Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: SAMPI Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

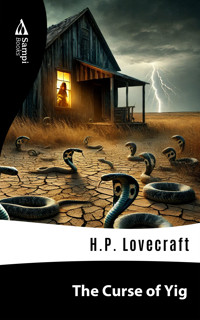

"The Curse of Yig" tells the eerie story of a man named Walker Davis, who, in the early 20th century, becomes obsessed with Native American legends while living in Oklahoma. Particularly haunted by the tale of Yig, a snake god believed to curse anyone who kills a snake, Walker's fear grows into paranoia. He becomes so terrified of Yig's supposed curse that he falls into a series of disturbing events that spiral toward madness, revealing the terrifying power of belief in curses and folklore.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 33

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Curse of Yig

H.P. Lovecraft

SYNOPSIS

“The Curse of Yig” tells the eerie story of a man named Walker Davis, who, in the early 20th century, becomes obsessed with Native American legends while living in Oklahoma. Particularly haunted by the tale of Yig, a snake god believed to curse anyone who kills a snake, Walker’s fear grows into paranoia. He becomes so terrified of Yig’s supposed curse that he falls into a series of disturbing events that spiral toward madness, revealing the terrifying power of belief in curses and folklore.

Keywords

Paranoia, folklore, madness.

NOTICE

This text is a work in the public domain and reflects the norms, values and perspectives of its time. Some readers may find parts of this content offensive or disturbing, given the evolution in social norms and in our collective understanding of issues of equality, human rights and mutual respect. We ask readers to approach this material with an understanding of the historical era in which it was written, recognizing that it may contain language, ideas or descriptions that are incompatible with today's ethical and moral standards.

Names from foreign languages will be preserved in their original form, with no translation.

The Curse of Yig

In 1925 I went into Oklahoma looking for snake lore, and I came out with a fear of snakes that will last me the rest of my life. I admit it is foolish, since there are natural explanations for everything I saw and heard, but it masters me none the less. If the old story had been all there was to it, I would not have been so badly shaken. My work as an American Indian ethnologist has hardened me to all kinds of extravagant legendary, and I know that simple white people can beat the redskins at their own game when it comes to fanciful inventions. But I can’t forget what I saw with my own eyes at the insane asylum in Guthrie.

I called at that asylum because a few of the oldest settlers told me I would find something important there. Neither Indians nor white men would discuss the snake-god legends I had come to trace. The oil-boom newcomers, of course, knew nothing of such matters, and the red men and old pioneers were plainly frightened when I spoke of them. Not more than six or seven people mentioned the asylum, and those who did were careful to talk in whispers. But the whisperers said that Dr. McNeill could shew me a very terrible relic and tell me all I wanted to know. He could explain why Yig, the half-human father of serpents, is a shunned and feared object in central Oklahoma, and why old settlers shiver at the secret Indian orgies which make the autumn days and nights hideous with the ceaseless beating of tom-toms in lonely places.

It was with the scent of a hound on the trail that I went to Guthrie, for I had spent many years collecting data on the evolution of serpent-worship among the Indians. I had always felt, from well-defined undertones of legend and archaeology, that great Quetzalcoatl—benign snake-god of the Mexicans—had had an older and darker prototype; and during recent months I had well-nigh proved it in a series of researches stretching from Guatemala to the Oklahoma plains. But everything was tantalizing and incomplete, for above the border the cult of the snake was hedged about by fear and furtiveness.

Now it appeared that a new and copious source of data was about to dawn, and I sought the head of the asylum with an eagerness I did not try to cloak. Dr. McNeill was a small, clean-shaven man of somewhat advanced years, and I saw at once from his speech and manner that he was a scholar of no mean attainments in many branches outside his profession. Grave and doubtful when I first made known my errand, his face grew thoughtful as he carefully scanned my credentials and the letter of introduction which a kindly old ex-Indian agent had given me.