14,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Fyfield Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837-1909) was one of English poetry's truly distinctive stylists, a supreme technician, with an unbelievable mastery over sound (Edith Sitwell). He was one of the major poets of the Victorian era, and almost certainly the most provocative. His pagan sensualism and masochistic fantasies thrilled and outraged his readers, while the musical textures of his verse both delighted and unsettled. In this new anthology of his finest verse, Swinburne's most celebrated collection, the Poems and Ballads of 1866, is represented much more fully than in earlier selections, and ample extracts are given from his later masterpiece, Tristram of Lyonesse (1882). Also included are generous passages from the best of Swinburne's five-act tragedies, which have not been reprinted for nearly a century. Above all, this book is designed to make Swinburne, once again, a poet to be read widely for pleasure. No one else has made such music in English', wrote Ezra Pound; The splendid lines mount up in one's memory and overwhelm any minute restrictions of one's praise'.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Selected Verse

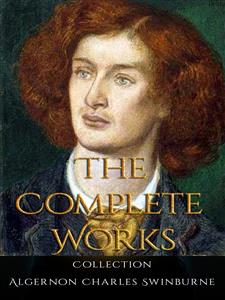

ALGERNON CHARLES SWINBURNE was born in London in 1837 to an aristocratic family. As an undergraduate in Oxford, he made the acquaintance of D. G. Rossetti, William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, all of whom would influence his work. Returning to London without having completed his degree, he continued to associate with many leading figures of the Aesthetic Movement. The dramatic poem Atalanta in Calydon (1865) established his literary reputation, and he followed this success with a collection, Poems and Ballads (1866), which made him the most controversial English poet of the day. Many other volumes followed, including Songs Before Sunrise (1871), two more series of Poems and Ballads (1878 and 1889), the Arthurian epic Tristram of Lyonesse (1882), and several plays. Swinburne was also an important critic of modern and early-modern literature. During his two decades in London (1860-1879), his bohemian lifestyle was infamous, and the period was marred by ill-health and alcoholism. In 1879 his friend Theodore Watts-Dunton brought him to his own home in Putney, where he could be looked after. Here Swinburne remained, still writing, until his death in 1909.

ALEX WONG studied English literature at the University of Cambridge, completing his doctoral research on Renaissance ‘kissing poems’. He has published essays and articles on English and Latin poetry.

FyfieldBooks aim to make available some of the great classics of British and European literature in clear, affordable formats, and to restore often neglected writers to their place in literary tradition.

FyfieldBooks take their name from the Fyfield elm in Matthew Arnold’s ‘Scholar Gypsy’ and ‘Thyrsis’. The tree stood not far from the village where the series was originally devised in 1971.

Roam on! The light we sought is shining still.

Dost thou ask proof? Our tree yet crowns the hill,

Our Scholar travels yet the loved hill-side

from ‘Thyrsis’

A. C. Swinburne

Selected Verse

EDITED AND INTRODUCED BY

ALEX WONG

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

FromATALANTA IN CALYDON (1865)

The First Choral Song

Althaea’s Scorn of Prayer

The Second Choral Song

Meleager rejects his Mother’s Counsel concerning Atalanta

The Fourth Choral Song

The Herald reports the Slaying of the Boar

From the Sixth Choral Song

Althaea’s Final Words, having Burnt the Brand

The Death of Meleager

FromCHASTELARD (1865)

From Act 1, scene 3

The Queen and Chastelard (I).

From Act 2, scene 1

The Queen and Chastelard (II).

From Act 3, scene 1

Chastelard steals into the Queen’s Bedchamber.

FromPOEMS AND BALLADS, FIRST SERIES (1866)

A Ballad of Life

A Ballad of Death

Laus Veneris

The Triumph of Time

Les Noyades

A Leave-Taking

Anactoria

Hymn to Proserpine

Ilicet

Hermaphroditus

Fragoletta

Rondel

Satia Te Sanguine

A Lamentation

Anima Anceps

In the Orchard

A Match

Faustine

Rococo

Stage Love

The Leper

A Ballad of Burdens

Rondel

Before the Mirror

Before Dawn

Dolores

The Garden of Proserpine

Before Parting

The Sundew

Félise

Hendecasyllabics

Sapphics

At Eleusis

August

St. Dorothy

The Two Dreams

The King’s Daughter

After Death

The Year of Love

FromSONGS BEFORE SUNRISE (1871)

Prelude

Hertha

Before a Crucifix

Genesis

The Oblation

FromBOTHWELL (1874)

From Act 1, scene 3

The Queen grants audience to John Knox.

From Act 1, scene 5

After the interview with Knox.

From Act 2, scene 1

Escape from Holyrood.

From Act 2, scene 6

At the Castle of Alloa.

From Act 2, scene 9

The Queen’s illness at Jedburgh.

From Act 2, scene 15

Bothwell meditates the murder of Darnley (I).

From Act 2, scene 18

Bothwell meditates the murder of Darnley (II).

From Act 3, scene 2

The Queen takes her leave of the murdered Darnley.

From Act 5, scene 2

The Queen incarcerated at Lochleven.

The Queen is presented with a bond to sign.

From Act 5, scene 4

The Queen’s conference with Murray, appointed Regent of Scotland.

From Act 5, scene 11

The Queen flees from the Battle of Langside.

From Act 5, scene 13

The Queen’s departure for England. At the shore of Solway Firth.

FromPOEMS AND BALLADS, SECOND SERIES (1878)

A Forsaken Garden

A Wasted Vigil

The Complaint of Lisa

Ave Atque Vale

A Ballad of Dreamland

Before Sunset

Triads

Translations from the French of Villon:

The Complaint of the Fair Armouress

Fragment on Death

Ballad against the Enemies of France

The Dispute of the Heart and the Body of François Villon

Epistle in form of a Ballad to his Friends

Epitaph in form of a Ballad

FromSTUDIES IN SONG (1880)

From By the North Sea

FromTRISTRAM OF LYONESSE (1882)

From Book 1

Iseult of Ireland aboard the Swallow, bound for Cornwall.

From Book 2

Iseult of Ireland is abducted by Sir Palamede and rescued by Sir Tristram.

From Book 3

Sir Tristram, exiled in Brittany, encounters Iseult of the Fair Hands.

Book 5

Iseult at Tintagel.

From Book 9

Tristram, dying in Brittany, sends Ganhardine to bring Iseult of Ireland from Cornwall.

FromA CENTURY OF ROUNDELS (1883)

The Way of the Wind

A Dialogue

Change

From Three Faces

FromA MIDSUMMER HOLIDAY AND OTHER POEMS (1884)

From A Midsummer Holiday

A Double Ballad of August

A Solitude

FromPOEMS AND BALLADS, THIRD SERIES (1889)

Night

In Time of Mourning

FromASTROPHEL AND OTHER POEMS (1894)

A Nympholept

From Loch Torridon

FromA CHANNEL PASSAGE AND OTHER POEMS (1904)

The Lake of Gaube

Roundel

Introductory Notes to the Longer Works

Explanatory Notes

Further Reading

Index of Titles and First Lines

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my editors at Carcanet for making this book a possibility, and then a reality. My greatest thanks go to Michael Schmidt, who suggested the idea, having known me only a short while, and then trusted me to get it right. Helen Tookey was my first managing editor for this edition, and Luke Allan, who later took over that role, has overseen the final transformation of my drafts into a book. They have been patient, sensitive and accommodating, and I thank them both very warmly.

I am also grateful to various friends with whom I have spoken about this project. Especially I recall conversations with Alison Hennegan, Robin Holloway and (a fellow enthusiast) Laura Kilbride. And many thanks are due to Arabella Milbank, who cheerfully and expeditiously supplied the translations from Swinburne’s invented French epigraphs.

Orla Polten has offered several pieces of advice that I should have been embarrassed to have gone without. I wish to give her my particular thanks, apologising, also, for having omitted ‘On the Cliffs’ (a favourite of hers).

Finally I would like to thank Sarah Green for her support and advice throughout the preparation of this book, and for her help in scrutinizing the proofs. Without her conversation, my introduction would have lacked a number of choice anecdotes and quotations.

If, in my introductory appreciations, I have taken some liberties such as scholars do not expect of one another, I hope to be forgiven much, quoniam dilexi multum. What is mine in this edition is dedicated to those friends who love Swinburne the most; and also, optimistically, to those who have hitherto liked him least. But it must also be dedicated to the Venerable Shade himself.

Introduction

ALGERNON CHARLES SWINBURNE was one of the most important poets of the nineteenth century. This is a point against which it would be hard to argue. But as one of the foremost poets of his century, he was also one of the most important poets in the whole of English literature; and for much of the last hundred years this judgement—this valuation of Swinburne not only as a major figure in his time, but as a great author of lasting significance—has met with much less broad consent.

Swinburne’s significance is permanent. He had a remarkable ear for the subtleties of poetic sound, and a phenomenal facility in composition. His technical skill was kept in motion by an impulse to innovate and surprise, both in matter and in form. As one old friend of his youth said at the time of his death, ‘Song was his natural voice’.1 It did not take long for the literary world to recognise what is perhaps insufficiently minded now, that Swinburne was one of the greatest writers of lyric in the history of the language. He was also one of the most controversial authors of the Victorian age—and in that guise he has been better remembered.

His music was very much his own. Even in the wake of Tennyson, who was praised for the delicate musical judgement of his verse, Swinburne immediately stood out as a special case. Though just as discerning in matters of melody and euphony, his effects drew more attention to themselves; they were bold and often dramatic in their semblance of spontaneity. They were more exaggerated. As an experimenter with many metrical forms, he was rivalled in ambition by other poets of the age—Clough before him, for instance, and Meredith alongside him, not to mention Tennyson himself. And in its changeful fluency and songlike modulation, Swinburne’s versification was at times very close to that of another great writer of lyric, Christina Rossetti, his friend. But his most characteristic effects were, in combination and certainly in sum, different from those of his peers: novel, emphatic, and yet at the same time persuasively ‘natural’ in movement. This musicality is more than a matter of sound alone: it has to do with the organization of the meanings of words; so that in Swinburne, to read the verse as it is designed to be read is to understand musically as well as to hear musically—more so, perhaps, than in any other poet of his age.

But his versification was not the only thing that made Swinburne a special case in the 1860s, when he first achieved fame. Since the late 1850s he had been part of the circle of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, drawing inspiration from his association with the likes of William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones and George Meredith, as well as all three of the literary Rossettis. But he had also been reading a range of French authors, including not only Victor Hugo, his lifelong hero, but also the most decadent of the moderns—Gautier, and, above all, Baudelaire. The ‘divine’ Marquis de Sade, too, found a place in Swinburne’s personal canon, despite the disappointment and boredom of his initial reading. In the 1866 Poems and Ballads, Swinburne blended the late-Romantic, medievalist sensuousness of the Rossetti circle (which was itself already voluptuous) with the more explicitly sexual, sado-masochistic themes that he found in his French authors. And so he became, among other things, the most important early ‘Decadent’ poet in English.

Many of the pieces included in the first Poems and Ballads were genuinely startling in their subversions and perversions. Friends and acquaintances advised him against publication of the most extreme, but Swinburne was not persuaded. Even a few months before publication, Meredith wrote to him:

As to the Poems—if they are not yet in the Press, do be careful of getting your reputation firmly grounded; for I have heard ‘low mutterings’ already from the Lion of British prudery; and I, who love your verse, would play savagely with a knife among the proofs for the sake of your fame.

When the time came, the advice having gone unheeded, he wrote to another friend:

Swinburne’s poems are out. Oh, bawdry! Oh, nakedness! Oh, naughtiness.

As Meredith predicted, and Swinburne must have expected, the Lion did roar. In The Saturday Review on 4 August, John Morley’s unsigned notice declared Swinburne ‘the libidinous laureate of a pack of satyres’, and—half-quoting the poem ‘Faustine’—decried his ‘nameless shameless abominations’. He also found the volume ‘silly’. On the same day, The Athenaeum ran an anonymous review by Robert Buchanan, who glanced back at the ‘considerable brilliance’ of Swinburne’s previous book, Atalanta in Calydon, before denouncing the new volume. Swinburne, in his view, was ‘deliberately and impertinently insincere as an artist’; he was ‘unclean for the mere sake of uncleanness’. Moxon, the publisher, flew into a panic and withdrew the book. The rights were transferred almost at once to John Camden Hotten, who knew a succès de scandale when he saw one.2

The stir was justified, because Swinburne’s transgressions were something truly new in main-stream English poetry. Poems such as ‘Fragoletta’, with its ambiguous sexuality, and ‘In the Orchard’, with its rather less ambiguous eroticism, were not as disturbing as those which, to many, really sounded like statements of wicked intent. In ‘Anactoria’ Swinburne had adopted the voice of Sappho, addressing a female beloved in terms of the most ferocious sado-masochistic eroticism, with some overt blasphemy adding yet more offence to conventional proprieties. In ‘Faustine’, the poet’s savage beloved is addressed as a reincarnation of the Empress Faustina, whose perverse bloodthirstiness is celebrated in similarly flamboyant terms. Most notorious of all was ‘Dolores’, a still more blasphemous song of praise to ‘Our Lady of Pain’. Its celebration of erotic torment was continued in other pieces, such as ‘Satia Te Sanguine’, while the antipathy to Christianity was taken further in the ‘Hymn to Proserpine’, ‘A Lamentation’, ‘Félise’, and many other pieces.

Antitheistic sentiment had also occasioned controversy in Swinburne’s previous book (and first success), the dramatic poem Atalanta in Calydon (1865). But in Poems and Ballads it could not be so easily excused, and began to emerge clearly as one of the author’s personal preoccupations. Time and again, he juxtaposed ‘pale’ Christian morality with the vibrant sensualism and ‘sin’ of the pagan world, and in so doing he played a major part in the initiation of an artistic tendency that lasted well into the next century. Even so, there were other times when, taking what Rossetti would call an ‘inner standing-point’ in his poems, Swinburne was able to enter convincingly into Christian feeling and imagination. ‘St Dorothy’ is the prime, but not the sole example in the 1866 collection; and in many of the later works this Christian empathy could stand alongside blasphemy, atheism and a general hostility to ecclesial religion.

With the 1866 Poems and Ballads, Swinburne was establishing a deliberately inflammatory poetic persona, which teasingly underlay the many of his poems that haunted the boundary between authorial utterance and dramatic monologue. Not every poem was equally extreme in flouting the moral conventions, but most were challenging and provocative in some other way. Even when least flagrantly decadent, his early poems were laden with the kind of bold sensualism that would a few years later get Rossetti into hot water.

But Decadence, except in its very worst manifestations, is never without some element of irony, and Swinburne’s verse is sophisticated in its ironic range. When he is most shocking, he is also at his most humorous; and much of his best work is characterised by a deft balancing of world-weary melancholy with mischievous wit. The masochistic instincts that motivate ‘Dolores’ were sincere; they emerge from authentic experince; but the extravagant images, scandalous flourishes and absurd rhymes are meant to provoke a smile as well as a saucy frisson. Even in his private correspondence, Swinburne delights in baroque fantasies of perversion (his flagellation fetish was very real); but when indulging his reveries in this vein he always has his tongue in his cheek, and feels the need to inform his confidants when he is once again talking ‘in my own person’. This, it must be insisted, does not diminish the authenticity of the feeling: his irony is not an abdication of the genuine. Almost always in Swinburne, as in the ‘Pre-Raphaelite’ verse of his friends Rossetti and Morris, there is an element of pastiche or parody—but ‘serious parody’, as Jerome McGann perceptively notes.3

The English Decadence that reached its zenith in the ’nineties would, no doubt, have happened anyway, with or without Swinburne’s example. But Swinburne helped to determine its course, and exercised an inelusible influence on the later poets, many of whom adopted aspects of his classicism, his medievalism, and the prosodic mannerisms of his stanzaic verse, even if in most cases they were not more, but rather less inflammatory in their own work. The combination of his novel poetic persona, with all its dark ambiguities of tone, and his novelties of form, with all those captivating cadences and compelling rhythms, not only made Poems and Ballads an immediate cause célèbre in the 1860s; it made Swinburne what he is—a major poet, sui generis, of enduring importance.

The press, of course, greeted the untoward matter of Swinburne’s most scandalous poems with general and strong disapprobation. But even some of the sternest critics were forced to concede that the young poet possessed a rare lyrical talent. Buchanan mounts his attack on the ‘prurient trash’ of Poems and Ballads in spite of ‘many pages of brilliant writing’; and Morley, who could find space in his review to talk of ‘sweet and picturesque lines’ and ‘passages of rare vigour’, was interested by ‘the music of his verse’, even though he found it immoderate and inconsistent with precise thinking. It says much that on 9 September 1866 John Ruskin, for all his moral sensitivity and gravity, wrote with confused feelings to Swinburne, who had sent him a copy of the volume,—

For the matter of it—I consent to much—I regret much—I blame or reject nothing. I should as soon think of finding fault with you as with a thundercloud or a nightshade blossom. All I can say of you, or them—is that God made you, and that you are very wonderful and beautiful.

Many friendly presences in Swinburne’s life felt, like Ruskin, that the power of his genius was great enough to pardon the vicious material, or at least to throw a veil of dumbstruck doubt over the whole matter. And like Ruskin, many felt that Swinburne’s genius ought to be turned to nobler ends; but not many of them saw any point in attempting to convince the poet himself.

After 1866, however, the nature of the shocks that Swinburne administered to the reading public was largely changed. Although the poet’s masochism continued to inform his poetry throughout his life, there would be no more poems like ‘Dolores’, ‘Faustine’ or ‘The Leper’. Poems of sexual perversion, calculated to astonish, gave way, on the whole, to poems of fiery, indignant republicanism and anti-clerical polemic. Even by 1871 (which saw the publication of Songs Before Sunrise, Swinburne’s first collection since 1866), the antitheistic vociferations of the earlier volume had been replaced by a more measured, considered, constructive metaphysical system, partly inspired by his studies of William Blake. ‘Hertha’ and ‘Genesis’, which are among the best poems of this period of Swinburne’s career, ceased to rail so noisily against the Christian God, and instead offered their own imaginative solutions; while the incendiary tirade ‘Before a Crucifix’, however deliberately offensive to Christian sensibilities, took its aim at the Church rather than the person of Christ himself. The Swinburnean sensuality remained, and continued to be richly provocative; but in later years—especially in the vivid erotic scenes in Tristram of Lyonesse—the frisson would come not so much from glaringly ‘strange’ sexualities and exquisite depravity, as simply from a commitment to be frank and graphic about sexual experience as, in his mind, it was or might be.

THE PERSONALITY

Almost everything about Swinburne encouraged people to treat him as an exception to the ordinary rules. Even his physical appearance was strange. Edmund Gosse describes it as ‘a kind of fairy look’.4 Others considered him variously boyish and girlish, and many found him ‘unearthly’. He was short, slight and pale, with sloping shoulders, delicate features and a weak chin. In youth, his large head was crowned by a luxuriant mass of long, dense, bright auburn hair. We read of his odd, ‘gliding’ walk; of how he had to cover one eye with his hand in order to read or write; of his amazing feats of memory, being able to recite interminably from the Greek dramas at the dinner table. Throughout his life, acquaintances remarked the incessant wavering and fluttering of his hands, and his legs seem to have jerked spasmodically when he was seated. In every way he seemed prodigious: he was the ideal genius. To some, he would become the paradigmatic degenerate artist.

Swinburne’s wild behaviour in the 1860s and 1870s was infamous. His life at this time took on a mythical quality for the gossips of literary London. Anecdotes collected around him, many of them canards. From 1862 to 1864 he shared with D. G. Rossetti the famous house at Cheyne Walk in Chelsea; William Michael Rossetti and George Meredith also had rooms, but were less often there. The goings-on at Cheyne Walk became legendary. The insomniac Rossetti stayed in bed till the afternoon, entertaining an array of artistic friends, and populating the premises with wombats, armadilloes and various other strange creatures—including several different kinds of owl, and a pomeranian. Some reports have Swinburne running around the house naked, and launching himself down the bannisters. At any rate, his drinking was getting out of hand. When sober, he was a model of formal politeness; when drunk, his comportment struck many as lunatic. Tempers at the Chelsea house seem to have been regularly lost: Meredith supposedly had milk thrown in his face by Rossetti when he called the latter a fool, and a poached egg pelted at him by Swinburne, in defence of Victor Hugo. Meredith voluntarily gave up his room, but in the end Rossetti had to ask Swinburne to leave.

The Cheyne Walk years thus came to an end in reality, though they would continue, ever after, to provide vivid matter for raconteurs, gossips and parodists. But Swinburne did not cease to give people things to talk about. His alcoholism became steadily worse, and fame after 1865 only fuelled his immoderate ways. Although there is probably some truth in Gosse’s claim (which at first sight seems incredible) that Swinburne ‘strove to avoid everything like affectation or eccentricity’,5 it seems clear that he enjoyed the notoriety; and he became, to some degree, a cultivator of canards.

A whole flock of canards was unleashed in 1868, when Swinburne almost drowned off the coast of Normandy while indulging his lifelong passion for the sea. By pure chance, it appears, a young man who would soon become one of the most important writers in France just happened to be walking along the shore at the critical moment. Swinburne was rescued by a fishing boat, but not before an eighteen-year-old Guy de Maupassant had supposedly set off to offer his own assistance. To show his gratitude, Swinburne invited Maupassant to lunch the next day at the rented cottage he was sharing with George Powell, one of his closest friends of the time, and the one most dedicated to decadent living and flagellatory fantasies. They must have enjoyed the visit, because the invitation was twice repeated.

Maupassant’s recollections of these three memorable lunches are found in three places, and the accounts are somewhat contradictory. The first version was preserved in the Goncourt Journal, and is supposed to be a transcript of the account Maupassant gave over dinner one evening in 1875, as the guest of Flaubert. In 1882 he told the tale again, in an article in Le Gaulois under the title L’Anglais d’Étretat; and from this version he later produced another, included in his introduction to the 1891 French translation of Poems and Ballads. He tells of strong spirits, which nearly sent him into a swoon; of copious collections of German homosexual pornography; of the flayed, severed hand of a parricide, which Swinburne used as a paperweight; and of a monkey, kept as a pet, which harassed the nervous visitor. Maupassant gradually discovers that Swinburne and Powell are sodomising their domestics, boys around fourteen or fifteen years old, as well as the monkey. On a later visit, the monkey has been hanged by a jealous servant, who is later chased out of the house by Powell, and possibly shot with a revolver. Maupassant declares his suspicion that the meat he had been given to eat, which he had initially mistaken for some kind of curious fish, was in fact monkey. He is, nevertheless, impressed by Swinburne’s conversation, and proclaims him pre-eminently ‘artistic’.

Similar stories continued to circulate, and the Goncourts’ dinner parties were at the centre of them. On one such occasion, Turgenev was present to witness an excited debate about the veracity of a story told, at second-hand, by the author Ludovic Halévy (co-author of the libretto for Bizet’s Carmen and several operettas by Offenbach). Halévy spoke about a young man he had once met, who claimed to have had an experience markedly similar to that described by Maupassant—but this time in the Isle of Wight, not Normandy.6 Swinburne (so the story goes) is living on the beach, in a tent, with no company besides a monkey dressed as a woman. The monkey is both lover and servant. When the young man arrives, Swinburne attempts to seduce him, meanwhile whipping the monkey, who, in a fit of jealousy, attacks the visitor with murderous intent. On a subsequent visit, Swinburne—now waited on by an Irish butler—serves up the monkey to the young man for lunch. More likely it was canard à la presse, for the story sounds like the purest quintessence of canard. But one cannot dismiss the suspicion that Swinburne and Powell had deliberately set such stories in motion in the first place, by having given the young Maupassant a show to remember.

Swinburne’s sexuality was a subject of inexhaustible rumour, and remains a subject of speculation. His emotional life was indelibly marked by an intense early attachment to a cousin, Mary Gordon, whose marriage to another badly affected him. The failure of this love, which never seems to have been supplanted, is now generally thought to have been the inspiration for ‘The Triumph of Time’, and many other poems of romantic disappointment. His sexual instincts were closely involved with his obsession with flogging, an interest dating to his school days at Eton, and which continued to be homosocial in expression (verbally), if not necessarily in commission. He often liked to skirt around the topic of male homosexuality, and female homosexuality was a recurrent theme in his work; but there is no plain evidence of his engaging in homosexual encounters, and even the evidence for full heterosexual encounters is slight only. His professed horror of sodomy, and the ostensibly sincere distaste with which he reacted to the disgrace of his erstwhile friend, the painter Simeon Solomon, when the latter was convicted of such acts, might well seem to indicate that Swinburne was, at any rate, in no usual sense homosexual.

Perhaps he was not anything in the ‘usual’ sense. In the 1860s and early 1870s he regularly visited a specialist brothel in St John’s Wood where he was whipped by a couple of young ladies. It seems that the flagellation was not reciprocated, and it is not quite clear whether Swinburne also indulged in the activities for which ordinary brothels are chiefly used. His only known love-affair was a six-month fling with the controversial American actress and amateur poet Adah Menken, in 1867–68; and it was said that Swinburne’s friends (variously Rossetti, Richard Burton and, oddest of all, the Italian Risorgimento activist Giuseppe Mazzini) had set up the whole business, worried that Swinburne needed a woman’s influence, or that the thirty-year-old poet, in spite of his dealings with the whipping-girls, was inexperienced. But all of these biographical anecdotes tell us less—and less important things—than the poems themselves. What is important is that we should remember that Swinburne’s sexual interests were no merely fashionable caprices, but profoundly involved with the whole of his emotional life; and these erotic emotions can only have been very imperfectly answered in St John’s Wood. Above all, they were also involved with the other great focus of his thought and feeling, the realm of poetry; and they found their answers, their correlatives, it would seem, in an intense fusion with the aesthetic.

It is usual to think of Swinburne’s biography as a story in two volumes. The person who exercised the most profound and lasting influence over the later period of his life was the author of Aylwin, Theodore Watts-Dunton. ‘Watts’ appeared in Swinburne’s life in 1872. E. F. Benson tells an amusing anecdote of that first appearance, typical of the kind of thing that was often said about meetings with the poet. Watts had been given by his friend Rossetti a letter of introduction, and went to see Swinburne at home. He knocked to no avail, and let himself into an empty living room. Hearing noise from another room, he knocked again without success, and opened the door;—

He found Swinburne stark naked with his aureole of red hair flying round his head, performing a Dionysiac dance, all by himself in front of a large looking glass. Swinburne perceived the intruder, he rushed at him, and before Mr. Watts-Dunton could offer any explanation or deliver his letter of introduction, he was flying in panic helter-skelter down the stairs …7

Unfortunately, there is no reason to believe a word of Benson’s delightful relation; but tales of Swinburne’s startling nudity were not uncommon, and perhaps there is no smoke without fire. George Moore claimed to have visited Swinburne in the 1870s, with a letter of introduction from W. M. Rossetti. Mounting to the first floor of the building in which the poet was resident, he opened a door which did not seem likely to lead directly to private lodgings, and found an empty room containing only a truckle bed:

Outside the sheets lay a naked man, a strange impish little body it was […]. How I knew it to be Swinburne I cannot tell. I felt that there could be nobody but Swinburne who would look like that.8

The young Moore was shocked, made excuses, and left. Perhaps neither story is true; it is unlikely that Moore could be have been ignorant of Swinburne’s personal appearance at that time.

Moore, in any case, never encountered Swinburne again, but Watts became a fast friend. At the end of the decade he would become a guardian as well as a friend, and under his care scenes of this nature would be far less likely.

In the year following the publication of a second series of Poems and Ballads (1878), a collection that included such important poems as ‘Ave atque Vale’ and ‘A Forsaken Garden’, Swinburne’s fragile health became worse than ever before. His alcoholism and erratic lifestyle were almost certainly to blame. Only in his early forties, he was effectively an invalid, almost completely deaf, bedridden and unable to work. Watts was alarmed, and took Swinburne in a cab from his lodgings in Guildford Street to an address in Putney, on the outskirts of London, where Watts lived with a sister. A recovery followed, and after a brief stay with his family at Holmwood, Henley-on-Thames, Swinburne agreed to move in with Watts on a more permanent basis. So began the years at number 2, The Pines, Putney, where Swinburne lived under the solicitous care of Watts for the rest of his life—thirty years, from 1879 to 1909.

In his first few years at The Pines, Swinburne completed and published his Arthurian epyllion Tristram of Lyonesse, which is among his most significant literary achievements. But as the years passed, though still prolific, Swinburne produced less and less good poetry. There is plenty of it, certainly, and the best—some of it truly remarkable—is included in this selection. It was outweighed, however, by reams of verse praising canonical English authors, or (unlikely as it may seem) celebrating the loveliness of babies. His Sonnets on English Dramatic Poets are almost as dull as they sound; but the bland, sincere sentimentality of the baby poems, though pleasingly humane at root, is ghastly to anyone who cares about Swinburne’s poetic genius. It was an emotion which, however deeply felt, he was not able to convert into art objects worthy of himself.

‘Next to love of his friends came Swinburne’s love of the sea’, wrote Clara Watts-Dunton—Theodore’s widow—in a cosy book called The Home Life of Algernon Charles Swinburne. ‘And next to his love of the sea ranked his love of babies’.9 Swinburne spent mornings, in these later years, walking in Putney and Wimbledon, and he earned a reputation for admiring infants in passing perambulators. One of these was a very small Robert Graves, who later, in the second paragraph of Goodbye to All That (London, 1929), called Swinburne ‘an inveterate pram-stopper and patter and kisser’. Graves claimed to remember him, presumably from days long after the pram had been left behind, as a botherer of mothers and children: ‘I did not know that Swinburne was a poet, but I knew that he was a public menace’. To go by more reliable accounts, however, the Bard was positively encouraged in this peculiar devotion by ‘fond parents’, who, in Clara Watts-Dunton’s words, ‘literally pelted the poet with photographs of their respective offspring’.10

Now bearded and bald, and somewhat more stocky, Swinburne had achieved (or arrived at) a kind of respectability. The change from bohemian hell-raiser to the doddering suburban ward of Watts struck many as humorous, while for others it was a cautionary tale, and cause for regret. ‘In my youth’, wrote Max Beerbohm after Swinburne’s death, ‘the suburbs were rather looked down on—I never quite knew why. It was held anomalous, and a matter for merriment, that Swinburne lived in one of them’.11 Even in suburban Putney, he continued to be a mythical figure, an old institution in the literary world, paid visits by younger writers. There was a general feeling that Watts was too controlling of the great poet, too jealous a keeper; and this side of the story was given greater emphasis after both men were in their graves. Clara Watts-Dunton, years later, addressed such grumblings and sniggers:

I have never understood, and never expect to understand, the motive actuating those persons who, after the deaths of Swinburne and Watts-Dunton, began to belittle the famous friends. To me their intimacy is simple and beautiful.

Her defence is quite moving, both rationally and emotionally. To her, ‘the Author of “Atalanta” was just a human being who wanted to be loved and taken care of’.12

But the domestic situation was bound to seem odd, and a little ridiculous. Watts had almost certainly saved the life of his celebrated friend, but he had also captured and domesticated a Wild Poet. ‘In the suburbs’, G. K. Chesterton remembered, ‘Swinburne was established as Sultan and Prophet of Putney, with Watts-Dunton as a Grand Vizier’.13 George Moore, even in the poet’s lifetime, pointedly remarked that Swinburne—

when he dodged around London, a lively young dog, wrote ‘Poems and Ballads’ and ‘Chastelard’; since he has gone to live at Putney, he has contributed to the Nineteenth Century and published an interesting little volume entitled, ‘A Century of Roundels’, in which he continued his plaint about his mother the sea.14

For Moore, Swinburne’s art had been spoiled by his suburban neutralization, but for others the decadence of the earlier Swinburne was still a danger, even though the poet himself was living in calm retirement. As late as 1895, the protagonist of Marie Corelli’s best-selling novel The Sorrows of Satan can be heard vehemently decrying the viciousness of Swinburne’s work of two or three decades earlier:

At first I read the poems quickly, with a certain pleasure in the mere swing and jangle of rhythm, and without paying much attention to the subject-matter of the verse, but presently, as though a lurid blaze of lightning had stripped a fair tree of its adoring leaves, my senses suddenly perceived the cruelty and fiendish sensuality concealed under the ornate language and persuasive rhymes […]. I concluded that Swinburne must, after all, be right in his opinions, and I followed the lazy and unthinking course of social movement, spending my days with such literature as stored my brain with a complete knowledge of things evil and pernicious.15

In one sense, Swinburne would forever be the poet he had been in the ’sixties and ’seventies. In another, his later work and his more mature existence would always be held up against the lingering myth of those earlier days. To Beerbohm, who must have spoken for many, ‘the essential Swinburne was still the earliest. He was and would always be the flammiferous boy of the dim past’.16

THE PROSODIC GENIUS

No introduction to Swinburne, however brief, could do without an appreciation of his formal achievements. In all poetry, form is vital; but this is rarely, if ever, more true than it is in Swinburne. It is not that the form is everything and the content nothing, but rather that in Swinburne this troublesome but indispensible division is especially hard to make. Accounts of Swinburne that stress merely the scandalous subjects of the famous poems are always unsatisfactory, because to be scandalous is a pretty facile thing, and Swinburne is rarely facile. Similarly, the kind of critique that happily dismisses the subject and, however admiringly, looks at Swinburne as a musical arranger of words and nothing more, is just as regrettable. There is real thought, feeling and drama, real structure and subtlety in Swinburne’s ‘matter’, so to speak. It cannot be stressed enough: the subject is therefore far from nothing. But it would be close to nothing without the form, if such a thing could be imagined. Swinburne does not translate well.

To sympathetic readers of his own age, Swinburne was above all a versifier of peculiar technical power—which meant, for the reader, aesthetic power. To say he was a brilliant or consummate prosodist is not enough, because it does not sufficiently convey this peculiarity. The following observations are intended to introduce a few aspects of Swinburne’s prosodic style, and to communicate as well as I am able something of the pleasure of his effects.

Swinburne distinguished himself partly by the freedom with which he made prosodic substitutions, allowing the rhythms to alter and slide and trip, without violating the sense of the metrical limits or the repeating structures which, in him, they always entail. He was a master of many kinds of modern English metre, an experimenter with classical metres, and the inventor of stanzas and cadences that lingered in the minds of poets and readers for decades, and perhaps still do. He became known for his habitual use of careering anapaests—both in long lines and in well-tempered stanzas—and for the mixed metres and metrical inversions that give the sense of the galloping anapaest even where scansion reveals only disyllabic feet. Much of his most characteristic verse has a compelling rhythmic sweep, a sense of fluency enlivened by irregularities. The ‘Hymn to Proserpine’ illustrates his early use of long lines with a strongly anapaestic rhythm:

All delicate days and pleasant, all spirits and sorrows are cast

Far out with the foam of the present that sweeps to the surf of the past:

Where beyond the extreme sea-wall, and between the remote sea-gates,

Waste water washes, and tall ships founder, and deep death waits.

The melodic motions are produced by careful co-ordination of the internal rhymes, the caesurae, the surges of the rhythm and the lavish alliterations,—all working together and pulling against each other. His control of the rhythm is sure, and the principle is musical variety, achieved through enjambment and the manipulation of syntax. In the second of these two couplets, for instance, he deftly interrupts the more ordinary movement of the foregoing: first, by over-emphasising the caesura (line 3); and then by compensating for this in the next line with a strongly tripartite division of the syntax, which effectively overrides the central pause (line 4). Swinburne continued throughout his life to experiment with expansive anapaestic lines, and the habit culminated in his last great poem, ‘The Lake of Gaube’.

Even more sophisticated results were attained in stanzas where the feet are mixed, apparently in caprice—but where the caprice is really an unfailing intuition for the music of the whole strophic arrangement. As in the final line of the passage quoted above, Swinburne often made skillful use of clustered stresses:

Waste water washes, and tall ships founder, and deep death waits.

Although not all are of equal weight, there are, from a strictly metrical point of view, far too many stresses called for in this line. It is fundamentally a line of six feet, or six beats; but any sensitive reading will register more stresses than six. One has to place stress on ‘waste’, ‘ships’ and ‘death’. It does little good to talk of spondees; these effects are not usefully described in terms of ‘feet’, for they are really just instinctive substitutions of emphasis which pile up over the top of the established metrical structures. This technique of clustering stresses was brilliantly incorporated into the stanzas of some of Swinburne’s most famous poems, including ‘A Forsaken Garden’ (included here); but the first and best example of the particular stanzaic choreography of these effects was one of his very greatest poems, ‘The Triumph of Time’:

Before our lives divide for ever,

While time is with us and hands are free,

(Time, swift to fasten and swift to sever

Hand from hand, as we stand by the sea)

I will say no word that a man might say

Whose whole life’s love goes down in a day;

For this could never have been; and never,

Though the gods and the years relent, shall be.

Is it worth a tear, is it worth an hour,

To think of things that are well outworn?

Of fruitless husk and fugitive flower,

The dream foregone and the deed forborne?

Though joy be done with and grief be vain,

Time shall not sever us wholly in twain;

Earth is not spoilt for a single shower;

But the rain has ruined the ungrown corn.

The ponderous accumulation of stresses—not a clotting but rather a kind of throbbing or thudding—occurs at moments of emotional intensity, and these are musically orchestrated. You need at least four strong stresses in the phrase ‘Whose whole life’s love goes down’, though ordinarily there would only be three, which is the number of metrical beats in the phrase; and it is hard to avoid stress (or prosodic ‘length’) in the second syllable of the word ‘ungrown’, while the metre calls for an accent upon the first. The stanza pads sadly to a halt in that slow, bitter, heavy phrase with its internal half-rhymes: ‘the úngrówn córn’. Meanwhile, the shifts between basically iambic and basically anapaestic rhythms are beautifully combined with the shifts in the feeling and with the adjustments of all the variables, including the assonance which is so pronounced here. The speed of recital, too, is directed with wonderful sensitivity, and prosodic awkwardness is brilliantly used: look at the poignant rubato effect called for at the start of the third line. The essential style of this versification is based on inconsistency, the variations of slowing and quickening, taken just as far as they can go within the elastic bounds of a regularity of melody which is aesthetically unmissable and unloseable. Each stanza of the poem is a slightly different variation on the same melodic shape, plain enough to govern even the pitch and modulation of the voice. Swinburne believed that ‘genuine lyric verse’ determined for the reader its own proper ‘singing notes’.17

Almost all of these idiosyncrasies were present also in Swinburne’s heroic couplets, which were deliberately unconventional in motion and texture. Tristram of Lyonesse was his greatest work in this form, and contains passages of a lyrical velocity unmatched in kind by the same metre in any other hands. He made enjambment a matter of the utmost drama and suspense, driving forward the long climactic periods through ever-changing cadences:

And as the august great blossom of the dawn

Burst, and the full sun scarce from sea withdrawn

Seemed on the fiery water a flower afloat,

So as a fire the mighty morning smote

Throughout her, and incensed with the influent hour

Her whole soul’s one great mystical red flower

Burst, and the bud of her sweet spirit broke

Rose-fashion, and the strong spring at a stroke

Thrilled, and was cloven, and from the full sheath came

The whole rose of the woman red as flame …

The emphasis here is mine. A series of small, connected peaks of sensuous emotion is built by the boldness with which the poet tips the most thrilling verbs—each one monosyllabic and long—over the line-break: ‘burst’ and ‘thrilled’. Counterpoint is provided by the answering verbs, also monosyllabic, which reside in the normal seat of semantic emphasis, the end of the line: ‘smote’, ‘broke’, ‘came’. And in this passage is found possibly the most extreme example of Swinburne’s accentual agglomerations: ‘Her whole soul’s one great mystical red flower’. It is amazing that a line which conveys a sense of such powerful momentum should be so very impossible to read at speed.

The lilting lyrics in slenderer stanzas, typified by ‘The Garden of Proserpine’, ‘Ilicet’, ‘Before Dawn’ and ‘A Match’, are another thing again. Metres of this kind were among those most widely and successfully imitated by the lyrical poets of the 1880s and 1890s. In was in such poems that Swinburne, whose tendency was always toward song, was closest to the traditional forms of song; and his prosodic debt in this regard to Christina Rossetti—with whom, despite significant variance of temperament and opinion, he had a warm friendship—is not often enough acknowledged.18 Both were among the poets of the 1860s most smooth and melodic in lyrical versification. In general, Swinburne’s songlike stanzaic poems show the influence of Tennyson, as well as Shelley, his natural predecessor in this respect. But the languid evolutions and repetitions of the syntax; the lavish investment in pattern and melody, and local sense even at the expense, sometimes, of total sense—building up meaning by variation as much as by successive argument: these characteristics made Swinburne’s poems something new.

Yet Swinburne’s best verse is not always so fluid in motion. Some of his greatest poems, especially in the first collection of Poems and Ballads (1866)—poems such as ‘Laus Veneris’, ‘The Leper’, ‘Faustine’ and ‘After Death’—are characterised by a quite different prosodic manner, just as musical, if less obviously songlike. In such poems, Swinburne adapted the Pre-Raphaelite style of D. G. Rossetti’s earlier poems and William Morris’s Defence of Guenevere: a style in which certain kinds of awkwardness—in syntax, metre and rhyme—were deliberately cultivated, and integrated with a highly stylized archaism. The broken, spoken rhythms of Robert Browning were combined with a lyrical primitivism, always in search of the little touches that made old verse so pleasingly strange to modern ears. Swinburne took this approach from Rossetti and Morris, together with their Keatsian sumptuousness, and added to it the stamps of his own poetic voice. One of the most obvious features of this manner, a feature shared particularly with Rossetti, is the unnatural tilting of the spoken emphasis in rhyme-words. The example which comes to mind is the first stanza of ‘The Leper’, which asks us to rhyme ‘her’ with ‘well-water’. This is not a half-rhyme, of the kind we are used to from twentieth-century poets: it actually wrests the accent—not wholly, but appreciably—towards the second syllable of ‘water’, giving an effect that delights through calculated archaistic gawkiness. Even to the deliberately crabbed or angular metres of poems such as these, where ‘natural’ fluency is stemmed and redirected in various ways, Swinburne brings a continually varying music, shot through with the weird pungency of tactfully twisted syntax, the excitement of alterations in the regulated pacing, and the sharpness of his ‘alliterative thunderbolts’.19

SWINBURNE’S LEGACY

Swinburne was a poet who needed to be dealt with. Watts-Dunton had to take him in hand for his own well-being; but the reading public and the literary world, too, had just as much trouble in responding to Swinburne’s marvellous precedents—taking him to task, assimilating him, trying to place him suitably within the culture of the age. The succeeding age—the time of ascendant Modernism and the ‘New Criticism’—was forced to deal with him over again, and did so with such efficacy that his reputation at large has never quite recovered. Critics are still trying to deal with him, and his challenge remains vigorous and vital. But the challenge does not arise merely from his being shocking, in any common sense. It comes, most of all, from his being so aesthetically compelling in a manner so different from any other poet—even his own imitators.

Admirers of Swinburne’s poetry know that its pleasures are extraordinary. But Swinburne today does not have as many admirers as he deserves. Part of the problem is that what his admirers take for his most essential merits, detractors have found grotesque or annoying. He is an extreme case. Not every reader can enjoy Swinburne, but it is necessary to acknowledge the fact that, in reality, the very same characteristics that seem irresistibly appealing to some are those that are dismissed as repugnant or ridiculous by those who do, intuitively, resist; and that, as literary history has transpired over the past century, it is the latter class of reader which has had the more decisive and enduring impact upon Swinburne’s critical fortunes.

Swinburne has never really gone away; he is certainly not forgotten, and the controversy he occasioned in the ’sixties and ’seventies has kept him firmly in the background (at least) of Victorian culture, as an anecdotal presence. But some canonical authors can be little read—and even less frequently read for pleasure—without being in danger of losing canonical status. Swinburne is one of these. Among those who know something about him, the majority know Swinburne either as a decadent curiosity or as a scapegoat of the Modernists and New Critics—an emblem of the type of thing that the generation of Eliot and Pound supposedly disliked. It was entirely necessary for that generation to confront and overcome, for their own practice, the legacy of Swinburne; and it was right for them to do so. In truth, however, both Eliot and Pound were more moderate in their criticisms than many of their followers in the later twentieth century have been inclined to believe; and, in any case, we should no longer feel bound to observe the sides taken in a debate that is now so distant.

The younger Pound, like Yeats, was much influenced by the late-Victorian aestheticism in which Swinburne had taken a major role, and throughout his career Pound retained his interest in the literary scene on the other side of the fin de siècle. Swinburne turns up all over his work, a personality taken for granted, thriving in the Poundian world of cultural anecdotalism. Pound took palpable pleasure, for example, in repeating the story of George Moore’s supposed encounter. But the poetry, too, is taken for granted. ‘To quote his magnificant passages is but to point out familiar things in our landscape’. This is Pound in 1918, writing in defence of Swinburne against the banality (as he saw it) of Gosse’s recently published biography. There remains a persistent idea that Pound hated all things Victorian, which is nonsense; and he had a place for Swinburne, so long as it was not the anodyne, respectable place being carved out for him by Victorian survivors like Gosse. Pound could not stomach the notion of a Swinburne ‘coated with veneer of British officialdom and decked out for a psalm-singing audience’.20

Among the mixed praise and blame of that essay, Pound in 1918 remarked that ‘Swinburne’s art is out of fashion’.21 It was Eliot who intervened most decisively in the history of Swinburne’s reputation when, two years later, he published the essay ‘Swinburne as Poet’;22 and even Eliot is suitably respectful to Swinburne’s ‘genius’. He takes the work seriously, and judges it not to be ‘fraudulent’. But he feels able to say with confidence, entering the third decade of the twentieth century: ‘we do not greatly enjoy Swinburne’.

One of the most important things to note about this statement is that it is firmly rooted in a specific moment. For although Eliot expects his reader to agree that ‘we do not greatly enjoy Swinburne’, it is also agreed that ‘at one period in our lives we did enjoy him and now no longer enjoy him’. He talks of Swinburne as he talks of Rossetti elsewhere: a case of ‘rapture’ followed by ‘revolt’.23 Both poets are relegated to the realm of adolescent thrills, soon outgrown; but it is also a matter of literary history and the supposed shift in sensibility experienced by the whole generation.

Eliot’s main objection is that Swinburne is ‘diffuse’, though he sensibly points out the difficulty of criticism in this matter, when he acknowledges that Swinburne’s diffuseness ‘is one of his glories’. It is clear to Eliot that the debate is to be between those who enjoy Swinburne’s characteristics and those who do not; that the characteristics are the same whether taken for merits or faults. Swinburne is ‘diffuse’ because he is ‘general’ where, in Eliot’s view, he ought to be specific, concrete. The essay relies on a basic distinction between words and objects, and an assumption about their ideal relationship in poetry. For Eliot, words are there to point to meanings in the world of objects, and should be identified as fully as possible with those objects. In Swinburne, he says, ‘the object has ceased to exist’. The word becomes divorced from the world, even from the world of interior feeling;—‘It is, in fact, the word that gives him the thrill’. This seems to him insufficient, or at least a mistake of priorities.

A third element in poetic language is music, or sound; but owing to the peculiar way in which Eliot chooses to use the word ‘music’, he is able to declare, against tradition, that Swinburne is not in fact really musical at all: ‘the beauty or effect of sound is neither that of music nor of poetry which can be set to music’. He is probably right on the latter count, though it is not clear why this should be relevant. In Campion, by contrast (and presumably Campion is chosen as an example precisely because he was a musical setter of his own lyrics), ‘musical value’ and ‘meaning’ are two distinct things, put together; but in Swinburne ‘the meaning and the sound are one thing’, and the result is just a muddle. Eliot appears to regard the ‘music’ of verse, which he considers an essential component, as something more or less extrinsic to both the ‘images’ and the ‘ideas’; the more closely all these things are fused at their birth, the less happy he is. It is important to realise that Eliot’s presuppositions in this matter are rather unusual, and there is no good reason why we should continue to apply them to Swinburne, whose stylistic achievement is much better construed by reference to the famous pronouncement of his contemporary, Walter Pater, that ‘All art constantly aspires to the condition of music’:—

lyrical poetry, precisely because in it we are least able to detach the matter from the form, without a deduction of something from that matter itself, is, at least artistically, the highest and most complete form of poetry.

[T]he ideal examples of poetry [are] those in which […] form and matter, in their union or identity, present one single effect to the ‘imaginative reason’.24

Pater shows us not only how Eliot’s analysis might be countered by the use of a different, more appropriate conceptual frame, but also what Eliot himself was strenuously reacting against. He is in no way blameable in this, but it is unfortunate that his judgement has caused so much hindrance to the appreciation of Swinburne over the past hundred years.

Looking at the matter very rationally (which may be, in some ways, inappropriate), it is less than entirely clear why Eliot should object so strongly in Swinburne to the dissociation of ‘words’ from ‘life’, when elsewhere he expresses the conviction that poetry is a medium ‘in which impressions and experiences combine in peculiar and unexpected ways’, and that the poet should, by mingling and manipulating the emotions of real life, ‘express feelings which are not in actual emotions at all’.25 That seems a pretty fair description of what Swinburne does, in the poems to which people most often object. He creates a wholly peculiar literary experience, with its own literary emotions—related to ‘actual’ experience and emotions, certainly (if not always to ‘reality’ in the mundane sense, then to the reality of fantasy); but nevertheless created. That world is persuasively consistent, and quite unique; the feelings it describes are closely identified with the aesthetic feelings they call out and, in turn, rely upon for conveyance. If one kind of experience, ‘real life’, seems less than usually solid in his work, it is because the work itself is its own experience, just as the literary works which inspired Swinburne count as ‘experience’ every bit as much as any other part of his life.

‘Only a man of genius’, Eliot does not grudge to admit (and without undue excess of irony), ‘could dwell so exclusively and consistently among words as Swinburne’. It would be hard to disagree. Eliot did not set out to demolish Swinburne, whom he regarded as ‘indestructible’, and his condemnation is both measured and frankly grounded on taste. In the 1970s, the poet Veronica Forrest-Thomson wrote a detailed refutation, carefully scrutinizing Swinburne’s putative ‘diffuseness’, and using the observations in Eliot’s essay as starting points for ‘a positive analysis’.26 But it seems that she is in rather a small minority of readers since 1920 who are willing to see in Eliot the foundation for an appreciative response to Swinburne.

Forrest-Thomson’s championship betokens a larger tendency. Insipid as it may be to say so, Swinburne is something of a ‘poet’s poet’, as well as a poet’s bête noire. For those invested in matters of poetic form, style, technique, he is the kind of figure who rouses strong feelings one way or the other. If you want to see clearly the traces of Swinburne in the work of appreciative modern poets, Wallace Stevens is a good place to begin, or George Barker. For example, read Barker’s poem ‘At Thurgarton Church’ (1971) after Swinburne’s ‘By the North Sea’: the mood and manner are strikingly alike, though the measure is different; and some stanzas could almost be Swinburne, though Barker deliberately roughens, sharpens and interrupts the familiar cadences he evokes. As for Stevens, his poem ‘To the One of Fictive Music’, from Harmonium (1923), may well be the most Swinburnean thing in the whole Modernist repertoire.27 Or else, after immersion in Swinburne’s ‘Faustine’, ‘Félise’ and ‘Before the Mirror’, look at another poem from Harmonium, the ‘Apostrophe to Vincentine’, and it seems almost a pastiche—the regular rhythms and rhymes, which recall the Swinburnean style, broken into irregular lines, and then playfully varied in a way suggesting the bobbed final lines of the ‘Dolores’ stanza. It is not even that the underlying rhythms are intrinsically or specifically Swinburnean: it is a matter of the sensuous particularities of the words themselves in their repetitions and echoes and aesthetic evocations, the diction and its sounds married to the rhythm, and to the subject, in this particular way. And it is a matter of tone, an essential part of this ‘working’ of words. Modernistic as it is, the ludic, half-parodic ‘Apostrophe to Vincentine’ is closer to Swinburne, in a profounder way, than any of Stevens’ more overtly Victorian juvenilia.

These poems by Barker and Stevens are offered simply as obvious examples, where the presence is palpable, and probably meant to be. But in each of these poets and many more, a less easily identifiable legacy of Swinburne’s formal experimentation surely takes some part, even if only in the most abstract, or theoretical, or wholly unconscious way. And the surface features of his poetry, its texture, which had such an impact on the verse of the last three decades of the nineteenth century—including that of Hardy and Yeats, who mediated the influence for later poets,—lingered, sure enough, among even the most reluctant of inheritors. It has often been argued that Eliot’s poetry bears Swinburnean impressions, presumably despite the author’s intentions. This is the price he pays for protestation.

Many other major critics have been inclined to take a view similar to that articulated by Eliot. Leavis thought that Swinburne demanded ‘a suspension, in the reader, of the critical intelligence’. The very inevitability of Swinburne’s prosody, its ‘tripping onrush’, simply ‘rushes us by all questions’, but closer examination reveals imprecision of thought and illogicality of image.28 And Leavis is partly