Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Phoemixx Classics Ebooks

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

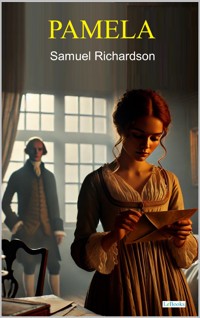

Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded Samuel Richardson - For a fascinating glimpse into eighteenth-century morals and values, take a look at Samuel Richardson's Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded. A blockbuster of a bestseller in its day, Pamela recounts the tribulations of a poor housekeeper who is forced constantly to fend off the prurient advances of her employer. Her reward? Pamela is offeredand acceptsher lustful master's hand in marriage and is thrust into upper-class society.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 2190

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PUBLISHER NOTES:

Take our Free

Quick Quiz and Find Out Which

Best Side Hustle is ✓Best for You.

✓ VISIT OUR WEBSITE:

→LYFREEDOM.COM ← ← CLICK HERE ←

VOLUME 1

Publishers' Note

Samuel Richardson, the first, in order of time, of the great English novelists, was born in 1689 and died at London in 1761. He was a printer by trade, and rose to be master of the Stationers' Company. That he also became a novelist was due to his skill as a letter-writer, which brought him, in his fiftieth year, a commission to write a volume of model “familiar letters” as an aid to persons too illiterate to compose their own. The notion of connecting these letters by a story which had interested him suggested the plot of “Pamela” and determined its epistolary form—a form which was retained in his later works.

This novel (published 1740) created an epoch in the history of English fiction, and, with its successors, exerted a wide influence upon Continental literature. It is appropriately included in a series which is designed to form a group of studies of English life by the masters of English fiction. For it marked the transition from the novel of adventure to the novel of character—from the narration of entertaining events to the study of men and of manners, of motives and of sentiments. In it the romantic interest of the story (which is of the slightest) is subordinated to the moral interest in the conduct of its characters in the various situations in which they are placed. Upon this aspect of the “drama of human life” Richardson cast a most observant, if not always a penetrating glance. His works are an almost microscopically detailed picture of English domestic life in the early part of the eighteenth century.

Letter 1

Dear Fatherand Mother,

I have great trouble, and some comfort, to acquaint you with. The trouble is, that my good lady died of the illness I mentioned to you, and left us all much grieved for the loss of her; for she was a dear good lady, and kind to all us her servants. Much I feared, that as I was taken by her ladyship to wait upon her person, I should be quite destitute again, and forced to return to you and my poor mother, who have enough to do to maintain yourselves; and, as my lady's goodness had put me to write and cast accounts, and made me a little expert at my needle, and otherwise qualified above my degree, it was not every family that could have found a place that your poor Pamela was fit for: but God, whose graciousness to us we have so often experienced at a pinch, put it into my good lady's heart, on her death-bed, just an hour before she expired, to recommend to my young master all her servants, one by one; and when it came to my turn to be recommended, (for I was sobbing and crying at her pillow) she could only say, My dear son!—and so broke off a little; and then recovering—Remember my poor Pamela—And these were some of her last words! O how my eyes run—Don't wonder to see the paper so blotted.

Well, but God's will must be done!—And so comes the comfort, that I shall not be obliged to return back to be a clog upon my dear parents! For my master said, I will take care of you all, my good maidens; and for you, Pamela, (and took me by the hand; yes, he took my hand before them all,) for my dear mother's sake, I will be a friend to you, and you shall take care of my linen. God bless him! and pray with me, my dear father and mother, for a blessing upon him, for he has given mourning and a year's wages to all my lady's servants; and I having no wages as yet, my lady having said she should do for me as I deserved, ordered the housekeeper to give me mourning with the rest; and gave me with his own hand four golden guineas, and some silver, which were in my old lady's pocket when she died; and said, if I was a good girl, and faithful and diligent, he would be a friend to me, for his mother's sake. And so I send you these four guineas for your comfort; for Providence will not let me want: And so you may pay some old debt with part, and keep the other part to comfort you both. If I get more, I am sure it is my duty, and it shall be my care, to love and cherish you both; for you have loved and cherished me, when I could do nothing for myself. I send them by John, our footman, who goes your way: but he does not know what he carries; because I seal them up in one of the little pill-boxes, which my lady had, wrapt close in paper, that they mayn't chink; and be sure don't open it before him.

I know, dear father and mother, I must give you both grief and pleasure; and so I will only say, Pray for your Pamela; who will ever be

Your most dutiful daughter.

I have been scared out of my senses; for just now, as I was folding up this letter in my late lady's dressing-room, in comes my young master! Good sirs! how was I frightened! I went to hide the letter in my bosom; and he, seeing me tremble, said, smiling, To whom have you been writing, Pamela?—I said, in my confusion, Pray your honour forgive me!—Only to my father and mother. He said, Well then, let me see how you are come on in your writing! O how ashamed I was!—He took it, without saying more, and read it quite through, and then gave it me again;—and I said, Pray your honour forgive me!—Yet I know not for what: for he was always dutiful to his parents; and why should he be angry that I was so to mine? And indeed he was not angry; for he took me by the hand, and said, You are a good girl, Pamela, to be kind to your aged father and mother. I am not angry with you for writing such innocent matters as these: though you ought to be wary what tales you send out of a family.—Be faithful and diligent; and do as you should do, and I like you the better for this. And then he said, Why, Pamela, you write a very pretty hand, and spell tolerably too. I see my good mother's care in your learning has not been thrown away upon you. She used to say you loved reading; you may look into any of her books, to improve yourself, so you take care of them. To be sure I did nothing but courtesy and cry, and was all in confusion, at his goodness. Indeed he is the best of gentlemen, I think! But I am making another long letter: So will only add to it, that I shall ever be Your dutiful daughter, PamelaAndrews.

Letter 2

[In answer to the preceding.]

Dear Pamela,

Your letter was indeed a great trouble, and some comfort, to me and your poor mother. We are troubled, to be sure, for your good lady's death, who took such care of you, and gave you learning, and, for three or four years past, has always been giving you clothes and linen, and every thing that a gentlewoman need not be ashamed to appear in. But our chief trouble is, and indeed a very great one, for fear you should be brought to anything dishonest or wicked, by being set so above yourself. Every body talks how you have come on, and what a genteel girl you are; and some say you are very pretty; and, indeed, six months since, when I saw you last, I should have thought so myself, if you was not our child. But what avails all this, if you are to be ruined and undone!—Indeed, my dear Pamela, we begin to be in great fear for you; for what signify all the riches in the world, with a bad conscience, and to be dishonest! We are, 'tis true, very poor, and find it hard enough to live; though once, as you know, it was better with us. But we would sooner live upon the water, and, if possible, the clay of the ditches I contentedly dig, than live better at the price of our child's ruin.

I hope the good 'squire has no design: but when he has given you so much money, and speaks so kindly to you, and praises your coming on; and, oh, that fatal word! that he would be kind to you, if you would do as you should do, almost kills us with fears.

I have spoken to good old widow Mumford about it, who, you know, has formerly lived in good families; and she puts us in some comfort; for she says it is not unusual, when a lady dies, to give what she has about her person to her waiting-maid, and to such as sit up with her in her illness. But, then, why should he smile so kindly upon you? Why should he take such a poor girl as you by the hand, as your letter says he has done twice? Why should he stoop to read your letter to us; and commend your writing and spelling? And why should he give you leave to read his mother's books?—Indeed, indeed, my dearest child, our hearts ache for you; and then you seem so full of joy at his goodness, so taken with his kind expressions, (which, truly, are very great favours, if he means well) that we fear—yes, my dear child, we fear—you should be too grateful,—and reward him with that jewel, your virtue, which no riches, nor favour, nor any thing in this life, can make up to you.

I, too, have written a long letter, but will say one thing more; and that is, that, in the midst of our poverty and misfortunes, we have trusted in God's goodness, and been honest, and doubt not to be happy hereafter, if we continue to be good, though our lot is hard here; but the loss of our dear child's virtue would be a grief that we could not bear, and would bring our grey hairs to the grave at once.

If, then, you love us, if you wish for God's blessing, and your own future happiness, we both charge you to stand upon your guard: and, if you find the least attempt made upon your virtue, be sure you leave every thing behind you, and come away to us; for we had rather see you all covered with rags, and even follow you to the churchyard, than have it said, a child of ours preferred any worldly conveniences to her virtue.

We accept kindly your dutiful present; but, till we are out of pain, cannot make use of it, for fear we should partake of the price of our poor daughter's shame: so have laid it up in a rag among the thatch, over the window, for a while, lest we should be robbed. With our blessings, and our hearty prayers for you, we remain,

Your careful, but loving Father and Mother,

John and Elizabeth Andrews.

Letter 3

Dear Father,

I must needs say, your letter has filled me with trouble, for it has made my heart, which was overflowing with gratitude for my master's goodness, suspicious and fearful: and yet I hope I shall never find him to act unworthy of his character; for what could he get by ruining such a poor young creature as me? But that which gives me most trouble is, that you seem to mistrust the honesty of your child. No, my dear father and mother, be assured, that, by God's grace, I never will do any thing that shall bring your grey hairs with sorrow to the grave. I will die a thousand deaths, rather than be dishonest any way. Of that be assured, and set your hearts at rest; for although I have lived above myself for some time past, yet I can be content with rags and poverty, and bread and water, and will embrace them, rather than forfeit my good name, let who will be the tempter. And of this pray rest satisfied, and think better of Your dutiful daughter till death.

My master continues to be very affable to me. As yet I see no cause to fear any thing. Mrs. Jervis, the housekeeper, too, is very civil to me, and I have the love of every body. Sure they can't all have designs against me, because they are civil! I hope I shall always behave so as to be respected by every one; and that nobody would do me more hurt than I am sure I would do them. Our John so often goes your way, that I will always get him to call, that you may hear from me, either by writing, (for it brings my hand in,) or by word of mouth.

Letter 4

Dear Mother,

For the last was to my father, in answer to his letter; and so I will now write to you; though I have nothing to say, but what will make me look more like a vain hussy, than any thing else: However, I hope I shan't be so proud as to forget myself. Yet there is a secret pleasure one has to hear one's self praised. You must know, then, that my Lady Davers, who, I need not tell you, is my master's sister, has been a month at our house, and has taken great notice of me, and given me good advice to keep myself to myself. She told me I was a pretty wench, and that every body gave me a very good character, and loved me; and bid me take care to keep the fellows at a distance; and said, that I might do, and be more valued for it, even by themselves.

But what pleased me much was, what I am going to tell you; for at table, as Mrs. Jervis says, my master and her ladyship talking of me, she told him she thought me the prettiest wench she ever saw in her life; and that I was too pretty to live in a bachelor's house; since no lady he might marry would care to continue me with her. He said, I was vastly improved, and had a good share of prudence, and sense above my years; and that it would be pity, that what was my merit should be my misfortune.—No, says my good lady, Pamela shall come and live with me, I think. He said, with all his heart; he should be glad to have me so well provided for. Well, said she, I'll consult my lord about it. She asked how old I was; and Mrs. Jervis said, I was fifteen last February. O! says she, if the wench (for so she calls all us maiden servants) takes care of herself, she'll improve yet more and more, as well in her person as mind.

Now, my dear father and mother, though this may look too vain to be repeated by me; yet are you not rejoiced, as well as I, to see my master so willing to part with me?—This shews that he has nothing bad in his heart. But John is just going away; and so I have only to say, that I am, and will always be,

Your honest as well as dutiful daughter.

Pray make use of the money. You may now do it safely.

Letter 5

My Dear Father and Mother,

John being to go your way, I am willing to write, because he is so willing to carry any thing for me. He says it does him good at his heart to see you both, and to hear you talk. He says you are both so sensible, and so honest, that he always learns something from you to the purpose. It is a thousand pities, he says, that such worthy hearts should not have better luck in the world! and wonders, that you, my father, who are so well able to teach, and write so good a hand, succeeded no better in the school you attempted to set up; but was forced to go to such hard labour. But this is more pride to me, that I am come of such honest parents, than if I had been born a lady.

I hear nothing yet of going to Lady Davers; and I am very easy at present here: for Mrs. Jervis uses me as if I were her own daughter, and is a very good woman, and makes my master's interest her own. She is always giving me good counsel, and I love her next to you two, I think, best of any body. She keeps so good rule and order, she is mightily respected by us all; and takes delight to hear me read to her; and all she loves to hear read, is good books, which we read whenever we are alone; so that I think I am at home with you. She heard one of our men, Harry, who is no better than he should be, speak freely to me; I think he called me his pretty Pamela, and took hold of me, as if he would have kissed me; for which, you may be sure, I was very angry: and she took him to task, and was as angry at him as could be; and told me she was very well pleased to see my prudence and modesty, and that I kept all the fellows at a distance. And indeed I am sure I am not proud, and carry it civilly to every body; but yet, methinks, I cannot bear to be looked upon by these men-servants, for they seem as if they would look one through; and, as I generally breakfast, dine, and sup, with Mrs. Jervis, (so good she is to me,) I am very easy that I have so little to say to them. Not but they are civil to me in the main, for Mrs. Jervis's sake, who they see loves me; and they stand in awe of her, knowing her to be a gentlewoman born, though she has had misfortunes. I am going on again with a long letter; for I love writing, and shall tire you. But, when I began, I only intended to say, that I am quite fearless of any danger now: and, indeed, cannot but wonder at myself, (though your caution to me was your watchful love,) that I should be so foolish as to be so uneasy as I have been: for I am sure my master would not demean himself, so as to think upon such a poor girl as I, for my harm. For such a thing would ruin his credit, as well as mine, you know: who, to be sure, may expect one of the best ladies in the land. So no more at present, but that I am

Your ever dutiful daughter.

Letter 6

Dear Father and Mother,

My master has been very kind since my last; for he has given me a suit of my late lady's clothes, and half a dozen of her shifts, and six fine handkerchiefs, and three of her cambric aprons, and four holland ones. The clothes are fine silk, and too rich and too good for me, to be sure. I wish it was no affront to him to make money of them, and send it to you: it would do me more good.

You will be full of fears, I warrant now, of some design upon me, till I tell you, that he was with Mrs. Jervis when he gave them me; and he gave her a mort of good things, at the same time, and bid her wear them in remembrance of her good friend, my lady, his mother. And when he gave me these fine things, he said, These, Pamela, are for you; have them made fit for you, when your mourning is laid by, and wear them for your good mistress's sake. Mrs. Jervis gives you a very good word; and I would have you continue to behave as prudently as you have done hitherto, and every body will be your friend.

I was so surprised at his goodness, that I could not tell what to say. I courtesied to him, and to Mrs. Jervis for her good word; and said, I wished I might be deserving of his favour, and her kindness: and nothing should be wanting in me, to the best of my knowledge.

O how amiable a thing is doing good!—It is all I envy great folks for.

I always thought my young master a fine gentleman, as every body says he is: but he gave these good things to us both with such a graciousness, as I thought he looked like an angel.

Mrs. Jervis says, he asked her, If I kept the men at a distance? for, he said, I was very pretty; and to be drawn in to have any of them, might be my ruin, and make me poor and miserable betimes. She never is wanting to give me a good word, and took occasion to launch out in my praise, she says. But I hope she has said no more than I shall try to deserve, though I mayn't at present. I am sure I will always love her, next to you and my dear mother. So I rest

Your ever dutiful daughter.

Letter 7

Dear Father,

Since my last, my master gave me more fine things. He called me up to my late lady's closet, and, pulling out her drawers, he gave me two suits of fine Flanders laced headclothes, three pair of fine silk shoes, two hardly the worse, and just fit for me, (for my lady had a very little foot,) and the other with wrought silver buckles in them; and several ribands and top-knots of all colours; four pair of white fine cotton stockings, and three pair of fine silk ones; and two pair of rich stays. I was quite astonished, and unable to speak for a while; but yet I was inwardly ashamed to take the stockings; for Mrs. Jervis was not there: If she had, it would have been nothing. I believe I received them very awkwardly; for he smiled at my awkwardness, and said, Don't blush, Pamela: Dost think I don't know pretty maids should wear shoes and stockings?

I was so confounded at these words, you might have beat me down with a feather. For you must think, there was no answer to be made to this: So, like a fool, I was ready to cry; and went away courtesying and blushing, I am sure, up to the ears; for, though there was no harm in what he said, yet I did not know how to take it. But I went and told all to Mrs. Jervis, who said, God put it into his heart to be good to me; and I must double my diligence. It looked to her, she said, as if he would fit me in dress for a waiting-maid's place on Lady Davers's own person.

But still your kind fatherly cautions came into my head, and made all these gifts nothing near to me what they would have been. But yet, I hope, there is no reason; for what good could it do to him to harm such a simple maiden as me? Besides, to be sure no lady would look upon him, if he should so disgrace himself. So I will make myself easy; and, indeed, I should never have been otherwise, if you had not put it into my head; for my good, I know very well. But, may be, without these uneasinesses to mingle with these benefits, I might be too much puffed up: So I will conclude, all that happens is for our good; and God bless you, my dear father and mother; and I know you constantly pray for a blessing upon me; who am, and shall always be,

Your dutiful daughter.

Letter 8

Dear Pamela,

I cannot but renew my cautions on your master's kindness, and his free expression to you about the stockings. Yet there may not be, and I hope there is not, any thing in it. But when I reflect, that there possibly may, and that if there should, no less depends upon it than my child's everlasting happiness in this world and the next; it is enough to make one fearful for you. Arm yourself, my dear child, for the worst; and resolve to lose your life sooner than your virtue. What though the doubts I filled you with, lessen the pleasure you would have had in your master's kindness; yet what signify the delights that arise from a few paltry fine clothes, in comparison with a good conscience?

These are, indeed, very great favours that he heaps upon you, but so much the more to be suspected; and when you say he looked so amiably, and like an angel, how afraid I am, that they should make too great an impression upon you! For, though you are blessed with sense and prudence above your years, yet I tremble to think, what a sad hazard a poor maiden of little more than fifteen years of age stands against the temptations of this world, and a designing young gentleman, if he should prove so, who has so much power to oblige, and has a kind of authority to command, as your master.

I charge you, my dear child, on both our blessings, poor as we are, to be on your guard; there can be no harm in that. And since Mrs. Jervis is so good a gentlewoman, and so kind to you, I am the easier a great deal, and so is your mother; and we hope you will hide nothing from her, and take her counsel in every thing. So, with our blessings, and assured prayers for you, more than for ourselves, we remain,

Your loving Father and Mother.

Be sure don't let people's telling you, you are pretty, puff you up; for you did not make yourself, and so can have no praise due to you for it. It is virtue and goodness only, that make the true beauty. Remember that, Pamela.

Letter 9

Dear Fatherand Mother,

I am sorry to write you word, that the hopes I had of going to wait on Lady Davers, are quite over. My lady would have had me; but my master, as I heard by the by, would not consent to it. He said her nephew might be taken with me, and I might draw him in, or be drawn in by him; and he thought, as his mother loved me, and committed me to his care, he ought to continue me with him; and Mrs. Jervis would be a mother to me. Mrs. Jervis tells me the lady shook her head, and said, Ah! brother! and that was all. And as you have made me fearful by your cautions, my heart at times misgives me. But I say nothing yet of your caution, or my own uneasiness, to Mrs. Jervis; not that I mistrust her, but for fear she should think me presumptuous, and vain and conceited, to have any fears about the matter, from the great distance between such a gentleman, and so poor a girl. But yet Mrs. Jervis seemed to build something upon Lady Davers's shaking her head, and saying, Ah! brother! and no more. God, I hope, will give me his grace: and so I will not, if I can help it, make myself too uneasy; for I hope there is no occasion. But every little matter that happens, I will acquaint you with, that you may continue to me your good advice, and pray for

Your sad-hearted Pamela.

Letter 10

Dear Mother,

You and my good father may wonder you have not had a letter from me in so many weeks; but a sad, sad scene, has been the occasion of it. For to be sure, now it is too plain, that all your cautions were well grounded. O my dear mother! I am miserable, truly miserable!—But yet, don't be frightened, I am honest!—God, of his goodness, keep me so!

O this angel of a master! this fine gentleman! this gracious benefactor to your poor Pamela! who was to take care of me at the prayer of his good dying mother; who was so apprehensive for me, lest I should be drawn in by Lord Davers's nephew, that he would not let me go to Lady Davers's: This very gentleman (yes, I must call him gentleman, though he has fallen from the merit of that title) has degraded himself to offer freedoms to his poor servant! He has now shewed himself in his true colours; and, to me, nothing appear so black, and so frightful.

I have not been idle; but had writ from time to time, how he, by sly mean degrees, exposed his wicked views; but somebody stole my letter, and I know not what has become of it. It was a very long one. I fear, he that was mean enough to do bad things, in one respect, did not stick at this. But be it as it will, all the use he can make of it will be, that he may be ashamed of his part; I not of mine: for he will see I was resolved to be virtuous, and gloried in the honesty of my poor parents.

I will tell you all, the next opportunity; for I am watched very narrowly; and he says to Mrs. Jervis, This girl is always scribbling; I think she may be better employed. And yet I work all hours with my needle, upon his linen, and the fine linen of the family; and am, besides, about flowering him a waistcoat.—But, oh! my heart's broke almost; for what am I likely to have for my reward, but shame and disgrace, or else ill words, and hard treatment! I'll tell you all soon, and hope I shall find my long letter.

Your most afflicted daughter.

May-be, I he and him too much: but it is his own fault if I do. For why did he lose all his dignity with me?

Letter 11

Dear Mother,

Well, I can't find my letter, and so I'll try to recollect it all, and be as brief as I can. All went well enough in the main for some time after my letter but one. At last, I saw some reason to suspect; for he would look upon me, whenever he saw me, in such a manner, as shewed not well; and one day he came to me, as I was in the summer-house in the little garden, at work with my needle, and Mrs. Jervis was just gone from me; and I would have gone out, but he said, No don't go, Pamela; I have something to say to you; and you always fly me when I come near you, as if you were afraid of me.

I was much out of countenance, you may well think; but said, at last, It does not become your good servant to stay in your presence, sir, without your business required it; and I hope I shall always know my place.

Well, says he, my business does require it sometimes; and I have a mind you should stay to hear what I have to say to you.

I stood still confounded, and began to tremble, and the more when he took me by the hand; for now no soul was near us.

My sister Davers, said he, (and seemed, I thought, to be as much at a loss for words as I,) would have had you live with her; but she would not do for you what I am resolved to do, if you continue faithful and obliging. What say'st thou, my girl? said he, with some eagerness; had'st thou not rather stay with me, than go to my sister Davers? He looked so, as filled me with affrightment; I don't know how; wildly, I thought.

I said, when I could speak, Your honour will forgive me; but as you have no lady for me to wait upon, and my good lady has been now dead this twelvemonth, I had rather, if it would not displease you, wait upon Lady Davers, because—

I was proceeding, and he said, a little hastily—Because you are a little fool, and know not what's good for yourself. I tell you I will make a gentlewoman of you, if you be obliging, and don't stand in your own light; and so saying, he put his arm about me, and kissed me!

Now, you will say, all his wickedness appeared plainly. I struggled and trembled, and was so benumbed with terror, that I sunk down, not in a fit, and yet not myself; and I found myself in his arms, quite void of strength; and he kissed me two or three times, with frightful eagerness.—At last I burst from him, and was getting out of the summer-house; but he held me back, and shut the door.

I would have given my life for a farthing. And he said, I'll do you no harm, Pamela; don't be afraid of me. I said, I won't stay. You won't, hussy! said he: Do you know whom you speak to? I lost all fear, and all respect, and said, Yes, I do, sir, too well!—Well may I forget that I am your servant, when you forget what belongs to a master.

I sobbed and cried most sadly. What a foolish hussy you are! said he: Have I done you any harm? Yes, sir, said I, the greatest harm in the world: You have taught me to forget myself and what belongs to me, and have lessened the distance that fortune has made between us, by demeaning yourself, to be so free to a poor servant. Yet, sir, I will be bold to say, I am honest, though poor: and if you was a prince, I would not be otherwise.

He was angry, and said, Who would have you otherwise, you foolish slut! Cease your blubbering. I own I have demeaned myself; but it was only to try you. If you can keep this matter secret, you'll give me the better opinion of your prudence; and here's something, said he, putting some gold in my hand, to make you amends for the fright I put you in. Go, take a walk in the garden, and don't go in till your blubbering is over: and I charge you say nothing of what is past, and all shall be well, and I'll forgive you.

I won't take the money, indeed, sir, said I, poor as I am I won't take it. For, to say truth, I thought it looked like taking earnest, and so I put it upon the bench; and as he seemed vexed and confused at what he had done, I took the opportunity to open the door, and went out of the summer-house.

He called to me, and said, Be secret; I charge you, Pamela; and don't go in yet, as I told you.

O how poor and mean must those actions be, and how little must they make the best of gentlemen look, when they offer such things as are unworthy of themselves, and put it into the power of their inferiors to be greater than they!

I took a turn or two in the garden, but in sight of the house, for fear of the worst; and breathed upon my hand to dry my eyes, because I would not be too disobedient. My next shall tell you more.

Pray for me, my dear father and mother: and don't be angry I have not yet run away from this house, so late my comfort and delight, but now my terror and anguish. I am forced to break off hastily.

Your dutiful and honest daughter.

Letter 12

Dear Mother,

Well, I will now proceed with my sad story. And so, after I had dried my eyes, I went in, and began to ruminate with myself what I had best to do. Sometimes I thought I would leave the house and go to the next town, and wait an opportunity to get to you; but then I was at a loss to resolve whether to take away the things he had given me or no, and how to take them away: Sometimes I thought to leave them behind me, and only go with the clothes on my back, but then I had two miles and a half, and a byway, to the town; and being pretty well dressed, I might come to some harm, almost as bad as what I would run away from; and then may-be, thought I, it will be reported, I have stolen something, and so was forced to run away; and to carry a bad name back with me to my dear parents, would be a sad thing indeed!—O how I wished for my grey russet again, and my poor honest dress, with which you fitted me out, (and hard enough too it was for you to do it!) for going to this place, when I was not twelve years old, in my good lady's days! Sometimes I thought of telling Mrs. Jervis, and taking her advice, and only feared his command to be secret; for, thought I, he may be ashamed of his actions, and never attempt the like again: And as poor Mrs. Jervis depended upon him, through misfortunes, that had attended her, I thought it would be a sad thing to bring his displeasure upon her for my sake.

In this quandary, now considering, now crying, and not knowing what to do, I passed the time in my chamber till evening; when desiring to be excused going to supper, Mrs. Jervis came up to me, and said, Why must I sup without you, Pamela? Come, I see you are troubled at something; tell me what is the matter.

I begged I might be permitted to be with her on nights; for I was afraid of spirits, and they would not hurt such a good person as she. That was a silly excuse, she said; for why was not you afraid of spirits before?—(Indeed I did not think of that.) But you shall be my bed-fellow with all my heart, added she, let your reason be what it will; only come down to supper. I begged to be excused; for, said I, I have been crying so, that it will be taken notice of by my fellow-servants; and I will hide nothing from you, Mrs. Jervis, when we are alone.

She was so good to indulge me; but made haste to come up to bed; and told the servants, that I should be with her, because she could not rest well, and would get me to read her to sleep; for she knew I loved reading, she said.

When we were alone, I told her all that had passed; for I thought, though he had bid me not, yet if he should come to know I had told, it would be no worse; for to keep a secret of such a nature, would be, as I apprehended, to deprive myself of the good advice which I never wanted more; and might encourage him to think I did not resent it as I ought, and would keep worse secrets, and so make him do worse by me. Was I right, my dear mother?

Mrs. Jervis could not help mingling tears with my tears; for I cried all the time I was telling her the story, and begged her to advise me what to do; and I shewed her my dear father's two letters, and she praised the honesty and editing of them, and said pleasing things to me of you both. But she begged I would not think of leaving my service; for, said she, in all likelihood, you behaved so virtuously, that he will be ashamed of what he has done, and never offer the like to you again: though, my dear Pamela, said she, I fear more for your prettiness than for anything else; because the best man in the land might love you: so she was pleased to say. She wished it was in her power to live independent; then she would take a little private house, and I should live with her like her daughter.

And so, as you ordered me to take her advice, I resolved to tarry to see how things went, except he was to turn me away; although, in your first letter, you ordered me to come away the moment I had any reason to be apprehensive. So, dear father and mother, it is not disobedience, I hope, that I stay; for I could not expect a blessing, or the good fruits of your prayers for me, if I was disobedient.

All the next day I was very sad, and began my long letter. He saw me writing, and said (as I mentioned) to Mrs. Jervis, That girl is always scribbling; methinks she might find something else to do, or to that purpose. And when I had finished my letter, I put it under the toilet in my late lady's dressing-room, whither nobody comes but myself and Mrs. Jervis, besides my master; but when I came up again to seal it, to my great concern, it was gone; and Mrs. Jervis knew nothing of it; and nobody knew of my master's having been near the place in the time; so I have been sadly troubled about it: But Mrs. Jervis, as well as I, thinks he has it, some how or other; and he appears cross and angry, and seems to shun me, as much as he said I did him. It had better be so than worse!

But he has ordered Mrs. Jervis to bid me not pass so much time in writing; which is a poor matter for such a gentleman as he to take notice of, as I am not idle other ways, if he did not resent what he thought I wrote upon. And this has no very good look.

But I am a good deal easier since I lie with Mrs. Jervis; though, after all, the fears I live in on one side, and his frowning and displeasure at what I do on the other, make me more miserable than enough.

O that I had never left my little bed in the loft, to be thus exposed to temptations on one hand, or disgusts on the other! How happy was I awhile ago! How contrary now!—Pity and pray for

Your afflicted

Pamela.

Letter 13

My Dearest Child,

Our hearts bleed for your distress, and the temptations you are exposed to. You have our hourly prayers; and we would have you flee this evil great house and man, if you find he renews his attempts. You ought to have done it at first, had you not had Mrs. Jervis to advise with. We can find no fault in your conduct hitherto: But it makes our hearts ache for fear of the worst. O my child! temptations are sore things,—but yet, without them, we know not ourselves, nor what we are able to do.

Your danger is very great; for you have riches, youth, and a fine gentleman, as the world reckons him, to withstand; but how great will be your honour to withstand them! And when we consider your past conduct, and your virtuous education, and that you have been bred to be more ashamed of dishonesty than poverty, we trust in God, that He will enable you to overcome. Yet, as we can't see but your life must be a burthen to you, through the great apprehensions always upon you; and that it may be presumptuous to trust too much to our own strength; and that you are but very young; and the devil may put it into his heart to use some stratagem, of which great men are full, to decoy you: I think you had better come home to share our poverty with safety, than live with so much discontent in a plenty, that itself may be dangerous. God direct you for the best! While you have Mrs. Jervis for an adviser and bed-fellow, (and, O my dear child! that was prudently done of you,) we are easier than we should be; and so committing you to the divine protection, remain

Your truly loving, but careful,

Father and Mother.

Letter 14

Dear Fatherand Mother,

Mrs. Jervis and I have lived very comfortably together for this fortnight past; for my master was all that time at his Lincolnshire estate, and at his sister's, the Lady Davers. But he came home yesterday. He had some talk with Mrs. Jervis soon after, and mostly about me. He said to her, it seems, Well, Mrs. Jervis, I know Pamela has your good word; but do you think her of any use in the family? She told me she was surprised at the question, but said, That I was one of the most virtuous and industrious young creatures that ever she knew. Why that word virtuous, said he, I pray you? Was there any reason to suppose her otherwise? Or has any body taken it into his head to try her?—I wonder, sir, says she, you ask such a question! Who dare offer any thing to her in such an orderly and well-governed house as yours, and under a master of so good a character for virtue and honour? Your servant, Mrs. Jervis, says he, for your good opinion: but pray, if any body did, do you think Pamela would let you know it? Why, sir, said she, she is a poor innocent young creature, and I believe has so much confidence in me, that she would take my advice as soon as she would her mother's. Innocent! again, and virtuous, I warrant! Well, Mrs. Jervis, you abound with your epithets; but I take her to be an artful young baggage; and had I a young handsome butler or steward, she'd soon make her market of one of them, if she thought it worth while to snap at him for a husband. Alack-a-day, sir, said she, it is early days with Pamela; and she does not yet think of a husband, I dare say: and your steward and butler are both men in years, and think nothing of the matter. No, said he, if they were younger, they'd have more wit than to think of such a girl; I'll tell you my mind of her, Mrs. Jervis: I don't think this same favourite of yours so very artless a girl as you imagine. I am not to dispute with your honour, said Mrs. Jervis; but I dare say, if the men will let her alone, she'll never trouble herself about them. Why, Mrs. Jervis, said he, are there any men that will not let her alone, that you know of? No, indeed, sir, said she; she keeps herself so much to herself, and yet behaves so prudently, that they all esteem her, and shew her as great a respect as if she was a gentlewoman born.

Ay, says he, that's her art, that I was speaking of: but, let me tell you, the girl has vanity and conceit, and pride too, or I am mistaken; and, perhaps, I could give you an instance of it. Sir, said she, you can see farther than such a poor silly woman as I am; but I never saw any thing but innocence in her—And virtue too, I'll warrant ye! said he. But suppose I could give you an instance, where she has talked a little too freely of the kindnesses that have been shewn her from a certain quarter; and has had the vanity to impute a few kind words, uttered in mere compassion to her youth and circumstances, into a design upon her, and even dared to make free with names that she ought never to mention but with reverence and gratitude; what would you say to that?—Say, sir! said she, I cannot tell what to say. But I hope Pamela incapable of such ingratitude.

Well, no more of this silly girl, says he; you may only advise her, as you are her friend, not to give herself too much licence upon the favours she meets with; and if she stays here, that she will not write the affairs of my family purely for an exercise to her pen, and her invention. I tell you she is a subtle, artful gipsy, and time will shew it you.

Was ever the like heard, my dear father and mother? It is plain he did not expect to meet with such a repulse, and mistrusts that I have told Mrs. Jervis, and has my long letter too, that I intended for you; and so is vexed to the heart. But I can't help it. I had better be thought artful and subtle, than be so, in his sense; and, as light as he makes of the words virtue and innocence in me, he would have made a less angry construction, had I less deserved that he should do so; for then, may be, my crime should have been my virtue with him naughty gentleman as he is!

I will soon write again; but must now end with saying, that I am, and shall always be, Your honest daughter.

Letter 15

Dear Mother,

I broke off abruptly my last letter; for I feared he was coming; and so it happened. I put the letter in my bosom, and took up my work, which lay by me; but I had so little of the artful, as he called it, that I looked as confused as if I had been doing some great harm.

Sit still, Pamela, said he, mind your work, for all me.—You don't tell me I am welcome home, after my journey to Lincolnshire. It would be hard, sir, said I, if you was not always welcome to your honour's own house.

I would have gone; but he said, Don't run away, I tell you. I have a word or two to say to you. Good sirs, how my heart went pit-a-pat! When I was a little kind to you, said he, in the summer-house, and you carried yourself so foolishly upon it, as if I had intended to do you great harm, did I not tell you you should take no notice of what passed to any creature? and yet you have made a common talk of the matter, not considering either my reputation, or your own.—I made a common talk of it, sir! said I: I have nobody to talk to, hardly.

He interrupted me, and said, Hardly! you little equivocator! what do you mean by hardly? Let me ask you, have not you told Mrs. Jervis for one? Pray your honour, said I, all in agitation, let me go down; for it is not for me to hold an argument with your honour. Equivocator, again! said he, and took my hand, what do you talk of an argument? Is it holding an argument with me to answer a plain question? Answer me what I asked. O, good sir, said I, let me beg you will not urge me farther, for fear I forget myself again, and be saucy.

Answer me then, I bid you, says he, Have you not told Mrs. Jervis? It will be saucy in you if you don't answer me directly to what I ask. Sir, said I, and fain would have pulled my hand away, perhaps I should be for answering you by another question, and that would not become me. What is it you would say? replies he; speak out.

Then, sir, said I, why should your honour be so angry I should tell Mrs. Jervis, or any body else, what passed, if you intended no harm?

Well said, pretty innocent and artless! as Mrs. Jervis calls you, said he; and is it thus you taunt and retort upon me, insolent as you are! But still I will be answered directly to my question. Why then, sir, said I, I will not tell a lie for the world: I did tell Mrs. Jervis; for my heart was almost broken; but I opened not my mouth to any other. Very well, boldface, said he, and equivocator again! You did not open your mouth to any other; but did not you write to some other? Why, now, and please your honour, said I, (for I was quite courageous just then,) you could not have asked me this question, if you had not taken from me my letter to my father and mother, in which I own I had broken my mind freely to them, and asked their advice, and poured forth my griefs!

And so I am to be exposed, am I, said he, in my own house, and out of my house, to the whole world, by such a sauce-box as you? No, good sir, said I, and I hope your honour won't be angry with me; it is not I that expose you, if I say nothing but the truth. So, taunting again! Assurance as you are! said he: I will not be thus talked to!

Pray, sir, said I, of whom can a poor girl take advice, if it must not be of her father and mother, and such a good woman as Mrs. Jervis, who, for her sex-sake, should give it me when asked? Insolence! said he, and stamped with his foot, am I to be questioned thus by such a one as you? I fell down on my knees, and said, For Heaven's sake, your honour, pity a poor creature, that knows nothing of her duty, but how to cherish her virtue and good name: I have nothing else to trust to: and, though poor and friendless here, yet I have always been taught to value honesty above my life. Here's ado with your honesty, said he, foolish girl! Is it not one part of honesty to be dutiful and grateful to your master, do you think? Indeed, sir, said I, it is impossible I should be ungrateful to your honour, or disobedient, or deserve the names of bold-face or insolent, which you call me, but when your commands are contrary to that first duty which shall ever be the principle of my life!

He seemed to be moved, and rose up, and walked into the great chamber two or three turns, leaving me on my knees; and I threw my apron over my face, and laid my head on a chair, and cried as if my heart would break, having no power to stir.

At last he came in again, but, alas! with mischief in his heart! and raising me up, he said, Rise, Pamela, rise; you are your own enemy. Your perverse folly will be your ruin: I tell you this, that I am very much displeased with the freedoms you have taken with my name to my housekeeper, as also to your father and mother; and you may as well have real cause to take these freedoms with me, as to make my name suffer for imaginary ones. And saying so, he offered to take me on his knee, with some force. O how I was terrified! I said, like as I had read in a book a night or two before, Angels and saints, and all the host of heaven, defend me! And may I never survive one moment that fatal one in which I shall forfeit my innocence! Pretty fool! said he, how will you forfeit your innocence, if you are obliged to yield to a force you cannot withstand? Be easy, said he; for let the worst happen that can, you will have the merit, and I the blame; and it will be a good subject for letters to your father and mother, and a tale into the bargain for Mrs. Jervis.

He by force kissed my neck and lips; and said, Whoever blamed Lucretia? All the shame lay on the ravisher only and I am content to take all the blame upon me, as I have already borne too great a share for what I have not deserved.

May I, said I, Lucretia like, justify myself with my death, if I am used barbarously! O my good girl! said he, tauntingly, you are well read, I see; and we shall make out between us, before we have done, a pretty story in romance, I warrant ye.

He then put his hand in my bosom, and indignation gave me double strength, and I got loose from him by a sudden spring, and ran out of the room! and the next chamber being open, I made shift to get into it, and threw to the door, and it locked after me; but he followed me so close, he got hold of my gown, and tore a piece off, which hung without the door; for the key was on the inside.

I just remember I got into the room; for I knew nothing further of the matter till afterwards; for I fell into a fit with my terror, and there I lay, till he, as I suppose, looking through the key-hole, spyed me upon the floor, stretched out at length, on my face; and then he called Mrs. Jervis to me, who, by his assistance, bursting open the door, he went away, seeing me coming to myself; and bid her say nothing of the matter, if she was wise.

Poor Mrs. Jervis thought it was worse, and cried over me like as if she was my mother; and I was two hours before I came to myself; and just as I got a little up on my feet, he coming in, I fainted away again with the terror; and so he withdrew: but he staid in the next room to let nobody come near us, that his foul proceedings might not be known.

Mrs. Jervis gave me her smelling-bottle, and had cut my laces, and set me in a great chair, and he called her to him: How is the girl? said he: I never saw such a fool in my life. I did nothing at all to her. Mrs. Jervis could not speak for crying. So he said, She has told you, it seems, that I was kind to her in the summer-house, though I'll assure you, I was quite innocent then as well as now; and I desire you to keep this matter to yourself, and let me not be named in it.

O, sir, said she, for your honour's sake, and for Christ's sake!—But he would not hear her, and said—For your own sake, I tell you, Mrs. Jervis, say not a word more. I have done her no harm. And I won't have her stay in my house; prating, perverse fool, as she is! But since she is so apt to fall into fits, or at least pretend to do so, prepare her to see me to-morrow after dinner, in my mother's closet, and do you be with her, and you shall hear what passes between us.

And so he went out in a pet, and ordered his chariot and four to be got ready, and went a visiting somewhere.