0,99 €

0,99 €

oder

-100%

Sammeln Sie Punkte in unserem Gutscheinprogramm und kaufen Sie E-Books und Hörbücher mit bis zu 100% Rabatt.

Mehr erfahren.

Mehr erfahren.

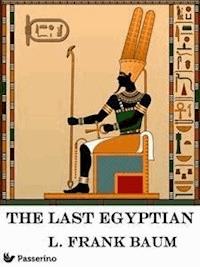

- Herausgeber: Passerino

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The Last Egyptian: A Romance of the Nile is a novel written by L. Frank Baum, famous as the creator of the Land of Oz. L. Frank Baum (1856 - 1919) was an American author chiefly famous for his children's books, particularly The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and its sequels

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

0,0

Bewertungen werden von Nutzern von Legimi sowie anderen Partner-Webseiten vergeben.

Legimi prüft nicht, ob Rezensionen von Nutzern stammen, die den betreffenden Titel tatsächlich gekauft oder gelesen/gehört haben. Wir entfernen aber gefälschte Rezensionen.

Ähnliche

The sky is the limit

ISBN: 9788893454278

This ebook was created with StreetLib Writehttp://write.streetlib.com

Table of contents

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 1

WHERE THE DESERT MEETS THE NILE.

The sun fell hot upon the bosom

of the Nile and clung there, vibrant, hesitating, yet aggressive,

as if baffled in its desire to penetrate

beneath the river’s lurid surface. For the Nile defies the sun, and

relegates him to his own broad domain, wherein his power is

undisputed.

On either side the broad stream humanity shrank from Ra’s seething

disc.

The shaduf workers had abandoned their skin-covered buckets and

bamboo

poles to seek shelter from the heat beneath a straggling tree or a

straw

mat elevated on stalks of ripe sugar-cane. The boats of the

fishermen

lay in little coves, where the sails were spread as awnings to

shade

their crews. The fellaheen laborers had all retired to their clay

huts

to sleep through this fiercest period of the afternoon heat.

On the Nile, however, a small steam dahabeah puffed lazily along,

stemming with its slow motion the sweep of the mighty river toward

the

sea. The Arab stoker, naked and sweating, stood as far as possible

from

the little boiler and watched it with a look of absolute repulsion

upon

his swarthy face. The engineer, also an Arab, lay stretched upon

the

deck half asleep, but with both ears alert to catch any sound that

might

denote the fact that the straining, rickety engine was failing to

perform its full duty. Back of the tiny cabin sat the dusky

steersman,

as naked and inert as his fellows, while under the deck awning

reclined

the one white man of the party, a young Englishman clothed in khaki

knickerbockers and a white silk shirt well open at the throat.

There were no tourists in Egypt at this season. If you find a white

man

on the Nile in April, he is either attached to some exploration

party

engaged in excavations or a government employee from Cairo, Assyut

or

Luxor, bent upon an urgent mission.

The dahabeah was not a government boat, though, so that our

Englishman

was more likely to be an explorer than an official. It was evident

he

was no stranger to tropical climes, if we judged by his sun-browned

skin

and the quiet resignation to existing conditions with which he

puffed

his black briar and relaxed his muscular frame. He did not sleep,

but

lay with his head upon a low wicker rest that enabled him to sweep

the

banks of the Nile with his keen blue eyes.

The three Arabs regarded their master from time to time with

stealthy

glances, in which wonder was mingled with a certain respect. The

foreigner was a fool to travel during the heat of the day; no doubt

of

that at all. The native knows when to work and when to sleep--a

lesson

the European never learns. Yet this was no casual adventurer

exploiting

his folly, but a man who had lived among them for years, who spoke

Arabic fluently and could even cipher those hieroglyphics of the

dead

ages which abound throughout modern Egypt. Hassan, Abdallah and Ali

knew

this well, for they had accompanied Winston Bey on former

expeditions,

and heard him translate the ugly signs graven upon the ugly stones

into

excellent Arabic. It was all very wonderful in its way, but quite

useless and impractical, if their opinion were allowed. And the

master

himself was impractical. He did foolish things at all times, and

sacrificed his own comfort and that of his servants in order to

accomplish unnecessary objects. Had he not paid well for his whims,

Winston Bey might have sought followers in vain; but the Arab will

even

roast himself upon the Nile on an April afternoon to obtain the

much-coveted gold of the European.

At four o’clock a slight breeze arose; but what matter? The journey

was

nearly done now. They had rounded a curve in the river, and ahead

of

them, lying close to the east bank, were the low mountains of Gebel

Abu

Fedah. At the south, where the rocks ended abruptly, lay a small

grove

of palms. Between the palms and the mountains was the beaten path

leading from the Nile to the village of Al-Kusiyeh, a mile or so

inland,

which was the particular place the master had come so far and so

fast to

visit.

The breeze, although hardly felt, served to refresh the enervated

travelers. Winston sat up and knocked the ashes from his pipe,

making a

careful scrutiny at the same time of the lifeless landscape ahead.

The mountains of gray limestone looked very uninviting as they lay

reeking under the terrible heat of the sun. From their base to the

river

was no sign of vegetation, but only a hardened clay surface. The

desert

sands had drifted in in places. Even under the palms it lay in

heavy

drifts, for the land between the Nile and Al-Kusiyeh was abandoned

to

nature, and the fellaheen had never cared to redeem it.

The water was deep by the east bank, for the curve of the river

swept

the current close to the shore. The little dahabeah puffed noisily

up to

the bank and deposited the Englishman upon the hard clay. Then it

backed

across into shallow water, and Hassan shut down the engine while

Abdallah dropped the anchor.

Winston now wore his cork helmet and carried a brown umbrella lined

with

green. With all his energy, the transition from the deck of the

dahabeah

to this oven-like atmosphere of the shore bade fair to overcome his

resolution to proceed to the village.

But it would never do to recall his men so soon. They would

consider it

an acknowledgment that he had erred in judgment, and the only way

to

manage an Arab is to make him believe you know what you are about.

The

palm trees were not far away. He would rest in their shade until

the sun

was lower.

A dozen steps and the perspiration started from every pore. But he

kept

on, doggedly, until he came to the oblong shadow cast by the first

palm,

and there he squatted in the sand and mopped his face with his

handkerchief.

The silence was oppressive. There was no sound of any kind to

relieve

it. Even the beetles were hidden far under the sand, and there was

no

habitation near enough for a donkey’s bray or a camel’s harsh growl

to

be heard. The Nile flows quietly at this point, and the boat had

ceased

to puff and rattle its machinery.

Winston brushed aside the top layer of sand with his hands, for

that

upon the surface was so hot that contact with it was unbearable.

Then he

extended his body to rest, turning slightly this way and that to

catch

in his face the faint breath of the breeze that passed between the

mountains and the Nile. At the best he was doomed to an

uncomfortable

hour or two, and he cast longing glances at the other bits of shade

to

note whether any seemed more inviting than the one he had selected.

During this inspection his eye caught a patch of white some

distance

away. It was directly over the shadow of the furthest tree of the

group,

and aroused his curiosity. After a minute he arose in a leisurely

fashion and walked over to the spot of white, which on nearer

approach

proved to be a soiled cotton tunic or burnous. It lay half buried

in the

sand, and at one end were the folds of a dirty turban, with faded

red

and yellow stripes running across the coarse cloth.

Winston put his foot on the burnous and the thing stirred and

emitted a

muffled growl. At that he kicked the form viciously; but now it

neither

stirred nor made a sound. Instead, a narrow slit appeared between

the

folds of the turban, and an eye, black and glistening, looked

steadfastly upon the intruder.

“Do you take me for a beast, you imbecile, that you dare to disturb

my

slumbers?” asked a calm voice, in Arabic.

The heat had made Winston Bey impatient.

“Yes; you are a dog. Get up!” he commanded, kicking the form again.

The turban was removed, disclosing a face, and the man sat up,

crossing

his bare legs beneath him as he stared fixedly at his persecutor.

Aside from the coarse burnous, sadly discolored in many places, the

fellow was unclothed. His skin showed at the breast and below his

knees,

and did not convey an impression of immaculate cleanliness. Of

slender

build, with broad shoulders, long hands and feet and sinewy arms

and

legs, the form disclosed was curiously like those so often

presented in

the picture-writing upon the walls of ancient temples. His forehead

was

high, his chin square, his eyes large and soft, his cheeks full,

his

mouth wide and sensual, his nose short and rounded. His jaws

protruded

slightly and his hair was smooth and fine. In color the tint of his

skin was not darker than the tanned cuticle of the Englishman, but

the

brown was softer, and resembled coffee that has been plentifully

diluted

with cream. A handsome fellow in his way, with an expression rather

unconcerned than dignified, which masked a countenance calculated

to

baffle even a shrewder and more experienced observer than Winston

Bey.

Said the Englishman, looking at him closely:

“You are a Copt.”

Inadvertently he had spoken in his mother tongue and the man

laughed.

“If you follow the common prejudice and consider every Copt a

Christian,” he returned in purest English, “then I am no Copt; but

if

you mean that I am an Egyptian, and no dog of an Arab, then,

indeed, you

are correct in your estimate.”

Winston uttered an involuntary exclamation of surprise. For a

native to

speak English is not so unusual; but none that he knew expressed

himself

with the same ease and confidence indicated in this man’s reply. He

brushed away some of the superheated sand and sat down facing his

new

acquaintance.

“Perhaps,” said he--a touch of sarcasm in his voice--“I am speaking

with

a descendant of the Great Rameses himself.”

“Better than that,” rejoined the other, coolly. “My forefather was

Ahtka-Rā, of true royal blood, who ruled the second Rameses as

cleverly

as that foolish monarch imagined he ruled the Egyptians.”

Winston seemed amused.

“I regret,” said he, with mock politeness, “that I have never

before

heard of your great forefather.”

“But why should you?” asked the Egyptian. “You are, I suppose, one

of

those uneasy investigators that prowl through Egypt in a stupid

endeavor

to decipher the inscriptions on the old temples and tombs. You can

read

a little--yes; but that little puzzles and confuses you. Your most

learned scholars--your Mariettes and Petries and Masperos--discover

one

clue and guess at twenty, and so build up a wonderful history of

the

ancient kings that is absurd to those who know the true records.”

“Who knows them?” asked Winston, quickly.

The man dropped his eyes.

“No one, perhaps,” he mumbled. “At the best, but one or two. But

you

would know more if you first studied the language of the ancient

Egyptians, so that when you deciphered the signs and picture

writings

you could tell with some degree of certainty what they meant.”

Winston sniffed. “Answer my question!” said he, sternly. “Who knows

the

true records, and where are they?”

“Ah, I am very ignorant,” said the other, shaking his head with an

humble expression. “Who am I, the poor Kāra, to dispute with the

scholars of Europe?”

The Englishman fanned himself with his helmet and sat silent for a

time.

“But this ancestor of yours--the man who ruled the Great

Rameses--who

was he?” he asked, presently.

“Men called him Ahtka-Rā, as I said. He was descended from the

famous

Queen Hatshepset, and his blood was pure. Indeed, my ancestor

should

have ruled Egypt as its king, had not the first Rameses overthrown

the

line of Mēnēs and established a dynasty of his own. But Ahtka-Rā,

unable

to rule in his own name, nevertheless ruled through the weak

Rameses,

under whom he bore the titles of High Priest of Āmen, Lord of the

Harvests and Chief Treasurer. All of the kingdom he controlled and

managed, sending Rameses to wars to keep him occupied, and then,

when

the king returned, setting him to build temples and palaces, and to

erect monuments to himself, that he might have no excuse to

interfere

with the real business of the government. You, therefore, who read

the

inscriptions of the vain king wonder at his power and call him

great;

and, in your ignorance, you know not even the name of Ahtka-Rā, the

most

wonderful ruler that Egypt has ever known.”

“It is true that we do not know him,” returned Winston,

scrutinizing the

man before him with a puzzled expression. “You seem better informed

than

the Egyptologists!”

Kāra dipped his hands into the sand beside him and let the grains

slip

between his fingers, watching them thoughtfully.

“Rameses the Second,” said he, “reigned sixty-five years, and--”

“Sixty-seven years,” corrected Winston. “It is written.”

“In the inscriptions, which are false,” explained the Egyptian. “My

ancestor concealed the death of Rameses for two years, because

Meremptah, who would succeed him, was a deadly enemy. But Meremptah

discovered the secret at last, and at once killed Ahtka-Rā, who was

very

old and unable to oppose him longer. And after that the treasure

cities

of Pithom and Raamses, which my ancestor had built, were seized by

the

new king, but no treasures were found in them. Even in death my

great

ancestor was able to deceive and humble his enemies.”

“Listen, Kāra,” said Winston, his voice trembling with suppressed

eagerness; “to know that which you have told to me means that you

have

discovered some sort of record hitherto unknown to scientists. To

us who

are striving to unravel the mystery of ancient Egyptian history

this

information will be invaluable. Let me share your knowledge, and

tell me

what you require in exchange for your secret. You are poor; I will

make

you rich. You are unknown; I will make the name of Kāra famous. You

are

young; you shall enjoy life. Speak, my brother, and believe that I

will

deal justly by you--on the word of an Englishman.”

The Egyptian did not even look up, but continued playing with the

sand.

Yet over his grave features a smile slowly spread.

“It is not five minutes,” he murmured softly, “since I was twice

kicked

and called a dog. Now I am the Englishman’s brother, and he will

make me

rich and famous.”

Winston frowned, as if he would like to kick the fellow again. But

he

resisted the temptation.

“What would you?” he asked, indifferently. “The burnous might mean

an

Arab. It is good for the Arab to be kicked at times.”

Possibly Kāra neither saw the jest nor understood the apology. His

unreadable countenance was still turned toward the sand, and he

answered

nothing.

The Englishman moved uneasily. Then he extracted a cigarette case

from

his pocket, opened it, and extended it toward the Egyptian.

Kāra looked at the cigarettes and his face bore the first

expression of

interest it had yet shown. Very deliberately he bowed, touched his

forehead and then his heart with his right hand, and afterward

leaned

forward and calmly selected a cigarette.

Winston produced a match and lighted it, the Egyptian’s eyes

seriously

following his every motion. He applied the light to his own

cigarette

first; then to that of Kāra. Another touch of the forehead and

breast

and the native was luxuriously inhaling the smoke of the tobacco.

His

eyes were brighter and he wore a look of great content.

The Englishman silently watched until the other had taken his third

whiff; then, the ceremonial being completed, he spoke, choosing his

words carefully.

“Seek as we may, my brother, for the records of the dead

civilization of

your native land, we know full well that the most important

documents

will be discovered in the future, as in the past, by the modern

Egyptians themselves. Your traditions, handed down through many

generations, give to you a secret knowledge of where the important

papyri and tablets are deposited. If there are hidden tombs in

Gebel Abu

Fedah, or near the city of Al-Kusiyeh, perhaps you know where to

find

them; and if so, we will open them together and profit equally by

what

we secure.”

The Egyptian shook his head and flicked the ash from his cigarette

with

an annoyed gesture.

“You are wrong in estimating the source of my knowledge,” said he,

in a

tone that was slightly acrimonious. “Look at my rags,” spreading

his

arms outward; “would I refuse your bribe if I knew how to earn it?

I

have not smoked a cigarette before in months--not since Tadros the

dragoman came to Al Fedah in the winter. I am barefoot, because I

fear

to wear out my sandals until I know how to replace them. Often I am

hungry, and I live like a jackal, shrinking from all intercourse

with my

fellows or with the world. That is Kāra, the son of kings, the

royal

one!”

Winston was astonished. It is seldom a native complains of his lot

or

resents his condition, however lowly it may be. Yet here was one

absolutely rebellious.

“Why?” he asked.

“Because my high birth isolates me,” was the reply, with an accent

of

pride. “It is no comfortable thing to be Kāra, the lineal

descendant of

the great Ahtka-Rā, in the days when Egypt’s power is gone, and her

children are scorned by the Arab Muslims and buffeted by the

English

Christians.”

“Do you live in the village?” asked Winston.

“No; my burrow is in a huddle of huts behind the mountain, in a

place

that is called Fedah.”

“With whom do you live?”

“My grandmother, Hatatcha.”

“Ah!”

“You have heard of her?”

“No; I was thinking only of an Egyptian Princess Hatatcha who set

fashionable London crazy in my father’s time.”

Kāra leaned forward eagerly, and then cast a half fearful glance

around,

at the mountains, the desert, and the Nile.

“Tell me about her!” he said, sinking his voice to a whisper.

“About the Princess?” asked Winston, surprised. “Really, I know

little

of her history. She came in a flash of wonderful oriental

magnificence,

I have heard, and soon had the nobility of England suing for her

favors.

Lord Roane especially divorced his wife that he might marry the

beautiful Egyptian; and then she refused to wed with him. There

were

scandals in plenty before Hatatcha disappeared from London, which

she

did as mysteriously as she had come, and without a day’s warning. I

remember that certain infatuated admirers spent fortunes in search

of

her, overrunning all Egypt, but without avail. No one has ever

heard of

her since.”

Kāra drew a deep breath, sighing softly.

“It was like my grandmother,” he murmured. “She was always a

daughter of

Set.”

Winston stared at him.

“Do you mean to say--” he began.

“Yes,” whispered Kāra, casting another frightened look around; “it

was

my grandmother, Hatatcha, who did that. You must not tell, my

brother,

for she is still in league with the devils and would destroy us

both if

she came to hate us. Her daughter, who was my mother, was the child

of

that same Lord Roane you have mentioned; but she never knew her

father

nor England. I myself have never been a day’s journey from the

Nile, for

Hatatcha makes me her slave.”

“She must be very old, if she still lives,” said Winston, musingly.

“She was seventeen when she went to London,” replied Kāra, “and she

returned here in three years, with my mother in her arms. Her

daughter

was thirty-five when I was born, and that is twenty-three years

ago.

Fifty-eight is not an advanced age, yet Hatatcha was a withered hag

when first I remember her, and she is the same to-day. By the head

of

Osiris, my brother, she is likely to live until I am stiff in my

tomb.”

“It was she who taught you to speak English?”

“Yes. I knew it when I was a baby, for in our private converse she

has

always used the English tongue. Also I speak the ancient Egyptian

language, which you call the Coptic, and I read correctly the

hieroglyphics and picture-writings of my ancestors. The Arabic, of

course, I know. Hatatcha has been a careful teacher.”

“What of your mother?” asked Winston.

“Why, she ran away when I was a child, to enter the harem of an

Arab in

Cairo, so that she passed out of our lives, and I have lived with

my

grandmother always.”

“I am impressed by the fact,” said the Englishman, with a sneer,

“that

your royal blood is not so pure after all.”

“And why not?” returned Kāra, composedly. “Is it not from the

mother we

descend? Who my grandfather may have been matters little, provided

Hatatcha, the royal one, is my granddame. Perhaps my mother never

considered who my father might be; it was unimportant. From her I

drew

the blood of the great Ahtka-Rā, who lives again in me. Robbed of

your

hollow ceremonial of marriage, you people of Europe can boast no

true

descent save through your mothers--no purer blood than I, ignoring

my

fathers, am sure now courses in my veins; for the father, giving so

little to his progeny, can scarcely contaminate it, whatever he may

chance to be.”

The other, paying little heed to this discourse, the platitudes of

which

were all too familiar to his ears, reflected deeply on the strange

discovery he had made through this unconventional Egyptian.

“Then,” said he, pursuing his train of thought, “your knowledge of

your

ancestry and the life and works of Ahtka-Rā was obtained through

your

grandmother?”

“Yes.”

“And she has not disclosed to you how it is that she knows all

this?”

“No. She says it is true, and I believe it. Hatatcha is a wonderful

woman.”

“I agree with you. Where did she get the money that enabled her to

amaze

all England with her magnificence and splendor?”

“I do not know.”

“Is she wealthy now?”

Kāra laughed.

“Did I not say we were half starved, and live like foxes in a hole?

For

raiment we have each one ragged garment. But the outside of man

matters

little, save to those who have nothing within. Treasures may be

kept in

a rotten chest.”

“But personally you would prefer a handsome casket?”

“Of course. It is Hatatcha who teaches me philosophy to make me

forget

my rags.”

The Englishman reflected.

“Do you labor in the fields?” he asked.

“She will not let me,” said Kāra. “If my wrongs were righted, she

holds,

I would even now be king of Egypt. The certainty that they will

never be

righted does not alter the morale of the case.”

“Does Hatatcha earn money herself?”

“She sits in her hut morning and night, muttering curses upon her

enemies.”

“Then how do you live at all?”

Kāra seemed surprised by the question, and considered carefully his

reply.

“At times,” said he, “when our needs are greatest, my grandmother

will

produce an ancient coin of the reign of Hystaspes, which the sheik

at

Al-Kusiyeh readily changes into piasters, because they will give

him a

good premium on it at the museum in Cairo. Once, years ago, the

sheik

threatened Hatatcha unless she confessed where she had found these

coins; but my grandmother called Set to her aid, and cast a spell

upon

the sheik, so that his camels died of rot and his children became

blind.

After that he let Hatatcha alone, but he was still glad to get her

coins.”

“Where does she keep them?”

“It is her secret. When she was ill, a month ago, and lay like one

dead,

I searched everywhere for treasure and found it not. Perhaps she

has

exhausted her store.”

“Had she anything besides the coins?”

“Once a jewel, which she sent by Tadros, the dragoman, to exchange

for

English books in Cairo.”

“What became of the books?”

“After we had both read them they disappeared. I do not know what

became

of them.”

They had shifted their seats twice, because the shadow cast by the

palms

moved as the sun drew nearer to the horizon. Now the patches were

long

and narrow, and there was a cooler breath in the air.

The Englishman sat long silent, thinking intently. Kāra was

placidly

smoking his third cigarette.

The rivalry among excavators and Egyptologists generally is

intense. All

are eager to be recognized as discoverers. Since the lucky find of

the

plucky American, Davis, the explorers among the ancient ruins of

Egypt

had been on the qui vive to unearth some farther record of

antiquity to

startle and interest the scholars of the world. Much of value has

been

found along the Nile banks, it is true; but it is generally

believed

that much more remains to be discovered.

Gerald Winston, with a fortune at his command and a passion for

Egyptology, was an indefatigable prospector in this fascinating

field,

and it was because of a rumor that ancient coins and jewels had

come

from the Sheik of Al-Kusiyeh that he had resolved to visit that

village

in person and endeavor to learn the secret source of this wealth

before

someone else forestalled him.

The story that he had just heard from the lips of the voluble Kāra

rendered his visit to Al-Kusiyeh unnecessary; but that he was now

on the

trail of an important discovery was quite clear to him. How best to

master the delicate conditions confronting him must be a subject of

careful consideration, for any mistake on his part would ruin all

his

hopes.

“If my brother obtains any further valuable knowledge,” said he,

finally, “he will wish to sell it to good advantage. And it is

evident

to both of us that old Hatatcha has visited some secret tomb, from

whence she has taken the treasure that enabled her to astound

London for

a brief period. When her wealth was exhausted she was forced to

return

to her squalid surroundings, and by dint of strict economy has

lived

upon the few coins that remained to her until now. Knowing part of

your

grandmother’s story, it is easy to guess the remainder. The coins

of

Darius Hystaspes date about five hundred years before Christ, so

that

they would not account for Hatatcha’s ample knowledge of a period

two

thousand years earlier. But mark me, Kāra, the tomb from which your

grandmother extracted such treasure must of necessity contain much

else--not such things as the old woman could dispose of without

suspicion, but records and relics which in my hands would be

invaluable,

and for which I would gladly pay you thousands of piasters. See

what you

can do to aid me to bring about this desirable result. If you can

manage

to win the secret from your grandmother, you need be her slave no

longer. You may go to Cairo and see the dancing girls and spend

your

money freely; or you can buy donkeys and a camel, and set up for a

sheik. Meantime I will keep my dahabeah in this vicinity, and every

day

I will pass this spot at sundown and await for you to signal me. Is

it

all clear to you, my brother?”

“It is as crystal,” answered the Egyptian gravely.

He took another cigarette, lighted it with graceful composure, and

rose

to his feet. Winston also stood up.

The sun had dropped behind the far corner of Gebel Abu Fedah, and

with

the grateful shade the breeze had freshened and slightly cooled the

tepid atmosphere.

Wrapping his burnous around his tall figure, Kāra made dignified

obeisance.

“Osiris guard thee, my brother,” said he.

“May Horus grant thee peace,” answered Winston, humoring this

disciple

of the most ancient religion. Then he watched the Egyptian stalk

proudly

away over the hot sands, his figure erect, his step slow and

methodical,

his bearing absurdly dignified when contrasted with his dirty tunic

and

unwashed skin.

“I am in luck,” he thought, turning toward the bank to summon

Hassan and

Abdallah; “for I have aroused the rascal’s cupidity, and he will

soon

turn up something or other, I’ll be bound. Ugh! the dirty beast.”

At the foot of the mountains Kāra paused abruptly and stood

motionless,

staring moodily at the sands before him.

“It was worth the bother to get the cigarettes,” he muttered. Then

he

added, with sudden fierceness: “Twice he spurned me with his foot,

and

called me ‘dog’!”

And he spat in the sand and continued on his way.