Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Al-Mashreq eBookstore

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

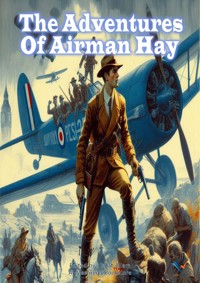

The Adventures of Airman Hay by Edgar Wallace takes readers on a thrilling journey through the skies. Airman Hay, a daring pilot with a knack for finding danger, embarks on a series of high-flying missions filled with espionage, peril, and pulse-pounding action. Whether he's evading enemy aircraft or uncovering treacherous plots, Hay's courage and ingenuity make him a hero you can't help but root for. From the cockpit to the battlefield, this story will keep readers riveted with its high-stakes drama and adventurous spirit. Strap in and prepare for an exhilarating ride through the clouds!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 191

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE ADVENTURES OF AIRMAN HAY

Author: Edgar Wallace

Edited by: Seif Moawad

Copyright © 2024 by Al-Mashreq eBookstore

Published as:

"The Exploits of Airman Hay" in Topical Times, Dundee, Aug 30-Nov 1, 1924

"The Hazards of 'Headstrong' Hay" in The Sunday Post, Glasgow, Jun 28-Aug 30, 1931

No part of this publication may be reproduced whole or in part in any form without the prior written permission of the author

All rights reserved.

Table of Contents

THE ADVENTURES OF AIRMAN HAY

BIBLIOGRAPHIC NOTE

I. — THE GOOD TURNS OF AIRMAN HAY

II. — THE IMPERIOUS LADY

III. — THE BIRTHDAY GREETING

IV. — THE MYSTERIOUS KIDNAPPER

V. — THE OXYGEN MAN

VI. — THE PASSING OF THE PROFESSOR

VII. — THE WOMAN FROM BRIXTON

VIII. — THE FIREMAN

IX — THE CLASSICAL SCHOLAR

X. — THE VAMPIRE

Landmarks

Cover

BIBLIOGRAPHIC NOTE

RGL is proud to offer its readers the first-ever book edition of another "lost" work by Edgar Wallace—a series of ten stories about an intrepid aviator by the name of Captain Murray Hay. The series appeared in at least two periodical publications under different titles:

• "The Exploits of Airman Hay"

(Topical Times, D.C. Thompson, Dundee, Aug 30-Nov 1, 1924)

• "The Hazards of 'Headstrong' Hay"

(The Sunday Post, Glasgow, Jun 28-Aug 31, 1931)

I. — THE GOOD TURNS OF AIRMAN HAY

With a little pang of contrition Murray Hay realised that it was so long since he had been to Elbury that even the station porter, who was also station-master and ticket collector, did not recognise him. And this discovery added to his gloom.

He had caught an earlier train than he planned, and since his uncle would not expect him before three o'clock, he decided to lunch at the Red Lion. And even the Red Lion had changed its proprietor and staff since those hectic days of 1914 when he had come to say good-bye to his indulgent relative before plunging into four years of horror and thrill.

There was one other traveller in the coffee-room when he went in, a tall, thin man in a golfing suit, who was lunching at leisure, reading a newspaper when Murray arrived, and scarcely looked up to see the newcomer.

Taking stock of him, Murray guessed that his age was somewhere in the neighbourhood of forty. His face was thin and lined and a red diagonal scar ran from his right cheek to his chin. The young man's first impression was that his fellow guest was a foreigner, and this was confirmed when, looking suddenly over his paper, the man said:

"Good morning, m'sieur. You are a stranger here, yes?"

"I'm afraid I am in these days," smiled Murray ruefully.

"Ah! It is a beautiful place, of all places, most exquisite! I also, am a stranger."

Murray was not really interested and uttered some commonplace, for he had all the Britisher's aversion to conversation with strangers.

He paid his bill and set off on the three mile walk which separated him from Elbury Park. Even the lodge-keeper was new to him and eyed him suspiciously as he swung up the elm drive, and when he rang the bell of Elbury Manor and the door was opened by the prettiest girl that ever wore maid's uniform, his sensation of change was complete. Her flawless skin and fine, dark eyes were altogether entrancing, and for a second he was speechless with wonder and admiration.

"Mr. Hay? Yes, sir. Sir John is expecting you."

She preceded the dazzled young man to the library door and knocked. In another few seconds he was shaking hands with the bluff white-haired man who was his only relative.

"Changed, has it, you young dog! If you had been a dutiful nephew and paid me a visit or two, you wouldn't have noticed the change! However... sit down. Have a cigar."

"I missed old Thomas," said Murray.

"I pensioned him off. What do you think of the new maid?"

"She's beautiful," said Murray, with an enthusiasm he did not attempt to conceal.

"She's efficient," said the other practically, "and that is all that counts. She is pretty, though."

Sir John paced the floor, his hands in his pockets. Presently he stopped before the big glass case that contained his priceless gold plate—the £100,000 worth of the goldsmith's art that had taken a lifetime to collect.

"You wonder why I sent for you?" he asked. "The truth is, Murray, you're rapidly developing into a waster. No, no, I don't mean that you're becoming a blackguard, but just what I say: a waster of time, a waster of money, a waste of opportunity. Life to you is a glorified amusement park, if you'll excuse the Wembley illustration. The Palace of Industry means nothing to you; It Is the Giant Racer and the Scenic Railway that occupy your mind and thoughts. That isn't good for a young man."

Sir John Harlesden sat down in his chair, selected a cigar from a silver box on the table, and smiled quizzically at the disconsolate young man who sat opposite to him. Murray was a good-looking, clean-cut youth, the type that public schools and Sandhurst turn out yearly by the thousand.

"I'm a rich man," the other went on, "and you are my only relative, which means that you have instinctively come to look upon me as a sort of gilt-edged investment that will yield you money without the necessity of working for it. You have, in fact, become a sponger."

Murray writhed at the word. Sir John leant his elbows on the table and regarded his nephew with a critical eye.

"You're a decent boy; you've all sorts of medals and decorations for the work you did in the war. But wars are mere incidents which occur at intervals of a hundred years, and there is something to be done besides shooting down Germans from the air. Anyway, if you did it to-day, you'd be tried for wilful murder!"

"What do you want me to do?" asked Murray.

He was not the type that sulked; indeed, he recognised the absolute truth of all his uncle had said.

Sir John puffed a cloud of smoke into the air before he replied.

"I've been thinking it over. When I die, there's a million pounds for you, and I've had serious thoughts of transferring that amount to you during my lifetime. This appeals more to me than putting your name in my will, because I hate the thought that anybody is going to benefit by my death! At present you have an allowance of five thousand a year, which is more than any young man should have to chuck about. If I were a manufacturing millionaire or a merchant prince or one of these captains of industry that one reads about, it would be a simple matter to put you in one of my factories. But, fortunately or unfortunately, I made my money in the larger field of finance. And really I have no desire that you should go into business. You'd be an awful duffer, anyway. Your spelling is execrable and your knowledge of figures would bring the blush of shame to a child of six."

He opened a drawer, took out a paper covered with writing and, laying it on the pad in front of him, consulted his notes.

"In order that you should keep up your flying, I bought you a couple of fast machines; I've got you a private aerodrome and I pay the wages of three or four mechanics."

"You want me to turn the thing into a commercial hire company?" asked Murray eagerly. "Why, of course I will, uncle. I've thought about it before."

Sir John shook his head.

"I don't want you to do anything of the kind," he said. "I wish to inculcate the Boy Scout spirit. Murray, I ask of you"—he spoke deliberately, emphasising each sentence with a tap on his blotting-pad—"that in the course of the next year you perform eight good turns."

"Eight good turns?" repeated the dumbfounded young man. "You mean—?"

"I mean that you shall render eight acts of service to people who cannot afford to pay you and for whom these services are vital."

Murray's jaw dropped.

"But how the dickens am I going to find out—?" he began. "And what about the good turn I am doing on Saturday? I'm giving a stunt exhibition at the Police Festival at Wimbledon. I'm doing this without fee—"

"That doesn't count," said Sir John, with a twinkle in his eye. "And you will best discover how you can help by mixing with the people of the world; by bringing yourself into acquaintance with the needs of your fellow creatures. I don't mind your advertising,"—A light came into Murray's eyes—"but apart from the difficulty you'll have of sorting out the genuine cases from the fakes, you've got to prove to me that you have added to the sum of the world's happiness by your good actions. That is all. I have no suggestion to make as to how you will go about your task: only your eight deeds must satisfy me as to their disinterestedness. I've no doubt that you will find ample compensation, for the way of unselfishness is the way of high adventure. And, Murray, you won't find the right kind of people to help if you're frigid and standoffish. Talk to folks in the train... I'll bet you're the kind that could go from London to Aberdeen with one fellow passenger and never utter a word except to ask him if he minded the window being down!"

Murray remembered guiltily his taciturn treatment of the guest at the Red Lion.

"Now, off you go—be helpful, be of use in the world—and keep your eyes off my new parlourmaid!"

Ten minutes later, Murray Hay was walking down the drive like a man in a dream. How typical of old Sir John Harlesden this scheme was! For Sir John was something of an original, and it was he who, for a bet, sent a messenger boy around the world in seventy days.

Presently the humour of the situation took hold of him and Murray grinned. Eight good turns! There must he millions of people in the world who wanted something done for them. But did that something take the shape of a free ride in an aeroplane?

As he walked, he looked round, hoping to find some damsel stranded, some old man in distress, until he realised that he had not the wherewithal to help them, even if they existed. As he reached the village and was passing the Red Lion, he saw the stranger in the golfing suit come out, and obviously, by the direction he took, he also was making for the station.

In his then mood, Murray was prepared to be communicative, even to a perfect stranger; and he realised that there was this amount of truth in Sir John Harlesden's words, that he could only discover the needs of his fellows by unbending from his aloof attitude.

There was some time to wait before the train came in, and, seeing the stranger feeling in his pocket for some matches, he made a point of strolling up to him and offering a box.

"That is very kind of you," said the other, beaming. "My name is Lacomte."

"Mine is Murray Hay," said Murray recklessly, overriding the reticence of years. "Are you going to London?"

"Oui—yes, I am going to London. It is a wonderful city, but too noisy. And for me, distracted as I am"—he clasped his brow dramatically—"it is maddening!"

As they took their seats in the same carriage, Murray wondered whether it would be also maddening for him, for he had his own problem, which could not be any less poignant than M. Lacomte's.

"You are in trouble also?" said the Frenchman, with quick intuition.

Murray hesitated.

"Well—yes," he admitted. And then, in his new mood of expansiveness, he went on: "You see, I am in a sort of a hole." Again he hesitated, but with an effort he continued. "I am an airman," he began.

"An aviateur?" said the other, with sudden interest, and Murray nodded.

"I have my own machine. And I am afraid I've rather wasted a lot of time and money barging around"—he hurriedly explained in his best French the meaning of the verb 'to barge', which had puzzled the stranger. "And now a relation of mine has asked me to help people... I mean, do them good turns."

A light dawned in the Frenchman's face.

"Ah, yes, I understand. You are to be more altruistic, and you are to use that aeroplane... extraordinaire!"

Murray thought it was extraordinaire too, but he didn't quite gather the Frenchman's meaning until later.

"So you were here in this little town, looking for persons to whom you could be a benefactor? You do not live here, no?"

Murray shook his head.

"In London, perhaps? This is most extraordinaire!"

Murray did not explain that his visit to Elbury was totally unconnected with a desire to do anybody a turn, unless, in obeying his uncle's somewhat peremptory demand that he should come down, he was helping a less favoured fellow citizen.

The Frenchman was strangely silent for the first part of the journey, and the train was running into the suburbs of London when he suddenly leant forward and, in a low voice asked:

"Is that what you wish—to render service unselfishly, to help the weak, hein?"

"That's the general idea," said Murray miserably. All the way up he had been turning over in his mind every possible and impossible solution of his difficulty.

Again the Frenchman relapsed into silence, which he as unexpectedly broke.

"Monsieur," he said gravely, "there are things happening in this world which few realise. Cruelties perpetrated, wrongs inflicted, desperate and villainous deeds committed, and none are wiser. For not all these things go to the judges at the courts."

Murray looked at him in astonishment, wondering what was coming next.

"Let me tell you a story," said the other. M. Lacomte's voice was low and sad. "Many years ago there lived in the town of Avignon, in France, a young girl, beautiful and accomplished. She had unfortunately a guardian who lived, and still lives, in England, and who coveted the property which came to her at her father's death. The property runs into hundreds of thousands of pounds. No sooner did this scoundrel discover that he was placed in charge of the girl's fortune, than he brought her to England on an excuse; and from that day to this she has never been visible."

Murray Hay's jaw dropped.

"Murdered?" he said incredulously.

The other man shook his head.

"No, monsieur. That she is alive, we, her friends, and the friends of her dear father, know. I said she had not been visible, but she has been seen walking about the grounds of this monster's house, but always by night! By day she is kept looked up in a room, and her meals, we presume, are carried to her by the man himself. Jean Jacques Milfois—a name which may be familiar to you."

Murray shook his head.

"I don't know him from a crow," he admitted, and the Frenchman sighed.

"He is well known, too well known," he said savagely. "Every week, cheques signed by little Adele come to her bank and are honoured. It is impossible to prevent payment. Last Monday I received a letter, which I have not with me, but the gist of which I will communicate to you, monsieur. It was a request from Adele that we save her from a terrible fate. But, monsieur, how can it be done? To take her from her guardian might be easy, though there would be some risk. But to get her from England, with your wonderful complicated police system? Every boat would be watched, every avenue of escape guarded. The bullies he hires to guard her might be overcome. It is possible to reach her window on the outside with the aid of a ladder, but those terrible policemen who stand at the gangways of the outgoing mail steamers, and who watch ceaselessly day and night at Dover and Folkestone, those are my difficulties."

Murray had listened with growing amazement.

"But is this really a fact?" he asked, his hopes suddenly rising. "Do you mean to tell me that here in England, in London...?"

M. Lacomte nodded.

"Your words have filled me with an ecstasy of optimism," he said. Then his face fell. "Can you fly by night?"

Murray could fly by night or day, in fair weather or foul, but he did not say this. Instead, he modestly admitted his ability to find his way across even an unknown country in the dark.

"Always providing that there's a landing place," he added.

"As to that, monsieur," said the other eagerly, "I can tell you that you need have no fear. You say your name is—?"

"Murray Hay," repeated Murray.

"That is a good name, a name which inspires confidence in my heart." He clutched his waistcoat fervently, and then: "Where can I see you to-night?"

Murray's first impulse was to give him the name of his club, but he changed his mind. He remained sufficiently British to hesitate before introducing a volcanic foreigner to that chaste atmosphere. Instead, he gave him the address of his little flat.

At eight o'clock that night, when he was dressing for dinner, the Frenchman called.

"Monsieur, I have news," he said. "I have had a letter from Adele, in which she tells me that Jean Jacques is leaving the house on Saturday. She will he alone. She has bribed a servant and can get into the grounds. Monsieur, can you help me to place this innocent child beyond the machinations of a heartless and contemptible villain?"

This was the question which Murray had been turning over and over in the solitude of his flat ever since he had said good-night to the Frenchman at the station; and he had come to a decision. Here was an act which must come into the category of good deeds, and he had already telephoned to his mechanics to have the machine in readiness.

"That's good news," he said thoughtfully. "I'd sooner make a landing by day than by night."

"At what height can you travel?"

"Anything up to twenty thousand feet," said Murray, and Lacomte's eyes glistened.

"They will not see us at that height. We may pass across to France above the clouds. It is magnificent! And you will help me?"

Murray's answer was to offer his hand.

When, on the Friday, he had a letter from Sir John asking him to accompany the baronet to Scotland for the week-end, it was with a sense of virtue that he wired:

"Sorry. Too busy doing good turns."

On Saturday morning a car called at Letherby Mansions, and the Frenchman was the solitary inmate. He waited impatiently for a quarter of an hour, although he was more than that time ahead of his appointment, for Murray to put in his appearance. At last the young airman came down and joined him.

"It is good weather for flying, yes?" he asked eagerly.

The young man looked up at the scurrying clouds.

"Yes, pretty good," he said.

He was glad enough that his good deed was timed for the early part of the day, for he had promised a very high police official that he would stunt for the benefit of the thousands who attended the annual police festival at noon that day. And he reckoned that he could drop the rescued girl in France and get back before the festival concluded.

The morning was grey, the air cold, and the Frenchman was shivering by the time they reached the little aerodrome at Barnet. Murray Hay's little Scout had been temporarily converted into a three-seater.

"It will be a close fit for you," warned Murray, as he made his way across the landing ground.

"The baggage—we shall have room for that, yes?" asked the Frenchman.

"A little," said Murray, and hoped that M. Lacomte shared his idea as to what was 'a little'.

The Frenchman was examining the machine with every sign of interest. He asked a few questions as to the length of time the machine could be in the air, and seemed satisfied. It occurred to Murray that his passenger had been in the air before, for after he had been enveloped in a heavy leather coat, he strapped himself in with the care of an old campaigner.

"Yes," he said, in answer to the young man's question, "I was once observer in the French Army—never pilot, you understand."

The mechanics made their final inspection; the propeller was spun, and with a deafening roar the propellers flew round in a blue haze. In another second the machine was bumping lightly along the ground. Presently the bumping ceased, and, looking down, Lacomte saw the ground fall away.

Higher and higher the aeroplane mounted, and now London lay beneath them, veiled under a blue layer of smoke. Presently Murray heard the telephone receiver at his ear.

"To the west!"

It had been arranged that his destination should be kept a secret until the last moment; an understandable precaution, thought the airman, though it was rather a nuisance not knowing the direction he was to take.

London was behind them now, and beneath a thin white twisting ribbon that Murray knew to be the Thames.

"Bear a little northward," said the voice in his ear, and he obeyed.

They flew for half-an-hour before Lacomte again corrected the direction. He was studying a map intently, and a quarter of an hour later:

"You will go north now and look for the two spires of Alchester Cathedral," he said.

Alchester Cathedral? That was near Elbury. Then in what place was this unfortunate girl imprisoned? Murray knew all the big houses for miles around, but he could not place Jean Jacques Milfois.

Fire minutes' flying, and ahead of him he saw the broad green of Elbury Park and chuckled. Little did Sir John know that the first good turn was progressing towards completion.

And then, to his amazement, Lacomte's voice roared:

"Descendez! On the green—there!" His lean, brown finger pointed, and Murray almost jumped out of his seat in his amazement.

He was to come down in Elbury Park!

"Is that the place where the girl is kept prisoner?" he asked, through the microphone.

"Oui, it is there."

But for the wind that would have blown the sound back between his teeth, Murray would have whistled. Obediently he dipped the nose of his Scout, missed the high poplars that skirted the western boundary, and touched ground out of sight but within a few hundred yards of the house. And then he saw a figure run from the shelter of the rhododendrons towards him.

"Do not stop your engine!" shouted Lacomte.

The figure was a woman, and she carried with difficulty a great bundle. Even as the machine came to a standstill, she was beside the cockpit and Lacomte had hauled the bundle on board. There was a musical sound of clinking metal, and out of the corner of his goggled eyes Murray saw the pretty maid. She was dressed for the journey, buttoned to the chin, a leather cap strapped over her dark hair, and goggles fastened across her forehead. In a few seconds she had followed the man and was strapping herself by the side of Lacomte.

"Allez!" hissed the Frenchman's voice. "For France!"