from human usefulness since our goal was placed after death, in Heaven. With all our hope in “Another World,” we have largely lost hope of this one.

Some minds, still keen in the perception of better human possibilities, have tried to write out their vision and give it to the world. From Plato’s ideal Republic to Wells’ Day of the Comet we have had many Utopias set before us, best known of which are that of Sir Thomas More and the great modern instance, “Looking Backward.”

All these have one or two distinctive features — an element of extreme remoteness, or the introduction of some mysterious out-side force. “Moving the Mountain” is a short distance Utopia, a baby Utopia, a little one that can grow. It involves no other change than a change of mind, the mere awakening of people, especially the women, to existing possibilities. It indicates what people might do, real people, now living, in thirty years — if they would.

One man, truly aroused and redirecting his energies, can change his whole life in thirty years.

So can the world.

Chapter 1.

ON a gray, cold, soggy Tibetan plateau stood glaring at one another two white people — a man and a woman.

With the first, a group of peasants; with the second, the guides and carriers of a well-equipped exploring party.

The man wore the dress of a peasant, but around him was a leather belt — old, worn, battered — but a recognizable belt of no Asiatic pattern, and showing a heavy buckle made in twisted initials.

The woman’s eye had caught the sunlight on this buckle before she saw that the heavily bearded face under the hood was white. She pressed forward to look at it.

“Where did you get that belt?” she cried, turning for the interpreter to urge her question.

The man had caught her voice, her words.

He threw back his hood and looked at her, with a strange blank look, as of one listening to something far away.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!