Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jazzybee Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

This is the annotated edition including a rare and extensive biographical essay on the author, as well as an introductory to the book written by George Parsons Lathrop. The series of passages from the "American Note-Books" covers the space of eighteen years, almost to a day; the extracts running from June 15, 1835, to June 9, 1853; and in a detached way it represents the main part of Hawthorne's career throughout the period of his rise from obscurity to fame, purely as a growth of American soil and conditions, before he had ever set foot in Europe.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 657

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Passages From The American Note-Books

Nathaniel Hawthorne

Contents:

Nathaniel Hawthorne – A Biographical Primer

Passages From The American Note-Books

Introductory Note To The American Note-Books.

1835

1836

1837

1838

1839

1840

1839

1840

1841

1842

1843

1844

1850

1851

1852

1853

Passages From The American Note-Books, N. Hawthorne

Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck

86450 Altenmünster, Loschberg 9

Germany

ISBN:9783849640996

www.jazzybee-verlag.de

www.facebook.com/jazzybeeverlag

Nathaniel Hawthorne – A Biographical Primer

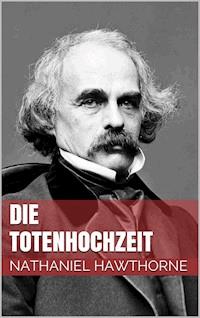

By Edward Everett Hale

American novelist: b. Salem, Mass., 4 July 1804; d. Plymouth, N. H., 19 May 1864. The founder of the family in America was William Hathorne (as the name was then spelled), a typical Puritan and a public man of importance. John, his son, was a judge, one of those presiding over the witchcraft trials. Of Joseph in the next generation little is said, but Daniel, next in decent, followed the sea and commanded a privateer in the Revolution, while his son Nathaniel, father of the romancer, was also a sea Captain. This pure New England descent gave a personal character to Hawthorne's presentations of New England life; when he writes of the strictness of the early Puritans, of the forests haunted by Indians, of the magnificence of the provincial days, of men high in the opinion of their towns-people, of the reaching out to far lands and exotic splendors, he is expressing the stored-up experience of his race. His father died when Nathaniel was but four and the little family lived a secluded life with his mother. He was a handsome boy and quite devoted to reading, by an early accident which for a time prevented outdoor games. His first school was with Dr. Worcester, the lexicographer. In 1818 his mother moved to Raymond, Me., where her brother had bought land, and Hawthorne went to Bowdoin College. He entered college at the age of 17 in the same class with Longfellow. In the class above him was Franklin Pierce, afterward 12th President of the United States. On being graduated in 1825 Hawthorne determined upon literature as a profession, but his first efforts were without success. ‘Fanshawe’ was published anonymously in 1828, and shorter tales and sketches were without importance. Little need be said of these earlier years save to note that they were full of reading and observation. In 1836 he edited in Boston the AmericanMagazine for Useful and Entertaining Knowledge, but gained little from it save an introduction to ‘The Token,’ in which his tales first came to be known. Returning to Salem he lived a very secluded life, seeing almost no one (rather a family trait), and devoted to his thoughts and imaginations. He was a strong and powerful man, of excellent health and, though silent, cheerful, and a delightful companion when be chose. But intellectually he was of a separated and individual type, having his own extravagances and powers and submitting to no companionship in influence. In 1837 appeared ‘Twice Told Tales’ in book form: in a preface written afterward Hawthorne says that he was at this time “the obscurest man of letters in America.” Gradually he began to be more widely received. In 1839 he became engaged to Miss Sophia Peabody, but was not married for some years. In 1838 he was appointed to a place in the Boston custom house, but found that he could not easily save time enough for literature and was not very sorry when the change of administration put him out of office. In 1841 was founded the socialistic community at Brook Farm: it seemed to Hawthorne that here was a chance for a union of intellectual and physical work, whereby he might make a suitable home for his future wife. It failed to fulfil his expectations and Hawthorne withdrew from the experiment. In 1842 he was married and moved with his wife to the Old Manse at Concord just above the historic bridge. Here chiefly he wrote the ‘Mosses of an Old Manse’ (1846). In 1845 he published a second series of ‘Twice Told Tales’; in this year also the family moved to Salem, where he had received the appointment of surveyor at the custom house. As before, official work was a hindrance to literature; not till 1849 when he lost his position could he work seriously. He used his new-found leisure in carrying out a theme that had been long in his mind and produced ‘The Scarlet Letter’ in 1850. This, the first of his longer novels, was received with enthusiasm and at once gave him a distinct place in literature. He now moved to Lenox, Mass., where he began on ‘The House of Seven Gables,’ which was published in 1851. He also wrote ‘A Wonder-Book’ here, which in its way has become as famous as his more important work. In December 1851 he moved to West Newton, and shortly to Concord again, this time to the Wayside. At Newton he wrote ‘The Blithedale Romance.’ Having settled himself at Concord in the summer of 1852, his first literary work was to write the life of his college friend, Franklin Pierce, just nominated for the Presidency. This done he turned to ‘Tanglewood Tales,’ a volume not unlike the ‘Wonder-Book.’ In 1853 he was named consul to Liverpool: at first he declined the position, but finally resolved to take this opportunity to see something of Europe. He spent four years in England, and then a year in Italy. As before, he could write nothing while an official, and resigned in 1857 to go to Rome, where he passed the winter, and to Florence, where he received suggestions and ideas which gave him stimulus for literary work. The summer of 1858 he passed at Redcar, in Yorkshire, where he wrote ‘The Marble Faun.’ In June 1860 he sailed for America, where he returned to the Wayside. For a time he did little literary work; in 1863 he published ‘Our Old Home,’ a series of sketches of English life, and planned a new novel, ‘The Dolliver Romance,’ also called ‘Pansie.’ But though he suffered from no disease his vitality seemed relaxed; some unfortunate accidents had a depressing effect, and in the midst of a carriage trip into the White Mountains with his old friend, Franklin Pierce, he died suddenly at Plymouth, N. H., early in the morning, 19 May 1864.

The works of Hawthorne consist of novels, short stories, tales for children, sketches of life and travel and some miscellaneous pieces of a biographical or descriptive character. Besides these there were published after his death extracts from his notebooks. Of his novels ‘The Scarlet Letter’ is a story of old New England; it has a powerful moral idea at bottom, but it is equally strong in its presentation of life and character in the early days of Massachusetts. ‘House of the Seven Gables’ presents New England life of a later date; there is more of careful analysis and presentation of character and more description of life and manners, but less moral intensity. ‘The Blithedale Romance’ is less strong; Hawthorne seems hardly to grasp his subject. It makes the third in what may be called a series of romances presenting the molding currents of New England life: the first showing the factors of religion and sin, the second the forces of hereditary good and evil, and the third giving a picture of intellectual and emotional ferment in a society which had come from very different beginnings. ‘Septimius Felton,’ finished in the main but not published by Hawthorne, is a fantastic story dealing with the idea of immortality. It was put aside by Hawthorne when he began to write ‘The Dolliver Romance,’ of which he completed only the first chapters. ‘Dr. Grimshaw's Secret’ (published in 1882) is also not entirely finished. These three books represent a purpose that Hawthorne never carried out. He had presented New England life, with which the life of himself and his ancestry was so indissolubly connected, in three characteristic phases. He had traced New England history to its source. He now looked back across the ocean to the England he had learned to know, and thought of a tale that should bridge the gulf between the Old World and the New. But the stories are all incomplete and should be read only by the student. The same thing may be said of ‘Fanshawe,’ which was published anonymously early in Hawthorne's life and later withdrawn from circulation. ‘The Marble Faun’ presents to us a conception of the Old World at its oldest point. It is Hawthorne's most elaborate work, and if every one were familiar with the scenes so discursively described, would probably be more generally considered his best. Like the other novels its motive is based on the problem of evil, but we have not precisely atonement nor retribution, as in his first two novels. The story is one of development, a transformation of the soul through the overcoming of evil. The four novels constitute the foundation of Hawthorne's literary fame and character, but the collections of short stories do much to develop and complete the structure. They are of various kinds, as follows: (1) Sketches of current life or of history, as ‘Rills from the Town Pump,’ ‘The Village Uncle,’ ‘Main Street,’ ‘Old News.’ These are chiefly descriptive and have little story; there are about 20 of them. (2) Stories of old New England, as ‘The Gray Champion,’ ‘The Gentle Boy,’ ‘Tales of the Province House.’ These stories are often illustrative of some idea and so might find place in the next set. (3) Stories based upon some idea, as ‘Ethan Brand,’ which presents the idea of the unpardonable sin; ‘The Minister's Black Veil,’ the idea of the separation of each soul from its fellows; ‘Young Goodman Brown,’ the power of doubt in good and evil. These are the most characteristic of Hawthorne's short stories; there are about a dozen of them. (4) Somewhat different are the allegories, as ‘The Great Stone Face,’ ‘Rappacini's Daughter,’ ‘The Great Carbuncle.’ Here the figures are not examples or types, but symbols, although in no story is the allegory consistent. (5) There are also purely fantastic developments of some idea, as ‘The New Adam and Eve,’ ‘The Christmas Banquet,’ ‘The Celestial Railroad.’ These differ from the others in that there is an almost logical development of some fancy, as in case of the first the idea of a perfectly natural pair being suddenly introduced to all the conventionalities of our civilization. There are perhaps 20 of these fantasies. Hawthorne's stories from classical mythology, the ‘Wonder-Book’ and ‘Tanglewood Tales,’ belong to a special class of books, those in which men of genius have retold stories of the past in forms suited to the present. The stories themselves are set in a piece of narrative and description which gives the atmosphere of the time of the writer, and the old legends are turned from stately myths not merely to children's stories, but to romantic fancies. Mr. Pringle in ‘Tanglewood Fireside’ comments on the idea: “Eustace,” he says to the young college student who had been telling the stories to the children, “pray let me advise you never more to meddle with a classical myth. Your imagination is altogether Gothic and will inevitably Gothicize everything that you touch. The effect is like bedaubing a marble statue with paint. This giant, now! How can you have ventured to thrust his huge disproportioned mass among the seemly outlines of Grecian fable?” “I described the giant as he appeared to me,” replied the student, “And, sir, if you would only bring your mind into such a relation to these fables as is necessary in order to remodel them, you would see at once that an old Greek has no more exclusive right to them than a modern Yankee has. They are the common property of the world and of all time” (“Wonder-Book,” p. 135). ‘Grandfather's Chair’ was also written primarily for children and gives narratives of New England history, joined together by a running comment and narrative from Grandfather, whose old chair had come to New England, not in the Mayflower, but with John Winthrop and the first settlers of Boston. ‘Biographical Stories,’ in a somewhat similar framework, tells of the lives of Franklin, Benjamin West and others. It should be noted of these books that Hawthorne's writings for children were always written with as much care and thought as his more serious work. ‘Our Old Home’ was the outcome of that less remembered side of Hawthorne's genius which was a master of the details of circumstance and surroundings. The notebooks give us this also, but the American notebook has also rather a peculiar interest in giving us many of Hawthorne's first ideas which were afterward worked out into stories and sketches.

One element in Hawthorne's intellectual make-up was his interest in the observation of life and his power of description of scenes, manners and character. This is to be seen especially, as has been said, in his notebooks and in ‘Our Old Home,’ and in slightly modified form in the sketches noted above. These studies make up a considerable part of ‘Twice Told Tales’ and ‘Mosses from an Old Manse,’ and represent a side of Hawthorne's genius not always borne in mind. Had this interest been predominant in him we might have had in Hawthorne as great a novelist of our everyday life as James or Howells. In the ‘House of Seven Gables’ the power comes into full play; 100 pages hardly complete the descriptions of the simple occupations of a single uneventful day. In Hawthorne, however, this interest in the life around him was mingled with a great interest in history, as we may see, not only in the stories of old New England noted above, but in the descriptive passages of ‘The Scarlet Letter.’ Still we have not, even here, the special quality for which we know Hawthorne. Many great realists have written historical novels, for the same curiosity that absorbs one in the affairs of everyday may readily absorb one in the recreation of the past. In Hawthorne, however, was another element very different. His imagination often furnished him with conceptions having little connection with the actual circumstances of life. The fanciful developments of an idea noted above (5) have almost no relation to fact: they are “made up out of his own head.” They are fantastic enough, but generally they are developments of some moral idea and a still more ideal development of such conceptions was not uncommon in Hawthorne. ‘Rappacini's Daughter’ is an allegory in which the idea is given a wholly imaginary setting, not resembling anything that Hawthorne had ever known from observation. These two elements sometimes appear in Hawthorne's work separate and distinct just as they did in his life: sometimes he secluded himself in his room, going out only after nightfall; sometimes he wandered through the country observing life and meeting with everybody. But neither of these elements alone produced anything great, probably because for anything great we need the whole man. The true Hawthorne was a combination of these two elements, with various others of personal character, and artistic ability that cannot be specified here. The most obvious combination between these two elements, so far as literature is concerned, between the fact of external life and the idea of inward imagination, is by a symbol. The symbolist sees in everyday facts a presentation of ideas. Hawthorne wrote a number of tales that are practically allegories: ‘The Great Stone Face’ uses facts with which Hawthorne was familiar, persons and scenes that he knew, for the presentation of a conception of the ideal. His novels, too, are full of symbolism. ‘The Scarlet Letter’ itself is a symbol and the rich clothing of Little Pearl, Alice's posies among the Seven Gables, the old musty house itself, are symbols, Zenobia's flower, Hilda's doves. But this is not the highest synthesis of power, as Hawthorne sometimes felt himself, as when he said of ‘The Great Stone Face,’ that the moral was too plain and manifest for a work of art. However much we may delight in symbolism it must be admitted that a symbol that represents an idea only by a fanciful connection will not bear the seriousness of analysis of which a moral idea must be capable. A scarlet letter A has no real connection with adultery, which begins with A and is a scarlet sin only to such as know certain languages and certain metaphors. So Hawthorne aimed at a higher combination of the powers of which he was quite aware, and found it in figures and situations in which great ideas are implicit. In his finest work we have, not the circumstance before the conception or the conception before the circumstance, as in allegory. We have the idea in the fact, as it is in life, the two inseparable. Hester Prynne's life does not merely present to us the idea that the breaking of a social law makes one a stranger to society with its advantages and disadvantages. Hester is the result of her breaking that law. The story of Donatello is not merely a way of conveying the idea that the soul which conquers evil thereby grows strong in being and life. Donatello himself is such a soul growing and developing. We cannot get the idea without the fact, nor the fact without the idea. This is the especial power of Hawthorne, the power of presenting truth implicit in life. Add to this his profound preoccupation with the problem of evil in this world, with its appearance, its disappearance, its metamorphoses, and we have a due to Hawthorne's greatest works. In ‘The Scarlet Letter,’ ‘The House of Seven Gables,’ ‘The Marble Faun,’ ‘Ethan Brand,’ ‘The Gray Champion,’ the ideas cannot be separated from the personalities which express them. It is this which constitutes Hawthorne's lasting power in literature. His observation is interesting to those that care for the things that he describes, his fancy amuses, or charms or often stimulates our ideas. His short stories are interesting to a student of literature because they did much to give a definite character to a literary form which has since become of great importance. His novels are exquisite specimens of what he himself called the romance, in which the figures and scenes are laid in a world a little more poetic than that which makes up our daily surrounding. But Hawthorne's really great power lay in his ability to depict life so that we are made keenly aware of the dominating influence of moral motive and moral law.

Passages From The American Note-Books

Introductory Note To The American Note-Books.

[by George Parsons Lathrop, 1883]

AFTERthe death of Hawthorne, the desire for a biography was so strongly expressed, both among his friends and by the public at large, that his widow was prompted to supply in part the information of which there was obviously much need. As she has explained in her Preface to the "English Note-Books," Hawthorne's own wish was that no one should attempt to write his life. Lapsing time and the perspective imparted by the world's settled estimate of his genius, have shown that no final restriction ought to be imposed on the natural instinct and right of students and sincere admirers to seek a more personal knowledge of the author than his imaginative writings could yield. His preference, respecting the publication of a biography, was not, indeed, an absolute injunction; but it is not strange that Mrs. Hawthorne should have chosen to conform to it. In default, then, of the life which she was unwilling to countenance or undertake, she resolved to offer these extracts from his memorandum-books or diaries, supplemented by portions of his letters. They were designed to present some suggestion of his mode of life and mental habit, and to counteract a false impression of his personality which the sombre tone of his fictions had spread abroad.

Thepassages relating to his American life having been well received, and as it was necessary, in order to complete an outline of the later career, that his European experience should be presented though a similar medium, the "English Note-Books" and the "French and Italian Note-Books" were published in 1870 and 1871, respectively.

Ithas been remarked by a recent writer, in a light monograph on Hawthorne, that the Note-Books read like a series of rather dull letters, written by the romancer to himself, during a term of years. Whatever degree of acumen this remark may indicate in the maker, it shows clearly that he has left out of account (if he took pains to examine at all) the manner in which the notes came into existence and the circumstances of their publication. When Hawthorne was about twelve years of age, it is supposed that a blank volume was given him by one of his uncles, "with the advice"--so runs an inscription purporting to have been copied from the first leaf of this book--"to write out his thoughts, some every day, in as good words as he can, upon any and all subjects, as it is one of the best means of his securing for mature years command of thought and language." The habit of keeping a journal as an exercise, and of describing ordinary occurrences day by day, with the impression made upon him by them, was thus formed very early in life, and partially accounts for the ease and precision of his language in the Note-Books now included among his published works. This circumstance will also explain how it became a second nature with theauthor, even in maturer years, to confide his daily observations to the pages of some private register, and often to enter there details which, to the careless glance, appear unaccountably slight. In the first half of this century, the custom of keeping regular diaries and voluminous journals was much more general than at the present day, owing to the greater leisureliness of life at that time. People recorded in them, as those do who still maintain the custom, the smallest transactions of each twenty-four hours; and Hawthorne himself, during some years, wrote similar memoranda in pocket-books, which allowed only a brief space to each day. The manuscript books from which the published passages have been taken were not of that sort, but were evidently used as media for the preservation of passing impressions, which might or might not prove subsequently valuable for reference, in composition. Frequently the purpose of an entry may have been merely to deepen, by the act of writing, some fleeting association of a sight or sound with an inward train of thought which does not appear in the written words at all; as in that sentence, which has been cited as an evidence of mental vacancy, "The smell of peat-smoke in the autumnal air is very pleasant." The "American Note-Books," in fine, should be taken for precisely what they are, and no more; that is, repositories of the most informal kind, for such fragments of observation and reflection as the writer chose to commit to them for his own purposes; as the results, too, of an early-formed taste for exercising his pen upon the simplest objects of notice that surrounded him. Bearing in mind the vogue of journal-writing at that period, we shall not find it surprising if items occur which do not possess universal interest, but seem to have founda place through the inertia of a long-established habit of making notes. Living for many years in a solitary way, and always invested with a peculiar sensitive and shy reserve, Hawthorne would sometimes naturally let fall from the point of his pen, in the companionship of his journal, passing remarks which another person would have made in conversation; no permanent importance being attached to them in either case.

Fromtheir character and origin, it is impossible that the Note-Books should furnish a complete picture of Hawthorne's mind and qualities, though they convey hints of them. The records themselves were scattered through books of various sizes, sometimes only half-filled and sometimes labelled "Scrap-Book." Probably the idea that they would be presented in print to the public never even occurred to the writer. Nor is the absence of the author''s opinions on literary matters at all extraordinary. Surprise has been expressed that the fact of his reading a volume of Rabelais should be mentioned, without any accompanying disquisition touching Rabelais. It was no part of Hawthorne's aim as an author to analyze other authors; and it is doubtful whether he greatly cared to form elaborate critical estimates of them, although it is manifest enough from his remarks on his own work, in his prefaces, that he could characterize and discuss literary art with fine penetration. His judgment of Anthony Trollope, given in a published letter, also exhibits his keen appreciation of a widely different kind of work. But even had he chosen to make such estimates, he would not have incorporated them in a journal kept for an entirely different purpose; a journal which obviously cannot be assumed with any justice to mirror his whole intellectual life. So that, while the"American Note-Books" contain many traces of his personality, throw some light on his habit of observing common things, and intimate the outward conditions of his modest course of living, they contain few of those deep reflections which come to light in his works of imagination; and they must not be looked to for a revelation of the entire man. In basing opinions upon them, it is well to remember, and apply in this case also, what Hawthorne once said in a letter to Mr. Fields:--

"An old Quaker wrote me, the other day, that he had been reading my Introduction to the 'Mosses' and the 'Scarlet Letter,' and felt as if he knew me better than his best friend; but I think he considerably overestimates the extent of his intimacy with me."

Thefinish and deliberation of the style in these fragmentary chronicles, fitly known under the name of Note-Books, are very likely to mislead any one who does not constantly recall the fact that they were writtencurrente calamo, and merely as superficial memoranda, beneath which lay the author's deeper meditation, always reserved in essence until he was ready to precipitate it in the plastic forms of fiction. Speaking of "Our Old Home," which--charming though it be to the reader--was drawn almost wholly from the surface deposit of his "English Note-Books," Hawthorne said: "It is neither a good nor a weighty book." And this, indirectly, shows that he did not regard the journals, as concentrating the profounder substance of his genius.

Theseries of passages from the "American Note-Books" covers the space of eighteen years, almost to a day; the extracts running from June 15, 1835, toJune 9, 1853; and in a detached way it represents the main part of Hawthorne's career throughout the period of his rise from obscurity to fame, purely as a growth of American soil and conditions, before he had ever set foot in Europe.

Doubthas been thrown upon the correctness of one date in the printed volume, that of September 7, 1835, describing "A drive to Ipswich with B----." The person referred to as "B----, is still living, and did not become acquainted with Hawthorne until 1845,--ten years later than the date of the entry in question. It is possible that an error of transcription may have occurred, owing to indistinctness of chirography or the confused manner of keeping these early Note-Books; but in the main the chronology may be relied upon as accurate. Two other passages require a brief explanation. Under date of August 31, 1836, is printed the sentence: "In this dismal chamber FAME was won." (Salem, Union Street.) Again, one reads: "Salem, Oct. 4th, Union Street [Family Mansion].--. . . Here I sit in my old accustomed chamber. . . .Here I have written my tales," etc. The reference in both instances is to Herbert Street, Salem; and the simple explanation of another street-name being substituted is as follows. Hawthorne was born in a house on Union Street, Salem. After the death of his father, a ship-captain, at Surinam, in 1808, his mother removed "to the house of her father in Herbert Street, the next one eastward from Union. The land belonging to this ran through to Union Street, adjoining the house they had left; and from his top-floor study here, in later years, Hawthorne could look down on the less lofty roof under which he was born. The Herbert Street house, however, was spoken of as being onUnion Street." Hence, in the two passages above cited, "Herbert Street" should be put in the place of "Union Street," if it be desired to identify the exact locality. Hawthorne wrote his first stories in the Herbert Street house; but that house, the family mansion (now, through the indifference of his townsmen, become a tenement-house), was always referred to by members of the family as being on Union Street.

Hereand there passages of the original record have been omitted in the Note-Books as published by Mrs. Hawthorne; but the most vital and significant portions are retained in the printed version; and these, in the collected works, are all that will be given to the public.

1835

SALEM,June15, 1835.--A walk down to the Juniper. The shore of the coves strewn with bunches of sea-weed, driven in by recent winds. Eel-grass, rolled and bundled up, and entangled with it,--large marine vegetables, of an olive-color, with round, slender, snake-like stalks, four or five feet long, and nearly two feet broad: these are the herbage of the deep sea. Shoals of fishes, at a little distance from the shore, discernible by their fins out of water. Among the heaps of sea-weed there were sometimes small pieces of painted wood, bark, and other driftage. On the shore, with pebbles of granite, there were round or oval pieces of brick, which the waves had rolled about till they resembled a natural mineral. Huge stones tossed about, in every variety of confusion, some shagged all over with sea-weed, others only partly covered, others bare. The old ten-gun battery, at the outer angle of the Juniper, very verdant, and besprinkled with white-weed, clover, and buttercups. The juniper-trees are very aged and decayed and moss-grown. The grass about the hospital is rank, being trodden, probably, by nobody but myself. There is a representation of a vessel under sail, cut with a penknife, on the corner of the house.

Returningby the almshouse, I stopped a good while to look at the pigs,--a great herd,--who seemed to be just finishing their suppers. They certainly are types of unmitigated sensuality,--some standing in the trough, in the midst of their own and others' victuals,--some thrusting their noses deep into the food,--some rubbing their backs against a post,--some huddled together between sleeping and waking, breathing hard,--all wallowing about; a great boar swaggering round, and a big sow waddling along with her huge paunch. Notwithstanding the unspeakable defilement with which these strange sensualists spice all their food, they seem to have a quick and delicate sense of smell. What ridiculous-looking animals! Swift himself could not have imagined anything nastier than what they practise by the mere impulse of natural genius. Yet the Shakers keep their pigs very clean, and with great advantage. The legion of devils in the herd of swine,--what a scene it must have been!

Sundayevening, going by the jail, the setting sun kindled up the windows most cheerfully; as if there were a bright, comfortable light within its darksome stone wall.

June18th.--A walk in North Salem in the decline of yesterday afternoon,--beautiful weather, bright, sunny, with a western or northwestern wind just cool enough, and a slight superfluity of heat. The verdure, both of trees and grass, is now in its prime, the leaves elastic, all life. The grass-fields are plenteously bestrewn with white-weed, large spaces looking as white as a sheet of snow, at a distance, yet with an indescribably warmer tinge than snow,--living white,intermixed with living green. The hills and hollows beyond the Cold Spring copiously shaded, principally with oaks of good growth, and some walnut-trees, with the rich sun brightening in the midst of the open spaces, and mellowing and fading into the shade,--and single trees, with their cool spot of shade, in the waste of sun: quite a picture of beauty, gently picturesque. The surface of the land is so varied, with woodland mingled, that the eye cannot reach far away, except now and then in vistas perhaps across the river, showing houses, or a church and surrounding village, in Upper Beverly. In one of the sunny bits of pasture, walled irregularly in with oak-shade, I saw a gray mare feeding, and, as I drew near, a colt sprang up from amid the grass,--a very small colt. He looked me in the face, and I tried to startle him, so as to make him gallop; but he stretched his long legs, one after another, walked quietly to his mother, and began to suck,--just wetting his lips, not being very hungry. Then he rubbed his head, alternately, with each hind leg. He was a graceful little beast.

Ibathed in the cove, overhung with maples and walnuts, the water cool and thrilling. At a distance it sparkled bright and blue in the breeze and sun. There were jelly-fish swimming about, and several left to melt away on the shore. On the shore, sprouting amongst the sand and gravel, I found samphire, growing somewhat like asparagus. It is an excellent salad at this season, salt, yet with an herb-like vivacity, and very tender. I strolled slowly through the pastures, watching my long shadow making grave, fantastic gestures in the sun. It is a pretty sight to see the sunshine brightening the entrance of a road which shortly becomes deeply overshadowed by trees on both sides.At the Cold Spring, three little girls, from six to nine, were seated on the stones in which the fountain is set, and paddling in the water. It was a pretty picture, and would have been prettier, if they had shown bare little legs, instead of pantalets. Very large trees overhung them, and the sun was so nearly gone down that a pleasant gloom made the spot sombre, in contrast with these light and laughing little figures. On perceiving me, they rose up, tittering among themselves. It seemed that there was a sort of playful malice in those who first saw me; for they allowed the other to keep on paddling, without warning her of my approach. I passed along, and heard them come chattering behind.

June22d.--I rode to Boston in the afternoon with Mr. Proctor. It was a coolish day, with clouds and intermitting sunshine, and a pretty fresh breeze. We stopped about an hour at the Maverick House, in the sprouting branch of the city, at East Boston,--a stylish house, with doors painted in imitation of oak; a large bar; bells ringing; the bar-keeper calls out, when a bell rings, "Number --- "; then a waiter replies, "Number --- answered"; and scampers up stairs. A ticket is given by the hostler, on taking the horse and chaise, which is returned to the bar-keeper when the chaise is wanted. The landlord was fashionably dressed, with the whitest of linen, neatly plaited, and as courteous as a Lord Chamberlain. Visitors from Boston thronging the house,--some standing at the bar, watching the process of preparing tumblers of punch,--others sitting at the windows of different parlors,--some with faces flushed, puffing cigars. The bill of fare for the day was stuck up beside thebar. Opposite this principal hotel there was another, called "The Mechanics," which seemed to be equally thronged. I suspect that the company were about on a par in each; for at the Maverick House, though well dressed, they seemed to be merely Sunday gentlemen,--mostly young fellows,--clerks in dry-goods stores being the aristocracy of them. One, very fashionable in appearance, with a handsome cane, happened to stop by me and lift up his foot, and I noticed that the sole of his boot (which was exquisitely polished) was all worn out. I apprehend that some such minor deficiencies might have been detected in the general showiness of most of them. There were girls, too, but not pretty ones, nor, on the whole, such good imitations of gentility as the young men. There were as many people as are usually collected at a muster, or on similar occasions, lounging about, without any apparent enjoyment; but the observation of this may serve me to make a sketch of the mode of spending the Sabbath by the majority of unmarried, young, middling-class people, near a great town. Most of the people had smart canes and bosom-pins.

Crossingthe ferry into Boston, we went to the City Tavern, where the bar-room presented a Sabbath scene of repose,--stage-folk lounging in chairs half asleep, smoking cigars, generally with clean linen and other niceties of apparel, to mark the day. The doors and blinds of an oyster and refreshment shop across the street were closed, but I saw people enter it. There were two owls in a back court, visible through a window of the bar-room,--speckled gray, with dark-blue eyes,--the queerest-looking birds that exist,--so solemn and wise,--dozing away the day, much like the rest of the people, only that they looked wiserthan any others. Their hooked beaks looked like hooked noses. A dull scene this. A stranger, here and there, poring over a newspaper. Many of the stage-folk sitting in chairs on the pavement, in front of the door.

Wewent to the top of the hill which formed part of Gardiner Greene's estate, and which is now in the process of levelling, and pretty much taken away, except the highest point, and a narrow path to ascend to it. It gives an admirable view of the city, being almost as high as the steeples and the dome of the State House, and overlooking the whole mass of brick buildings and slated roofs, with glimpses of streets far below. It was really a pity to take it down. I noticed the stump of a very large elm, recently felled. No house in the city could have reared its roof so high as the roots of that tree, if indeed the church-spires did so.

Onour drive home we passed through Charlestown. Stages in abundance were passing the road, burdened with passengers inside and out; also chaises and barouches, horsemen and footmen. We are a community of Sabbath-breakers!

August31st.--A drive to Nahant yesterday afternoon. Stopped at Rice's, and afterwards walked down to the steamboat wharf to see the passengers land. It is strange how few good faces there are in the world, comparatively to the ugly ones. Scarcely a single comely one in all this collection. Then to the hotel. Barouches at the doors, and gentlemen and ladies going to drive, and gentlemen smoking round the piazza. The bar-keeper had one of Benton's mint-drops for a bosom-brooch! It made a very handsome one. I crossed the beach for home about sunset. The tidewas so far down as just to give me a passage on the hard sand, between the sea and the loose gravel. The sea was calm and smooth, with only the surf-waves whitening along the beach. Several ladies and gentlemen on horseback were cantering and galloping before and behind me.

Ahint of a story,--some incident which should bring on a general war; and the chief actor in the incident to have something corresponding to the mischief he had caused.

September7th.--A drive to Ipswich with B----. At the tavern was an old, fat, country major, and another old fellow, laughing and playing off jokes on each other,--one tying a ribbon upon the other's hat. One had been a trumpeter to the major's troop. Walking about town, we knocked, for a whim, at the door of a dark old house, and inquired if Miss Hannah Lord lived there. A woman of about thirty came to the door, with rather a confused smile, and a disorder about the bosom of her dress, as if she had been disturbed while nursing her child. She answered us with great kindness.

Enteringthe burial-ground, where some masons were building a tomb, we found a good many old monuments, and several covered with slabs of red freestone or slate, and with arms sculptured on the slab, or an inlaid circle of slate. On one slate gravestone, of the Rev. Nathl. Rogers, there was a portrait of that worthy, about a third of the size of life, carved in relief, with his cloak, band, and wig, in excellent preservation, all the buttons of his waistcoat being cut with great minuteness,--the minister's nose being ona level with his cheeks. It was an upright gravestone. Returning home, I held a colloquy with a young girl about the right road. She had come out to feed a pig, and was a little suspicious that we were making fun of her, yet answered us with a shy laugh and good-nature,--the pig all the time squealing for his dinner.

Displayedalong the walls, and suspended from the pillars of the original King's Chapel, were coats of arms of the king, the successive governors, and other distinguished men. In the pulpit there was an hour-glass on a large and elaborate brass stand. The organ was surmounted by a gilt crown in the centre, supported by a gilt mitre on each side. The governor's pew had Corinthian pillars, and crimson damask tapestry. In 1727 it was lined with china, probably tiles.

SaintAugustin, at mass, charged all that were accursed to go out of the church. "Then a dead body arose, and went out of the church into the churchyard, with a white cloth on its head, and stood there till mass was over. It was a former lord of the manor, whom a curate had cursed because he refused to pay his tithes. A justice also commanded the dead curate to arise, and gave him a rod; and the dead lord, kneeling, received penance thereby." He then ordered the lord to go again to his grave, which he did, and fell immediately to ashes. Saint Augustin offered to pray for the curate, that he might remain on earth to confirm men in their belief; but the curate refused, because he was in the place of rest.

Asketch to be given of a modern reformer,--atype of the extreme doctrines on the subject of slaves, cold water, and other such topics. He goes about the streets haranguing most eloquently, and is on the point of making many converts, when his labors are suddenly interrupted by the appearance of the keeper of a mad-house, whence he has escaped. Much may be made of this idea.

Achange from a gay young girl to an old woman; the melancholy events, the effects of which have clustered around her character, and gradually imbued it with their influence, till she becomes a lover of sick-chambers, taking pleasure in receiving dying breaths and in laying out the dead; also having her mind full of funeral reminiscences, and possessing more acquaintances beneath the burial turf than above it.

Awell-concerted train of events to be thrown into confusion by some misplaced circumstance, unsuspected till the catastrophe, yet exerting its influence from beginning to end.

Onthe common, at dusk, after a salute from two field-pieces, the smoke lay long and heavily on the ground, without much spreading beyond the original space over which it had gushed from the guns. It was about the height of a man. The evening clear, but with an autumnal chill.

Theworld is so sad and solemn, that things meant in jest are liable, by an overpowering influence, to become dreadful earnest,--gayly dressed fantasies turning to ghostly and black-clad images of themselves.

Astory, the hero of which is to be represented as naturally capable of deep and strong passion, and looking forward to the time when he shall feel passionate love, which is to be the great event of his existence. But it so chances that he never falls in love, and although he gives up the expectation of so doing, and marries calmly, yet it is somewhat sadly, with sentiments merely of esteem for his bride. The lady might be one who had loved him early in life, but whom then, in his expectation of passionate love, he had scorned.

Thescene of a story or sketch to be laid within the light of a street-lantern; the time, when the lamp is near going out; and the catastrophe to be simultaneous with the last flickering gleam.

Thepeculiar weariness and depression of spirits which is felt after a day wasted in turning over a magazine or other light miscellany, different from the state of the mind after severe study; because there has been no excitement, no difficulties to be overcome, but the spirits have evaporated insensibly.

Torepresent the process by which sober truth gradually strips off all the beautiful draperies with which imagination has enveloped a beloved object, till from an angel she turns out to be a merely ordinary woman. This to be done without caricature, perhaps with a quiet humor interfused, but the prevailing impression to be a sad one. The story might consist of the various alterations in the feelings of the absent lover, caused by successive events that display the true character of his mistress; and the catastrophe should takeplace at their meeting, when he finds himself equally disappointed in her person; or the whole spirit of the thing may here be reproduced.

Lastevening, from the opposite shore of the North River, a view of the town mirrored in the water, which was as smooth as glass, with no perceptible tide or agitation, except a trifling swell and reflux on the sand, although the shadow of the moon danced in it. The picture of the town perfect in the water,--towers of churches, houses, with here and there a light gleaming near the shore above, and more faintly glimmering under water,--all perfect, but somewhat more hazy and indistinct than the reality. There were many clouds flitting about the sky; and the picture of each could be traced in the water,--the ghost of what was itself unsubstantial. The rattling of wheels heard long and far through the town. Voices of people talking on the other side of the river, the tones being so distinguishable in all their variations that it seemed as if what was there said might be understood; but it was not so.

Twopersons might be bitter enemies through life, and mutually cause the ruin of one another, and of all that were dear to them. Finally, meeting at the funeral of a grandchild, the offspring of a son and daughter married without their consent,--and who, as well as the child, had been the victims of their hatred,--they might discover that the supposed ground of the quarrel was altogether a mistake, and then be wofully reconciled.

Twopersons, by mutual agreement, to make theirwills in each other's favor, then to wait impatiently for one another's death, and both to be informed of the desired event at the same time. Both, in most joyous sorrow, hasten to be present at the funeral, meet, and find themselves both hoaxed.

Thestory of a man, cold and hard-hearted, and acknowledging no brotherhood with mankind. At his death they might try to dig him a grave, but, at a little space beneath the ground, strike upon a rock, as if the earth refused to receive the unnatural son into her bosom. Then they would put him into an old sepulchre, where the coffins and corpses were all turned to dust, and so he would be alone. Then the body would petrify; and he having died in some characteristic act and expression, he would seem, through endless ages of death, to repel society as in life, and no one would be buried in that tomb forever.

Cannontransformed to church-bells.

Aperson, even before middle age, may become musty and faded among the people with whom he has grown up from childhood; but, by migrating to a new place, he appears fresh with the effect of youth, which may be communicated from the impressions of others to his own feelings.

Inan old house, a mysterious knocking might be heard on the wall, where had formerly been a door-way, now bricked up.

Itmight be stated, as the closing circumstance of a tale, that the body of one of the characters had been petrified, and still existed in that state.

Ayoung man to win the love of a girl, without any serious intentions, and to find that in that love, which might have been the greatest blessing of his life, he had conjured up a spirit of mischief which pursued him throughout his whole career,--and this without any revengeful purposes on the part of the deserted girl.

Twolovers, or other persons, on the most private business, to appoint a meeting in what they supposed to be a place of the utmost solitude, and to find it thronged with people.

October17th.--Some of the oaks are now a deep brown red; others are changed to a light green, which, at a little distance, especially in the sunshine, looks like the green of early spring. In some trees, different masses of the foliage show each of these hues. Some of the walnut-trees have a yet more delicate green. Others are of a bright sunny yellow.

Mr.----was married to Miss ---- last Wednesday. Yesterday Mr. Brazer, preaching on the comet, observed that not one, probably, of all who heard him, would witness its reappearance. Mrs.---- shed tears. Poor soul! she would be contented to dwell in earthly love to all eternity!

Sometreasure or other thing to be buried, and a tree planted directly over the spot, so as to embrace it with its roots.

Atree, tall and venerable, to be said by tradition to have been the staff of some famous man, who happened to thrust it into the ground, where it took root.

Afellow without money, having a hundred and seventy miles to go, fastened a chain and padlock to his legs, and lay down to sleep in a field. He was apprehended, and carried gratis to a jail in the town whither he desired to go.

Anold volume in a large library,--every one to be afraid to unclasp and open it, because it was said to be a book of magic.

Aghost seen by moonlight; when the moon was out, it would shine and melt through the airy substance of the ghost, as through a cloud.

Prideaux,Bishop of Worcester, during the sway of the Parliament, was forced to support himself and his family by selling his household goods. A friend asked him, "How doth your lordship?" "Never better in my life," said the Bishop, "only I have too great a stomach; for I have eaten that little plate which the sequestrators left me. I have eaten a great library of excellent books. I have eaten a great deal of linen, much of my brass, some of my pewter, and now I am come to eat iron; and what will come next I know not."

Ascold and a blockhead,--brimstone and wood,--a good match.

Tomake one's own reflection in a mirror the subject of a story.

Ina dream to wander to some place where may be heard the complaints of all the miserable on earth.

Somecommon quality or circumstance that should bring together people the most unlike in all other respects, and make a brotherhood and sisterhood of them,--the rich and the proud finding themselves in the same category with the mean and the despised.

Aperson to consider himself as the prime mover of certain remarkable events, but to discover that his actions have not contributed in the least thereto. Another person to be the cause, without suspecting it.

October25th.--A person or family long desires some particular good. At last it comes in such profusion as to be the great pest of their lives.

Aman, perhaps with a persuasion that he shall make his fortune by some singular means, and with an eager longing so to do, while digging or boring for water, to strike upon a salt-spring.

Tohave one event operate in several places,--as, for example, if a man's head were to be cut off in one town, men's heads to drop off in several towns.

Followout the fantasy of a man taking his life by instalments, instead of at one payment,--say ten years of life alternately with ten years of suspended animation.

Sentimentsin a foreign language, which merely convey the sentiment without retaining to the reader any graces of style or harmony of sound, have somewhat of the charm of thoughts in one's own mind that have not yet been put into words. No possible words thatwe might adapt to them could realize the unshaped beauty that they appear to possess. This is the reason that translations are never satisfactory,--and less so, I should think, to one who cannot than to one who can pronounce the language.

Aperson to be writing a tale, and to find that it shapes itself against his intentions; that the characters act otherwise than he thought; that unforeseen events occur; and a catastrophe comes which he strives in vain to avert. It might shadow forth his own fate,--he having made himself one of the personages.

Itis a singular thing, that, at the distance, say, of five feet, the work of the greatest dunce looks just as well as that of the greatest genius,--that little space being all the distance between genius and stupidity.

Mrs.Sigourney says, after Coleridge, that "poetry has been its own exceeding great reward." For the writing, perhaps; but would it be so for the reading?

Fourprecepts: To break off customs; to shake off spirits ill-disposed; to meditate on youth; to do nothing against one's genius.

1836

Salem,August31, 1836.--A walk, yesterday, down to the shore, near the hospital. Standing on the old grassy battery, that forms a semicircle, and looking seaward. The sun not a great way above the horizon, yet so far as to give a very golden brightness, when it shone out. Clouds in the vicinity of the sun, and nearly all the rest of the sky covered with cloudsin masses, not a gray uniformity of cloud. A fresh breeze blowing from land seaward. If it had been blowing from the sea, it would have raised it in heavy billows, and caused it to dash high against the rocks. But now its surface was not all commoved with billows; there was only roughness enough to take off the gleam, and give it the aspect of iron after cooling. The clouds above added to the black appearance. A few sea-birds were flitting over the water, only visible at moments, when they turned their white bosoms towards me,--as if they were then first created. The sunshine had a singular effect. The clouds would interpose in such a manner that some objects were shaded from it, while others were strongly illuminated. Some of the islands lay in the shade, dark and gloomy, while others were bright and favored spots. The white light-house was sometimes very cheerfully marked. There was a schooner about a mile from the shore, at anchor, laden apparently with lumber. The sea all about her had the black, iron aspect which I have described; but the vessel herself was alight. Hull, masts, and spars were all gilded, and the rigging was made of golden threads. A small white streak of foam breaking around the bows, which ware towards the wind. The shadowiness of the clouds overhead made the effect of the sunlight strange, where it fell.

September.--Theelm-trees have golden branches intermingled with their green already, and so they had on the first of the month.

Topicture the predicament of worldly people, if admitted to paradise.

Asthe architecture of a country always follows the earliest structures, American architecture should be a refinement of the log-house. The Egyptian is so of the cavern and mound; the Chinese, of the tent; the Gothic, of overarching trees; the Greek, of a cabin.

"Though we speak nonsense, God will pick out the meaning of it,"--an extempore prayer by a New England divine.

Inold times it must have been much less customary than now to drink pure water. Walker emphatically mentions, among the sufferings of a clergyman's wife and family in the Great Rebellion, that they were forced to drink water, with crab-apples stamped in it to relish it.

Mr.Kirby, author of a work on the History, Habits, and Instincts of Animals, questions whether there may not be an abyss of waters within the globe, communicating with the ocean, and whether the huge animals of the Saurian tribe--great reptiles, supposed to be exclusively antediluvian, and now extinct--may not be inhabitants of it. He quotes a passage from Revelation, where the creatures under the earth are spoken of as distinct from those of the sea, and speaks of a Saurian fossil that has been found deep in the subterranean regions. He thinks, or suggests, that these may be the dragons of Scripture.

Theelephant is not particularly sagacious in the wild state, but becomes so when tamed. The fox directly the contrary, and likewise the wolf.

Amodern Jewish adage,--"Let a man clothe himself beneath his ability, his children according to his ability, and his wife above his ability."

Itis said of the eagle, that, in however long a flight, he is never seen to clap his wings to his sides. He seems to govern his movements by the inclination of his wings and tail to the wind, as a ship is propelled by the action of the wind on her sails.

Inold country-houses in England, instead of glass for windows, they used wicker, or fine strips of oak disposed checkerwise. Horn was also used. The windows of princes and great noblemen were of crystal; those of Studley Castle, Holinshed says, of beryl. There were seldom chimneys; and they cooked their meats by a fire made against an iron back in the great hall. Houses, often of gentry, were built of a heavy timber frame, filled up with lath and plaster. People slept on rough mats or straw pallets, with a round log for a pillow; seldom better beds than a mattress, with a sack of chaff for a pillow.

October25th.--A walk yesterday through Dark Lane, and home through the village of Danvers. Landscape now wholly autumnal. Saw an elderly man laden with two dry, yellow, rustling bundles of Indian corn-stalks,--a good personification of Autumn. Another man hoeing up potatoes. Rows of white cabbages lay ripening. Fields of dry Indian corn. The grass has still considerable greenness. Wild rose-bushes devoid of leaves, with their deep, bright red seed-vessels. Meeting-house in Danvers seen at a distance, with the sun shining through the windows of its belfry.Barberry-bushes,--the leaves now of a brown red, still juicy and healthy; very few berries remaining, mostly frost-bitten and wilted. All among the yet green grass, dry stalks of weeds. The down of thistles occasionally seen flying through the sunny air.

Inthis dismal chamber FAME was won. (Salem, Union Street.)

Those who are very difficult in choosing wives seem as if they would take none of Nature's ready-made works, but want a woman manufactured particularly to their order.

Acouncil of the passengers in a street: called by somebody to decide upon some points important to him.

Everyindividual has a place to fill in the world, and is important, in some respects, whether he chooses to be so or not.

AThanksgiving dinner. All the miserable on earth are to be invited,--as the drunkard, the bereaved parent, the ruined merchant, the broken-hearted lover, the poor widow, the old man and woman who have outlived their generation, the disappointed author, the wounded, sick, and broken soldier, the diseased person, the infidel, the man with an evil conscience, little orphan children or children of neglectful parents, shall be admitted to the table, and many others. The giver of the feast goes out to deliver his invitations. Some of the guests he meets in the streets, some he knocks for at the doors of their houses. The description