1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

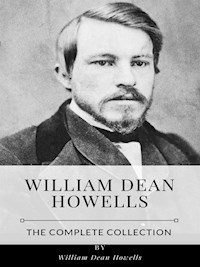

In "Studies of Lowell," a pivotal work from his series "Literary Friends and Acquaintance," William Dean Howells delves into the life and contributions of the esteemed poet James Russell Lowell and his significance in American literature. This book showcases Howells' nuanced literary style, characterized by keen observations and a conversational tone that brings forth an intimate understanding of Lowell's personality and literary prowess. Set against the backdrop of 19th-century America, Howells situates Lowell within the broader currents of Transcendentalism and the emerging American literary identity, allowing readers to grasp the complexities of social and artistic influences of the time. William Dean Howells, often referred to as the "Dean of American Letters," was deeply embedded in the literary milieu of his era. His extensive friendships with contemporaries, such as Lowell, informed his critical perspective and enriched his writing. Howells' commitment to realism and his advocacy for a distinctly American voice in literature shaped his desire to honor Lowell's legacy while reflecting on broader societal themes, such as nationalism and moral responsibility. "Studies of Lowell" is an essential read for anyone interested in American literature, offering both an homage to a literary giant and insightful commentary on the cultural landscape of his time. Readers will appreciate Howells' articulate reflections and the manner in which he captures the spirit of an era, making this work a valuable addition to the understanding of American literary heritage.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

Studies of Lowell (from Literary Friends and Acquaintance)

Table of Contents

I.

It was in the summer of 1865 that I came home from my consular post at Venice; and two weeks after I landed in Boston, I went out to see Lowell at Elmwood, and give him an inkstand that I had brought him from Italy. The bronze lobster whose back opened and disclosed an inkpot and a sand-box was quite ugly; but I thought it beautiful then, and if Lowell thought otherwise he never did anything to let me know it. He put the thing in the middle of his writing-table (he nearly always wrote on a pasteboard pad resting upon his knees), and there it remained as long as I knew the place—a matter of twenty-five years; but in all that time I suppose the inkpot continued as dry as the sand-box.

My visit was in the heat of August, which is as fervid in Cambridge as it can well be anywhere, and I still have a sense of his study windows lifted to the summer night, and the crickets and grasshoppers crying in at them from the lawns and the gardens outside. Other people went away from Cambridge in the summer to the sea and to the mountains, but Lowell always stayed at Elmwood, in an impassioned love for his home and for his town. I must have found him there in the afternoon, and he must have made me sup with him (dinner was at two o'clock) and then go with him for a long night of talk in his study. He liked to have some one help him idle the time away, and keep him as long as possible from his work; and no doubt I was impersonally serving his turn in this way, aside from any pleasure he might have had in my company as some one he had always been kind to, and as a fresh arrival from the Italy dear to us both.

He lighted his pipe, and from the depths of his easychair, invited my shy youth to all the ease it was capable of in his presence. It was not much; I loved him, and he gave me reason to think that he was fond of me, but in Lowell I was always conscious of an older and closer and stricter civilization than my own, an unbroken tradition, a more authoritative status. His democracy was more of the head and mine more of the heart, and his denied the equality which mine affirmed. But his nature was so noble and his reason so tolerant that whenever in our long acquaintance I found it well to come to open rebellion, as I more than once did, he admitted my right of insurrection, and never resented the outbreak. I disliked to differ with him, and perhaps he subtly felt this so much that he would not dislike me for doing it. He even suffered being taxed with inconsistency, and where he saw that he had not been quite just, he would take punishment for his error, with a contrition that was sometimes humorous and always touching.

Just then it was the dark hour before the dawn with Italy, and he was interested but not much encouraged by what I could tell him of the feeling in Venice against the Austrians. He seemed to reserve a like scepticism concerning the fine things I was hoping for the Italians in literature, and he confessed an interest in the facts treated which in the retrospect, I am aware, was more tolerant than participant of my enthusiasm. That was always Lowell's attitude towards the opinions of people he liked, when he could not go their lengths with them, and nothing was more characteristic of his affectionate nature and his just intelligence. He was a man of the most strenuous convictions, but he loved many sorts of people whose convictions he disagreed with, and he suffered even prejudices counter to his own if they were not ignoble. In the whimsicalities of others he delighted as much as in his own.

II.

Our associations with Italy held over until the next day, when after breakfast he went with me towards Boston as far as "the village": for so he liked to speak of Cambridge in the custom of his younger days when wide tracts of meadow separated Harvard Square from his life-long home at Elmwood. We stood on the platform of the horsecar together, and when I objected to his paying my fare in the American fashion, he allowed that the Italian usage of each paying for himself was the politer way. He would not commit himself about my returning to Venice (for I had not given up my place, yet, and was away on leave), but he intimated his distrust of the flattering conditions of life abroad. He said it was charming to be treated 'da signore', but he seemed to doubt whether it was well; and in this as in all other things he showed his final fealty to the American ideal.

It was that serious and great moment after the successful close of the civil war when the republican consciousness was more robust in us than ever before or since; but I cannot recall any reference to the historical interest of the time in Lowell's talk. It had been all about literature and about travel; and now with the suggestion of the word village it began to be a little about his youth. I have said before how reluctant he was to let his youth go from him; and perhaps the touch with my juniority had made him realize how near he was to fifty, and set him thinking of the past which had sorrows in it to age him beyond his years. He would never speak of these, though he often spoke of the past. He told once of having been on a brief journey when he was six years old, with his father, and of driving up to the gate of Elmwood in the evening, and his father saying, "Ah, this is a pleasant place! I wonder who lives here—what little boy?" At another time he pointed out a certain window in his study, and said he could see himself standing by it when he could only get his chin on the window-sill. His memories of the house, and of everything belonging to it, were very tender; but he could laugh over an escapade of his youth when he helped his fellow-students pull down his father's fences, in the pure zeal of good-comradeship.