0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orpheus Editions

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

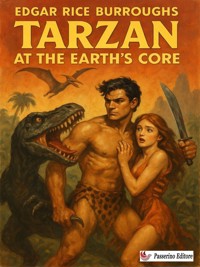

Edgar Rice Burroughs created the well-known character Tarzan, as well as John Carter, the adventurer of Mars.

The Gods of Mars is the second volume in the Barsoom Series, telling the adventures of John Carter, a confederate veteran of the American Civil War, who finds himself mysteriously transported to Mars, called Barsoom by its inhabitants.

On Barsoom, John Carter found love, but was transported back to Earth, unable to go back to Deja Thoris, the princess he fell in love with.

After ten years of separation from the love of his life, John Carter is sent back to Barsoom. But his arrival takes place in the worst possible location : the Valley Dor, which is the Barsoomian afterlife !

Will John Carter get out of this terrible place, and will he find again the princess he loves ?

You'll discover it in this second volume of the Barsoom Series.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

THE GODS OF MARS

by

Edgar Rice Burroughs

Orpheus Editions © 2020.

The cold hollow eye of a revolver sought the center of my forehead.

ANNOTATIONS

Born on the 1st of September 1875 in America, Edgar Rice Burroughs was a pulp fiction writer. He created the well-known character Tarzan, as well as John Carter, the adventurer of Mars. Burroughs is also the author of Pellucidar, a less known story about a fictional land situated into the hollow center of Earth.

Before becoming a writer, Burroughs occupied many jobs: soldier, cowboy, factory worker, manager of a mine owned by his brothers. After the failure of this mining company, Burroughs worked in railroad. He also worked as a pencil-sharpener wholesaler, and began writing fiction in 1911. Burroughs was an avid reader of pulp fiction magazines at this time, and considered the stories it contained of being of poor quality. He famously said later that he thought: « ...if people were paid for writing rot such as I read in some of those magazines, that I could write stories just as rotten. As a matter of fact, although I had never written a story, I knew absolutely that I could write stories just as entertaining and probably a whole lot more so than any I chanced to read in those magazines.

When the attack on Pearl Harbor occured, Burroughs, then in his late 60s, was in Honolulu. He applied to become a war correspondent, and became one of the oldest war correspondents during WWII. You can learn more about these events in the novel Don’t Go Near the Water, written by William Brinkley.

At the time of his death in 1950 (on March 19, 1950, from a heart attack), Edgar Rice Burroughs had written nearly 80 novels, and was the author who earned the most during his career from film adaptations of his stories. Indeed, the 27 Tarzan movies that were produced during his living were met with success at the box-office, and Burroughs was paid more than 2 million dollars in royalties.

His first story, Under the Moons of Mars, was published in serialized form in 1912, in the pulp magazine The All-Story. At this time, he used a pseudonym, Norman Bean. It launched the Barsoom series and was published in a book form in 1917, under the new title A Princess of Mars. At this time, the first three sequels of the Barsoom series were published as serials, and the first four Tarzan stories had been published as paperbacks.

Tarzan and the Barsoom series were met with success, and Burroughs notably started to exploit his Tarzan character in many media forms, such as a comic strip, merchandise, and movies. This was not frequent at the time, and many experts warned Burroughs of the risks of this practice, telling him that all of these media would just compete against each other and fail to generate money. The success of this endeavor proved the experts wrong, and Tarzan became a cultural icon.

Burroughs is considered to be an influential writer, and his Barsoom series influenced Scientifics and inspired them to explore Mars. An impact crater was then named in Burroughs honor after his death. Burroughs was inducted in 2003 into the Science-Fiction Hall of Fame.

FOREWORD

Twelve years had passed since I had laid the body of my great-uncle, Captain John Carter, of Virginia, away from the sight of men in that strange mausoleum in the old cemetery at Richmond.

Often had I pondered on the odd instructions he had left me governing the construction of his mighty tomb, and especially those parts which directed that he be laid in an OPEN casket and that the ponderous mechanism which controlled the bolts of the vault's huge door be accessible ONLY FROM THE INSIDE.

Twelve years had passed since I had read the remarkable manuscript of this remarkable man; this man who remembered no childhood and who could not even offer a vague guess as to his age; who was always young and yet who had dandled my grandfather's great-grandfather upon his knee; this man who had spent ten years upon the planet Mars; who had fought for the green men of Barsoom and fought against them; who had fought for and against the red men and who had won the ever beautiful Dejah Thoris, Princess of Helium, for his wife, and for nearly ten years had been a prince of the house of Tardos Mors, Jeddak of Helium.

Twelve years had passed since his body had been found upon the bluff before his cottage overlooking the Hudson, and oft-times during these long years I had wondered if John Carter were really dead, or if he again roamed the dead sea bottoms of that dying planet; if he had returned to Barsoom to find that he had opened the frowning portals of the mighty atmosphere plant in time to save the countless millions who were dying of asphyxiation on that far-gone day that had seen him hurtled ruthlessly through forty-eight million miles of space back to Earth once more. I had wondered if he had found his black-haired Princess and the slender son he had dreamed was with her in the royal gardens of Tardos Mors, awaiting his return.

Or, had he found that he had been too late, and thus gone back to a living death upon a dead world? Or was he really dead after all, never to return either to his mother Earth or his beloved Mars?

Thus was I lost in useless speculation one sultry August evening when old Ben, my body servant, handed me a telegram. Tearing it open I read:

'Meet me to-morrow hotel Raleigh Richmond. 'JOHN CARTER'

Early the next morning I took the first train for Richmond and within two hours was being ushered into the room occupied by John Carter.

As I entered he rose to greet me, his old-time cordial smile of welcome lighting his handsome face. Apparently he had not aged a minute, but was still the straight, clean-limbed fighting-man of thirty. His keen grey eyes were undimmed, and the only lines upon his face were the lines of iron character and determination that always had been there since first I remembered him, nearly thirty-five years before.

'Well, nephew,' he greeted me, 'do you feel as though you were seeing a ghost, or suffering from the effects of too many of Uncle Ben's juleps?'

'Juleps, I reckon,' I replied, 'for I certainly feel mighty good; but maybe it's just the sight of you again that affects me. You have been back to Mars? Tell me. And Dejah Thoris? You found her well and awaiting you?'

'Yes, I have been to Barsoom again, and—but it's a long story, too long to tell in the limited time I have before I must return. I have learned the secret, nephew, and I may traverse the trackless void at my will, coming and going between the countless planets as I list; but my heart is always in Barsoom, and while it is there in the keeping of my Martian Princess, I doubt that I shall ever again leave the dying world that is my life.

'I have come now because my affection for you prompted me to see you once more before you pass over for ever into that other life that I shall never know, and which though I have died thrice and shall die again to-night, as you know death, I am as unable to fathom as are you.

'Even the wise and mysterious therns of Barsoom, that ancient cult which for countless ages has been credited with holding the secret of life and death in their impregnable fastnesses upon the hither slopes of the Mountains of Otz, are as ignorant as we. I have proved it, though I near lost my life in the doing of it; but you shall read it all in the notes I have been making during the last three months that I have been back upon Earth.'

He patted a swelling portfolio that lay on the table at his elbow.

'I know that you are interested and that you believe, and I know that the world, too, is interested, though they will not believe for many years; yes, for many ages, since they cannot understand. Earth men have not yet progressed to a point where they can comprehend the things that I have written in those notes.

'Give them what you wish of it, what you think will not harm them, but do not feel aggrieved if they laugh at you.'

That night I walked down to the cemetery with him. At the door of his vault he turned and pressed my hand.

'Good-bye, nephew,' he said. 'I may never see you again, for I doubt that I can ever bring myself to leave my wife and boy while they live, and the span of life upon Barsoom is often more than a thousand years.'

He entered the vault. The great door swung slowly to. The ponderous bolts grated into place. The lock clicked. I have never seen Captain John Carter, of Virginia, since.

But here is the story of his return to Mars on that other occasion, as I have gleaned it from the great mass of notes which he left for me upon the table of his room in the hotel at Richmond.

There is much which I have left out; much which I have not dared to tell; but you will find the story of his second search for Dejah Thoris, Princess of Helium, even more remarkable than was his first manuscript which I gave to an unbelieving world a short time since and through which we followed the fighting Virginian across dead sea bottoms under the moons of Mars.

E. R. B.

CHAPTER I

THE PLANT MEN

As I stood upon the bluff before my cottage on that clear cold night in the early part of March, 1886, the noble Hudson flowing like the grey and silent spectre of a dead river below me, I felt again the strange, compelling influence of the mighty god of war, my beloved Mars, which for ten long and lonesome years I had implored with outstretched arms to carry me back to my lost love.

Not since that other March night in 1866, when I had stood without that Arizona cave in which my still and lifeless body lay wrapped in the similitude of earthly death had I felt the irresistible attraction of the god of my profession.

With arms outstretched toward the red eye of the great star I stood praying for a return of that strange power which twice had drawn me through the immensity of space, praying as I had prayed on a thousand nights before during the long ten years that I had waited and hoped.

Suddenly a qualm of nausea swept over me, my senses swam, my knees gave beneath me and I pitched headlong to the ground upon the very verge of the dizzy bluff.

Instantly my brain cleared and there swept back across the threshold of my memory the vivid picture of the horrors of that ghostly Arizona cave; again, as on that far-gone night, my muscles refused to respond to my will and again, as though even here upon the banks of the placid Hudson, I could hear the awful moans and rustling of the fearsome thing which had lurked and threatened me from the dark recesses of the cave, I made the same mighty and superhuman effort to break the bonds of the strange anaesthesia which held me, and again came the sharp click as of the sudden parting of a taut wire, and I stood naked and free beside the staring, lifeless thing that had so recently pulsed with the warm, red life-blood of John Carter.

With scarcely a parting glance I turned my eyes again toward Mars, lifted my hands toward his lurid rays, and waited.

Nor did I have long to wait; for scarce had I turned ere I shot with the rapidity of thought into the awful void before me. There was the same instant of unthinkable cold and utter darkness that I had experienced twenty years before, and then I opened my eyes in another world, beneath the burning rays of a hot sun, which beat through a tiny opening in the dome of the mighty forest in which I lay.

The scene that met my eyes was so un-Martian that my heart sprang to my throat as the sudden fear swept through me that I had been aimlessly tossed upon some strange planet by a cruel fate.

Why not? What guide had I through the trackless waste of interplanetary space? What assurance that I might not as well be hurtled to some far-distant star of another solar system, as to Mars?

I lay upon a close-cropped sward of red grasslike vegetation, and about me stretched a grove of strange and beautiful trees, covered with huge and gorgeous blossoms and filled with brilliant, voiceless birds. I call them birds since they were winged, but mortal eye ne'er rested on such odd, unearthly shapes.

The vegetation was similar to that which covers the lawns of the red Martians of the great waterways, but the trees and birds were unlike anything that I had ever seen upon Mars, and then through the further trees I could see that most un-Martian of all sights—an open sea, its blue waters shimmering beneath the brazen sun.

As I rose to investigate further I experienced the same ridiculous catastrophe that had met my first attempt to walk under Martian conditions. The lesser attraction of this smaller planet and the reduced air pressure of its greatly rarefied atmosphere, afforded so little resistance to my earthly muscles that the ordinary exertion of the mere act of rising sent me several feet into the air and precipitated me upon my face in the soft and brilliant grass of this strange world.

This experience, however, gave me some slightly increased assurance that, after all, I might indeed be in some, to me, unknown corner of Mars, and this was very possible since during my ten years' residence upon the planet I had explored but a comparatively tiny area of its vast expanse.

I arose again, laughing at my forgetfulness, and soon had mastered once more the art of attuning my earthly sinews to these changed conditions.

As I walked slowly down the imperceptible slope toward the sea I could not help but note the park-like appearance of the sward and trees. The grass was as close-cropped and carpet-like as some old English lawn and the trees themselves showed evidence of careful pruning to a uniform height of about fifteen feet from the ground, so that as one turned his glance in any direction the forest had the appearance at a little distance of a vast, high-ceiled chamber.

All these evidences of careful and systematic cultivation convinced me that I had been fortunate enough to make my entry into Mars on this second occasion through the domain of a civilized people and that when I should find them I would be accorded the courtesy and protection that my rank as a Prince of the house of Tardos Mors entitled me to.

The trees of the forest attracted my deep admiration as I proceeded toward the sea. Their great stems, some of them fully a hundred feet in diameter, attested their prodigious height, which I could only guess at, since at no point could I penetrate their dense foliage above me to more than sixty or eighty feet.

As far aloft as I could see the stems and branches and twigs were as smooth and as highly polished as the newest of American-made pianos. The wood of some of the trees was as black as ebony, while their nearest neighbours might perhaps gleam in the subdued light of the forest as clear and white as the finest china, or, again, they were azure, scarlet, yellow, or deepest purple.

And in the same way was the foliage as gay and variegated as the stems, while the blooms that clustered thick upon them may not be described in any earthly tongue, and indeed might challenge the language of the gods.

As I neared the confines of the forest I beheld before me and between the grove and the open sea, a broad expanse of meadow land, and as I was about to emerge from the shadows of the trees a sight met my eyes that banished all romantic and poetic reflection upon the beauties of the strange landscape.

To my left the sea extended as far as the eye could reach, before me only a vague, dim line indicated its further shore, while at my right a mighty river, broad, placid, and majestic, flowed between scarlet banks to empty into the quiet sea before me.

At a little distance up the river rose mighty perpendicular bluffs, from the very base of which the great river seemed to rise.

But it was not these inspiring and magnificent evidences of Nature's grandeur that took my immediate attention from the beauties of the forest. It was the sight of a score of figures moving slowly about the meadow near the bank of the mighty river.

Odd, grotesque shapes they were; unlike anything that I had ever seen upon Mars, and yet, at a distance, most manlike in appearance. The larger specimens appeared to be about ten or twelve feet in height when they stood erect, and to be proportioned as to torso and lower extremities precisely as is earthly man.

Their arms, however, were very short, and from where I stood seemed as though fashioned much after the manner of an elephant's trunk, in that they moved in sinuous and snakelike undulations, as though entirely without bony structure, or if there were bones it seemed that they must be vertebral in nature.

As I watched them from behind the stem of a huge tree, one of the creatures moved slowly in my direction, engaged in the occupation that seemed to be the principal business of each of them, and which consisted in running their oddly shaped hands over the surface of the sward, for what purpose I could not determine.

As he approached quite close to me I obtained an excellent view of him, and though I was later to become better acquainted with his kind, I may say that that single cursory examination of this awful travesty on Nature would have proved quite sufficient to my desires had I been a free agent. The fastest flier of the Heliumetic Navy could not quickly enough have carried me far from this hideous creature.

Its hairless body was a strange and ghoulish blue, except for a broad band of white which encircled its protruding, single eye: an eye that was all dead white—pupil, iris, and ball.

Its nose was a ragged, inflamed, circular hole in the centre of its blank face; a hole that resembled more closely nothing that I could think of other than a fresh bullet wound which has not yet commenced to bleed.

Below this repulsive orifice the face was quite blank to the chin, for the thing had no mouth that I could discover.

The head, with the exception of the face, was covered by a tangled mass of jet-black hair some eight or ten inches in length. Each hair was about the bigness of a large angleworm, and as the thing moved the muscles of its scalp this awful head-covering seemed to writhe and wriggle and crawl about the fearsome face as though indeed each separate hair was endowed with independent life.

The body and the legs were as symmetrically human as Nature could have fashioned them, and the feet, too, were human in shape, but of monstrous proportions. From heel to toe they were fully three feet long, and very flat and very broad.

As it came quite close to me I discovered that its strange movements, running its odd hands over the surface of the turf, were the result of its peculiar method of feeding, which consists in cropping off the tender vegetation with its razorlike talons and sucking it up from its two mouths, which lie one in the palm of each hand, through its arm-like throats.

In addition to the features which I have already described, the beast was equipped with a massive tail about six feet in length, quite round where it joined the body, but tapering to a flat, thin blade toward the end, which trailed at right angles to the ground.

By far the most remarkable feature of this most remarkable creature, however, were the two tiny replicas of it, each about six inches in length, which dangled, one on either side, from its armpits. They were suspended by a small stem which seemed to grow from the exact tops of their heads to where it connected them with the body of the adult.

Whether they were the young, or merely portions of a composite creature, I did not know.

As I had been scrutinizing this weird monstrosity the balance of the herd had fed quite close to me and I now saw that while many had the smaller specimens dangling from them, not all were thus equipped, and I further noted that the little ones varied in size from what appeared to be but tiny unopened buds an inch in diameter through various stages of development to the full-fledged and perfectly formed creature of ten to twelve inches in length.

Feeding with the herd were many of the little fellows not much larger than those which remained attached to their parents, and from the young of that size the herd graded up to the immense adults.

Fearsome-looking as they were, I did not know whether to fear them or not, for they did not seem to be particularly well equipped for fighting, and I was on the point of stepping from my hiding-place and revealing myself to them to note the effect upon them of the sight of a man when my rash resolve was, fortunately for me, nipped in the bud by a strange shrieking wail, which seemed to come from the direction of the bluffs at my right.

Naked and unarmed, as I was, my end would have been both speedy and horrible at the hands of these cruel creatures had I had time to put my resolve into execution, but at the moment of the shriek each member of the herd turned in the direction from which the sound seemed to come, and at the same instant every particular snake-like hair upon their heads rose stiffly perpendicular as if each had been a sentient organism looking or listening for the source or meaning of the wail. And indeed the latter proved to be the truth, for this strange growth upon the craniums of the plant men of Barsoom represents the thousand ears of these hideous creatures, the last remnant of the strange race which sprang from the original Tree of Life.

Instantly every eye turned toward one member of the herd, a large fellow who evidently was the leader. A strange purring sound issued from the mouth in the palm of one of his hands, and at the same time he started rapidly toward the bluff, followed by the entire herd.

Their speed and method of locomotion were both remarkable, springing as they did in great leaps of twenty or thirty feet, much after the manner of a kangaroo.

They were rapidly disappearing when it occurred to me to follow them, and so, hurling caution to the winds, I sprang across the meadow in their wake with leaps and bounds even more prodigious than their own, for the muscles of an athletic Earth man produce remarkable results when pitted against the lesser gravity and air pressure of Mars.

Their way led directly towards the apparent source of the river at the base of the cliffs, and as I neared this point I found the meadow dotted with huge boulders that the ravages of time had evidently dislodged from the towering crags above.

For this reason I came quite close to the cause of the disturbance before the scene broke upon my horrified gaze. As I topped a great boulder I saw the herd of plant men surrounding a little group of perhaps five or six green men and women of Barsoom.

That I was indeed upon Mars I now had no doubt, for here were members of the wild hordes that people the dead sea bottoms and deserted cities of that dying planet.

Here were the great males towering in all the majesty of their imposing height; here were the gleaming white tusks protruding from their massive lower jaws to a point near the centre of their foreheads, the laterally placed, protruding eyes with which they could look forward or backward, or to either side without turning their heads, here the strange antennae-like ears rising from the tops of their foreheads; and the additional pair of arms extending from midway between the shoulders and the hips.

Even without the glossy green hide and the metal ornaments which denoted the tribes to which they belonged, I would have known them on the instant for what they were, for where else in all the universe is their like duplicated?

There were two men and four females in the party and their ornaments denoted them as members of different hordes, a fact which tended to puzzle me infinitely, since the various hordes of green men of Barsoom are eternally at deadly war with one another, and never, except on that single historic instance when the great Tars Tarkas of Thark gathered a hundred and fifty thousand green warriors from several hordes to march upon the doomed city of Zodanga to rescue Dejah Thoris, Princess of Helium, from the clutches of Than Kosis, had I seen green Martians of different hordes associated in other than mortal combat.

But now they stood back to back, facing, in wide-eyed amazement, the very evidently hostile demonstrations of a common enemy.

Both men and women were armed with long-swords and daggers, but no firearms were in evidence, else it had been short shrift for the gruesome plant men of Barsoom.

Presently the leader of the plant men charged the little party, and his method of attack was as remarkable as it was effective, and by its very strangeness was the more potent, since in the science of the green warriors there was no defence for this singular manner of attack, the like of which it soon was evident to me they were as unfamiliar with as they were with the monstrosities which confronted them.

The plant man charged to within a dozen feet of the party and then, with a bound, rose as though to pass directly above their heads. His powerful tail was raised high to one side, and as he passed close above them he brought it down in one terrific sweep that crushed a green warrior's skull as though it had been an eggshell.

The balance of the frightful herd was now circling rapidly and with bewildering speed about the little knot of victims. Their prodigious bounds and the shrill, screeching purr of their uncanny mouths were well calculated to confuse and terrorize their prey, so that as two of them leaped simultaneously from either side, the mighty sweep of those awful tails met with no resistance and two more green Martians went down to an ignoble death.

There were now but one warrior and two females left, and it seemed that it could be but a matter of seconds ere these, also, lay dead upon the scarlet sward.

But as two more of the plant men charged, the warrior, who was now prepared by the experiences of the past few minutes, swung his mighty long-sword aloft and met the hurtling bulk with a clean cut that clove one of the plant men from chin to groin.

The other, however, dealt a single blow with his cruel tail that laid both of the females crushed corpses upon the ground.

As the green warrior saw the last of his companions go down and at the same time perceived that the entire herd was charging him in a body, he rushed boldly to meet them, swinging his long-sword in the terrific manner that I had so often seen the men of his kind wield it in their ferocious and almost continual warfare among their own race.

Cutting and hewing to right and left, he laid an open path straight through the advancing plant men, and then commenced a mad race for the forest, in the shelter of which he evidently hoped that he might find a haven of refuge.

He had turned for that portion of the forest which abutted on the cliffs, and thus the mad race was taking the entire party farther and farther from the boulder where I lay concealed.

As I had watched the noble fight which the great warrior had put up against such enormous odds my heart had swelled in admiration for him, and acting as I am wont to do, more upon impulse than after mature deliberation, I instantly sprang from my sheltering rock and bounded quickly toward the bodies of the dead green Martians, a well-defined plan of action already formed.

Half a dozen great leaps brought me to the spot, and another instant saw me again in my stride in quick pursuit of the hideous monsters that were rapidly gaining on the fleeing warrior, but this time I grasped a mighty long-sword in my hand and in my heart was the old blood lust of the fighting man, and a red mist swam before my eyes and I felt my lips respond to my heart in the old smile that has ever marked me in the midst of the joy of battle.

Swift as I was I was none too soon, for the green warrior had been overtaken ere he had made half the distance to the forest, and now he stood with his back to a boulder, while the herd, temporarily balked, hissed and screeched about him.

With their single eyes in the centre of their heads and every eye turned upon their prey, they did not note my soundless approach, so that I was upon them with my great long-sword and four of them lay dead ere they knew that I was among them.

For an instant they recoiled before my terrific onslaught, and in that instant the green warrior rose to the occasion and, springing to my side, laid to the right and left of him as I had never seen but one other warrior do, with great circling strokes that formed a figure eight about him and that never stopped until none stood living to oppose him, his keen blade passing through flesh and bone and metal as though each had been alike thin air.

As we bent to the slaughter, far above us rose that shrill, weird cry which I had heard once before, and which had called the herd to the attack upon their victims. Again and again it rose, but we were too much engaged with the fierce and powerful creatures about us to attempt to search out even with our eyes the author of the horrid notes.

Great tails lashed in frenzied anger about us, razor-like talons cut our limbs and bodies, and a green and sticky syrup, such as oozes from a crushed caterpillar, smeared us from head to foot, for every cut and thrust of our longswords brought spurts of this stuff upon us from the severed arteries of the plant men, through which it courses in its sluggish viscidity in lieu of blood.

Once I felt the great weight of one of the monsters upon my back and as keen talons sank into my flesh I experienced the frightful sensation of moist lips sucking the lifeblood from the wounds to which the claws still clung.

I was very much engaged with a ferocious fellow who was endeavouring to reach my throat from in front, while two more, one on either side, were lashing viciously at me with their tails.

The green warrior was much put to it to hold his own, and I felt that the unequal struggle could last but a moment longer when the huge fellow discovered my plight, and tearing himself from those that surrounded him, he raked the assailant from my back with a single sweep of his blade, and thus relieved I had little difficulty with the others.

Once together, we stood almost back to back against the great boulder, and thus the creatures were prevented from soaring above us to deliver their deadly blows, and as we were easily their match while they remained upon the ground, we were making great headway in dispatching what remained of them when our attention was again attracted by the shrill wail of the caller above our heads.

This time I glanced up, and far above us upon a little natural balcony on the face of the cliff stood a strange figure of a man shrieking out his shrill signal, the while he waved one hand in the direction of the river's mouth as though beckoning to some one there, and with the other pointed and gesticulated toward us.

A glance in the direction toward which he was looking was sufficient to apprise me of his aims and at the same time to fill me with the dread of dire apprehension, for, streaming in from all directions across the meadow, from out of the forest, and from the far distance of the flat land across the river, I could see converging upon us a hundred different lines of wildly leaping creatures such as we were now engaged with, and with them some strange new monsters which ran with great swiftness, now erect and now upon all fours.

"It will be a great death," I said to my companion. "Look!"

As he shot a quick glance in the direction I indicated he smiled.

"We may at least die fighting and as great warriors should, John Carter," he replied.

We had just finished the last of our immediate antagonists as he spoke, and I turned in surprised wonderment at the sound of my name.

And there before my astonished eyes I beheld the greatest of the green men of Barsoom; their shrewdest statesman, their mightiest general, my great and good friend, Tars Tarkas, Jeddak of Thark.

CHAPTER II

A FOREST BATTLE

Tars Tarkas and I found no time for an exchange of experiences as we stood there before the great boulder surrounded by the corpses of our grotesque assailants, for from all directions down the broad valley was streaming a perfect torrent of terrifying creatures in response to the weird call of the strange figure far above us.

"Come," cried Tars Tarkas, "we must make for the cliffs. There lies our only hope of even temporary escape; there we may find a cave or a narrow ledge which two may defend for ever against this motley, unarmed horde."

Together we raced across the scarlet sward, I timing my speed that I might not outdistance my slower companion. We had, perhaps, three hundred yards to cover between our boulder and the cliffs, and then to search out a suitable shelter for our stand against the terrifying things that were pursuing us.

They were rapidly overhauling us when Tars Tarkas cried to me to hasten ahead and discover, if possible, the sanctuary we sought. The suggestion was a good one, for thus many valuable minutes might be saved to us, and, throwing every ounce of my earthly muscles into the effort, I cleared the remaining distance between myself and the cliffs in great leaps and bounds that put me at their base in a moment.

The cliffs rose perpendicular directly from the almost level sward of the valley. There was no accumulation of fallen debris, forming a more or less rough ascent to them, as is the case with nearly all other cliffs I have ever seen. The scattered boulders that had fallen from above and lay upon or partly buried in the turf, were the only indication that any disintegration of the massive, towering pile of rocks ever had taken place.

My first cursory inspection of the face of the cliffs filled my heart with forebodings, since nowhere could I discern, except where the weird herald stood still shrieking his shrill summons, the faintest indication of even a bare foothold upon the lofty escarpment.

To my right the bottom of the cliff was lost in the dense foliage of the forest, which terminated at its very foot, rearing its gorgeous foliage fully a thousand feet against its stern and forbidding neighbour.

To the left the cliff ran, apparently unbroken, across the head of the broad valley, to be lost in the outlines of what appeared to be a range of mighty mountains that skirted and confined the valley in every direction.

Perhaps a thousand feet from me the river broke, as it seemed, directly from the base of the cliffs, and as there seemed not the remotest chance for escape in that direction I turned my attention again toward the forest.

The cliffs towered above me a good five thousand feet. The sun was not quite upon them and they loomed a dull yellow in their own shade. Here and there they were broken with streaks and patches of dusky red, green, and occasional areas of white quartz.

Altogether they were very beautiful, but I fear that I did not regard them with a particularly appreciative eye on this, my first inspection of them.

Just then I was absorbed in them only as a medium of escape, and so, as my gaze ran quickly, time and again, over their vast expanse in search of some cranny or crevice, I came suddenly to loathe them as the prisoner must loathe the cruel and impregnable walls of his dungeon.

Tars Tarkas was approaching me rapidly, and still more rapidly came the awful horde at his heels.

It seemed the forest now or nothing, and I was just on the point of motioning Tars Tarkas to follow me in that direction when the sun passed the cliff's zenith, and as the bright rays touched the dull surface it burst out into a million scintillant lights of burnished gold, of flaming red, of soft greens, and gleaming whites—a more gorgeous and inspiring spectacle human eye has never rested upon.

The face of the entire cliff was, as later inspection conclusively proved, so shot with veins and patches of solid gold as to quite present the appearance of a solid wall of that precious metal except where it was broken by outcroppings of ruby, emerald, and diamond boulders—a faint and alluring indication of the vast and unguessable riches which lay deeply buried behind the magnificent surface.

But what caught my most interested attention at the moment that the sun's rays set the cliff's face a-shimmer, was the several black spots which now appeared quite plainly in evidence high across the gorgeous wall close to the forest's top, and extending apparently below and behind the branches.

Almost immediately I recognised them for what they were, the dark openings of caves entering the solid walls—possible avenues of escape or temporary shelter, could we but reach them.

There was but a single way, and that led through the mighty, towering trees upon our right. That I could scale them I knew full well, but Tars Tarkas, with his mighty bulk and enormous weight, would find it a task possibly quite beyond his prowess or his skill, for Martians are at best but poor climbers. Upon the entire surface of that ancient planet I never before had seen a hill or mountain that exceeded four thousand feet in height above the dead sea bottoms, and as the ascent was usually gradual, nearly to their summits they presented but few opportunities for the practice of climbing. Nor would the Martians have embraced even such opportunities as might present themselves, for they could always find a circuitous route about the base of any eminence, and these roads they preferred and followed in preference to the shorter but more arduous ways.

However, there was nothing else to consider than an attempt to scale the trees contiguous to the cliff in an effort to reach the caves above.

The Thark grasped the possibilities and the difficulties of the plan at once, but there was no alternative, and so we set out rapidly for the trees nearest the cliff.