The Editor's Relations with the Young Contributor (from Literature and Life) E-Book

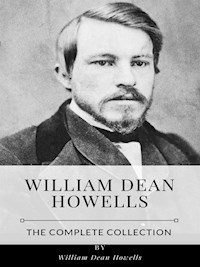

William Dean Howells

1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

In "The Editor's Relations with the Young Contributor," William Dean Howells explores the intricate dynamics between editors and emerging writers within the literary landscape of the late 19th century. This essay, part of his larger work "Literature and Life," blends practical advice with a reflective tone, revealing Howells' deep commitment to nurturing literary voices. Using a conversational style, he examines issues of mentorship, creativity, and the often fraught publishing process, situated in a period marked by the rise of realism and the expansion of American literature. William Dean Howells, a prominent figure in American literature, was not only a prolific novelist but also an accomplished editor and critic, which informs his insights in this work. His career, intertwined with literary personalities like Mark Twain and Henry James, led him to recognize the struggles faced by young writers seeking guidance in an evolving literary market, emphasizing the importance of supportive editorial relationships in fostering talent. "The Editor's Relations with the Young Contributor" serves as an essential read for aspiring writers, editors, and literary scholars alike. Howells' reflections offer timeless wisdom on the collaborative nature of writing and publishing, encouraging readers to appreciate the mentorship roles editors can play in shaping literary careers while advocating for the cultivation of new voices in the literary world.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

The Editor's Relations with the Young Contributor (from Literature and Life)

Table of Contents

I.

The new contributor who does charm can have little notion how much he charms his first reader, who is the editor. That functionary may bide his pleasure in a short, stiff note of acceptance, or he may mask his joy in a check of slender figure; but the contributor may be sure that he has missed no merit in his work, and that he has felt, perhaps far more than the public will feel, such delight as it can give.

The contributor may take the acceptance as a token that his efforts have not been neglected, and that his achievements will always be warmly welcomed; that even his failures will be leniently and reluctantly recognized as failures, and that he must persist long in failure before the friend he has made will finally forsake him.

I do not wish to paint the situation wholly rose color; the editor will have his moods, when he will not see so clearly or judge so justly as at other times; when he will seem exacting and fastidious, and will want this or that mistaken thing done to the story, or poem, or sketch, which the author knows to be simply perfect as it stands; but he is worth bearing with, and he will be constant to the new contributor as long as there is the least hope of him.

The contributor may be the man or the woman of one story, one poem, one sketch, for there are such; but the editor will wait the evidence of indefinite failure to this effect. His hope always is that he or she is the man or the woman of many stories, many poems, many sketches, all as good as the first.

From my own long experience as a magazine editor, I may say that the editor is more doubtful of failure in one who has once done well than of a second success. After all, the writer who can do but one good thing is rarer than people are apt to think in their love of the improbable; but the real danger with a young contributor is that he may become his own rival.

What would have been quite good enough from him in the first instance is not good enough in the second, because he has himself fixed his standard so high. His only hope is to surpass himself, and not begin resting on his laurels too soon; perhaps it is never well, soon or late, to rest upon one's laurels. It is well for one to make one's self scarce, and the best way to do this is to be more and more jealous of perfection in one's work.

The editor's conditions are that having found a good thing he must get as much of it as he can, and the chances are that he will be less exacting than the contributor imagines. It is for the contributor to be exacting, and to let nothing go to the editor as long as there is the possibility of making it better. He need not be afraid of being forgotten because he does not keep sending; the editor's memory is simply relentless; he could not forget the writer who has pleased him if he would, for such writers are few.