2,99 €

2,99 €

oder

-100%

Sammeln Sie Punkte in unserem Gutscheinprogramm und kaufen Sie E-Books und Hörbücher mit bis zu 100% Rabatt.

Mehr erfahren.

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

"I entered literary life as a meteor, and I shall leave it like a thunderbolt." These words of Maupassant to Jose Maria de Heredia on the occasion of a memorable meeting are, in spite of their morbid solemnity, not an inexact summing up of the brief career during which, for ten years, the writer, by turns undaunted and sorrowful, with the fertility of a master hand produced poetry, novels, romances and travels, only to sink prematurely into the abyss of madness and death. . . . .

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

0,0

Bewertungen werden von Nutzern von Legimi sowie anderen Partner-Webseiten vergeben.

Legimi prüft nicht, ob Rezensionen von Nutzern stammen, die den betreffenden Titel tatsächlich gekauft oder gelesen/gehört haben. Wir entfernen aber gefälschte Rezensionen.

Ähnliche

Short Stories of Guy de Maupassant

Short Stories of Guy de MaupassantIntroductionTWO FRIENDSTHE LANCER'S WIFETHE PRISONERSTWO LITTLE SOLDIERSA COUP D'ETATTHE HORRIBLEA DUELEPIPHANYTHE MUSTACHETHE QUESTION OF LATINTHE BLIND MANA FAMILY AFFAIRBESIDE SCHOPENHAUER'S CORPSETHE DISPENSER OF HOLY WATERTHE DOORTHE IMPOLITE SEXTHE MORIBUNDTHE WRONG HOUSEFAREWELL!THE WOLFTOMBSTONESCLAIR DE LUNEUSELESS BEAUTYA TRESS OF HAIRMOONLIGHTTHE FIRST SNOWFALLSUNDAYS OF A BOURGEOISTHE EFFEMINATESTHE DEVILTHE DIARY OF A MADMANTHE MASKCopyrightShort Stories of Guy de Maupassant

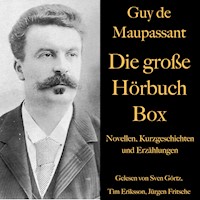

Guy de Maupassant

Introduction

"I entered literary life as a meteor, and I shall leave it like a

thunderbolt." These words of Maupassant to Jose Maria de Heredia on

the occasion of a memorable meeting are, in spite of their morbid

solemnity, not an inexact summing up of the brief career during

which, for ten years, the writer, by turns undaunted and sorrowful,

with the fertility of a master hand produced poetry, novels,

romances and travels, only to sink prematurely into the abyss of

madness and death. . . . .

In the month of April, 1880, an article appeared in the "Le

Gaulois" announcing the publication of the Soirees de Medan. It was

signed by a name as yet unknown: Guy de Maupassant. After a

juvenile diatribe against romanticism and a passionate attack on

languorous literature, the writer extolled the study of real life,

and announced the publication of the new work. It was picturesque

and charming. In the quiet of evening, on an island, in the Seine,

beneath poplars instead of the Neapolitan cypresses dear to the

friends of Boccaccio, amid the continuous murmur of the valley, and

no longer to the sound of the Pyrennean streams that murmured a

faint accompaniment to the tales of Marguerite's cavaliers, the

master and his disciples took turns in narrating some striking or

pathetic episode of the war. And the issue, in collaboration, of

these tales in one volume, in which the master jostled elbows with

his pupils, took on the appearance of a manifesto, the tone of a

challenge, or the utterance of a creed.

In fact, however, the beginnings had been much more simple, and

they had confined themselves, beneath the trees of Medan, to

deciding on a general title for the work. Zola had contributed the

manuscript of the "Attaque du Moulin," and it was at Maupassant's

house that the five young men gave in their contributions. Each one

read his story, Maupassant being the last. When he had finished

Boule de Suif, with a spontaneous impulse, with an emotion they

never forgot, filled with enthusiasm at this revelation, they all

rose and, without superfluous words, acclaimed him as a

master.

He undertook to write the article for the Gaulois and, in

cooperation with his friends, he worded it in the terms with which

we are familiar, amplifying and embellishing it, yielding to an

inborn taste for mystification which his youth rendered excusable.

The essential point, he said, is to "unmoor" criticism.

It was unmoored. The following day Wolff wrote a polemical

dissertation in the Figaro and carried away his colleagues. The

volume was a brilliant success, thanks to Boule de Suif. Despite

the novelty, the honesty of effort, on the part of all, no mention

was made of the other stories. Relegated to the second rank, they

passed without notice. From his first battle, Maupassant was master

of the field in literature.

At once the entire press took him up and said what was appropriate

regarding the budding celebrity. Biographers and reporters sought

information concerning his life. As it was very simple and

perfectly straightforward, they resorted to invention. And thus it

is that at the present day Maupassant appears to us like one of

those ancient heroes whose origin and death are veiled in

mystery.

I will not dwell on Guy de Maupassant's younger days. His

relatives, his old friends, he himself, here and there in his

works, have furnished us in their letters enough valuable

revelations and touching remembrances of the years preceding his

literary debut. His worthy biographer, H. Edouard Maynial, after

collecting intelligently all the writings, condensing and comparing

them, has been able to give us some definite information regarding

that early period.

I will simply recall that he was born on the 5th of August, 1850,

near Dieppe, in the castle of Miromesnil which he describes in Une

Vie. . . .

Maupassant, like Flaubert, was a Norman, through his mother, and

through his place of birth he belonged to that strange and

adventurous race, whose heroic and long voyages on tramp trading

ships he liked to recall. And just as the author of "Education

sentimentale" seems to have inherited in the paternal line the

shrewd realism of Champagne, so de Maupassant appears to have

inherited from his Lorraine ancestors their indestructible

discipline and cold lucidity.

His childhood was passed at Etretat, his beautiful childhood; it

was there that his instincts were awakened in the unfoldment of his

prehistoric soul. Years went by in an ecstasy of physical

happiness. The delight of running at full speed through fields of

gorse, the charm of voyages of discovery in hollows and ravines,

games beneath the dark hedges, a passion for going to sea with the

fishermen and, on nights when there was no moon, for dreaming on

their boats of imaginary voyages.

Mme. de Maupassant, who had guided her son's early reading, and had

gazed with him at the sublime spectacle of nature, put, off as long

as possible the hour of separation. One day, however, she had to

take the child to the little seminary at Yvetot. Later, he became a

student at the college at Rouen, and became a literary

correspondent of Louis Bouilhet. It was at the latter's house on

those Sundays in winter when the Norman rain drowned the sound of

the bells and dashed against the window panes that the school boy

learned to write poetry.

Vacation took the rhetorician back to the north of Normandy. Now it

was shooting at Saint Julien l'Hospitalier, across fields, bogs,

and through the woods. From that time on he sealed his pact with

the earth, and those "deep and delicate roots" which attached him

to his native soil began to grow. It was of Normandy, broad, fresh

and virile, that he would presently demand his inspiration, fervent

and eager as a boy's love; it was in her that he would take refuge

when, weary of life, he would implore a truce, or when he simply

wished to work and revive his energies in old-time joys. It was at

this time that was born in him that voluptuous love of the sea,

which in later days could alone withdraw him from the world, calm

him, console him.

In 1870 he lived in the country, then he came to Paris to live;

for, the family fortunes having dwindled, he had to look for a

position. For several years he was a clerk in the Ministry of

Marine, where he turned over musty papers, in the uninteresting

company of the clerks of the admiralty.

Then he went into the department of Public Instruction, where

bureaucratic servility is less intolerable. The daily duties are

certainly scarcely more onerous and he had as chiefs, or

colleagues, Xavier Charmes and Leon Dierx, Henry Roujon and Rene

Billotte, but his office looked out on a beautiful melancholy

garden with immense plane trees around which black circles of crows

gathered in winter.

Maupassant made two divisions of his spare hours, one for boating,

and the other for literature. Every evening in spring, every free

day, he ran down to the river whose mysterious current veiled in

fog or sparkling in the sun called to him and bewitched him. In the

islands in the Seine between Chatou and Port-Marly, on the banks of

Sartrouville and Triel he was long noted among the population of

boatmen, who have now vanished, for his unwearying biceps, his

cynical gaiety of good-fellowship, his unfailing practical jokes,

his broad witticisms. Sometimes he would row with frantic speed,

free and joyous, through the glowing sunlight on the stream;

sometimes, he would wander along the coast, questioning the

sailors, chatting with the ravageurs, or junk gatherers, or

stretched at full length amid the irises and tansy he would lie for

hours watching the frail insects that play on the surface of the

stream, water spiders, or white butterflies, dragon flies, chasing

each other amid the willow leaves, or frogs asleep on the

lily-pads.

The rest of his life was taken up by his work. Without ever

becoming despondent, silent and persistent, he accumulated

manuscripts, poetry, criticisms, plays, romances and novels. Every

week he docilely submitted his work to the great Flaubert, the

childhood friend of his mother and his uncle Alfred Le Poittevin.

The master had consented to assist the young man, to reveal to him

the secrets that make chefs-d'oeuvre immortal. It was he who

compelled him to make copious research and to use direct

observation and who inculcated in him a horror of vulgarity and a

contempt for facility.

Maupassant himself tells us of those severe initiations in the Rue

Murillo, or in the tent at Croisset; he has recalled the implacable

didactics of his old master, his tender brutality, the paternal

advice of his generous and candid heart. For seven years Flaubert

slashed, pulverized, the awkward attempts of his pupil whose

success remained uncertain.

Suddenly, in a flight of spontaneous perfection, he wrote Boule de

Suif. His master's joy was great and overwhelming. He died two

months later.

Until the end Maupassant remained illuminated by the reflection of

the good, vanished giant, by that touching reflection that comes

from the dead to those souls they have so profoundly stirred. The

worship of Flaubert was a religion from which nothing could

distract him, neither work, nor glory, nor slow moving waves, nor

balmy nights.

At the end of his short life, while his mind was still clear: he

wrote to a friend: "I am always thinking of my poor Flaubert, and I

say to myself that I should like to die if I were sure that anyone

would think of me in the same manner."

During these long years of his novitiate Maupassant had entered the

social literary circles. He would remain silent, preoccupied; and

if anyone, astonished at his silence, asked him about his plans he

answered simply: "I am learning my trade." However, under the

pseudonym of Guy de Valmont, he had sent some articles to the

newspapers, and, later, with the approval and by the advice of

Flaubert, he published, in the "Republique des Lettres," poems

signed by his name.

These poems, overflowing with sensuality, where the hymn to the

Earth describes the transports of physical possession, where the

impatience of love expresses itself in loud melancholy appeals like

the calls of animals in the spring nights, are valuable chiefly

inasmuch as they reveal the creature of instinct, the fawn escaped

from his native forests, that Maupassant was in his early youth.

But they add nothing to his glory. They are the "rhymes of a prose

writer" as Jules Lemaitre said. To mould the expression of his

thought according to the strictest laws, and to "narrow it down" to

some extent, such was his aim. Following the example of one of his

comrades of Medan, being readily carried away by precision of style

and the rhythm of sentences, by the imperious rule of the ballad,

of the pantoum or the chant royal, Maupassant also desired to write

in metrical lines. However, he never liked this collection that he

often regretted having published. His encounters with prosody had

left him with that monotonous weariness that the horseman and the

fencer feel after a period in the riding school, or a bout with the

foils.

Such, in very broad lines, is the story of Maupassant's literary

apprenticeship.

The day following the publication of "Boule de Suif," his

reputation began to grow rapidly. The quality of his story was

unrivalled, but at the same time it must be acknowledged that there

were some who, for the sake of discussion, desired to place a young

reputation in opposition to the triumphant brutality of Zola.

From this time on, Maupassant, at the solicitation of the entire

press, set to work and wrote story after story. His talent, free

from all influences, his individuality, are not disputed for a

moment. With a quick step, steady and alert, he advanced to fame, a

fame of which he himself was not aware, but which was so universal,

that no contemporary author during his life ever experienced the

same. The "meteor" sent out its light and its rays were prolonged

without limit, in article after article, volume on volume.

He was now rich and famous . . . . He is esteemed all the more as

they believe him to be rich and happy. But they do not know that

this young fellow with the sunburnt face, thick neck and salient

muscles whom they invariably compare to a young bull at liberty,

and whose love affairs they whisper, is ill, very ill. At the very

moment that success came to him, the malady that never afterwards

left him came also, and, seated motionless at his side, gazed at

him with its threatening countenance. He suffered from terrible

headaches, followed by nights of insomnia. He had nervous attacks,

which he soothed with narcotics and anesthetics, which he used

freely. His sight, which had troubled him at intervals, became

affected, and a celebrated oculist spoke of abnormality, asymetry

of the pupils. The famous young man trembled in secret and was

haunted by all kinds of terrors.

The reader is charmed at the saneness of this revived art and yet,

here and there, he is surprised to discover, amid descriptions of

nature that are full of humanity, disquieting flights towards the

supernatural, distressing conjurations, veiled at first, of the

most commonplace, the most vertiginous shuddering fits of fear, as

old as the world and as eternal as the unknown. But, instead of

being alarmed, he thinks that the author must be gifted with

infallible intuition to follow out thus the taints in his

characters, even through their most dangerous mazes. The reader

does not know that these hallucinations which he describes so

minutely were experienced by Maupassant himself; he does not know

that the fear is in himself, the anguish of fear "which is not

caused by the presence of danger, or of inevitable death, but by

certain abnormal conditions, by certain mysterious influences in

presence of vague dangers," the "fear of fear, the dread of that

horrible sensation of incomprehensible terror."

How can one explain these physical sufferings and this morbid

distress that were known for some time to his intimates alone?

Alas! the explanation is only too simple. All his life, consciously

or unconsciously, Maupassant fought this malady, hidden as yet,

which was latent in him.

As his malady began to take a more definite form, he turned his

steps towards the south, only visiting Paris to see his physicians

and publishers. In the old port of Antibes beyond the causeway of

Cannes, his yacht, Bel Ami, which he cherished as a brother, lay at

anchor and awaited him. He took it to the white cities of the

Genoese Gulf, towards the palm trees of Hyeres, or the red bay

trees of Antheor.

After several tragic weeks in which, from instinct, he made a

desperate fight, on the 1st of January, 1892, he felt he was

hopelessly vanquished, and in a moment of supreme clearness of

intellect, like Gerard de Nerval, he attempted suicide. Less

fortunate than the author of Sylvia, he was unsuccessful. But his

mind, henceforth "indifferent to all unhappiness," had entered into

eternal darkness.

He was taken back to Paris and placed in Dr. Meuriot's sanatorium,

where, after eighteen months of mechanical existence, the "meteor"

quietly passed away.

TWO FRIENDS

Besieged Paris was in the throes of famine. Even the sparrows on

the roofs and the rats in the sewers were growing scarce. People

were eating anything they could get.

As Monsieur Morissot, watchmaker by profession and idler for the

nonce, was strolling along the boulevard one bright January

morning, his hands in his trousers pockets and stomach empty, he

suddenly came face to face with an acquaintance—Monsieur Sauvage, a

fishing chum.

Before the war broke out Morissot had been in the habit, every

Sunday morning, of setting forth with a bamboo rod in his hand and

a tin box on his back. He took the Argenteuil train, got out at

Colombes, and walked thence to the Ile Marante. The moment he

arrived at this place of his dreams he began fishing, and fished

till nightfall.

Every Sunday he met in this very spot Monsieur Sauvage, a stout,

jolly, little man, a draper in the Rue Notre Dame de Lorette, and

also an ardent fisherman. They often spent half the day side by

side, rod in hand and feet dangling over the water, and a warm

friendship had sprung up between the two.

Some days they did not speak; at other times they chatted; but they

understood each other perfectly without the aid of words, having

similar tastes and feelings.

In the spring, about ten o'clock in the morning, when the early sun

caused a light mist to float on the water and gently warmed the

backs of the two enthusiastic anglers, Morissot would occasionally

remark to his neighbor:

"My, but it's pleasant here."

To which the other would reply:

"I can't imagine anything better!"

And these few words sufficed to make them understand and appreciate

each other.

In the autumn, toward the close of day, when the setting sun shed a

blood-red glow over the western sky, and the reflection of the

crimson clouds tinged the whole river with red, brought a glow to

the faces of the two friends, and gilded the trees, whose leaves

were already turning at the first chill touch of winter, Monsieur

Sauvage would sometimes smile at Morissot, and say:

"What a glorious spectacle!"

And Morissot would answer, without taking his eyes from his

float:

"This is much better than the boulevard, isn't it?"

As soon as they recognized each other they shook hands cordially,

affected at the thought of meeting under such changed

circumstances.

Monsieur Sauvage, with a sigh, murmured:

"These are sad times!"

Morissot shook his head mournfully.

"And such weather! This is the first fine day of the year."

The sky was, in fact, of a bright, cloudless blue.

They walked along, side by side, reflective and sad.

"And to think of the fishing!" said Morissot. "What good times we

used to have!"

"When shall we be able to fish again?" asked Monsieur

Sauvage.

They entered a small cafe and took an absinthe together, then

resumed their walk along the pavement.

Morissot stopped suddenly.

"Shall we have another absinthe?" he said.

"If you like," agreed Monsieur Sauvage.

And they entered another wine shop.

They were quite unsteady when they came out, owing to the effect of

the alcohol on their empty stomachs. It was a fine, mild day, and a

gentle breeze fanned their faces.

The fresh air completed the effect of the alcohol on Monsieur

Sauvage. He stopped suddenly, saying:

"Suppose we go there?"

"Where?"

"Fishing."

"But where?"

"Why, to the old place. The French outposts are close to Colombes.

I know Colonel Dumoulin, and we shall easily get leave to

pass."

Morissot trembled with desire.

"Very well. I agree."

And they separated, to fetch their rods and lines.

An hour later they were walking side by side on the-highroad.

Presently they reached the villa occupied by the colonel. He smiled

at their request, and granted it. They resumed their walk,

furnished with a password.

Soon they left the outposts behind them, made their way through

deserted Colombes, and found themselves on the outskirts of the

small vineyards which border the Seine. It was about eleven

o'clock.

Before them lay the village of Argenteuil, apparently lifeless. The

heights of Orgement and Sannois dominated the landscape. The great

plain, extending as far as Nanterre, was empty, quite empty-a waste

of dun-colored soil and bare cherry trees.

Monsieur Sauvage, pointing to the heights, murmured:

"The Prussians are up yonder!"

And the sight of the deserted country filled the two friends with

vague misgivings.

The Prussians! They had never seen them as yet, but they had felt

their presence in the neighborhood of Paris for months past—ruining

France, pillaging, massacring, starving them. And a kind of

superstitious terror mingled with the hatred they already felt

toward this unknown, victorious nation.

"Suppose we were to meet any of them?" said Morissot.

"We'd offer them some fish," replied Monsieur Sauvage, with that

Parisian light-heartedness which nothing can wholly quench.

Still, they hesitated to show themselves in the open country,

overawed by the utter silence which reigned around them.

At last Monsieur Sauvage said boldly:

"Come, we'll make a start; only let us be careful!"

And they made their way through one of the vineyards, bent double,

creeping along beneath the cover afforded by the vines, with eye

and ear alert.

A strip of bare ground remained to be crossed before they could

gain the river bank. They ran across this, and, as soon as they

were at the water's edge, concealed themselves among the dry

reeds.

Morissot placed his ear to the ground, to ascertain, if possible,

whether footsteps were coming their way. He heard nothing. They

seemed to be utterly alone.

Their confidence was restored, and they began to fish.

Before them the deserted Ile Marante hid them from the farther

shore. The little restaurant was closed, and looked as if it had

been deserted for years.

Monsieur Sauvage caught the first gudgeon, Monsieur Morissot the

second, and almost every moment one or other raised his line with a

little, glittering, silvery fish wriggling at the end; they were

having excellent sport.

They slipped their catch gently into a close-meshed bag lying at

their feet; they were filled with joy—the joy of once more

indulging in a pastime of which they had long been deprived.

The sun poured its rays on their backs; they no longer heard

anything or thought of anything. They ignored the rest of the

world; they were fishing.

But suddenly a rumbling sound, which seemed to come from the bowels

of the earth, shook the ground beneath them: the cannon were

resuming their thunder.

Morissot turned his head and could see toward the left, beyond the

banks of the river, the formidable outline of Mont-Valerien, from

whose summit arose a white puff of smoke.

The next instant a second puff followed the first, and in a few

moments a fresh detonation made the earth tremble.

Others followed, and minute by minute the mountain gave forth its

deadly breath and a white puff of smoke, which rose slowly into the

peaceful heaven and floated above the summit of the cliff.

Monsieur Sauvage shrugged his shoulders.

"They are at it again!" he said.

Morissot, who was anxiously watching his float bobbing up and down,

was suddenly seized with the angry impatience of a peaceful man

toward the madmen who were firing thus, and remarked

indignantly:

"What fools they are to kill one another like that!"

"They're worse than animals," replied Monsieur Sauvage.

And Morissot, who had just caught a bleak, declared:

"And to think that it will be just the same so long as there are

governments!"

"The Republic would not have declared war," interposed Monsieur

Sauvage.

Morissot interrupted him:

"Under a king we have foreign wars; under a republic we have civil

war."

And the two began placidly discussing political problems with the

sound common sense of peaceful, matter-of-fact citizens—agreeing on

one point: that they would never be free. And Mont-Valerien

thundered ceaselessly, demolishing the houses of the French with

its cannon balls, grinding lives of men to powder, destroying many

a dream, many a cherished hope, many a prospective happiness;

ruthlessly causing endless woe and suffering in the hearts of

wives, of daughters, of mothers, in other lands.

"Such is life!" declared Monsieur Sauvage.

"Say, rather, such is death!" replied Morissot, laughing.

But they suddenly trembled with alarm at the sound of footsteps

behind them, and, turning round, they perceived close at hand four

tall, bearded men, dressed after the manner of livery servants and

wearing flat caps on their heads. They were covering the two

anglers with their rifles.

The rods slipped from their owners' grasp and floated away down the

river.

In the space of a few seconds they were seized, bound, thrown into

a boat, and taken across to the Ile Marante.

And behind the house they had thought deserted were about a score

of German soldiers.

A shaggy-looking giant, who was bestriding a chair and smoking a

long clay pipe, addressed them in excellent French with the

words:

"Well, gentlemen, have you had good luck with your fishing?"

Then a soldier deposited at the officer's feet the bag full of

fish, which he had taken care to bring away. The Prussian

smiled.

"Not bad, I see. But we have something else to talk about. Listen

to me, and don't be alarmed:

"You must know that, in my eyes, you are two spies sent to

reconnoitre me and my movements. Naturally, I capture you and I

shoot you. You pretended to be fishing, the better to disguise your

real errand. You have fallen into my hands, and must take the

consequences. Such is war.

"But as you came here through the outposts you must have a password

for your return. Tell me that password and I will let you

go."

The two friends, pale as death, stood silently side by side, a

slight fluttering of the hands alone betraying their emotion.

"No one will ever know," continued the officer. "You will return

peacefully to your homes, and the secret will disappear with you.

If you refuse, it means death-instant death. Choose!"

They stood motionless, and did not open their lips.

The Prussian, perfectly calm, went on, with hand outstretched

toward the river:

"Just think that in five minutes you will be at the bottom of that

water. In five minutes! You have relations, I presume?"

Mont-Valerien still thundered.

The two fishermen remained silent. The German turned and gave an

order in his own language. Then he moved his chair a little way

off, that he might not be so near the prisoners, and a dozen men

stepped forward, rifle in hand, and took up a position, twenty

paces off.

"I give you one minute," said the officer; "not a second

longer."

Then he rose quickly, went over to the two Frenchmen, took Morissot

by the arm, led him a short distance off, and said in a low

voice:

"Quick! the password! Your friend will know nothing. I will pretend

to relent."

Morissot answered not a word.

Then the Prussian took Monsieur Sauvage aside in like manner, and

made him the same proposal.

Monsieur Sauvage made no reply.

Again they stood side by side.

The officer issued his orders; the soldiers raised their

rifles.

Then by chance Morissot's eyes fell on the bag full of gudgeon

lying in the grass a few feet from him.

A ray of sunlight made the still quivering fish glisten like

silver. And Morissot's heart sank. Despite his efforts at

self-control his eyes filled with tears.

"Good-by, Monsieur Sauvage," he faltered.

"Good-by, Monsieur Morissot," replied Sauvage.

They shook hands, trembling from head to foot with a dread beyond

their mastery.

The officer cried:

"Fire!"

The twelve shots were as one.

Monsieur Sauvage fell forward instantaneously. Morissot, being the

taller, swayed slightly and fell across his friend with face turned

skyward and blood oozing from a rent in the breast of his

coat.

The German issued fresh orders.

His men dispersed, and presently returned with ropes and large

stones, which they attached to the feet of the two friends; then

they carried them to the river bank.

Mont-Valerien, its summit now enshrouded in smoke, still continued

to thunder.

Two soldiers took Morissot by the head and the feet; two others did

the same with Sauvage. The bodies, swung lustily by strong hands,

were cast to a distance, and, describing a curve, fell feet

foremost into the stream.

The water splashed high, foamed, eddied, then grew calm; tiny waves

lapped the shore.

A few streaks of blood flecked the surface of the river.

The officer, calm throughout, remarked, with grim humor:

"It's the fishes' turn now!"

Then he retraced his way to the house.

Suddenly he caught sight of the net full of gudgeons, lying

forgotten in the grass. He picked it up, examined it, smiled, and

called:

"Wilhelm!"

A white-aproned soldier responded to the summons, and the Prussian,

tossing him the catch of the two murdered men, said:

"Have these fish fried for me at once, while they are still alive;

they'll make a tasty dish."

Then he resumed his pipe.