Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jazzybee Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

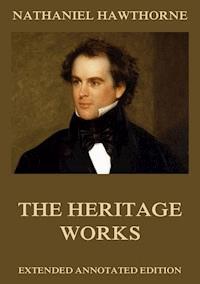

The Heritage Works are Hawthorne's works that were left unfinished or unattended after his death. Contents: Fanshawe Septimius Felton The Ancestral Footstep The Dolliver Romance

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 774

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Heritage Works

Nathaniel Hawthorne

Contents:

Nathaniel Hawthorne – A Biographical Primer

Fanshawe

Introductory Note.

Chapter I.

Chapter Ii.

Chapter Iii.

Chapter Iv.

Chapter V

Chapter Vi.

Chapter Vii.

Chapter Viii.

Chapter Ix.

Chapter X.

Septimius Felton

Introductory Note.

Septimius Felton

The Ancestral Footstep

Introductory Note.

I.

Ii.

Iii.

The Dolliver Romance

Introductory Note To The Dolliver Romance.

A Scene From The Dolliver Romance.

Another Scene From The Dolliver Romance

Another Fragment Of The Dolliver Romance.

The Heritage Works, N. Hawthorne

Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck

86450 Altenmünster, Loschberg 9

Germany

ISBN:9783849641016

www.jazzybee-verlag.de

www.facebook.com/jazzybeeverlag

Nathaniel Hawthorne – A Biographical Primer

By Edward Everett Hale

American novelist: b. Salem, Mass., 4 July 1804; d. Plymouth, N. H., 19 May 1864. The founder of the family in America was William Hathorne (as the name was then spelled), a typical Puritan and a public man of importance. John, his son, was a judge, one of those presiding over the witchcraft trials. Of Joseph in the next generation little is said, but Daniel, next in decent, followed the sea and commanded a privateer in the Revolution, while his son Nathaniel, father of the romancer, was also a sea Captain. This pure New England descent gave a personal character to Hawthorne's presentations of New England life; when he writes of the strictness of the early Puritans, of the forests haunted by Indians, of the magnificence of the provincial days, of men high in the opinion of their towns-people, of the reaching out to far lands and exotic splendors, he is expressing the stored-up experience of his race. His father died when Nathaniel was but four and the little family lived a secluded life with his mother. He was a handsome boy and quite devoted to reading, by an early accident which for a time prevented outdoor games. His first school was with Dr. Worcester, the lexicographer. In 1818 his mother moved to Raymond, Me., where her brother had bought land, and Hawthorne went to Bowdoin College. He entered college at the age of 17 in the same class with Longfellow. In the class above him was Franklin Pierce, afterward 12th President of the United States. On being graduated in 1825 Hawthorne determined upon literature as a profession, but his first efforts were without success. ‘Fanshawe’ was published anonymously in 1828, and shorter tales and sketches were without importance. Little need be said of these earlier years save to note that they were full of reading and observation. In 1836 he edited in Boston the AmericanMagazine for Useful and Entertaining Knowledge, but gained little from it save an introduction to ‘The Token,’ in which his tales first came to be known. Returning to Salem he lived a very secluded life, seeing almost no one (rather a family trait), and devoted to his thoughts and imaginations. He was a strong and powerful man, of excellent health and, though silent, cheerful, and a delightful companion when be chose. But intellectually he was of a separated and individual type, having his own extravagances and powers and submitting to no companionship in influence. In 1837 appeared ‘Twice Told Tales’ in book form: in a preface written afterward Hawthorne says that he was at this time “the obscurest man of letters in America.” Gradually he began to be more widely received. In 1839 he became engaged to Miss Sophia Peabody, but was not married for some years. In 1838 he was appointed to a place in the Boston custom house, but found that he could not easily save time enough for literature and was not very sorry when the change of administration put him out of office. In 1841 was founded the socialistic community at Brook Farm: it seemed to Hawthorne that here was a chance for a union of intellectual and physical work, whereby he might make a suitable home for his future wife. It failed to fulfil his expectations and Hawthorne withdrew from the experiment. In 1842 he was married and moved with his wife to the Old Manse at Concord just above the historic bridge. Here chiefly he wrote the ‘Mosses of an Old Manse’ (1846). In 1845 he published a second series of ‘Twice Told Tales’; in this year also the family moved to Salem, where he had received the appointment of surveyor at the custom house. As before, official work was a hindrance to literature; not till 1849 when he lost his position could he work seriously. He used his new-found leisure in carrying out a theme that had been long in his mind and produced ‘The Scarlet Letter’ in 1850. This, the first of his longer novels, was received with enthusiasm and at once gave him a distinct place in literature. He now moved to Lenox, Mass., where he began on ‘The House of Seven Gables,’ which was published in 1851. He also wrote ‘A Wonder-Book’ here, which in its way has become as famous as his more important work. In December 1851 he moved to West Newton, and shortly to Concord again, this time to the Wayside. At Newton he wrote ‘The Blithedale Romance.’ Having settled himself at Concord in the summer of 1852, his first literary work was to write the life of his college friend, Franklin Pierce, just nominated for the Presidency. This done he turned to ‘Tanglewood Tales,’ a volume not unlike the ‘Wonder-Book.’ In 1853 he was named consul to Liverpool: at first he declined the position, but finally resolved to take this opportunity to see something of Europe. He spent four years in England, and then a year in Italy. As before, he could write nothing while an official, and resigned in 1857 to go to Rome, where he passed the winter, and to Florence, where he received suggestions and ideas which gave him stimulus for literary work. The summer of 1858 he passed at Redcar, in Yorkshire, where he wrote ‘The Marble Faun.’ In June 1860 he sailed for America, where he returned to the Wayside. For a time he did little literary work; in 1863 he published ‘Our Old Home,’ a series of sketches of English life, and planned a new novel, ‘The Dolliver Romance,’ also called ‘Pansie.’ But though he suffered from no disease his vitality seemed relaxed; some unfortunate accidents had a depressing effect, and in the midst of a carriage trip into the White Mountains with his old friend, Franklin Pierce, he died suddenly at Plymouth, N. H., early in the morning, 19 May 1864.

The works of Hawthorne consist of novels, short stories, tales for children, sketches of life and travel and some miscellaneous pieces of a biographical or descriptive character. Besides these there were published after his death extracts from his notebooks. Of his novels ‘The Scarlet Letter’ is a story of old New England; it has a powerful moral idea at bottom, but it is equally strong in its presentation of life and character in the early days of Massachusetts. ‘House of the Seven Gables’ presents New England life of a later date; there is more of careful analysis and presentation of character and more description of life and manners, but less moral intensity. ‘The Blithedale Romance’ is less strong; Hawthorne seems hardly to grasp his subject. It makes the third in what may be called a series of romances presenting the molding currents of New England life: the first showing the factors of religion and sin, the second the forces of hereditary good and evil, and the third giving a picture of intellectual and emotional ferment in a society which had come from very different beginnings. ‘Septimius Felton,’ finished in the main but not published by Hawthorne, is a fantastic story dealing with the idea of immortality. It was put aside by Hawthorne when he began to write ‘The Dolliver Romance,’ of which he completed only the first chapters. ‘Dr. Grimshaw's Secret’ (published in 1882) is also not entirely finished. These three books represent a purpose that Hawthorne never carried out. He had presented New England life, with which the life of himself and his ancestry was so indissolubly connected, in three characteristic phases. He had traced New England history to its source. He now looked back across the ocean to the England he had learned to know, and thought of a tale that should bridge the gulf between the Old World and the New. But the stories are all incomplete and should be read only by the student. The same thing may be said of ‘Fanshawe,’ which was published anonymously early in Hawthorne's life and later withdrawn from circulation. ‘The Marble Faun’ presents to us a conception of the Old World at its oldest point. It is Hawthorne's most elaborate work, and if every one were familiar with the scenes so discursively described, would probably be more generally considered his best. Like the other novels its motive is based on the problem of evil, but we have not precisely atonement nor retribution, as in his first two novels. The story is one of development, a transformation of the soul through the overcoming of evil. The four novels constitute the foundation of Hawthorne's literary fame and character, but the collections of short stories do much to develop and complete the structure. They are of various kinds, as follows: (1) Sketches of current life or of history, as ‘Rills from the Town Pump,’ ‘The Village Uncle,’ ‘Main Street,’ ‘Old News.’ These are chiefly descriptive and have little story; there are about 20 of them. (2) Stories of old New England, as ‘The Gray Champion,’ ‘The Gentle Boy,’ ‘Tales of the Province House.’ These stories are often illustrative of some idea and so might find place in the next set. (3) Stories based upon some idea, as ‘Ethan Brand,’ which presents the idea of the unpardonable sin; ‘The Minister's Black Veil,’ the idea of the separation of each soul from its fellows; ‘Young Goodman Brown,’ the power of doubt in good and evil. These are the most characteristic of Hawthorne's short stories; there are about a dozen of them. (4) Somewhat different are the allegories, as ‘The Great Stone Face,’ ‘Rappacini's Daughter,’ ‘The Great Carbuncle.’ Here the figures are not examples or types, but symbols, although in no story is the allegory consistent. (5) There are also purely fantastic developments of some idea, as ‘The New Adam and Eve,’ ‘The Christmas Banquet,’ ‘The Celestial Railroad.’ These differ from the others in that there is an almost logical development of some fancy, as in case of the first the idea of a perfectly natural pair being suddenly introduced to all the conventionalities of our civilization. There are perhaps 20 of these fantasies. Hawthorne's stories from classical mythology, the ‘Wonder-Book’ and ‘Tanglewood Tales,’ belong to a special class of books, those in which men of genius have retold stories of the past in forms suited to the present. The stories themselves are set in a piece of narrative and description which gives the atmosphere of the time of the writer, and the old legends are turned from stately myths not merely to children's stories, but to romantic fancies. Mr. Pringle in ‘Tanglewood Fireside’ comments on the idea: “Eustace,” he says to the young college student who had been telling the stories to the children, “pray let me advise you never more to meddle with a classical myth. Your imagination is altogether Gothic and will inevitably Gothicize everything that you touch. The effect is like bedaubing a marble statue with paint. This giant, now! How can you have ventured to thrust his huge disproportioned mass among the seemly outlines of Grecian fable?” “I described the giant as he appeared to me,” replied the student, “And, sir, if you would only bring your mind into such a relation to these fables as is necessary in order to remodel them, you would see at once that an old Greek has no more exclusive right to them than a modern Yankee has. They are the common property of the world and of all time” (“Wonder-Book,” p. 135). ‘Grandfather's Chair’ was also written primarily for children and gives narratives of New England history, joined together by a running comment and narrative from Grandfather, whose old chair had come to New England, not in the Mayflower, but with John Winthrop and the first settlers of Boston. ‘Biographical Stories,’ in a somewhat similar framework, tells of the lives of Franklin, Benjamin West and others. It should be noted of these books that Hawthorne's writings for children were always written with as much care and thought as his more serious work. ‘Our Old Home’ was the outcome of that less remembered side of Hawthorne's genius which was a master of the details of circumstance and surroundings. The notebooks give us this also, but the American notebook has also rather a peculiar interest in giving us many of Hawthorne's first ideas which were afterward worked out into stories and sketches.

One element in Hawthorne's intellectual make-up was his interest in the observation of life and his power of description of scenes, manners and character. This is to be seen especially, as has been said, in his notebooks and in ‘Our Old Home,’ and in slightly modified form in the sketches noted above. These studies make up a considerable part of ‘Twice Told Tales’ and ‘Mosses from an Old Manse,’ and represent a side of Hawthorne's genius not always borne in mind. Had this interest been predominant in him we might have had in Hawthorne as great a novelist of our everyday life as James or Howells. In the ‘House of Seven Gables’ the power comes into full play; 100 pages hardly complete the descriptions of the simple occupations of a single uneventful day. In Hawthorne, however, this interest in the life around him was mingled with a great interest in history, as we may see, not only in the stories of old New England noted above, but in the descriptive passages of ‘The Scarlet Letter.’ Still we have not, even here, the special quality for which we know Hawthorne. Many great realists have written historical novels, for the same curiosity that absorbs one in the affairs of everyday may readily absorb one in the recreation of the past. In Hawthorne, however, was another element very different. His imagination often furnished him with conceptions having little connection with the actual circumstances of life. The fanciful developments of an idea noted above (5) have almost no relation to fact: they are “made up out of his own head.” They are fantastic enough, but generally they are developments of some moral idea and a still more ideal development of such conceptions was not uncommon in Hawthorne. ‘Rappacini's Daughter’ is an allegory in which the idea is given a wholly imaginary setting, not resembling anything that Hawthorne had ever known from observation. These two elements sometimes appear in Hawthorne's work separate and distinct just as they did in his life: sometimes he secluded himself in his room, going out only after nightfall; sometimes he wandered through the country observing life and meeting with everybody. But neither of these elements alone produced anything great, probably because for anything great we need the whole man. The true Hawthorne was a combination of these two elements, with various others of personal character, and artistic ability that cannot be specified here. The most obvious combination between these two elements, so far as literature is concerned, between the fact of external life and the idea of inward imagination, is by a symbol. The symbolist sees in everyday facts a presentation of ideas. Hawthorne wrote a number of tales that are practically allegories: ‘The Great Stone Face’ uses facts with which Hawthorne was familiar, persons and scenes that he knew, for the presentation of a conception of the ideal. His novels, too, are full of symbolism. ‘The Scarlet Letter’ itself is a symbol and the rich clothing of Little Pearl, Alice's posies among the Seven Gables, the old musty house itself, are symbols, Zenobia's flower, Hilda's doves. But this is not the highest synthesis of power, as Hawthorne sometimes felt himself, as when he said of ‘The Great Stone Face,’ that the moral was too plain and manifest for a work of art. However much we may delight in symbolism it must be admitted that a symbol that represents an idea only by a fanciful connection will not bear the seriousness of analysis of which a moral idea must be capable. A scarlet letter A has no real connection with adultery, which begins with A and is a scarlet sin only to such as know certain languages and certain metaphors. So Hawthorne aimed at a higher combination of the powers of which he was quite aware, and found it in figures and situations in which great ideas are implicit. In his finest work we have, not the circumstance before the conception or the conception before the circumstance, as in allegory. We have the idea in the fact, as it is in life, the two inseparable. Hester Prynne's life does not merely present to us the idea that the breaking of a social law makes one a stranger to society with its advantages and disadvantages. Hester is the result of her breaking that law. The story of Donatello is not merely a way of conveying the idea that the soul which conquers evil thereby grows strong in being and life. Donatello himself is such a soul growing and developing. We cannot get the idea without the fact, nor the fact without the idea. This is the especial power of Hawthorne, the power of presenting truth implicit in life. Add to this his profound preoccupation with the problem of evil in this world, with its appearance, its disappearance, its metamorphoses, and we have a due to Hawthorne's greatest works. In ‘The Scarlet Letter,’ ‘The House of Seven Gables,’ ‘The Marble Faun,’ ‘Ethan Brand,’ ‘The Gray Champion,’ the ideas cannot be separated from the personalities which express them. It is this which constitutes Hawthorne's lasting power in literature. His observation is interesting to those that care for the things that he describes, his fancy amuses, or charms or often stimulates our ideas. His short stories are interesting to a student of literature because they did much to give a definite character to a literary form which has since become of great importance. His novels are exquisite specimens of what he himself called the romance, in which the figures and scenes are laid in a world a little more poetic than that which makes up our daily surrounding. But Hawthorne's really great power lay in his ability to depict life so that we are made keenly aware of the dominating influence of moral motive and moral law.

Fanshawe

Introductory Note.

In 1828, three years after graduating from Bowdoin College, Hawthorne published his first romance, "Fanshawe." It was issued at Boston by Marsh & Capen, but made little or no impression on the public. The motto on the title-page of the original was from Southey: "Wilt thou go on with me?"

Afterwards, when he had struck into the vein of fiction that came to be known as distinctively his own, he attempted to suppress this youthful work, and was so successful that he obtained and destroyed all but a few of the copies then extant.

Some twelve years after his death it was resolved, in view of the interest manifested in tracing the growth of his genius from the beginning of his activity as an author, to revive this youthful romance; and the reissue of "Fanshawe" was then made.

Little biographical interest attaches to it, beyond the fact that Mr. Longfellow found in the descriptions and general atmosphere of the book a decided suggestion of the situation of Bowdoin College, at Brunswick, Maine, and the life there at the time when he and Hawthorne were both undergraduates of that institution.

Professor Packard, of Bowdoin College, who was then in charge of the study of English literature, and has survived both of his illustrious pupils, recalls Hawthorne's exceptional excellence in the composition of English, even at that date (1821-1825); and it is not impossible that Hawthorne intended, through the character of Fanshawe, to present some faint projection of what he then thought might be his own obscure history. Even while he was in college, however, and meditating perhaps the slender elements of this first romance, his fellow-student Horatio Bridge, whose "Journal of an African Cruiser" he afterwards edited, recognized in him the possibilities of a writer of fiction—a fact to which Hawthorne alludes in the dedicatory Preface to "The Snow-Image."

G. P. L.

Chapter I.

"Our court shall be a little Academe."—SHAKESPEARE.

In an ancient though not very populous settlement, in a retired corner of one of the New England States, arise the walls of a seminary of learning, which, for the convenience of a name, shall be entitled "Harley College." This institution, though the number of its years is inconsiderable compared with the hoar antiquity of its European sisters, is not without some claims to reverence on the score of age; for an almost countless multitude of rivals, by many of which its reputation has been eclipsed, have sprung up since its foundation. At no time, indeed, during an existence of nearly a century, has it acquired a very extensive fame; and circumstances, which need not be particularized, have, of late years, involved it in a deeper obscurity. There are now few candidates for the degrees that the college is authorized to bestow. On two of its annual "Commencement Days," there has been a total deficiency of baccalaureates; and the lawyers and divines, on whom doctorates in their respective professions are gratuitously inflicted, are not accustomed to consider the distinction as an honor. Yet the sons of this seminary have always maintained their full share of reputation, in whatever paths of life they trod. Few of them, perhaps, have been deep and finished scholars; but the college has supplied—what the emergencies of the country demanded—a set of men more useful in its present state, and whose deficiency in theoretical knowledge has not been found to imply a want of practical ability.

The local situation of the college, so far secluded from the sight and sound of the busy world, is peculiarly favorable to the moral, if not to the literary, habits of its students; and this advantage probably caused the founders to overlook the inconveniences that were inseparably connected with it. The humble edifices rear themselves almost at the farthest extremity of a narrow vale, which, winding through a long extent of hill-country, is wellnigh as inaccessible, except at one point, as the Happy Valley of Abyssinia. A stream, that farther on becomes a considerable river, takes its rise at, a short distance above the college, and affords, along its wood-fringed banks, many shady retreats, where even study is pleasant, and idleness delicious. The neighborhood of the institution is not quite a solitude, though the few habitations scarcely constitute a village. These consist principally of farm-houses, of rather an ancient date (for the settlement is much older than the college), and of a little inn, which even in that secluded spot does not fail of a moderate support. Other dwellings are scattered up and down the valley; but the difficulties of the soil will long avert the evils of a too dense population. The character of the inhabitants does not seem—as there was, perhaps, room to anticipate—to be in any degree influenced by the atmosphere of Harley College. They are a set of rough and hardy yeomen, much inferior, as respects refinement, to the corresponding classes in most other parts of our country. This is the more remarkable, as there is scarcely a family in the vicinity that has not provided, for at least one of its sons, the advantages of a "liberal education."

Having thus described the present state of Harley College, we must proceed to speak of it as it existed about eighty years since, when its foundation was recent, and its prospects flattering. At the head of the institution, at this period, was a learned and Orthodox divine, whose fame was in all the churches. He was the author of several works which evinced much erudition and depth of research; and the public, perhaps, thought the more highly of his abilities from a singularity in the purposes to which he applied them, that added much to the curiosity of his labors, though little to their usefulness. But, however fanciful might be his private pursuits, Dr. Melmoth, it was universally allowed, was diligent and successful in the arts of instruction. The young men of his charge prospered beneath his eye, and regarded him with an affection that was strengthened by the little foibles which occasionally excited their ridicule. The president was assisted in the discharge of his duties by two inferior officers, chosen from the alumni of the college, who, while they imparted to others the knowledge they had already imbibed, pursued the study of divinity under the direction of their principal. Under such auspices the institution grew and flourished. Having at that time but two rivals in the country (neither of them within a considerable distance), it became the general resort of the youth of the Province in which it was situated. For several years in succession, its students amounted to nearly fifty,—a number which, relatively to the circumstances of the country, was very considerable.

From the exterior of the collegians, an accurate observer might pretty safely judge how long they had been inmates of those classic walls. The brown cheeks and the rustic dress of some would inform him that they had but recently left the plough to labor in a not less toilsome field; the grave look, and the intermingling of garments of a more classic cut, would distinguish those who had begun to acquire the polish of their new residence; and the air of superiority, the paler cheek, the less robust form, the spectacles of green, and the dress, in general of threadbare black, would designate the highest class, who were understood to have acquired nearly all the science their Alma Mater could bestow, and to be on the point of assuming their stations in the world. There were, it is true, exceptions to this general description. A few young men had found their way hither from the distant seaports; and these were the models of fashion to their rustic companions, over whom they asserted a superiority in exterior accomplishments, which the fresh though unpolished intellect of the sons of the forest denied them in their literary competitions. A third class, differing widely from both the former, consisted of a few young descendants of the aborigines, to whom an impracticable philanthropy was endeavoring to impart the benefits of civilization.

If this institution did not offer all the advantages of elder and prouder seminaries, its deficiencies were compensated to its students by the inculcation of regular habits, and of a deep and awful sense of religion, which seldom deserted them in their course through life. The mild and gentle rule of Dr. Melmoth, like that of a father over his children, was more destructive to vice than a sterner sway; and though youth is never without its follies, they have seldom been more harmless than they were here. The students, indeed, ignorant of their own bliss, sometimes wished to hasten the time of their entrance on the business of life; but they found, in after-years, that many of their happiest remembrances, many of the scenes which they would with least reluctance live over again, referred to the seat of their early studies. The exceptions to this remark were chiefly those whose vices had drawn down, even from that paternal government, a weighty retribution.

Dr. Melmoth, at the time when he is to be introduced to the reader, had borne the matrimonial yoke (and in his case it was no light burden) nearly twenty years. The blessing of children, however, had been denied him,—a circumstance which he was accustomed to consider as one of the sorest trials that checkered his pathway; for he was a man of a kind and affectionate heart, that was continually seeking objects to rest itself upon. He was inclined to believe, also, that a common offspring would have exerted a meliorating influence on the temper of Mrs. Melmoth, the character of whose domestic government often compelled him to call to mind such portions of the wisdom of antiquity as relate to the proper endurance of the shrewishness of woman. But domestic comforts, as well as comforts of every other kind, have their drawbacks; and, so long as the balance is on the side of happiness, a wise man will not murmur. Such was the opinion of Dr. Melmoth; and with a little aid from philosophy, and more from religion, he journeyed on contentedly through life. When the storm was loud by the parlor hearth, he had always a sure and quiet retreat in his study; and there, in his deep though not always useful labors, he soon forgot whatever of disagreeable nature pertained to his situation. This small and dark apartment was the only portion of the house to which, since one firmly repelled invasion, Mrs. Melmoth's omnipotence did not extend. Here (to reverse the words of Queen Elizabeth) there was "but one master and no mistress"; and that man has little right to complain who possesses so much as one corner in the world where he may be happy or miserable, as best suits him. In his study, then, the doctor was accustomed to spend most of the hours that were unoccupied by the duties of his station. The flight of time was here as swift as the wind, and noiseless as the snow- flake; and it was a sure proof of real happiness that night often came upon the student before he knew it was midday.

Dr. Melmoth was wearing towards age (having lived nearly sixty years), when he was called upon to assume a character to which he had as yet been a stranger. He had possessed in his youth a very dear friend, with whom his education had associated him, and who in his early manhood had been his chief intimate. Circumstances, however, had separated them for nearly thirty years, half of which had been spent by his friend, who was engaged in mercantile pursuits, in a foreign country. The doctor had, nevertheless, retained a warm interest in the welfare of his old associate, though the different nature of their thoughts and occupations had prevented them from corresponding. After a silence of so long continuance, therefore, he was surprised by the receipt of a letter from his friend, containing a request of a most unexpected nature.

Mr. Langton had married rather late in life; and his wedded bliss had been but of short continuance. Certain misfortunes in trade, when he was a Benedict of three years' standing, had deprived him of a large portion of his property, and compelled him, in order to save the remainder, to leave his own country for what he hoped would be but a brief residence in another. But, though he was successful in the immediate objects of his voyage, circumstances occurred to lengthen his stay far beyond the period which he had assigned to it. It was difficult so to arrange his extensive concerns that they could be safely trusted to the management of others; and, when this was effected, there was another not less powerful obstacle to his return. His affairs, under his own inspection, were so prosperous, and his gains so considerable, that, in the words of the old ballad, "He set his heart to gather gold"; and to this absorbing passion he sacrificed his domestic happiness. The death of his wife, about four years after his departure, undoubtedly contributed to give him a sort of dread of returning, which it required a strong effort to overcome. The welfare of his only child he knew would be little affected by this event; for she was under the protection of his sister, of whose tenderness he was well assured. But, after a few more years, this sister, also, was taken away by death; and then the father felt that duty imperatively called upon him to return. He realized, on a sudden, how much of life he had thrown away in the acquisition of what is only valuable as it contributes to the happiness of life, and how short a tune was left him for life's true enjoyments. Still, however, his mercantile habits were too deeply seated to allow him to hazard his present prosperity by any hasty measures; nor was Mr. Langton, though capable of strong affections, naturally liable to manifest them violently. It was probable, therefore, that many months might yet elapse before he would again tread the shores of his native country.

But the distant relative, in whose family, since the death of her aunt, Ellen Langton had remained, had been long at variance with her father, and had unwillingly assumed the office of her protector. Mr. Langton's request, therefore, to Dr. Melmoth, was, that his ancient friend (one of the few friends that time had left him) would be as a father to his daughter till he could himself relieve him of the charge.

The doctor, after perusing the epistle of his friend, lost no time in laying it before Mrs. Melmoth, though this was, in truth, one of the very few occasions on which he had determined that his will should be absolute law. The lady was quick to perceive the firmness of his purpose, and would not (even had she been particularly averse to the proposed measure) hazard her usual authority by a fruitless opposition. But, by long disuse, she had lost the power of consenting graciously to any wish of her husband's.

"I see your heart is set upon this matter," she observed; "and, in truth, I fear we cannot decently refuse Mr. Langton's request. I see little good of such a friend, doctor, who never lets one know he is alive till he has a favor to ask."

"Nay; but I have received much good at his hand," replied Dr. Melmoth; "and, if he asked more of me, it should be done with a willing heart. I remember in my youth, when my worldly goods were few and ill managed (I was a bachelor, then, dearest Sarah, with none to look after my household), how many times I have been beholden to him. And see—in his letter he speaks of presents, of the produce of the country, which he has sent both to you and me."

"If the girl were country-bred," continued the lady, "we might give her house-room, and no harm done. Nay, she might even be a help to me; for Esther, our maid-servant, leaves us at the mouth's end. But I warrant she knows as little of household matters as you do yourself, doctor."

"My friend's sister was well grounded in the re familiari" answered her husband; "and doubtless she hath imparted somewhat of her skill to this damsel. Besides, the child is of tender years, and will profit much by your instruction and mine."

"The child is eighteen years of age, doctor," observed Mrs. Melmoth, "and she has cause to be thankful that she will have better instruction than yours."

This was a proposition that Dr. Melmoth did not choose to dispute; though he perhaps thought that his long and successful experience in the education of the other sex might make him an able coadjutor to his wife in the care of Ellen Langton. He determined to journey in person to the seaport where his young charge resided, leaving the concerns of Harley College to the direction of the two tutors. Mrs. Melmoth, who, indeed, anticipated with pleasure the arrival of a new subject to her authority, threw no difficulties in the way of his intention. To do her justice, her preparations for his journey, and the minute instructions with which she favored him, were such as only a woman's true affection could have suggested. The traveller met with no incidents important to this tale; and, after an absence of about a fortnight, he and Ellen alighted from their steeds (for on horseback had the journey been performed) in safety at his own door.

If pen could give an adequate idea of Ellen Langton's loveliness, it would achieve what pencil (the pencils, at least, of the colonial artists who attempted it) never could; for, though the dark eyes might be painted, the pure and pleasant thoughts that peeped through them could only be seen and felt. But descriptions of beauty are never satisfactory. It must, therefore, be left to the imagination of the reader to conceive of something not more than mortal, nor, indeed, quite the perfection of mortality, but charming men the more, because they felt, that, lovely as she was, she was of like nature to themselves.

From the time that Ellen entered Dr. Melmoth's habitation, the sunny days seemed brighter and the cloudy ones less gloomy, than he had ever before known them. He naturally delighted in children; and Ellen, though her years approached to womanhood, had yet much of the gayety and simple happiness, because the innocence, of a child. She consequently became the very blessing of his life,—the rich recreation that he promised himself for hours of literary toil. On one occasion, indeed, he even made her his companion in the sacred retreat of his study, with the purpose of entering upon a course of instruction in the learned languages. This measure, however, he found inexpedient to repeat; for Ellen, having discovered an old romance among his heavy folios, contrived, by the charm of her sweet voice, to engage his attention therein till all more important concerns were forgotten.

With Mrs. Melmoth, Ellen was not, of course, so great a favorite as with her husband; for women cannot so readily as men, bestow upon the offspring of others those affections that nature intended for their own; and the doctor's extraordinary partiality was anything rather than a pledge of his wife's. But Ellen differed so far from the idea she had previously formed of her, as a daughter of one of the principal merchants, who were then, as now, like nobles in the land, that the stock of dislike which Mrs. Melmoth had provided was found to be totally inapplicable. The young stranger strove so hard, too (and undoubtedly it was a pleasant labor), to win her love, that she was successful to a degree of which the lady herself was not, perhaps, aware. It was soon seen that her education had not been neglected in those points which Mrs. Melmoth deemed most important. The nicer departments of cookery, after sufficient proof of her skill, were committed to her care; and the doctor's table was now covered with delicacies, simple indeed, but as tempting on account of their intrinsic excellence as of the small white hands that made them. By such arts as these,—which in her were no arts, but the dictates of an affectionate disposition,—by making herself useful where it was possible, and agreeable on all occasions, Ellen gained the love of everyone within the sphere of her influence.

But the maiden's conquests were not confined to the members of Dr. Melmoth's family. She had numerous admirers among those whose situation compelled them to stand afar off, and gaze upon her loveliness, as if she were a star, whose brightness they saw, but whose warmth they could not feel. These were the young men of Harley College, whose chief opportunities of beholding Ellen were upon the Sabbaths, when she worshipped with them in the little chapel, which served the purposes of a church to all the families of the vicinity. There was, about this period (and the fact was undoubtedly attributable to Ellen's influence,) a general and very evident decline in the scholarship of the college, especially in regard to the severer studies. The intellectual powers of the young men seemed to be directed chiefly to the construction of Latin and Greek verse, many copies of which, with a characteristic and classic gallantry, were strewn in the path where Ellen Langton was accustomed to walk. They, however, produced no perceptible effect; nor were the aspirations of another ambitious youth, who celebrated her perfections in Hebrew, attended with their merited success.

But there was one young man, to whom circumstances, independent of his personal advantages, afforded a superior opportunity of gaining Ellen's favor. He was nearly related to Dr. Melmoth, on which account he received his education at Harley College, rather than at one of the English universities, to the expenses of which his fortune would have been adequate. This connection entitled him to a frequent and familiar access to the domestic hearth of the dignitary,—an advantage of which, since Ellen Langton became a member of the family, he very constantly availed himself.

Edward Walcott was certainly much superior, in most of the particulars of which a lady takes cognizance, to those of his fellow-students who had come under Ellen's notice. He was tall; and the natural grace of his manners had been improved (an advantage which few of his associates could boast) by early intercourse with polished society. His features, also, were handsome, and promised to be manly and dignified when they should cease to be youthful. His character as a scholar was more than respectable, though many youthful follies, sometimes, perhaps, approaching near to vices, were laid to his charge. But his occasional derelictions from discipline were not such as to create any very serious apprehensions respecting his future welfare; nor were they greater than, perhaps, might be expected from a young man who possessed a considerable command of money, and who was, besides, the fine gentleman of the little community of which he was a member,—a character which generally leads its possessor into follies that he would otherwise have avoided.

With this youth Ellen Langton became familiar, and even intimate; for he was her only companion, of an age suited to her own, and the difference of sex did not occur to her as an objection. He was her constant companion on all necessary and allowable occasions, and drew upon himself, in consequence, the envy of the college.

Chapter Ii.

"Why, all delights are vain, but that most vain, Which, with pain purchased, doth inherit pain: As painfully to pore upon a book To seek the light of truth, while truth, the while, Doth falsely blind the eyesight of his look." SHAKESPEARE.

On one of the afternoons which afforded to the students a relaxation from their usual labors, Ellen was attended by her cavalier in a little excursion over the rough bridle-roads that led from her new residence. She was an experienced equestrian,—a necessary accomplishment at that period, when vehicles of every kind were rare. It was now the latter end of spring; but the season had hitherto been backward, with only a few warm and pleasant days. The present afternoon, however, was a delicious mingling of spring and summer, forming in their union an atmosphere so mild and pure, that to breathe was almost a positive happiness. There was a little alternation of cloud across the brow of heaven, but only so much as to render the sunshine more delightful.

The path of the young travellers lay sometimes among tall and thick standing trees, and sometimes over naked and desolate hills, whence man had taken the natural vegetation, and then left the soil to its barrenness. Indeed, there is little inducement to a cultivator to labor among the huge stones which there peep forth from the earth, seeming to form a continued ledge for several miles. A singular contrast to this unfavored tract of country is seen in the narrow but luxuriant, though sometimes swampy, strip of interval, on both sides of the stream, that, as has been noticed, flows down the valley. The light and buoyant spirits of Edward Walcott and Ellen rose higher as they rode on; and their way was enlivened, wherever its roughness did not forbid, by their conversation and pleasant laughter. But at length Ellen drew her bridle, as they emerged from a thick portion of the forest, just at the foot of a steep hill.

"We must have ridden far," she observed,—"farther than I thought. It will be near sunset before we can reach home."

"There are still several hours of daylight," replied Edward Walcott; "and we will not turn back without ascending this hill. The prospect from the summit is beautiful, and will be particularly so now, in this rich sunlight. Come, Ellen,—one light touch of the whip,—your pony is as fresh as when we started."

On reaching the summit of the hill, and looking back in the direction in which they had come, they could see the little stream, peeping forth many times to the daylight, and then shrinking back into the shade. Farther on, it became broad and deep, though rendered incapable of navigation, in this part of its course, by the occasional interruption of rapids.

"There are hidden wonders of rock and precipice and cave, in that dark forest," said Edward, pointing to the space between them and the river. "If it were earlier in the day, I should love to lead you there. Shall we try the adventure now, Ellen?"

"Oh no!" she replied. "Let us delay no longer. I fear I must even now abide a rebuke from Mrs. Melmoth, which I have surely deserved. But who is this, who rides on so slowly before us?"

She pointed to a horseman, whom they had not before observed. He was descending the hill; but, as his steed seemed to have chosen his own pace, he made a very inconsiderable progress.

"Oh, do you not know him? But it is scarcely possible you should," exclaimed her companion. "We must do him the good office, Ellen, of stopping his progress, or he will find himself at the village, a dozen miles farther on, before he resumes his consciousness."

"Has he then lost his senses?" inquired Miss Langton.

"Not so, Ellen,—if much learning has not made him mad," replied Edward Walcott. "He is a deep scholar and a noble fellow; but I fear we shall follow him to his grave erelong. Dr. Melmoth has sent him to ride in pursuit of his health. He will never overtake it, however, at this pace."

As he spoke, they had approached close to the subject of their conversation; and Ellen had a moment's space for observation before he started from the abstraction in which he was plunged. The result of her scrutiny was favorable, yet very painful.

The stranger could scarcely have attained his twentieth year, and was possessed of a face and form such as Nature bestows on none but her favorites. There was a nobleness on his high forehead, which time would have deepened into majesty; and all his features were formed with a strength and boldness, of which the paleness, produced by study and confinement, could not deprive them. The expression of his countenance was not a melancholy one: on the contrary, it was proud and high, perhaps triumphant, like one who was a ruler in a world of his own, and independent of the beings that surrounded him. But a blight, of which his thin pale cheek, and the brightness of his eye, were alike proofs, seemed to have come over him ere his maturity.

The scholar's attention was now aroused by the hoof-tramps at his side; and, starting, he fixed his eyes on Ellen, whose young and lovely countenance was full of the interest he had excited. A deep blush immediately suffused his cheek, proving how well the glow of health would have become it. There was nothing awkward, however, in his manner; and, soon recovering his self-possession, he bowed to her, and would have rode on.

"Your ride is unusually long to-day, Fanshawe," observed Edward Walcott. "When may we look for your return?"

The young man again blushed, but answered, with a smile that had a beautiful effect upon his countenance, "I was not, at the moment, aware in which direction my horse's head was turned. I have to thank you for arresting me in a journey which was likely to prove much longer than I intended."

The party had now turned their horses, and were about to resume their ride in a homeward direction; but Edward perceived that Fanshawe, having lost the excitement of intense thought, now looked weary and dispirited.

"Here is a cottage close at hand," he observed. "We have ridden far, and stand in need of refreshment. Ellen, shall we alight?"

She saw the benevolent motive of his proposal, and did not hesitate to comply with it. But, as they paused at the cottage door, she could not but observe that its exterior promised few of the comforts which they required. Time and neglect seemed to have conspired for its ruin; and, but for a thin curl of smoke from its clay chimney, they could not have believed it to be inhabited. A considerable tract of land in the vicinity of the cottage had evidently been, at some former period, under cultivation, but was now overrun by bushes and dwarf pines, among which many huge gray rocks, ineradicable by human art, endeavored to conceal themselves. About half an acre of ground was occupied by the young blades of Indian-corn, at which a half-starved cow gazed wistfully over the mouldering log-fence. These were the only agricultural tokens. Edward Walcott, nevertheless, drew the latch of the cottage door, after knocking loudly but in vain.

The apartment which was thus opened to their view was quite as wretched as its exterior had given them reason to anticipate. Poverty was there, with all its necessary and unnecessary concomitants. The intruders would have retired had not the hope of affording relief detained them.

The occupants of the small and squalid apartment were two women, both of them elderly, and, from the resemblance of their features, appearing to be sisters. The expression of their countenances, however, was very different. One, evidently the younger, was seated on the farther side of the large hearth, opposite to the door at which the party stood. She had the sallow look of long and wasting illness; and there was an unsteadiness of expression about her eyes, that immediately struck the observer. Yet her face was mild and gentle, therein contrasting widely with that of her companion.

The other woman was bending over a small fire of decayed branches, the flame of which was very disproportionate to the smoke, scarcely producing heat sufficient for the preparation of a scanty portion of food. Her profile only was visible to the strangers, though, from a slight motion of her eye, they perceived that she was aware of their presence. Her features were pinched and spare, and wore a look of sullen discontent, for which the evident wretchedness of her situation afforded a sufficient reason. This female, notwithstanding her years, and the habitual fretfulness (that is more wearing than time), was apparently healthy and robust, with a dry, leathery complexion. A short space elapsed before she thought proper to turn her face towards her visitors; and she then regarded them with a lowering eye, without speaking, or rising from her chair.

"We entered," Edward Walcott began to say, "in the hope"—But he paused, on perceiving that the sick woman had risen from her seat, and with slow and tottering footsteps was drawing near to him. She took his hand in both her own; and, though he shuddered at the touch of age and disease, he did not attempt to withdraw it. She then perused all his features, with an expression, at first of eager and hopeful anxiety, which faded by degrees into disappointment. Then, turning from him, she gazed into Fanshawe's countenance with the like eagerness, but with the same result. Lastly, tottering back to her chair, she hid her face and wept bitterly. The strangers, though they knew not the cause of her grief, were deeply affected; and Ellen approached the mourner with words of comfort, which, more from their tone than their meaning, produced a transient effect.

"Do you bring news of him?" she inquired, raising her head. "Will he return to me? Shall I see him before I die?" Ellen knew not what to answer; and, ere she could attempt it, the other female prevented her.

"Sister Butler is wandering in her mind," she said, "and speaks of one she will never behold again. The sight of strangers disturbs her, and you see we have nothing here to offer you."

The manner of the woman was ungracious; but her words were true. They saw that their presence could do nothing towards the alleviation of the misery they witnessed; and they felt that mere curiosity would not authorize a longer intrusion. So soon, therefore, as they had relieved, according to their power, the poverty that seemed to be the least evil of this cottage, they emerged into the open air.

The breath of heaven felt sweet to them, and removed a part of the weight from their young hearts, which were saddened by the sight of so much wretchedness. Perceiving a pure and bright little fountain at a short distance from the cottage, they approached it, and, using the bark of a birch-tree as a cup, partook of its cool waters. They then pursued their homeward ride with such diligence, that, just as the sun was setting, they came in sight of the humble wooden edifice which was dignified with the name of Harley College. A golden ray rested upon the spire of the little chapel, the bell of which sent its tinkling murmur down the valley to summon the wanderers to evening prayers.

Fanshawe returned to his chamber that night, and lighted his lamp as he had been wont to do. The books were around him which had hitherto been to him like those fabled volumes of Magic, from which the reader could not turn away his eye till death were the consequence of his studies. But there were unaccustomed thoughts in his bosom now; and to these, leaning his head on one of the unopened volumes, he resigned himself.

He called up in review the years, that, even at his early age, he had spent in solitary study, in conversation with the dead, while he had scorned to mingle with the living world, or to be actuated by any of its motives. He asked himself to what purpose was all this destructive labor, and where was the happiness of superior knowledge. He had climbed but a few steps of a ladder that reached to infinity: he had thrown away his life in discovering, that, after a thousand such lives, he should still know comparatively nothing. He even looked forward with dread—though once the thought had been dear to him—to the eternity of improvement that lay before him. It seemed now a weary way, without a resting-place and without a termination; and at that moment he would have preferred the dreamless sleep of the brutes that perish to man's proudest attribute,—of immortality.

Fanshawe had hitherto deemed himself unconnected with the world, Unconcerned in its feelings, and uninfluenced by it in any of his pursuits. In this respect he probably deceived himself. If his inmost heart could have been laid open, there would have been discovered that dream of undying fame, which, dream as it is, is more powerful than a thousand realities. But, at any rate, he had seemed, to others and to himself, a solitary being, upon whom the hopes and fears of ordinary men were ineffectual.

But now he felt the first thrilling of one of the many ties, that, so long as we breathe the common air, (and who shall say how much longer?) unite us to our kind. The sound of a soft, sweet voice, the glance of a gentle eye, had wrought a change upon him; and in his ardent mind a few hours had done the work of many. Almost in spite of himself, the new sensation was inexpressibly delightful. The recollection of his ruined health, of his habits (so much at variance with those of the world),—all the difficulties that reason suggested, were inadequate to check the exulting tide of hope and joy.

Chapter Iii.

"And let the aspiring youth beware of love,— Of the smooth glance beware; for 'tis too late When on his heart the torrent softness pours; Then wisdom prostrate lies, and fading fame Dissolves in air away." THOMSON.

A few months passed over the heads of Ellen Langton and her admirers, unproductive of events, that, separately, were of sufficient importance to be related. The summer was now drawing to a close; and Dr. Melmoth had received information that his friend's arrangements were nearly completed, and that by the next home-bound ship he hoped to return to his native country. The arrival of that ship was daily expected.

During the time that had elapsed since his first meeting with Ellen, there had been a change, yet not a very remarkable one, in Fanshawe's habits. He was still the same solitary being, so far as regarded his own sex; and he still confined himself as sedulously to his chamber, except for one hour— the sunset hour—of every day. At that period, unless prevented by the inclemency of the weather, he was accustomed to tread a path that wound along the banks of the stream. He had discovered that this was the most frequent scene of Ellen's walks; and this it was that drew him thither.

Their intercourse was at first extremely slight,—a bow on the one side, a smile on the other, and a passing word from both; and then the student hurried back to his solitude. But, in course of time, opportunities occurred for more extended conversation; so that, at the period with which this chapter is concerned, Fanshawe was, almost as constantly as Edward Walcott himself, the companion of Ellen's walks.

His passion had strengthened more than proportionably to the time that had elapsed since it was conceived; but the first glow and excitement which attended it had now vanished. He had reasoned calmly with himself, and rendered evident to his own mind the almost utter hopelessness of success. He had also made his resolution strong, that he would not even endeavor to win Ellen's love, the result of which, for a thousand reasons, could not be happiness. Firm in this determination, and confident of his power to adhere to it; feeling, also, that time and absence could not cure his own passion, and having no desire for such a cure,—he saw no reason for breaking off the intercourse that was established between Ellen and himself. It was remarkable, that, notwithstanding the desperate nature of his love, that, or something connected with it, seemed to have a beneficial effect upon his health. There was now a slight tinge of color in his cheek, and a less consuming brightness in his eye. Could it be that hope, unknown to himself, was yet alive in his breast; that a sense of the possibility of earthly happiness was redeeming him from the grave?

Had the character of Ellen Langton's mind been different, there might, perhaps, have been danger to her from an intercourse of this nature with such a being as Fanshawe; for he was distinguished by many of those asperities around which a woman's affection will often cling. But she was formed to walk in the calm and quiet paths of life, and to pluck the flowers of happiness from the wayside where they grow. Singularity of character, therefore, was not calculated to win her love. She undoubtedly felt an interest in the solitary student, and perceiving, with no great exercise of vanity, that her society drew him from the destructive intensity of his studies, she perhaps felt it a duty to exert her influence. But it did not occur to her that her influence had been sufficiently strong to change the whole current of his thoughts and feelings.

Ellen and her two lovers (for both, though perhaps not equally, deserved that epithet) had met, as usual, at the close of a sweet summer day, and were standing by the side of the stream, just where it swept into a deep pool. The current, undermining the bank, had formed a recess, which, according to Edward Walcott, afforded at that moment a hiding-place to a trout of noble size.

"Now would I give the world," he exclaimed with great interest, "for a hook and line, a fish-spear, or any piscatorial instrument of death! Look, Ellen, you can see the waving of his tail from beneath the bank!"