Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

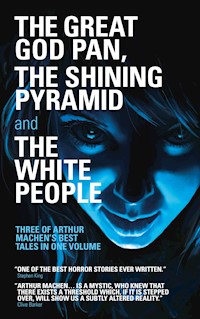

An experiment into the sources of the human brain through the mind of a young woman has gone horribly wrong. She has seen the great god Pan and will die giving birth to a daughter. Twenty years later feted society hostess Helen Vaughan becomes the source of much fevered speculation. Many men are infatuated with her beauty, but great beauty has a price, sometimes you have to pay with the only thing you have left. The Great God Pan was a sensation when first published in 1894. Its author, Arthur Machen, was a struggling unknown writer living in London. He had translated Casanova's memoirs and was living on a small inheritance. He immediately became one of the most talked-about writers of the last years of the nineteenth century, while the publication marked the start of his ongoing influence on modern fantasy and horror. Machen's dark imaginings of the reality behind ancient beliefs feature again in the acclaimed, mesmerising short story 'The White People' and the curious tale 'The Shining Pyramid', also in this volume.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 297

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Title PageAbout Arthur MachenForeword: Rending the VeilTHE GREAT GOD PANI. The ExperimentII. Mr Clarke’s MemoirsIII. The City of ResurrectionsIV. The Discovery in Paul StreetV. The Letter of AdviceVI. The SuicidesVII. The Encounter in SohoVIII. The FragmentsTHE SHINING PYRAMIDI. The Arrowhead CharacterII. The Eyes on the WallIII. The Search for the BowlIV. The Secret of the PyramidV. The Little PeopleTHE WHITE PEOPLEPrologueThe Green BookEpilogueNotes on the text 1Notes on the text 2Foreword by Ramsey CampbellThe Friends of Arthur MachenLibrary of WalesCopyright

THE GREAT GOD PAN

THE SHINING PYRAMID

THE WHITE PEOPLE

Arthur Machen

LIBRARY OF WALES

Arthur Machen wasborn in 1863 in Caerleon, Gwent. His father, vicar of the small parish of Llanddewi Fach, was unable to fund Machen’s full education and withdrew his son from Hereford Cathedral School, effectively ending his chances of university and ordination. Instead, Machen moved to London with hopes of a literary career, sparked by his private publication of 100 copies of the long poem ‘Eleusinia’. He took up a variety of writing commissions including translatingThe Memoirs of Jacques Casanova, as well as cataloguing an enormous body of works on the occult. His first authored book,The Anatomy of Tobacco, was published in 1884, but it was in the 1890s that Machen achieved literary success and a reputation as a leading author of gothic texts. In this decade he publishedThe Great God Pan,‘The Shining Pyramid’ andThe Three Impostors, but also wrote several of his most famous works, includingThe Hill of Dreams, ‘The White People’ and ‘The Secret Glory’. Machen gained widespread notoriety in 1914 with the publication of his story ‘The Bowmen’, describing the spectral appearance of the bowmen of Agincourt in the trenches of the First World War.

Machen’s work bears the imprint of the Welsh border country of his upbringing, and his native Caerleon, with its links to both Roman history and the myth of King Arthur’s Round Table; the occult and gothic works of thefin de siècle; his self-avowed ‘Celtic’ identity; and literary London. He published three volumes of autobiography:Far Off Things(1922),Things Near and Far(1923) andThe London Adventure(1924). Arthur Machen died in 1947 aged 84; and maintains a loyal and international following to this day.

FOREWORD

Rending the Veil

‘I translated awe, at worst awfulness, into evil; again, I say, one dreams in fire and works in clay.’ So wrote Arthur Machen in his autobiographyFar Off Thingsabout his first published story,The Great God Pan. Some of the greatest tales of supernatural terror are born of the ambition to convey awe, and this shines through in the best of Machen’s work. Do all writers with a vision have to feel they’ve failed? The sense of falling short may be a necessary element of any worthwhile writer’s life. There’s no evidence that Machen ever knew how influential he would be, butThe Great God Panis crucial to the development of horror literature. Peter Straub’sGhost Storywas written as a tribute, and centres on a female monster as seductive as Machen’s, while M. John Harrison actually calls his highly personal reworkingThe Great God Pan. H.P. Lovecraft gave Machen’s story an entire appreciative page in hisSupernatural Horror in Literature, and seems to have applied a version of its structure to his taleThe Call of Cthulhu. Lovecraft’s colleague, Frank Belknap Long, wrote a sonnet, ‘On Reading Arthur Machen’, and incorporated Machenesque elements into his storyThe Space-Eaters, more enthusiastically than expertly. Most recently, Stephen King’s storyNemulates its form while addressing its essential theme; even the title echoes Machen (a different tale of his). More than one hundred years after its first appearance, the power of ‘Pan’ seems as potent as ever.

It’s easier to savour than it is to analyse. Machen’s method seems to be the utter opposite of Poe’s, for instance. Whereas Poe organises all the elements of a tale to achieve a concerted effect, Machen lets the reader piece the narrative together by gathering fragments, disconcertingly varied in their tone. In this he remains modern; shifts of tone within the tale of terror are far commoner now. If at times the language of the text seems lighter than the material would warrant, it’s always overtaken by outbursts of lyricism, or awe, or horror. I would argue that the form is expressing the content – the central theme of the eternal mysteries that are veiled by the mundane and infrequently show through. Whenever Machen writes of evil, his prose sings no less melodiously than when he is attempting to convey the numinous. A passage from the story – ‘I listened to her as she spoke in her beautiful voice, spoke of things which even now I would not dare whisper in blackest night, though I stood in the midst of a wilderness’ – might almost epitomise the tale itself. Indeed, whispering comes into it, and hints at an eroticism that the modern reader might find even more questionable than the Victorian audience did. If this is one reason why the story retains its ability to disturb, I believe that the true source of its power lies in its mystery. Its mosaic narrative becomes a metaphor for something larger than is shown, and even when characters offer explanations, these never quite encompass the secret it keeps. Enigmas can be more satisfying and more lasting than any explanation, and this is nowhere truer than in the tale of supernatural terror.

The Great God Panwas not well received when it was published, in the yellow eighteen-nineties. ‘We fail to see why such absurdities should be presented to intelligent readers…’ ‘…a failure and an absurdity…’ ‘…to shock would seem to have been Mr Machen’s sole intention…’ ‘…lurid and nonsensical…’ ‘…gruesome, ghastly, and dull…’ Machen amused himself by assembling these and many other hostile reviews in a collection:Precious Balms.Such comments – often virtually indistinguishable from these – have always dogged the field.

1895 saw the publication ofThe Shining Pyramid, which develops Machen’s notion of the legend that stands for a darker truth. The investigator Dyson could be a colleague or admirer of Sherlock Holmes, but his detection leads away from rationality rather than taking the Baker Street route. It ends with his account of the events we’ve witnessed, a device that isn’t quite as generic as it sounds. His speech seems oddly incantatory, and the elucidation leaves the terror intact, somewhat as Le Fanu’s Dr Hesselius (inGreen Tea,Carmillaand other cases viewed through a glass darkly) never fully explains away the supernatural. Of course Dyson is speaking for Machen, and who is to say which of them is more possessed by a vision? The spellbound voice that keeps breaking through the analytical narrative finds its fullest expression in two later tales.The Hill of Dreams(first published in 1904, seven years after it was completed) often veers close to autobiography, certainly in its protagonist’s mysticism, although it also touches on terror. The Library of Wales will revive it as a companion volume to this one.The White Peoplewas written in 1899 but waited five years to be published. While its later traces are less obviously discernible than those ofPan, it certainly influenced T. E. D. Klein’s fine novelThe Ceremonies. It takes the form of an illustrated lecture on Machen’s crucial theme: ‘Sorcery and sanctity, they are the only realities’ – but what an illustration! Like all good art, it has to be experienced, not read in any kind of summary. Where some of Machen’s earlier stories peer behind the veils of fairy tales and folk traditions, the central text ofThe White Peopleoften takes the form of one. Sometimes it adopts the rhythms of a ballad, and much of it could be called poetry, while as a whole the entranced narrative seems to prefigure developments by Joyce and Virginia Woolf. I can think of no other tale of terror that employs the naïve voice so deftly or to such profound effect. It raises Poe’s device of the unreliable narrator to new heights of refinement. It suggests the occult experiences and transformation of the young protagonist with consummate subtlety, and the tension between what is communicated and the tone of the communication is itself a source of wonder and disquiet. The childish voice can be an especially poignant way of narrating a tale of terror, but few if any have achieved such delicacy of dread.

Even the explanation that rounds off the tale preserves a hushed sense of mystery. I hope I haven’t reduced this with all these attempts to convey my enthusiasm, but the tale has survived worse comments than mine, if not clumsier. ‘Mr Arthur Machen can scarcely be said to have made literature…’ ‘…well-nigh soporific…’ ‘…the half-mad imaginings of a degenerate mind steeped in morbidity…’ ‘…he has not the power of creating horror…’ All these appear inPrecious Balms, along with ‘Mr Arthur Machen’s stories fail to thrill us, because the artificial horrors… have practically no correspondence with the sins and horrors of real life.’ It’s a perennial objection to the genre, and a false one – the argument that horror fiction has to be tethered to reality, a criticism seldom aimed at tragedy or comedy. It’s especially inappropriate to Machen, who raises horror to the heights.

Twenty years ago, in an essay on the field, the literary critic David Aylward wrote ‘Writers [of supernatural fiction], who used to strive for awe and achieve fear, now strive for fear and achieve only disgust.’ Alas, they have been superseded by a generation of writers who compete for mere disgust. Some still look to the masters, however, and none of those strove to reach higher than Machen. His critics are ashes, but his light shines as brightly as ever, illuminating visions as disturbing as they are uncommon and timeless. I’m delighted that the Library of Wales has brought them back into the world.

Ramsey Campbell

THEGREAT GOD PAN

I

The Experiment

‘I am glad you came, Clarke; very glad indeed. I was not sure you could spare the time.’

‘I was able to make arrangements for a few days; things are not very lively just now. But have you no misgivings, Raymond? Is it absolutely safe?’

The two men were slowly pacing the terrace in front of Dr Raymond’s house. The sun still hung above the western mountain line, but it shone with a dull red glow that cast no shadows, and all the air was quiet; a sweet breath came from the great wood on the hillside above, and with it, at intervals, the soft murmuring call of the wild doves. Below, in the long lovely valley, the river wound in and out between the lonely hills, and, as the sun hovered and vanished into the west, a faint mist, pure white, began to rise from the banks1. Dr Raymond turned sharply to his friend.

‘Safe? Of course it is. In itself the operation is a perfectly simple one; any surgeon could do it.’

‘And there is no danger at any other stage?’

‘None; absolutely no physical danger whatever, I give you my word. You were always timid, Clarke, always; but you know my history. I have devoted myself to transcendental medicine for the last twenty years. I have heard myself called quack and charlatan and impostor, but all the while I knew I was on the right path. Five years ago I reached the goal, and since then every day has been a preparation for what we shall do tonight.’

‘I should like to believe it is all true.’ Clarke knit his brows, and looked doubtfully at Dr Raymond. ‘Are you perfectly sure, Raymond, that your theory is not a phantasmagoria – a splendid vision, certainly, but a mere vision after all?’

Dr Raymond stopped in his walk and turned sharply. He was a middle-aged man, gaunt and thin, of a pale yellow complexion, but as he answered Clarke and faced him, there was a flush on his cheek.

‘Look about you, Clarke. You see the mountain, and hill following after hill, as wave on wave, you see the woods and orchards, the fields of ripe corn, and the meadows reaching to the reed beds by the river. You see me standing here beside you, and hear my voice; but I tell you that all these things – yes, from that star that has just shone out in the sky to the solid ground beneath our feet – I say that all these are but dreams and shadows; the shadows that hide the real world from our eyes. Thereisa real world, but it is beyond this glamour and this vision, beyond these ‘chases in Arras, dreams in a career’2, beyond them all as beyond a veil. I do not know whether any human being has ever lifted that veil; but I do know, Clarke, that you and I shall see it lifted this very night from before another’s eyes. You may think all this strange nonsense; it may be strange, but it is true, and the ancients knew what lifting the veil means. They called it seeing the god Pan3.’

Clarke shivered; the white mist gathering over the river was chilly.

‘It is wonderful indeed,’ he said. ‘We are standing on the brink of a strange world, Raymond, if what you say is true. I suppose the knife is absolutely necessary?’

‘Yes; a slight lesion in the grey matter, that is all; a trifling rearrangement of certain cells, a microscopical alteration that would escape the attention of ninety-nine brain specialists out of a hundred. I don’t want to bother you with ‘shop’, Clarke; I might give you a mass of technical detail which would sound very imposing, and would leave you as enlightened as you are now. But I suppose you have read, casually, in out-of-the-way corners of your paper, that immense strides have been made recently in the physiology of the brain. I saw a paragraph the other day about Digby’s theory, and Browne Faber’s discoveries. Theories and discoveries! Where they are standing now, I stood fifteen years ago, and I need not tell you that I have not been standing still for the last fifteen years. It will be enough if I say that five years ago I made the discovery to which I alluded when I said that then I reached the goal. After years of labour, after years of toiling and groping in the dark, after days and nights of disappointment and sometimes of despair, in which I used now and then to tremble and grow cold with the thought that perhaps there were others seeking for what I sought, at last, after so long, a pang of sudden joy thrilled my soul, and I knew the long journey was at an end. By what seemed then and still seems a chance, the suggestion of a moment’s idle thought followed up upon familiar lines and paths that I had tracked a hundred times already, the great truth burst upon me, and I saw, mapped out in lines of sight, a whole world, a sphere unknown; continents and islands, and great oceans in which no ship has sailed (to my belief) since a Man first lifted up his eyes and beheld the sun, and the stars of heaven, and the quiet earth beneath. You will think all this highflown language, Clarke, but it is hard to be literal. And yet; I do not know whether what I am hinting at cannot be set forth in plain and homely terms. For instance, this world of ours is pretty well girded now4with the telegraph wires and cables; thought, with something less than the speed of thought, flashes from sunrise to sunset, from north to south, across the floods and the desert places. Suppose that an electrician of today were suddenly to perceive that he and his friends have merely been playing with pebbles and mistaking them for the foundations of the world; suppose that such a man saw uttermost space lie open before the current, the words of men flash forth to the sun and beyond the sun into the systems beyond, and the voices of articulate-speaking men echo in the waste void that bounds our thought. As analogies go, that is a pretty good analogy of what I have done; you can understand now a little of what I felt as I stood here one evening; it was a summer evening, and the valley looked much as it does now; I stood here, and saw before me the unutterable, the unthinkable gulf that yawns profound between two worlds, the world of matter and the world of spirit; I saw the great empty deep stretch dim before me, and in that instant a bridge of light leapt from the earth to the unknown shore, and the abyss was spanned. You may look in Browne Faber’s book, if you like, and you will find that to the present day men of science are unable to account for the presence, or to specify the functions, of a certain group of nerve cells in the brain. That group is, as it were, land to let, a mere waste place for fanciful theories. I am not in the position of Browne Faber and the specialists, I am perfectly instructed as to the possible functions of those nerve-centres in the scheme of things. With a touch I can bring them into play, with a touch, I say, I can set free the current, with a touch I can complete the communication between this world of sense and – we shall be able to finish the sentence later on. Yes, the knife is necessary; but think what that knife will effect. It will level utterly the solid wall of sense, and probably, for the first time since man was made, a spirit will gaze on a spirit world. Clarke, Mary will see the god Pan!’

‘But you remember what you wrote to me? I thought it would be requisite that she…’

He whispered the rest into the doctor’s ear.

‘Not at all, not at all. That is nonsense. I assure you.

Indeed, it is better as it is; I am quite certain of that.’ ‘Consider the matter well, Raymond. It’s a great responsibility. Something might go wrong; you would be a miserable man for the rest of your days.’

‘No, I think not, even if the worst happened. As you know, I rescued Mary from the gutter, and from almost certain starvation, when she was a child; I think her life is mine, to use as I see fit. Come, it’s getting late; we had better go in.’

Dr Raymond led the way into the house, through the hall, and down a long dark passage. He took a key from his pocket and opened a heavy door, and motioned Clarke into his laboratory. It had once been a billiard room, and was lighted by a glass dome in the centre of the ceiling, whence there still shone a sad grey light on the figure of the doctor as he lit a lamp with a heavy shade and placed it on a table in the middle of the room.

Clarke looked about him. Scarcely a foot of wall remained bare; there were shelves all around laden with bottles and phials of all shapes and colours, and at one end stood a little Chippendale bookcase. Raymond pointed to this.

‘You see that parchment Oswald Crollius5?He was one of the first to show me the way, though I don’t think he ever found it himself. That is a strange saying of his: “In every grain of wheat there lies hidden the soul of a star.”’

There was not much furniture in the laboratory. The table in the centre, a stone slab with a drain in one corner, the two armchairs on which Raymond and Clarke were sitting; that was all, except an odd-looking chair at the end of the room. Clarke looked at it, and raised his eyebrows.

‘Yes, that is the chair,’ said Raymond. ‘We may as well place it in position.’ He got up and wheeled the chair to the light, and began raising and lowering it, letting down the seat, setting the back at various angles, and adjusting the foot-rest. It looked comfortable enough, and Clarke passed his hand over the soft green velvet, as the doctor manipulated the levers.

‘Now, Clarke, make yourself quite comfortable. I have a couple hours’ work before me; I was obliged to leave certain matters to the last.’

Raymond went to the stone slab, and Clarke watched him drearily as he bent over a row of phials and lit the flame under the crucible. The doctor had a small hand-lamp, shaded as the larger one, on a ledge above his apparatus, and Clarke, who sat in the shadows, looked down the great dreary room, wondering at the bizarre effects of brilliant light and undefined darkness contrasting with one another. Soon he became conscious of an odd odour, at first the merest suggestion of odour in the room; and as it grew more decided he felt surprised that he was not reminded of the chemist’s shop or the surgery. Clarke found himself idly endeavouring to analyse the sensation, and, half conscious, he began to think of a day, fifteen years ago, that he had spent roaming through the woods and meadows near his old home. It was a burning day at the beginning of August, the heat had dimmed the outlines of all things and all distances with a faint mist, and people who observed the thermometer spoke of an abnormal register, of a temperature that was almost tropical. Strangely that wonderful hot day of the ’fifties rose up in Clarke’s imagination; the sense of dazzling, all-pervading sunlight seemed to blot out the shadows and the lights of the laboratory, and he felt again the heated air beating in gusts about his face, saw the shimmer rising from the turf, and heard the myriad murmur of the summer.

‘I hope the smell doesn’t annoy you, Clarke; there’s nothing unwholesome about it. It may make you a bit sleepy, that’s all.’

Clarke heard the words quite distinctly, and knew that Raymond was speaking to him, but for the life of him he could not rouse himself from his lethargy. He could only think of the lonely walk he had taken fifteen years ago; it was his last look at the fields and woods he had known since he was a child, and now it all stood out in brilliant light, as a picture, before him. Above all there came to his nostrils the scent of summer, the smell of flowers mingled, and the odour of the woods, of cool shaded places, deep in the green depths, drawn forth by the sun’s heat; and the scent of the good earth, lying as it were with arms stretched forth, and smiling lips, overpowered all. His fancies made him wander, as he had wandered long ago, from the fields into the wood, tracking a little path between the shining undergrowth of beech trees; and the trickle of water dropping from the limestone rock sounded as a clear melody in the dream. Thoughts began to go astray and to mingle with other recollections; the beech alley was transformed to a path between ilex trees, and here and there a vine climbed from bough to bough, and sent up waving tendrils and drooped with purple grapes, and the sparse grey-green leaves of a wild olive tree stood out against the dark shadows of the ilex. Clarke, in the deep folds of dream, was conscious that the path from his father’s house had led him into an undiscovered country, and he was wondering at the strangeness of it all, when suddenly, in place of the hum and murmur of the summer, an infinite silence seemed to fall on all things, and the wood was hushed, and for a moment of time he stood face to face there with a presence, that was neither man nor beast, neither living nor dead, but all things mingled, the form of all things but devoid of all form. And in that moment, the sacrament of body and soul was dissolved, and a voice seemed to cry ‘Let us go hence,’ and then the darkness of darkness beyond the stars, the darkness of everlasting.

When Clarke woke up with a start he saw Raymond pouring a few drops of some oily fluid into a green phial, which he stoppered tightly.

‘You have been dozing,’ he said; ‘the journey must have tired you out. It is done now. I am going to fetch Mary; I shall be back in ten minutes.’

Clarke lay back in his chair and wondered. It seemed as if he had but passed from one dream into another. He half expected to see the walls of the laboratory melt and disappear, and to awake in London, shuddering at his own sleeping fancies. But at last the door opened, and the doctor returned, and behind him came a girl of about seventeen, dressed all in white. She was so beautiful that Clarke did not wonder at what the doctor had written to him. She was blushing now over face and neck and arms, but Raymond seemed unmoved.

‘Mary,’ he said, ‘the time has come. You are quite free. Are you willing to trust yourself to me entirely?’

‘Yes, dear.’

‘You hear that, Clarke? You are my witness. Here is the chair, Mary. It is quite easy. Just sit in it and lean back. Are you ready?’

‘Yes, dear, quite ready. Give me a kiss before you begin.’

The doctor stooped and kissed her mouth, kindly enough. ‘Now shut your eyes,’ he said. The girl closed her eyelids, as if she were tired, as if she longed for sleep, and Raymond held the green phial to her nostrils. Her face grew white, whiter than her dress; she struggled faintly, and then, with the feeling of submission strong within her, crossed her arms upon her breast as a little child about to say her prayers. The bright light of the lamp beat full upon her, and Clarke watched changes fleeting over that face as the changes of the hills when the summer clouds float across the sun. And then she lay all white and still, and the doctor turned up one of her eyelids. She was quite unconscious. Raymond pressed hard on one of the levers and the chair instantly sank back. Clarke saw him cutting away a circle, like a tonsure, from her hair, and the lamp was moved nearer. Raymond took a small glittering instrument from a little case, and Clarke turned away shuddering. When he looked again the doctor was binding up the wound he had made.

‘She will awake in five minutes.’ Raymond was still perfectly cool. ‘There is nothing more to be done; we can only wait.’

The minutes passed slowly; they could hear a slow, heavy ticking. There was an old clock in the passage. Clarke felt sick and faint; his knees shook beneath him, he could hardly stand.

Suddenly, as they watched, they heard a long-drawn sigh, and suddenly did the colour that had vanished return to the girl’s cheeks, and suddenly her eyes opened. Clarke quailed before them. They shone with an awful light, looking far away, and a great wonder fell upon her face, and her hands stretched out as if to touch what was invisible; but in an instant the wonder faded, and gave place to the most awful terror. The muscles of her face were hideously convulsed, she shook from head to foot; the soul seemed struggling and shuddering within the house of flesh. It was a horrible sight, and Clarke rushed forward, as she fell shrieking to the floor.

Three days later Raymond took Clarke to Mary’s bedside. She was lying wide awake, rolling her head from side to side, and grinning vacantly.

‘Yes,’ said the doctor, still quite cool, ‘it is a great pity; she is a hopeless idiot. However, it could not be helped; and, after all, she has seen the great god Pan.’

II

Mr Clarke’s Memoirs

Mr Clarke, the gentleman chosen by Dr Raymond to witness the strange experiment of the god Pan, was a person in whose character caution and curiosity were oddly mingled. In his sober moments he thought of the unusual and the eccentric with undisguised aversion, and yet, deep in his heart, there was a wide-eyed inquisitiveness with respect to all the more recondite and esoteric elements in the nature of men. The latter tendency had prevailed when he accepted Raymond’s invitation, for though his considered judgment had always repudiated the doctor’s theories as the wildest nonsense, yet he secretly hugged a belief in fantasy, and would have rejoiced to see that belief confirmed. The horrors that he witnessed in the dreary laboratory were to a certain extent salutary; he was conscious of being involved in an affair not altogether reputable, and for many years afterwards he clung bravely to the commonplace, and rejected all occasions of occult investigation. Indeed, on some homeopathic principle, he for some time attended the séances of distinguished mediums, hoping that the clumsy tricks of these gentlemen would make him altogether disgusted with occultism of every kind6, but the remedy, though caustic, was not efficacious. Clarke knew that he still pined for the unseen, and little by little the old passion began to reassert itself, as the face of Mary, shuddering and convulsed with an unknowable terror, faded slowly from his memory. Occupied all day in pursuits both serious and lucrative, the temptation to relax in the evening was too great, especially in the winter months, when the fire cast a warm glow over his snug bachelor apartment, and a bottle of some choice claret stood ready by his elbow. His dinner digested, he would make a brief pretence of reading the evening paper, but the mere catalogue of news soon palled upon him, and Clarke would find himself casting glances of warm desire in the direction of an old Japanese bureau, which stood at a pleasant distance from the hearth. Like a boy before a jam closet, for a few minutes he would hover indecisive, but lust always prevailed, and Clarke ended by drawing up his chair, lighting a candle, and sitting down before the bureau. Its pigeonholes and drawers teemed with documents on the most morbid subjects, and in the well reposed a large manuscript volume, in which he had painfully entered the gems of his collection. Clarke had a fine contempt for published literature; the most ghostly story ceased to interest him if it happened to be printed; his sole pleasure was in the reading, compiling, arranging and rearranging what he called his ‘Memoirs to prove the Existence of the Devil’7, and engaged in this pursuit the evening seemed to fly and the night appeared too short.

On one particular evening, an ugly December night, black with fog and raw with frost, Clarke hurried over his dinner, and scarcely deigned to observe his customary ritual of taking up the paper and putting it down again. He paced two or three times up and down the room, and opened the bureau, stood still a moment, and sat down. He leant back, absorbed in one of those dreams to which he was subject, and at length drew out his book, and opened it at the last entry. There were three or four pages densely covered with Clarke’s round, set penmanship, and at the beginning he had written in a somewhat larger hand:

Singular Narrative told me by my Friend, Dr Phillips. He assures me that all the Facts related therein are strictly and wholly True, but refuses to give either the Surnames of the Persons concerned, or the Place where these Extraordinary Events occurred.

Mr Clarke began to read over the account for the tenth time, glancing now and then at the pencil notes he had made when it was told him by his friend. It was one of his humours to pride himself on a certain literary ability; he thought well of his style, and took pains in arranging the circumstances in dramatic order. He read the following story:

The persons concerned in this statement are Helen V., who, if she is still alive, must now be a woman of twenty-three, Rachel M., since deceased, who was a year younger than the above, and Trevor W., an imbecile, aged eighteen. These persons were at the period of the story inhabitants of a village on the borders of Wales8, a place of some importance in the time of the Roman occupation, but now a scattered hamlet of not more than five hundred souls. It is situated on rising ground, about six miles from the sea, and is sheltered by a large and picturesque forest. Some eleven years ago, Helen V. came to the village under rather peculiar circumstances. It is understood that she, being an orphan, was adopted in her infancy by a distant relative, who brought her up in his own house till she was twelve years old. Thinking, however, that it would be better for the child to have playmates of her own age, he advertised in several local papers for a good home in a comfortable farmhouse for a girl of twelve, and this advertisement was answered by Mr R., a well-to-do farmer in the above-mentioned village. His references proving satisfactory, the gentleman sent his adopted daughter to Mr R., with a letter, in which he stipulated that the girl should have a room to herself, and stated that her guardians need be at no trouble in the matter of education, as she was already sufficiently educated for the position in life which she would occupy. In fact, Mr R. was given to understand that the girl was to be allowed to find her own occupations, and to spend her time almost as she