5,12 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

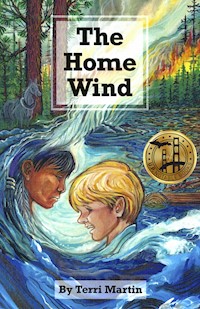

Jamie Kangas struggles with turbulent emotions caused by the death of his father, who perished in a logging accident--an accident for which Jamie blames himself. While his mother works as cook in a logging camp, Jamie is run ragged as chore boy. The grinding dreariness fades when Jamie meets a Native American boy, Gray Feather, who carries a burden of his own. The two boys become close friends as they face the challenges of a harsh environment and prejudiced world. And as trees fall to the lumberjack's blade, Jamie hears the ghostly words of his father, warning of future catastrophe.

The Home Wind is a middle-grade children's novel (ages 9 and up), which takes place during the 1870s in a Michigan logging camp. Quality paperback, 198 pages plus discussion guide.

"The Home Wind is an engaging story of two boys who must find their way through the difficulties of life on the road to becoming men. It is set during the 1870s in the Fox River logging camp near Seney in Upper Michigan. Jamie Kangas struggles with the guilt of feeling responsible for his father's death. He discovers a Native American boy, Gray Feather, hiding in the camp stables, nearly frozen and starved, who carries burdens of his own. Soon the two become close friends.

The author weaves the backstory of both boys through action and dialogue, with impeccably researched details. Her descriptions of the scenes and action make a reader feel as if they are right there in the middle of it all. Readers can't miss the symbolism found throughout the book and a wonderful way to learn about the past at the same time. This book should go far, and not just with young audiences. A great discussion guide can be found at the end of the book for classroom, homeschool, or adult book club use." -- Deborah K. Frontiera, U.P. Book Review

"The Home Wind is a beautiful novel for both middle grade readers and a wonderful a read for adults, too. Steeped in carefully researched historical events in Michigan's Upper Peninsula, The Home Wind is a delight. Martin's characters captured my heart and made the story come alive--two boys struggling to understand the world around them. This is also an important book for anyone interested in the history of Michigan's logging industry and in the Native peoples of Michigan. I highly recommend The Home Wind, and if you are looking for a gift for your middle reader, it's perfect!"

-- Sue Harrison, author of The Midwife's Touch

"The Home Wind" is a gripping story set in the U.P. circa 1870. The main character, Jamie, begins early to have guilt and maturity issues to overcome as a young boy growing up in a lumber camp in the Upper Peninsula. There are several points that really stand out. The main one is the Native American character and the friendship he develops with the main character. Both young boys have issues with their fathers and find ways to resolve that by the novel's end. Another highlight is the attention to historical detail. Martin really captures what a logging camp was like, what the town of Seney was like - famously wild, but perhaps only on weekends - and my favorite section was the Marinette/Menonimee fire which was dramatically and vividly depicted"

-- Tyler R. Tichelaar, author of The Marquette Trilogy

New Revised 2023 Edition from Modern History Press

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 234

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

© 2021 Gnarly Woods Publications

ISBN: 978-1-7352043-1-4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021906337

First Edition 2021

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by Gnarly Woods Publications

L’Anse, Michigan 49946

Cover art by Elizabeth Yelland

No portion of this publication may be reproduced, reprinted or otherwise copied for distribution purposes without the express written permission of the publisher.

THE HOME WIND

Gaa wiin daa aangoshkigaazo ahaw enaabiyaan gaa inaabid

You cannot destroy one who has dreamed a dream like mine. (Ojibwa saying)

CONTENTS

Part 1 Fox River Logging Camp

1 The Sluice Gate

2 An Eye for An Eye

3 Flaggin’s

4 Battles

5 Gray Feather

6 Stories

7 Babe and the Stray Dog

8 Seney

9 Bumgartner’s

10 Bartering

11 The Thief

12 Burdens

13 Ma

14 Question

Part 2 Menominee River Mill Town

15 Riding the Waves

16 Number 47

17 A Race to the River

18 The Bribe

19 Smoke

20 Fire!

21 The Home Wind

22 From the Ashes

PROLOGUE

April 27, 1870

“Close the sluice gate!” Jamie could barely hear his father’s shouts above the booming rush of the river. The water and logs exploded with a thunderous roar through the sluice gate that Jamie and a riverman named Pete struggled to slide closed. But it was stuck. Jamie, pushing with the full might of his twelve-year old body, was unable to budge his side of the gate.

“She’s gonna jam again,” Jamie’s father shouted from below as he fought his way along the bobbing and tumbling logs. The calks of his boots dug into bark, sending each log he stepped on into a spin before he leapt to another.

“Close the gate!” he shouted again.

But the water kept coming, its raging torrent carrying more giant logs through the sluiceway. Pete pushed Jamie aside and wrestled with the gate, but strong as Pete was, it was too much for one man. It was wedged tight at an angle because Jamie’s end had not gone down.

Jamie balanced on the dam, surrounded by the foaming boil of angry water and timber. Pete was cussing, his voice mixing with the pounding water. Jamie’s father was running across the unsteady bridge of logs, barely escaping disaster with each step.

“Lord in heaven, give me strength. Come back and help me, lad,” Pete shouted.

But Jamie stood paralyzed, as if his feet were nailed to the primitive dam structure. With unblinking eyes, he watched his father leaping from log to log. He could hear his father’s cries for help, even though he was much too far away and the river’s fury much too loud for any man’s voice to carry.

Jamie’s father was twenty feet from shore when he stumbled.

“Help me boy!” Pete screamed. “Lord, he’s going down. Hell and damnation! It’s too late.”

His father balanced briefly on his hands and knees then pitched headfirst into the crush of water and logs.

“Pa?” Jamie stared at the place where his father had been.

Pete rushed across the dam to shore. He grabbed a peavey stick and sprinted along the bank down river, looking for his doomed comrade. Jamie, still glued to the dam, strained to watch, to hear. Pete raced around the bend, leaving Jamie to stare at the jam of logs which snagged and stacked haphazardly into a groaning mountain.

His pa had told him that the white pine had a spirit. It may only be a tree standing helpless as the lumberjacks slash their paths through the forests of Michigan with their axes and crosscut saws, but the spirit of a felled tree lives on, waiting to claim the life of a lumberjack.

PART ONE

FOX RIVER LOGGING CAMP

CHAPTER ONE

The Sluice Gate

Jamie.

He heard his pa’s voice, ghostly—a spirit, calling.

Jamie!

I’m coming Father. I can’t close the sluice gate, but I’m coming. Jamie watched the swirling vortex of water below him pounding against the jumble of logs. He felt his father’s spirit pulling him into the fierce rapids of the river.

“James Kangas, rise and shine.”

He could smell boiling coffee and the yeasty aroma of fresh-baked bread.

“Get up and wash your hands and face.”

His ma’s voice. Jamie opened his eyes a slit. He made out her silhouette in the dim kerosene light. She was still clad in widow’s black, as it had not yet been a year since the accident.

“Men will be in for breakfast. Get going, James, and set the table.”

Jamie sat up and stretched. His head throbbed and his legs were wobbly as he slid out of bed.

His ma cast a concerned look at him. “You’re not feeling poorly are you James?”

“No, Ma. Just a little stove up.”

“No wonder, all that running and fetching you do all day for the men.”

Jamie pulled his trousers and flannel shirt over his long johns. He shuffled his way to a pitcher perched on a stand and poured frigid water into a basin. He cupped his hands, scooped, and quickly splashed his face. The icy rivulets trickled down his neck and soaked his shirt. He shuddered.

“Hot water right here on the stove, son.”

“Like it cold,” muttered Jamie as he scrubbed his face with a piece of sacking. Truth was, he preferred hot, but Larry Flannigan had told him cold water would grow whiskers. Jamie was hoping for some sprouts before the end of winter. He couldn’t wait to boast the tangled beard sported by nearly all the lumberjacks—sometimes called jacks for short. He’d let the snuff he spat freeze in it too, like the men.

Jamie collected the cutlery and tin plates and cups and distributed them across a long, rough-hewn table. He felt his body going through the motions of his morning routine, but his mind was still at the river, the angry roar rising and drowning out the clink of plates and the hiss of flapjacks cooking on the stove.

If he’d been a man instead of a boy… It was a job for two stout men, not a job for a lad with arms like willow sticks.

“Jamie, help me.”

Pete and Jamie’s father had gone to open the sluice gate to start the spring drive. Jamie had come only to watch. But it all went wrong.

“Jamie!”

He snapped around. His ma stood watching him, tapping her foot.

“Yes, Ma’am?”

“Where were you, James? Looked like a hundred miles away.”

Jamie shrugged.

“Ring the dinner bell then help me with the bowls.”

Jamie stepped outside the mess hall and grabbed the leather thong that hung from the dinner bell clapper. A few sharp rings would bring the men for breakfast. Jamie went back inside and carried steaming bowls of beans and deer meat to the table. He heard the sounds of feet outside the mess hall door as the men stomped snow from their boots. The lumberjacks were coming—over thirty of them—each with an insatiable appetite.

“Hey boy,” shouted one jack, “that should do for me. What you gonna feed the rest of these fellas?”

Jamie heard his ma laugh as she marched up to the table and slapped down two heaping platters of hot flapjacks.

“Now, you gents sit your hides down and hush,” she said with mock scolding. “No talking at my table.”

The jacks knew she ruled her cook shack with an iron fist and muttered, “yes, Missus” and “right away, Ma’am.” Woe be to any man who showed up unwashed or forgot to remove his hat at her table. He was certain to be sent away to scrub up and find scant offerings by the time he could hurry back. Or in the case of a forgotten “sky piece,” the culprit’s hat would be snatched from his head by a disgusted Mrs. Kangas and his ears lightly boxed. Those who bowed their heads in a moment of silent grace were sure to gain the favor of the Widow Kangas. She’d see to it that his flaggin’s—his meal in the woods—was a little heartier than that of the heathen who simply dove into his grub without a word of thanks to his Maker. But as the foreman, Tom Haskins, had said, Anja Kangas whipped up the best chow this side of heaven and that made her more valuable than any sawyer or riverman. Any improprieties toward Jamie’s ma were met with immediate dismissal from the employment of the Chicago Lumber Company.

Jamie was another story. As chore boy he had the dubious honor of holding the lowest station in the logging camp and all for the paltry wages of a dollar fifty per week. Jamie was run ragged the next half hour bringing more platters and bowls of food and pouring gallons of coffee for the men. Next came the pies, still warm from the ovens, sliced into thick wedges and greedily devoured. There was no talking while the men ate, only the sound of utensils clinking and utterings of appreciation: “Fine eatin’ Missus. Chuck’s better’n the pay, that’s for sure.” At the end of the meal, the jacks rose from the table and filed out of the mess hall to begin their day’s work.

Only then did Jamie and his ma sit at the little table by the stove to eat their stack of flapjacks held back and kept warm under a towel. Next, Jamie helped his ma collect and scrape the plates, then wash the dishes in the tub full of steaming water. Some camp cooks didn’t bother with the washing, but Jamie’s ma lectured it was inviting disease to live in filth. The dishes done and stacked on their shelves, it was time for Jamie to start his day as chore boy, running to and fro with messages and food and, much more to his liking, helping the teamsters with their fine teams of horses.

Already his ma was cutting thick slices of bread and meat in preparation of the mid-day meal. She pulled a time piece from her apron pocket and studied it.

“Not bad, James, got breakfast behind us, and it’s nary five thirty. Dawn should come soon. Getting light out earlier with spring coming.”

Jamie nodded as he pulled his Mackinaw coat and wool hat off the peg next to his bed.

“Remember your schooling,” she said, slipping the watch back into her apron.

“Yes Ma’am,” Jamie said. He was required to spend an hour each afternoon, when light was best, practicing his ciphering and spelling and reading Bible verse.

Jamie slipped out into the snowy woods and headed for the stable to help with the harnessing. In twelve hours, it would be dark again. Then, after supper dishes, he would crawl under a pile of wool blankets onto his straw-stuffed mattress. Exhausted, he would soon sleep and the dream would torment him again. Only this time it would be different. This time he would dream of the man, James Kangas who, singlehandedly, would close the sluice gate.

CHAPTER TWO

An Eye For An Eye

The pleasant aroma of his ma’s cooking was soon replaced by the pungent odor of the stable. Jamie didn’t mind, though. He liked the horses and the smells and noises associated with them: The nickering and occasional impatient stamping of a hoof at feeding time and the popping noises their lips made when they skimmed hay chaff from the manger. The crude stable held twelve horses, or six teams. Three men worked the horses, each responsible for two teams, which they rotated. Jamie admired the gentleness of the burly teamsters as they coaxed and sweet-talked their charges through the day’s work. And hard work it was for the beasts straining against their collars, pulling the skids from the forest to the riverbank where the logs were stacked. Jamie often watched in awe as a lumberjack sky-hooked the logs into an impossibly high pyramid on the skid.

It was the job of a chore boy to help where help was needed.

“Come here, boy, and untangle these traces,” hollered one of the men.

“Hold Molly still, will you, son!” shouted another.

Jamie rushed about in a frenzy helping with buckles, adjusting bridles, and steadying the horses as they were harnessed.

“Say, Jamie, I think Max has a loose shoe. Lift up his rear right hoof for me while I get a crimper. Mind you don’t let that hoof down ‘til I say. Horse moves just right, he’ll cut himself with that loose shoe.”

Jamie hurried to obey the teamster, Larry Flannigan. Jamie bent and lifted the hoof in question, squinting at the studded shoe. He tried to wriggle the shoe but it didn’t budge. Well, Jamie thought, Flannigan knows what he’s doing. He wondered, though, why it was taking so long to fetch a crimper. The smithy’s shed was just through the door. Jamie’s back soon began to protest and the horse, Max, who never missed an opportunity to rest, shifted a goodly portion of his bulk onto the boy. Soon Jamie’s legs ached along with his neck and his arms were going numb with the strain.

“Where you ‘spose Mr. Flannigan got to?” Jamie asked. But the other men were moving their teams out the doors into the dim light of the dawn.

“Mr. Flannigan?”

Well, he’d show them that he was no slacker. He’d hold this hoof until spring thaw if need be. Jamie shifted his position, moving from the side of Max’s rear end directly under his tail. There, that was better.

Jamie felt a subtle shift in the horse as he lifted his tail. Before he could react, he felt the warmth and smelled the distinct aroma of manure as it plopped on the back of his neck.

“Hell and damnation!” he shouted. Ma forbid him to cuss, but it just slipped out. He dropped the hoof with a thud and tried to wipe himself clean with a handful of straw. Jamie nearly gagged up his breakfast when he felt a ball of the stuff work its way down his neck. Ma would be furious! She would make him launder his clothes and he would have no choice but to submit to an all-over scrubbing, ahead of the normal springtime ritual.

Larry Flannigan silhouetted the doorway, hands on hips, legs spread, and head thrown back with a roar of laughter. Max whinnied, a horse’s laugh if Jamie ever heard one. Some of the jacks came around to see what the ruckus was and joined in the sport.

“Got you with the loose shoe prank, huh boy? You really thought you had to hold up that hoof just ‘cause the shoe was loose?”

“C’mere, will ya? I gotta pair of socks you need to hold up ‘til they dry. Don’t let’em touch the ground now lad, or you’ll have to wash them and start all over. Har har!”

Jamie felt his checks flush. He stripped off his shirt, making further spectacle of himself by exposing his runty torso. This brought more jeers and rude comments from the men. Finally, freeing his clothing of the manure, he redressed and pushed past his tormentors through the door.

Jamie’s cheeks, laced with tears, stung in the cold air. He took refuge in the privy, sitting over the hole with his drawers still up. In spite of the cold, the blended odors of the privy and the horse manure were strong and again Jamie fought to keep his breakfast down. He hunched in a ball clutching his knees and wept. Tears dropped and froze to the scarred floor.

“Jamie lad.”

Somebody was rapping on the door.

“Go away,” Jamie said. “I’m busy.”

“Now come on James. The men were only having some fun. Come on out of there ‘fore you choke on the fumes.”

Jamie recognized the voice. It was Pete Atkins, the riverman on the sluice gate. He was also a teamster in the winter.

“Just leave me alone.” Jamie hated the sound of his shrill, boyish voice.

“Now, son, fellas wouldn’t tease ya so if they didn’t like ya.”

Jamie mulled on this for a while. He uncoiled his body and reached to crack the door. “Don’t make sense to me,” Jamie said through the door slit. “Somebody likes a body, why would they cause him misery?”

“Because they’re a bunch of hooligans, that’s why. Don’t know any better. Way I see it, best thing to do is show them how much you like them—so to speak.”

“Right now, I don’t like ‘em much.” Jamie stood and slipped out of the privy into the fresh air. He took a deep, ragged breath. “Course, I don’t hate ‘em or anything.”

“Naw, not Christian-like to hate. But the Lord wouldn’t mind a little of that eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth thing.”

Jamie had read that Bible passage. He had also heard about turning the other cheek. It was a little confusing, but he expected it depended on the situation. Right now the eye for an eye suited him. He’d like to thrash Larry Flannigan then and there, make him bleed. But Jamie knew the powerful Flannigan, famous for his brawling, would squash him like an overripe grape.

Pete put his arm around Jamie’s shoulders and they walked back to the stable. Jamie’s next task of the day was to muck out the barn and brush the teams who were enjoying their day off. Maybe he could tell his ma that he had aimed badly with a pitchfork and got some droppings down his shirt. It would be a fib but that was probably better than betraying the jacks by telling the truth. That would be breaking the code of a lumberjack.

“Now listen here boy, you get to thinkin’ about this and let me know if I can help. I owe Flannigan one or two myself.”

Jamie nodded and cracked a smile.

Pete smiled back and headed out the door. He hesitated and turned around, his mouth opening as if to say something. Jamie waited, expectantly.

“You reckon your ma will be making up deer meat sandwiches for our flaggin’s?’

“No, sir, I think it’s gonna be ham slabs and butter today. Baked the bread fresh this morning. Got some canned peaches, too. ‘course may not be enough to go around of the peaches.”

Pete nodded. “I’ll be in the north quarter, sprinkling. Why don’t you ride the Swede out today? He could use the exercise.”

Jamie felt his heart lighten. The Swede was half of Pete’s second team. Ride the Swede!

He was a grand horse with a dun coat and black points. Most of the horses were ordinary brown or black. Swede’s harness mate, Viking, had come up lame, and the Swede had not been under harness for a week. Pete was using his other team to pull the sprinkler sled used to ice the road so the log sleds would glide easier.

“I’m obliged.”

“You take good care of him. I expect you to liniment Viking up and hand walk him.”

“Yes sir!”

“And I expect peaches with my flaggin’s!”

“Yes sir!”

“And Jamie—”

“Yes sir?”

“Call me Pete. Never been comfortable with sir, even from a sapling like you.”

“Yes—okay Pete.”

Pete gave a curt nod and went out of the barn to his team. He climbed on the sprinkler wagon, picked up the lines and clucked to the horses. Jamie could hear the horseshoe calks crunching along the packed snow and ice.

Jamie grabbed a pitchfork and set to work. The pitchfork felt lighter than usual as he flung the soiled straw onto the manure sled. While he worked, he thought about his straw mattress and how good it felt when it was bulging with fresh stuffing. Every week, Jamie would turn the mattress and give it a shake to plump it up. When the straw could no longer be revived, his ma would tear out the end seam on the mattress and they would replace the old straw with fresh. His ma would then re-sew the end. Some of the jacks did this as well, while others seemed content to sleep on a crushed and flattened mattress which could do little to cushion them from the hard, knobby boards of their bunks.

Jamie stared at the pile of soiled straw. This wasn’t even fit for horses to sleep on, he thought. Jamie’s smile turned to a smirk. If his ma saw his face, she would know instantly that he was up to mischief. But she wasn’t there and the bit of mischief that Jamie was contemplating conformed to the teachings of her Bible. The eye for an eye part, anyway.

Jamie paused for a moment after entering the men’s bunkhouse, trying to adjust his vision in the dark, windowless building. He fumbled through the shadows with only a slit of light spilling from the cracked door and a dim glow from the iron stove to guide him. Where was Flannigan’s bunk? Something wet slapped him in the face. He tried to duck away and was nearly strangled by a rope that caught under his chin. Reeling backwards, Jamie crashed into a table, almost upsetting a kerosene lamp. Heart hammering, he felt along the tabletop until his fingers closed around a matchbox. With shaky hands, Jamie removed a match and struck it across the rough tabletop. For a brief moment, the room was illuminated by the tiny flame. Jamie lifted the chimney from the lamp and lit the wick, then shook out the match. He replaced the chimney, lifted the lamp and moved it around surveying the room. The chimney clattered softly in his unsteady hand. He soon found the source of the soggy slap in the face and attempted strangulation. A rope, hung with drying long johns and socks, had been strung from a bunk post to a rafter. One pair of woollies had been knocked askew and seemed to be clinging for life by one arm.

Carrying the lamp, Jamie moved along the bunks looking for a clue indicating which one was Flannigan’s. Obviously, they didn’t have names on them. Some of the bunks were tidy, blankets folded, extra clothing draped neatly over railings. Others resembled pig sties, blankets rumpled, clothing and meager personal items strewn about. Without fail, each bunk had several wool Hudson Bay blankets. The number of black stripes, or points, indicated the number of beaver pelts required in trade. Jamie remembered Flannigan bragging about his five-point blanket—the only one in camp.

Moving quickly, Jamie worked his way through the thirty bunks. There were a lot of three-point blankets, half-dozen four-pointers, some boasting colorful stripes and some plain. But where was Flannigan’s prided five-point? Just as Jamie was about to give up the lamp glow washed over an upper bunk, which was a mess but for a neatly folded blanket. He reached up, lifted a corner, and counted. Five stripes!

Jamie had to set the lamp back on the table to drag the mattress off the top bunk. How could straw be so heavy? With a final heave, it slid off its wooden slats and like a demon seemed to throw itself against Jamie, knocking him off balance so that he sat abruptly on the hard floor. Sweat beaded his brow as he dragged the mattress to the door. He paused, trying to catch his breath, which rasped like a sawyer’s blade. Outside he squinted in the daylight. It was well into the morning, though the sun could not penetrate the veil of clouds that hung over camp. It was getting late.

His urgency was turning to panic as he fought to unseam the mattress. If only he had thought to bring a knife. He must hurry or he would be caught. Ma would come out of the cook shack and see her demented son wrestling with, of all things, a mattress. Or one of the lumberjacks would return to camp to patch up an injury or repair an axe and catch Jamie. What a strange sight indeed! There he would be, boy idiot, chewing on the end of a mattress, the presence of his manure sled heaped with its steaming load adding to the mystery.

Sweat ran in rivulets down Jamie’s spine as he bit and chewed at the mattress end. At last, the course thread gave way and he quickly spilled its contents onto the manure sled. Filling the mattress with the soiled straw could not be done with a pitchfork, as Jamie had planned, for the limp material of the mattress would not stand open, but simply collapsed into itself. Jamie would have to stuff the mattress by hand! He contemplated the unsavory task for a moment. If only he had spare gloves or even mittens—a long mitten that would reach to his elbow, like socks that came up to the knees. That was it: a sock! Jamie raced into the bunkhouse, yanked a sock off the clothesline and pulled it over his arm. Sufficiently protected, Jamie returned to the mattress caper. By holding the mattress open with one hand and stuffing with the other, the ticking was soon bulging with fresh manure and soiled straw.

He had not been able to filch a needle and thread from his ma’s sewing box, so he had no way to sew the mattress back up. No matter, he would tuck it under.

Jamie ripped off the protective sock/mitten and threw it behind the bunkhouse. He grabbed the open end of the mattress and dragged it, like an overloaded flour sack, back into the bunkhouse. He gasped for air, his chest on the verge of exploding. Many layers below his coat, his drenched long johns clung to his legs, resisting his every step. At last he reached Flannigan’s bunk and stopped dead. He craned his neck looking up. What was he thinking? He might as well try to hoist the mattress up a pine tree! It was no use. He had been outwitted by his own plan. Jamie dropped to his knees and with clenched fists pummeled the manure-stuffed mattress. Why was everything so hard? Why wasn’t his pa there to help? Pa, so strong—muscles bulging through his long johns—would have hoisted the mattress without breaking a sweat. But the river had taken him, swallowed him like a huge serpent, and all those muscles were no match for the current and the logs that churned in the deadly brew. And Jamie had done nothing, nothing but stand by weak and helpless as a newborn fawn.

A clanging noise bolted Jamie upright. Ma was calling him with the dinner bell to deliver the flaggin’s to the men. He stared at the mattress. Sinister, it taunted him. Weakling and dimwit, defeated by a brainless mattress filled with horse dung.

CHAPTER THREE

Flagging’s

The Swede’s plump back and thick winter coat gave Jamie the sensation he was riding on a cloud. His ma had wrapped and packed sandwiches and canned fruit into haversacks which were then tied across the Swede’s back for carrying to the lumberjacks. Also tucked away were tins of tea for brewing hot drinks in the number-two soup cans that each jack carried hooked onto his suspender button. Jamie rode down the pike-way to his first destination. He tried to savor the ride. He loved the gentle, rhythmic swaying of the big horse’s gait. But the fact that Flannigan’s mattress still lay in a heap back on the bunkhouse floor could not be shoved into the back of his mind. In the distance, he heard the sharp crack of a tree yielding to the sawyer’s blade. Timber! reverberated through the forest, followed by more cracking and snapping as a mighty pine plummeted to earth, its branches and massive trunk ripping away that which stood in its path.

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)