0,49 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

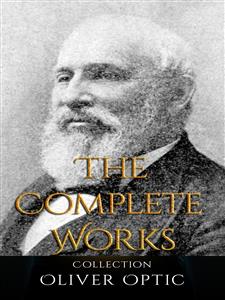

In "Our Standard-Bearer; Or, The Life of General Ulysses S. Grant," Oliver Optic presents a riveting biography that encapsulates the life and legacy of one of America's most pivotal military leaders and 18th President, Ulysses S. Grant. Written in a vivid narrative style that blends historical facts with engaging storytelling, the book captures the spirit of the Civil War era while providing a clear, accessible account of Grant's personal and professional struggles. Optic's work serves not only as a tribute to Grant's character and leadership but also as a critical commentary on the broader national identity being forged during and after the Civil War. Oliver Optic, the pen name of William Taylor Adams, was an influential American author known for his children's literature and adventure stories. His background as a teacher and lifelong interest in American history undoubtedly shaped his desire to write this biography. Optic's commitment to fostering patriotism and appreciation for American heroism is on full display in this work, as he seeks to inspire younger generations through Grant's narrative of perseverance and duty. This book is a must-read for anyone interested in American history, military strategy, or biographical literature. Optic'Äôs eloquent portrayal of Grant not only provides insight into a key figure in American history but also serves as a source of inspiration for resilience and leadership in the face of adversity. Readers will find themselves immersed in Grant's extraordinary journey, making it a timeless addition to any historical library.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Our Standard-Bearer; Or, The Life of General Uysses S. Grant

Table of Contents

PREFACE.

In this volume my friend Captain Galligasken has been permitted to tell his story very much in his own way. As I fully and heartily indorse his positions, fully and heartily share in his enthusiasm, my task has consisted of nothing more than merely writing the book; and I assure the reader that I have enjoyed quite as much as my friend the captain the pleasant contemplation of the brilliant deeds of the illustrious soldier. There is something positively inspiring in the following out of such a career as that of General Grant; and when I declare that the enthusiasm of Captain Galligasken is nothing more than just and reasonable, I do it after a careful examination of the grounds on which it is based; after a patient, but exceedingly agreeable, study of the character of the man whom we have jointly eulogized; and after instituting a critical comparison between the general and the mighty men of the present and the past. I have twice read all that I have written, and I find no occasion to add any qualifying words, and no reason to moderate the warm enthusiasm of the captain.

As the candidate for the presidency of the dominant party in the land, all of General Grant's sayings and doings will be subjected to the closest scrutiny by his political opponents. All that he has said and all that he has done will be remorselessly distorted by savage critics. Partisan prejudice and partisan hatred will pursue him into the privacies of life, as well as through every pathway and avenue of his public career; but Captain Galligasken joins me in the confident belief that no man has ever been held up to the gaze of the American people who could stand the test better; hardly one who could stand it as well. In his private life the general has been pure and guileless, while in his public history he has been animated by the most noble and exalted patriotism, ever willing to sacrifice all that he was and all that he had for the cause in which he embarked.

The study of the illustrious hero's motives and character has been exceedingly refreshing to me, as well as to my friend Captain Galligasken, as we analyzed together the influences which guided him in his eventful experience. We were unable to find any of those selfish and belittling springs of action which rob great deeds of more than half their glory. We could see in him a simplicity of character which amazed us; a strength of mind, a singleness of heart, which caused us to envy Sherman and Sheridan the possession of such a man's friendship. Unlike most eminent men, whose very greatness has induced them to shake off more or less of the traits of ordinary humanity, our illustrious soldier is a lovable man—an attitude in which we are seldom permitted to regard great men. He stands in violent contrast with the bombastic heroes of all times—modest, gentle-hearted, and always approachable. There is none of the frigid reserve in his manner which awes common people in the contemplation of those exalted by mighty deeds or a lofty position. Captain Galligasken says all this upon his honor as a soldier and an historian; and from my own personal stand-point I cordially indorse his opinion, which, in both instances, is derived from actual experience.

Captain Galligasken was somewhat afraid of the politicians, and not a little nervous at the possible manner those of the party to which he never had the honor to belong might regard his enthusiasm. I have taken the liberty to assure him that his enthusiasm is legitimate; that he has never manifested it except on suitable occasions; that the fact always specified in connection with the glowing eulogy amply justifies his praise. I was willing to go farther, and to insist that it was impossible for the politicians of his own or any other party to resist the conclusions, or withhold the homage, after the facts were admitted.

And this matter of facts, the unclothed skeleton of reliable history and biography, is a point on which my friend Captain Galligasken is especially sensitive. Our library of reference in the agreeable task we have jointly performed included all the works bearing on the subject now extant in the country. We have used them liberally and faithfully, and, animated by a desire to set forth "the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth" in regard to the illustrious soldier, the Captain feels entirely confident that he has produced a reliable history of all the important phases in his life. He has plentifully besprinkled his pages with anecdotes, some of which have never been related before, for they are the most telling illustrations of individual character.

We jointly acknowledge our indebtedness to General Adam Badeau's "Military History of Ulysses S. Grant," at once the most interesting and exhaustive work on the subject which has yet been issued, and which Captain Galligasken insists that every patriotic lover of the truth should read; to "Ohio in the War;" to "Grant and his Campaigns," by Professor Coppée, who had peculiar facilities for the performance of his task; to Howland's "Grant as a Soldier and a Statesman;" to Swinton's "Army of the Potomac;" to General Shanks's "Personal Recollections of Distinguished Generals;" and, in a less degree, to other volumes. Captain Galligasken is especially desirous of acknowledging his obligations to his friend Pollard, author of "The Lost Cause,"—though he thinks Grant is the chief author of the lost cause,—not only for the citations he has taken the liberty to make from the book, but also for some of the heartiest laughs he ever had in his life. We tender our personal thanks to those kind friends—whose names we are not even permitted to mention—for facts, suggestions, and anecdotes.

When our enterprising and discriminating publishers insisted upon just this Life of General Grant,—which I should not have been willing to undertake without the indispensable aid of my cheerful friend the captain,—we gladly accepted the agreeable task; but I noticed that Captain Galligasken appeared to be disturbed in his mind about something. I asked him what it was. He replied by asking me what possible excuse a humble individual like himself could offer for inflicting upon the patient, much-enduring community another Life of General Grant, who was even then more fortunate than a cat, for he had more than "nine lives." I bade him tell the reason, and he did.

"Because I can't help it," he replied; "because I desire to have the people of the United States see General Grant just as I see him. He has been nominated by the National Republican party as its candidate for the presidency, on a platform which every patriot, every Christian, heartily indorses, and which is the sum total of the general's political creed. I wish, if I can, to do something for his election; and I am fully persuaded that all the people would vote for him if they understood the man. I am no politician, never held an office, and never expect to hold one; but I believe in Grant above and beyond all party considerations. I respect, admire, and love the man. I glory in his past, and I am confident of his future. I honestly, sincerely, and heartily believe every word we have written. Nothing but the election of Grant can save the nation from the infamy of practical repudiation, from the distractions which have shaken the land since the close of the Rebellion, if not from another civil war and the ultimate dissolution of the Union. I hope the people will read our book, think well, and be as enthusiastic as I am."

It affords me very great pleasure, again and finally, to be able to indorse my friend Captain Galligasken. He is sincere; and before my readers condemn his enthusiasm, I beg to inquire how they can escape his conclusions. All we ask is a fair hearing, and we are confident that the people who sustained Grant through the war will enable him to finish in the presidential chair the glorious work he began on the battle-fields of the republic.

Oliver Optic.

Harrison Square, Mass., July 11, 1868.

Our Standard-Bearer;OR, THELife of General Ulysses S. Grant.

CHAPTER I.

Wherein Captain Galligasken modestly disparages himself, and sets forth with becoming Enthusiasm the Virtues of the illustrious Soldier whose Life he insists upon writing.

Who am I? It makes not the least difference who I am. If I shine at all in this veritable history,—which I honestly confess I have not the slightest desire to do,—it will be only in the reflected radiance of that great name which has become a household word in the home of every loyal citizen, north and south, of this mighty Republic; a name that will shine with transcendent lustre as his fame rings along down the grand procession of the ages, growing brighter and more glorious the farther it is removed from the petty jealousies of contemporaneous heroes, statesmen, and chroniclers.

What am I? It does not make the least difference what I am. I am to chronicle the deeds of that illustrious soldier, the providential man of the Great Rebellion, who beat down the strongholds of Treason by the force of his mighty will, and by a combination of moral and mental qualifications which have been united in no other man, either in the present or the past.

What was Washington? God bless him! A wise and prudent statesman, a devoted patriot, the savior of the new-born nationality.

What was Napoleon? The greatest soldier of the century which ended with the battle of Waterloo.

What was Andrew Jackson? The patriot statesman, who had a will of his own.

What were Cæsar, Wellington, Marlborough, Scott? All strong men, great soldiers, devoted patriots.

What is the Great Captain, the illustrious hero of the Modern Republic? He is all these men united into one. He has held within the grasp of his mighty thought larger armies than any other general who is worthy to be mentioned in comparison with him, controlling their movements, and harmonizing their action throughout a territory vastly larger than that comprised in the battle-grounds of Europe for a century.

Washington was great in spite of repeated defeats. Grant is great through a long line of brilliant successes. Napoleon won victories, and then clothed himself in the scarlet robes of an emperor, seated himself on a throne, and made his country's glory only the lever of his own glory. Grant won victories not less brilliant, and then modestly smoked his cigar on the grand level of the people, diffidently accepting any such honors as a grateful people thrust upon him.

As I yield the tribute of admiring homage to Washington that he put the Satan of sovereign power behind him when he was tempted with the glittering bait, I am amazed that Grant, the very idol of a million veteran soldiers, permitted his sword to rest in its scabbard while his recreant superior, by the accident of the assassin's bullet, dared to thwart the will of the people whose ballots had elevated him to power. I can almost worship him for his forbearance under the keenest insults to which the sensitive soul of a true soldier can be subjected, that he did not smite his cunning traducer, and did not even appeal to the people.

Who am I? If I am seen at all in this true narrative of a sublime life, I beg to be regarded as the most humble and least deserving of Columbia's chosen sons, but standing, for the moment, on a pedestal, and blushingly pointing to the historic canvas, whereon is delineated the triumphal career of the Great Man of the nineteenth century; the successful General, towering in lofty preëminence above every other man, who in the days of darkness struck a blow for the redemption of the nation; the fledged Statesman, who, without being a politician, apprehended and vitalized the chosen policy of the sovereign people. I am nothing; he is everything.

I am an enthusiast!

Is there nothing in The Man, sublimated by glorious deeds, elevated by a conquering will far above his fellows, almost deified by the highest development of godlike faculties,—is there nothing in The Man to quicken the lazy flow in the veins of the beholder? Can I, who marched from Belmont to Appomattox Court House, by the way of Donelson, Vicksburg, Chattanooga, Spottsylvania, Petersburg, and Five Forks, who have, since the collapse of the rebellion, gazed, in common with the Senators and Representatives in Congress, the Governors of the states, the President, and the heads of the departments of state, the sovereign people, with friends and with foes of the regenerated country,—can I, who have gazed with the most intense interest at the little two-story brick building in the nation's capital, where smoked and labored the genius of the war, to see what that one man would do, to hear what that one man would say,—can I gaze and listen without realizing the throb which heaves the mighty heart of the nation? I felt as they felt, that there was only one man in the land. It mattered little what senators and representatives enacted in the halls of Congress, if he did not indorse it. It mattered little what the Nation's Accident vetoed, if he but approved it. It was of little consequence what rebels north or rebels south planned and plotted, if only this one man frowned upon it. Reconstruction could flourish only in his smile. If a department commander ambitiously or stupidly belied his war record, and attempted to bolster up with this diplomacy the treason which he had put down with his sword, the howl of the loyal millions was changed into a shout of exultation, if the one man in the little two-story brick building in Washington only nodded his disapproval of the course of the recreant. That man has been the soul of the people's policy of reconstruction. Conscious that he was its friend, it mattered not who was its enemy; for foes could delay, but not defeat it.

Can I be unmoved while I look at The Man? When I behold a huge steamship, the giant of the deep, threading its way through night and storm over the pathless ocean, from continent to continent, herself a miracle to the eye, I wonder. When I see the electric telegraph, flashing a living thought from farthest east to farthest west, and even along its buried channel in the depths of the storm-tossed ocean, I wonder. Can I gaze unmoved upon the Man, the Fulton, the Morse, from whose busy brain, lighted up by an inspiration from the Infinite, which common men cannot even understand, came forth the grand conception of these miracles of science?

I am an enthusiast. I cannot gaze at the spectacle of a nation rent and shattered by the most stupendous treason that ever fouled historic annals, restored to peace and unity, without a thrill of emotion. I cannot follow our gallant armies in imagination now, as I did in reality then, in their triumphal march from the gloom of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville to the glorious light and sunshine of Vicksburg and Five Forks, from death at Bull Run, to life at Fort Donelson, without having my heart leap with grateful enthusiasm.

In the ghastly midnight of disaster, when the nation's pulse almost ceased to beat in dread and anxiety for the fearful issue, we had men—hundreds of thousands, millions of men, the bravest and truest soldiers that ever bore a musket. Thousands and tens of thousands of them sleep beneath the bloody sod of Antietam, in the miry swamps of the Chickahominy, and under the parching soil of the southern savannas, where they sank to their rest with the field unconquered above them. There they slumber, each of them a willing sacrifice, if his death brought the nation but one hair's breadth nearer to the final redemption, or could add one ray to the flood of light which the peace they prayed for would shed upon the land beloved.

There was no lack of men, and pure patriots prayed for a leader. They sighed for a Washington, a Napoleon, a Wellington, to guide their swelling masses of ardent warriors from the gloom of disaster to the brightness of victory. Chiefs, mighty in battle, pure in purpose, skilful in device and execution, reared their banners successively at the head of the valiant hosts, then drooped and fell, as the hot blast of jealousy swept over them, or they became entangled in the silken meshes of adulation. In none of these did the soldiers find their true leader, though they fought fiercely and fell in horrid slaughter under all of them.

It was only when the soul of the mustered hosts was fired by the sublime fact of a worthy leader, and their muscles nerved by the will of a mighty champion, that the thundering march of victory commenced, and the triumphal car of the conqueror swept like a whirlwind through the war-stricken South. Then treason trembled, tottered, few. Then the infatuated leaders of rebellion wailed in terror, and fled from the halter that dangled over their heads. Then the one man of the war towered like a giant above his fellows. Then he stood forth as the nation's savior, and a generous people placed the laurel on his brow.

I am an enthusiast as I review the history of my country from 1862 to the present time. I watched with McClellan in the oozy swamps of Virginia, when he feared to risk his popularity by striking an avenging stroke at the exposed foe, and I joined in singing the pæan of victory with Grant after Five Forks, when the final blow had been given to the rebellion. Therefore am I enthusiastic.

The people acknowledged the greatness of Grant's military genius, the tremendous power of his will, and the unflinching earnestness of his patriotism. Then, while salvos of artillery throughout the loyal land proclaimed the victory to the astonished nations, we hailed Grant as our standard-bearer.

If I am enthusiastic, so are the people, to their honor and glory be it said. I shall only ask to be their mouthpiece, assured that I cannot exceed their estimate of the hero. What he was in the storm of battle, he is in the calm pursuits of peace. What he was among the soldiers, he is among the citizens. As he possessed the unlimited confidence of the "boys in blue," so has he the unlimited confidence of the people. They are full of gratitude to him for the past, full of trust in him for the present, and full of hope in him for the future. In a tone more enthusiastic, and a voice more united than ever before since the days of Washington, the people have declared that Grant shall still be our standard-bearer, and I am more enthusiastic than ever.

Presumptuous as it may be in one so humble and little deserving as I am to intrude himself upon the public eye, I insist upon giving my views of the life of General Grant. I claim to know all about the distinguished subject of my story—which is no story at all, inasmuch as every word of it, so far as it relates to the general, is only the living truth, as I understand it. Even if my kind and courteous readers should deem me a myth, I shall only have won the obscurity I covet, and succeed in concentrating their attention upon the illustrious man whose immortal name I reverently utter, and whose undying deeds I seek to illustrate.

I wish to say in the beginning, that I hold it to be the sacred duty of the historian to tell the truth; so far as in him lies. For this reason I have taken the trouble, in this initial chapter of my work, to explain at some length the grounds of my individual enthusiasm in speaking and writing of the illustrious subject of this memoir. The fact, and my view of the fact, are two essentially different things. I shall state facts as I find them; and whatever view my indulgent reader may entertain in regard to me and my views, I assure him, on the honor of an historian, that all my statements are true, and worthy of the utmost credit.

Others may not be willing to agree with me in all respects in my estimate of particular events or incidents in the life of my illustrious subject, though I am persuaded there can be no essential difference in our view of the sum-total of the general—that he must stand unchallenged as the greatest man and the greatest soldier of the nineteenth century, if not of all time. A proper regard for the sacred truth of history compels me to make this declaration, which I do without the fear of a denial.

I have been very much pained to observe that my friend, Mr. Pollard, author of "The Lost Cause," has arrived at an estimate of the merit of our distinguished general, which is, in some respects, different from my own. Perhaps my valued contemporary was unable to derive the necessary inspiration from his subject to enable him to do full justice to the shining abilities of some of the heroes who, unfortunately for The Lost Cause, were on the other side of the unpleasant controversy. Doubtless Mr. Pollard meant well; but it is painful to find that he has, in some cases, exhibited symptoms of prejudice, especially towards General Grant, who does not seem to be a favorite general with him. I notice also on his pages a degree of partiality towards General Lee which greatly astonishes me. After a careful examination of Mr. Pollard's voluminous work, I am surprised and grieved to find that he actually regards Lee, in the matter of soldier-like qualities and in generalship, as the superior of Grant!

I confess my surprise at his singular position; but in view of the fact that he is writing the history of "The Lost Cause"—lost, the world acknowledges, through the active agency of General Grant,—I am disposed to palliate, though not to excuse, my friend's departures from the sacred line of historic truth. Mr. Lee is doubtless a very amiable and kind-hearted gentleman, though we must protest against his inhumanity to the Belle Island prisoners; but I object to any comparison of him, as a general, with Grant. When Mr. Pollard shall have time to go over the ground again, he will see his blunders, and, being an honest man, he will have the hardihood to correct them. Then "The Lost Cause" will be to him, as to the rest of mankind, a monument of the folly and wickedness of those who engaged in it, a solemn warning to traitors and conspirators, and the best panegyric of the true hero of the war which a rebel pen could indite.

Though, as I said before, it makes no difference who or what I am, it will be no more than courtesy for me to satisfy the reasonable curiosity of my readers on these points, before I enter upon the pleasant task before me. Though one of my ancestors, some ten generations back, was born in the parish of Blarney, in the County of Cork, Ireland, I was not born there. Sir Bernard Galligasken—whose name, shorn of its aristocratic handle, I have the honor to bear—was one of the earliest known, at the present time, of our stock, and emigrated to Scotland, where he married one of the Grants of Aberdeenshire. My more immediate progenitor came over in the Mayflower, and landed on Plymouth Rock, for which, on this account, as well as because I love the principles of those stalwart men of the olden time, I have ever had the most profound veneration. Early in the present century my parents removed from Eastern Massachusetts to the Great West.

I was born at Point Pleasant, Ohio, April 27, 1822. By a singular coincidence (on my side) was born in the same town, and on the same day, Hiram Ulysses Grant.

CHAPTER II.

Wherein Captain Galligasken delineates the early History of the illustrious Soldier, and deduces therefrom the Presages of Future Greatness.

I respectfully subscribe myself a cosmopolitan, not in the sense that I am a citizen of the world—God forbid! for I am too proud of my title as an American citizen to share my nationality with any other realm under the sun. I am cosmopolitan in the "everywhere" significance of the term; and it has been a cause of sincere regret to me that I could only be in one place at one time; but I ought to be content, since I always happened to be in sight or hearing of the illustrious subject of my feeble admiration.

Point Pleasant is a village on the Ohio, twenty-five miles above Cincinnati, celebrated for nothing in particular, except being the birthplace of General Grant, which, however, is glory enough for any town; and passengers up and down the beautiful river, for generations to come, will gaze with wondering interest at its spires, because there first drew the breath of life the immortal man who has been and still is Our Standard-Bearer.

Many people have a fanatical veneration for blood as such. I confess I yield no allegiance to this sentiment, for I expect to be what I make myself, rather than what I am made by my distinguished ancestor, Sir Bernard Galligasken. But those who attach any weight to pedigree may be reasonably gratified in the solid character of the progenitors of General Grant. He came from the Grants of Aberdeenshire, in Scotland, whose heraldic motto was, "Stand fast, stand firm, stand sure!" which, by an astonishing prescience of the seers of the clan, seems to have been invented expressly to describe the moral and mental attributes of the illustrious soldier of our day.

Matthew Grant was a passenger in the Mary and John, and settled in Dorchester, Massachusetts, in 1630. The American citizen, whose pride tempts him to look beyond the Pilgrim Fathers for glorious ancestors, ought to have been born in England, where pride of birth bears its legitimate fruit. Grant came in a direct line from one of these worthies; but I never heard him congratulate himself even on this fortunate and happy origin. Noah Grant, a descendant of the stout Puritan, emigrated to Connecticut, and was a captain in the Old French War. He was killed in battle, in 1756, having attained the rank of captain. His son, also taking the patriarchal name, was belligerent enough to have been killed in battle, for he was a soldier in the revolutionary war from Lexington—where he served as a lieutenant—to Yorktown, the last engagement of that seven years' strife. This faithful soldier was the general's grandfather. He had a son named for Mr. Chief Justice Jesse Root, of Connecticut, who was the father of Our Standard-Bearer.

Jesse Root Grant was born in Pennsylvania, but when he was ten years of age his parents removed to the Western Reserve of Ohio. He was apprenticed to a tanner at Maysville, Kentucky, when he was sixteen, and set up in business for himself at Ravenna, Ohio, when he was of age; but severe illness compelled him to relinquish it for a time. In 1820 he settled at Point Pleasant, and married Miss Hannah Simpson. Here, in a little one-story house, still in existence, was born the subject of our story.

The house in which Peter the Great lived at Sardam while he worked at ship-building is still preserved, enclosed within another, tableted with inscriptions, and protected from the ravages of time for the inspection of future ages. I wonder that some ardent patriot has not already done a similar service to the little structure in which was born a greater than Czar Peter, and one whose memory will be cherished when the autocrat of the Russias is forgotten.

The house is a mere shanty, which was comfortable enough in its day, with an extension in the rear, and with the chimney on the outside of one end. It was a good enough house even for so great a man to be born in, and compares very favorably with that in which Lincoln, his co-laborer in the war, first drew the breath of life. It has become historic now, and the people will always regard it with glowing interest.

Grant's mother was a very pretty, but not pretentious, girl; a very worthy, but not austere, matron. She was a member of the Methodist church, with high views of Christian duty, especially in regard to her children, whom she carefully trained and earnestly watched over in their early years. Her influence as a noble Christian woman has had, and is still to have, through her illustrious son, more weight and broader expansion than she ever dreamed of in the days of her poverty and toil.

A year after the birth of the first born, Jesse Grant, then a poor man, though he afterwards accumulated a handsome property, removed from Point Pleasant to Georgetown, Ohio, where he carried on his business as a tanner; and as he tanned with nothing but oak bark, and did his work in a superior manner, his reputation was excellent. I am hard on leather myself, but my first pair of shoes was made of leather from the tannery of J.R. Grant, and they wore like iron. It has been observed that this leather, made up into thick boots, was more effectual than any other when applied by the indignant owner to the purpose sometimes necessary, though always disagreeable, of kicking an unmannerly and ill-behaved ruffian out of doors. Though I have not had occasion to test Mr. Grant's leather in this direction, I am a firm believer in its virtue.

I cannot say that, as a baby, Ulysses had any fore-shadowings of the brilliant destiny in store for him. It is quite possible that his fond mother regarded him as a remarkable child, if the neighbors in Georgetown did not. Certainly, in this instance, she was nearer right than loving mothers usually are, and is entitled to much credit for the justness of her view on this interesting subject. I am confident that the infant Hercules displayed some of the energy of which has distinguished his manhood—that he declined to be washed, and held on to dangerous play-things, with greater tenacity than children of tender years usually do. Still, the sacredness of historic truth does not permit me to assume that he displayed any of the traits of a great general, except the embryo of his mighty will, until he had attained his second year, when the first decided penchant for the roar of artillery manifested itself on a small scale.

My friend Mr. Pollard alludes to the incident in his valuable work on The Lost Cause, though, I am pained to observe, in a tone of disparagement quite unworthy of him, as a "Yankee affectation." As he seems to have no scruples in telling strange stories about Stonewall Jackson, Jeb. Stuart, and other Southern worthies, I am compelled to attribute this incredulity and ridicule to a foolish prejudice. Though I happened to be present when the event occurred,—a cosmopolitan then, as now,—I was in the arms of my maternal parent, and being only two years old at the time, I am unable to vouch for its truth on my own personal recollection; but the father of General Grant has confirmed it.

"Let me try the effect of a pistol report on the baby," said a young man to the anxious parent in the street, on the fourth of July, where great numbers of people were gathered.

"The child has never seen a pistol or a gun in his life," replied Mr. Grant; "but you may try it."

The hand of the baby was placed on the trigger, and pressed there till the lock sprang, and the pistol went off with a loud report. The future commander-in-chief hardly moved or twitched a muscle.

"Fick it again! fick it again!" cried the child, pushing away the weapon, and desiring to have the experiment repeated.

"That boy will make a general; he neither winked nor dodged," added the inevitable bystander, a cosmopolitan like myself, who is ever at hand on momentous occasions.

To me, the trait of character exhibited by the child is not so much the type of a taste for the rattle of musketry and the odor of gunpowder as of a higher manifestation of soldier-like qualities. After weary days and long nights of the thunder of cannon at Donelson, when ordinary generals would have been disgusted and disheartened by continued failure, Grant persevered, not knowing that he had been beaten, and in tones full of grand significance, though in speech more mature, he repeats his order,—

"Fick it again! fick it again!"

When canal, and squadron, and repeated assaults had failed to reduce Vicksburg, and friend and foe believed that the place was invulnerable, Grant seemed to shout,—

"Fick it again! fick it again!"

When, after the terrible onslaught of the Union army at the Wilderness, no advantage seemed to have been gained, and the time came when Grant's predecessors had fled to recruit in a three months' respite, the heroic leader only said, in substance,—

"Fick it again! fick it again!"

At Spottsylvania he hurled his army again at the rebel host, and then fought battle after battle, never completely succeeding, but never turning his eye or his thought from the object to be gained: he still maintained his baby philosophy, and still issued the order of the day, which was, practically,—

"Fick it again! fick it again!"

That celebrated telegram, sent to Secretary Stanton, which thrilled the hearts of the waiting people as they listened for the tidings of battle, and which was a most significant exponent of the man's character and purpose, "I shall fight it out on this line, if it takes all summer," was only another rendering of his childish exclamation,—

"Fick it again! fick it again!"

Fort Donelson, Vicksburg, Richmond, the Rebellion itself, were fully and completely "ficked," in the end, by the carrying out of his policy. It is an excellent rule, when a plan does not work in one way, to "fick" it again.

Grant's father was too poor at this time to send him to school steadily, for the boy was an industrious fellow, and had a degree of skill and tact in the management of work that rendered him a very useful assistant. He went to school three months in winter till he was eleven, when even this meagre privilege was denied him, and his subsequent means of education were very limited. But his opportunities were fully improved, and he heartily devoted himself to the cultivation of his mind. He was the original discoverer of the fact that there is no such word as "can't" in the dictionary; and it appears never to have been added to his vocabulary. Grant's dictionary was a capital one for practical service; and if some of our generals had used this excellent edition, their own fame and the country's glory would have been thereby promoted.

It affords me very great pleasure to be able to testify, in the most decided manner, that Grant was a patriot in his boyhood, as well as in the later years of his life. As an American youth, he had a just and proper reverence for the name of Washington, which is the symbol of patriotism to our countrymen. Grant's cousin from Canada came to live with his uncle for a time in Georgetown, and went to school with the juvenile hero. This lad, though born under the shadow of the Star-spangled Banner, had imbibed some pestilent notions from the Canadians, and had the audacity to speak ill of the immortal Washington. This was not the only time that Americans from Canada have assailed their native land, nor was this the only time that Ulysses had the honor of fighting the battle directly or indirectly against them. On the present occasion, in spite of the oft-repeated admonition of his pious mother to forgive his enemies and not to fight, he pitched into the renegade and thrashed him soundly, as he deserved to be thrashed. I never spoke ill of Washington, but I should esteem it a great honor to have been thrashed by Ulysses S. Grant in such a cause; and doubtless his cousin, if still living, and not a Canadian, is proud of his whipping.

Grant appears not to have been a brilliant horse-trader, at least not after the tactics of jockeys in general, though in this, as in all other purposes, he carried his point. At the age of twelve his father sent him to buy a certain horse—and it ought to be remarked that his worthy sire seems to have had as much confidence in him at that time as the sovereign people of the present day manifest in him. He was instructed to offer fifty dollars for the animal; then fifty-five if the first offer failed, with the limit at sixty. Ralston, the owner of the horse, wished to know how much the youthful purchaser was authorized by his father to give for the animal. Ulysses, with a degree of candor which would have confounded an ordinary jockey, explained his instructions in full, and of course the owner asked the maximum sum for him.

Though the youth had "shown his hand," he was not the easy victim he was supposed to be. He positively refused to give more than fifty dollars for the horse, after he had seen and examined him. He had made up his mind, and the horse was purchased for that sum. I think Grant bought out the Rebellion in about the same way; for while he was ready to pay "fifty-five," or even "sixty," for the prize of a nation's peace and unity, the rebels came down at the "fifty."

Grant was a good boy, in the reasonable sense of the term, though he did not die young. I never heard that he made any extravagant pretensions to piety himself, or that any one ever made any for him, though he attended church himself regularly, and had a profound respect for religious worship. He was a sober, quiet little fellow, indulged in no long speeches then any more than now. He was a youth of eminent gravity, rather an old head on young shoulders, and I am only surprised that neither his parents nor his instructors discovered in him the germ of greatness. As the child is father to the man, all the records of his early years concur in showing that he exhibited the same traits of character then as now.

The phrenologist who examined Ulysses' "bumps," and declared that "it would not be strange" if he became the President of the United States, exhibited more intelligence than others within the ring; but I am provoked with him that he did not state the case stronger; for if there is anything at all in phrenology, the gentleman ought to have been confident of this result. Any man may become President, as the stupendous accident of the present generation has shown, but every man is not fit for the place. It is vastly better to be qualified to fill the high position, than it is even to fill it. As Grant was the providential man of the war, so shall he be the providential man of the peace that follows it in the highest office within the gift of the people. No accident can cheat him out of his destiny, which he willingly accepts, more for the glory of the nation than of the individual.

CHAPTER III.

Wherein Captain Galligasken "talks Horse," and illustrates the Subject with some Anecdotes from the Life of the illustrious Soldier.

The horse is a noble animal, and it is by no means remarkable that a bond of sympathy has been established between great men and good horses. I have noticed that distinguished generals are always mounted on splendid steeds—a fact of which painters and sculptors have availed themselves in their delineations, on canvas or in marble, of the heroes and mighty men of history. Bucephalus, the war-charger of Alexander the Great, seems to be almost a part of the Macedonian conqueror; Washington, in the various equestrian attitudes in which he is presented to the admiring gaze of the people by the artist, appears to gain power and dignity from the noble steed he rides; and scores of lesser heroes, dismounted and detached from the horse, would, so far as the eye is concerned, slip down from the pedestal of grandeur to the level of common men. Though it is sometimes unfortunate that the limner's idea of the man is better than of the horse, it will be universally acknowledged that the gallant steed adds dignity and grace to the hero.

Although it has not yet been the good fortune of the American people to behold any worthy equestrian delineation of our illustrious soldier, either on canvas or in marble, yet the popular ideal would represent him as a sort of Centaur—half horse and half Grant. While I am by no means willing to acknowledge that every man who "talks horse" is necessarily a great man, it is undeniable that great military geniuses have figured attractively and appropriately in intimate association with this intelligent and noble animal. The inspired writers used the horse to add grandeur and sublimity to their imagery, and St. John's vision of Death on the Pale Horse thrills the soul by the boldness of the equestrian attitude in which it places the grim destroyer.

The centaur which the American people idolize is not an unworthy combination, and neither the man nor the horse loses by the association. From the time the embryo hero could go alone—if there ever was a time when he could not go alone—Grant fancied the horse; Grant loved the horse; Grant conquered the horse.

Bucephalus was offered for sale to Philip by a Thessalian horse-jockey. He was a glorious horse, but neither groom nor courtier could handle him. So fierce was his untamed will, that the king ordered the jockey to take him away; but Alexander, grieved at the thought of losing so fine a steed, remonstrated with his father, who promised to buy him if his son would ride him. Alexander did ride him, and the horse became his war-charger in all his campaigns.

In his early and intimate association with the horse, young Grant exhibited the force of his immense will, even more effectively than his Macedonian prototype.

When children of seven "talk horse," they do so at a respectful distance from the object of their admiration, with a lively consciousness that the animal has teeth and heels. At this age Grant demonstrated his enterprise by operating with a three-year-old colt. I do not profess to be a great man, as I have before had occasion to remark, or to possess any of the elements of greatness; but I do like a horse, while I am free to say I should as soon think of teaching an African lion to dance a hornpipe as to meddle with a three-year-old colt. However good-natured the creature may be, he has an innate independence of character, which makes him restive, and even vicious, under restraint. I never break colts.

Georgetown, where we lived in those early days, was about seven miles from the Ohio. One day Grant's father went to Ripley, a small town on the river, and remained there all day. The juvenile centaur had an idea on that occasion, which for a seven-year-old, may be regarded as an emphatically brilliant one. On the place was a three-year-old colt, which had been used under the saddle, but never attached to a vehicle of any kind. It required some confidence on the part of the youth to think of harnessing this unbroken animal; yet he not only conceived the idea, but actually carried it out. He put the collar on the three-year-old for the first time, attached him to a sled, and hauled wood with him all day. At eight years of age he was the regular teamster on his father's place. At ten he used to drive a span of horses to Cincinnati, forty miles distant, and return with a freight of passengers, but with no adult to direct or control him.

The pony trick at the circuses which travel over the country is not a new thing; and when a call was made for a boy to ride the fractious little beast, trained to throw the daring youngster who had the hardihood to mount him, for the amusement of the gaping crowd, Ulysses used to be a regular volunteer. I never offered my services, because I had a proper respect for the unity of my corporeal frame. Grant, bent on overcoming some new obstacle, was always on hand, and always as sure to succeed as he was to undertake any difficult feat.

On one occasion a peculiarly vicious little rascal of a pony was attached to one of these shows which exhibited in our town. Grant, as usual, was the only youngster who had the pluck to venture upon the difficult feat of riding him. He mounted the little villain, and away he darted with the speed of the lightning, resorting to all manner of mean tricks to dismount his bold rider. Round the ring he whirled, flying rather than running, and increasing his efforts to unhorse the determined youth, who sat as steadily as though he had been the veritable, instead of the figurative, Centaur. Grant carried too many guns for that pony.

A large monkey, included in the programme of the performance, was next let loose, to assist in dismounting the rider. The little demon sprang up behind the volunteer equestrian, and away dashed the pony at redoubled speed. The intelligent but excited audience shouted with laughter, but the youth was unmoved either by the pony, the monkey, or the storming applause of the crowd. He could neither be bullied nor coaxed from his position. Then the gentlemanly master of the ring caused the monkey to mount the shoulders of the intrepid youngster, and hold on at his hair. Away went the pony once more, and a new effort was made to throw the unconquered young horseman. The crowd shouted and roared with renewed energy as the scene became more ludicrous and more exciting; but Grant's nerves were still steady, and his face still wore its resolute, unmoved expression. As usual with those who attempt to throw him, somebody besides Grant had to give in. He was too much for pony, monkey, and ring-master combined.

I am well aware that I am enthusiastic; I have made full confession of my enthusiasm, and I am not ashamed of it; but I cannot help regarding this exciting incident as a type of events in the subsequent career of that bold rider. When he mounted the pony to ride into Fort Donelson, he was not to be shaken from his seat; he went in. That same pony—after all sorts of vicious attempts to pitch him into the Mississippi, or heave him over into the swamps—carried him safely into Vicksburg, after almost as many turns around the ring and the ring-master—one Pemberton on this occasion—as in the circus at Georgetown.

On a still larger scale, with one Jefferson Davis as ring-master, he was induced to mount the emblematic pony of the army of the Potomac, an exceedingly well-trained steed, which, however, had succeeded in throwing all his previous riders. Little Mac went round the ring very handsomely, and so far as the pony was concerned, proved himself to be master of the situation; but the monkey, which, in this case, appeared to be his personal reputation, too dear to be risked upon any issue short of absolute certainty, was too much for him, and he was unhorsed. His immediate successors held on well for a brief period; but the monkey of jealousy, insubordination, or vanity, very soon gave them a wretched tumble, even before the crowd had ceased to applaud.

Grant had ridden too many horses to be overwhelmed by this pony. The ring-master kept his eye on the daring rider, expecting soon to see him pitched off by the pony, with the assistance of the monkey. He started from the Wilderness one day, and every device was used to unseat him; but he did not move a muscle when the ring-master cracked his whip, or even when the monkey perched upon his shoulders. He fought it out on that line, and brought up at Appomattox Court House. The ring-master gave up, and closed the performance.